Public agencies are the policy handmaidens of legislatures. Or are they? In the United States (US), federal agencies routinely issue legally binding government regulations (also called “rules”) that provide the detail necessary to implement, enforce and enable the laws passed by Congress and signed by the president. Such regulations are critical governance tools; in fact, “[i]t is to rules, not to statutes or other containers of the law, that we turn most often for an understanding of what is expected of us and what we can expect from government” (Kerwin and Furlong Reference Kerwin and Furlong2018). Yet, a strong case can be made that puts legislatures in the driver’s seat of the agency policymaking process (McCubbins Reference McCubbins1985; Bawn Reference Bawn1997; Huber et al. Reference Huber, Shipan and Pfahler2001; West and Raso Reference West and Raso2013). In particular, Congress controls the delegation of rulemaking authority to federal agencies, and agencies are prohibited from writing rules unless they have legislative permission to do so (West Reference West1995; Haeder and Yackee Reference Haeder and Yackee2015; Rosenbloom Reference Rosenbloom2018).

While this summation – which suggests the primacy of Congress – may be technically accurate, it also provides an incomplete picture. In particular, it ignores the fact that agencies generally control the timing of agency action, which is, in and of itself, a political decision (Carpenter Reference Carpenter2002; Carpenter et al. Reference Carpenter, Chattopadhyay, Moffitt and Nall2012; Callander and Krehbiel Reference Callander and Krehbiel2014; Potter Reference Potter2019; Haeder and Yackee Reference Haeder and Yackee2020a, Reference Haeder and Yackee2020b). In this article, we demonstrate that agencies routinely take years, even decades, to issue regulations in response to statutory delegations of rulemaking authority. This raises a number of questions, including how much democratic control does legislation – and hence Congress – really hold over agency rulemaking? And, under what conditions are agencies more (or less) responsive to congressional demand for regulation? We provide new answers to these old questions by focusing on the passage of time between: (1) a congressional statute delegating new rulemaking authority to an agency and (2) the agency’s first draft rule using that delegated authority. In doing so, we assess empirically the political, agency and environmental factors that speed up or slow down the government’s regulatory responsiveness in the US.

We theorise that the breadth of the congressional statutory delegation of regulatory authority is a key factor driving regulatory timing. Specifically, when Congress expressly directs an agency to promulgate a rule, we hypothesise that agencies issue those rules more quickly. We refer to this as a narrow delegation. Narrow delegations command, often stating that an agency “shall” or “must” issue a rule. We argue that the amount of elapsed time between Congress’ demand for a regulation and an agency’s promulgation of a regulation will be shorter when Congress provides a narrow delegation. Yet, perhaps the more interesting state of affairs occurs in the opposite scenario, when the statutory authorisation provides a broad delegation of policymaking authority to the bureaucracy. Broad delegations suggest that an agency “may” write a regulation – meaning that Congress allows the agency and autonomy to decide whether or not to write a rule at all. Understood in this way, broad delegations provide decision-making autonomy to agencies. In these cases, we hypothesise that the bureaucracy’s internal considerations will be the key drivers of rule timing as opposed to other ex ante, ex post and contemporaneous political factors, which are frequently emphasised in the political science literature.

We use a large dataset that spans four decades to assess our argument, which links the legislature’s demand for regulation to the bureaucracy’s supply of regulation. In doing so, we provide the first quantitative examination of the timing of agency regulations in response to varying congressional delegations of regulatory authority. We analyse 348 laws delegating rulemaking authority to the US Department of the Interior (DOI) over an almost forty-year time period. These laws are then matched to all draft rules issued by DOI agencies over roughly the same period. We focus on DOI for several reasons, including that Interior’s rule-writing agencies hold jurisdiction over an unusually diverse array of critical policy areas (Utley and Mackintosh Reference Utley and Mackintosh1989). We employ flexible parametric models to understand the factors that speed or slow down agency responsiveness to congressional delegations of authority. These techniques, which are innovative in the field (Haeder Reference Haeder2019), allow us to determine the statistical and substantive significance of our theorised drivers across time, while also producing figures that jointly vary predictor variables to better understand how “real world” scenarios affect regulatory timing.

Overall, we find support for our argument: the breadth of the congressional authorising delegation is strongly associated with agency policy responsiveness, which we conceptualise via regulatory timing. When a statute directs DOI to write a draft rule, the agency generally does so and does so quickly – almost 50% of such statutes produce a rule within a one-year time period. Moreover, other political factors are also important to rule timing under these narrow delegations, including prestatute congressional hearings. However, for broad delegations of authority, which provide greater discretion to agencies, different patterns emerge. To begin, we find that broad delegations significantly outnumber narrow delegations, and many broad delegations go unanswered, which suggests that the agency may never issue a legally binding rule. Furthermore, when a draft rule is issued, DOI typically takes a long time to do so: two years after the authorisation, less than 20% of statutes with broad delegations produce a draft agency rule. Our analysis also suggests that under broad delegations, when rules are triggered, they are affected by DOI agency-related considerations, such as resources and workload, as well as statutory deadlines, but not by the factors that tend to dominate scholarship, such as the partisan configuration of government (i.e. a unified or divided government).

This article’s theory and findings hold important implications for politics and policy. We know now that the breadth of the original legislative delegation matters to the timing of agency policymaking, and we know that clear congressional demands for regulation are generally met with a quick agency response. In this sense, legislation appears to have a strong hold over regulation. Some observers may find these results reassuring and suggestive of the power that our elected policymakers have over (generally) unelected bureaucrats. However, we also know now that most congressional delegations are of the “broad” variety. And once this type of authority has been transferred, an agency often takes years to issue a draft rule; the timing of which appears often in reaction to its – i.e. the agency’s – own considerations. Some observers may see such findings as a distress call in need of a solution, such as legislative sunset provisions attached to all statutory authorisations of rulemaking. For instance, Adler and Walker (Reference Adler and Walker2020) see such delegations as normatively troubling – so troubling that they recommend that Congress ought to act to “mitigate the democratic deficits that accompany broad delegations of lawmaking authority to federal agencies and spur more regulatory legislative engagement with federal regulatory policy.” However, others may view our article’s results as benign, and perhaps indicative of the policymaking flexibility that agency officials need – and Congress willingly provides – to allow the bureaucracy to achieve its mission. Yet, regardless of what one sees, this article adds new evidence to the debate by extending scholarly and practitioner knowledge around one of the premier normative issues in political science: the fraught relationship between legislative delegation and agency policymaking discretion (Lavertu and Weimer Reference Lavertu and Weimer2009).

Theoretical foundations

At first blush, the demand and supply of agency regulation is hard to reconcile with the US Constitution, which states that Congress must make the laws (USA. Const. 1, 1). This reconciliation is made possible in large part by the fact that agencies cannot issue legally binding regulations without an explicit authorisation to do so in enacted law (Posner and Vermeule Reference Posner and Vermeule2002; Rosenbloom Reference Rosenbloom2018; Adler and Walker Reference Adler and Walker2020). Thus, there must be a statutory basis for agency policymaking. In providing this, Congress can transmit autonomy to government agencies to take advantage of agency expertise and to address issues of policy complexity (Epstein and O’Halloran Reference Epstein and O’Halloran1999; McCubbins Reference McCubbins1999; Huber and McCarty Reference Huber and McCarty2004; Kaufman Reference Kaufman2001; Boushey and McGrath Reference Boushey and McGrath2017). Or, perhaps, as Rourke (Reference Rourke1984) concludes, to “shift the burden of finding solutions to administrators, by granting them broad discretionary authority.”

