INTRODUCTION

Ethiopia used to be a textbook case of the intermingling of politics and (international) humanitarianism. Drought response examples from the 1970s and 1980s, involving forced displacements or the downfall of regimes, abound. De Waal (Reference de Waal2018: 140) characterised the drought of 1984 as a ‘second-degree famine crime’, as the controlling Dergue military regime ‘created and sustained the famine as part of its counter-insurgency’. De Waal detailed how the Ethiopian army looted villages and livestock, blocked roads and bombed markets, and requisitioned World Food Programme supplies to feed the militia. In multiple regions, international aid was instrumentalised to lure the population into ‘protected’ villages (Hagmann & Korf Reference Hagmann and Korf2012).

However, analyses of the politics of foreign aid flows are thinner regarding humanitarian issues concerning Ethiopian nationals, the less peripheral regions of the country and more recent events. A few exceptions are condemning human rights reports (Human Rights Watch 2010) and academic literature focusing on the politics of development issues (Bishop & Hilhorst Reference Bishop and Hilhorst2010; Cochrane & Tamiru Reference Cochrane and Tamiru2016), refugee care (Corbet et al. Reference Corbet, Ambrosetti, Bayle and Labzae2017) or the more openly conflict-ridden Somali region (Binet Reference Binet2011; Hagmann & Korf Reference Hagmann and Korf2012; Carruth Reference Carruth2016).

This article aims to rekindle the debate on the politics of humanitarianism in contemporary Ethiopia. Relief in Ethiopia is mainly geared towards disasters triggered by natural hazards. The country experienced major flooding in 2006 and droughts in 2002–2003, 2011 and 2015–2017. In 2016, 10.2 million people required international assistance (UN OCHA 2017). Responding to disasters is the remit of national government, with international humanitarian agencies playing an auxiliary role. Together, they face the resource shortages and logistical difficulties associated with supporting millions of food-insecure people across various agro-ecological zones within an overstressed and competitive global humanitarian landscape. Efforts to address these challenges have involved improved disaster risk profiling, early warning systems, drought-resistant farming practices and smoother aid procurement chains and cross-sectoral collaboration. The technocratic language of these interventions may give the impression that they are implemented in ‘ahistorical, apolitical and tabula rasa environments’, as Cochrane & Tamiru (Reference Cochrane and Tamiru2016: 652) observed for Ethiopian development programmes. In reality, power relations, questions of legitimacy and authority games always play a role, although this is less obvious than in the previous century. Today, the political is increasingly hidden in the mundane routines of everyday practice of relief programmes (Hilhorst Reference Hilhorst2013: 232) but can nonetheless have major implications for disaster-affected populations.

This is particularly true during accelerated political turmoil, as occurred in 2016 in Ethiopia, when the response to the worst drought in half a century (de Waal Reference de Waal2018: 136) coincided with a violent protest phase, the extrajudicial jailing of tens of thousands and the killing of hundreds, followed by the declaration of a state of emergency (SoE) in October (Abbink Reference Abbink2016; Amnesty International 2017). Focusing on a year of both hydro-meteorological and socio-political stress provides a much-needed reflection on the dynamics through which humanitarian response and political conflict interact (King & Mutter Reference King and Mutter2014). Moreover, although most conflict-related literature focuses on high-intensity conflicts, it is important to explore the much more frequently observed low-intensity conflicts (HIIK 2016; Human Security Report Project 2016), such as the 2015–2016 turmoil in Ethiopia.

This political turmoil occurred in the larger context of a restricted space for civil society, the implications of which are only starting to be problematised in the development and human rights literature (Hagmann & Reyntjens Reference Hagmann and Reyntjens2016). Possible repercussions for humanitarian response in terms of how organisations frame and enact humanitarian principles are still largely unknown. The study of the everyday politics of aid in Ethiopia, with its strong if not authoritarian government, is particularly interesting in light of the current global resurgence of state sovereignty affirmations (Cooley Reference Cooley2015), which result in a widening gap with the concurrently evolving understanding of international humanitarian mandates (Kahn & Cunningham Reference Kahn and Cunningham2013).

Keeping these broader implications in mind, this article examines how the relations between aid, state and societal actors affected the response to the 2016 drought in Ethiopia and which strategies actors developed to support disaster victims, given the context of protests and the declaration of a SoE. Here, the concept of ‘actors’ extends beyond the usual humanitarian suspects such as the United Nations (UN) or international non-governmental organisation (INGO) members, to include the realities and perceptions of government officials and Ethiopian non-governmental organisations (ENGOs). While our main focus is on the providers of aid, the paper has also drawn on insights of community members about these processes. A major finding of our research was how role playing and discursive games influenced the opening and closing of the humanitarian space where disaster response took place. To analyse our findings, we draw on Erving Goffman's (Reference Goffman1959) distinction between ‘frontstage’ and ‘backstage’ behaviour. We begin by presenting the theoretical and methodological foundations of our analysis and describing the Ethiopian context.

DISASTERS IN TIMES OF POLITICAL TURMOIL

As O'Keefe et al. (Reference O'Keefe, Westgate and Wisner1976) and many others (Blaikie et al. Reference Blaikie, Cannon, Davis and Wisner1994; Füssel Reference Füssel2007; Cannon & Müller-Mahn Reference Cannon and Müller-Mahn2010) have argued, disasters are not external natural events; rather, they are societally endogenous political processes. Who will be the most vulnerable to a natural hazard is socially shaped, as is who benefits from disaster response. Answers to these questions depend on who has the power to define and give meaning to the disaster event, to decide on pre- and post-disaster policy and effects, and to determine which resources will be allocated to which recovery and reconstruction efforts (Olson Reference Olson2000).

The concept of the humanitarian arena (Hilhorst & Jansen Reference Hilhorst and Jansen2010) provides a lens through which to capture these dynamics, asserting that aid is shaped by ‘aid–society relations’ in the sense that the actors along multiple aid chains, from ‘donor representatives, headquarters, state agents, local institutions, aid workers, [and] aid recipients … [to] surrounding actors’, are intrinsically embedded in the society where they operate (Hilhorst Reference Hilhorst2016: 5). As Hilhorst (Reference Hilhorst2016) further stressed, aid actors do not form a separate layer, but rather add to the complexity of governance, which is made up of government and a range of societal actors. All these actors are subject to multi-level power relations, with aid practices and their results remaining the outcome of ‘the messy interaction of social actors struggling, negotiating and at times guessing to further their own interests’ (Bakewell Reference Bakewell2000: 108–9).

