For many people, the search for profound self-understanding and a life built around it is an eternal, imperfect pursuit. To this end, positive psychology has begun to offer many answers to the question of how to best promote and enhance well-being. In the current research, we propose that self-connection, as a distinct construct rooted in self-awareness, is an important means of increasing one’s well-being. As an initial examination of this proposition, we present two studies that examine the role of self-connection in increased well-being. Both studies test a proposed model that views self-connection as both an independent predictor of well-being as well as a mediator of the relationship between mindfulness and well-being. We use two operationalizations of well-being to understand the generalizability of these relationships.

Mindfulness and well-being

For decades now, mindfulness practices have become a part of many people’s everyday lives (Tart, Reference Tart1990). For our purposes, we use the definition of mindfulness promoted by Kabat-Zinn (Reference Kabat-Zinn1994); that is, mindfulness is “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally” (p. 4). In general, mindfulness is a strong and consistent predictor of well-being. Mindfulness practitioners report several lasting positive effects, including an increased sense of well-being and compassion (Baer, Lykins, & Peters, Reference Baer, Lykins and Peters2012), increased quality of life, decreased depression, anxiety, chronic pain and physical disability, and improved coping patterns (Grossman, Niemann, Schmidt, & Walach, Reference Grossman, Niemann, Schmidt and Walach2004). Similarly, research suggests that brief mindfulness interventions are effective in improving a variety of well-being indicators, including perceptions of quality of life, compassion, job burnout (Fortney, Luchterhand & Zakletskaia, Reference Fortney, Luchterhand and Zakletskaia2013) and quality of sleep (Hülsheger et al., Reference Hülsheger, Lang, Depenbrock, Fehrmann, Zijlstra and Alberts2014). Overall, the evidence is strong that an increase in mindfulness correlates with an increase in well-being.

Self-connection

We define self-connection as a subjective experience consisting of three components: (1) an awareness of oneself, (2) an acceptance of oneself based on this awareness, and (3) an alignment of one’s behavior with this awareness (see Klussman, Curtin, Langer, & Nichols, Reference Klussman, Curtin, Langer and Nichols2019). In this way, the first component of self-connection is consistent with recent conceptualizations of the self (Schlegel & Hicks, Reference Schlegel and Hicks2011; Schlegel, Hicks, Arndt, & King, Reference Schlegel, Hicks, Arndt and King2009). However, while the self is considered an internal and potentially private phenomenon, our definition of self-connection goes beyond just the internal to focus on the degree to which a person is attuned to an essential inner self, accepts that self, and aligns their behavior with that inner self. Thus, our construct incorporates both a private experience and public behavioral expressions of one’s self. We suggest that self-connection is central to well-being because it provides people with a sense of consistency between internal desires and external behaviors, as well as an acceptance of those internal desires.

Importantly, self-connection is significantly distinct from mindfulness in several ways. First, unlike self-connection, mindfulness often hesitates to acknowledge the existence of the self, and often requires one to distance from such a notion (Bernstein et al., Reference Bernstein, Hadash, Lichtash, Tanay, Shepherd and Fresco2015). Second, although mindfulness does focus on an awareness of oneself (not “the self”), the component of non-judgmental awareness is quite different from self-acceptance. In fact, acceptance requires knowing and positively evaluating oneself. Non-judgmental awareness, in contrast, simply requires one to have no valence associated with oneself (Kabat-Zinn, Reference Kabat-Zinn1994). We propose that mindfulness consists of awareness and a component that may lead to acceptance, but it is not equivalent to the experience of self-connection. Finally, mindfulness does not include an external, behavioral component analogous to alignment in self-connection (e.g., Chatzisarantis & Hagger, Reference Chatzisarantis and Hagger2007). That is, it focuses solely inward and does not recognize the importance of aligning one’s behavior with one’s internal self. Consistent with these assertions, preliminary evidence suggests that self-connection uniquely predicts several indicators of well-being and may even do so beyond what mindfulness does (Klussman, Nichols, Curtin, & Langer, Reference Klussman, Nichols, Curtin and Langer2019).