Congressional control

One of the principal concerns for American lawmaking today is that delegation “creates problems for the US Congress when it comes to maintaining control over public policy” (MacDonald Reference MacDonald2010). This occurs in part because when Congress devolves authority, it allows the agency to make the first policy move, which if not preempted, generally wins out (Ferejohn and Shipan Reference Ferejohn and Shipan1990). As a result, when Congress uses its legislative policymaking power to enable administrative policymaking, there is a risk that agenda setting turns into agenda shifting (Maynard-Moody Reference Maynard-Moody1998). Or, as Weingast (Reference Weingast, Aberbach and Peterson2005) puts it, congressional delegation always creates the risk that agency policy outputs will not be responsive to the interests of elected officials and their constituents – a risk that is present even when agency officials earnestly pursue congressional intent (McCubbins Reference McCubbins1985). Consequently, understanding agency responsiveness (or lack thereof) after legislative delegation is critical because the “normative debates about the desirability and legitimacy of delegation hinge on the positive question of whether and how Congress can control the decisions of agencies” (Bawn Reference Bawn1997).

The tactics used by Congress to retain political control over delegated policymaking authority are many. The literature, for instance, suggests that Congress utilises agency budgets, political appointments and oversight hearings to influence the US bureaucracy (McCubbins and Schwartz Reference McCubbins and Schwartz1984; Wood and Waterman Reference Wood and Waterman1991; West Reference West1995; Aberbach Reference Aberbach2001; Lewis Reference Lewis2011), and often employs a principal-agent framework to understand the Congress-bureaucracy relationship (Miller Reference Miller2005; Wood and Waterman Reference Wood and Waterman1991). In this article, we focus attention on Congress’ use of statutes – and specifically the text of legislative statutes that have been signed into law by the president – to achieve bureaucratic responsiveness. In doing so, we follow Huber et al. (Reference Huber, Shipan and Pfahler2001), who define statutory control as when “legislators use legislation to influence agency decisions.”

Statutory control is an attractive congressional influence tactic for a number of reasons. First, statutes both constrain and enable agency policymaking action. Stated differently, they outline what public agencies can and cannot do. Huber and Shipan (Reference Huber and Shipan2002), for instance, make the case that when legislators pass more detailed statutes, they are attempting to limit the discretion of agencies. Indeed, it is frequently acknowledged that statutes are used to restrict and to structure how an agency will make policy choices – often through the use of administrative procedures (McCubbins Reference McCubbins1985; McCubbins et al. Reference McCubbins, Noll and Weingast1987, Reference McCubbins, Noll and Weingast1989; Epstein and O’Halloran Reference Epstein and O’Halloran1999; Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis2002; Moffitt Reference Moffitt2014). Yet, statutes are a dual-edged sword as they do not just constrain and limit behaviour, they also enable agency policymaking in the first place, and therefore they provide agencies the necessary legitimation and autonomy to issue policy decisions (Hill and Lynn Jr Reference Hill and Lynn2015).

Second, statutes are legally binding, and thus agencies must largely follow the dictates of statutes. After all, ignoring a congressional statutory command differs from, for example, ignoring the commands of a member of Congress made during a committee hearing, in a press release, or in a letter to an agency. While such actions may threaten, statutes hold the force of law and may be litigated. As a result, “when faced with lawsuits for failing to perform nondiscretionary duties, agencies tend to settle because their liability is clear” (Johnson Reference Johnson2013).

Third, statutes are durable (Shepsle Reference Shepsle1992). The coalitional politics necessary to pass a statute, which is signed into law by the president, ensure most statutes’ permanency. In other words, statutes regularly remain in effect for a long period of time and are difficult to reverse or revise. Indeed, given that other oversight activities are often “conditional on the ability of lawmakers to enact new laws” (MacDonald Reference MacDonald2010; see also Shipan Reference Shipan2004), the durability of statutes arguably elevates statutory control over other types of congressional control tactics.

The timing of agency action

What is a legislature “controlling” when it uses a statute to affect agency decision making? Within the context of a statutory delegation of policymaking authority, Congress is setting the agency’s agenda, suggesting what can, and at times what should, be the agency’s policy priorities and actions (West and Raso Reference West and Raso2013; Kerwin and Furlong Reference Kerwin and Furlong2018). This agenda setting role raises a number of questions, of which we are particularly interested in when agencies respond to legislative agenda setting, as well as why. Thus, our focus acknowledges that agencies make policy choices when they make timing choices, such as the decision to speed up or slow down agency action (Ando Reference Ando1999; Carpenter Reference Carpenter2002, Reference Carpenter2004; Potter Reference Potter2019). It also acknowledges that the timing of agency regulations, in particular, is an important political act (Revesz and Davis Noll Reference Revesz and Davis Noll2019). In the end, “agencies have significant time discretion in their operations and decisions”; yet, surprisingly, this type of timing discretion has not been “heavily studied” by scholars, researchers or practitioners (Carpenter et al. Reference Carpenter, Chattopadhyay, Moffitt and Nall2012).

Most observers suggest that if a shorter duration of time elapses between the Congress’ demand for agency action and the agency’s supply of that action, then this is indicative of greater agency responsiveness (Lowande Reference Lowande2019). And, while shorter may not always be better, reasonable people will likely agree that, when Congress tells an agency to issue a draft rule and it takes several decades for the agency to do so, it does not indicate particularly responsive behaviour. This general assumption is also well reflected in the literature, which, when it has focused on regulatory timing, has tended to emphasise the ability of legislatures to insert deadlines into some statutes to speed up the responsiveness of agency policymaking (Carpenter Reference Carpenter2004; Lavertu and Yackee Reference Lavertu and Yackee2012; Carpenter et al. Reference Carpenter, Chattopadhyay, Moffitt and Nall2012). As a result, while the exact normative threshold for what constitutes “responsiveness” may be difficult to pin down, it is clear that, at a minimum, the idea of responsiveness has elements of timing built in.

Bertelli and Doherty (Reference Bertelli and Doherty2019) offer an important innovation by focusing on calendar and political time. In their analysis of congressionally imposed deadlines, they find that while federal government agencies frequently miss rule-specific date deadlines in congressional statutes, agencies often promulgate these same rules before the next major political election. This critical finding helps to reorient the literature by emphasising the need to consider political time as part of an agency’s calculus on rule promulgation. Time is also built into what Freeman and Spence (Reference Freeman and Spence2014) call the problem of the Two Congresses. This refers to the fact that the Congress that originally enacts a statute delegating policymaking authority to an agency is generally not the same – in terms of its make-up or preferences – as the Congress in office when an agency ultimately issues a draft regulation using its delegated rulemaking authority. As Yaver (Reference Yaver2015) explains, “[M]any significant laws being implemented today were passed several Congresses ago, [and] the policy preferences of these Congresses may be highly divergent, leading to potentially substantial coalition drift.” This problem is created in part by the fact that the Administrative Procedure Act of 1946, which requires agencies to take public feedback on draft regulations before issuing legally binding rules, automatically builds some delay into the agency policymaking process (West Reference West1995; Rosenbloom Reference Rosenbloom2018). Nevertheless, when time elapses between a congressional delegation and the agency’s use of this delegated authority to make policy, it creates a time consistency problem that holds implications for our understanding of bureaucratic responsiveness to Congress (Shepsle Reference Shepsle1992). Or, as Adler and Walker (Reference Adler and Walker2020) put it, “In this respect, the lag between delegation and regulation may create a particularly concerning democratic deficit.” When taken together, this suggests a need to unpack and to measure the dynamic nature of agency responsiveness to congressional calls for agency regulation.

