The present article is the result of a larger research project launched by de Rosa in 1994, aimed at performing a meta-theoretical analysis of the scientific literature published on social representations theory (SRT) with the purpose of assessing the state of the art regarding the diffusion, dissemination and progression of this theory across time and geocultural contexts. By definition, SRT was designed to seize social realities dependent upon context, actors involved in creating, distributing and transforming them, and cultural and socio-political factors at play that may exert direct or indirect influence on said social constructs and dynamics; given the complexity and the vast number of dimensions covered by SRT, it has transcended the boundaries of one single discipline in its attempt at capturing multifaceted cultural phenomena (de Rosa, Dryjanska, & Bocci, Reference de Rosa, Dryjanska, Bocci and Khosrow-Pour2017b). Given the aforementioned strengths of SRT, it has become a research and conceptualization framework in multiple geocultural spaces around the world, including AsiaFootnote 1 (de Rosa, Reference de Rosa and de Rosa2013b), where there is a long-standing tradition of employing the theory in empirical studies on social objects indigenous to the Asian geocultural space, as underlined by several seasoned researchers (e.g. Liu, Reference Liu, Permanadeli, Jodelet and Sugiman2008; Liu & Sibley, Reference Liu, Sibley, Montiel and Noor2009; Permanadeli, Reference Permanadeli, Permanadeli, Jodelet and Sugiman2008) who chose to use SRT due to its theoretical and methodological versatility, which makes the theory apt to significantly contribute to the development of an original Asian social psychology, a goal shared among leading voices here, who argue that only by questioning universality and globalization in their epistemological and ontological premises may one truly capture local knowledge. Basically, we aim to see through a systematic analysis of publications whether SRT has indeed served as a tool to further context-specific knowledge of cultural and social phenomena in Asia, thus contributing to the enrichment of an original Asian social psychology; moreover, we will be able to assess through our analyses whether the theory itself has been employed in the Asian geocultural area according to its original European conceptualizations, and, respectively, operationalizations, or whether it has been adapted in order to meet the contextual societal and social needs here. Our results will shed light on both the potentiality of the theory to permeate the Asian geocultural area and on its usefulness as a future framework for researchers in this space dedicated to move beyond Western standards in an attempt to gain true insight on context-specific phenomena.

Literature Overview

Genesis and development of social representation theory

Born in France in 1950s from the initiative of Serge Moscovici, one of the founders of the European social psychology (Moscovici & Markova, Reference Moscovici and Markova2006), SRT has been of progressive interest to an emerging supra-disciplinary field (de Rosa, Reference de Rosa and de Rosa2013a, Reference de Rosa and Khosrow-Pour2017, Reference de Rosa2018; Jodelet, Reference Jodelet, Jodelet and Tapia2008a, Reference Jodelet2008b, Reference Jodelet2016; Lo Monaco, Delouvée, & Rateaux, Reference Lo Monaco, Delouvée and Rateau2016; Rateau, Moliner, Guimelli, & Abric, Reference Rateau, Moliner, Guimelli, Abric, Van Lange, Kruglanski and Higgins2011; Sammut, Andreouli, Gaskell, & Valsiner, Reference Sammut, Andreouli, Gaskell and Valsiner2015; Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Duveen, Farr, Jovchelovitch, Lorenzi-Cioldi, Markova and Rose1999) beyond the borders of social psychology, in dialogue with other social sciences.

The theory of social representations deals with explaining how people reconstruct social reality in order to control and adapt it, take action, and share it with others. It belongs to the social sciences, constituting a particular point of intersection between different disciplines; in particular, from the optics of social psychology, sociology and communication studies. However, it is open to the contribution of several disciplines, from humanities to natural sciences, due to its interest for many socially relevant study objects in cross-cutting thematic domains. As an expression of human and social relations, social representations are involved in the development of many aspects of daily thinking and provide an effective explanation for the origin and evolution of common sense. Social representations express, therefore, the “construction” of a social object, editable and reinterpretable by an actor who forms a part of a community. They play an essential role in communication and cannot exist without it, at the same time enabling communication and being generated, transmitted, and transformed through it. Also known as theories of common sense, social representations can be considered as organizing principles of the symbolic relationships between individuals and groups, as different members of a group share common knowledge on the object to which they refer in the course of conversations (de Rosa, Dryjanska, & Bocci, Reference de Rosa, Dryjanska and Bocci2017a).

The first field of interest of the theory was psychoanalysis and its image among different types of social groups and through the media press. Moscovici’s doctoral dissertation, later published as a book in French entitled Psychoanalysis: Its Image and Its Public (Reference Moscovici1961), laid the foundations for the theory, relevant until today. Although this seminal opera prima has been revised by the author and was published as a second edition in 1976, it took almost 50 years before the English version became available in 2008 (ed. G. Duveen), followed by other multilanguage integral editions, including in Portuguese/Brazilian (ed. P. Guareschi) and Italian (ed. A.S. de Rosa) in 2011. Alongside many other factors, this may have influenced the development of the theory in certain geocultural contexts rather than others.

Starting from Moscovici’s seminal work focused on the relation and mutual influence of science and common sense through communication, many related thematically oriented research fields and applied disciplines in the domains of health, environmental studies, education and sciences, politics, economics, and so on have been developed, with an impressive literature currently produced worldwide (de Rosa, Reference de Rosa and de Rosa2013b; de Rosa, Bocci, & Dryjanska, Reference de Rosa, Bocci and Dryjanska2018; Jodelet, Reference Jodelet, Jodelet and Tapia2008a, Reference Jodelet2008b, Reference Jodelet2016; Lo Monaco et al., Reference Lo Monaco, Delouvée and Rateau2016; Sammut et al., Reference Sammut, Andreouli, Gaskell and Valsiner2015). The genesis and transmission of social representations intersect the subjective, intersubjective and transsubjective dimensions within the social context in which the interactions are inscribed and within the wider public space (Jodelet, Reference Jodelet2015).

From theory to meta-theory of social representation: for a “biography of a theory”

De Rosa (Reference de Rosa1994) highlights three distinct levels at which social representations must be accurately comprehended: (a) as object of investigation and phenomenon of acquiring/elaborating the dynamic knowledge of our social worlds through interpersonal communication; (b) as theory comprising social representation’s conceptual definitions, constructs, processes, functions, the methodological approaches employed when investigating social objects, and the characterization of their adjacent constructs; and (c) as meta-theory, a critical examination of the coherence between the conceptual-epistemological inspiration by SRT and its operationalization in the empirical studies, as well as the series of objections that this theory has encountered over various aspects of its conceptualizations and the respective replies to the aforementioned critical objections.