As major disruptive events, disasters are likely to serve as catalysts, cracking open tensions looming close to the surface (Hutchison Reference Hutchison2014). Drury & Olson (Reference Drury and Olson1998) and Pelling & Dill (Reference Pelling and Dill2010: 15) highlighted the porosity of the conflict–disaster nexus, asserting that ‘disaster shocks open political space for the contestation or concentration of political power and the underlying distributions of rights between citizens and citizens and the state’. Disaster response then becomes one of the venues through which political issues play out, diminishing or increasing actors’ resources, legitimacy and, in effect, power. The apparent apolitical dimensions of disasters can provide a useful façade behind which to conceal the political manoeuvring processes of state, societal and humanitarian actors around aid flows. Still, a balanced view must be reached. Aid and disaster response are partly (hidden) politics, with the goal of furthering one's interests (or those of the funder), but they are not only a game of the ‘bigger forces’. Aid dynamics are complex, as aid acts as a ‘conduit between places and people, facilitating relief and reconstruction assistance as well as political legitimacy and, hence, the political and economic stability of a place’ (Kleinfeld Reference Kleinfeld2007: 170).

Disaster response in low-intensity conflicts

The ever-present politics of disaster becomes especially poignant in cases of conflict. That includes low-intensity conflict (LIC) settings, which are associated with relatively low numbers of casualties. LICs make up the largest share of conflict events and are globally on the rise (HIIK 2016; Human Security Report Project 2016). Ethiopia, where cycles of protests and state repression with linked sporadic outbursts of violence existed prior to the 2016 drought, can be considered a case of LIC. Azar's (Reference Azar1990) conceptualisation of protracted social conflict helps to grasp the source of these tensions: a disarticulation of state and society, whereby the institutional state is dominated by a single group or coalition perceived as unresponsive to the needs of other groups in society. In Ethiopia, until the political reforms initiated by the ruling party in 2018, it was the Tigray People's Liberation Front (later in coalition with other parties under the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front) which dominated the federal state and accorded ‘ethno-cultural communities’ the right to ‘self-determination and self-rule’ in the 1991 ethno-federalist Constitution (Maru Reference Maru2010: 39). In practice, the federal state became ‘stronger than any previous Ethiopian state’, ‘developed structures of central control and top-down rule’ and neglected ‘political liberties, respect for human rights and economic equality’ – with identity and ethnic group tensions, democratic deficit and conflict as corollaries (Aalen Reference Aalen2006; Abbink Reference Abbink2011: 596). In LIC settings marked by heightened (ethnic) polarisation, where ‘sometimes unrecognized or poorly understood forces can suddenly and often unexpectedly come into play’ (Karl 2005, cited in Kingsbury Reference Kingsbury2014: 352), disasters are especially likely to disrupt daily life and affect institutional change (Pelling & Dill Reference Pelling and Dill2010).

Although we would expect large-scale disaster events to lead to an immediate outcry for international aid, governments involved in LIC settings may have the opposite reaction, minimising the need for aid to keep ‘foreign influences’ out (Kinross Reference Kinross2004). Indeed, as the legitimacy of the state is already internally under threat (Ghani & Lockhart Reference Ghani and Lockhart2009), humanitarian actors’ access may be fraught by contradictions between a national government claiming sovereign control over the response and the desire of international agencies to safeguard a neutral and independent space for humanitarian action. Carving out an independent humanitarian space is even more difficult when the authoritarian state doubles as a ‘developmental state’, which derives its legitimacy from increasing capacities and achieving (economic) results (Mkandawire Reference Mkandawire2001). This applies to Ethiopia, where double-digit growth and infrastructure mega projects are pursued to reinforce the performance legitimacy of the government, rather than ‘political’ considerations such as democracy (Abbink Reference Abbink2011: 598). In disaster response terms, the developmental state translates into (the depiction of) an effective state-led system supporting all disaster victims, which makes it difficult for humanitarian actors to justify their ‘presence, access, and [independent] operational space’ beyond the channelling of funding (del Valle & Healy Reference del Valle and Healy2013: 189).

This last statement hints at the importance of framing and role-playing for actors to negotiate legitimacy and the power to decide and act. In a context where state and society are disarticulated, inadequate disaster response can quickly (further) delegitimise authorities as responsible or capable in the eyes of the population or the international community. Conversely, non-state actors such as political opposition parties can increase their legitimacy and, in turn, political support by criticising the state or even offering better aid provision (Flanigan Reference Flanigan2008). Lacking the ‘naturalized authority’ and coercive power which states can rely on to allocate resources or restrict other actors (Ferguson & Gupta Reference Ferguson and Gupta2002: 982), international agencies rather depend on soft power, financial means and persuasion to deliver their services (Beetham Reference Beetham2013: 270). The processes of persuasion, crediting and discrediting depend on successfully framing the disaster response as efficient and fair. A particular issue in LIC settings concerns the attention paid to minorities who may fall outside the scope of government care.

Given the importance of making a good impression, the politicisation of aid flows is largely hidden from sight in LIC settings. Actors’ room for manoeuvre is restricted not only by overt political actions, but also through everyday politics – the ‘quiet, mundane, and subtle expressions and acts that are rarely organized and direct’ (Hilhorst Reference Hilhorst2013: 232). Spatial and bureaucratic restrictions are more likely to obstruct access than the physical boundaries or violent actions that present barriers in high-intensity conflict settings (Matelski Reference Matelski2016; Corbet et al. Reference Corbet, Ambrosetti, Bayle and Labzae2017). Aid agencies often find themselves seeking compromise with the authorities. In a rare study of aid dynamics in authoritarian settings, in Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, del Valle and Hearly (Reference del Valle and Healy2013: 188) reflect on the ‘ambivalent and symbiotic relationships’ between humanitarian agencies and state power, characterised by ‘complexity that defies easy generalizations’.

The two spaces of the humanitarian theatre

Erving Goffman (Reference Goffman1959) introduced his dramaturgic perspective on organisations to bring out the performative behaviour of people and teams in interaction. This theory recalls the famous opening of William Shakespeare's ‘As you like it’: ‘All the world's a stage, And all the men and women merely players’. Goffman distinguishes the frontstage from the backstage. Frontstage, the team seeks to impress the audience with a total performance, where the décor, props, lights and spoken words all convey confirmative facts supporting the chosen image. Backstage, the actors remove the frontstage masks, following their various goals but also gossiping and strategizing about their next performance.