Argument

We seek to understand when legislation triggers regulation, and in so doing, to better explicate the link between delegation and discretion as it unfolds over time. To accomplish this, we drill down on the relationship between legislative statutes that delegate new rulemaking authority to public agencies and the timing of agency regulations that employ this delegated discretion. While the delegation literature is vast, we throw new light on what West and Raso (Reference West and Raso2013) write “has received little attention” from scholars to the point that it has been “almost completely ignored”: the role of Congress in directing future agency policymaking.

We begin with the uncontroversial claim that not all instances of delegation passed by legislatures are the same. In making this distinction, we suggest the importance of what Crawford and Ostrom (Reference Crawford and Ostrom1995) label the “grammar” of political institutions. We theorise that the grammar, if you will, used in the statutory delegation of rulemaking authority is critical to our understanding of agency responsiveness because it – in just a word or two – succinctly sets up the rules of the game. In short, it establishes the broad parameters of what the agency can and cannot do. Of particular interest to us is the weight that Crawford and Ostrom (Reference Crawford and Ostrom1995) place on the modal operators used in grammar’s deontic logic – especially shall and must as compared to may. As Crawford and Ostrom (Reference Crawford and Ostrom1995) theorise, these operators are key to understanding the relationships set forth in political texts because these are the words that define what is obligatory and what is permitted and distinguish between what are “prescriptive and nonprescriptive statements.”

Congress habitually uses these deontic logic operators in its statutes to delegate regulatory authority to federal agencies (see e.g. Copeland Reference Copeland2010), and we theorise that these operators are pivotal to understanding when, as well as why, agencies issue regulations in response to new delegated authority. Specifically, we suggest a distinction between statutes that provide a narrow delegation of decision-making autonomy from those that provide a broad delegation. Importantly, we suggest that this statutory distinction – between narrow and broad delegation regimes – is a parsimonious way to understand the scope of the original legislative act, and we expect it to hold policy effects for the timing of agency regulations.

Narrow delegations, we argue, are those where Congress tells an agency that it shall or must issue a regulation in response to new statutory authority. We see these as “narrow” in the sense that the level of discretion provided to the agency is circumscribed: issuing a rule is nearly obligatory. Of course, as Crawford and Ostrom (Reference Crawford and Ostrom1995) highlight, this type of mandatory language begs the question, “or else?” In this case, the sanctions are relatively clear for agency noncompliance. That is, one can expect that if an agency fails to issue a regulation when commanded by statute to do so – or is particularly delayed in doing so – affected parties will sue the agency and force it to carry out its legal obligation (Johnson Reference Johnson2013). Or, as West and Raso (Reference West and Raso2013) put it, “The primary way in which courts can shape the bureaucracy’s policy-making agenda is by enforcing statutes that require agencies to issue rules.” Moreover, an agency can reliably believe that sanctions will be forthcoming from Congress, if not from the courts. After all, Congress presumably has an interest in assuring that government agencies follow its clear statutory commands and therefore has an increased likelihood of using tools to punish agencies for noncompliance, such as budgets, hearings and appointments.

Broad delegations are those where Congress tells an agency that it “may” issue a regulation in response to a new grant of policymaking authority. Crawford and Ostrom (Reference Crawford and Ostrom1995) call this deontic logic operator “perplexing,” in the sense that it prescribes behaviour but does not specifically require it; that is, it permits action, while essentially suggesting that the agency may use its collective judgement as to if and when to pursue it. Walters (Reference Walters2019) also suggests that “may” grants of rulemaking authority are complicated because they provide little by way of concrete instruction from Congress. We see this form of statutory control – assuming “control” is the appropriate word – as providing a quintessential illustration of devolved discretion to agencies.

Hypothesis 1: Our key hypothesis that the amount of elapsed time between Congress’ demand for a regulation and an agency’s promulgation of that regulation will be shorter when Congress provides a narrow delegation than when it provides a broad delegation. As McCubbins (Reference McCubbins1999) writes, “Federal agencies are creatures of Congress and are subject to the strictures of their creator,” and we also know that the “force of new legislation makes it a powerful tool” (Weingast Reference Weingast, Aberbach and Peterson2005). Thus, when Congress passes an action-forcing statute, such as a statute with a narrow delegation, we argue that there will be a relatively quick regulatory response from the agency. In many ways, this pattern matches what scholars have long suspected, which is that the regulatory agenda is marked by punctuations of rules that closely follow new legislation, which calls for regulation action (Golden Reference Golden2003).

Hypothesis 2: We also hypothesize that when a narrow delegation is paired with other clear signals from Congress regarding its interest in a statute, it will work to further speed up agency action. We situate this hypothesis in the literature suggesting that agencies respond to signals sent by their political principals (Wood and Waterman Reference Wood and Waterman1991; Shipan Reference Shipan2004; Huber Reference Huber2007). We expect agency action to be more focused on regulations where there has been a clear expression of interest from Congress (Yackee and Yackee Reference Yackee and Yackee2010).

Hypothesis 3: Finally, we hypothesize that the bureaucracy’s internal considerations – such as its regulatory experience and contemporaneous resources – will be key drivers of rule timing when a statute provides a broad delegation of policymaking authority to the bureaucracy. After all, we know that, from Sunstein and Vermeule’s (Reference Sunstein and Vermeule2014) work, the number of rules most agencies could issue at any point in time is often high, and consequently, agencies must continually prioritise the promulgation of some agency rules and delay work on others. Thus, when provided the flexibility and autonomy of a “may” delegation of authority, we expect this type of prioritisation process will be affected in part by workload factors contemporaneously impacting an agency.

To be clear, we are not suggesting that Congress’ choice between narrow and broad delegation language is a procedural one; the literature is replete with examples of how procedural requirements may influence agency decisionmaking (e.g. McCubbins et al. Reference McCubbins, Noll and Weingast1987, Reference McCubbins, Noll and Weingast1989; Balla Reference Balla1998; Epstein and O’Halloran Reference Epstein and O’Halloran1999). Nor are we suggesting that this choice is akin to the overall level of detail provided in the statute (Huber and Shipan Reference Huber and Shipan2002). Instead, we are arguing that the narrow and broad delegation distinction is a fundamental, substantive and parsimonious statutory construction choice that is routinely and purposively used by Congress to affect agency behaviour. Given this, we are interested in the downstream policy consequences of this choice, as well as any commensurate implications for bureaucratic policy responsiveness.

Testing the argument

We assess the argument by focusing on the dynamic empirical relationship between the policymaking authority centred in the legislative branch and the policymaking actions of the executive branch. More specifically, we use a large dataset that spans four decades (Haeder and Yackee Reference Haeder and Yackee2021), which links the legislature’s demand for regulation to the bureaucracy’s supply of regulation. In doing so, we assess the article’s three hypotheses regarding agency policy responsiveness.

