Starting in late 2008, an economic crisis hit the world's global economy, causing a severe social, political and economic impact, including loss of jobs, income, savings and homes. The United Nations (2009) reported a range of impacts and concerns, including rapid increases in unemployment, poverty, hunger, deceleration of growth, economic contraction, growing budget deficits, reduced ability to maintain social safety nets and provide other social services (e.g., health and education), collapse of housing markets, and declining remittances to developing countries. The International Labour Organisation (2010) estimated that global unemployment hit 210 million in mid-2010, just over 30 million more than the pre-crisis 2007 levels.

Personal Impacts of the Global Economic Situation

During the height of the global crisis, the economy was the top story for the media (Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, 2009). But how much did the economy actually impact people who had not lost their job? People internalise the uncertainty, and change their behaviour accordingly. An OECD report noted that household saving was increasing rapidly in the face of rising unemployment and perceived loss of wealth (OECD, 2009). When unemployment is rising, job insecurity becomes a major issue. Job insecurity is defined as ‘a perceived powerlessness to maintain desired continuity in a threatened job situation’ (Greenhalgh & Rosenblatt, Reference Greenhalgh and Rosenblatt1984, p. 438). As organisations downsize and lay off workers, even those individuals who survive the lay-offs may experience feelings of job insecurity. Similarly, Aldwin and Revenson (Reference Aldwin and Revenson1986) conducted a large-scale study that found economic stress adversely affected psychological health, even controlling for mental health condition. According to Levy and Sidel (Reference Levy and Sidel2009), individuals felt personally affected by the economic crisis, and many were stressed, depressed, and exhibited a loss of self-esteem. Severe recessions create uncertainty of future outcomes, which leads to stress even for those who maintain their employment. Job insecurity can result in stress, anxiety, and even anger for employees (Greenglass & Burke, Reference Greenglass and Burke2001; Unal-Karaquven, Reference Unal-Karaquven2009).

The current study focuses on the situation of workers in New Zealand during the economic crisis. New Zealand has the second highest rate of university-educated citizens living abroad of any OECD country, but this is compensated by the influx of highly skilled migrants who now make up more than 20% of the New Zealand workforce (Dumont & Lemaitre, Reference Dumont and Lemaitre2004; Statistics New Zealand, 2006). Even before the recession, migrants were at a disadvantage compared to New Zealand-born workers, in terms of wages, employment rates and occupational rank, with university-qualified migrants taking about 10 years to reach parity with New Zealand-born workers (Stillman & Mare, Reference Stillman and Mare2009). The current recession was relatively mild in New Zealand, with unemployment rates peaking at nearly 7% in the December 2009 quarter (Statistics New Zealand, 2010). However, this average figure masks major disparities in how the recession has impacted migrants, with 17% unemployment of Middle Eastern/Latin American/African ethnic groups and 14% unemployment of Pacific Peoples, while the majority European group has only 4.6% unemployment. This issue is by no means unique to New Zealand, as there are similar labour market penalties for immigrants in Europe (Reyneri & Fullin, Reference Reyneri and Fullin2011). With these differing labour market experiences, it is expected that New Zealand-born and migrant workers will have different perceptions about the impacts of the economic downturn.

International Migration

New Zealand is shared between tangata whenua, the Māori, and later arrivals, coming primarily from the British Isles from the late 18th century onwards. Since those early days, the range of countries that send migrants to New Zealand has expanded dramatically. The Immigration Act of 1987 provided a path for skilled migrants from any country, opening the doors for sharp increases in migration from China, India, and South Africa (Department of Labour, 2011; Shorland, Reference Shorland2006).