In the 1990s, de Rosa initiated the arduous, never-ending task of archiving and registering in her library all available contributions inspired by the theory of social representations. This treasure of information has enabled her to propose a “biography of a theory” since its inception until the present moment in time and in different geocultural contexts, thus identifying different paths of its dissemination (de Rosa, Reference de Rosa2019, in press).Footnote 2

For a meta-theoretical analysis of the social representation theory in Asia

The current article presents the findings of the meta-theoretical analysis of scientific papers employing SRT from first authors affiliated to institutions in Asia. Asia does not represent a homogenous geocultural area given the high cultural diversity that characterizes this continent (Matsumoto, Reference Matsumoto2007), as well as its socio-political conflicts, as underlined by Liu and Ng (Reference Liu and Ng2007) in an editorial comment published in the Asian Journal of Social Psychology, where they argued for the lack of a political and economic motivation for unifying the Asian geocontext similar to the one characterizing the European Union, the multiple definitions of “Asia”, and the multidimensional identities in this continent. Indeed, the vast array of “national and supra-national identities” claimed by Liu and Ng (Reference Liu and Ng2007, p. 1) for Asia also applies to Europe – despite the role played for many decades by the European Union since World War II to harmonize countries – as well for other continents (e.g. North and Latin America). For the purposes of this article, we will be referring to Asia as a geocultural area, which refers also to societal context and not only to the geographic space, in line with de Rosa’s conceptualization (de Rosa, Reference de Rosa and de Rosa2013b) and with the ambition of many Asian researchers who seek to attain an identity for Asian social psychology (e.g. Atsumi, Reference Atsumi2007; Chiu, Reference Chiu2007; Leung, Reference Leung2007; Liu & Ng, Reference Liu and Ng2007; Liu & Sibley, Reference Liu, Sibley, Montiel and Noor2009; Matsumoto, Reference Matsumoto2007; Ward, Reference Ward2007).

As Kruglanski and Stroebe document in the 2010 Handbook of Social Psychology, social psychology has extended to the Asian context its Western conceptualizations via cross-cultural studies, which compared indigenous populations with Western ones, a trend that continued until the late 1960s when Asian researchers started a movement toward a distinct Asian social psychology, achieving visibility in the 1990s (Kim & Berry, Reference Kim and Berry1993). Indigenous psychologies approach human behavior and experience from a culture-specific angle in two ways: either departing from a certain cultural context and building theory and methods based on observed real life phenomena, or by departing from pre-existing theories and methods and adjusting them to the specific features of a certain cultural context (Enriquez, Reference Enriquez and Enriquez1990a, Reference Enriquez and Enriquez1990b). The dangers of employing the latter lie in an uncritical export of constructs for testing their external validity or for cross-cultural comparisons (Ward, Reference Ward2007), which has actually happened in the Asian context when social psychology first permeated this area, improving later when concern for the local study of culture was more apt for comprehending culturally sensitive phenomena. The situation of Asian social psychology was documented in an ample bibliometric study covering 46,545 scientific papers from 1970 to 2008 with at least one author affiliated to an Asian institution (Haslam & Kashima, Reference Haslam and Kashima2010); its findings revealed a steep growth in scientific production over time, a dominance of Hong Kong, Japan, India, Taiwan, mainland China, Singapore and South Korea in terms of volume, significant collaborations with US-based researchers primarily and other Anglo-phone spaces secondarily (Canada, Australia, the UK, New Zealand), an increasing trend in terms of local content and indigenous perspectives paired with a decrease in cross-cultural comparisons, and a thematic focus on personality and individual differences, culture, interpersonal relations, social cognition, emotions and applied topics (e.g. health) to the detriment of theoretical papers. Nevertheless, indigenous Asian approaches to theory and methods, and respectively, local empirical research are still scarce as compared to the use of theories and methods created and tested in other geocultural contexts (Haslam & Kashima, Reference Haslam and Kashima2010). Ward (Reference Ward2007) provided one potential explanation for this trend, as she echoed the crisis of social relevance undergone by psychology as a reason for the reluctance of developing nations to encourage research in this field.

In order to better understand the manner in which the Asian scientific community from social psychology appropriated SRT, it is worth noting how they position Asian culture and the subsequent manner of empirically addressing it within the global arena. Thus, while American social psychology was considered to be “individualistic” and European social psychology “societal”, Asian social psychology has been branded as “cultural” (Kim, Reference Kim1998), which implies that it was regarded in terms of its propensity and not its essence. As J.H. Liu and Ng (Reference Liu and Ng2007) argue, however, a truly Asian social psychology should describe cultural objects and social practices specific to this area and function for the improvement of this context in terms of practical ends. Basically, the authors argue that Asian social psychology may develop both from within and from outside the Asian context; no matter the case, the contributions have to be pertinent and applicable to this geocultural context and not mere replications of findings from mainstream psychology or field studies claiming to having been conducted within an indigenous framework, but with no theoretical or practical applicability.

Atsumi (Reference Atsumi2007) argues that there are multiple tensions and conflicting issues among and within nations, which makes it an ethical duty for social psychologists to focus more on humanitarian issues and hence create an applied social psychology. SRT has already proven its utility in explaining the dynamic interplay between ethnic, national and supra-national identities specific to this area, mostly modelled by past events and collective memories, which has made Asia “a natural laboratory for integrating and extending” (J.H. Liu & Ng, Reference Liu and Ng2007, p. 5) the premises and applicability of the theory, as it articulates harmoniously with indigenous historical knowledge. Exemplary in this respect are the contributions – among others – by Li Liu, where he explores the common thinking and communication of trust within the Chinese culture in its recent transformation by examining the notion of filial piety and its dynamic within a family context, the indigenous concept of guanxi within the sphere of self-other relations, the notion of loyalty within the sphere of individual-state relations, the role of money as deputy agent of trust in the context of China’s transition to market economy (L. Liu, Reference Liu, Marková and Gillespie2008a); or when he analyses the social representations of quality of life in China, embedded in its collective memory organised around the central themata of “having/being”, as both antonymic and dialogically interdependent “economic/existential” interpretative repertories overarching generative and normative power over the social discourse (L. Liu, Reference Liu2008b), or when he looks at the yang and yin in communication and persuasion (L. Liu, Reference Liu2008c). Even when traditional constructs, such as stigma, bias, stereotypes, prejudices, intergroup relation, social-national-ethnic identities, social dominance, intergenerational system of values and social practices, action research and so on are taken from social, cross-cultural or political psychology, the special way to look at their societal nature and way of functioning in cultural contexts in the light of SRT is well exemplified in other contributions, including – among many other authors – Guan (Reference Guan2006), Guan and Dai (Reference Guan and Dai2011), Guan and Liu (Reference Guan and Liu2014), Huang (Reference Huang2008), Huang, Liu, and Chang (Reference Huang, Liu and Chang2004), J. Liu (Reference Liu, Permanadeli, Jodelet and Sugiman2008), and J.H. Liu and Sibley (Reference Liu, Sibley, Montiel and Noor2009).

At the 9th International Conference on Social Representations that took place in Bali, Indonesia in 2008, Permanadeli further developed the applicability and utility of employing SRT for the empirical studies of social objects indigenous to the Asian geocultural area. She notes that since the creation of SRT in 1961 by Moscovici, the theory has developed in both theoretical and applied aspects, not only in its “homeland” Europe, but also in the Americas and more recently, in Australia, Asia and Africa, mainly due to its ability to transcend the individualistic approach to social psychology by offering a holistic perspective of both social and cultural dimensions in the study of common sense knowledge, which is highly relevant for culturally diverse contexts such as Asia. At the same scientific event, J. Liu (Reference Liu, Permanadeli, Jodelet and Sugiman2008) added that the Asian tradition of conducting research in social psychology does not promote method over content, which is in line with Moscovici’s (Reference Moscovici and Duveen2000) prescriptions for SRT: “methods are only means towards an end. If they become an end or a criterion of the selection of topics and ideas, then they are just another form of professional censorship” (p. 268). Furthermore, in 2009, J.H. Liu and Sibley (Reference Liu, Sibley, Montiel and Noor2009) underlined once again the value of SRT for empirical research in the Asian geocultural area, fulfilling Atsumi’s (Reference Atsumi2007) standard to produce results that are truly useful for the development of the social communities under study. For example, looking at the SRT anchoring and dissemination in China, Jian Guan (Reference Guan2015) observes that since 2000 to present: “Much recent Chinese psychological research has been closely linked with economic and social reform, technological developments and application of psychology” (p. 24).

