Literature suggests that depression is conceptualized differently among cultures (e.g. Kirmayer, Reference Kirmayer2001; Kleinman Reference Kleinman2004). Neglecting to take these cultural distinctions into account may lead to inaccurate diagnosis or inappropriate treatment of certain groups. There have been few studies that have investigated the Filipino conceptualization of depression. These studies do suggest that Filipinos have shown a distinct expression of the disorder. Such findings thus challenge the use of standardized measures of depression for this population. To date, there have not been any studies that have examined the factor structure of the CES-D among Filipinos residing in the Philippines.

To study the Filipino's conceptual understanding of depression, a sample of Filipino seafarers was surveyed. Seafaring is considered on of the highest risk, stressful and dangerous occupations. Besides the physical challenges of the job, psychological well-being can also be compromised. Loneliness, separation from family, lack of shore leave, job instability, and the possibility of piracy are factors that have been found to affect seafarer mental health (Iversen, Reference Iversen2012). Using a sample of 135 Filipino seafarers, this study has found a three-factor structure of the conceptualization of depression. Factor I consists of a combination of depressed affect items and somatic retardation items, Factor II consists of a combination of interpersonal items, depressed affect and one somatic retardation item, and Factor III consists of positive affect items. The combination of depressed affect items and somatic retardation items is an interesting finding, similar to those of other Asian cultures (Kuo, Reference Kuo1984 & Ying, Reference Ying1988), and similar to a study of adolescent Filipino-Americans (Edman, Danko, Andrade, Mc Ardle, Foster, & Glipa, 1998) suggesting that Filipinos do not differentiate physical symptoms from emotional ones. The implications of these findings in understanding depression from a Filipino perspective are discussed.

Review of related literature

Culture and the unique manifestation of depression

There is growing appreciation, receptivity, and action towards the understanding and utilization of cultural factors in the study of the depressive experience (Marsella, Reference Marsella, Lonner, Dinnel, Hayes and Sattler2003). This is based on the evolving research that has shown different manifestations of depression across cultures. For example, research evidenced the presence of local symptoms of depression not typically listed in the diagnosis of the disorder (Bolton, Reference Bolton2001). Furthermore, symptoms reported by those suffering major depressive disorder across Asia reported differences from one country to another (Sulaiman, Bautista, Liu, Udomratn, Bae, Fang, Chua, Liu, George, Chan, Tian-mei, Hong, Srisurapanont, Rush, & the Mood Disorders Research: Asian & Australian Network, Reference Sulaiman, Bautista, Liu, Udomratn, Bae, Fang, Chua, Liu, George, Chan, Tian-mei, Hong, Srisurapanont and Rush2014). Analyses revealed that while these differences were not necessarily significant to alter treatment, they are important in terms of diagnosing major depressive disorder in different milieu.

These differences are noted in studies that explore culture as a significant factor in understanding psychopathology, particularly depression (Kleinman, Reference Kleinman2004). Characteristics of depression across cultures do not vary simply by prevalence, but also by individual reported symptoms, including experiences of somatization, feelings of guilt, and expression of positive affect (Juhasz, Eszlari, Pap, & Gonda, Reference Juhasz, Eszlari, Pap and Gonda2012). Cultural differences of depressive expression have been observed between Asian Americans and European Americans, with Asians underreporting symptoms such as fatigue and feelings of guilt (Kim & Lopez, Reference Kim and Lopez2014). On the other hand, Marsella's (Reference Marsella, Lonner, Dinnel, Hayes and Sattler2003) investigation on depression across cultures reveals that somatic symptoms and physical complaints often dominate the presentation of depressive experiences in non-Western cultures and that self-deprecation, suicidal ideation and behaviors, and existential grievances tend to be less common.

Meta-analysis of the work with different ethnic groups strongly suggests that there exist key similarities as well as differences in the experiences of depression. Different cultures conceptualize the problem of depressive symptoms in different ways, and that there may even be no equivalent concepts for depression in certain non-Western cultures (Kim, DeCoster, Huang, & Chiriboga, Reference Kim, DeCoster, Huang and Chiriboga2011).

