I. INTRODUCTION

Graphene is a single atom, thick two-dimensional (2D) material, thus, exhibiting ∼97.7% transmittance throughout the entire visible light spectrum. Additionally, graphene has a flat transmittance spectrum from the ultraviolet (UV) region to the long wave length infrared (IR) region, thus exhibiting a wide window that allows a comprehensive range of photon wave length passed through it. Unconditionally, except graphene, these combinations of remarkable optical properties are yet to be observed in any types of materials till date. Similarly, graphene has unusual electronic transport properties, which follows the characteristics of 2D Dirac fermions, quantum hall effects, Landau level quantization, and so on. Consequently, graphene's free charges are immobile in one spatial dimension but mobile in other two dimensions, and thus, charge carrier mobility is ∼106 cm2/V/s in free-standing graphene. Similarly, graphene also exhibits excellent mechanical and thermal properties (k ∼ 3000–5000 W/mK) Reference Balandin1 and chemical inertness. Hence, all these properties coupled with the optical properties put together graphene a stronger candidate for applications in transparent conducting electrodes (TCEs), flexible optoelectronics, energy-harvesting devices, photodetectors, and many other optical devices. Furthermore, graphene is anticipated as an emerging alternate for conventional transparent conductive metal oxides, specifically, indium tin oxide (ITO), which contains indium as a toxic, costly, and scarce element. In particular, the graphene-based TCE for application in solar cells with enhanced efficiency is of utmost interest.

To date, graphene electrodes have been applied for different types of solar cells, namely, solid-state solar cells, electrochemical solar cells, quantum dot solar cells (QDSCs), and polymer solar cells. The main advantages of applying graphene in different solar cells are: (i) it creates a window for inducing wide ranges (from UV to far IR regions) of photon energy inside the solar cells, (ii) it exhibits higher charge transfer (CT) kinetics at the interface of electrochemical hybrid cells, (iii) it manufactures a flexible device with robust architecture, and (iv) it provides greater heat dissipation. On the other hand, electrocatalytic activities of graphene play a key role in enhancing the efficiency of electrochemical solar cells like dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs), where the liquid/solid interface acts as a pathway for transferring electrons. However, the inert nature of the graphene basal plane often holds back CT at the graphene/liquid interface despite the high in-plane charge mobility, so enhancement in electrocatalytic activities occurs only through the edge-planes. Hence, surface functionalization of graphene is required to improve in-plane CT and enhance application for electrochemical solar cells.

II. AN OVERVIEW OF GRAPHENE SYNTHESIS

The basic building blocks of all the carbon nanostructures are single graphitic layers, which are covalently sp 2 bonded carbon atoms that exist in a hexagonal honeycomb lattice (Fig. 1), which forms 3D bulk graphite, when the layers of single honeycomb graphitic lattices are stacked and bonded by a weak van der Waals force. The single graphite layer, when forms a sphere is known as zero-dimensonal fullerene, when rolled up with respect to its axis forms a one-dimensional cylindrical structure, called the carbon nanotube, and when it exhibits a planar 2D structure from one to few layers stacked to each other, called graphene. Reference Geim and Novoselov2 One graphitic layer is known as single-layer graphene and correspondingly 2 and 3 graphitic layers are known as bilayer and trilayer graphene, respectively. More than 5 layers up to 10 layers graphene is generally called as few-layer graphene and ∼20 to 30 layered graphene is characterized as multilayer graphene or thick graphene or nanocrystalline thin graphite. Reference Das, Choi, Choi and Lee3

FIG. 1. The 2D hexagonal nanosheets of graphene as a building block of other forms of carbon nanomaterials. Reprinted with permission from Nature Publishing Group. Reference Geim and Novoselov2

This section overviews the major and most popular graphene synthesis process, including exfoliation, chemical synthesis, thermal chemical vapor deposition (CVD), and epitaxial growth together with a brief discussion of their feasibility for applications in solar energy devices.

A. Mechanical exfoliation

Mechanical exfoliation belongs to a top down method in nanotechnology, by which a longitudinal or transverse stress is generated on the surface of the layered materials using simple scotch tape or atomic force microscopy (AFM) tip to strip off a single layer or few layers from the material. Although, mechanical exfoliation methods were attempted earlier in the year 1999 using AFM tips, however the process was unsuccessful to produce a single atom thick graphene layer. Novoselov et al. Reference Novoselov, Geim, Morozov, Jiang, Zhang, Dubonos, Grigorieva and Firsov4 invented the special type of mechanical exfoliation process, by which they successfully synthesized a single atom thick graphene layer.

B. Chemical exfoliation

In chemical exfoliation process, alkali metal ions were used to intercalate the bulk graphite structure to separate out graphene layers followed by the dispersion in a solution. The main reasons for using alkali metals for intercalation reactions are as follows: (i) alkali metal ions can easily react with graphite and form intercalated structures, (ii) they also produce a series of intercalated compounds with different stoichiometric ratios of graphite to alkali metals, and (iii) alkali metals have their atomic radius smaller than the graphite interlayer distance and hence easily fit in the interlayer spacing during the intercalation reaction. The major types of alkali metal ions are Li, K, Na, Cs, and Na–K2 alloy, which are commonly used to intercalate graphite for the chemical exfoliation process. Reference Viculis, Mack and Kaner5 Furthermore, the by-product of the exfoliation reaction, KC8, undergoes an exothermic reaction when reacting with the aqueous solution of ethanol (CH3CH2OH) as per Eq. (1).

Similarly, chemical exfoliation of graphene also demonstrated using the simple sonication process followed by the dispersion in organic solvents. Reference Hernandez, Nicolosi, Lotya, Blighe, Sun, De, McGovern, Holland, Byrne, Gun'ko, Boland, Niraj, Duesberg, Krishnamurthy, Goodhue, Hutchison, Scardaci, Ferrari and Coleman6 Hernandez et al. Reference Hernandez, Nicolosi, Lotya, Blighe, Sun, De, McGovern, Holland, Byrne, Gun'ko, Boland, Niraj, Duesberg, Krishnamurthy, Goodhue, Hutchison, Scardaci, Ferrari and Coleman6 reported the exfoliation of pure graphite in N-methylpyrrolidone using a straightforward sonication process, which yields high-quality unoxidized monolayer graphene.