Given all of these aspects, in line with the purpose of meta-theoretical analysis as well as with the specificities that characterize the Asian geocultural area, we set out to address the following research questions: How did SRT develop in Asia across time and space? How was SRT appropriated conceptually and in relation to other theories? How was SRT used empirically? What are the thematic areas addressed by SRT in the Asian context? Previous research conducted by de Rosa provided a comprehensive picture of the development of SRT globally, across time, space, thematic areas and paradigms (see de Rosa, Reference de Rosa and Garnier2002, Reference de Rosa and de Rosa2013b, Reference de Rosa2018; de Rosa & d’Ambrosio, Reference de Rosa and d’Ambrosio2008). Regarding the Asian geocultural area, she found in 2009 an upsurge in the number of publications subsequent to the 5th International Conference on Social Representations, as well as a majority of publications primarily authored by Chinese researchers, followed by Japanese and South Korean ones (de Rosa, Reference de Rosa2005–2019). In 2013, she found that SRT was used at a worldwide level less frequently and more generically in the Asian and African contexts (de Rosa, Reference de Rosa and de Rosa2013b); while in 2015 de Rosa found that the papers first authored by researchers affiliated to institutions in North America, Asia and Oceania tend to be included in journals indexed in SCOPUS and WoS more frequently compared to papers first authored by researchers affiliated to institutions in Europe and Latin America (de Rosa, Reference de Rosa2015b, Reference de Rosa, Lo Monaco, Delouvée and Rateaux2016a; de Rosa et al., Reference de Rosa, Dryjanska and Bocci2017a, Reference de Rosa, Dryjanska, Bocci and Khosrow-Pour2017b, de Rosa, Dryjanska, & Bocci, Reference de Rosa, Dryjanska, Bocci and Khosrow-Pour2017c). Since these results were found for publications employing SRT from all geocultural contexts, we aim to provide a comprehensive picture on the state of the art of SRT in Asia.

Method: Data Sources and Multilevel Strategies of Analysis

For this article, 194 publications – selected on the basis of affiliation of the first author to an Asian institution – were extracted from a wider corpus of more than 10,000 bibliographic references filed in the So.Re.Com “A.S. de Rosa”@-library, “a digital platform integrating scientific documentation, networking and training purposes in the field of Social Representations and Communication” (de Rosa, Reference de Rosa2015a, p. 4938).

All of the papers in our corpus were subjected to meta-theoretical analysis, performed until 2016 using the Grid for Meta-Theoretical Analysis (created by de Rosa in Reference de Rosa1994 and last updated in February 2014), which requires the researcher to note the presence or absence of several indicators included in six sections: (1) bibliographic and bibliometric meta-data; (2) references to constructs/concepts related to SRT; (3) references to constructs/concepts pertaining to other theories and disciplinary approaches; (4) thematic areas (and specific objects of study); (5) methodological profile, and (6) paradigmatic implications (for a comprehensive description of the Grid, see de Rosa, Reference de Rosa and Garnier2002, Reference de Rosa and de Rosa2013b).

The data analyses have been conducted pursuing multistep strategies:

(1) Descriptive profile of findings and geomapping performed by Tableau Desktop (http://www.tableausoftware.com) to visualize some of the results about the bibliometric impact of the scientific production country by country, and overall production at the worldwide global scale.

(2) Beyond the descriptive level, the data compiled with the Grid was subjected to Ward’s hierarchical clustering (HC) on the top of principal components analyses conducted with R software 3.3.2, the package FactoMiner, to offer the structural multidimensional view of the significant intersection between “metadata” (detected by section 1 of the Grid: Bibliographic item) and “data” detected by sections 2–6 of Grid concerning the meta-theoretical analysis of the texts from the theoretical, thematic, methodological, and paradigmatic point of view), used respectively as “illustrative” and “active” variables.

Results and Discussion

Descriptive profile and geomapping

The graphs and tables below show the absolute frequencies and/or percentage distribution of the bibliographic sources by some of the variables selected from the first section of the Grid (bibliographic item), including:

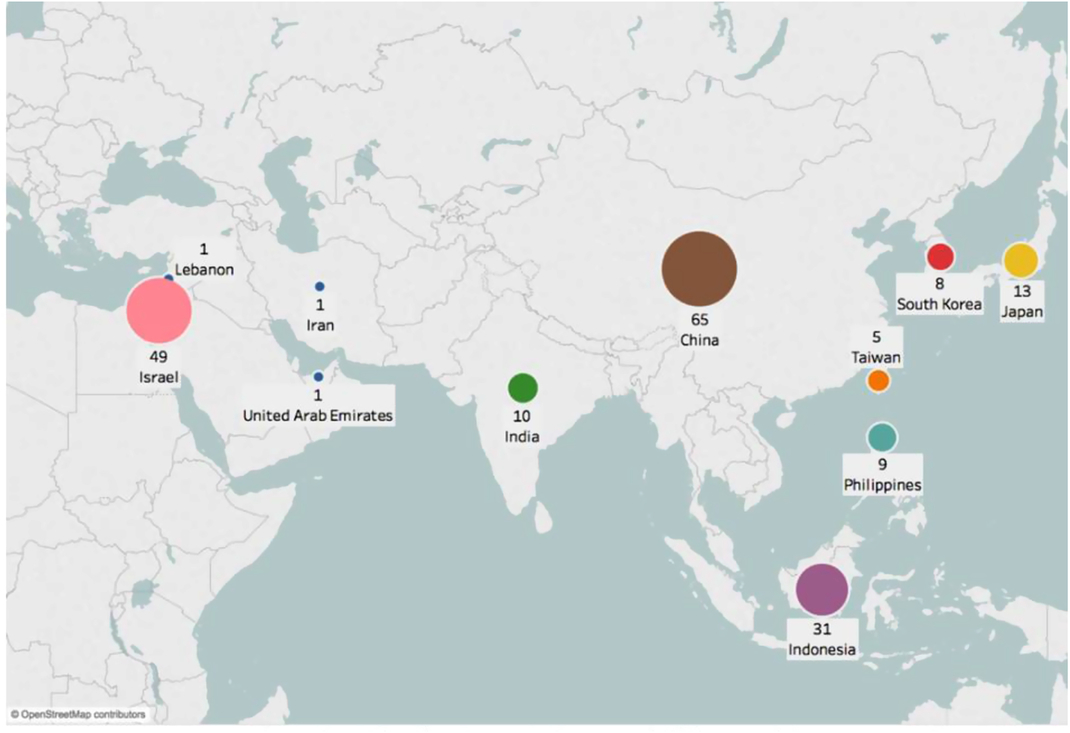

First author’s institutional affiliation – Country. This shows the dominance of publications by first authors from China, Israel, Indonesia, Japan and India (F higher than 10), followed by first authors from other Eastern countries (the Philippines, South Korea, Taiwan) and Middle East (Iran, Lebanon, Turkey and United Arab Emirates; F ranging from 9 to 1; Figure 1).

Figure 1. Geomapping the distribution of the 194 bibliographic sources from Asia by “First Author’s Institutional Affiliation – Country” in Tableau Desktop 10.3.

Resource type. This shows the high prevalence of “papers” and “conference presentations” compared to “book chapters”, also in line with the general trend of publishing strategies in the bibliometric era, and the “Language of publication”, showing a clear dominance of English, followed by Chinese and rarely by French and Japanese (see Table 1). Liu and Ng (Reference Liu and Ng2007) offer several reasons for the result of English as the most employed language for publication: access to scientific literature from other geocultural contexts conditioned upon an advanced knowledge of English; most of the prominent researchers in Asia have taken their studies in Europe or the US; and last, but not least, increasing pressure for researchers to publish in social science citation-indexed outlets.