Reasons for this migration are sometimes categorised by push-pull factors that repel people from their country of origin (war, crime, lack of employment opportunities) or attract them to a destination (environment, safety, economic opportunities). Differentiating between ‘macro’ and ‘micro’ factors offers another approach for understanding motivation (Boyd, Reference Boyd1989). The macro approach looks at the environmental reason (wage differentials, government policies, physical environment) why individuals leave their country of origin and migrate elsewhere. The micro approach focuses on personally relevant reasons why the migrant leaves (lifestyle, family, career gains). Both macro and micro approaches are strongly interlinked, as decisions to migrate are complex and highly individual. Previous studies have found reasons for migration to New Zealand go beyond potential wages, instead focusing on lifestyle, environment and safety (Masgoret, Merwood, & Tausi, Reference Masgoret, Merwood and Tausi2009; Tabor & Milfont, Reference Tabor and Milfont2011). The reasons migrants leave New Zealand have very seldom been studied (Burgelt, Morgan, & Pernice, Reference Burgelt, Morgan and Pernice2008), but European research into return or onward migration has focused on family, economic, visa/citizenship barriers (Brugha, McGee, & Humphries, Reference Brugha, McGee and Humphries2009; Dustmann & Weiss, Reference Dustmann and Weiss2007; Fuchs-Schündeln & Schündeln, Reference Fuchs-Schündeln and Schündeln2009).

Because of New Zealand's dependence on foreign-born labour, return and onward migration of these immigrants is a major concern (McLoed, Henderson, & Bryant, 2010). There is a popular impression of New Zealand as ‘the land of the long white transit lounge’, with migrants only staying in New Zealand long enough to allow them access to Australia (Tyler, Reference Tyler2008). Australia also considers this ‘back door’ migration a problem (Hoadley, Reference Hoadley and Catley2002). It is true that naturalised citizens are somewhat over represented in permanent and long-term arrivals in Australia, at about 36% compared to 17% of the total population (Sanderson, Reference Sanderson2009).

Beginning in the 1960s, waves of trans-Tasman migration have seen ever-increasing number of New Zealanders also leave for Australia (Carmichael, Reference Carmichael1993). In the year to June 2012, a record number of New Zealand citizens left for Australia — more than 48,000 — and an additional 5,100 non-New Zealand citizens also left for Australia (Department of Labour, 2012). This high rate of departure contributed to the net loss of migrants that New Zealand experienced in the past year. McLeod, Henderson, and Bryant (Reference McLoed, Henderson and Bryant2010) found that migrants to New Zealand with postgraduate qualifications were more likely to leave, as were migrants under age 30. The reasons behind them leaving were not explored in that study, but international findings have linked a number of factors, including frustration with economic opportunities (Pinger, Reference Pinger2010). Indeed, Brosnan and Poot (Reference Brosnan and Poot1987) analysed data over a 35-year period and found that trans-Tasman migration is highly sensitive to employment opportunities.

Because economics underlie theories of international migration (Boyle, Reference Boyle, Rob and Nigel2009), major changes in the global economic situation would be expected to heavily influence migration behaviour. Internationally, migration has been profoundly affected by the crisis, with the growth of immigration in Western Europe and the United States coming to a standstill (Papademetriou, Sumption, & Terrazas, Reference Papademetriou, Sumption and Terrazas2011; ‘The people crunch’, 2009). Bastia (Reference Bastia2011) found that family and health reasons were dominant in the return migration decision of Bolivian and Argentinean migrants to Spain even during the present economic crisis, and that those who stayed were willing to make sacrifices on their pay and employment conditions to remain. Historically, Green and Winters (Reference Green and Winters2010) noted that though economic crises such as the Irish Potato Famine had a significant impact on migration, the general pattern over time is only a weak relationship between emigration and economic growth. Reasons for migration may not be changed by economic downturns, but the ability of potential migrants to act on those reasons may be severely hampered by factors such as declining house values, changes in currencies and perceptions of declining personal resources.

Although some research has examined the effects of the economic crisis on the overall New Zealand population, little research has been conducted on the different effects between individuals born in New Zealand and migrants. Therefore, this project aimed to ascertain answers to the research questions: (1) In what ways has the economic crisis affected workers? (2) Does the economic crisis influence individuals’ likelihood to leave New Zealand? (3) How do views on the economic crisis and migration differ between those born in New Zealand and migrants?