C. Chemical synthesis and functionalizations

Chemical synthesis of graphene consists of few steps including the oxidation of graphite, dispersion of the graphene-oxide layers in a solvent, and reducing it back to graphene. The oxidation of graphite is carried out using the Hummer's method by reacting graphite with sodium nitrite, sulfuric acid, and potassium permanganate. Reference Hummers and Offeman7 The objective of transforming graphite into graphite oxide (GO) is to increase the interlayer spacing larger than the pristine graphite. In this regard, the interlayer spacing varies proportionally to the degree of oxidation reaction of graphite. Hence, this oxidized graphite further facilitates the dispersion of graphene in appropriate solvents. Graphene oxide is generally dispersed in a polar liquid medium, such as dimethylformamide (DMF), N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), hexamethyl phosphoramide (HMPA), etc. After that, the dispersed GO is reduced back to graphene using dimethylhydrazine treatment at 80 °C for prolonged time. The homogeneity of GO dispersion strictly varies with the types of functional groups attached to graphene, which further hold back the graphene agglomeration in the solution. Thus, homogeneous dispersion causes the homogeneous reduction of GO with enhanced properties. Till date, several reports have been demonstrated on the application of GO for organic solar cells, Reference Li, Tu, Lin, Chen and Chhowalla8 DSSCs, Reference Hasin, Alpuche-Aviles and Wu9,Reference Roy-Mayhew, Bozym, Punckt and Aksay10 QDSCs, organic memory devices, Reference Li, Liu, Li, Wan, Neoh and Kang11 Li ion batteries, Reference Chen and Wang12 and many more. The primary advantages of the chemical synthesis process are low temperature and solution-based process, and therefore it possesses lots of flexibilities for scalability and direct synthesis of graphene film on various substrates. Additionally, in situ functionalization of graphene can be easily performed using this process for tuning of graphene's chemical and catalytic properties. However, the chemical synthesis process of graphene production has several shortcomings, such as (i) small yield, (ii) defective structure, and (iii) incomplete reduction of graphene, which readily degrade the graphene properties.

D. Thermal CVD process

Graphene can be synthesized on Ni and Cu using the CVD of hydrocarbon gases at high temperature in reduced atmospheric condition. In this process, Cu and Ni foils are used as substrates, where graphene deposition occurs on the surface of those transition metals due to the catalysis process. Several other metals such as Pt, Pd, Ru, Ir, Co, and Fe are also used as substrates for the deposition of graphene by CVD. Reference Wintterlin and Bocquet13 The process temperature was kept at ∼1000 °C (although several lower or higher temperature processes were reported as well) under reducing atmosphere (H2 atmosphere) Reference Das, Choi, Choi and Lee3,Reference Wassei, Mecklenburg, Torres, Fowler, Regan, Kaner and Weiller14 to decompose methane (CH4) and form graphene as per the following Eq. (2):

The process is versatile and scalable as the catalyzing process does not vary with the substrate size. Although large-scale graphene can be obtained by the CVD process, however, achieving large-scale homogeneous layer of graphene is still under challenge. Additionally, formation of grain boundaries and ripples in graphene during CVD processes causes defect formation in graphene. Hence, those defects create a major charge scattering and deteriorate graphene's electrical, thermal, and optical properties.

E. Epitaxial growth

The epitaxial growth process is performed for fabricating highly crystalline graphene onto single crystalline SiC substrates. Several reports demonstrated the growth of graphene through sublimation of Si from single-crystal 6H–SiC. Reference Berger, Song, Li, Li, Ogbazghi, Feng, Dai, Marchenkov, Conrad, First and de Heer15 The growth process includes the surface preparation using oxidation or H2 etching, followed by surface cleaning by bombarding electrons at 1000 °C at ∼10−10 Torr pressure under heat treatment at 1250–1450 °C for 1–20 min. This growth process is based on the Si sublimation mechanism at high temperature, which creates the anisotropy in graphene. Reference Hupalo, Conrad and Tringides16 Epitaxially grown graphene on SiC exhibits smaller and larger domain size based on the thermal decomposition method and different process parameters. Reference Emtsev, Bostwick, Horn, Jobst, Kellogg, Ley, McChesney, Ohta, Reshanov, Rohrl, Rotenberg, Schmid, Waldmann, Weber and Seyller17 Even, high-quality superior grade epitaxial graphene is obtained by this process, Reference de Heer, Berger, Wu, First, Conrad, Li, Li, Sprinkle, Hass, Sadowski, Potemski and Martinez18 however, the transfer of graphene from SiC to other substrates is difficult, and the process cost is too high. Therefore, these seriously restrict the epitaxially grown graphene for solar cell applications.

F. Graphene transfer

Graphene transfer is a primary process for fabricating the graphene-based photovoltaic devices since graphene is synthesized in a dispersed solution form or a thin film on metal foils. To date, numerous processes have been demonstrated to transfer graphene on other substrates such as glass or flexible substrates. Some popular methods of graphene transfer from a dispersed medium to a substrate are drop-casting, spin coating, Reference Kymakis, Stratakis, Stylianakis, Koudoumas and Fotakis19,Reference Becerril, Mao, Liu, Stoltenberg, Bao and Chen20 dip casting, Reference Becerril, Mao, Liu, Stoltenberg, Bao and Chen20,Reference Wang, Zhi and Mullen21 and electrophoretic deposition. Reference Chavez-Valdez, Shaffer and Boccaccini22 Additionally, few other methods, such as vacuum filtration, Reference Eda, Lin, Miller, Chen, Su and Chhowalla23 spraying, Reference Li, Muller, Gilje, Kaner and Wallace24 Langmuir–Blodgett assembly, Reference Cote, Kim and Huang25 and self-assembly methods, Reference Ishikawa, Bando, Wada, Kurokawa, Sandhu and Konagai26–Reference Kim, Cote, Kim, Yuan, Shull and Huang29 are capable of transferring graphene on various transparent and flexible substrates. On the other hand, the graphene transfer processes from metal foils to other substrates are the chemical transfer process, Reference Li, Cai, An, Kim, Nah, Yang, Piner, Velamakanni, Jung, Tutuc, Banerjee, Colombo and Ruoff30,Reference Das, Sudhagar, Verma, Song, Ito, Lee, Kang and Choi31 PDMS transfer process, Reference Li, Zhang, Yu, Wang, Wei, Wu, Cao, Li, Cheng, Zheng, Ruoff and Zhu32 hot press lamination process, Reference Verma, Das, Lahiri and Choi33 stamping process, Reference Wang, Kim, Seo, Park, Hong, Park and Heeger34 and roll-to-roll transfer process. Reference Bae, Kim, Lee, Xu, Park, Zheng, Balakrishnan, Lei, Kim, Song, Kim, Kim, Ozyilmaz, Ahn, Hong and Iijima35