The frontstage/backstage perspective has obvious analytical shortcomings in the study of aid. Unlike the idea of actors staging a play before an audience, impressions come about through interaction, and the audiences play an active role and likewise strategise – attributing images to the actors that are hard to reverse (Hilhorst et al. Reference Hilhorst, Weijers and van Wessel2012). Moreover, the boundary between front- and backstage is porous; in the backstage, actors may likewise perform with the aim to change social reality. Especially with the internet and social media, the backstage is not only visible, but often turns into another performative platform. Goffman noted that his use of these concepts was more rhetorical than analytical, adding that the ‘claim that all the world's a stage is sufficiently commonplace for readers to be familiar with its limitations and tolerant of its presentation, knowing that at any time they will be able to demonstrate to themselves that it is not to be taken too seriously’ (Goffman Reference Goffman1959: 246). The dramaturgic perspective is nonetheless useful to highlight the discursive games and role-playing that are so central to the LIC scenario.

Tying together the concepts introduced above, our analysis is organised around two stages of the humanitarian theatre:

(1) The frontstage, where actors showcase their disaster response and dutifully play their roles of performing and coordinating aid with informed professionalism, using powerful maps, impressive websites and other props to confirm this image; and

(2) The backstage, where actors share their perceptions of how disaster response is actually shaped and carried out. Here, reflections on observed challenges and power relations come more easily to the fore. The same applies to actors’ hidden agendas – pushing for change that aligns with actors’ interests or the interests of those they represent, beyond strict humanitarian assistance.

While the front- and the backstage can be considered different worlds, they also influence each other. Actors may choose to bring backstage observations frontstage via advocacy, or otherwise use their insights to navigate restrictions. Here, Hilhorst's (Reference Hilhorst, Allen, Macdonald and Radice2018) concept of ‘ignorancy’ comes into play. Ignorancy recognises the naivety that aid actors sometimes display in the field as an expression of agency – a deliberate feigning of ignorance as a tactic to smoothen relations or appease certain political audiences. In some cases, displaying a lack of knowledge of the political is a pragmatic and conscious choice to gain the trust of authorities and access to certain areas. In this article, we are particularly interested in the questions of if and how actors strategise to act upon their backstage observations. A closer look at the interface between the front- and backstage spaces is thus integral to our analysis.

METHODOLOGY

The first author conducted four months of qualitative fieldwork (February–July 2017), and the second and third authors carried out additional research in July 2017 and April 2017 respectively. The case study is part of the ‘When disasters meet conflict’Footnote 1 research programme. In Ethiopia, the data collection involved a total of 190 study participants, 118 of whom participated in semi-structured interviews or focus group discussions focusing on disaster response, especially how decision making was shaped among different actors, as well as general and 2016-specific challenges and solutions.

Four periods of research outside of the capital provided in-depth insights. Two episodes of two-week fieldwork were conducted in areas where drought and primarily anti-government motivated unrest coincided in 2016 in the Oromiya and Amhara regions. One trip was made to the Somali region, accompanying donors visiting 2017 drought response sites, which allowed for direct observation of interactions between all actors of the aid chain. Finally, a visit was made to a district of the Amhara region impacted by the 2016 drought but only peripherally affected by the political unrest.

To preserve the participants’ confidentiality and safety in 2016 protest hotspots, community-level focus group discussions were held only during the latter two visits. Additional data were collected through observation and exchanges at community level, as well as during formal and informal meetings of NGO and international organisation (IO) staff members. Further, secondary sources including official humanitarian reports, press clippings and the transcripts of four interviews relating to humanitarian aid constraints conducted in 2015 by Corbet et al. (Reference Corbet, Ambrosetti, Bayle and Labzae2017) were analysed. All collected material was stored and analysed using the NVivo software package.

Table I gives an overview of the semi-structured interview participants by actor type. We included government officials from the lowest governance level, called the kebele, to the federal level. In line with the epistemological paradigm of critical realism and the interpretive approach (Summer & Tribe Reference Summer and Tribe2008: 58), we acknowledge that all statements relate back to the participants’ subjective framing of the disaster and of the LIC, the dynamics of which varied greatly by location, and their own motives in ‘performing’ in the research. Far from seeking to present the ‘truth’, hard facts and broad generalisations, we see divergences and diverse interpretations as integral to our findings.

Table I Overview of interviewees.

Discussing the sensitive topics of protests, the SoE and even some effects of drought (e.g. cholera outbreaks) was not without risk for the research participants. We addressed this by applying strict confidentiality rules (Chakravarty Reference Chakravarty2012; Matelski Reference Matelski2014). The confidentiality of individuals, institutions and localities was guaranteed, and local officials’ authorisation to conduct fieldwork in a particular location was always obtained. As much as possible, we maintained strict ethics of transparency, although we did, for instance, de-emphasise our interest in the political unrest in interviews with authorities.

In our interactions with community members and humanitarian actors, indicating interest in and knowledge of the political in a context where it is systematically backgrounded could increase trust and openness. However, it was necessary not to go too far, and we adapted our approach depending on the situation. Non-engaging questions on drought impacts, especially when beginning to discuss displacement and deaths, helped to gauge whether the researchers and participants were willing to move backstage or would continue to provide the ‘correct’ frontstage answers to ostensibly apolitical questions on disaster governance.Footnote 3 The humanitarian theatre concept thus served not only as an analytical device, but also as a methodological tool. The interviewee's and interviewer's positions in the theatre also varied across research settings. During the first days of local fieldwork, kebele officials liked to select the community participants themselves, with interviews often conducted adjacent to government compounds. Only after trust was established and the researchers were granted freedom of movement and selection did the community participants volunteer more critical reflections.

CONTEXT

‘If it is a choice between making this public and not receiving aid, then we can do without the aid’ (Sheperd 1985, cited in Keller Reference Keller1992: 610). This statement, made by an Ethiopian empire official to a UN representative during the 1973 famine, encapsulates the politicisation of disaster response in a country scarred by cycles of drought and civil unrest spanning three governance regimes. Following the imperial government's initial efforts to cover up the 1973 famine, the military regime (1974–1987) ‘seemed more interested in pursuing a political agenda of statist control rather than a strategy designed to achieve food security’ (Keller Reference Keller1992: 623). The military regime also instrumentalised humanitarian aid for its 1980s resettlement programme. The rebels, managing the drought response in areas they held in the northern part of the country, were accused of misusing humanitarian aid for war purposes (Gill Reference Gill2010). Ultimately, the failure to quickly recognise and respond to the 1973 and 1984 droughts contributed to the demise of both the imperial and the military regimes. In the 21st century, instances of interlinked mobility and food security considerations (Hammond Reference Hammond2011) and politically motivated food aid beneficiary selectionFootnote 4 (Cochrane & Tamiru Reference Cochrane and Tamiru2016) are still reported under the rule of a government coalition headed by the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), which defeated the military regime in 1991.