Table 1. Distribution of bibliographic sources by ‘resource type’ and ‘language of publication’

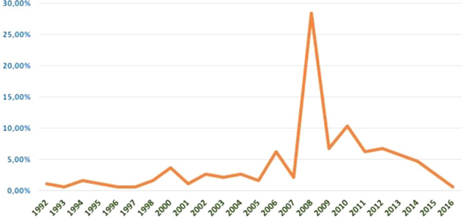

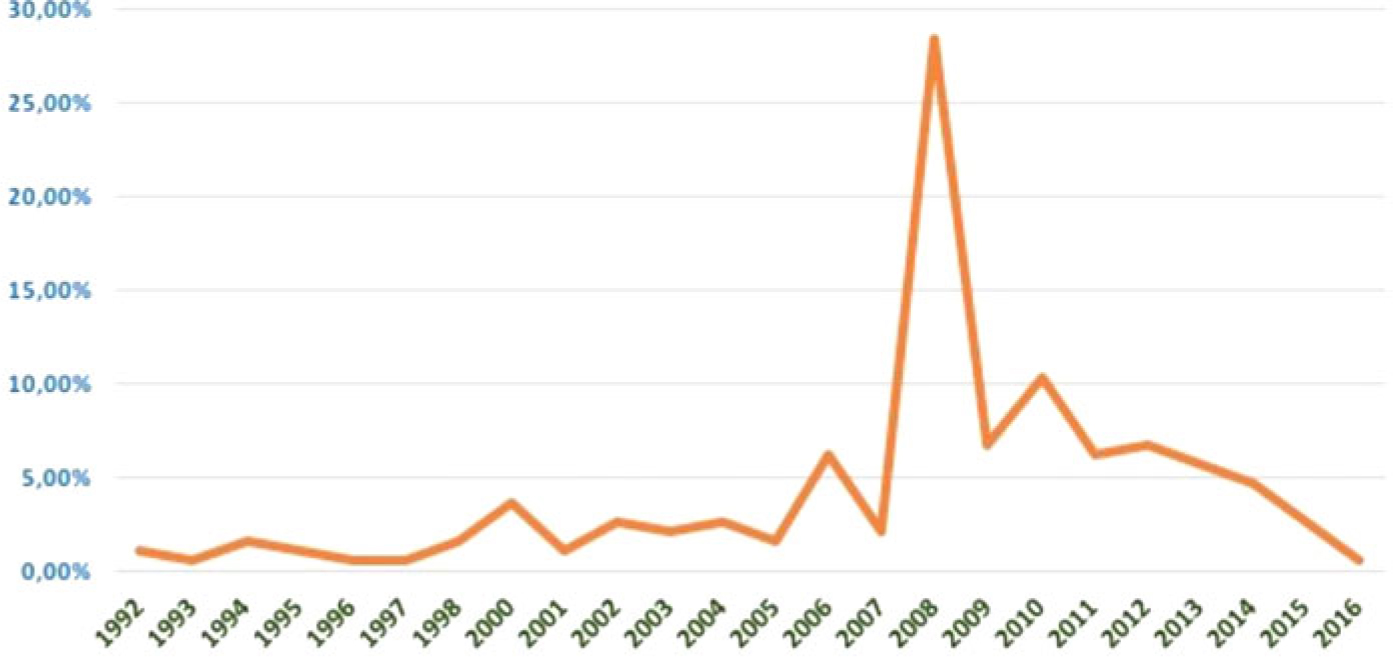

Year of publication. This shows: (1) The bigger latency period of the theory dissemination in Asia, considering the first contribution by an author from this continent was in 1992 (40 years after the first paper published by Moscovici in Reference Moscovici1952, before his opera prima, Reference Moscovici1961/Reference Moscovici1976; for a systematic meta-theoretical analysis of the two editions, see de Rosa, Reference de Rosa, Howarth, Kalampalikis and Castro2011), compared to the earliest propagation in Europe (de Rosa, Reference de Rosa and de Rosa2013a, Reference de Rosa and de Rosa2013b) and in other continents – in particular, in Latin America (de Rosa, Reference de Rosa, Lo Monaco, Delouvée and Rateaux2016a; Reference de Rosa and Khosrow-Pour2017; de Rosa, Forte, & Dryjanska, Reference de Rosa, Forte, Dryjanska, Batista Moura, Silva Arruda and Rangel Tura2015). (2) The exponential dissemination effect in correspondence from the 9th International Conference on Social Representation (ICSR) organised in 2008 at Bali, Indonesia, the first in Asia among the biannual series of ICSRs, consistent with the results of empirical studies on the role played by previous editions of the ICSRs (de Rosa & d’Ambrosio, Reference de Rosa and d’Ambrosio2008).

Other fundamental factors for the scientific dissemination of SRT include:

(1) Asian early-stage researchers who moved to Europe for their doctorates, working under the supervision of the theory founder or other leading scientists in SRT, especially at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS) in Paris, France, the London School of Economics in the UK, and at the European/International Joint PhD in Social Representations and Communication (SR&C) Research Centre and Multimedia Lab, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy (see de Rosa, Reference de Rosa, Lo Monaco, Delouvée and Rateaux2016a), followed by their return to Asia.

(2) The translation of some of Moscovici’s books in different domains of his scientific interests, including the relation between the man-nature and the ecologist movement. (De la Nature, Reference Moscovici2002, translated into Chinese in 2005); Social Representations (Reference Moscovici and Duveen2000, translated into Chinese in 2009 in simplified version and in 2010 by Jian Guan as an integral version), and Social Influence and Social Change (Reference Moscovici1976, translated into Korean in 2010).

(3) The scientific and institutional networking activities during the training events organised by the European/International Joint PhD in SR&C; the SoReCom “A.S.de Rosa”@-library and the Academic Social Networking in the dissemination of the Social Representations Literature (de Rosa, Bocci, Dryjanska, & Borrelli, Reference de Rosa, Bocci, Dryjanska and Borrelli2016c; de Rosa et al., Reference de Rosa, Dryjanska and Bocci2017a, Reference de Rosa, Dryjanska, Bocci and Khosrow-Pour2017b, Reference de Rosa, Dryjanska, Bocci and Khosrow-Pour2017c). It should be also noted that the decrease of frequencies shown in Figure 2 that apparently sanctions the scientific productivity for the period 2014–2016 also reflects the operational process for the retrieval of the sources; therefore, this decreased frequency should be taken as a provisional result (as confirmed by experience of data retrieval/accumulation in other geocultural areas).