G. Graphene as TCEs

In conventional TCEs, controlling resistivity is one of the challenging tasks, which crucially depends on the two material parameters of high carrier concentrations Reference Chen, Jang, Xiao, Ishigami and Fuhrer36,Reference Akturk and Goldsman37 and high carrier mobility. Reference Chen, Jang, Xiao, Ishigami and Fuhrer36 In practical, the conventional transparent conducting oxide (TCO) materials were possessing few demerits, such as complex structure, large band gap, and unavoidable charge scattering centers (arising from the presence of intrinsic dopants, defects, etc.), and were limiting their performance. In the context of searching highly TCEs with remarkable carrier mobility, monolayer graphene-based TCEs are becoming highly popular compared to conventional TCEs. The zero band gap property as well as carrier mobility (several orders higher than the traditional TCOs) offers wide applicability as TCEs in nanoelectronics. Furthermore, several simple and scalable techniques have been demonstrated for easy transfer of graphene on any polymer substrates, which is economically sound and technologically significant for flexible, transparent devices. Geim et al. reported that single-layer graphene exhibits ∼98% transparency and is the ever-reported transparent material found to date. However, transparency and sheet resistance decrease with increasing number of graphene layers as follows: bilayer graphene exhibits 95% transmittance and 1 KΩ/sq sheet resistance, trilayer graphene shows ∼92% transmittance and ∼700 Ω/sq sheet resistance, and four-layer graphene possesses ∼89% transmittance and ∼400 Ω/sq sheet resistance. Reference Li, Zhu, Cai, Borysiak, Han, Chen, Piner, Colombo and Ruoff38 Wang et al. demonstrated the transparent graphene electrodes with 80% transparency, which is demonstrated as a TCO of DSSCs. Verma et al. Reference Verma, Das, Lahiri and Choi33 reported the large-scale transfer of few layer graphene on polymer by using a simple hot press lamination method with 89% transparency. They demonstrated a simple and low cost hot press method, which was extended as large as 15 × 5 cm. Graphene on polymer film was utilized as anode for high-resolution flexible field emission (FE) devices, where the flexible graphene showed recoverable electrical properties with stretching. Similarly, Lahiri et al. Reference Lahiri, Verma and Choi39 also demonstrated the full transparent and flexible FE device comprised of both graphene-based cathode and anode. In this context, a roll-to-roll process has been demonstrated for the synthesis of large-scale (30 inch) graphene for touch screen applications. Bae et al. Reference Bae, Kim, Lee, Xu, Park, Zheng, Balakrishnan, Lei, Kim, Song, Kim, Kim, Ozyilmaz, Ahn, Hong and Iijima35 reported the transfer of single- to four-layer graphene film on a polymer with transparency of 97 to 90%, respectively. In the same report, it is found that the sheet resistance of the graphene film also varied from 275 to 50 Ω/sq for single- to four-layer graphene.

III. GRAPHENE FOR SOLAR CELLS

A. Graphene for solid-state solar cells

To date, few reports have been found for graphene used as junction materials in solid-state solar cells. Although graphene is a near-zero band-gap material, due to the high mobility and electrical conductivity of graphene, the junction of graphene/n-type semiconductor heterojunction can be considered as an efficient Schottky junction. It is worth mentioning here that the work-function difference between graphene and the n-type semiconductor should be sufficient enough to create a built-in potential as shown in Fig. 2(a). Figure 2(a) shows the band diagram illustrating the mechanism of a graphene/n-type Schottky junction solar cell with a built-in potential of (ϕG−ϕn-Si). In this context, graphene-Si Reference Li, Zhu, Wang, Cao, Wei, Li, Jia, Li, Li and Wu40 and graphene-single CdS nanowire (NW) Schottky junction solar cells Reference Ye, Dai, Dai, Shi, Liu, Wang, Fu, Peng, Wen, Chen, Liu and Qin41 have been reported so far.

FIG. 2. (a) The band diagram of a graphene/n-Si Schottky junction; (b) schematic illustration of the fabrication process of graphene/n-Si Schottky junction solar cells. Reprinted with permission from John Wiley and Sons. Reference Li, Zhu, Wang, Cao, Wei, Li, Jia, Li, Li and Wu40

Li et al. first reported the graphene/n-Si solar cell, and the device structure is shown in Fig. 2(b). First, they created a trench by photolithographic patterning followed by etching away the 300-nm SiO2 layers from a wafer. Metal contacts were prepared using sputter deposition of Ti/Pd/Ag and Au on the backside and on the frontside of n-Si, respectively [Fig. 2(b)]. A few-layer CVD graphene was transferred over the pattern to prepare the graphene/n-type Si Schottky junction. The solar cell devices show an open circuit voltage (V OC) of 0.42–0.48 V, and a short-circuit current density (J SC) of 4.0–6.5 mA/cm2 with a power conversion efficiency (PCE) of ∼1.5% under the standard condition: air mass (AM) 1.5 global (1.5G) illumination of 100 mW/cm2. Similarly, few other reports were found mentioning graphene/Si nanocrystal and graphene/Si nanopillar array Schottky junction solar cells, where the reported PCEs are about 0.02 and 1.96%, respectively. In the same report, Feng et al. demonstrated a method of efficiency improvement of the graphene/Si nanopillar array Schottky junction solar cells by p-type doping of graphene using HNO3 treatment. The p-type doped graphene Schottky junction solar cells showed efficiency up to 3.55% using different dopant concentrations. Miao et al. Reference Miao, Tongay, Petterson, Berke, Rinzler, Appleton and Hebard42 showed the enhancement of graphene/Si Schottky junction solar cell efficiency up to 8.6%, which is the highest reported graphene-based solid-state solar cell efficiency. Here graphene is doped with bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)amide (TFSA), which act as a hole dopant in graphene increasing its work function without changing its optical properties. Reference Tongay, Berke, Lemaitre, Nasrollahi, Tanner, Hebard and Appleton43 The doping-induced graphene's chemical potential shift causes the carrier density increase in graphene as well as increase in the device's built-in potential and, thus, improves the solar cell fill factor and PCE up to ∼8.6%. Reference Miao, Tongay, Petterson, Berke, Rinzler, Appleton and Hebard42 In this regard, Ye et al. Reference Ye, Dai, Dai, Shi, Liu, Wang, Fu, Peng, Wen, Chen, Liu and Qin41 reported a new type of Schottky junction solar cell using a junction of CdS NW and/or CdS nanobelt (NB) with graphene. Figure 3(a) represents the schematic of Schottky junction formation in graphene-CdS. The CdS NW and CdS NB were synthesized by the CVD method and transferred them onto a SiO2/Si substrate as shown in the device architecture in Fig. 3(b). The device shows a PCE up to 1.65% (under AM 1.5G illumination) with corresponding J SC, V OC, and fill factor (FF) of 275 pA, 0.15 V, and 40%, respectively.

FIG. 3. (a) Schematic representation of a graphene/CdS NW Schottky junction solar cell; (b) the band diagram of the graphene/CdS NW Schottky junction. Reprinted with permission from American Chemical Society. Reference Ye, Dai, Dai, Shi, Liu, Wang, Fu, Peng, Wen, Chen, Liu and Qin41

B. Graphene-based DSSCs

1. Dye-sensitized solar cells

The third generation photovoltaic devices including semiconductor quantum dots (SQD), Reference Mora-Seró and Bisquert44 organic photovoltaics (OPVs), Reference Kim, Lee, Coates, Moses, Nguyen, Dante and Heeger45 and DSSCs Reference Yella, Lee, Tsao, Yi, Chandiran, Nazeeruddin, Diau, Yeh, Zakeeruddin and Grätzel46 find great attention in the photovoltaic research community. These new categories of photovoltaic devices are also appropriate in roll-to-roll fabrication and yield short energy payback time. In this part, we summarized the state of art on novel graphene-based materials for third generation PVs research including DSSCs, QDSCs, and OPVs.