The EPRDF government came to power promising democratisation. As it submitted itself to a democratic vote for the third time in 2005, it appeared the opposition had won more seats than the ruling party expected. That same election night, the prime minister banned demonstrations and public meetings in urban areas, and the post-election demonstrations and violence left 193 civilians dead (Rakner et al. Reference Rakner, Menocal and Fritz2007; Aalen & Tronvoll Reference Aalen and Tronvoll2009).

The 2005 national elections marked a turning point in terms of democratisation and space for civil society, with many important repercussions for Ethiopian politics today. The 2010 national election, in which the EPRDF won all but two seats, was rated as ‘short of standards of a free and fair election’ (European Union Election Observation Missions 2010) and has been characterised as ‘re-establishing the one party state’ (Tronvoll Reference Tronvoll2011). The government has been regularly criticised for repressing human rights and persecuting journalists and political opposition leaders (Human Rights Watch 2010, 2013; Amnesty International 2012). Government control extends to grassroots level, with the local development armies network linked to the ruling party, monitoring the population with a ratio of one party observer to five residents. Aalen & Tronvoll (Reference Aalen and Tronvoll2009: 195) concluded that ‘the excessive clampdown on the political opposition and civil society, coupled with the launch of new and repressive laws and the expansion of local structures of control and coercion, all demonstrated that the outcome of the 2005 elections was not more democracy, but more authoritarianism’.

The restricted civil society space affected humanitarian actors’ work. Agencies working on disaster response are no longer under the supervision of the Disaster Prevention and Preparedness Commission, which manages all response processes, but of the administrative Charities and Societies Agency. A 2009 declaration of this Agency and follow-up amendments constrain the involvement of foreign-funded NGOs in human rights advocacy and restricts NGOs’ administrative expenses to a maximum of 30% of total budget, with vague interpretations of both what human rights advocacy is and what constitutes an administrative expense (International Centre for Non-Profit Law 2012). Moreover, reliance on international funding is restricted, leading many ENGOs to struggle for their survival in ‘intensive care units’ (i.e. operating in ‘emergency mode’, geared towards their own survival) instead of challenging the status quo (ENGO29, 12.6.2017 Int.). International humanitarian institutions are not exempted from this situation. In line with a longer tradition of high modernism (Hoben Reference Hoben, Leach and Mearns1996) and the associated concentration of power among the elites and bureaucracy, international humanitarian resources such as health support (Carruth Reference Carruth2016) and refugee care (Corbet et al. Reference Corbet, Ambrosetti, Bayle and Labzae2017) are increasingly funnelled through governmental institutions and staff. Corbet et al. (Reference Corbet, Ambrosetti, Bayle and Labzae2017) detail how this is closely related to practical restrictions (e.g. scarce business visas, suspicious and hierarchical working culture with threats of expulsion, government monitoring oriented around numbers and output), sub-quality operations and conformism.

The increasing restrictions on aid have not impeded the steady growth of the volume of aid directed towards Ethiopia. Fantini & Puddu (Reference Fantini, Puddu, Hagmann and Reyntjens2016) explain this with reference to the negotiation skills of ‘aid speak’-savvy Ethiopian elites, as well as overarching economic and geopolitical drivers. They point out how development donors ‘invoke[e] … the emergence of exceptional conditions – typically droughts, famines or displacement – to bypass conventional standards of democracy, accountability and transparency’ in Ethiopia (Fantini & Puddu Reference Fantini, Puddu, Hagmann and Reyntjens2016: 100).

Limiting space for civil society and political opposition reduces regime criticism and dissent, but it can also lead to particularly violent repression when resistance does occur. The 2015–2016 drought overlapped with the longest sustained and geographically most widespread protests since the start of the current regime. The protests were triggered by the intention of having an integrated urban master plan of Addis Ababa encroaching on the surrounding Oromia Zone, but built on deep-seated dissatisfaction with the current political arrangement (Abbink Reference Abbink2016). Particularly large and brutally repressed riots occurred in Oromiya at the end of 2015, and in Oromiya (again most intensively) and Amhara in summer 2016.

