Introduction

The defining features of psychiatric intensive care units (PICUs) appear to differ depending on the specific local development of services (Crowhurst & Bowers, Reference Crowhurst and Bowers2002). Although there are some inconsistencies in the definition of a PICU, their key differences compared to acute inpatient wards are that PICUs provide higher levels of staff input, more facilities and higher levels of security (Beer et al. Reference Beer, Pereira and Paton2001). People admitted to PICUs are younger, more likely to be male, have a history of substance misuse or violence, be experiencing a period of acute psychotic illness and to be detained under the Mental Health Act than those admitted to acute wards (Brown & Bass, Reference Brown and Bass2004). Finally, patients are more likely to receive antipsychotic medication, rapid tranquilisation, and seclusion (Brown & Bass, Reference Brown and Bass2004).

There is a small literature developing, which focuses on comparing the characteristics of PICUs and acute wards. Studies have found perceptual differences between staff in both environments. PICUs can be a challenging environment for staff to work in, with aggressive incidents towards both staff and patients being commonplace (Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Akhtar, Siddiqui, Shelley, Larkin, Kinsella, O'Callaghan and Lane2008). Higher numbers of PICU nurses report being the victims of violence than their colleagues on acute wards (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2007; Loubser et al. Reference Loubser, Chaplin and Quirk2009). Nurses working on acute wards are more likely to attribute problems, including violence, to drug and alcohol use than their PICU colleagues (Loubser et al. Reference Loubser, Chaplin and Quirk2009). Bowers et al. (Reference Bowers, Crowhurst, Alexander, Eales, Guy and McCann2003) studied the differences in the perspectives of acute and PICU nursing staff in relation to appropriate admissions for a PICU. They found that acute nursing staff took into account a smaller range of risk factors when considering admission and had a lower threshold for suitability when compared to PICU staff.

Patients have also reported higher rates of being assaulted on PICUs than acute wards (Loubser et al. Reference Loubser, Chaplin and Quirk2009). Furthermore, they reported that that aggressive behaviour on the ward is too quickly countered with medication, physical restraint or seclusion (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2007).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, differences of opinion have been found between staff and patients about how violent behaviour towards staff and patients is managed on mental health wards. The National Audit of Violence (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2007) found that staff were more likely than patients to feel that violence between patients was effectively managed, whereas patients were more likely than staff to feel that violence towards staff was managed effectively. Patients were significantly less likely than nurses to report problems with drugs and alcohol and link them with violence on a range of adult inpatient units (Chaplin et al. Reference Chaplin, McGeorge and Lelliott2006; Loubser et al. Reference Loubser, Chaplin and Quirk2009). Interestingly, nursing staff from both acute wards and PICUs reported more negatively than patients on the ward environment, for example, adequate space and temperature (Chaplin et al. Reference Chaplin, McGeorge and Lelliott2006).

It is of crucial importance that high quality care is delivered despite the challenging environment of the PICU. The Accreditation of Inpatient Mental Health Services (AIMS) quality improvement project was set up to raise standards of care in acute inpatient wards (Lelliott et al. Reference Lelliott, Bennett, McGeorge and Turner2006). AIMS is part of a wider quality improvement initiative coming from the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ College Centre for Quality Improvement (CCQI). The project was extended in 2009, alongside input from NAPICU (National Association of Psychiatric and Intensive Care and Low Secure Units), to monitor and improve care on PICUs (see Lemmey et al. Reference Lemmey, Bleksley, Cresswell and Lelliott2011).

This study aims to compare the quality of care on PICUs and acute wards by analysing questionnaires from the AIMS project measuring the experiences of patients, carers and qualified nursing staff. It is hypothesised that there would be more negative experiences from patients, carers and qualified nursing staff on PICUs compared with acute wards. The secondary aim of this study is to look specifically at quality issues on PICUs, including comparing the responses of patients and qualified nursing staff about their experiences in these environments.