Methods

Participants

The present study included responses from 1,578 participants. A total of 837 females (53.2%) and 706 males completed the survey; 30 participants did not state their gender. Participants ranged in age from 16 to 72 years (overall M = 37.49, SD = 12.54). Of the 1,505 people who listed a country of birth, 1,153 were born in New Zealand (76.6%) and 352 participants were born overseas (23.3%). A total of 47 nations were represented, with the most common being the United Kingdom (30%), China (7.3%), Australia (7.1%), South Africa (6.8%), India (5.9%), the United States (5.9%), and Samoa (4.8%). Of those not born in New Zealand, the mean time they had lived in New Zealand was 14.63 years (SD = 14.96, range less than one year to 64 years). Thirty-five per cent of the sample held skilled migrant visas, and 2.2% were refugees; the remaining participants checked the ‘other’ box or did not answer the visa question. Fifty per cent held permanent residency in New Zealand and 35.7% had New Zealand citizenship. Overseas-born employees had worked for their organisation on average (M = 4.77, SD = 5.56) for slightly less time than New Zealand-born employees (M = 5.81, SD = 6.74). The ethnic makeup of the New Zealand-born sample was 733 NZ European/Pakeha (63.6%), 97 Māori (8.4%), 35 Pacific Islanders (.03%), 16 Asian (.01%), and 172 describing themselves as New Zealander or Kiwi. Most of the sample (86.8%) worked full-time.

Measures

Questions were included in a larger survey on work conditions in New Zealand. The last portions of the survey consisted of closed-ended and open-ended questions regarding demographic details and views on the economic crisis, as well as migration intentions. For the present study, the open-ended questions targeted the participant's view on the current economic environment (‘Has the economic crisis affected you and your work life? If yes, please describe’). Because of the way the question was worded, we considered no response a not affected answer. The second open-ended question asked the participant's intentions to leave New Zealand due to the economic situation (‘Has the current state of the economy made you more likely to stay in New Zealand/return to your country of origin/or go to another country; which and why?’). A related close-ended question, ‘How likely are you to stay in New Zealand if you lost your job?’, was answered with very likely, likely or not likely.

Procedure

The targeted population were New Zealand and overseas-born working individuals. In order to get the targeted samples, Victoria University of Wellington undergraduate students were asked to select one organisation and collect responses from employees in that organisation. The anonymous survey was handed out to all agreeable participants and was collected between April 2009 and April 2010. The sample included employees of 64 businesses in the Wellington region, from both the public and private sector. All surveys were conducted in English. Participants completed the survey voluntarily and respondents were assured that their responses would be anonymous. The School of Psychology Human Ethics Committee of Victoria University of Wellington provided ethical approval.

Data Analysis

A mixed method was utilised, capitalising on strengths in both approaches. First, the responses to the open-ended responses were evaluated using thematic analysis. Qualitative research design was deemed ideal for exploratory investigation of how the recession has affected employees, as it allows more room for the participant to express their original ideas than does a quantitative approach. Thematic analysis is a qualitative method to find and report patterns or themes within data, using an inductive ‘data-driven’ approach (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). Each theme captures something important about the data in relation to the research question, and represents a level of patterned response or meaning within the data set. Finally, the questions on migration intention were examined using logistic regression to ascertain if there were significant differences between how migrants and New Zealanders responded, while controlling for age, gender and organisation.

Results

Concerns

In response to the first open-ended question (‘Has the economic crisis affected you and your work life? If yes, please describe’), 28.2% of the New Zealand-born and 28.7% of overseas-born reported being affected in some way by the economic crisis. Though many respondents gave a simple yes or no (and very often ‘not yet’ was the response), 365 participants described the ways in which the crisis had affected them. These descriptions were then further analysed. We identified five themes associated with individuals’ life and work environments during the current economic crisis: salary, workload, job security, budget/cut-backs, and job opportunity.

Salary

An important way that participants believed that the recession affected them was financially. Fifty-seven respondents said that their salaries would not increase (24% New Zealand-born and 19% overseas-born). Many feared that organisations were not going to increase their salary, as they had been accustomed to on a yearly basis. One respondent stated ‘no chance of pay increase’, and another respondent stated that there were ‘salary freezes for all management’. In addition, a few responses also specified that there were to be no bonuses expected this year. Impacts on spouses/partners work also affected participants in the study: ‘My husband's wages cut and scared of losing my job at [organisation name] and not given a verbally promised raise offered when I was hired.’