Data

Our analysis is based on information from two previously collected datasets, which we bring together and significantly expand upon to produce innovative, new research regarding the timing of draft agency rules. The main dataset focuses on all statutory grants of regulatory policymaking power to DOI from 1950 to 1987. The focus on DOI provides several benefits to our assessments. In particular, DOI and its many subagencies have a broad regulatory mandate – from mining rights to endangered species to tribal health care (Utley and Mackintosh Reference Utley and Mackintosh1989) – which assists in the generalisability of the results.Footnote 1 Moreover, this time period allows us to undertake an empirical examination of the modern administrative state immediately after the implementation of the pivotal Administrative Procedure Act of 1946 (APA) (Rosenbloom Reference Rosenbloom2000). The APA is a quasi-constitutional statute that, even today, sets the standards for all federal agency rulemaking and thus remains a fresh topic of continued scholarly debate (West Reference West1995; Kerwin and Furlong Reference Kerwin and Furlong2018; Rosenbloom Reference Rosenbloom2018).

Both datasets were originally compiled by Yackee and Yackee (Reference Yackee and Yackee2016). However, as we highlight below, we also supplement these datasets significantly with our own original data collection efforts. The first dataset contains information on all 348 statutes passed by Congress that directed new rulemaking authority to DOI from 1950 to 1987. Using a set of coding rules, they identified all rulemaking authority delegations to DOI and its agencies from the text of public laws. Regarding these statutes’ general distribution, they are distributed with consistency across time, and we do not see major changes across the period of observation. The second dataset is based on information collected on all Notice of Proposed Rulemakings (also called “NPRMs” or “draft rules”) issued by DOI from 1950 to 1990. They used trained coders to identify the relevant NPRMs in the Federal Register. These coders discerned the statutory authority citation(s) for the regulation, which allows for a matching of the 348 statutes in our study to the first NPRM issued by DOI that employs that statutory authority.

Variables

We create the article’s dependent variable of interest, Time to Draft Rule, which is a count of the number of days between a congressional statute delegating new rulemaking authority to DOI and the first draft rule issued by DOI using that delegated authority. We focus on the NPRM because it is the first major milestone indicating agency regulatory policy responsiveness. Our main explanatory variable, Narrow Delegation, is dichotomous and measures whether a delegation grant is narrow (coded as a 1) or broad (coded as a 0).Footnote 2 Narrow grants are those that instruct DOI that it “must” or “shall” issue a regulation. Broad grants are more ambiguous and often include the word “may” in the statutory delegation (Walters Reference Walters2019).Footnote 3 Overall, there are 69 narrow grants and 279 broad delegation grants in the data. That is, broad grants of delegated authority are four times more common than narrow grants. Descriptive statistics for this and other predictor variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for the independent variables

# indicates time variant variable.

We also include a number of additional independent variables in our analyses, which we group together into four main clusters: congressional ex ante, congressional ex post, DOI and environmental variables. With regard to congressional ex ante variables, we first account for whether a statute includes a Deadline. Deadlines are inserted in some statutes to speed up the agency’s regulatory responsiveness and thus may serve to reduce the time to NPRM. Our models also incorporate a count of the congressional Hearings Ex Ante, which are held on the authorising statute but prior to its passage. A larger number of ex ante hearings may signal greater evidence of congressional interest to the agencies. Finally, more complex statutes may require more time to implement (Statute Complexity). We account for this possibility by including the number of statute pages.

Congressional attention after the passage of a bill (i.e. ex post oversight) may also hold influence over the timing of draft agency regulations. Similar to congressional hearings prior to a statute’s passage, a hearing held on a statute after its passage into law may signal continued congressional attention to an agency. We thus include a count for the number of Hearings Ex Post. The lead sponsors of the statute from both chambers may also play an important role, and we account for them still being in Congress at any point across analysis time with two indicator variables.Footnote 4 Lasting congressional coalitions may influence regulatory timing as well. Therefore, we measure whether the Partisan Coalition in place when the statute was passed remains in power. This variable thus taps changes to the majoritarian make-up of the partisan coalition in Congress across time. It scores a 1 as long as the original majoritarian circumstances in Congress remain the same as at the statute’s passage and is coded a 0 thereafter.

A large department like DOI is tasked with a multitude of duties at any given point in time, and the ability of the department to accomplish these tasks is affected by its resources and its workload. Rulemaking is no exception. Thus, we include the number of DOI Employees in Washington, DC, the hub of DOI rulemaking, in our models. More employees may augment the department’s ability to respond to a new delegation of authority. At the same time, the Workload Accumulated, which we calculated as the accumulated number of statutes requiring a regulation that have not received one, may have the opposite effect of slowing down an agency’s progress. Finally, agencies that issue more rules may have more experience with rulemaking and more systems in place and thus react quicker to new congressional authorisations. Consequently, we include the annual number of DOI NPRMs in our analyses.

Environmental factors may also exert influence on the time from statute to NPRM. For one, important statutes may draw more attention from the agency and thus encourage quicker regulatory activity (called Statute Significant). Hence, we include the number of scholarly citations to a particular statute, which suggests its relative consequence.Footnote 5 We also create Initial Administration, which is coded a 1 as long as the party of the president at the statute’s passage remains the same and scores a 0 thereafter. Moreover, we also interact this variable with the previously described Partisan Coalition. In order to properly account for political time, we develop and include a measure, Time to Presidential Election, which is the time in days from the authorisation statute to the first presidential election after statute passage.Footnote 6 Finally, a number of studies have focused on the role that unified or divided government plays in delegation and discretion (Epstein and O’Halloran Reference Epstein and O’Halloran1999; Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis2002; Farhang and Yaver Reference Farhang and Yaver2016). Thus, we include an indicator for Unified Government at passage.

Methods

We employ event history methods that are innovative within political science. Specifically, we rely on Royston-Parmar models, which are commonly used in the medical literature. In many respects, Royston-Parmar models (Royston Reference Royston2001; Royston and Parmar Reference Royston and Parmar2002; Lambert and Royston Reference Lambert and Royston2009; Royston and Lambert Reference Royston and Lambert2011; Haeder Reference Haeder2019) provide a sound middle ground between the semiparametric Cox model and a fully parameterised approach. One advantage is Royston-Parmar models improve on the noisy hazard and survival functions of the Cox models, as well as the Kaplan-Meier and Nelson-Aalen estimators, which allows for easier interpretation. Moreover, Royston-Parmar models estimate a baseline hazard and thus allow us to utilise information contained in the baseline across the observation period. Thus, we can evaluate absolute as well as relative risk. Royston-Parmar models also provide added flexibility over parametric models. This flexibility allows complex hazard functions and the estimation of classes of models beyond traditional regression approaches. Conveniently, the various scales reduce to Weibull, loglogistic and lognormal models when warranted. Moreover, unlike many parametric models, they are not monotonic in their hazard functions and may have more than one turning point. Another advantage is that Royston-Parmar models are also not restricted to the proportional hazard assumption; they are estimated by full maximum likelihood, and Akaike’s Information Criteria (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) can be used for comparisons.