Recently, DSSCs receive significant attention as promising embodiments in photovoltaic technologies for producing renewable, clean, and affordable energy. The low cost and the utilization of nontoxic components identify the DSSC as an ideal photovoltaic concept for integrated “green” architectures. In DSSCs, light absorption and charge transport are separated with charge carrier generation taking place in the chemisorbed self-assembled monolayer of sensitizer molecules sandwiched between the semiconducting anatase TiO2 (photoelectrode) and an electrolyte acting as electron- and hole-conducting materials, respectively [Fig. 4(a)]. The photoexcitation of the molecular dye under irradiation leads to a rapid electron injection into the conduction band (CB) of a semiconductor (i.e., TiO2), followed by electron transfer to the photoelectrode, where the original state of the dye is regenerated by electron donation from the electrolyte. The collected electrons in the photoelectrode are transported through an external circuit to the counter electrode (CE), and the circuit is completed through regenerating the electrolyte at the CE. Reference Hagfeldt, Boschloo, Sun, Kloo and Pettersson47 Recently, research has accelerated on optimizing material counterparts (photoanodes, electrolytes, sensitizers, and CEs) to improve the efficiency and stability of DSSCs to bring into commercialization [Fig. 4(b)].

FIG. 4. (a) Schematic structure of DSSCs; (b) sandwich flexible DSC module. Reprinted with permission from American Chemical Society. Reference Hagfeldt, Boschloo, Sun, Kloo and Pettersson47

2. Graphene as photoanode

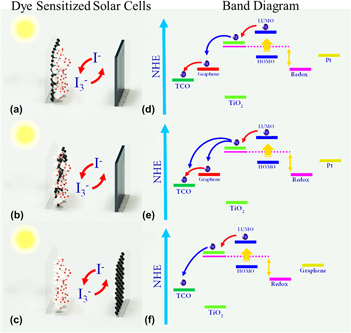

Over the last few years, graphene incited great deal of attention in DSSCs owing to their unique characteristics such as (i) rapid electron transport, (ii) exemplary light transmittance capability, and (iii) tunable electrochemical properties. Reference Das, Sudhagar, Verma, Song, Ito, Lee, Kang and Choi31,Reference Chen, Zhang, Liu and Li48–Reference Zhang, Zhao, Zhang, Chen and Qu51 A wide research has been conducted on graphene-based DSSCs, and they are categorized in Fig. 5. Reference Roy-Mayhew, Bozym, Punckt and Aksay10,Reference Wang, Zhi and Mullen21,Reference Kim, Yoo and Moon52–Reference Yang, Zhai, Wang, Chen and Jiang69 Wang et al. Reference Wang, Zhi and Mullen21 explored graphene as a high transmittance electrode material (97.7%), which is the maiden attempt that opened a new pathway for utilizing graphene in DSSCs [Fig. 5(a)]. In principle, the photoanode of a DSSC functions as an electron “vehicle” to transport the injected electrons from the excited dye sensitizers to the outer circuit. In this point of view, graphene is a promising composite candidate to TiO2, which markedly facilitates the electron transfer from TiO2 to a current collector Reference Song, Yin, Yang, Amaladass, Wu, Ye, Zhao, Deng, Zhang and Liu62,Reference Tang, Lee, Xu, Liu, Chen, He, Cao, Yuan, Song, Chen, Luo, Cheng, Zhang, Bello and Lee68,Reference Bell, Ng, Du, Coster, Smith and Amal70 [auxiliary transport indicated in blue color arrow in Fig. 5(b)]. The reason behind it is the band position of graphene [normal hydrogen electrode (NHE) ∼ −4.4 eV], which lies between the fluorine doped tin oxide (FTO) (NHE ∼ −4.7 eV) and TiO2 (NHE ∼ −4.2). Thus, it is anticipated that placing graphene in between FTO and TiO2 will offer an easy CT pathway to the photoanode. Reference Chen, Hu, Song, Guai and Li71 Compared to other 1D composite facilitator, spatially well dispersed graphene sheets extend high feasibility with nanocrystalline (TiO2) particles. Reference Tang and Hu72 Moreover, graphene acts as an auxiliary binder (0.8 wt%) in making crack-free TiO2 mesoporous thick films without compromising the photoconversion efficiency of the device. Reference Neo and Ouyang73

FIG. 5. Three different DSSCs of (a) graphene as TCO, (b) GT as anode, and (c) graphene as cathode. (d), (e), and (f) represent the corresponding band diagrams of DSSCs shown in (a), (b), and (c) respectively.

Varieties of techniques have been demonstrated in the fabrication of graphene-TiO2 (GT) composite. The GT composite can be synthesized either by: (i) graphene decorated on TiO2 framework Reference Sun, Gao and Liu74 [Fig. 6(a)] and/or (ii) in situ deposition of TiO2 nanoparticles (NPs) on graphene scaffold [Fig. 6(b)]. Reference Zhang, Li, Cui and Lin77,Reference Xin, Zhou, Wu, Yao and Liu78 By utilizing both presynthesized graphene matrix or TiO2 framework, the GT composite can be achieved through any one of the following techniques: hydrothermal, Reference Ding, Yu, Yuan, Liu and Fan79–Reference Sun, Zhao, Zhou and Liu83 electrophoretic deposition, Reference Chavez-Valdez, Shaffer and Boccaccini22,Reference Tang, Lee, Xu, Liu, Chen, He, Cao, Yuan, Song, Chen, Luo, Cheng, Zhang, Bello and Lee68 microwave-assisted, Reference Liu, Pan, Lv, Zhu, Lu, Sun and Sun84 spin coating, Reference Tsai, Chiou and Chen85 and electrospinning. Reference Peining, Nair, Shengjie, Shengyuan and Ramakrishna57,Reference Anish Madhavan, Kalluri, Chacko, Arun, Nagarajan, Subramanian, Sreekumaran Nair, Nair and Balakrishnan86–Reference Kim, Kim and Yang88 Mostly, the GT composite enhances the photocurrent density (J SC) of DSSCs compared to bare TiO2 electrode [Fig. 6(c)]. Reference Song, Yin, Yang, Amaladass, Wu, Ye, Zhao, Deng, Zhang and Liu89 Enhancement in J SC is attributed to (i) the optical scattering effect, which leads to red photon harvesting from solar spectrum and (ii) facilitated charge transport at TiO2/dye interfaces through graphene expressway, which promotes the charge collection at the photoanode. Reference Chen, Hu, Song, Guai and Li71 In literature, few articles reported that the GT composites enhance the J SC through lowering the charge recombination at TiO2/dye interfaces Reference Yang, Zhai, Wang, Chen and Jiang69 ; however, Durantini et al. Reference Durantini, Boix, Gervaldo, Morales, Otero, Bisquert and Barea90 confirmed that graphene does not shift the CB of TiO2 and neither influence the recombination process. Therefore, J SC enhancement is mostly associated with light absorption and scattering properties of graphene flakes in the visible region and auxiliary transport in addition to the TiO2 (graphene displays remarkably high electron mobility under ambient conditions ∼15,000 cm2/V/s). Nevertheless, one of the most critical factors in GT photoanode is the graphene composite quantity (wt%), which directly influences the PCE of the device. It is widely recognized that inclusion of graphene above the optimized wt% in TiO2 lowers the device performance. Though, graphene is known to be transparent in the wave length range of about 200–800 nm, however, more amount of graphene into the TiO2 matrix lowers the light availability for dye molecules, which ultimately decreases the light-harvesting contribution from dye sensitizers. On the other hand, overloading of graphene causes the reduction in the dye-loading amount of the GT electrode. Mostly, the narrow pore size of the GT electrode severely limits the dye-loading quantity. To overcome this issue, conventional 2D GT composite electrodes can be replaced with three dimensional (3D) wide pore graphene structure fabricated by using polystyrene inverse opals Reference Kim, Yoo and Moon52 and/or 3D nickel foam Reference Tang, Hu, Gao and Shi76 scaffolds. It is anticipated that these 3D GT electrodes offer both high dye loading and electrolyte diffusion. In 3D GT architectures, graphene was incorporated locally into the top layers of the inverse opal structures and then embedded into the TiO2 matrix via posttreatment of the TiO2 precursors [Fig. 6(d)].