(4) The “Journal’s name”, reflecting the wide diversified choice of journals (total F = 72), that includes but is not restricted to Asian journals for the publication of the 107 papers considered here. Most of the papers in our sample were published in Papers on Social Representations (12.15%), a journal dedicated to SRT, published by the Austrian Linz University until 2009 and later by the London School of Economics; 4.67% of the papers were issued in the Asian Journal of Social Psychology (N = 5), focused on promoting social psychological research in the Asia-Pacific region and published by the Asian Association of Social Psychology and Beijing Normal University. Each of the following journals were chosen by 2.80% of the authors in our sample: Culture & Psychology (focused on multidisciplinary psychology, and enriched by editors and authors from both the US and Europe), the European Journal of Social Psychology (the official journal of the European Association of Social Psychology, open to many affiliated members especially from the US and Australia), Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology (edited by Chinese universities, focused on issues related to the indigenous and minority populations and the developing world, with an emphasis on the regions of Oceania, Australasia, East Asia, the Western Seaboard of the Americas, the Hawaiian Islands and Pacific Island Nations), and Youth Studies (a journal published in Hong Kong dedicated to research on youth policies, with a stated mission of improving legislation for youth). In the full list of 72 journals related to the selected corpus of bibliographic resources for this study (see Table S1 in Supplementary Materials) we identify the network of professional collaborations with Europe and North America, as well as a focus on local contexts in the Pacific region (see de Rosa, Reference de Rosa, Lo Monaco, Delouvée and Rateaux2016a, Reference de Rosa and Khosrow-Pour2017). From a disciplinary point of view, we find that the thematic areas range from theoretical issues (social psychology, SRT, cultural psychology) to more applied ones (e.g. youth studies, indigenous and minority populations issues), in line with the interdisciplinary character of SRT documented by Rateau et al., Reference Rateau, Moliner, Guimelli, Abric, Van Lange, Kruglanski and Higgins2011, and preferably conceptualized as “supra-disciplinary” by de Rosa (Reference de Rosa and de Rosa2013a; Reference de Rosa2014; see Table S1 in supplementary information.)

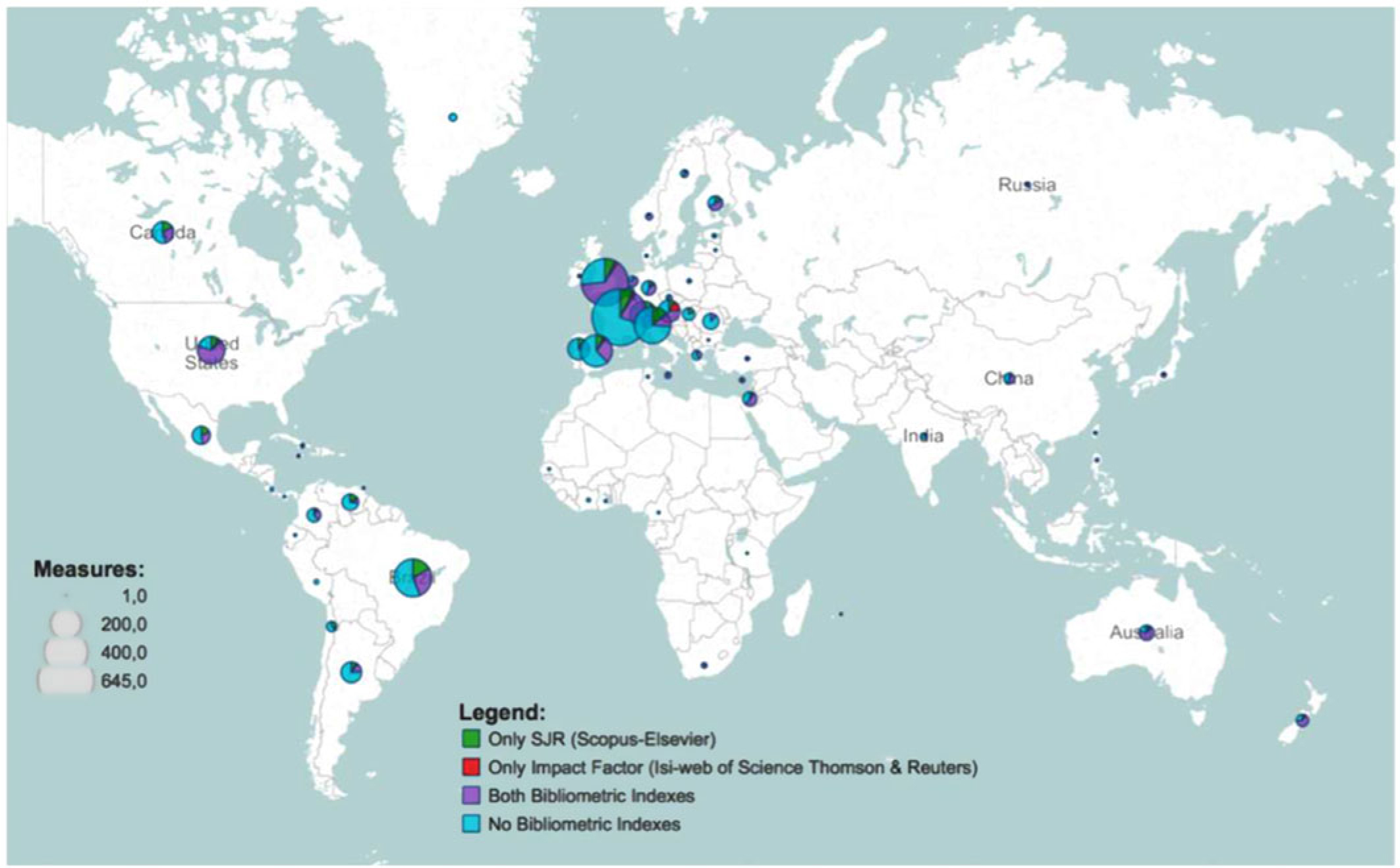

(5) The inclusion/exclusion of the 107 articles in journals indexed in the bibliometric databases Thompson and Reuter Web of Science by impact factor (IF) and Scopus-SCImago (SJR), again show a slight majority of publications in non-indexed journals, especially for IF (see Table 2). However, comparing the results from Asia to trends emerging from the overall worldwide production on SRT visualized by the geomapping performed by Tableau (see Figure 3), together with North America and Oceania, Asia is one of the prominent continents for articles published in indexed journals compared to Europe (where the theory was initially generated in the 60’s and largely spread in the 80’s) and to Latin America (where the theory has been largely disseminated well before it was in Asia), thus reflecting the increasing pressure for publishing in indexed journals in more recent decades, and the openness to the SRT of three important journals (Asian Journal in Social Psychology, the Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology and Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research) among the top indexed journals in both bibliometric databases (see Table 3).

Figure 2. Percentage distribution of 194 bibliographic sources from Asia by “Year of Publication”.

Figure 3. Geomapping the frequency distribution of 3,234 worldwide articles by country of the first author’s institutional affiliation and by indexation in Web of Science and Scopus (de Rosa, Reference de Rosa2015b, Reference de Rosa, Lo Monaco, Delouvée and Rateaux2016a).

Table 2. Distribution of articles based on bibliometric databases indexation

Table 3. Journals indexed in both bibliometric databases ranked by impact factor

The influence of other factors should be also considered, including: (a) scientists’ individual preferences to publish articles rather than book chapters or books, also taking into account the relation with their academic roles and generational levels; (b) their preferred publishing strategies (e.g. as single authors or in teams of collaborating co-authors); (c) the preferred language in which to publish (often English); (d) the internationalization of the scientists’ careers (e.g. international collaboration, international project collaboration or leadership, study period abroad); (e) their preferred approach: experimental/quantitative vs. qualitative, and to what extent); and (f) the pressure of several indicators of their scientific productivity and institutional recognition (e.g. research grants, awards, leadership roles, appointment to international committees, editorial responsibilities - see de Rosa, Reference de Rosa2015b; Reference de Rosa, Lo Monaco, Delouvée and Rateaux2016a; de Rosa et al., Reference de Rosa, Dryjanska, Bocci and Khosrow-Pour2017b).

Looking at the descriptive profile based on the following sections of the Grid, the results show that the majority of our publications were empirical (68%), followed by theoretical papers (31%) and 1% thematic reviews.