Given the scarcity of knowledge in culture-specific experiences of mental health disorders, there may be merit in a deeper exploration of the idiosyncratic features of depression in specific cultures, such as the Filipino culture.

Asian culture and the CES-D

A segment of the literature on depression utilizes CES-D in order to understand how cultures conceptualize this experience. Many of these studies, using an Asian sample, acknowledge the existence of a unique structure of the factors of depression. A study of adults in a Chinese community (Ying, Reference Ying1988) found that affective and somatic dimensions of depression are factored together, suggesting a lack of differentiation between psychological and bodily issues. Lee and colleagues’ study (Reference Lee, Sunita, Byrne, Wong, Ho, Lee and Lam2008) of Hong Kong adolescents confirmed 2 models of depression, where, in either model, the positive experience did not emerge at all, and fit poorly with the scale for the sample. A study by Edman, Danko, Andrade, McArdle, Fostor, and Glipa (Reference Edman, Danko, Andrade, McArdle, Foster and Glipa1999) found that Filipino-Americans differ on the symptoms of depression when measured on the CES-D. In particular, Filipino-Americans did not tease apart depressed affect from somatic-retardation symptomatology. Furthermore, they integrate interpersonal items with the same factor as depressed affect and somatic retardation symptoms. On the other hand, a study comparing Chinese, Filipino, and European American adolescents (Russell, Crocket, Shen, & Lee, Reference Russell, Crockett, Shen and Lee2008) found that Filipinos shared the same factor structure of the CES-D as European Americans, although strong and strict invariance was evident for less than half of the items.

The current research on the structure of depression in Filipinos, and specifically the factor structure of depression as assessed with the CES-D, therefore appears to be limited solely to a few studies largely focusing on a Filipino-American sample. This is problematic because Filipinos represent a large and internationally distributed population. As of 2015, the government of the Philippines estimated that the population of the Philippines was 100.98 million people (Philippines Statistics Authority, 2016), making it the thirteenth most populous country in the world (CIA, 2017). In addition to the weight of this population, the Philippines are also a major contributor of foreign and overseas workers: a 2014 estimate of Filipino overseas workers estimated that more than 10 million Filipinos work internationally (Commission on Filipinos Overseas, 2014). Without a better understanding of the phenomenology of depression in Filipinos, clinical psychologists in the Philippines and internationally may be missing important information about the specific presentation and construction of depression in Filipino patients that they see.

Statement of the problem

This current study uses factor analysis to explore possible idiosyncratic manifestations of depression in Filipinos in the Philippines. The question this research seeks to answer is as follows: Do Filipinos display a unique conceptual structure in terms of their expression of depression? Specifically, this study seeks to investigate the factor structure of the CES-D that emerges from Filipino seafarers. Like many other cross-cultural studies in this area, this study will also compare its findings with Radloff's (Reference Radloff1977) original factor structure, which includes Depressed Affect, Positive Affect, Somatic Retarded Activity, and Interpersonal.

This paper hypothesizes that there exists a culture-specific structure of depression among Filipinos. The study examines the factors at play for Filipino seafarers and analyses the key responses therein. By identifying these factors, there might be more accuracy in the assessment of depression among a local Filipino population.

Method

Data sources

Data of this study were obtained from 135 participants. Researchers contacted seafaring shipping organizations and non-profit organizations to liaise with seafarers, as well as approaching them directly through personal contact. Selection was accomplished through snowball sampling. One hundred 175 participants provided some answers, of which 40 were dropped from this study because of incomplete responses to the CES-D. The final sample was therefore composed of 135 male seafarers of Filipino citizenship. Age mean was 39.55 (SD 11.5) and age range was 21–63. See Figure 1 for a distribution of age in the sample. Other demographic questions included self-identified religiosity (92.6% yes, 3.7% no, 3.7% no answer) and marital status (73.3% married, 23.4% not married, 3% no answer).