Mindfulness and self-connection

Despite these differences, we propose that mindfulness and self-connection are importantly related. Across many definitions, a sense of awareness is often one of the key factors in being mindful (Baer, Reference Baer2011). In fact, researchers have suggested that it is one of two core components of mindfulness: “the self-regulation of attention so that it is maintained on immediate experience, thereby allowing for increased recognition of mental events in the present moment” (Bishop et al., Reference Bishop, Lau, Shapiro, Carlson, Anderson, Carmody and Devins2004, p. 232). In this way, mindfulness and self-connection share a core component. Carlson (Reference Carlson2013) also suggests that mindfulness is one important means of developing self-awareness and self-acceptance – both of which are central to our definition of self-connection (Klussman, Curtin et al., Reference Klussman, Curtin, Langer and Nichols2019). By improving people’s ability to see themselves and their behavior more objectively, and by helping defuse ego-protecting mechanisms that hinder self-awareness, mindfulness is a promising means of building self-connection and thus serves as a starting point for the current research.

Self-connection and well-being

As such a broad construct, there are many paths by which people can increase their well-being (e.g., Roberts, Ong, & Raftery, Reference Roberts, Ong and Raftery2018; Zuo, Wang, Wang, & Shi, Reference Zuo, Wang, Wang and Shi2017), and there are several reasons to think that self-connection may predict well-being. First, previous research has established that both the perceived self and authenticity, two concepts that are proposed to strongly relate to self-connection (Klussman, Curtin et al., Reference Klussman, Curtin, Langer and Nichols2019), are associated with well-being (Goldman & Kernis, Reference Goldman and Kernis2002). Heppner and colleagues (Reference Heppner, Kernis, Nezlek, Foster, Lakey and Goldman2008) found that the degree to which participants indicated that they felt in touch with their self was associated with increased self-esteem and positive affect and decreased negative affect. The feeling that you know your self also predicts self-actualization, vitality, self-esteem, active coping, psychological need satisfaction, and subjective well-being (Schlegel, Vess, & Arndt, Reference Schlegel, Vess and Arndt2012).

Similarly, Goldman and Kernis (Reference Goldman and Kernis2002) found that authenticity correlated with increased self-esteem and life-satisfaction, and decreased contingent self-esteem and negative affect (see also Kernis & Goldman, Reference Kernis, Goldman, Forgas, Williams and Laham2004, Reference Kernis and Goldman2006). This is consistent with Sheldon’s goal congruence model (Sheldon, Reference Sheldon2014) and his findings that pursuing goals that are true to one’s sense of self predicts well-being (Sheldon & Elliot, Reference Sheldon and Elliot1999; Sheldon et al., Reference Sheldon, Elliot, Ryan, Chirkov, Kim, Wu, Demir and Sun2004). Wiesmann and Hannich (Reference Wiesmann and Hannich2013) similarly found that having a sense of coherence significantly predicted life satisfaction in older adults. Thus, aspects of our conceptualization of self-connection are known to correlate with various aspects of well-being and life satisfaction and support our proposition that self-connection enhances well-being.

Current research

Past research has established the relationship between mindfulness and well-being but has yet to explain why this relationship exists. In the current research, we investigated the potential for self-connection to partially explain this relationship. In particular, we examined whether self-connection is a significant mediator of the association between mindfulness and well-being (see Figure 1 for our proposed model). We expected that the association between mindfulness and well-being is partially mediated by self-connection – in other words, that an increase in self-connection partially explains the relationship between mindfulness and well-being.

Figure 1. Mediation model and results.