FIG. 6. TEM images of GT composite prepared from different routes (a) graphene@TiO2; reprinted with permission from American Chemical Society. Reference Wang, Leonard and Hu75 (b) TiO2@graphene. Reference Bell, Ng, Du, Coster, Smith and Amal70 (c) A comparative photovoltaic performance of DSSC prepared with TiO2 and rGO/TiO2-based photoanode; reprinted with permission from John Wiley and Sons. Reference Song, Yin, Yang, Amaladass, Wu, Ye, Zhao, Deng, Zhang and Liu62 (d) SEM images of 3D GT composite using Ni foam; reprinted with permission from Elsevier Publisher. Reference Tang, Hu, Gao and Shi76

It is observed that the local arrangement of graphene sheets in 3D GT effectively enhances the electron transport without reducing light-harvesting contribution from dye molecules. Comparing 2D and 3D GT electrodes, it is found that 3D GT composite improves both J SC and V OC unlike 2D GT electrodes. The unprecedented V OC enhancement is ascribed to the high electrolyte diffusion at wide-pore natured photoanodes, Reference Han, Sudhagar, Song, Jeon, Mora-Sero, Fabregat-Santiago, Bisquert, Kang and Paik91 which ultimately enhances the energy transfer sites and lowers the recombination rate at TiO2/dye interfaces and thus supports high V OC in these devices.

3. Graphene as cathode materials

In DSSCs, CE is an essential constituent, which injects electrons into the electrolyte to catalyze triiodide reduction (

![]() ${\rm{I}}_{\rm{3}}^ -$

to I−) after charge injection from the photooxidized dye. The electrocatalytic reduction of

${\rm{I}}_{\rm{3}}^ -$

to I−) after charge injection from the photooxidized dye. The electrocatalytic reduction of

![]() ${\rm{I}}_{\rm{3}}^ -$

to I− at the CE [as shown in Eq. (3)] dictates the cathodic activity of DSSCs and influences current generation at the photoanode counterpart through dye regeneration.

Reference Gratzel92–Reference Wang, Anghel, Marsan, Ha, Pootrakulchote, Zakeeruddin and Gratzel96

${\rm{I}}_{\rm{3}}^ -$

to I− at the CE [as shown in Eq. (3)] dictates the cathodic activity of DSSCs and influences current generation at the photoanode counterpart through dye regeneration.

Reference Gratzel92–Reference Wang, Anghel, Marsan, Ha, Pootrakulchote, Zakeeruddin and Gratzel96

Platinum (Pt) is widely used as CEs for DSSCs owing to its excellent catalytic activity and low resistance. However, due to high cost, low abundance, and low chemical inertness, replacing Pt with other materials is becoming a fundamental issue for DSSCs. So far, it has been reported that different forms of carbon materials are quite stable and best alternatives for Pt CEs in DSSCs. Reference Murakami, Ito, Wang, Nazeeruddin, Bessho, Cesar, Liska, Humphry-Baker, Comte, Pechy and Graetzel97 In this context, graphene has several advantages for being a potential CE material for solar cells: high electrical conductance, high thermal conductivity, ultrahigh transmittance, and excellent mechanical properties. In particular, graphene exhibited remarkable transparency in the entire solar spectrum including IR region. Therefore, graphene CEs are quite advantageous for those types of solar cells/tandem solar cells, which need to absorb the entire range of photon energies (from UV-visible to IR) to generate excitons efficiently. Reference Wang, Zhi and Mullen21,Reference Verma, Das, Lahiri and Choi33,Reference Reina, Jia, Ho, Nezich, Son, Bulovic, Dresselhaus and Kong98,Reference Acik, Lee, Mattevi, Chhowalla, Cho and Chabal99 Furthermore, the high surface area of a 2D graphene sheet (2630 m2/g), in addition to its intrinsic high transmittance and charge mobility, offers greater versatility as a CE in DSSCs.

Hasin et al.

Reference Hasin, Alpuche-Aviles and Wu9

first reported the triiodide reduction capability of graphene and, thus, demonstrated the wide possibilities for applications in DSSC CEs. The report also showed that the surface functionalization by cationic polymer is one of the promising ways to increase the electrocatalytic property of graphene films, which has numerous advantages over improving DSSC efficiency. Kavan et al.

Reference Kavan, Yum and Gratzel100

demonstrated the graphene nanoplatelet-based DSSC CE as an optically transparent cathode, which is electrocatalytically active for the

![]() ${\rm{I}}_{\rm{3}}^ -$

/I− redox reaction. They fabricated the graphene-based cathode using a drop-cast method, and the device showed a PCE of about 5%. Roy-Mayhew et al.

Reference Roy-Mayhew, Bozym, Punckt and Aksay10

demonstrated the functionalized graphene sheet as DSSC CE with a PCE of 3.83%. They demonstrated the enhancement of electrocatalytic activity of graphene by functionalizing it using poly(ethylene-oxide)-poly(propylene-oxide)-poly(ethylene-oxide) triblock copolymer. In this context, Das et al.

Reference Das, Sudhagar, Verma, Song, Ito, Lee, Kang and Choi31

showed the functionalization of large-scale CVD graphene using fluorine (F− ions) ions with higher catalytic activity toward triiodide reduction compared to pristine graphene. The PCE of the DSSC showed ∼2.56% with corresponding V

OC, J

SC, and FF of 0.66 mV, 10.9 mA/cm2, and 35.9% respectively [Figs. 7(j)–7(n)].

Reference Das, Sudhagar, Verma, Song, Ito, Lee, Kang and Choi31

Similarly, HNO3-doped graphene showed an enhancement in the electrocatalytic activities of graphene with a DSSC efficiency of ∼3.21% as shown in Figs. 7(f)–7(i). The cell performance is lower than that expected, and this is due to the lower FF, which causes potential voltage drop at the graphene/FTO interface. Therefore, it has been well demonstrated that functionalized graphene is more effective than pristine graphene to enhance the kinetics of

${\rm{I}}_{\rm{3}}^ -$

/I− redox reaction. They fabricated the graphene-based cathode using a drop-cast method, and the device showed a PCE of about 5%. Roy-Mayhew et al.

