Introduction

Two major developments in the political landscapes of western democracies in recent years have been the decline of working-class organisations, such as trade unions and social democratic parties, and the rise of populist radical right parties.Footnote 1 Although several explanations have been given for these trends, one of the foremost explanations has been structural economic change, including deindustrialisation and globalisation. This can be seen in the results of the recent Brexit referendum and United States (US) presidential election; the Leave campaign and Donald Trump won in large part thanks to their improvements in vote shares in areas that traditionally supported the Labour and Democratic parties. Many of these areas are in the English midlands and the American rust belt – areas that have been severely affected by the decline of manufacturing and industry.

With structural changes in the labour market, there has been growing concern about the division of labour markets in western democracies into labour market “outsiders”, those either in various forms of precarious employment (including temporary work, involuntary part-time work and low-wage work) or facing high future risk of precarious employment, and labour market insiders, those in secure, full-time jobs. While many of these labour market outsiders continue to support movements and parties on the left, recent research on support for populist radical right parties has shown that these parties do well among the unemployed (Arzheimer Reference Arzheimer2009) and those with low labour market status (Rovny and Rovny Reference Rueda2017). Populist radical right parties are anti-immigration, usually anti-globalisation and, unlike traditional right-wing parties that support free market economics, often favour protectionism and improving social programmes for natives. These appeals, regardless of whether or not they would actually improve outsiders’ material conditions, can be quite powerful because they convey the idea that populist radical right politicians, in contrast to the establishment parties, put the interests of common native people above those of nonnatives and elites.

What is less understood is how traditional working-class organisations may have lost their connection to the economically insecure. While part of this probably has to do with shifts to the left on immigration among both trade unions and social democratic parties, it may also have to do with increasing heterogeneity among their constituents. Recent work on the evolution of labour markets in western democracies has found that these organisations have become divided over promoting the interests of labour market insiders and labour market outsiders (Rueda Reference Rovny and Rovny2005). Social democratic parties and many trade unions have often, for example, prioritised employment protection for insiders over job creation for outsiders (Rueda Reference Rueda2007). Where trade unions and left-wing parties have prioritised insiders over outsiders, outsiders may be less willing to support them and more likely to support critical voice – that is the populist radical right.

However, this insider-outsider divide is not equally present in all western democracies. Labour market policies play an important role in this. Some countries, such as those in Scandinavia, have labour market policies that are designed to help reintegrate outsiders back into the regular labour force (Häusermann and Schwander Reference Häusermann, Kurer and Schwander2012). On the other hand, several continental European countries have high levels of employment protection for the currently employed, which may reduce outsiders’ likelihood of finding regular employment. In this article, I argue that these labour market policies should condition the effect of labour market status on political attitudes and can provide part of an explanation for why labour market outsiders may support the populist radical right over traditional left-wing organisations. Employment protection legislation (EPL) should increase the degree to which outsiders will favour the populist radical right over traditional left-wing organisations, whereas active labour market policy (ALMP) spending should have the opposite effect, reducing outsider support for the populist radical right with respect to the traditional left.

I test two primary hypotheses: (1) as EPL increases, outsiders will be less likely, relative to insiders, to support trade unions; and (2) as EPL increases, outsiders will be more likely, relative to insiders, to support a populist radical right party. Because I also argue that this will be offset somewhat by ALMP spending, I create a measure, labour market rigidity, which I define as the difference between a country’s level of EPL and ALMP. I show both that this measure has a similar effect on attitudes as employment protection and that when I include ALMP separately in regressions with EPL it has the opposite effect: it increases outsider support for unions, but decreases it for populist radical right parties. I find that a second type of labour market policy, passive labour market policy (PLMP), which consists of benefits targeted more at insiders, does not have the same offsetting effect on outsiders’ attitudes as ALMP, suggesting that the reintegrating effect of ALMP has an important effect on attitudes.

I define outsiders by two general criteria: (1) survey respondents’ employment status and (2) the employment status of others in their household. I code individuals as outsiders if they are unemployed or in part-time employment and, if they are not the head of the household, the head of the household is not in full-time employment. I find support for these hypotheses in combined European Values Survey – World Values Survey data on attitudes towards trade unions and populist radical right parties for 27 Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) countries for the period 1995–2009. These results are robust to a variety of model specifications, as well as different codings of populist radical right parties.

This article makes contributions to literature on labour market insecurity, the effects of labour market policies and support for populist radical right parties. In particular, it shows how the effects of labour market status on political attitudes are conditional on labour market policies and how these policies can affect the propensity of those in low status to favour the populist right over the traditional left. Indeed, while previous work on class voting suggests that the left may have lost voters to the populist right through its move to the centre on economic issues (Evans and Tilley Reference Evans and Tilley2012), this article suggests another possibility – that protection for insiders at the expense of outsiders may have contributed to this. Finally, while this article focusses on how labour market policies condition the effect of labour market status on political attitudes, the underlying mechanism that it proposes is more general. Industrial decline and the subsequent inability of many formerly middle-class workers to find good-paying jobs in many regions of the US and England, regardless of the reasons, can help explain support for nativist candidates and policies.