To examine aspects of both eudaimonic and hedonic well-being, we performed two studies examining these two forms of well-being (Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2001). Consistent with contemporary conceptualizations of well-being (Heintzelman, Reference Heintzelman, Diener, Oishi and Tay2018), we operationalize eudaimonic and hedonic well-being in the current research as flourishing and life satisfaction. Flourishing consists of multiple factors, including social relationships and social capital, a sense of hope and optimism, an interest and engagement with different activities, and perceived competence in domains of importance to the individual (Diener et al., Reference Diener, Wirtz, Tov, Kim-Prieto, Choi, Oishi and Biswas-Diener2010). Life satisfaction, on the other hand, focuses on a general satisfaction with one’s life. Between these two operationalizations, we can understand multiple components of well-being and examine the extent to which our proposed relationships hold across these aspects of one’s well-being.

Based on the existing literature and our conceptualization of self-connection, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 The more mindful people are, the higher their well-being will be.

Hypothesis 2 The more mindful people are, the more self-connected they will be.

Hypothesis 3 The more self-connected people are, the higher their well-being will be.

Hypothesis 4 Self-connection will mediate the relationship between mindfulness and well-being.

Study 1

In the first study, we asked participants to answer a questionnaire that included measures of mindfulness, self-connection and well-being. Of note, we used flourishing as our measure of well-being due to the plethora of research that has operationalized well-being in this way (Huppert & So, Reference Huppert and So2013).

Method

Participants

The study was reviewed and approved by an independent Institutional Review Board. We recruited participants via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (i.e., MTurk). The only qualifications we set were for participants to live in the United States and to be “Masters” on MTurk. To accomplish 80% power with medium-sized direct effects of the predictor on the mediator, the mediator on the outcome and the indirect effect of the predictor on the outcome (Fritz & MacKinnon, Reference Fritz and MacKinnon2007), we recruited 101 participants to complete the survey in exchange for $3. See Table 1 for sample demographics.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants in Studies 1 and 2

Note: n = 101 for Study 1; n = 104 for Study 2.

Measures

Mindfulness

We assessed mindfulness using Feldman, Hayes, Kumar, Greeson, and Laurenceau’s (Reference Feldman, Hayes, Kumar, Greeson and Laurenceau2007) Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale – Revised (CAMS-R). Participants rated 12 items on a 4-point scale. A sample item is “I can accept things I cannot change” (1 = rarely/not at all; 4 = often/always). Higher scores reflect greater mindfulness (M = 3.01; SD = 0.57; α = 0.90).

Self-connection

Our measure of self-connection consisted of one item. In the instructions of the study, we first defined self-connection as “being aware of your values, goals, beliefs, and attitudes, and acting in a way that is consistent with those internal states”. Later in the questionnaire, we asked participants to “Please select the answer below that best describes you”. Participants indicated how well our description of self-connection fit them using a 7-point scale (1 = I rarely or never feel self-connected; 4 = sometimes I feel self-connected, and sometimes I do not feel self-connected; 7 = I always or often feel self-connected). Higher scores indicated greater self-connection (M = 5.43; SD = 1.26).

Flourishing

Diener and colleagues’ (2010) Flourishing Scale served as our first indicator of well-being. Participants rated how much they agreed with seven statements (e.g., “I am a good person and live a good life” from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). The original scale has eight items, but one item (“People respect me”) was left out of our survey due to a transcription error. Higher scores indicated greater flourishing (M = 5.46; SD = 1.25; α = 0.95).

Demographics

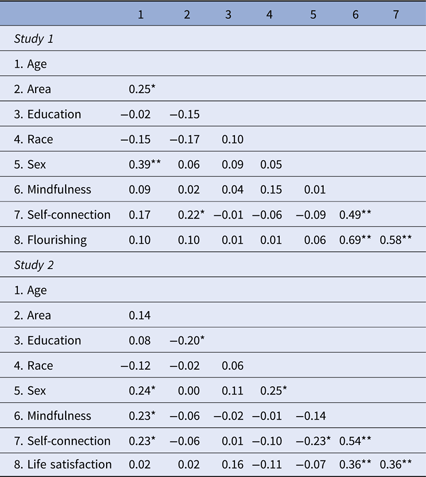

We additionally measured several demographic characteristics to understand the composition of our sample. These included age, area of residence (i.e., urban, suburban, rural), education, race and sex. Given the abundance of evidence suggesting the effects of demography on well-being, we also controlled for these variables in our analyses (e.g., Horley & Lavery, Reference Horley and Lavery1995; Witter, Okun, Stock, & Haring, Reference Witter, Okun, Stock and Haring1984). See Table 2 for correlations among all variables.