Importantly, Royston-Parmar models allow us to study the changing hazard of rule promulgation over time – which may vary considerably across analysis time. After all, some variables may be quite meaningful immediately after statute passage, while others may materialise only as significant after some time has passed. Given this critical feature of Royston-Parmar models, the data relationships are best shown in graphs that allow the researchers to display the changing hazard by plotting them over time. Consequently, we use several graphs in the article to display our results. As the reader will see, the graphs allow for easy discernment of both statistical and substantive significance and can be created while strategically varying other covariates to mimic “real world” scenarios. Positive coefficients suggest that a predictor variable is associated with increased regulatory responsiveness – wherein greater responsiveness is operationalised as a shorter amount of elapsed time between Congress’ authorisation of an agency action and the agency’s supply of that action. Negative coefficients suggest slower rule production. We will note here that the coefficients that we present in the article provide information regarding the overall statistical significance of the predictor variables. However, some variables may only be significant early in a rule’s life course, while others may become significant only late. Still others may be displayed in the table as, on average, statistically insignificant but may reach the significance threshold at certain points across analysis time. Given this, we also present our key findings in graphical form, which allows the reader to readily appreciate these patterns. Statistical significance is established at standard discipline levels.

Results

Hypothesis 1: Variation in delegating statutes

We provide the first sophisticated quantitative examination of the timing of agency regulations in response to varying congressional delegations of regulatory authority. Our key results are displayed in Figures 1 and 2 and Table 2. In our first and key hypothesis, we theorised that the breadth of the statutory delegation of policymaking authority in the original enabling legislation conditions the timing of agency regulatory responsiveness. In particular, we suggest that a parsimonious way to understand agency responsiveness to legislative policymaking delegation is to concentrate on the modal operators – such as must and may – found in delegating statutes.

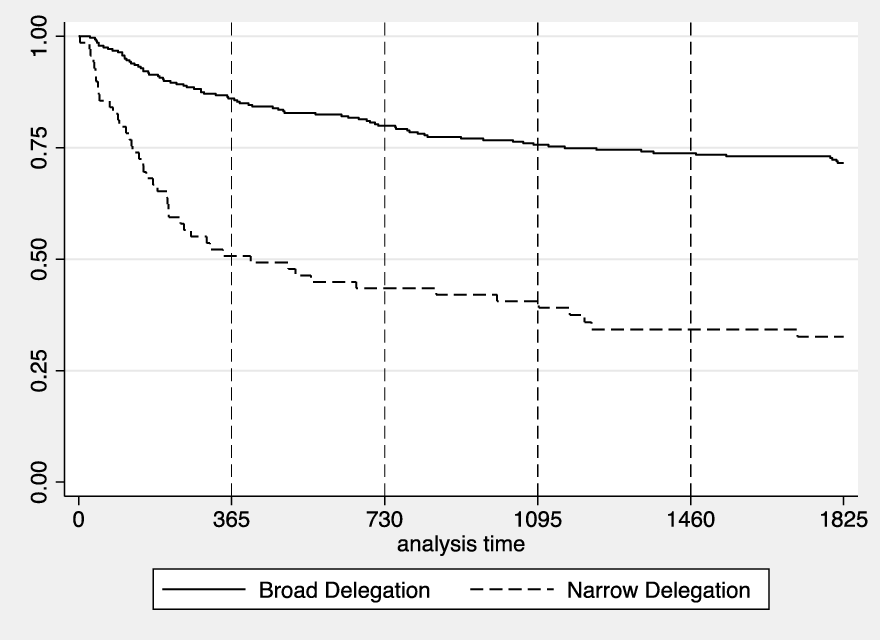

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier survival estimates: narrow versus broad delegation.

Note: Kaplan-Meier estimates are shown for the first 1,815 days for illustrative purposes. Results are statistically different from each other at conventional levels. Confidence bounds are omitted for clarity.

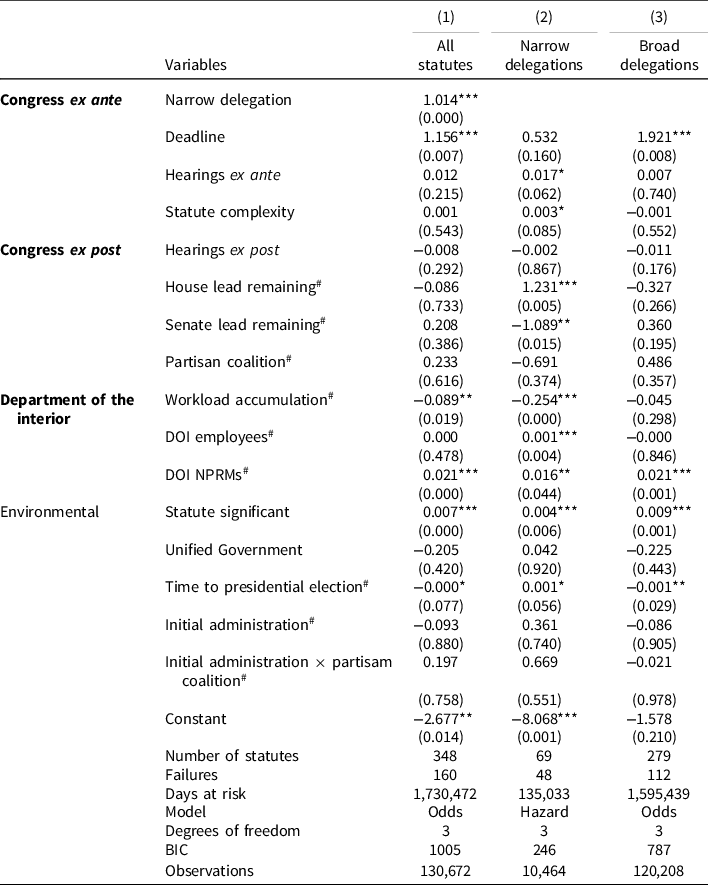

Table 2. Time passage from legislation to regulation

All models are flexible parametric survival models; p values in parentheses; #indicates time variant variable; *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

We find strong support for Hypothesis 1 in Figure 1. Figure 1 uses Kaplan-Meier nonparametric estimators to assess the promulgation of NPRMs across our two key conditions of interest: narrow and broad delegations. As hypothesised, statutes with narrow delegations appear to trigger agency rules much more quickly than statutes with broad delegations. The differences are significant at conventional levels. Overall, the dashed line is initially much steeper than the solid line; this suggests that agency officials provide more attention to required regulatory delegations in the months and years immediately following this type of delegation statute than to rules citing more permissive statutory authority. In looking at the one-year mark, about 50% of statutes with narrow delegations have produced a regulation, while substantively less than 20% of those with broad delegations have done so.Footnote 7 At the four-year mark, the number increases to 60% for the former and remains around 25% for the latter. Additionally, as implied by our theoretical argument, across the full survival estimate, the dashed line is consistently and substantively below the solid line. This result implies that across analysis time, the risk of rule promulgation is higher for rules with narrow delegations compared to those with broad delegations.