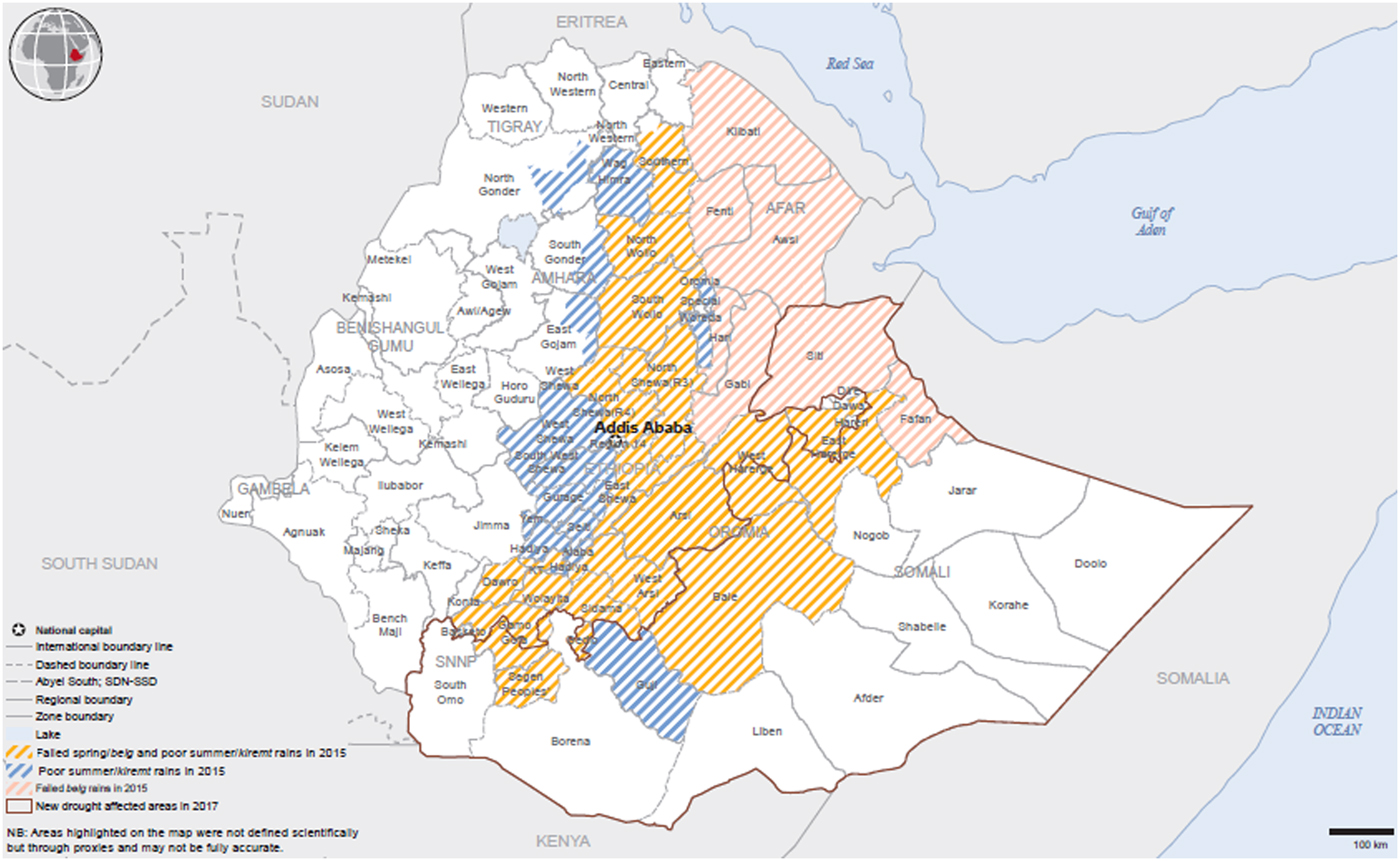

This was followed by the declaration of a 10-month SoE in October 2016, restricting the rights to assembly and information. Tens of thousands were jailed without formal legal proceedings, and hundreds were killed by security forces (Abbink Reference Abbink2016; Human Rights Watch 2016; Amnesty International 2017). Figures 1 (BBC 2016) and 2 (UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs [UN OCHA] 2017) show geographically that areas of the political unrest and the food insecurity that guided humanitarian action were thus largely overlapping. This does not signify a causal relation, but it did further test relations between aid, societal and government actors.

Figure 1 Protests and violence in 2015–2016 Ethiopia, as compiled based on internet and radio claims by the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED).

Figure 2 Areas affected by the 2015–2016 El Niño-induced droughts (dashed areas).

DISASTER RESPONSE PERFORMANCES AND EXPERIENCES IN THE HUMANITARIAN THEATRE

This section analyses how roles and power relations evolved in the governance of the humanitarian response to the 2016 drought, and how this was affected by political events, according to different actors.

Frontstage

We start our analysis with the frontstage, where the spotlights shine bright and humanitarian response comes across as especially well organised. The core tenet of the ‘Ethiopian humanitarian fairy-tale’ is efficient collaboration between diverse humanitarians and a proactively and financially highly engaged Ethiopian government (GoE), which reportedly contributed at least US$735 million to the 2015–2016 drought response (GoE & UN OCHA 2017). Different actors recount the story using similar words, as is shown by the following interview quotes from highly placed members of the GoE and an IO, and a statement made by an INGO member during a regional multi-actor meeting:

So what was the magic behind having 10 million people impacted, but no crisis? … [We have] a joint UN, government and INGO forum. All speak the same language! You might not see that in other countries. (Federal government official 1, 9.6.2017 Int.)

How do we decide who gets to be on the decision-making bodies? All country representatives of all humanitarian agencies are there; whoever is not present is not present, but that does not really happen here. Because of the nature of Ethiopia … Our approach, understanding of what coordination means, is to lead people to consensus … It is about providing the evidence, having trust to ensure that people feel comfortable and confident. (IO1, 2.3.2017 Int.)

We are not hiding. We are not fighting, competing, but work together to have water for the community. (INGO7, 9.3.2017 Int.)

According to these statements, the humanitarian model is not only efficient because of a high level of understanding between the actors, but also thanks to its clockwork-like organisation. As can be expected in a performance-oriented developmental state setting showcasing high capacities, processes are technical and systematised, as evident in interviews via the frequent naming of acronyms, institutionalised meeting platforms (e.g. the Strategic Multi-Agency Coordination Meeting and sector meetings co-chaired by a line ministry and associated UN organ), performance targets reached (dispatched trucks and quintals, number of beneficiaries listed in the bi-annual Humanitarian Requirements Documents, e.g. GoE & UN OCHA 2016) and codified processes. Concerning such processes, a key date on the humanitarian calendar is the belg assessment; around 200 staff members from the GoE, UN agencies, NGOs and donors are deployed throughout the country each June to assess the previous rainy season's (belg) performance. An intricate list of indicators (e.g. harvest expectations, market prices) then leads to the classification of districts, called woredas, according to three prioritisation levels that are neatly pictured in different tones of yellow to red on GoE/UN OCHA co-printed maps. Many respondents described this assessment process as technical and inclusive to all interested parties. The codification of processes can also be found at the local level. An ENGO staff member (24, 17.5.2017 Int.) started his interview with a detailed 14-step description of the disaster response process, from the ‘analysis by local NGO, woreda and zonal government staff’ to ‘the official launch when our NGO project gets the green light, together with the donor and line offices’.

All these processes add up to an intricately institutionalised response to food insecurity. The response follows a techno-logistic script; no negotiations are needed beyond settling logistical glitches, such as firing corrupt kebele government officials accused by higher-placed officials of causing gaps in the response (woreda government official 24, 8.6.2017 Int.; woreda government official 27, 9.6.2017 Int.). Moreover, there are few blind spots, as INGOs are presented as ‘hav[ing] eyes on the ground everywhere, wherever they have presence they can provide ground truth data’ (IO1, 2.3.2017 Int.). Strikingly, the script largely centres on IOs, the national government and funders. There is little space for community initiatives or most ENGOs, with the exception of ENGOs politically, administratively and financially affiliated to ruling parties. We approached one such ENGO in Amhara. It manages all governmental aid storage facilities in the region, and continued doing so throughout the protests (ENGO45, 8.6.2017 Int.; ENGO46, 17.6.2017 Int.). ENGOs were never named as drought responders without prompting. Following prompting, ENGOs were described as important, embedded and trusted by the communities, but their capacity was seen as too low to be part of the efficient system. An Oromiya zonal government official (2, 15.5.2017 Int.) described community members as not doing anything without government command.