Method

The AIMS project measures the quality of inpatient care against standards which have been developed by a steering group employing review of literature research, guidance and recommendations (Cresswell et al. Reference Cresswell, Hinchcliffe and Lemmey2010). There was then a process of consultation with stakeholders (Lelliott et al. Reference Lelliott, Bennett, McGeorge and Turner2006; Cresswell & Lelliott, Reference Cresswell and Lelliott2009). Initially the project recruited acute wards (referred to as AIMS-WA, AIMS for wards serving adults of working age) but this was extended to PICUs as the standards were adapted and modified. They are revised annually or as new guidance dictates; the AIMS-PICU are currently in their second edition.

Accreditation is achieved through an assessment of patient, carer and staff views as well as the ward environment, record keeping and trust policies. The ward undertakes a self-review, then a peer-review is conducted by a team which includes service users and carers. The Accreditation Committee reviews the data and their decision is ratified by the Special Committee for Professional Practice and Ethics. A detailed explanation of the AIMS process is available online (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2011).

Criteria for inclusion

All 22 acute wards and 22 PICUs with an AIMS peer-review between March 2010 and the end of June 2011 were included in this study. Anonymous questionnaires for patients and carers were sent to ward managers. They were instructed to distribute them and return them in freepost envelopes. Patients could request assistance from advocates but staff were instructed not to be involved. Staff questionnaires were completed online using login details that were separate to those for the ward manager. The response rate could therefore not be determined as the AIMS team did not have a record of the numbers distributed. Questionnaires had Yes/No responses, with the occasional N/A (full copies of the individual questionnaires can be obtained from the authors).

Analysis

The results were analysed using a chi-squared without Yates’ correction. For cases where N was lower than ten, Fisher's exact test was used. Due to the large number of items on the questionnaires that were subject to significance tests, a Bonferroni correction was used with the significance level set at p < 0.01.

During the period of data collection there were minor modifications to some of the items on the questionnaires for both types of unit. Analysis was therefore only conducted on those questions that remained the same. Additionally, standards were only included if they were the same for both AIMS-PICU and AIMS-WA. Analysis of the Staff Questionnaire was limited to items corresponding with the patient questionnaire plus those relating to key issues highlighted in AIMS reports (Cresswell & Lelliott, Reference Cresswell and Lelliott2009; Lemmey et al. Reference Lemmey, Bleksley, Cresswell and Lelliott2011).

Results

Within the time period specified, the following were received: 392 acute and 225 PICU patient questionnaires; 101 acute and 73 PICU carer questionnaires; and 213 acute and 238 PICU qualified nursing staff questionnaires. Tables 1–3 present the number of questions answered yes as percentages of the total number of answers to each question, not of the total number of questionnaires completed; respondents did not have to answer all questions.

Table 1 Quality standards measured by patient questionnaire with responses from acute wards and PICUs

*p < 0.01

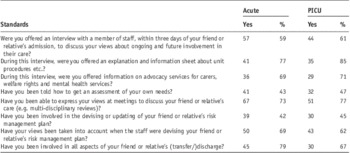

Table 2 Quality standards measured by carer questionnaires from acute wards and PICUs

Table 3 Quality standards measured by qualified nursing staff questionnaire responses from acute wards and PICUs

*p < 0.0001

Patient questionnaires

The results of the standards measured by patient questionnaires are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences in the compliance with any of the standards except regarding being able to leave the unit to attend other activities elsewhere, which was lower on PICUs. The other standards which included orientation, access to information and involvement in care planning, therapy and activities, medication management, personal space, and complaints showed no significant differences in compliance between acute wards and PICUs as measured by patient questionnaires.

Standards which were rated by more than 70% of patients on PICUs included orientation to the unit, being able to ask staff to explain when they didn't understand, and being able to use a telephone in private and being offered one to one time with staff. They also included being able to talk to staff about their medication and feeling that their dignity was taken into account when being given their medication.

Standards which were rated by less than 50% of patients on PICUs included being told how to access their records, receiving a welcome pack and being offered supportive counselling. The majority of standards (14/25) received ratings of compliance from 50–70% of patients on PICUs.

Carer questionnaires

There were no significant differences in ratings between the standards of care on acute wards and PICUs as measured by the carer questionnaires (Table 2). These standards included meeting with ward staff, provision of information, care planning, risk management and an assessment of their own needs.