Reference Roy-Mayhew, Bozym, Punckt and Aksay10

demonstrated the functionalized graphene sheet as DSSC CE with a PCE of 3.83%. They demonstrated the enhancement of electrocatalytic activity of graphene by functionalizing it using poly(ethylene-oxide)-poly(propylene-oxide)-poly(ethylene-oxide) triblock copolymer. In this context, Das et al.

Reference Das, Sudhagar, Verma, Song, Ito, Lee, Kang and Choi31

showed the functionalization of large-scale CVD graphene using fluorine (F− ions) ions with higher catalytic activity toward triiodide reduction compared to pristine graphene. The PCE of the DSSC showed ∼2.56% with corresponding V

OC, J

SC, and FF of 0.66 mV, 10.9 mA/cm2, and 35.9% respectively [Figs. 7(j)–7(n)].

Reference Das, Sudhagar, Verma, Song, Ito, Lee, Kang and Choi31

Similarly, HNO3-doped graphene showed an enhancement in the electrocatalytic activities of graphene with a DSSC efficiency of ∼3.21% as shown in Figs. 7(f)–7(i). The cell performance is lower than that expected, and this is due to the lower FF, which causes potential voltage drop at the graphene/FTO interface. Therefore, it has been well demonstrated that functionalized graphene is more effective than pristine graphene to enhance the kinetics of

![]() ${\rm{I}}_{\rm{3}}^ -$

reduction at cathode. As described in Reference Chavez-Valdez, Shaffer and BoccacciniRef. 54, graphene's electrocatalytic activity strongly varies with its defect concentration and oxygen-containing functional groups as shown in Fig. 8. Similarly, electro-catalytic activities of graphene are also associated with its active sites, which play a key role in CT at the interface. Few reports showed that the attachment of other functional groups such as –COOH, –CO, –NHCO– in graphene effectively improves graphene's electronic as well as electrocatalytic properties.

Reference Das, Sudhagar, Ito, Lee, Nagarajan, Lee, Kang and Choi102,Reference Xu, Li, Wang, Wang, Wan, Li, Zhang, Shang and Yang103

${\rm{I}}_{\rm{3}}^ -$

reduction at cathode. As described in Reference Chavez-Valdez, Shaffer and BoccacciniRef. 54, graphene's electrocatalytic activity strongly varies with its defect concentration and oxygen-containing functional groups as shown in Fig. 8. Similarly, electro-catalytic activities of graphene are also associated with its active sites, which play a key role in CT at the interface. Few reports showed that the attachment of other functional groups such as –COOH, –CO, –NHCO– in graphene effectively improves graphene's electronic as well as electrocatalytic properties.

Reference Das, Sudhagar, Ito, Lee, Nagarajan, Lee, Kang and Choi102,Reference Xu, Li, Wang, Wang, Wan, Li, Zhang, Shang and Yang103

FIG. 7. Graphene synergistic CEs for DSSCs. (a–e) graphene–CoS hybrid electrodes; reprinted with permission from Elsevier Publisher. Reference Das, Sudhagar, Nagarajan, Ito, Lee, Kang and Choi101 (f–i) HNO3-doped graphene; reprinted with permission from Royal Society of Chemistry. Reference Das, Sudhagar, Ito, Lee, Nagarajan, Lee, Kang and Choi102 (j–n) Fluorine-doped graphene; reprinted with permission from John Wiley and Sons Publisher. Reference Das, Sudhagar, Verma, Song, Ito, Lee, Kang and Choi31

FIG. 8. (a) and (b) schematic illustrating the attachment of the functional groups in graphene and the incorporation of defects on functionalized graphene sheets. Epoxides and hydroxyls are at the sides of the graphene plane, whereas carbonyl and hydroxyl groups are at the edges (gray atoms: carbon; red atoms: oxygen; and white atoms: hydrogen). Reprinted with permission from American Chemical Society. Reference Roy-Mayhew, Bozym, Punckt and Aksay10

Recently, Xue et al. proposed a new graphene-based 3D architecture for DSSC CEs as illustrated in Fig. 9. In this report, 3D graphene oxide foam is doped with nitrogen and used as a CE of DSSC, which showed a PCE of 7.07%.

FIG. 9. (a) Picture showing the synthesis of N-doped 3D graphene foam and transfer it for DSSC CE; (b) and (c) schematic illustrating the assembly of DSSC using N-doped 3D graphene foam and triiodide reduction process at the CE. Reprinted with permission from John Wiley and Sons. Reference Xue, Liu, Chen, Wang, Li, Qu and Dai104

Likewise, graphene embedded with polymer materials also showed promises for electrocatalytic cathode for DSSC. Several conducting polymers like, poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(styrene sulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS), polyaniline (PANI) have been used to enhance the electrocatalytic activities as well as the conductivity of the graphene/polymer composite. Hong et al. Reference Hong, Xu, Lu, Li and Shi105 reported the PEDOT:PSS/graphene composite CE for DSSCs with 4.5% PCE. In this work, they demonstrated the increment of J SC of DSSC after addition of a small amount of graphene in PEDOT-PSS, which was attributed to the higher catalyzing ability of graphene for iodine reduction at the CE. Reference Hong, Xu, Lu, Li and Shi105 Similarly, the graphene/PEDOT composite flexible electrode was demonstrated by Lee et al. Reference Lee, Lee, Lee, Ahn and Park106 In their report, they fabricated the graphene/PEDOT CE on the flexible PET substrate and assembled as DSSC.

The PCE of DSSC without TCO and Pt is 6.26%, which is almost comparable to DSSC with TCO and Pt (∼6.68%). Reference Lee, Lee, Lee, Ahn and Park106 Similarly, MnO2-PANI/r-GO composite showed a PCE of ∼6.15% with V OC, J SC, and FF of about 0.74 mV, 12.88 mA/cm2, and 65% respectively. One recent approach showed that the polydiallyldimethylammonium chloride/graphene oxide (PDDA/graphene) composite was used as DSSC CE with ∼9.5% PCE. In this report, Xu et al. fabricated the cationic polymer (PDDA) decorated on negatively charged graphene oxide (GO) by the layer-by-layer assembly method and found enhanced catalytic activity of GO due to the charge disparity between the electronegative carbon atoms and the nitrogen of ammonium ions.