The insider-outsider divide and political realignment

There has been gradual political realignment across western democracies over recent decades. The social democratic left has become weaker, whereas new political movements on the left and right have become more popular. The German and Swedish social democratic parties, for example, lost roughly a quarter of their vote shares from the 1980s to the 2000s, declining from a decade average of 39.4% and 44.5% to 30.4% and 34.2%, respectively. New parties have gained prominence since the 1980s, most notably green parties and populist radical right parties. Trade unions, perhaps the most important mass organisations on the left, have declined to a similar extent. The average trade union density for 22 OECD countries has declined from 43.9% in the 1980s to 32.8% in the 2000s.Footnote 2

Although there are several possible explanations for these shifts in political support, among the most important are structural economic changes. The decline of heavy industry and manufacturing across the west has eroded the primary base of support for social democratic parties and trade unions. Technological change and trade have adversely affected employment opportunities for the less educated, with technological change causing an increase in high- and low-wage occupations relative to middle-wage occupations (Autor and Dorn Reference Autor and Dorn2013; Goos et al. Reference Goos, Manning and Salomons2014) and trade shocks causing lower lifetime earnings (Autor et al. Reference Autor, Dorn, Hansen and Song2014). Recent work has also shown that trade shocks have important implications for political behaviour. Regional shocks because of trade with China were associated with increased support for Brexit (Colantone and Stanig Reference Colantone and Stanig2018), increased nationalist attitudes and support for populist radical right parties across Europe (Colantone and Stanig Reference Colantone and StanigForthcoming) and increased political polarisation in the US (Autor et al. Reference Autor, Dorn, Hansen and Majlesin.d.).

What has been less appreciated in recent literature is the role that labour market policies play in conditioning how these changes translate into labour market outcomes. Recent work in comparative political economy has argued that a new labour market cleavage has developed in advanced postindustrial democracies: an insider-outsider divide between those with secure employment and those with insecure employment. The presence of this insider-outsider divide varies as a function of labour market policies. Rueda (Reference Rueda2014) argues that employment protection contributes to the maintenance of the insider-outsider divide and finds that where it is high, government spending on income support is less responsive to economic downturns. Häusermann and Schwander (Reference Häusermann, Kurer and Schwander2012) show that in continental and especially southern European countries, taxes and transfers disproportionally benefit insiders, enhancing the insider-outsider divide. However, social programmes help reduce market inequalities in Scandinavian countries, with a greater percentage of benefits helping reintegrate displaced workers.

Following this existing research, I argue that employment protection and social policy spending should affect the presence of an insider-outsider divide. EPL should increase the insider-outsider divide. It makes it more difficult to lay off employed workers, which can make employers more reluctant to hire new employees.Footnote 3 Although EPL increases the insider-outsider divide, social policy spending, in particular ALMP, can help reduce it.Footnote 4 ALMP consists of programmes such as assistance with job search and skill upgrading, which can both reduce the probability of long-term unemployment and help individuals at high risk of long-term unemployment develop new skills. It helps reintegrate outsiders into regular employment, reducing employment insecurity and its effects on attitudes.Footnote 5

There is a second type of policy, PLMP, which consists of unemployment benefits, disability benefits and early retirement benefits. These help individuals maintain their incomes when they lose their jobs, but do not help reintegrate the unemployed into the regular labour force. They are targeted more at insiders than outsiders. Because they do not help outsiders find regular employment, they do less to reduce the insider-outsider divide than ALMP and may not reduce the attitudinal effects of employment insecurity.

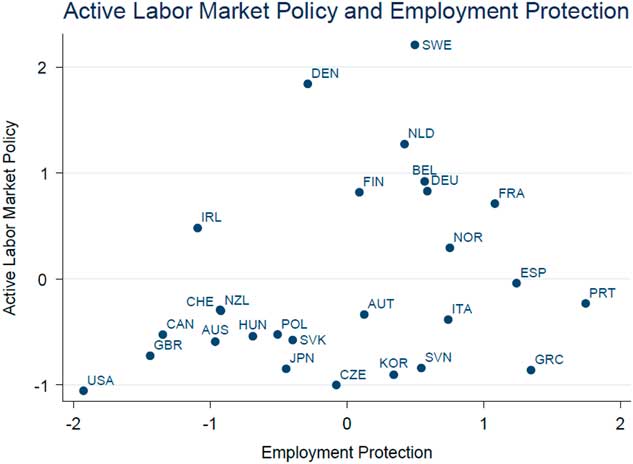

Figure 1 plots the average values for EPL and ALMP for 27 OECD countries for 1990–2010.Footnote 6 As we can see, ALMP spending is highest in the Scandinavian countries, whereas EPL is lowest in liberal market economies [the US, United Kingdom (UK) and Canada] and highest in southern European countries.