Table 2. Correlations between variables of interest in Studies 1 and 2

Note: *p < .05; **p < .01; n = 101 for Study 1; n = 104 for Study 2.

Results and discussion

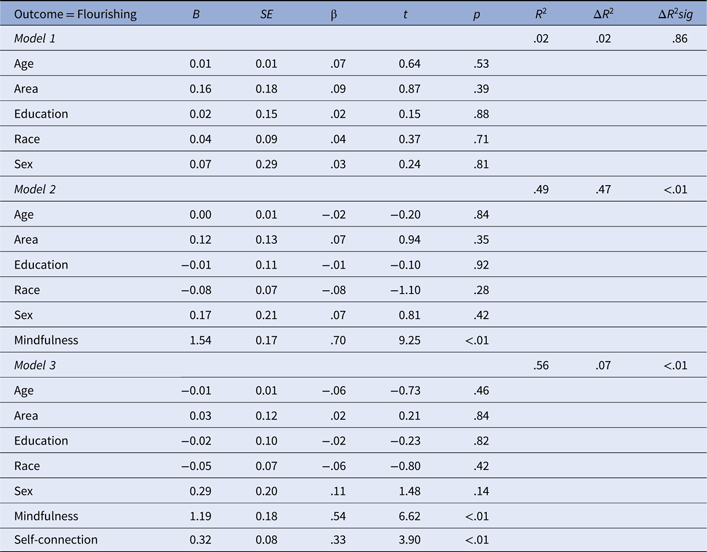

To test our hypotheses, we employed version 24 of IBM’s SPSS Statistics. In particular, we followed the steps suggested by Baron and Kenny (Reference Baron and Kenny1986) to test mediation. First, we regressed flourishing on mindfulness, then self-connection on mindfulness, and finally flourishing on both mindfulness and self-connection (as simultaneous predictors). Across all regressions, we controlled for age, area of residence, education, gender and race.

In general, all hypothesized predictors significantly related to each outcome in each regression. In support of Hypothesis 1, mindfulness was significantly related to flourishing (β = .70, p < .01). Similarly, Hypothesis 2 was supported, as mindfulness and self-connection were significantly related (β = .49, p < .01). Consistent with Hypothesis 3, self-connection correlated with flourishing, even after controlling for mindfulness (β = .33, p < .01). The relationship between mindfulness and flourishing remained significant as well (β = .54, p < .01). However, and in support of Hypothesis 4, a Sobel test score of mediation confirmed self-connection partially mediated the relationship between mindfulness and flourishing (z = 3.21, SE = 0.11, p < .01). Overall, mindfulness appears to be strongly related to flourishing. In addition, the findings support our expectation that greater mindfulness leads to greater well-being, partially due to mindful people being more self-connected (see Table 3). That is, the more mindful people are, the greater is their experience of flourishing in part because they are more self-connected.

Table 3. Regression results for Study 1

Note: n = 101.

Study 2

The results from Study 1 supported all four of our hypotheses that used flourishing as an operationalization of well-being. In the second study, we asked a separate set of participants to answer a questionnaire that included measures of mindfulness, self-connection and well-being. However, instead of using flourishing as our measure of well-being, the current study examined life satisfaction. As an important aspect of subjective well-being (Diener, Reference Diener1984), our goal was to further support our hypotheses and to better generalize them to overall well-being.

Method

Participants

We recruited a new set of participants via MTurk. For this sample, we only required that participants lived in the United States. Again, in line with Fritz and MacKinnon (Reference Fritz and MacKinnon2007), we recruited 104 participants to complete the survey in exchange for $3. See Table 1 for sample demographics.