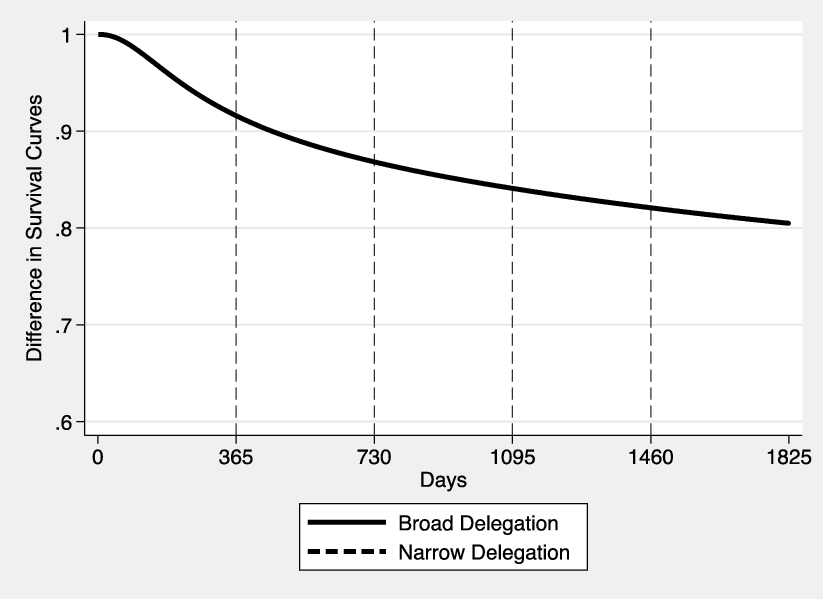

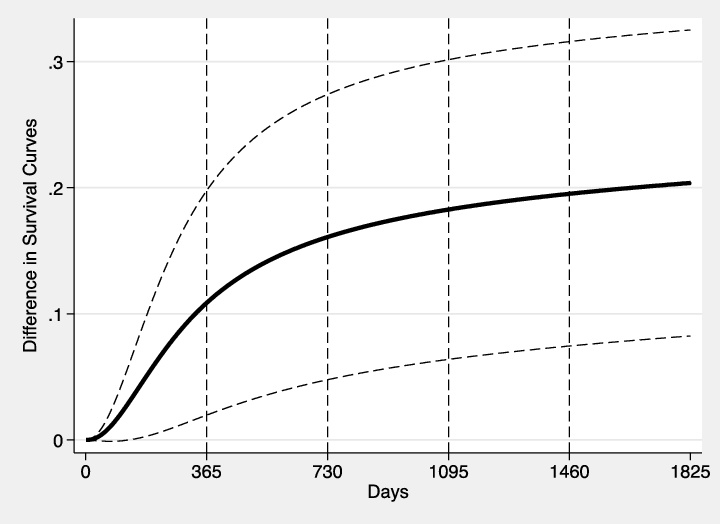

We find further support for Hypothesis 1 in Table 2, Model 1 (and the corresponding Figures 2a and 2b), which provides the fully specified event history model predicting regulatory timing using the DOI data with all covariates described above. It allows us to assess whether or not the breadth of the statutory delegation distinction, which stands out in the Kaplan-Meier estimates, remains a critical factor once a variety of other predictor variables are included in the specification. Our expectation is that a Narrow Delegation will trigger a draft agency regulation much more quickly than a discretionary statute. And we see suggestive evidence of this pattern: the coefficient for Narrow Delegation is positive and statistically significant. This indicates that Congress may increase regulatory responsiveness when it requires an agency to write a rule, as opposed to permitting it to write a rule. To further explore the effect of Narrow Delegation, we plot the survival curves across analysis time for broad (solid line) and narrow delegation (dashed line), while setting all other variables to their mean or modal values, as appropriate in Figure 2a. Figure 2b then presents the difference between these two survival curves, which is the measure of interest in testing the hypothesis and assesses whether that difference is statistically different from zero. Specifically, the solid dark black line presents the difference between the survival curves for the two values of the variable whereas the dotted lines provide the 90% confidence interval. The figure’s initial steep upward trend line implies that delegating statutes containing a “shall” or “must” requirement, as opposed to a “may” (or similar) delegation, trigger DOI action at a much faster pace over the first years of analysis time. After that, the line flattens out but nonetheless continues to increase. In short, we find consistent support for our main argument that the type of delegation has significant and substantial effects on the timing of NPRMs.

Figure 2a. Survival curves for broad and narrow delegation in model 1.

Note: Narrow Delegation is varied from 0 to 1. All other variables are set at their mean or mode.

Figure 2b. Difference in survival curves for narrow delegation in model 1.

Note: Narrow Delegation is varied from 0 to 1. All other variables are set at their mean or mode.

Hypothesis 2: A focus on narrow delegation

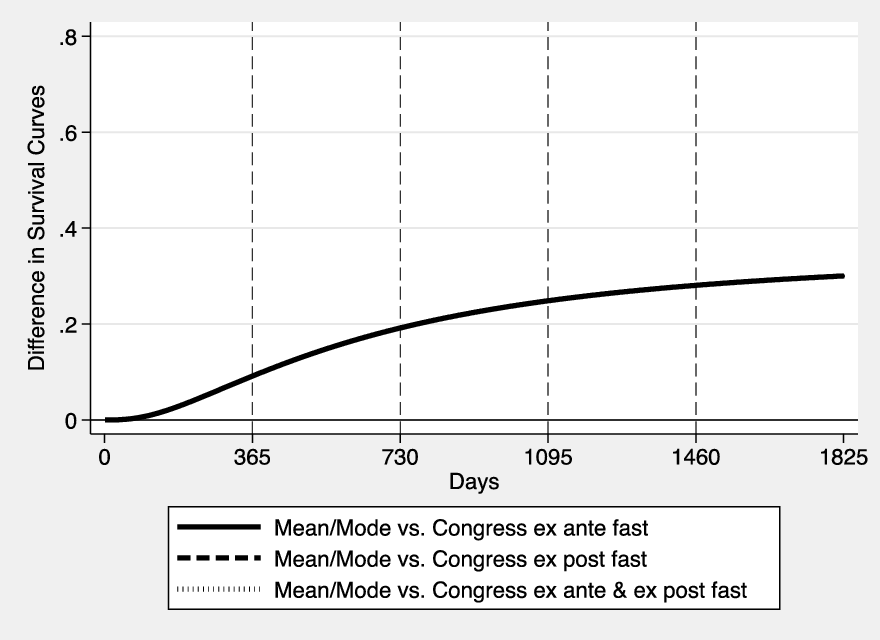

As outlined above, we also hypothesised that when a narrow delegation is paired with other clear signals from Congress regarding its interest in a statute, it will work to further speed up agency action. We rely on the Model 2 specification to test this hypothesis. As we mentioned earlier, one of the advantages of the graphical display and interpretation this modelling technique allows is that we can use it to model scenarios in the data. For instance, using the Model 2 specification that is for narrow delegations, we can plot the risk of rule promulgation when all the Congress ex ante variables are turned “on,” which we do in Figure 3. By “on”, we mean a scenario where all of the variables work to speed up draft rule promulgation.Footnote 8 We can then compare this Congress ex ante scenario to the baseline scenario for Narrow Delegation, which is a scenario where all other variables are set to their mean and modal values. As described above, we can then compare these two survival curves and determine whether the difference between the two curves is statistically different from zero. We can also repeat this analysis by comparing the baseline to the scenario where all the Congress ex post variables favour swift promulgation, again assessing whether the difference between the two curves is statistically different from zero. Finally, we can combine the ex ante and ex post scenarios and compare them to the baseline scenario.

Figure 3. Differences in survival curves comparing baseline to various scenarios for model 2.

Note: Confidence intervals are omitted. Scenarios are statistically different from baseline except for a period after the statute is passed. For all scenarios, we varied the values of the respective variable between large and small values while holding all other variables at their mean or modal value.