Figure 1 Active labour market policy and employment protection. Note: Employment protection legislation and active labour market policy are both standardised to have mean=0 and 1-unit SD. Country values are averages for 1990–2010. Source: OECD (Reference Oesch and Rennwald2014).

Labour market rigidity and political affinities

Much of the work on the insider-outsider divide posits that insiders and outsiders should have diverging welfare state policy interests and has focussed on developing schema for identifying insiders and outsiders, their policy preferences and their relationships with different political parties (Rueda Reference Rovny and Rovny2005; Schwander and Häusermann Reference Schwander and Häusermann2013). This research has, with some recent exceptions (Rovny and Rovny Reference Rueda2017), focussed less on how this might affect the balance of support among these individuals for traditional left-wing organisations versus the populist radical right. However, if social democratic parties and trade unions protect insiders at the expense of outsiders, we should expect that outsiders would be less likely to support them. We might also expect that they would feel greater affinity for the populist radical right. These parties criticise political and (to a lesser extent) economic elites, whom they accuse of being responsible for developments that, they argue, have hurt native workers, such as immigration and unfavourable trade policies. They often support employment and other social programmes, but only for natives.Footnote 7

I argue that labour market rigidity can mediate the effect of labour market status on support for the populist right over organisations associated with working-class insiders. To capture this, I examine attitudes towards trade unions and populist radical right parties.Footnote 8 When labour market rigidity is low, the insider-outsider divide should be weaker. Because it will be easier for outsiders to become reintegrated into regular employment, their prospects for future employment will be higher and the sense of insecurity owing to underemployment will be diminished. Insiders, however, will have a lower degree of job security and will be more concerned about the possibility that they could become outsiders in the future. However, where labour market rigidity is low and the insider-outsider divide is weaker, there is a natural coalition between outsiders and trade unions because these groups have similar interests in other areas of labour market and social policy.

Attitudes towards trade unions

Trade unions are perhaps the archetypical insider-oriented organisations, protecting and promoting the interests of members, even when this might harm employment prospects for nonmembers, many of whom may be in similar types of employment and otherwise sympathetic to unions and their political causes. Previous work on attitudes towards trade unions found that these tend to be most negative during periods of high unemployment and that high income and highly educated individuals are less likely to have positive attitudes towards unions (Turner and D’Art Reference Turner and D’Art2012).

Labour market rigidity should affect outsiders’ attitudes towards unions because outsiders stand to lose from the gains in protection. In a country with high labour market rigidity, trade unions and their members are in more of an insider position. Because unionised workers cannot be easily laid-off, unions face less pressure to accept wage concessions. When employment protection is high, there will be less wage restraint among unions, which will in turn lead to a reluctance to hire new workers and make it more difficult for outsiders to find regular employment. This may also lead to increased employer usage of temporary employment agencies, which hire workers for fixed-term contracts, typically at much lower wages and with fewer benefits than nonagency workers performing similar jobs. This may result in increased outsider resentment towards those, including trade unions, whom they see as relatively privileged by this situation.

The likely effects of labour market rigidity on insiders’ attitudes towards unions are more ambiguous. Although we might expect union members to approve of their unions more when rigidity is high because this allows them to bargain for higher wages, it is not clear that other insiders’ attitudes would be affected in the same way. On one hand, union bargained wages have positive spillover effects onto nonunionised workers (Rosenfeld Reference Rooduijn and Burgoon2014), which could result in more favourable views when rigidity is higher. On the other hand, when labour market regulations protect unions, they may be more likely to make excessive demands. Nonunion insiders may find this unreasonable. In any case, the likely effect of labour market rigidity on outsiders’ attitudes is clearer than it is for insiders’ attitudes.

Attitudes towards populist radical right parties

In contrast to the literature on attitudes towards trade unions, the literature on individual support for populist radical right parties is vast. Individual attitudes may be affected by both individual-level factors, such as employment insecurity or attitudes towards immigration, or contextual factors, such as the level of unemployment or immigration into the country.Footnote 9 Much of the discussion of individual-level demand-side factors has centred on employment, both on workers’ employment status and type of employment. One consistent finding is that members of the working class, particularly those in low-skills and manual labour jobs, are more likely to support populist radical right parties than other classes, except for small business owners/employees (Ivarsflaten Reference Ivarsflaten2005; Oesch and Rennwald Forthcoming). Another is that the unemployed and marginally employed are particularly likely to support populist radical right parties (Arzheimer Reference Arzheimer2009; Emmenegger et al. Reference Emmenegger, Marx and Schraff2015; Rovny and Rovny Reference Rueda2017).Footnote 10

Although there has been substantial focus on employment disadvantage, there has been less work on how support for populist radical right parties may be conditional on welfare state or labour market institutions. Swank and Betz (Reference Swank and Betz2003) found that where welfare state spending is higher, populist radical right parties are less successful. Arzheimer (Reference Arzheimer2009) found that the impact of welfare spending is conditional on the level of immigration, with a negative impact of the welfare state on populist radical right party support only at high levels of immigration. Neither of these studies examined how welfare state spending might condition the attitudes of specific subgroups.