The “reference to SRT” was specific in most cases (84.02%), with an evident focus on the functions of SRs (68%), specifically orientation and control of social reality (58.24%) and guide of behavior and intergroup relations (42.3%), followed by the transformation of social representations (SRs), present in 38.1% of our papers, genesis-related aspects (29.4%), process-related data (28.9%), and how SRs are transmitted (24.2%). The structure of SRs was only mentioned in 13.9% of our publications, and we found very few papers employing specific paradigmatic approaches as defined by de Rosa (Reference de Rosa and de Rosa2013b): 6.2% of them were conducted within the “anthropological and ethnographic” paradigmatic approach to SRT, followed by the “dialogical, conversational and narrative” paradigmatic approach (4.1%), with only 3.6% of them included in the “structural” approach to SRT, and, respectively, 2.1% on the “socio-dynamic” approach. The focus on the anthropological and ethnographic paradigmatic approach to SRT as opposed to the other paradigmatic frameworks, together with “cultural knowledge” as the most referenced construct and “culture” as a main thematic area, may be due to the fact that this paradigmatic approach studies people’s knowledge in context, which was prescribed for the Asian social psychology in its entirety (e.g. J.H. Liu & Ng, Reference Liu and Ng2007; Ward, Reference Ward2007).

The “most referenced constructs and concepts” in our sample were: “cultural knowledge” (63.92%), “social processes” (53.09%), “context” and “practice” (each found in 50.52% of the total number of papers analyzed). Concerning other theories and paradigmatic approaches, “social identity theories” was mentioned most often, in 25.26% of the publications, distantly followed by “social cognition theories” (13.92%) and “social constructionism” (10.82%).

Thematically, the most popular area of study was “identity” (18.6%), followed by “politics-ideology” (16.5%), “SRT, meta-theory and methodological issues” (13.4%), and “culture” (11.9%).

SRT lends itself well to the study of cultural-specific, indigenous phenomena occurring in this area. Moreover, the focus on “culture” as a thematic area was also found by Haslam and Kashima (Reference Haslam and Kashima2010) in the bibliometric analysis of papers from Asian social psychology in general.

Investigating the “methodological profile”, systematically detected through the meta-theoretical analysis of the empirical papers (N = 132) from Asia, we found that the researches were mainly conducted in “urban” areas (28.8%), followed by “rural” areas (6.8%), “islands” (2.3%) and “metropolitan areas” (0.8%). The most popular research design was “descriptive” (77.3%), followed by “quasi-experimental” (9.8%) and “experimental” (2.3%) with the most research conducted in a “laboratory” setting (54.5%) and “comparatively between groups” (36.4%). The preferred sampling technique was “convenience” (78%), while the size of the samples mainly exceeded 100 participants (52.3%), who were in most studies “subject without social positioning” (44.7%). “Open instruments” were employed in 50.8% of the studies, with semi-directive interviews and free interviews having been used in 14.4% each, followed by word association techniques (11.4%) and open-ended questionnaires (9.8%). “Structured instruments” were employed in 43.9% of the studies (questionnaires/structured instruments in 42.4%, and scales in 12.9%), whereas “observant techniques” were employed in 9.1% of the cases, and “figurative-graphic techniques” in 2.3% of the papers. The data analysis techniques were mostly “quantitative” (42.4%), followed by “qualitative” (38.6%). According to the bibliometric analysis conducted by Haslam and Kashima (Reference Haslam and Kashima2010), the Asian context may be marked by a positivist and quantitative empirical trend due to the fact that most recent research comes from developing countries (e.g. mainland China), where science and societal progress are construed in a modernist framework (a top-down approach, implemented in all public areas) as opposed to a postmodern and postindustrial one (J.H. Liu & Ng, Reference Liu and Ng2007). As a consequence, the vast majority of Asian empirical papers in social psychology tend to merely describe the phenomena of high social interest rather than theorize them, which makes them resemble more closely the mainstream and applied social psychology, rather than creating psychological theories departing from the empirical analysis of local experience (Haslam & Kashima, Reference Haslam and Kashima2010; J.H. Liu & Ng, Reference Liu and Ng2007).

Crossing meta-data and data – multiple correspondence analysis and hierarchical clustering on principal components analyses

How SRT is appropriated conceptually and in relation to other theories, as well as further insight into (1) the theory’s spatial and temporal trajectory beyond the descriptive profile, and (2) the main thematic areas in which SRT is employed in Asia. We analyzed the data obtained by applying the Grid for Meta-Theoretical Analysis on all 194 publications through hierarchical clustering on principal component (HCPC) analyses and a clustering algorithm that combines Ward’s hierarchical clustering (HC) with k-means (for more detail, see Husson, Lê, & Pagès, Reference Husson, Lê and Pagès2010).

The classical bibliographic categories included in the first part of the Grid (e.g. resource type, author, first author institutional affiliation, country, year of publication by decade, language, empirical/theoretical/thematic review type of paper) were used as “illustrative” variables, while the categories and modalities included in the following sections of the Grid specifically related to the meta-theoretical analysis (references to SRT-related concepts and references to other concepts, theories and paradigmatic approaches, thematic areas, paradigmatic approaches, typology of SRs – hegemonic, emancipated, polemic) were used as “active” variables in the preprocessing step, which consists of running a multiple correspondence analysis (MCA).

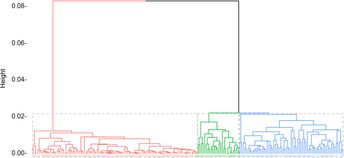

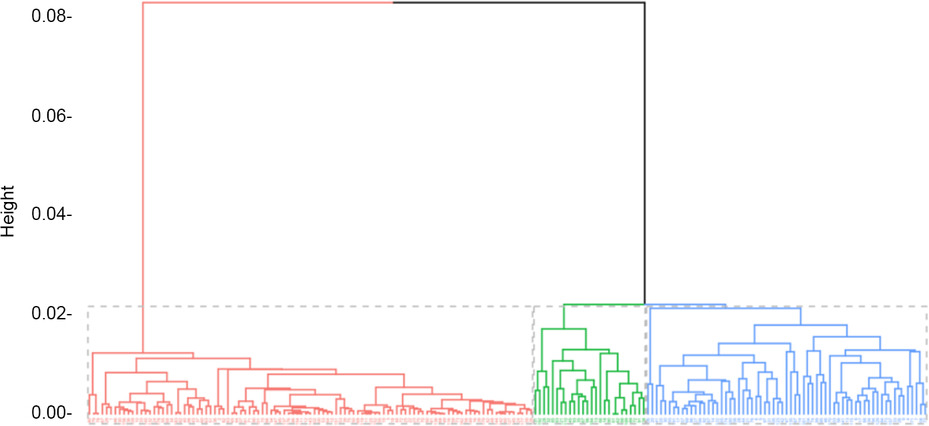

Ward’s HC was applied to the MCA results (the first 61 dimensions, which explains 90% of the inertia) to determine the number of clusters to be later consolidated with the k-means algorithm. The results of the HC show that the data is best divided into three clusters of publications, which are then consolidated to engender the final solution (see Figure 4). Chi-square tests of association between the variables presented above and the three-cluster solution reveal the modalities of the variables that are significantly associated with each cluster, as well as whether the association is positive or negative.

Figure 4. Hierarchical clustering – initial partitioning for the HCPC on all 194 publications from Asia.