We rely on the display of differences in survival curves, which are presented in Figure 3, to assess our hypothesis. In Figure 3, the Congress ex ante scenario (versus the Narrow Delegation baseline scenario) is displayed by the solid line, the Congress ex post scenario (versus the Narrow Delegation baseline scenario) by the dashed line and the combined scenario (versus the Narrow Delegation baseline scenario) by the dotted line. All three scenarios are statistically different at the 90% level from the baseline (except for a period immediately after passage of the statute) providing solid support for Hypothesis 2. Legislation with a narrow delegation can work in concert with ex ante and ex post congressional actions to accelerate the timing of regulations. Indeed, under the high ex ante and ex post scenario, the probability of promulgation increases by roughly 0.1 at the one-year mark and continues to increase thereafter. Consequently, while both ex ante and ex post factors individually speed up promulgation, the combined effect is substantial: the difference in probabilities reaches 0.3 at the one-year mark for the combined scenario and continues to grow swiftly for about another two years before flattening out.

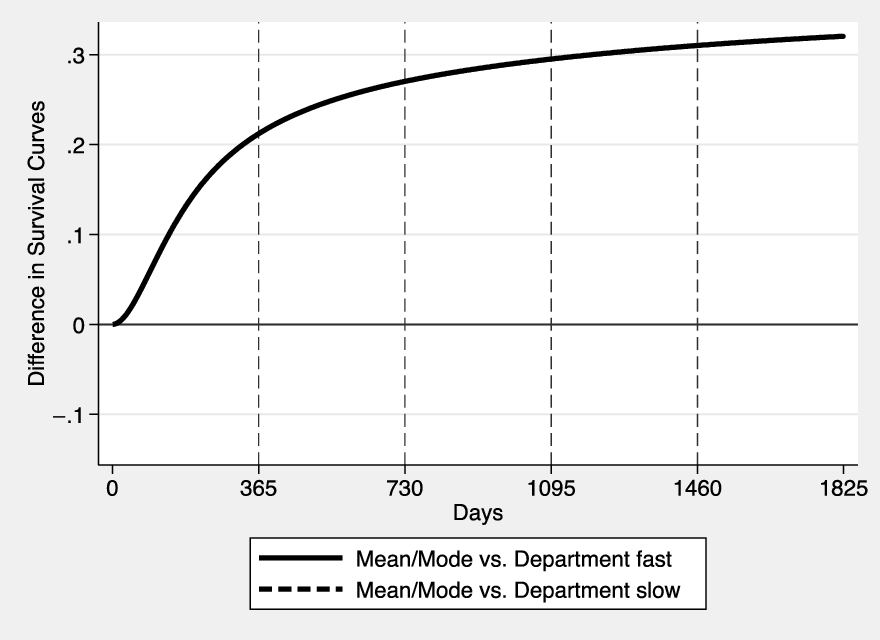

Hypothesis 3: A focus on broad delegation

Finally, we hypothesised that the bureaucracy’s internal considerations – such as its regulatory experience and contemporaneous resources – will be key drivers of rule timing when a statute provides a broad delegation of policymaking authority to the bureaucracy. We rely on Model 3, which focuses on statutes with broad delegations, to test this hypothesis. To assess this argument, we study the scenario when all the DOI variables are turned “on” (i.e. set to speed up a draft rule’s issuance) while the other model variables are set to their mean or modal values, and then we compare the survival curve to the baseline model. The results are shown graphically in Figure 4. The key relationship is displayed as a solid line. As expected, the difference between the survival curves is positive, indicating that with the DOI variables turned “on”, rules are issued faster. The difference in the survival curves reaches conventional levels of statistical significance (except for a period immediately after passage of the statute). We also tested the opposite scenario, that is we compared the circumstances where all DOI variables are turned “off” (i.e. set to slow down a draft rule’s issuance). The differences in survival curves (the dashed line in Figure 4) are once more statistically significant at the 90% level, but this time below zero, indicating a slowing down of rule issuance. We also note that, compared to the baseline, the effect of turning the DOI variables “on” appears to have a more substantial effect than the inverse scenario where they are turned “off.” In short, for statutes that have a broad delegation of authority, our findings indicate that when internal considerations are primed for an agency to write draft rules, agencies issue them more quickly. Yet, the inverse holds, too.

Figure 4. Survival curves comparing baseline to department fast and department slow for model 3.

Note: Confidence intervals are omitted. Scenario “Department slow” is statistically different from the Mean/Mode scenario except for a very brief period early on.

Other findings

Several other patterns are of interest in Table 2, Model 1. Take, for instance, the results attached to Unified Government. While this construct is not a focus of our theorising, it is a critical predictor variable in numerous studies focused on the delegation-discretion relationship (Epstein and O’Halloran Reference Epstein and O’Halloran1999; Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis2002; Farhang and Yaver Reference Farhang and Yaver2016; Revesz and Davis Noll Reference Revesz and Davis Noll2019; Bertelli and Doherty Reference Bertelli and Doherty2019). Interestingly, we find no evidence of Unified Government affecting draft rule timing. It is statistically insignificant in Table 2, Model 1 (as well as in Models 2 and 3). Moreover, graphical displays of this variable show no evidence that it emerges as significant at any point across analysis time (omitted). While we use a time invariant measure of Unified Government, in analyses not shown, we have swapped out this metric for a time varying one. Again, Unified Government does not emerge as a meaningful predictor variable in the data.Footnote 9

Time to Presidential Election is statistically significant in all three models; however, it changes signs across the model specifications and holds little substantive effect on NPRM issuance when we compare it graphically to the baseline models (omitted). Partisan Coalition, Initial Administration and the interaction between Time to Presidential Election and Initial Administration are not returned as statistical and/or substantively important variables across the model specifications. These findings are derived from many decades of agency policymaking; however, the data’s conclusion point in 1990 may affect the generalisability of the results to more modern times. In the case of Initial Administration, for instance, research on the administrative presidency (Moe Reference Moe, Chubb and Peterson1985; Durant Reference Durant1992; Moe and Wilson Reference Moe and Wilson1994) suggests that the tools of the presidency have advanced across time and in ways that may make the modern president a more potent political principal of the federal bureaucracy than in the past (Lewis Reference Lewis2008; Resh Reference Resh2016).

In results not shown, we also undertook the time-intensive step of integrating variables measuring the presence of each statute’s enacting coalition into the main model specification. First, we collected data on every member of the House and Senate who was listed as cosponsor for each DOI delegating statute. We then created time-varying variables for the remaining cosponsors in both the House and Senate across analysis time and reestimated our models. To account for potential censoring because cosponsorship was substantially limited in the House before 1967 (Koger Reference Koger2003), we reestimated the models starting in 1967.Footnote 10 These additional variables did not increase the contemporaneous risk of draft rule promulgation. Second, we collected data for every House and Senate member who voted for the DOI delegating statutes at passage and then tracked when these members left office. In doing so, we were able to assess which members of the enacting coalitions for each statute remained in office across our full-time analysis (i.e. 1950–1990). Similar to the results above, having a majority of the original enacting coalition (i.e. those voting for statute passage in the House or Senate) still in Congress at any point across time does not increase the risk of NPRM issuance.Footnote 11

Conclusion

We live in an era of delegated lawmaking. And this observation is perhaps best illustrated in our lived experience: people in the US are much more likely to interact with the policy decisions made by public agency officials than those made by elected legislators (Kaufman Reference Kaufman2001). “Indeed, regulations frequently play a more direct role than statutes in defining the public’s legal rights and obligations” (Manning Reference Manning1996). Or, as Mashaw (Reference Mashaw1999) puts it, “Much of public law is legislative in origin but administrative in content.” We study the connection between the legislative origins and the administrative manifestations of public policy in this article. In doing so, we shed new theoretical and empirical light on the link between the congressional delegation of policymaking authority and agency discretion.