When labour market rigidity is high, outsiders’ probability of entering regular employment will be lower, which may create backlash against both privileged groups and outgroups.Footnote 11 These are exactly the types of hostile reactions on which populist radical right parties base their appeals. They are at their core anti-elite, hostile to immigration and highly sensitive to perceived intrusions on national sovereignty (Mudde Reference Mudde2007). More generally, populist radical right politicians have explicitly linked anti-elitism, hostility to immigration and hostility to globalisation into something of a coherent narrative: political elites sell out natives both culturally and economically to immigrants; they sell out native workers to foreign workers and (in Europe) national sovereignty to the European Union. This narrative should appeal to natives with low-income status, who have borne the brunt of negative socioeconomic changes and would benefit from the elevation of their higher social status as natives (Shayo Reference Shayo2009), especially because these parties’ economic platforms often privilege natives. Recent work finds that vote shares for populist radical right parties are higher in regions that have been exposed to trade shocks with China and that individuals living in these regions were more likely support parties scoring highly on nationalist ideology generally (Colantone and Stanig Reference Colantone and StanigForthcoming).

At the same time, we would also expect labour market rigidity to affect insiders’ attitudes towards populist radical right parties. Where labour market rigidity is high, insiders’ jobs are protected from labour market competition. They should have a greater sense of job security, and therefore be less likely to support these parties. Thus, we could expect that the effect of an interaction between labour market rigidity and labour market status on support for populist radical right parties could be driven by its effect on both outsiders and insiders. When labour market rigidity is low, the difference between outsiders and insiders at the margin will be minimal. Despite having full-time, ostensibly permanent jobs, many insiders will face a high degree of insecurity because of the increased possibility of being laid off. Because of this, they may be more likely to support populist radical right parties than when their jobs are highly protected.

My study is most similar to those of Gingrich and Ansell (Reference Gingrich and Ansell2012) and Rooduijn and Burgoon (Reference RosenfeldForthcoming). Gingrich and Ansell find that the degree of employment regulation conditions the effect of personal economic risk on attitudes towards redistribution and the welfare state. Those who are employed in occupations with high unemployment (a proxy for employment risk) are less likely to support redistribution and welfare state programmes when there is high employment protection. Rooduijn and Burgoon find that those facing hardship are most likely to support populist radical right parties when general economic conditions are good. They argue that this supports a “relative deprivation” interpretation of individual support for right-wing populism on economic grounds – that it is not individual economic hardship per se that causes individual support for right-wing populism, but only individual economic hardship when things are generally going well for others. My results could be interpreted in this light: those with low employment status will be more likely to support the populist radical right when labour market rigidity is high and the difference in employment opportunities between them and insiders is greater.

Data and codings

I test my theory using data for 27 OECD countries from the combined European and World Values Surveys (EVS/WVS), administered, respectively, in 1981, 1990, 1999 and 2008, and 1990, 1995, 2000, 2005 and 2008 (European Values Survey 2011; World Values Survey 2014).Footnote 12 I chose the EVS/WVS rather than European Social Survey because the EVS/WVS has questions on union and party attitudes across multiple waves, whereas the European Social Survey only asks a question on union attitudes in its 2002 wave. Unfortunately, each country did not participate in every survey wave and the number of available surveys differs per country, ranging from two for Greece to seven for Spain.Footnote 13 As both sets of surveys contain the same key demographic variables and survey question wordings, I merged them into a single data file in order to maximise country-year observations.

Each wave of both the European and World Values Surveys asks the questions “How much confidence do you have in the following institutions: Trade Unions” (four categories) and “Which political party would you vote for: first choice”. These serve as my dependent variables. I use two separate codings for populist radical right parties, a party manifestos-based coding and an expert list-based coding. Although there is a core of parties currently in western Europe that scholars generally agree can be considered populist radical right, it is both less clear for earlier decades as to which parties should be included and less clear outside of western Europe as to which parties should be included. A manifestos-based coding has two advantages: (1) it can pick up parties that are populist radical right, but are in countries or years that have received less attention from scholars; and (2) it can pick up mainstream parties that have shifted to the right owing to a shift in issue saliency or electoral threat from populist radical right parties.Footnote 14