On the other hand graphene/NP composite electrodes stipulate the research based on composite cathode toward high-efficiency DSSC. In this course of research, NPs anchored with graphene has also been demonstrated as a composite CE for DSSCs. Pt NP-anchored graphene was demonstrated for enhancing graphene's electrocatalytic activity for triiodide reduction in DSSCs. Reference Bajpai, Roy, Kumar, Bajpai, Kulshrestha, Rafiee, Koratkar and Misra63,Reference Gong, Wang and Wang107,Reference Li, Chen, Chen, Wang, Hao, Liu, He and Zhang108 The goal of these studies was to reduce Pt loading in DSSC CE by incorporating Pt/graphene composite electrodes without affecting its PCE. In this context, one report was found based on graphene/Ag NW composite electrodes with a PCE of 1.61%. Reference Al-Mamun, Kim, Sung, Lee and Kim109 Nonmetallic NPs such as CoS, NiO, Ni12P5, and TiN have been used to fabricate graphene-based composite electrodes. Reference Das, Sudhagar, Nagarajan, Ito, Lee, Kang and Choi101,Reference Bajpai, Roy, Koratkar and Misra110–Reference Wen, Cui, Pu, Mao, Yu, Feng and Chen112 CVD graphene/CoS composite electrodes showed a PCE of 3.42% with V OC, J SC, and FF of ∼0.72 V, ∼13.0 mA/cm2, and 36.40%, respectively. Reference Das, Sudhagar, Nagarajan, Ito, Lee, Kang and Choi101 Das et al. Reference Das, Sudhagar, Nagarajan, Ito, Lee, Kang and Choi101 demonstrated that implantation of CoS NPs on graphene enhanced catalytic activities of the composite electrodes due to the formation of catalytically active triple junction sites, which further facilitates the CT reactions at the DSSC cathode [Figs. 7(a)–7(e)]. Similarly, Wen et al. Reference Wen, Cui, Pu, Mao, Yu, Feng and Chen112 showed the graphene/TiN NP composite electrodes for effective DSSC cathode with a PCE up to 5.78%. On the other hand, graphene/CNTs also showed high promises as catalytic electrodes for triiodide reduction in DSSCs, hence, demonstrated in recent reports. Reference Choi, Kim, Hwang, Kang, Jung and Jeon113–Reference Zhu, Pan, Lu, Xu and Sun115 Table I lists the details about the performances of DSSCs based on graphene and graphene-derived CE.

TABLE I. Characteristics of DSSCs based on graphene CEs.

C. Graphene-based quantum dot-sensitized solar cells

Apart from DSSCs, semiconductor quantum dots (QDs) as light absorbing materials in QD-sensitized solar cells (QDSSC) also awake great interest by their fascinating features. In view of tuning the absorption spectrum of semiconductor QDs, Reference Kamat126 probing the particle size is an efficient way to harvest the entire range of the solar spectrum. Reference Smith and Nie127 In addition, owing to the unique electronic band structure, QDs can overcome the Shockley–Queisser limit of energy conversion efficiency. Reference Tisdale, Williams, Timp, Norris, Aydil and Zhu128 The ability of QDs to harvest hot electrons and to generate multiple carriers makes them a viable candidate for light-harvesting sensitizers in solar cells. Reference Semonin, Luther, Choi, Chen, Gao, Nozik and Beard129 Several semiconductor materials (CdS, CdSe, PbS, etc.) Reference Farrow and Kamat130–Reference Zhou, Yang, Huang, Wu, Luo, Li and Meng135 have been used as light sensitizers on wide band gap mesoporous metal oxide layers (TiO2 and ZnO) due to their low cost and simple sensitization processing. The device function of QDSCs is analogous to DSSCs [Fig. 10(a)], where the dye molecules are replaced with semiconductor QDs.

FIG. 10. (a) Schematic of CT at QD-sensitized TiO2 interfaces; reprinted with permission from American Chemical Society. Reference Mora-Seró and Bisquert44 (b) Comparing CT times for the DSSC (top) and SSSC (bottom); reprinted with permission from American Chemical Society. Reference Hodes136 (c) Fabrication of the layered graphene/QDs on ITO glass. (d) Cross-sectional SEM image of QD assembly in between the conformal graphene layers Reference Guo, Yang, Sheng, Lu, Song and Li137 ; reprinted with permission from John Wiley and Sons. Reference Guo, Yang, Sheng, Lu, Song and Li137 (e) Schematic structure of QD-assembled graphene as anode layer in QDSCs. Reference Sun, Gao, Liu and Sun138 (f) TEM images of CdSe QD-decorated graphene matrix. (g) CdSe QD/graphene JV performance in QDSCs; reprinted with permission from American Institute of Physics. Reference Sun, Gao, Liu and Sun138

Besides, the theoretical efficiency of QDSCs is as high as 44%, the practical performance still lags behind that of DSSCs at present. Reference Mora-Seró, Giménez, Fabregat-Santiago, Gómez, Shen, Toyoda and Bisquert139 Hodes Reference Hodes136 exclusively compared the critical factors of QDSCs to answer the question, why it is inferior to DSSCs. The main issues in QDSCs are (i) fast electron recombination at surface states of the TiO2/QD junction ascribed to a slower electron injection rate from QDs to TiO2 [Fig. 10(b)] and (ii) hole trapping between QDs. To achieve competitive photoconversion efficiency with DSSCs, the above factors have to be bottlenecked in QDSCs. In the context of promoting QDSC performance, different approaches were demonstrated—doping anode, Reference Lee, Son, Ahn, Shin, Kim, Hwang, Ko, Sul, Han and Park140,Reference Sudhagar, Asokan, Ito and Kang141 shell layer, Reference Tachan, Hod, Shalom, Grinis and Zaban142 QD passivation, Reference De La Fuente, Sánchez, González-Pedro, Boix, Mhaisalkar, Rincón, Bisquert and Mora-Seró143 hierarchical photoanodes, Reference Han, Sudhagar, Song, Jeon, Mora-Sero, Fabregat-Santiago, Bisquert, Kang and Paik91 Pt-free CEs, Reference Sudhagar, Ramasamy, Cho, Lee and Kang144 panchromatic sensitizers, Reference Braga, Giménez, Concina, Vomiero and Mora-Seró145 etc. However, graphene has attracted growing interest as a potential candidate for improving QDSC performance. Guo et al. Reference Guo, Yang, Sheng, Lu, Song and Li137 first demonstrated the feasibility of QD-decorated graphene [Fig. 10(c)] as photoelectrode, which showed best incident photon to converted electron (IPCE) compared to QD-decorated CNT scaffold. This confirms graphene as a good candidate for the collection and transport of photogenerated charges, and thus, the layered nanofilm [Fig. 10(d)] provides a new and promising direction toward developing high-performance light-harvesting devices for the next generation solar cells. Following that another interesting approach has been laid, where QD-decorated graphene has been applied as a photoanode in QDSC configuration [Figs. 10(e) and 10(f)] resulting in higher photocurrent than individual counterparts of graphene and QD-based device. Reference Sun, Gao, Liu and Sun138 This result suggests that the graphene network could serve as a good conducting scaffold to capture and transport photo-induced charge carriers. In addition, the work function of graphene is lower than the CB of QD CdSe offering energetic arrangement, which favors the photoinduced electron efficiently and transfers from excited CdSe to graphene. Therefore, an excellent conductive network of graphene with large electron transfer rates was obtained to extend electron mean free paths and escape charge recombination, ensuring that electrons can be collected effectively by the TCO substrate to produce photocurrent. Similar phenomena of capturing and transporting electrons from CdS QDs to TCO are realized in graphene compared to other carbon nanostructures. Reference Zhao, Wu, Yu, Zhang, Lan and Lin146