When does legislation trigger regulation? We conceptualise agency policy responsiveness via the timing of draft agency rules, and we theorise a distinction between statutes that provide a narrow delegation of autonomy from those that provide a broad delegation. Importantly, we suggest that this statutory difference is a parsimonious way to understand the scope of the original legislative act, and we expect it to hold policy effects for the timing of regulations. Specifically, due to Congress’ (and the courts’) many review powers, when Congress expressly directs an agency to promulgate a rule, we anticipate a quickened agency reply. However, when Congress provides greater discretion to an agency – such as authorising that it “may” issue a rule – we hypothesise the opposite effect. We then provide the first quantitative examination of the timing of agency regulations in response to varying congressional delegations of policymaking authority. We use data from almost 350 statutes across four decades, which are matched up with thousands of agency rules. We focus on the legally binding policy actions of the US. DOI, which has a wide-ranging regulatory mandate. Our analyses allow us to simultaneously measure the efficacy of numerous commonly referenced drivers of bureaucratic responsiveness, and we employ innovative event history methods.

Our primary results provide much needed new evidence with regard to the timing of the legislature’s statutory demand for regulation to the bureaucracy’s supply of regulation. Specifically, we find strong evidence that statutory breadth matters to rule timing. Statutes that obligate agencies to write rules illicit a much quicker regulatory reply from agencies than those that provide permissive grants of regulatory authority. Indeed, almost 50% of statutes with a narrow delegation produce a rule within a one-year time period. These findings are particularly noteworthy because changes to statutory wording do not require significant congressional resources but do appear to hold substantial effects on rulemaking. Moreover, when Congress combines this type of obligatory delegation language with other signals of congressional attention – before and after a statute is passed – agency responsiveness is achieved even more quickly. For cases when Congress provides a broad delegation of authority in a statute, we uncover evidence for our hypothesis that internal agency considerations are key drivers of rule timing. When taken together, these findings paint a new picture of the connection between delegation and discretion.

This article advances knowledge by providing new theorising and evidence, and hence, it provides a critical reply to West and Raso’s (Reference West and Raso2013) calls for a greater focus on the role of Congress in directing agency rulemaking. We have known for some time that agencies hold a great deal of control over the timing of agency policymaking (Carpenter et al. Reference Carpenter, Chattopadhyay, Moffitt and Nall2012; Sunstein and Vermeule Reference Sunstein and Vermeule2014; Potter Reference Potter2017). We have also known that the timing of agency regulations is a policy and a political act, which is often controversial and consequential (Revesz and Davis Noll Reference Revesz and Davis Noll2019). Our findings here indicate that Congress – in its original delegation regime choice – can hold great influence over that timing, and as a result, over agency policy responsiveness. Thus, our article provides one potential solution to the so-called “democratic deficit” that accompanies the gap in time between delegation and regulation (Adler and Walker Reference Adler and Walker2020).

Yet, our study is certainly not the last word on this subject. For instance, more research is needed to extend the article’s empirical analyses, across time and to multiple departments. We focus, for instance, on the administrative state immediately following the implementation of the APA; yet additional work is needed to see how these patterns play out today. It could be that in more modern times the practice of using the bureaucracy for its policy expertise has largely given way to other rationales for narrow or broad statutory delegation to agencies. In our contemporary world, for instance, Congress may use the bureaucracy to increasingly shift policy decisionmaking to agencies as a means to duck tough decisions (Weimer Reference Weimer2006; Hood Reference Hood2010). We have no way to test this hypothesis in our data. However, the extension of our approach in this article to more recent rulemaking activity would be an excellent first step toward teasing out modern delegatory practice. Moreover, our focus here is on legislative statutes that delegate new rulemaking authority to public agencies and the timing of the first agency proposed regulation that employs this delegated discretion. Future work ought to incorporate insights from Bertelli and Doherty (Reference Bertelli and Doherty2019) on the issue of reoccurring regulatory decisionmaking.

The hypotheses proposed and tested here also ought to be assessed in additional settings for their generalisability. For instance, our focus on DOI does not allow us to tease apart how presidential agency alignment (Clinton et al. Reference Clinton, Bertelli, Grose, Lewis and Nixon2012) may affect an agency’s promulgation of draft rules, or how the propensity of court interventions might affect an agency’s timing calculus. As a result, cross-department data are needed to explore such scenarios empirically. Moreover, similar research in the American states is needed, which, if accomplished, would allow for an evaluation of the theory we propose, as well as its interaction with the diversity present across state legislative institutions (including the presence of sunset or review provisions in regulatory authorisations in some states). Expansion of the work is also needed to yield greater insight into the connection between the bureaucracy’s internal considerations and rule timing. For instance, we focus on DOI’s regulatory experience and resources; however, other factors may also affect regulatory timing, especially for the broad delegations, such as the bureaucracy’s prioritisation of its on-going relationship with organised interests (Golden Reference Golden1998; Yackee Reference Yackee2006; West and Raso Reference West and Raso2013), agency insulation (Bertelli and Doherty Reference Bertelli and Doherty2019) or other contemporaneous political factors (Acs Reference Acs2015). Additionally, while our emphasis is on legislative agency relations, the president’s role in the regulatory process is receiving increased scholarly attention (e.g. Haeder and Yackee Reference Haeder and Yackee2018; Revesz and Davis Noll Reference Revesz and Davis Noll2019). Future work must integrate the president more fully into the theorising and empirical assessments of regulatory timing. Finally, there is also growing evidence that agencies often avoid the standard rulemaking process and instead may issue policy decisions via guidance documents (Raso Reference Raso2010; Haeder and Yackee Reference Haeder and Yackee2020c), which may be a different tool for fulfilling congressional demand for regulation.

The normative implications of our work are also far from settled. We know now that when Congress provides a clear delegation of regulatory authority, government agencies, at least those in our data set, tend to provide a speedy regulatory reply. This implies that legislation has a strong hold over regulation. Some observers will surely see this as a positive sign of congressional control of the bureaucracy. Yet, others may see the modal type of authorisation – broad delegations – to be problematic. After all, once rulemaking authority has been transferred, it is rarely rescinded and can be used at almost any point in time. Some will worry that such delegations are an abdication of lawmaking to a largely unelected and potentially unaccountable bureaucracy. Still others will view these same results as benign, suggesting that Congress often purposefully provides broad delegations. In doing so, it properly transfers power to an informed and expert bureaucracy to pursue its public mission, while balancing the need for delegation with democratic responsiveness and needed policy flexibility. Yet, regardless of what one sees – be it a handmaiden or not – this article adds new evidence to the scholarly and practitioner discussions by extending knowledge around a key debate in political science and policymaking: the relationship between delegation and discretion.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X21000180

Data Availability Statement

Replication materials are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/6RGQ88