To generate the issue-based coding for populist right issues, I merged data from the Comparative Manifestos Project on party manifesto positions across democracies (Volkens et al. Reference Volkens, Lehmann, Merz, Regel and Werner2013) into the combined EVS/WVS and created an index for each party’s degree of social conservatism following the recommended coding and logit rescaling scheme in Lowe et al. (Reference Lowe, Benoit, Mikhaylov and Laver2011). I code parties in the top 10% of scores on this social conservatism scale as being populist radical right parties because where these parties have been present they have tended to receive between 5 and 15% of the vote between the 1980s and 2000s (Mudde Reference Mudde2013). For the expert-list-based coding, I rely primarily on the populist radical right party lists in Halikiopoulou and Vlandas (Reference Halikiopoulou and Vlandas2016) and Immerzeel et al. (Reference Immerzeel, Lubbers and Coffe2016). See Online Appendix A for further details on both coding schemes.

A measure of outsiders would ideally include employment status (part-time, temporary status and so on), wages, benefits, job security and future prospect of career advancement. There are two general types of existing outsider codings: (1) those based on occupational status, which code the unemployed, those in temporary employment and those in involuntary part-time employment as outsiders (Rueda Reference Rovny and Rovny2005; Emmenegger et al. Reference Emmenegger, Marx and Schraff2015); and (2) those based on the probability of future job loss (Rehm Reference Rehm2009; Häusermann et al. Reference Häusermann and Schwander2016). These take occupational unemployment as a proxy for employment risk, with individuals in higher unemployment occupations at higher risk. Häusermann et al. (Reference Häusermann and Schwander2016) develop a particularly sophisticated version of this type of coding, breaking occupational groups down further by sex and age.

I use a coding based on two types of employment status: (1) the respondent’s employment status, and (2) the employment status of others in the household. Recent work has shown that conceptions of outsiders based on low employment status predict individual support for right-wing populists, whereas those based on future employment risk are at best weak predictors (Rovny and Rovny Reference Rueda2017). However, it is also important to consider the employment status of others in the household, as recent work has shown that when there are insiders in the household the effect of respondent employment status on party and policy preferences is weaker (Marx and Picot Reference Marx and Picot2013; Häusermann et al. Reference Häusermann and Schwander2016).

Each wave of the EVS and WVS contains a question asking the respondent if he or she is employed full-time, employed part-time, self-employed, retired, a student, a housewife or unemployed. The first three waves of the EVS and first four waves of the WVS also contain a question on whether the respondent is the chief wage earner and whether the chief wage earner is employed. The 2008/2009 waves of the EVS and WVS replace these questions with a question about the employment status of the respondent’s partner. I create a coding in which the individual is considered to be an outsider if he or she is employed less than full-time and no other individual in the household is employed full-time. I drop individuals who we can reasonably expect not to be searching for employment, such as retired persons who are the chief household wage earner.Footnote 15 This is a relatively conservative measure because full-time employed individuals may also face a high risk of unemployment. It would also be sensible to include those who are employed full-time, but temporarily as outsiders. Unfortunately, there is no information in the EVS/WVS about whether the respondent is temporarily employed. There is also no way to determine whether the respondent is voluntarily or involuntarily part-time employed/unemployed.

Institutional data, including data on EPL, ALMP, and PLMP, as well as additional national-level data on immigration inflows, unemployment, gross domestic product (GDP) and GDP growth, all come from the OECD’s Stat Extracts (OECD 2014).Footnote 16 The original EPL measure consists of a 0–6 scale based upon 21 subindicators, with 6 indicating the highest level of protection while the original ALMP and PLMP measures are spending on these programmes as a percentage of GDP. I standardise all of these variables to have a mean of 0 and 1-unit SD. To account for the offsetting effect of ALMP on EPL, I also generate a labour market rigidity index (LMRI) based on the differences of the standardised values:

EPL and LMRI should both be associated with higher (lower) levels of outsider support for trade unions (populist radical right parties).

H1: As EPL/LMRI increase, outsiders will be less likely relative to insiders to support trade unions.

H2: As EPL/LMRI increases, outsiders will be more likely relative to insiders to support a populist radical right party.

Methods and results

The resulting data set has a hierarchical structure, with individuals nested in one of 27 countries for one of eight-year waves. Typical approaches when using data with individuals nested within countries are to both cluster standard errors by country and use fixed effects or to use multi-level models, specifying the nested structure of the data (individuals within countries, individuals within countries within years and so on). My main specifications all use country and year fixed effects, although I include robustness checks with multi-level models in the Online Appendix Table B.3. Although many differences between countries can be captured with country-level variables, it is likely that there are unobservables (such as aspects of national culture) that are relatively fixed and affect individuals’ propensities to have different employment statuses, as well as political attitudes generally. Any bias due to unobserved country-specific effects is especially problematic given the unequal number of surveys for each country. For attitudes towards unions, a four-category variable, I estimate my models using ordered logit. For populist radical right party support, I estimate my models using logit.