Figure 1 Histogram of age distribution in sample

Data collection

As part of a larger study, researchers sat down with respondents with a battery of quantitative tests, which included the Center of Epidemiological Studies – Depression scale (CES-D). Through informed consent, all respondents were informed that their participation in the study was completely voluntary. The tests were administered using semi-structured interviews in order to facilitate understanding and clarity. Participants answered questions together with the researchers, and researchers took note of responses via pen-and-paper. Any additional remarks or details the participant wished to share were also noted. All responses were entered into SPSS for storage and qualitative notes kept for future reference and study.

Measures

The CES-D (Radloff, Reference Radloff1977) is a widely used scale used to measure the depressive symptomatology among the general population. It has been used repeatedly in the Philippines and with Filipino populations in previous research (e.g. Kuo, Reference Kuo1984; Russell, Crockett, Shen, & Lee, Reference Russell, Crockett, Shen and Lee2008; Urada, Morisky, Pimentel-Simbulan, Silverman, & Strathdee, 2012). The CES-D scale examines the respondents on four variable clusters namely Depressive Affect, Interpersonal, Somatic Retardation, and Positive Affect. These are measured on a five-point scale, with high scores indicating potential depressive symptoms. The scale was translated into Filipino and then back-translated into English to assess validity. Translation discrepancies were reconciled by bilingual researchers.

Analyses

Data were exported from .sps format to .csv for analysis. All analyses were conducted using RStudio v1.0.136. The initial analyses conducted were a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using the lavaan package in R. The CFA was used to assess the fit of the general-accepted 4-factor structure for this sample. This analysis generates a not positive definite covariance matrix of latent variables. See Table 1 for model-generated covariance matrix.

Table 1 Model-generated covatiance matrix

This failure may be due to several reasons, including the fact that this factor structure is inappropriate for this sample or alternately that the sample size is too small for the analysis (Wothke, Reference Wothke, Bollen and Long1993). In this case, either reason may be suspected: previous research with Filipino-Americans suggested that the 4-factor structure is not appropriate (Edman et al Reference Edman, Danko, Andrade, McArdle, Foster and Glipa1999). However, a recommended sample size for CFA is (k+1)(k+2)/2 where k is the number of indicators (Flora & Curran, Reference Flora and Curran2004; Jöreskog & Sörbom, Reference Jöreskog and Sörbom1996). In this case, the sample size of 135 is below the recommended sample size of 231 using this guideline. Regardless of the reason, a non-positive definite covariance matrix means that the 4-factor structure CFA does not provide an appropriate analysis for this sample. We moved to EFA.

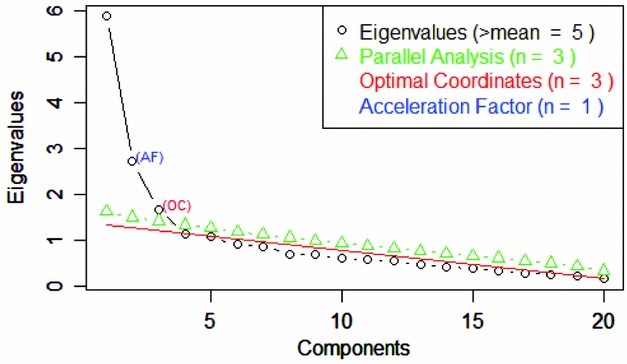

Following this analysis, Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was used to identify a well-fitting factor structure. EFA was conducted using the nFactors package and factanal command in R. Initial analyses explored the appropriate number of factors to extract. Using the Optimal Coordinates assessment (Raîche, Walls, Magis, Riopel, & Blais, Reference Raîche, Walls, Magis, Riopel and Blais2013), three factors were identified as the appropriate factor structure (See Figure 2).