Standards which were rated by more than 70% of carers on PICUs included feeling able to express their views in meetings, being offered information about the unit and information about advocacy. Standards which were rated by less than 50% of carers on PICUs included being informed how to get an assessment of their own needs or involved in devising risk management plans.

Qualified nursing staff questionnaires

Standards of patient care and staff training and supervision were measured by the qualified nursing staff questionnaire (Table 3). There were no significant differences in the compliance with standards between acute wards and PICUs except on the standard: ‘Patients being given the opportunity to have supportive one-to-one sessions with staff every day’. This was significantly more likely to occur on a PICU (Fishers exact test, p < 0.0001).

The only question for which qualified nursing staff PICUs answered ‘Yes’ less than 70% of the time concerned rehearsal of alarms.

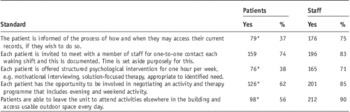

Comparison of patient and qualified nursing staff experience on PICUs

Responses from patients and qualified nursing staff on PICUs were compared (Table 4). This was only done on the questions that were measuring the same standard, i.e. patients’ access to records; one-to-one contact; supportive counselling; involvement in the therapy/activity programme and whether patients were able to leave the ward. Apart from one-to-one time, the opinions of patients and staff as measured by their questionnaires significantly differed for all of the standards (p < 0.001) with nurses rating them more positively.

Table 4 A comparison of responses between patients and qualified nursing staff on PICUs

*p < 0.001

Discussion

Main Findings

Overall, PICUs appear to be meeting standards relating to ward orientation, privacy and dignity and patients being able to talk to staff. Carers are able to express their views and are offered information about the unit. Findings for qualified nursing staff were particularly positive, with all but one standard answered positively by over 70% of respondents. However, areas for improvement are also highlighted. For patients, this concerns having access to information and involvement in care planning, therapy and activities, medication management and complaints. Carers rarely receive an assessment of their needs or are involved in risk management plans. Finally, PICUs are not rehearsing responses to alarm calls regularly.

Overall, there appear to be no significant differences in the key standards relating to quality of care that have been measured between PICU and acute wards. For staff, the only significant difference regarded more opportunity for one-to-one time with patients on a PICU. This might be expected as PICU provide higher levels of staff input (Beer et al. Reference Beer, Pereira and Paton2001).

Qualified nurses gave a more favourable opinion than did patients of all but one of the standards that they both rated. Reasons for this are unclear and warrant further exploration, but highlight the importance of obtaining a diverse representation of people who experience life on a PICU. One possibility is that the nurses are referring to their standard practice with patients as a whole and patients to their individual experiences.

Strengths and limitations

This study has a number of strengths. It has used a robust process which has developed questionnaires based on evidence-based standards and has included a large number of wards over England and Wales, giving representation from multiple centres and Trusts. Opinions from patients, carers and staff have been sought to give a holistic picture. However, the trusts and wards who took part volunteered to do so and may therefore not be representative of acute and PICU wards nationwide. There may also be a response bias in the completion of questionnaires by staff, service users and carers and the response rate could not be calculated.

Implications and conclusion

Previous literature comparing PICUs and acute wards is sparse, but has found differences in key areas (e.g. violence, drugs and alcohol, Loubser et al. Reference Loubser, Chaplin and Quirk2009; staff opinions on admissions, Bowers et al. Reference Bowers, Crowhurst, Alexander, Eales, Guy and McCann2003). Despite this, and the fact that PICUs are a more challenging environment, this does not appear to have compromised the quality of care that PICUs provide according to the methodology adopted. In summary, our data represent relatively high ratings of standards of care by nursing staff, but less so by patients and carers, that are similar for PICUs and acute wards. The experience of severe and acute mental illness in the PICU sample does not appear to jeopardise the quality of care received. Further work should focus on improving patient and carer experiences on PICUs and link their specific quality standards to clinical outcome.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Joanne Cresswell and Mike Crawford at the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Centre for Quality Improvement for their constructive comments on this paper.