The clustering solution reveals that there may be three manners in which SRT is used by authors in Asia. The first one, represented by the publications in Cluster 1, concentrates 55.15% of the publications from the initial corpus and comprises almost all the conference presentations (95.18%) and most of the papers (90.32%) that reference SRT in a generic way – that is, without citing specific SRT constructs, processes, or functions – which is quite common for conference presentations rather than for journal articles, according to results based on meta-theoretical analyses of corpus from other geocultural contexts, also due to the effects of editorial formatting. All the Indonesian publications may be found in this cluster (100%), and more than a half of these items were issued between 2002–2011 (63.16%). Thematically, this cluster comprises most of the publications on gender and family roles (84.62%), although these publications make up merely 10.28% of the total number of items in Cluster 1. Regarding the language of publication, Cluster 1 is significantly associated with English (89.72% of all its items). Moreover, we found significant negative associations with references to SRT-related concepts as well as with concepts, constructs and approaches pertaining to other theories. Thus, Cluster 1 shows that in the Asian geocultural context (entirely represented by Indonesian publications), SRT is often employed instrumentally for the study of socially relevant phenomena, with less focus on theoretical development.

Cluster 2 concentrates 17.01% of all the publications in our corpus and is mainly made up of articles published in journals (90.91% of the items in this cluster). More than a half of the publications here are theoretical (51.52%) and all of them treat SRT specifically (100%). They were mainly first authored by Chinese researchers (66.67% of all publications in this cluster), published in Chinese (54.56%) and issued very recently, from 2012 up to 2016. This line of research is focused on studying the processes through which SRs are formed (both “anchoring” and “objectification”), as well as their functions (“familiarization with the unfamiliar”, “facilitating communication”, “orientation and control of social reality”), their genesis (“socio-genesis”), and the way they are transmitted (via “communication”). Regarding other concepts and theories, we find significant associations between individual representations, common sense, value and collective representations, and social cognition theories, discursive psychology and social constructionism. Thus, given the theoretical orientation of this cluster and the fact that it comprises 50% of the papers on the topic of SRT, meta-theory and methodological issues, we may conclude that recently, mainly in China, researchers have been closely focused on the conceptualization of SRT (mainly the way it is formed through processes and socio-genesis) and on a meta-theoretical debate, in the sense that SRT was compared to the other approaches in social psychology with which previous research has found epistemological ties (e.g. for social cognition theories: Augoustinos & Innes, Reference Augoustinos and Innes1990; de Rosa, Reference de Rosa, von Cranach, Doise and Mugny1992; for discursive psychology: de Rosa, Reference de Rosa2006; Potter & Edwards, Reference Potter and Edwards1999; for social constructionism: Moscovici, Reference Moscovici1988).

Cluster 3 represents 27.84% of our sample and is mostly made up of articles (92.59%) presenting empirical research (81.48%), specifically referencing SRT (94.44%), first authored by Israeli researchers (40.82%) from 2012 to 2016. This research direction references the functions of SRs (“social identity related functions”, as a “guide for behavior and intergroup relations”, facilitating “orientation and control of social reality”), their genesis (“micro-genesis”), their transformation (via “social influence through interaction”, via “social identity”, via “knowledge”, via “communication”, via “social changes”) and their transmission (via “social identification”).

Regarding other constructs and theories, we have significant associations between “self”, “behavior”, “change”, “motivation”, “attribution”, “context” and sociological, philosophical and anthropological approaches, and between social influence and attribution theories. The research is mainly conducted inspired by the anthropological and ethnographic paradigmatic approach to SRT (58.33%). Thus, the research direction in Cluster 3 is of a more applied nature, as reflected in the type of theories with which SRT is presented in conjunction. As such, compared to Cluster 2, which was significantly associated with theories that share epistemological ties with SRT, we find here theoretical frameworks that more easily lend themselves to instrumental empirical research of social dynamic phenomena and social objects (e.g. sociological approach, social influence theories, attribution theories, social interaction theories). An additional difference between Clusters 2 and 3 is that while Cluster 2 is associated with theoretical aspects of SRT, highlighting how a SR is formed (e.g. via “processes”), Cluster 3 is more focused on the impact of SRs on social life – that is, people and groups’ identity (“social identity related functions”, “transformation via social identity”, “transmission via social identification”), and group dynamics (“micro-genesis”, as a “guide for behaviour and intergroup relations”, and as “transformation via social influence through interaction”).

In summary, our findings reveal a temporal shift from a more generic and applied tradition of research on SRT in 2002–2011 (also noted by de Rosa in Reference de Rosa and de Rosa2013b) to a more theoretically oriented empirical research trend starting from 2011 (evinced in Cluster 3) and paralleled temporally by a distinct research line that deals with meta-theoretical aspects, and hence, a recent preoccupation with theoretical developments. Spatially, these research trends are associated with the scientific production in Indonesia (Cluster 1), China (Cluster 2) and Israel (Cluster 3), which is partially in line with Haslam and Kashima’s (Reference Haslam and Kashima2010) findings, according to which there is a preponderance of Chinese scientific literature in Asian social psychology. Regarding the conceptual appropriation of SRT, apart from the generic trend specific to older publications, our results show that the theoretical references to SRT cover all the categories proposed by de Rosa in her Grid for Meta-Theoretical Analysis, as well as the vast majority of concepts and constructs pertaining to other theories.

Empirical publications on SRT from different Asian geocultural contexts and in different decades articulate theoretical aspects with methodological options in various thematic areas. For the purpose of addressing our research question focused on how SRT was employed empirically in the Asian geocultural context, as well as gain further insight into how the theoretical aspects articulate with the methodology choices in certain thematic areas, we employed the main theoretical categories, along with the main thematic areas and data about methodology from the Grid for Meta-Theoretical Analysis as variables in another HCPC analysis conducted only on the 132 “empirical” publications in our sample. Results revealed a three-cluster solution (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Hierarchical clustering – initial partitioning for the HCPC of the 132 empirical publications from Asia.

The MCA, employed as a preprocessing step of the data, was performed on the list of variables presented above, to which categories related to methodological profile were added (e.g. type of methods, data analysis techniques). The HCPC subsequently took into account the first 36 dimensions from the MCA (90% of the inertia).

Cluster 1 concentrates 42.42% of our sample, and presents empirical research conducted between 1992–2001 (81.25% of the empirical items issued in this timeframe are in Cluster 1), mainly by Israeli first authors (65% of all the publications here), who employed mostly structured instruments (questionnaires or structured interviews, scales), as 82.48% of all the papers using these methods are in Cluster 1, and quantitative data-analysis techniques (descriptive statistics, bivariate and multivariate techniques), as 83.93% of all the papers using these statistical tests are in Cluster 1. The research was carried out in laboratory settings on convenience samples and was of an intergroup and cross-national nature, with a quasi-experimental research design.

Cluster 2 concentrates 17.42% of our corpus, and presents papers that refer to the theory in a more generic way (42.11% of all the papers addressing SRT without any reference to specific constructs are here) issued as conference presentations (73.91% of all the items in Cluster 2), mainly first authored by Indonesian researchers (60% of the total number of papers) between 2002–2011 (21.74%), with no statistically significant associations for any theoretical, thematic or methodological aspects.

Cluster 3 concentrates 40.15%, and presents empirical research conducted by Indian first authors (85.71%) and published in journal articles in 71.70% of the cases, within the anthropological and paradigmatic approach to SRT (81.82%). The reference to SRT was specific in 96.23% of the elements of the cluster, focused on SRs’ genesis-related concepts, and their functions, transmission and transformation, mainly on identity and deviance as thematic areas. Methodologically, Cluster 3 group’s empirical publications employed qualitative data analysis techniques (content analysis, thematic analysis) – 88.24% of the publications employing this type of statistical analysis are here), open instruments (free and semi-directive interviews) – 62.68% of the publications employing this type of method are here, and observation techniques – 75% of the publications employing this type of method can be found in Cluster 3, in descriptive research designs, longitudinal studies conducted in field settings on convenience samples.