Figure 2 Scree plot and results of non-graphical tests of factor structure

A three-factor model was identified using the factanal command in R, with varimax rotation. This command performs a maximum-likelihood analysis, which previous research has suggested provides better estimates of the number of factors than the principal components method (Edman, Danko, Andrade, McArdle, Foster, & Glipa, Reference Edman, Danko, Andrade, McArdle, Foster and Glipa1999).

Results

Table 2 shows the factor loadings for each item. Items with loadings of .45 or greater were considered to load on a particular factor. This cutoff was selected on the basis that this maximized factor loadings while minimizing cross-loading.

Table 2 Factor Loadings for each CES-D Item

Ten out of the 20 items that make up the CES-D loaded on the first factor, comprising 18.8 per cent of the variance explained. This loading suggests a lack of distinction between depressed affect items (sad, depressed, etc), and somatic-retardation items (restless sleep, appetite, etc). It appears that with regard to Filipino seafarers’ experience of depression, depressive affect and somatic complaints are not disentangled.

Five of 20 items that make up the CES-D loaded on the second factor, comprising 13.2 per cent of the variance explained. These items are a combination of interpersonal, somatic, and depressive affect items (Radloff, Reference Radloff1977). Notably, they all seem to focus on the more social aspects of depression. The Depressive Affect items (“I felt lonely”, “I thought my life had been a failure”) and the Somatic Item (“I talked less than usual), all appear to require a social context. This cluster of items seems to summon a performative relational aspect of depression, that the experience of depression of Filipinos was tied to other people.

Four out of 20 items loaded on the third factor of the CES-D structure, making up 11.3 per cent of the variance explained in the sample. This factor seems to focus on the positive, with Filipino seafarers endorsing items that may be indicative of how they are positively dealing with depression. Items pertaining to having a hopeful outlook, and perceiving themselves as equal to other people, are indicative of this factor. Notably, this factor is similar to the Positive affect dimension established by Radloff (Reference Radloff1977), suggesting a similarity of this dimension with a western sample.

One item, number 20 “I could not get ‘going’” did not load on any items with the cutoff used, although it loaded most strongly (0.411) on Factor 1. The lack of engagement with this item may reflect its colloquial nature, which may not cleanly translate across cultures.

Discussion

The findings of this study suggest that Filipinos’ conceptualization of depression has certain distinctions from a Western sample, when compared to the established factor structure of the CES-D. For Filipinos, Depression is made up of three factors, Factor I combining Depressed Affect and Somatic Retardation items; Factor II combines Depressed Affect, Somatic Retardation, with interpersonal items; and Factor III is made of up of positive affect items. Particularly interesting is the distinct makeup of the items of the first two factors, which provide information about how Filipinos understand depression.

Factor I contains 10 of the 20 items of the CES-D, and is a combination of depressed affect and somatic retardation items, suggesting that Filipinos do not make a distinction between feelings and body sensations, and instead integrate the two as one experience. Kuo (Reference Kuo1984) and Ying (Reference Ying1988) present similar findings in their study of Asian immigrant groups. This is also similar to the findings of Lee, Sunita, Byrne, Wong, Ho, Lee, and Lam (Reference Lee, Sunita, Byrne, Wong, Ho, Lee and Lam2008), who present a merged model of psychological and somatic distress in study of a Hong Kong adolescent sample.

Lee and colleagues discuss the argument of the mind body holism philosophy of Chinese medicine to explain this combined factor. Because of this belief, emotions are experienced as a fusion of physical and psychological sensations. Klienman (Reference Kleinman2004) points out that, in Chinese society, depression is expressed as a physical discomfort rather than in psychological symptoms. Another explanation for this amalgamation might be the collective sense of self among Asians. Given this, individual well-being takes a back seat, but physical complaints are relevant and valid because they are related to the individual's ability to function in the group (Ying, Reference Ying1988). As Lee and colleagues (Reference Lee, Sunita, Byrne, Wong, Ho, Lee and Lam2008) suggest, somatic symptoms are an appropriate way to communicate any distress to the group. A third argument relates to the distinct style of communication among Asians. Findings suggest that Asians have a high adherance to emotional self-control, and therefore a higher use of indirect language, and a less open communication style (Park & Kim, Reference Park and Kim2008). Asians tend to limit disclosure of personal information and expression of negative emotions. Based on this explanation, it might be inferred that even at the conceptual level, Filipinos combine physical and negative emotional symptoms of depression in order to observe a level of emotional self-control.