Workload

A considerable amount of respondents declared that due to the economic crisis, more colleagues were being made redundant. Due to job losses, workload has increased for those remaining employees. Of those who described the way the crisis had affected them, 37 said that their workload had increased (20% of New Zealand-born and 20% of overseas-born). One participant believed that ‘work is busier and there is definitely more work’. Another believed there were ‘more calls and higher work loads because of less staff to deal with it’. In addition, ‘having to take on extra load’ was one response, but that person later mentioned that it was for the greater good of the company. Another response consisted of ‘the hotel cuts down [costs] on all ends, especially staff, expecting one employee to do the work of three with the same shitty pay. Everyone is unhappy, overworked and dissatisfied, which is why so many people want to leave.’ Overall, according to the responses, due to cutbacks or loss of employees workload has increased within organisations. A few participants had benefitted from the widespread changes: ‘I'm a career consultant so very busy with unemployed/restructured people.’

Job Security

One of the main responses to the open-ended question was the fear of job loss. Ninety-three respondents described job security concerns (34% New Zealand-born and 38% overseas-born). One participant responded that she was from a ‘single income household, so job security is important to me and financial pressures may force a move’. Another participant said that it was harder to find a new job because more people are looking. On the other hand, some believed their job was secure: ‘Yes, looking for a house. More optimistic given a belief my job is safe.’ In addition, others stated that their job was secure but were not satisfied with their current work: ‘work-life has changed’ and it is ‘harder to find another job and I'm currently in a job which I'm not really enjoying’. Two other respondents stated that the economic crisis has affected their work life and personal life: ‘I can't afford a lot as is, let alone having to wait till I get fired’ and it is ‘very likely that I will have my contract terminated . . . I'm uncertain about how easy it will be to get another job’. Overall, job security was stated as a main concern and problem due to the uncertainty of the current economic crisis.

Disposable Income/Work Budgets

The most common effect of the crisis was budget cuts both in personal life and at work. One hundred and four respondents stated that there was some kind of budget cut in their life (47% New Zealand-born and 38% overseas-born). Reponses included: ‘I have to budget costs of living in order to survive’, ‘due to lack of income we have downsized the team’, and ‘aside from the general uncertainty caused by the crisis, my employer is looking at cost saving measures. The company is forcing staff to take leave to get leave balances down to a few days.’ In addition, many respondents had made a behavioural change, cutting costs in their personal life as well. Some typical responses were: ‘just made my family budget a bit stricter and limited spending’, ‘have to budget costs of living in order to survive’, and ‘I'm being more cautious how to spend money.’ ‘Cutting back on luxuries’ and decreasing credit card use were also frequently mentioned. Overall, most respondents in our sample had issues with budgets cuts due to the current economic crisis, be it personal or work related.

Job opportunity

Issues relating to the difficulty of locating a new job were also discussed. Overall, 37 of the responses were about job opportunities (16% of NZ born and 14% of overseas-born). One participant said, “I don't feel that leaving would be an option given the state of the market place” and another felt the economy had “limited the number of jobs available to apply for.” There was a consensus that there were “limited opportunities to move jobs.”

Likelihood to Leave

The second open-ended question focused on intentions and reasons for leaving New Zealand (‘Has the current state of the economy made you more likely to stay in New Zealand/return to your country of origin/ or go to another country; which and why?’). For the purposes of the initial analysis, responses were collapsed into two categories, stay in New Zealand or leave. For this question, 768 people who listed New Zealand as their place of birth and 354 who listed an overseas country of birth responded. Eighty-nine per cent of all those who answered the question would be more likely to stay in New Zealand because of the economic situation — 59.3% of the New Zealand-born group and 80.9% of overseas-born respondents. Thus participants were overwhelmingly more likely to remain in New Zealand due to the economic situation. For the overseas-born participants, there was a choice of returning to their country of origin, going to a third country or remaining in New Zealand. Onward migration was more common (6.7%) than return migration (4.8%).