Measures

Mindfulness

We again assessed mindfulness using Feldman et al.’s (Reference Feldman, Hayes, Kumar, Greeson and Laurenceau2007) CAMS-R using a 4-point scale (1 = rarely/not at all; 4 = often/ always). Higher scores again reflect greater mindfulness (M = 2.93; SD = 0.51; α = .85).

Self-connection

We again used our one-item measure of self-connection using a seven-item scale to “Please select the answer below that best describes you” (1 = rarely or never feel self-connected; 4 = sometimes I feel self-connected, and sometimes I do not feel self-connected; 7 = I always or often feel self-connected). Higher scores again indicated greater self-connection (M = 5.35; SD = 1.28).

Life satisfaction

To operationalize well-being in the current study, we measured life satisfaction with the single-item measure validated by Cheung and Lucas (Reference Cheung and Lucas2014). It reads, “In general, how satisfied are you with your life?” and has a 4-point scale (1 = very satisfied; 4 = very dissatisfied). We reverse-coded the item so that higher values represented higher life satisfaction (M = 2.89; SD = 0.87).

Demographics

We additionally measured the same demographic characteristics as in Study 1. These included age, area of residence (i.e., urban, suburban, rural), education, race and sex. See Table 2 for correlations among all variables.

Results and discussion

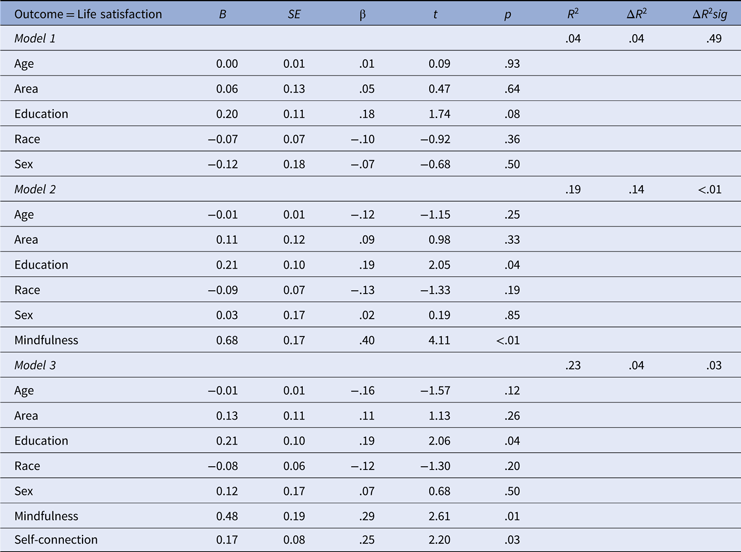

Similar to Study 1, we ran three regressions using version 24 of IBM’s SPSS Statistics. First, we regressed life satisfaction on mindfulness, then self-connection on mindfulness, and finally life satisfaction on both mindfulness and self-connection (as simultaneous predictors). Across all regressions, we again controlled for age, area of residence, education, gender and race.

In general, all predictors significantly predicted all outcomes in each regression (see Table 4). In support of Hypothesis 1, mindfulness significantly related to life satisfaction (β = 40, p < .01). Similarly, Hypothesis 2 garnered more support, as mindfulness and self-connection were again significantly related (β = .47, p < .01). Consistent with Hypothesis 3, self-connection was related to life satisfaction, even after controlling for mindfulness (β = .25, p = .03). The relationship between mindfulness and life satisfaction also remained significant (β = .29, p = .01). However, and in support of Hypothesis 4, a Sobel test of mediation confirmed self-connection partially mediated the relationship between mindfulness and life satisfaction (z = 2.04, SE = 0.10, p = .04).

Table 4. Regression results for Study 2

Note: n = 104.

General discussion

The current research sought to examine whether self-connection mediates the well-established relationship between mindfulness and well-being. Furthermore, we did so across two studies to test the generalizability of these relationships by operationalizing well-being as both flourishing and life satisfaction. As expected, and consistent with past research, mindfulness significantly predicted well-being. In addition, self-connection partially explained the association between mindfulness and well-being. That is, the more mindful people were, the more self-connected they were; the more self-connected they were, the greater was their well-being. These findings suggest that self-connection is an important result of developing an effective mindfulness practice and helps explain how mindfulness fosters overall well-being.