Therefore, we may conclude that three different lines of empirical research are delineated by each of the clusters, mainly differentiated through the methodology employed, which was found to be articulated with the use of SRT only for the last two clusters. Thus, when SRT was employed generically, we do not have any significant associations with a certain type of methodology or data analysis technique, while when it was employed specifically (Cluster 3), the methodology was more anthropologically oriented, and more qualitatively inclined. Cluster 1 represents the “oldest” empirical research line in Asia, conducted more in the spirit proposed by the mainstream tradition in social psychology, which reflects how the latter penetrated the Asian area, via North-American influences and standards (Kruglanski & Stroebe, Reference Kruglanski and Stroebe2010). It opposes Cluster 3, as it does not contain any publication employing observant techniques (0.00%), and only 7.14% of the publications employed qualitative data analysis techniques, while 35.71% of the papers used open instruments. On the other hand, Cluster 3 only comprises 13.21% of items employing quantitative data analysis techniques and, coincidentally, the same percentage of items employing structured instruments (13.21%). If we take into account the fact that many empirical papers employ mixed methods and consequently mixed data-analysis techniques, we may notice that the opposition between Clusters 1 and 3 reflects the debate between the use of quantitative and qualitative in SRT (see Garnier, Reference Garnier2015; Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Duveen, Farr, Jovchelovitch, Lorenzi-Cioldi, Markova and Rose1999) and, combined with the temporal trajectory, our findings reveal the same trend noticed by de Rosa’s meta-theoretical analysis from 2013b on a global sample of SRT papers, which revealed a trend toward the integration of quantitative and qualitative methodologies. This may point towards the fact that the evolution of SRT in the Asian context shares similarities with its development in other geocultural contexts and can be an indicator that the scientific community inspired by SRT is more ready to welcome a more integrative epistemological and methodological vision, as expressed by the “modelling approach”, to overcome the fragmented subcircle of diverse schools of thought and the polytheism of methods and move even beyond the traditional multimethod approach (de Rosa, Reference de Rosa1990, Reference de Rosa and de Rosa2013a, Reference de Rosa and de Rosa2013b, Reference de Rosa2014; de Rosa, Bocci, Dryjanska, & Latini, Reference de Rosa, Bocci, Dryjanska and Latini2016d).

Conclusions

The objective of our research was in line with one of the larger questions of the project from which it originates (“Is it possible that the same theory is differently referred to when used by researchers adopting different approaches or working in different cultural scenarios? If so, what does this mean?”; de Rosa, Reference de Rosa and de Rosa2013b, p. 95), thus tracing the development of a European theory across time, space and disciplines, to identify whether the theory has undergone conceptual and/or methodological transformations while transcending to other cultural areas over time.

Therefore, we first looked at the pre-existent, socio-cultural conditions in which SRT was adopted in the Asian geocultural area, so that we may get a glimpse into the reasons why they have chosen to adopt SRT according to their cultural academic agendas. Thereupon, a review of the literature on this topic reveals that the researchers from the Asian geocultural area are interested in creating an original Asian social psychology based on their context-specific cultural and social phenomena; hence, they favor a basis in indigenous psychology as opposed to one in a social psychology created in and for other cultural areas (J.H. Liu & Ng, Reference Liu and Ng2007). This type of social psychology should also have a practical orientation, in the sense that it should promote ways of dealing with contemporary social issues (Atsumi, Reference Atsumi2007). SRT, albeit created in the European space, is versatile and highly flexible, and designed specifically for capturing culture-sensitive lay knowledge, which explains why the Asian social psychologists employ it in order to attain their goal of the creation of an original Asian social psychology (J.H. Liu & Sibley, Reference Liu, Sibley, Montiel and Noor2009). Therefore, the current situation of SRT in Asia, as revealed by our findings, has to take into consideration these two aspects: the striving for a unique Asian social psychology and the social utility and applicability of empirical research. In doing so, we may understand the weak focus on theoretical developments (J. Liu, Reference Liu, Permanadeli, Jodelet and Sugiman2008) found in our HCPC analyses (especially in conference presentations, compared with other types of contributions) and the over-abundance of diverse thematic foci evinced by our textual analysis of abstracts and keywords, in line with Chiu’s (Reference Chiu2007) listing of pressing social issues in this geocultural area. Regarding the latter, the lack of homogeneity of Asia reflected in the controversies surrounding the territories and cultures considered as defining for an Asian identity, detailed in our introduction, is also apparent in our textual analysis findings, as the data corpus was divided into five clusters, each significantly associated with diverse countries (in particular, China, India and Turkey; Taiwan, Lebanon and Japan; the Philippines; Indonesia; Israel). Our results reflect the fact that SRT is indeed employed for a wide variety of objects of study, mainly focused on the socio-cultural issues specific to this geocultural area.

All in all, the trends highlighted by our findings reveal great potentiality for further dissemination and development of SRT in Asia, if we take into account that no reference to SRT can be retrieved in any of the empirical studies that apply diverse social psychological theories and approaches, to understand and address a wide range of social concerns in Asian societies. This result is even more impressive considering that most of these studies are mainly derivative of Western social psychological paradigms, with the exception of a couple of studies that adopt emic indigenous approaches. Hence, our results support the potentiality for wider reference and appreciation of SRT among social psychologists in Asia, as it fits well with both the holistic style of thinking characteristic of this particular geocultural space (J. Liu, Reference Liu, Permanadeli, Jodelet and Sugiman2008), as well as with its societal concerns, which are more and more argued to be the truly valuable scope of social psychology (J.H. Liu & Ng, Reference Liu and Ng2007; Ward, Reference Ward2007).

Regarding the limitations of our research, we refer to the issue signalled in our introduction regarding the geocultural definition of “Asia”, given that the Asian space is very vast and multilingual, which may have also led to our sample potentially not being representative for all the nations in this continent. Although the “A.S. de Rosa”@-library is the most comprehensive specialized repertory in social representation (de Rosa, Reference de Rosa2015a), also compared to three academic social networks (ASNs) all together (Academia.edu; ResearchGate and Mendeley) have empirically verified that only 31% of publications filed in the specialised @-library were present in at least one of the three ASNs (de Rosa et al., 2016c); the sources analyzed in this contribution (extracted up to March 2016) are not exhaustive of current research findings. Also, many of our conference presentations were available in abstract form only, which may have biased our results regarding the generic employment of the theory. Due to the nature of this study, our research was exploratory, not confirmatory in nature, but – inspired by the Moscovici’s vision that research in social psychology is for “improving, not for proving” (de Rosa, Reference de Rosa2003) – we are confident that it is quite unique in its meta-theoretical approach and methodology used, thus providing a basis for further studies on the continuously growing literature.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/prp.2019.1

Author ORCIDs

Annamaria de Rosa 0000-0002-2945-6103

Acknowledgments and Funding

This paper was part of a larger European Commission-funded project, ITN-People MSCA-IDP 2013, no. 6072799 http://www.europhd.net/sorecom-joint-idp and implied the collaboration between the project leader Annamaria de Rosa and Mihaela-Alexandra Gherman, one of the 13 early-stage researchers recruited on this contract; http://www.europhd.net/sorecom-joint-idp.

Financial support

None.