A logistic regression was performed to examine the predictors of likelihood to leave New Zealand. While controlling for gender, age and organisation, place of birth (New Zealand/overseas) did not predict intention to leave, Exp(B) = .879, p = .69. Thus New Zealanders and overseas-born participants did not significantly differ on intention to leave New Zealand due to the state of the economy. See Table 2 for full reporting of this analysis. We further examined the likelihood of overseas-born participants leaving by length of residence. Those who had resided in New Zealand for less than 5 years were significantly more likely to intend to leave, χ2(1, N = 325) = 17.81, p < .001. Within the overseas-born group, those with nonpermanent residency status were significantly more likely to believe that they would leave, χ2(2, N = 327) = 11.59, p = .003.

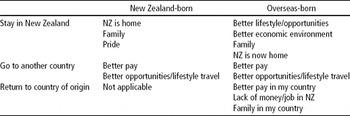

Table 1 Reasons to Leave or Stay

Table 2 Predictors of Likelihood to Leave New Zealand Due to the Economy

Note: *p < .01 **p < .001

^Organisation is dummy-coded (63 dummy variables), none of the dummy codes were significant at p < .05, the reported value is the maximum exp b.

Final model R 2 = .11 (Cox & Snell), .22 (Nagelkerke) −2 log likelihood = 584.57.

The related closed ended question, ‘How likely are you to stay in New Zealand if you lost your job?’, was answered with very likely, likely or not likely. These responses were combined into two categories, very likely/likely to stay or not likely. Overall, 87.8% of participants were likely/very likely to stay in New Zealand if they lost their job. For the overseas-born participants, 82.6% were likely/very likely to remain. Of the New Zealand-born, 90.8% were likely to remain. Performing a logistic regression, we controlled for gender, age and organisation, finding that place of birth (New Zealand/overseas) predicted intention to leave, Exp(B) = −.59, p = .006. Overseas-born participants were significantly more likely to intend to leave New Zealand if they lost their job. See Table 3 for full reporting of this analysis. Those with nonpermanent status were more likely to leave than those with permanent residence or citizenship, χ2(2, N = 352) = 24.95, p < .001. One interesting difference emerged in comparing age effects. Though age-predicted intention to leave New Zealand in both questions, younger New Zealand-born participants (under age 30) were more likely to intend to leave than older New Zealanders, χ2(1, N = 699) = 14.91, p < .001. However younger migrants were no more likely to intend to leave compared to older migrants, χ2(2, N = 310) = 3.45, p = .06. Following this analysis, the reasons to stay or go were then coded into themes using thematic analysis techniques described above.

Table 3 Predictors of Likelihood to Leave New Zealand If Job Lost

Note: *p < .01, **p < .001

^Organisation is dummy coded (63 dummy variables), largest organisational effect is reported, all p > .05.

Final model R 2 = .12 (Cox & Snell), .24 (Nagelkerke), −2 log likelihood = 770.49.

New Zealanders staying

Themes were coded initially for reasons that participants choose to stay in New Zealand. Three main themes were identified amongst New Zealand-born participants: New Zealand is home, family, and pride (love for New Zealand). ‘My family are here — if times get hard we would do what was necessary to support each other’ was one response. The ‘uncertain conditions’ overseas mentioned by a participant were typical, and there were perceptions of New Zealand's relative position being ‘better placed’ to weather the economic storms. One participant stated: ‘As the global downturn has attended all countries there would be little advantage in going overseas — the problem is worldwide, so there is a feeling that any country one went would be facing the same problems.’

Migrants staying

Four main themes were identified as reasons for migrants to remain in New Zealand: better lifestyle/opportunity, better economic environment, family, and New Zealand is now home. The migrants mostly felt ‘settled here’ and one said: ‘It's home and I feel our quality of life here is hard to beat.’ Another stated: ‘Unemployment is high back in Ireland now and being employed is a priority.” Moving during a global recession was considered ‘too risky’ for many. Overall, migrants stated more diverse reasons to stay than those born in New Zealand.

New Zealanders leaving

Three main themes were identified: better opportunities/lifestyle, better pay, and travel (to experience other parts of the world). Of those who listed a reason, the most common were increased pay (31%) or job opportunities (40.7%). A participant said that ‘overseas experience’ appealed to them and another stated ‘more jobs in my area’ as a reason to leave. A new experience/travel (24%) was a common reason. Taxes were only rarely mentioned (.04%). For those New Zealand-born participants who stated they would go to another country, the most likely destination was Australia (55.5%), and the United Kingdom (11%) was the next most common destination.