Implications

As researchers become increasingly interested in the mechanisms that underlie well-being (Garland, Hanley, Goldin, & Gross, Reference Garland, Hanley, Goldin and Gross2017; Shapiro, Carlson, Astin, & Freedman, Reference Shapiro, Carlson, Astin and Freedman2006), self-connection appears to be an important variable that can contribute to this investigation. In the current research, we tested a model that helps explain how mindfulness can foster an increased sense of connection to self and, downstream, well-being. Our results suggest that self-connection can help explain how everyday practices such as mindfulness foster overall well-being. Self-connection as a whole, and its relationships with mindfulness and well-being in particular, are promising avenues for future well-being research to embark on.

The practical implications of self-connection are also significant. Given that flourishing is a marker of high psychological functioning and increased physical health (Keyes, Reference Keyes2007), it is important for researchers to find ways to bolster individual differences that encourage both. The fact that people’s subjective assessment of self-connection was a predictor of well-being suggests that we may be able to affect change in perceptions that will increase well-being and even health. Researchers and practitioners alike may be wise to incorporate self-connection into their treatment of well-being and may want to explore ways to increase self-connection through both mindfulness practices and other promising activities that facilitate an internal focus and acceptance of oneself.

Limitations and future directions

A few limitations to this research must be acknowledged. The first is that the measures of self-connection and life satisfaction used in the current study consisted of only one item. However, an abundance of research suggests that single-item measures are both valid and reliable (Nagy, Reference Nagy2002, Nichols & Webster, Reference Nichols and Webster2013, Reference Nichols and Webster2014). In addition, these items have been successfully employed, and have demonstrated adequate validity, in previous research (e.g., Cheung & Lucas, Reference Cheung and Lucas2014; Klussman, Nichols, Langer, & Curtin, Reference Klussman, Nichols, Langer and Curtin2020). Nonetheless, given that the definition of self-connection has three potentially independent components, a more nuanced multi-item measure might allow researchers to test whether it is awareness, acceptance or alignment (or a combination of them) that predicts well-being. Considering the multifaceted nature of mindfulness, future research would benefit from examining both constructs, including their specific components, to shed light on all the ways this relationship might emerge.

The study is also limited by its cross-sectional design. Although we propose a set of directional relationships consistent with existing research, we cannot test for causality, and it is possible that the relationships between these variables are dynamic and multidirectional. For example, it may be that people who are high in self-connection undertake additional mindfulness practices to maintain their connection to self. Examining these relationships over time would help to better understand exactly what the causal direction of them is. Longitudinal research would also enable researchers to examine whether certain aspects or operationalizations of mindfulness best predict well-being through certain components of self-connection.

The current findings also raise a number of different questions and avenues for further self-connection research. For example, it would be worth understanding the many ways in which people might foster self-connection. Within mindfulness, certain aspects may be most impactful and may also depend on the conceptualization of mindfulness that one adopts. Beyond mindfulness, other activities might also focus people internally and may facilitate self-connection. Additionally, it is important to examine ways in which self-connection can help people develop a deeper sense of well-being. We found here that greater self-connection predicted greater flourishing and life satisfaction. However, we do not yet know why or how this occurs, and research would be wise to examine this in the future.

Conclusion

We propose that self-connection is an important predictor of well-being. This research suggests that self-connection relates to mindfulness, and that it is significantly related to well-being, as measured both by flourishing and life satisfaction. In addition, self-connection partially accounts for the relationship between mindfulness and well-being. Given the empirical and practical significance of increased well-being, self-connection appears to be a promising mechanism that deserves further attention. Exploring self-connection may allow researchers and practitioners to contribute to the ongoing efforts to make people’s lives better through increasing various aspects of one’s well-being.

Financial support

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.