Although all participants referred to consensus-based decision making, Ethiopian government officials usually described a government-centred system rather than a co-governed situation. A regional official, for instance, described the role of UN OCHA as ‘the secretaries at the forum … they take the minutes’ (1, 5.4.2017 Int.). An INGO member who had recently arrived in the country to manage emergency response operations (29, 25.3.2017 Int.) reflected on one of the official meetings she attended at regional level:

On one hand, strong government is good; they should own it. But as an INGO I feel we are being directed by government, and the UN as well. An [Ethiopian government official] said in one of the meetings where I was, ‘the UN is government’. So he does not see the difference. And in his opinion the NGOs are there to be told where to go, what to do.

Although this hierarchy is recognised by most non-state actors as well, it is not openly challenged. The central role of the government is considered legitimate, especially given the size and diversity of the country. A strong and engaged government prevents replication and makes it possible to feed over 20 million drought-impacted people.Footnote 5

Protests and the state of emergency

The protests and SoE played nearly no frontstage role. Strikingly, the protests were not mentioned in any of the weekly one-page Humanitarian Bulletin updates released during the most intense protest phase (June–September 2016). A first mention of the protests was made on 10 October, when the Bulletin directly cited the Federal Office's Attorney General in relation to the SoE (UN OCHA 2016b):

the rule of emergency was declared to restore order, ensure safety of the public and stability of the state. [According to the Attorney General,] ‘[t]he nature of recent violent demonstrations and conflicts that led to the loss of lives and destruction of properties make the State of Emergency crucial’.

On 24 October (UN OCHA 2016a), the Bulletin made another mention of this, stressing that humanitarian partners who continued to assist the government sought clarity on their role:

the Humanitarian Country Team seeks formal clarity on how the humanitarian response can continue amid restrictions stipulated in the State of Emergency on restriction of movement, designated ‘red zones’ and restricted freedom of assembly.

The subject was subsequently dropped again. According to all non-state participants, possible impacts of the protests and SoE were very rarely discussed in official meetings where government officials were present. At most, specific incidents such as attacked warehouses and trucks were mentioned, and these were not described as politically motivated or more taxing than the usual logistical difficulties: ‘There were reports of food not being dispatched quickly enough from warehouses. Does it happen every year? Yes it does … It is a complicated operation’ (IO1, 1.3.2017 Int.) As shown by the second Bulletin, the topic was raised only insofar as the protests and SoE would interfere with the techno-logistic script of the drought response.

Backstage

Moving behind the curtain, the contrast between the frontstage performance and the backstage governance of the drought response and the impacts of political turmoil, as described by the research participants, is striking.

Backstage, non-state participants emphasised government control rather than inclusive collaboration. Here, the ‘government-led response, with a quasi-Weberian iron cage of bureaucracy’ (IO8, 28.4.2017 Int.) was mentioned in more negative terms. Bureaucratic regulations combined with a lack of clarity make the GoE the major decision maker concerning, among other things, the timing and scale of the response (a GoE appeal to the international community is necessary) and the selection of activities, areas (permits must be granted) and beneficiaries.

Backstage, the effective capacity of the government, usually praised frontstage, was sometimes put in a different perspective. Community members in all visited areas, including the less LIC-affected Amhara woreda, mentioned widespread targeting ‘errors’ resulting in the exclusion of people lacking basic means from the aid distribution, or in the flat distribution of food aid, regardless of family size. Because of the seeming disorganisation of government officials in charge of distribution, we witnessed villagers waiting for days in the town to collect their (sometimes already spoiled) monthly aid supplies. An Amhara ENGO member (45, 8.6.2017 Int.) reported that disabled people, the elderly and lactating mothers had to pay helpers to bring them the food from the warehouse, as they could not go themselves.

Beyond mentioning these deviations from the ‘faultless’ techno-logistic script, backstage stories explicitly focused on the politicisation of the drought response. Rather than merely following the techno-logic, food aid quotas are up- or down-sized at different governance levels for political reasons, and corruption and people’s political affiliations reportedly come into play in local officials’ screening of beneficiaries. One highly placed IO officer noted that ‘our local staff is under a lot of government pressure’, ultimately reaching the conclusion that ‘targeting is an illusion invented by [the agency] and the government to please the donors’ (IO7, 27.4.2017 Int.).

These accounts contradict the technical, efficient and needs-based frontstage depictions of screening and distribution. Representatives of NGOs, community members and some IOs further lamented the lack of independence, on-the-ground monitoring and complaint mechanisms – in short, a disconnect between disaster response actors and the communities they want to help. The following quotes further highlight the limited independence of disaster response actors, which was also noticed by GoE officials and community members:

Ideally, the NGOs should bring up ground experiences to high levels … Here, NGOs can at most become contractors to do the work the government wants them to do. They are not really seen as partners or innovators; their potential is not used. (donor 2, 17.3.2017 Int.)

If INGOs had the chance to get direct contact with the community – that is my wish. Now the government is the one communicating and deciding. So there is a big chance in using that for other purposes. (Oromiya woreda government official 2, 12.5.2017 Int.)

Donors should participate in the activities we prefer. The contact to us should be direct. Without any interference. Now it is not direct contact. (Oromiya community member 1, 11.5.2017 Int.)

Linked to this issue of limited independence, the main challenge identified by respondents in the backstage area was not logistics but information – the lack of it, its distortion and its political use. An INGO member's (44, 25.5.2017 Int.) summary exemplified the statements of many: ‘Here, you can't give numbers without the government blessing. Information sharing is such a sensitive issue in Ethiopia. What you state should always be linked to a government source.’

Citing government sources is a difficult feat when numbers are hard to come by or to be trusted. For the 2015–2016 drought, ‘it took a long time for the government to really become transparent about [the] volume, size, and extent of the problem’ (donor 2, 17.3.2017 Int.). The historical taboos surrounding drought-induced death, displacement and outbreaks of diseases such as cholera also make obtaining information or programme authorisations difficult. Some agencies have to work for a drought impact to be recognised before starting to take action on it, or grapple with alternative terms, such as ‘acute watery diarrhoea’ for cholera. The associated challenges are numerous, impacting, among other things, fundraising, planning, and importing drugs that require special authorisation. The controversy around information was apparent in many interviews, where the frontstage and backstage of the drought response fused into frequently contradictory statements, such as in an interview with an Oromiya-based INGO official (38, 10.5.2017 Int.). Early on in the interview, in response to a question of whether his INGO conducted its own assessments, he replied, ‘We do not do our own. We support them, the government. It is better for us if we participate with them. The information from them is real.’ He then contradicted himself 30 minutes later, when asked to elaborate on the ideal shape of disaster response: ‘It would be better if [INGOs] did assessments. We receive reports only. Reading and seeing is a different thing. Also we should participate in monitoring. As it is now, we have too limited access.’