Table 1 presents regression results for attitudes towards unions and populist radical right parties.Footnote 17 The dependent variable in columns 1–3 is attitudes towards unions. The dependent variable in columns 4–6 is support for populist radical right parties with the manifestos-based coding. The dependent variable in columns 7–9 is support for populist radical right parties with the list-based coding. I include three types of regressions: (1) regressions with Outsider X EPL for each of the dependent variables in models 1, 4 and 7; (2) regressions with Outsider X LMRI and Outsider X PLMP in models 2, 5 and 8; and (3) models with country and year fixed effects where I separately interact outsider with EPL, ALMP and PLMP (models 3, 6 and 9). In these models, higher EPL should be associated with lower (higher) outsider support for trade unions (populist radical right parties) and higher ALMP should be associated with higher (lower) support for trade unions (populist radical right parties).

Table 1 Labour market rigidity, labour market status and attitudes towards unions and populist radical right parties

Note: Union regressions include individual-level controls for political ideology, union membership, age, sex, income and education; at the country-year level, they contain LMRI (model 2), employment protection legislation (EPL) (models 1 and 3), active labour market policy (ALMP) (model 3), passive labour market policy (PLMP) (model 3), the gini coefficient, logGDP, gross domestic product (GDP) growth, the unemployment rate and union density. Party regressions include individual-level controls for political ideology, union membership, age, sex, income, education and attitudes towards immigrants; at the country-year level, they contain LMRI (models 5 and 8), EPL (models 4,6,7,9), ALMP (models 6 and 9), PLMP (models 6 and 9), the gini coefficient, logGDP, GDP growth, the unemployment rate, the inward immigration rate and the effective number of political parties.

Standard errors clustered by country-year. Countries in all regressions are Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Czechia, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Japan, South Korea, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom and United States. Various years for each country 1995–2009.

*p<0.1, **p<0.05, ***p<0.01.

Looking at the results for attitudes towards unions in columns (1) and (2), we can see that outsiders are more likely (relative to insiders) to disapprove of unions when employment protection and labour market rigidity, respectively, are high, consistent with Hypothesis 1. In column (3), where I separately interact outsider with EPL and ALMP, the results are also consistent with expectations; outsiders are more likely to have negative attitudes towards unions when EPL is high, but less likely to have negative attitudes when ALMP is high. This also corroborates the idea behind LMRI – that EPL increases rigidity, but ALMP helps to reduce it. We can also see that in both models 2 and 3 Outsider X PLMP has the opposite sign as Outsider X ALMP, suggesting that PLMP does not have the same compensating effect on attitudes as ALMP.

The results for right-wing populist parties are also largely consistent with Hypothesis 2.Footnote 18 Both Outsider X EPL and Outsider X LMRI have a positive sign and are significant at p<0.05 for both dependent variables. As with attitudes towards unions, I interact outsider with EPL and ALMP separately in columns 6 and 9. Although the results for the manifestos-based coding of parties show that EPL and ALMP have the expected opposite effect on outsiders’ attitudes towards right-wing populist parties, I only find the expected effect for EPL in the list-based coding. The results for PLMP are interesting. In three of the four regressions, outsiders are more likely at higher levels of PLMP to support populist radical right parties. Another interesting result is that all else equal, outsiders are only more likely to support right-wing populist parties using the manifestos-based coding of parties. This suggests that, in addition to the finding of Rovny and Rovny (Reference Rueda2017) that differences across codings of outsiders matter for populist radical right party support, differences in how these parties are coded matter as well.