Filipino literature has investigated Filipino conceptualizations of psychological well-being. Sycip, Asis, and Luna's (Reference Sycip, Asis and Luna1993) study of several focused groups reveals that a dimension of this conceptualization was physical health. Paz (Reference Paz and Paz2008) studied the complex semantic network in diverse ethnolinguistic groups (EG) languages to determine how Filipino wellness is conceptualized. This study identifies several cognates related to the concept of wellness; among them are (a) the ability to breathe easily or loosely, and (b) a physical state of feeling light and easy. In other words, for Filipinos, psychological well-being is conceptually interrelated with physical well-being.

The second factor, made up of five items, presents an amalgamation of Interpersonal, Depressed Affect, and Somatic Complaints items. This combination is similar to one of the factors of the CES-D uncovered by Chokkanathan and Mohanty (2013) with an Indian sample. What is notable in the finding's of this study is that, even for the Depressed Affect and the Somatic Complaints items, there is an underlying abstraction of the interpersonal. For example, the Somatic Complaint item number 13, “I talk less than usual” and the Depressed Affect item number 14 “I felt lonely” both have a social connotation. This suggests that a relational dimension is deeply embedded in the Filipino concept of depression. In relation, it may suggest that Filipinos do not distinguish the internal (physical and psychological) self from the interpersonal.

De Guia (Reference de Guia2013) discusses the Filipino concept of kapwa, which is defined as the shared self or shared identity (p. 180) where the concept of self includes the other. Pe-Pua and Marcelino (Reference Pe-Pua and Protacio-Marcelino2000) refer to kapwa as a core term in Filipino Social Psychology, “at the heart of the structure of Filipino values” (p. 56). One category of kapwa is Hindi-Ibang-Tao or being one of us (Pe-Pua & Marcelino). The highest level of Hindi-Ibang-Tao is pakikiisa or being one with, which suggests that, at the core of a Filipino's being, it is essential that one feels intimately, emotionally connected. Bringing this argument forward, when one does not feel connected, one feels helpless or lost.

The results of this study suggest that there is a distinct conceptualization of depression among Filipinos and that there is a need to acknowledge this distinction. Doing so suggests several implications within the field of clinical psychology. First are implications on proper diagnosis of depression and depressive symptoms. The communication of physical distress, for example, may take on more meaning in the assessment of a Filipino sample. Relatedly, the de-emphasis on depressed affect should also be noted. A proper diagnostic inquiry for Filipinos should also include significant time or space on discussing the client's interpersonal context. As this study has shown, the interpersonal is very much integrated with psychological and physical well-being. The importance of the social aspect also carries implications in terms of appropriate counseling and intervention. This study suggests that counseling a Filipino should invariably include working with his social system as well.

It is important to be aware of two significant limitations in this study, both of which are based on the sample selection. First, this is a study of male participants. It is possible that the findings cannot be generalized to female Filipinos. Second, this is a study of seafarers. The literature on the seafaring experience suggests that this occupation is one of the most stressful professions because of long periods of separation from loved ones, harsh conditions, a monotonous routines, and danger from the possibility of piracy. It is possible that findings would be different given more variety in terms of participant employment.

Conclusion

Results from this study suggest that Filipinos appear to have a rather distinct conceptualization of depression, when compared to European-American samples. In particular, Filipinos do not differentiate depressed affect from somatic symptomatology, a finding similar to the conceptualization of other Asian groups. Furthermore, Filipinos also appear to imbed depression within a social context, an idea that can be explained by Filipino culture's interdependent conceptualization of the self. The present study further paves the way for the importance of interweaving culture in the discussions, research, and intervention of psychological well-being.