Protests and the state of emergency

The protests and SoE impacted the drought response much more than the frontstage performance suggests. A number of incidents occurred, such as attacks on aid transports, warehouses and government facilities, as well as government officials raiding NGO cars and preventing access. In Oromiya, where unrest would ‘happen every day in a new place, without possibilities to predict’, the situation was ‘very challenging’ (IO9, 30.5.2017 Int.), to the extent that some INGOs called their field staff back to Addis for a few days. One IO member also reported (IO9, 30.5.2017 Int.) that his agency had started planning with regional GoE authorities, keeping federal officials in the dark, for ways of dispatching aid other than via the government system (i.e. relying on more locally accepted ENGOs or civil society) in case the civil servants were kicked out and the people took control.

Our field visits further confirmed that the protests and SoE impacted drought response. In a protest-ridden district of the Amhara region, food distribution was suspended for one month (ENGO45, 8.6.2017 Int.). Stories of aid trucks set on fire and aid storage robbery attempts were reported in several woredas (ENGO46, 17.6.2017 Int.). In the visited Oromiya kebele, which was described as a conflict hotspot, drought response activities of the government (e.g. health posts, school feeding programmes) and NGOs (e.g. food aid distribution) halted as violence increased from both the population and the government. An INGO member described the summer months as ‘our hibernation’ (38, 10.5.217 Int.), imposed first because of security and then official access restrictions.

Many Oromiya respondents considered the SoE to have reduced violence and saved lives. However, although the SoE was considered to have enabled the drought response by increasing safety, it was also seen as having impeded the response, making access to certain areas, work permits and information more difficult. Information flows were interrupted by week-long internet outages and regular phone network outages (IRIN 2016). According to one foreign embassy official (donor 9, 21.4.2017 Int.) this happened because ‘there was some fear of people with a political mandate coming in the wake of humanitarian aid workers. That was basically seen as worse than having [a] big number of people helping the population.’

The interviews brought out that the impact of the protests and SoE were much more profound and political than mere logistical challenges. INGO representatives felt that they were inadvertently placed in the conflict. For example, when rioters burnt down a government grain storage facility, a neighbouring storage facility, managed by an INGO, was attacked and had grain stolen, although it was not burnt down. The government then assigned soldiers to protect the still-standing INGO warehouse. The INGO official telling this story (28, 23.3.2017 Int.) recalled, ‘We did not like that, because it would look like we were siding with the government. But at same time, we cannot take the soldiers off, because there is unrest and we must keep a good relationship.’

The direct involvement of NGOs was limited, and NGOs (without much debate) avoided acting on behalf of victims of political violence, mainly because these groups saw human rights issues as outside their mandate. Only one interviewed staff member and one driver at the same ENGO reported seeing it as their (personal) duty to assist wounded conflict victims. NGOs nonetheless became part of the politics. Some local participants expressed that the NGOs do ‘not need to come if they do not help fight the government’ (Oromiya community member 9, 15.5.2017 Int.). Government officials sometimes accused NGOs of supporting protesters. The aforementioned driver was even hit by a government representative while assisting a wounded woman.

The interviews also brought out how the drought response was instrumentalised to stop the protests. Areas and protesters were removed from beneficiary lists, and people were rewarded for not protesting or for informing on fellow community members, according to a woreda GoE official (2, 12.5.2017 Int.) reporting the words of a colleague: ‘If you calm down, we will support you again, even if you did something wrong about the government.’

There were also hints that the SoE affected civil society's capacity to deal with the drought. A community member with a higher position in the indigenous Gada Oromo governance system reported additional impacts on civil society (12, 15.5.2017 Int.):

When the unrest happened, we organised more. To support each other, amongst the tribe clans, the Gada system. Finding homes for the displaced, re-distributing food … but the Gada, after the declaration of the state of emergency, we had to stop, as we could not have meetings of more people.

Front- and backstage interfaces

The two sub-sections above have brought out the gaps between the frontstage stories and backstage experiences and narratives, which are summarised in Table II. In this section, we describe how non-state actors dealt with the contradictions between the frontstage and the backstage. The section only deals with non-state participants, because contradictions were extremely rarely acknowledged by Ethiopian state officials, along with the regret that there was nothing they could do about it (beyond ‘hidden strike’ levels of going about daily tasks, as mentioned by zonal government official 1, 22.5.2017 Int.). One of the aspects Goffman associated with the backstage is strategising to influence the frontstage performance.

Table II Main frontstage/backstage discrepancies.

Limited room for manoeuvre

Many interviewees had no answer to the question of how they would deal with their concerns articulated backstage. Interviewed community members all expressed powerlessness in that regard. The few possibilities aid actors mentioned consisted of dealing with the system without openly discussing concerns or challenging the government: carefully selecting the ethnicity of staff to be based in a field office or accompany field visits, maintaining parallel information databases and fighting GoE bureaucracy with evidence, numbers, detailed memoranda of understanding and donor guidelines, for various goals including being better informed or avoiding operating via government structures in a specific region. Agencies widely resorted to negotiating with the government within the dominant technical discourse, stressing supposedly objective facts and figures to adjust certain needs analyses and emphasising the common interest in helping communities. INGOs, for example, stressed that they could advocate for certain issues and excluded populations as long as they remained technical about it. Using indirect and unobtrusive tactics to influence the system required context-specific knowledge, negotiation skills and trusted contacts ranging from federal bureaucrats to kebele officials. Only one participant reported an example of a large donor that – behind the scenes – wrote a confidential protest letter to the government in relation to the blockage of aid during the SoE (INGO38, 10.5.2017 Int.).

Although silent diplomacy skills were important, independent action was constrained by many factors. Of paramount importance was information. Agencies usually had a limited presence on the ground and often lacked the whole picture. There were few venues to address issues apart from raising them with the government, even where the government was the source of concern. An Oromiya ENGO member (24, 17.5.2017 Int.) related how he had reported biased beneficiary screening to government line offices, although the bias came from government officials. To him, ‘that is the only route; we can't jump’.

Three forms of self-censorship

Although a number of factors limited the room for manoeuvre and independent humanitarian action, it became clear that agencies also played a role in these limitations through self-censorship. Three forms of self-censoring emerged as one of the only self-preservation strategies: self-censoring of words, actions and knowledge.