Migrants leaving

Three main themes were identified within the reasons migrants gave for a possible return to their country of origin: better pay in their country, lack of job/money (fixed term contracts) in New Zealand, and family in their country of origin. One migrant stated:

If it affects me directly and I lose my job, I would prefer to return to my country of origin. It is hard for migrants to find jobs even those who have lived here for many years. I would not want that stress and therefore would choose to return.

The reasons that migrants gave for considering onward migration were overwhelmingly pay/opportunity related. One participant stated: ‘more job opportunities, cost of life’.

Discussion

Even those with jobs feel the effects of an economic crisis. Through changes in personal and professional demands, the strain of the economy hits the pockets of the workers. Employees were most concerned with a drop in their own disposable income, most likely because this is the most proximal effect of the recession. These concerns had also changed behaviour, as participants reported reducing spending due to the economic climate.

Job security was the second largest concern on employees’ minds. Slightly more overseas-born participants were concerned about job security than New Zealand-born employees. Migrants may have more reason to fear job loss, with workplace discrimination or greater difficulty finding new jobs (North, Reference North2007). A recent Department of Labour survey found that 25% of migrants had experienced some form of discrimination, most frequently at work or in a public place (Masgoret, Merwood, & Tausi, Reference Masgoret, Merwood and Tausi2009).

Participants also reported more distal impacts, such as family members’ job losses, work colleagues made redundant, and children struggling to find work. Other concerns on the mind of employees were increases in workload, which leads to increased pressure on remaining employees (Selmer & Waldstrom, Reference Selmer and Waldstrom2007).

Results on psychological strains were divergent from those of previous literature. Levy and Sidel (Reference Levy and Sidel2009) found that due to economic crises individuals were more prone to stress, depression and low self-esteem. The current study did not measure these variables, but in their opened-ended responses employees rarely mentioned stress as a concern. One reason could be that despite initial feelings of anxiety and apprehension, the recession was generally perceived as a temporary occurrence, and something to which one can adapt (Fowler & Etchegary, Reference Fowler and Etchegary2008). Another possible explanation might be that to the economic crisis has not been as prominent in New Zealand as it is in other developed countries. Compared to US unemployment, which during the study period hit 10% nationally, New Zealand's unemployment remained relatively low in an international context (US Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2009). Passive downward social comparison may put in perspective the financial situation of New Zealanders compared to residents of countries that have been more affected by the crisis (Brewer & Weber, Reference Brewer and Weber1994; Wills, Reference Wills1981).

Does the economic crisis influence migration decisions? Overall, people tended to behave in a more conservative manner, saying that the economic situation had made them more likely to remain in New Zealand. The majority of employees prized stability and were more likely to stay in New Zealand than to leave for another country. This conservative approach likely indicates an increase in ‘rootedness’, as was observed in other countries during the economic crisis (Cooke, Reference Cooke2011), which also resulted in the sharp decrease of internal mobility. Reasons given by participants included that the economic crisis has had less impact on New Zealand than other parts of the world, reducing the prospects of employment overseas and tending to make people stay in their current employment rather than the ‘risky’ choice of moving.

However, when asked what they would do if they lost their job, about 12% said they would leave the country. Overseas-born and particularly those with nonpermanent visa status were more likely than New Zealand-born participants to leave. Though younger New Zealanders are more likely to leave than older New Zealanders, age was not related to likelihood of leaving in the migrant sample. Previous research found that as long as return migration costs are relatively low, workers who experience worse-than-expected outcomes in the United States may wish to return to their home country (Borjas & Bratsberg, Reference Borajas and Bratsberg1996). Because of New Zealand's geographic position, only migration to Australia would be considered relatively low cost, and this is a likely consideration in the appeal of trans-Tasman migration. In our study, Australia was the primary destination listed by those who would consider leaving. The trans-Tasman migration pattern is cyclic, relating to many macroeconomic factors (asynchronous boom and bust cycles, wage differentials), as well as societal changes (the acceptance of an overseas experience [OE] as a rite of passage for young people; Green, Power & Jang, Reference Green, Power and Jang2008; Poot, Reference Poot2009). Recently, the Australian economy grew rapidly while the New Zealand economy stagnated and this likely impacted many people's decisions, as once again there has been a strong upturn in trans-Tasman migration (Statistics New Zealand, 2011).