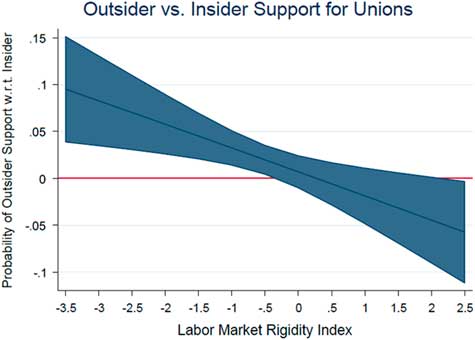

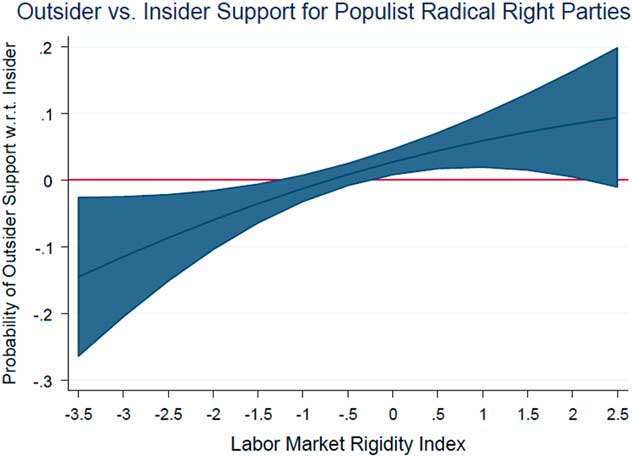

To better assess the effect of how being an outsider varies across values of labour market rigidity, I present graphs of the difference between outsider and insider support for unions and populist radical right parties across values of LMRI in Figures 2 and 3.Footnote 19 In Figure 2, we see that as LMRI increases, outsiders become less likely with respect to insiders to support trade unions. The change in the difference across values of labour market rigidity is fairly large – about 15 percentage points from the lowest to highest values. At the lowest levels of labour market rigidity, between −3 and −3.5 (roughly the levels in Sweden in 1996 and Denmark in 1999), outsiders are about 8–10% more likely than insiders to support trade unions. Between 1.5 and 2, roughly the levels for Spain in 1995 and Greece in 2008, outsiders are about 3–5% less likely to support trade unions. This shows a further interesting result: that at low levels of labour market rigidity outsiders are more likely than insiders to support trade unions, whereas at high levels of labour market rigidity outsiders are less likely to support trade unions. This result is even stronger than the theoretical prediction, which was just that outsiders would become less likely relative to insiders to support trade unions as labour market rigidity increases. It suggests that when labour market rigidity is low, outsiders perceive unions as less protective of insider interests, insiders perceive unions as less protective of their own interests or both.

Figure 2 Outsider versus insider attitudes towards trade unions across values of labour market rigidity. Note: Graph based on dichotomised dependent variable version of Table 1, column 1. X-axis covers the actual range of variable values in the data.

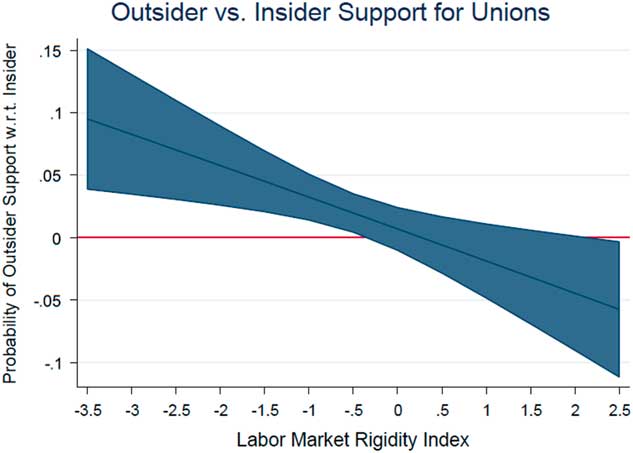

Figure 3 Outsider versus insider attitudes towards populist radical right parties across values of labour market rigidity. Note: Graph based on manifestos-based coding in Table 1, column 4. X-axis covers the actual range of variable values in the data.

Figure 3 shows the probability of outsider, relative to insider, support for a populist radical right party across levels of LMRI, based on model 5. The likelihood that outsiders will support populist radical right parties increases with labour market rigidity, with outsiders being less likely than insiders to support a populist radical right party at low levels of labour market rigidity. The change in the differential across values of labour market rigidity is substantial – about 25 percentage points from the lowest to highest values, although the confidence intervals at the highest and lowest levels are wider than for unions. At the lowest levels, outsiders are approximately 10–15% less likely to support populist radical right parties than insiders. At middle and high levels, outsiders are approximately 7–9% more likely to support populist radical right parties. With labour market rigidity of between 0.5 and 1, which include the levels in France in 2006 and 2008 and Italy in 1999, outsiders are a precisely estimated 4–6% more likely than insiders to support populist radical right parties. As with unions, this result also goes beyond my hypothesis, which was that outsiders would just become more likely relative to insiders to support populist radical right parties as labour market rigidity increases. It is surprising given existing work showing that various types of labour market outsiders are more likely than others to support populist radical right parties. My results show that this is strongly conditional on the degree of labour market rigidity. At the mean level and high levels of labour market rigidity in this model, outsiders are more likely than insiders to support populist right parties. However, at low levels, outsiders are less likely to support radical right populist parties.