Speaking out openly for an independent humanitarian space was presented as impossible and too dangerous, especially for ENGOs. Self-censoring also took place as organisations framed problems as logistical even when they were ‘obviously’ political (INGO6, 6.3): ‘We cannot mention that the woreda government is not cooperative, but we can say that roads are bad.’ Instead of openly raising an issue, actors would mention 2016 conflict issues via less locally vulnerable actors, as was reported by an IO official (9, 30.5.2017 int.):

We could not release a statement here; it would jeopardise the situation. We had to send it to New York. If tried here, the anger and concern of the federal government … they would have said, let's shut down [the agency]. We had no choice. … [A higher official] raised the issue with the prime minister when he visited. So we have windows.

Self-censoring also happened in action and was often linked to actively suppressing knowledge. When the first author joined an NGO consortium on a monitoring field visit, they purposefully refrained from visiting a water pump site in a conflict area, ‘because then the government would know that we know’ (INGO7, 1.3.2017 Int.). Ignorancy is also seen in the re-framing of the humanitarian principles and mandates. Human rights issues especially are excluded from the mandate, despite the fact that they did hamper the effectiveness and impartiality of the humanitarian response in 2016. An INGO director (44, 25.5.2017 Int.) gave a surprising interpretation of the principle of neutrality, re-framed as ‘avoiding conflict areas’ in its programme. One ENGO member (16, 12.4.2017 Int.), when asked about drought-related mortality, stated that ‘death is none of my business’. We do not interpret this as actual ignorance about humanitarian principles. Rather, actors deliberately chose to narrow their scope and present themselves as innocent and ignorant enactors of the techno-logistic disaster response script, hence relying on ignorancy (Hilhorst Reference Hilhorst, Allen, Macdonald and Radice2018) as a strategic device.

Humanitarian attitudes towards independence

A final major finding from our interviews concerns the diverging attitudes of humanitarian participants concerning what should be done about the lack of independence of humanitarian aid. There was a common backstage acknowledgement of this situation: ‘The understanding of the humanitarian principles is smaller here [in Ethiopia]. Humanitarians here work on filling government gaps’ (ENGO23, 10.5.2017 Int.). Our participants recounted three narratives about whether this situation was problematic.

One group of participants, predominantly headquarter-based non-Ethiopian staff of the large and longer established IOs and INGOs, stayed closely within the remit of the frontstage narrative. As one IO representative said, ‘Disaster response here is an enormous logistical challenge, but not necessarily one where adherence to humanitarian principles is strictly necessary’ (IO8, 28.4.2017 Int.). These humanitarians were convinced that the GoE is basically doing a good job under difficult (landscape-dictated) circumstances, especially compared with the huge famines of the past and with neighbouring countries. They considered Ethiopia to be effectively operating and posing few challenges to humanitarians, viewed Ethiopia as an easy post, and were not bothered by the government's near-monopoly on information.

Another group of participants, working in both international and Ethiopian structures, acknowledged that there were problematic aspects to the drought response, but took a pragmatic view. They chose to balance the need for immediate response to the drought with the importance of good long-term relations with the government. They aimed to maximise room for manoeuvre by ‘playing the game’, as elaborated above. To them, keeping up the frontstage performance was part of a considered strategy of ‘ignorancy’.

A third group of participants, usually members of ENGOs, of the globally more advocacy-oriented INGOs, but also IO/INGO international staff members who only recently arrived in the country, was very critical of the lack of humanitarian independence, especially in view of the SoE:

Overall, humanitarian space is limited. And we partly limit it ourselves. It is usually the UN's role to push for the humanitarian space; they have that privilege. But in Ethiopia, it has developed to a situation that all think the government is more powerful, that you can't push, can't discuss. I felt last year, with the state of emergency and all, it would clearly have been the moment to take a stronger position. (IO11, 12.6.2017 Int.)

These participants accused larger INGOs, IOs and donors of giving up on humanitarian principles and only being concerned with maintaining good relations and ‘running their big machines’ in their oligarchic ‘country-club way of functioning’ (INGO45, 26.4.2017 Int.). According to these participants, geopolitical and financial incentives, such as the ‘war on terror’, silenced the humanitarian community, and long-time humanitarian leaders had slipped into a comfortable routine and lost their critical edge.

CONCLUSIONS

Our analysis, detailing humanitarian performances and experiences in the humanitarian theatre's two spaces and interfaces in Ethiopia, brought forward stark discrepancies between the frontstage, where state and aid actors showcase the response, and the backstage, where they reflect on challenges and strategies. On the frontstage, all actors agreed on the (hierarchical) co-governance of the drought response, largely ignoring the impacts of the political turmoil, whereas backstage, they were often concerned with the information and decision-making monopoly of the state, the politicisation of aid, and the consequences of the unrest and SoE. In 2016, the effectiveness and impartiality of the response to a 50-year drought was especially hampered. Although this cannot be generalised to Ethiopia overall and the GoE's (financial) efforts and leadership were largely successful, respondents of all backgrounds reported a lack of transparency and accountability, as well as cases of biased response and aid being instrumentalised to reward or punish drought victims.

Even more striking is how non-state actors behaved following their own observations of the frontstage/backstage gap. For all actors, especially civil society members and ENGOs, room for manoeuvre is extremely limited. The frontstage remains quiet, as disaster response actors dismiss open discussion or advocacy, choosing instead to rely on self-censorship and ignorancy. They follow a narrowly defined mandate and adhere to the techno-logistic script to keep helping drought victims. But even backstage, silence abounds. With a few exceptions internal to some organisations, it seems there is no collective conversation on where to draw the line between respecting the sovereignty of the government and the intrusion of humanitarian principles after conflict dynamics invade the humanitarian response.

Our analysis shows how the restricted space available to Ethiopian civil society impacted the humanitarian space, where humanitarians find the discretion to decide what needs to be addressed. Although it is common that the line between sovereignty and humanitarian space is hard to define and negotiate in practice, it was found that such decisions were rarely debated within or between agencies, and hence remained outside the scope of reflection and evaluation.

Our plea to rekindle the discussion of the politics of aid in LIC settings extends to scholarly work. It remains important to study what happens in Ethiopia, where diverse and not least ethnic conflict dynamics unfold and 1.4 million displaced people are in need of humanitarian assistance, notwithstanding the 2018 political reforms (International Displacement Monitoring Centre 2018). More research on this will also be relevant for the increasingly numerous authoritarian and LIC settings.