Migrants gave more reasons to stay in New Zealand, often focusing on comparative factors (better lifestyle/opportunities, better economic environment). Both migrants and non-migrants stated that a main reason to stay was that ‘New Zealand is home’ and that they have family in the country. These attachment and social reasons are very much in line with international research on place attachment (Hernandez, Carmen Hidalgo, Salazar-Laplace, & Hess Reference Hernandez, Carmen Hidalgo, Salazar-Laplace and Hess2007). Both groups felt that better pay and lifestyle could be a reason to go to another country. For migrants, better pay in the country of origin and family in the country of origin were also reasons to consider going back. These results are congruent with previous research that focused on social, psychological and economic factors influencing the decision to leave or stay (Constant & Massey, Reference Constant and Massey2003). New Zealanders would be expected to express migration interest because of the cultural acceptance of time spent living overseas, the OE, often seen as a part of early career progression and personal growth (Inkson & Myers, Reference Inkson and Myers2003). Though political rhetoric has focused on taxes as a reason people leave New Zealand (Chapman, Reference Chapman2011), job opportunities and increased pay were the predominant reasons given by both migrants and New Zealanders. As in previous research, lack of job opportunities in the adopted country and family support in the country of origin were important in many migrants’ decisions to return (Dashefsky, DeAmicis, Laserwitz, & Tabory, Reference Dashefsky, DeAmicis, Laserwitz and Tabory1992; Ley & Kobyashi, Reference Ley and Kobayashi2005).

Policy Implications

Overall, New Zealand workers are a highly mobile group, who are aware of international opportunities and economic dynamics. As the historical pattern has been for New Zealand to lack skilled workers, and for so many of New Zealand's university educated citizens to leave, policymakers should avoid adjustments to the migration system that limit new migrants’ ability to gain residence, despite rising unemployment. What may appear to be protecting New Zealanders’ ability to find work may result in severe skills shortages when the country attempts to expand its economy. The conservative approach that workers take during a recession is likely to change quickly as more opportunities become available in other countries. Policies which support employers’ ability to retain skilled workers are also important, as our findings suggest that 12% of workers would consider leaving New Zealand if they lost their job.

Limitations and Future Research

The study had several strengths and limitations. The sample size was one of its strengths, but the general sample was only those of employed persons and did not include employees who have remained unemployed after being made redundant. An additional strength was the use of qualitative measures, as it further explored the concerns of individuals as they experience them. Further research should involve stress measures, different populations, and more emphasis on quantitative associations.

Another limitation was that most businesses used in the study were in the greater Wellington region. Thus it may not represent the whole New Zealand population, particularly since Wellington is the capital city and the government is the largest employer. It has also been interesting to note the number of Christchurch residents who have moved abroad following the series of earthquakes, again indicating that economic conditions may not be the primary factor in a decision to migrate. Further research should take into account other major cities in New Zealand, as well as rural areas where the employment base is more limited.

During the year over which data was collected, the economy of New Zealand worsened (Department of Labour, 2009; Statistics New Zealand, 2009, 2010). Thus those answering at the beginning of the study period were facing a global crisis, but not a local one. By the end of the study period, the unemployment rate had increased. A further study would ideally include people's reactions over time, to more thoroughly examine if the economic situation is truly influencing their desire to move abroad. It would be useful to conduct a similar study in a prosperous economic situation, as there is no baseline or control in this study. This type of study could explore if there is an equal amount of desire to move abroad during good economic times as in recessionary periods.

Despite these limitations, this research has made an important contribution to the debate about emigration from New Zealand, particularly the departure of New Zealand-born workers, as well as the onward and return migration of migrants. Rhetoric that claims New Zealand could do more to retain workers is partially supported, but the picture is complex and points to the idea that emigrants’ motivations go beyond simply acting in economic self-interest. Additionally, the study illuminates the concerns of both migrant and host national workers during a period of extreme international economic uncertainty.