I include additional analyses in the Online Appendix. In Table B.2, I rerun the main specification with three different codings of outsider: (1) dropping the conditions about the employment status of others in the household; (2) counting just unemployed individuals as outsiders; and (3) counting just part-time workers as outsiders. The results are robust to the first recoding, but while the signs are the same most of the results are not significant for the latter two. Although it is difficult to say conclusively, this could be because of the much smaller samples of outsiders – the coefficient magnitudes in columns 4–9 are similar to those in columns 1–3. In Table B.3, I run the main specification for each variable with fixed effects ordinary least squares rather than fixed effects ordered logit or logit. The results are slightly weaker for the list-based coding of parties, but are overall similar. Finally, I run a series of jackknife tests, where I rerun the main specification dropping each country and year individually. The results are substantively similar with a few exceptions: the union results are sensitive to dropping Sweden (Outsider X LMRI: p≈0.16) and both the union and list coding of parties results are sensitive to dropping the year 1999 (Outsider X LMRI: p≈0.12 and p≈0.14, respectively). Sweden and the 1999 wave of the ESS have the largest number of observations for countries and waves, respectively, so it is difficult to interpret whether these variations are due to inconsistency with the theory or loss of sample size. In any case, 97% (107 of 110) of the jackknife regressions produced the same substantive results as those reported here.

Conclusion

In this article, I have shown that as labour market rigidity increases, labour market outsiders become less likely relative to insiders to support trade unions and more likely to support populist radical right political parties. This provides one explanation for why those in disadvantaged labour market positions may shift their support from traditional organisations of the working class left to the populist radical right. I do not claim, however, that this is a comprehensive explanation for the growth of populist radical right parties relative to social democratic parties. Recently, support for populist radical right parties across Europe has increased in response to the increased flow of refugees and migrants from outside of Europe. One area for future research is to determine whether the effect of inward migration on support for populist radical right parties is heterogeneous across labour market status and labour market policy regimes.

My findings have important implications for understanding the effects of labour market policies and, because of this, for how we think about the tradeoffs between different types of policies. While employment protections increase security among insiders, they can have the opposite effects on outsiders. This can affect political cohesion between these groups. Although working-class insiders may agree on many matters of social policy, such as taxation or unemployment benefits, employment protections may drive a wedge between these groups and reduce solidarity, which might otherwise exist.

My results suggest that this is also the case for social policy spending. Among the most interesting findings are the contrasting results for ALMP and PLMP. Although ALMP appears to offset some of the divisive effects of EPL, this is not the case for PLMP. PLMP does not affect outsiders’ attitudes towards unions and is often associated with increased outsider support for populist radical right parties. Why might this be? One possibility is that, although outsiders receive some benefits of PLMP, these policies do not help reintegrate them into the labour market and that it is labour market integration that reduces populist radical right support. ALMPs promote social inclusion, which in turn weakens individual preferences for extreme politics, whereas PLMPs only reduce life risk, doing less to help reintegrate individuals into the regular workforce and potentially fostering social alienation.

If we believe that the growth of support for populist radical right parties is problematic and is due at least in part to increasing economic insecurity, this suggests that we may be able to reduce this support through targeted programmes to promote job creation among labour market outsiders. My results also suggest that other PLMPs, such as a basic minimum income or disability benefits, may not solve some of these problems. Although it would be premature to conclude anything about the likely effect of a basic minimum income from these results, effects on political attitudes have been at most a minor part of discussions of basic minimum income. We should make these a more important part of the discussion. Spending on disability benefits, pensions for individuals who are unable to work, has continued to grow in many western democracies (Burkhauser et al. Reference Burkhauser, Daly, McVicar and Wilkins2014). The highest rates of Social Security Disability Insurance and Supplemental Security Income Spending in the US in 2013 were West Virginia, Kentucky, Alabama, Mississippi and Arkansas – all states that voted heavily for Trump (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities 2017). Although we cannot draw conclusions from this about the effect of these benefits on individuals’ political attitudes, they suggest that a high level of disability spending is at least consistent with support for populist radical right politicians. Future research should try to establish whether receipt of disability benefits affects individuals’ political attitudes.

Finally, my results also suggest that the populist radical right coalition may differ across countries. Populist radical right parties have done very well in countries with low labour market rigidity, like Sweden, so labour market rigidity does not appear to decrease their overall chance of success. It may be that economically secure workers are more likely to support these parties in countries where labour market rigidity is low. Variations on this theory could also be tested using subnational data. The theory would have to be made more general as there typically is no variation in these labour market policies within country. However, the theory is easily generalisable beyond these two types of policies or even labour market rigidity; there may be other factors such as local unemployment or immigration inflows that make it more difficult for natives to find employment and make them more likely to support populist radical right parties.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X18000211

Data. Replication files are available on the author’s Dataverse page at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/TLNMPB

Acknowledgement

The author thank Alexandra Cirone, Marco Giani, Anke Hassel, John Huber, Marcartan Humphreys, Isabela Mares, Vicky Murillo, Pierce O’Reilly and Josh Whitford, as well as participants of the 2013 EPSA annual meetings and seminar participants at the Hertie School of Governance, the University of Reading and the London School of Economics for helpful comments.