Although QD-decorated few-layer graphene matrix [Figs. 10(c) and 10(d)] showed good QD–graphene contact, the effective loading of the QD sensitizer is limited to a few monolayers. Therefore, careful control of graphene loading is required to extend QD films into the third dimension, where an essential balance must exist between maximizing contact with QDs while minimizing incident light absorption by graphene, which absorbs ∼2% of the incident light per monolayer. Lightcap and Kamat Reference Lightcap and Kamat147 demonstrate the novel architecture of 3D QD-sensitized graphene photoelectrodes [Fig. 11(a)], which represents a significant step toward overcoming conductivity problems inherent to QD films and opens a new avenue toward improved sensitizer loading. Furthermore, this device architecture [Fig. 11(b)], displayed improved photocurrent response (150%) over those prepared without GO attributed to high collection of photogenerated electrons through the GO network in QD–GO composite films, is expected to minimize charge recombination losses at QD grain boundaries.

FIG. 11. Schematic illustration of (a) comparing electron transport in QD films with and without graphene layer and (b) QD–graphene composite-based QDSCs; reprinted with permission from American Chemical Society. Reference Lightcap and Kamat147 (c) Three-dimensional enclosure of the GQD core by the alkyl chains; reprinted with permission from American Chemical Society. Reference Li and Yan148 (d) TEM images of green-luminescent GQDs prepared by electrochemical oxidation of a graphene electrode in phosphate buffer solution, and the inset is a photo of a GQD aqueous solution under UV irradiation (365 nm); reprinted with permission from John Wiley and Sons. Reference Li, Hu, Zhao, Shi, Deng, Hou and Qu149 (e) J–V performance of GQD-sensitized TiO2 QDSCs with two different GQD orientations (GQDs represented as circular discs). Reference Hamilton, Li, Yan and Li150 (f) Energy level diagram of the C132A molecule (GQD) on the TiO2 surfaces (VBM, valence band maximum; CBM, CB minimum); reprinted with permission from American Chemical Society. Reference Williams, Nelson, Yan, Li and Zhu151

Li and Yan Reference Li and Yan148 explored functionalized GQDs as novel sensitizers in mesoscopic solar cells through tuning the band gap from UV to visible light wave length. The expected aggregation of GQDs into graphite was overwhelmed through shielding the graphene from one another by enclosing them in all three dimensions. This is achieved by covalently attaching multiple 1,3,5-trialkyl-substituted phenyl moieties (at the 2-position) to the edges of graphene [Figs. 11(c) and 11(d)]. Reference Hamilton, Li, Yan and Li150 The shielded GQDs were demonstrated as sensitizers in triiodide-based DSSC configuration, but it showed a poor J SC of 200 μA/cm2, and a V OC of 0.48 V were produced with a fill factor of 0.58. Reference Yan, Cui, Li and Li152 The much lower current density is attributed to the low affinity of 1 with the oxide surfaces as a result of physical adsorption and the consequent poor charge injection from GQDs to TiO2. Later, the orientation of GQDs (in plane with substrate) were modified as disk-like shapes, and it improves the energy conversion performance [Fig. 11(e)] compared to “face-on” orientation due to higher sensitizer packing density that exists in this structure. Reference Hamilton, Li, Yan and Li150 Recently, Williams et al. Reference Williams, Nelson, Yan, Li and Zhu151 studied the possibility of hot electron injection at GQD-anchored single crystal TiO2 (110); this evinces that the graphene nanomaterials have feasibilities of implementing hot carrier solar cells. Nevertheless, the CB position of TiO2 is close to the HOMO level of GQDs, which allows the recombination of electrons [boomerang effect; arrow indicated in Fig. 11(f)]. Moreover, the graphene nanostructure has to be designed with a size of hundreds of nanometers to micrometers, which can be possible using graphene flakes or graphene nanoribbons. These graphene nanostructures anticipated to serve as the hot carrier chromophore allowing multiple electronic excitations under particular experimental conditions. Therefore, it is anticipated that, by the synergetic approach of hot electron harvesting and minimizing recombination at TiO2/GQD interfaces through proper interfacial engineering, GQDs are superficial sensitizers in mesoscopic solar cells. Reference Williams, Nelson, Yan, Li and Zhu151

D. Graphene-based OPVs

Recently, OPVs have attracted extensive research and development due to their potential as lightweight, flexible, conformal, and low-cost power sources for various applications. Reference Krebs153 The working principle of a simple OPV is presented in Fig. 12(a), Reference Su, Lan and Wei154 which involved many stages for photon-to-electron conversion. First, under light absorption, an electron in the donor undergoes photoinduced excitation forming a Frenkel exciton, and these excitons must diffuse to the donor–acceptor (D–A) interfaces within the diffusion length to prevent recombining to the ground state. This D–A interface concept is analogous in terms of charge transport to a P–N junction in an inorganic semiconductor. Subsequently, an exciton at a D–A interface undergoes the CT process at an ultrafast scale (∼100 fs) to form a CT exciton, where the hole and electron remain in the donor and acceptor phases, respectively, held together through columbic attraction. Finally, the CT exciton dissociates, as a result of the built-in electric field, into free holes and electrons, which are then transported through the donor and acceptor phases, respectively, to their respective electrodes. OPVs display as a large-scale transformative solar technology and are made from nontoxic and earth-abundant materials. Despite the high capability in large-scale fabrication, their performance could be improved for commercial applications. Currently OPVs exhibit PCEs of ∼8 to 9% in prototype cells. Reference He, Zhong, Su, Xu, Wu and Cao160–Reference Small, Chen, Subbiah, Amb, Tsang, Lai, Reynolds and So162 Theoretical models suggest that the efficiency could be improved to >10% for single cells and >15% for tandem cells. To achieve these performance goals, advances in the design of stable device structures are required. In addition, interface engineering also plays a crucial role in determining the performance of OPV devices. To date, graphene-based materials have been utilized as transparent electrodes, Reference Gomez De Arco, Zhang, Schlenker, Ryu, Thompson and Zhou156,Reference Lee, Tu, Yu, Li, Hwang, Lin, Chen, Chen, Chen and Chen159,Reference Park, Brown, Bulović and Kong163–Reference Eda, Fanchini and Chhowalla165 electron acceptors or hole transporters, etc. in view of elevating the performances of OPV devices. Recently, Yong et al. predicted that nanostructured graphene-based photovoltaics can yield higher than 12% (and 24% in a stacked structure) [Fig. 12(b)] and strongly recommend applying semiconducting graphene (functionalized graphene) as the photoactive material and metallic graphene (pristine) as the conductive electrodes in OPV devices.

FIG. 12. (a) Mechanism of the photon-to-electron conversion process in bulk heterojunction solar cells; reprinted with permission from Elsevier. Reference Su, Lan and Wei154 (b) Theoretical efficiency of graphene-based OPV cells proposed by Yong and Tour Reference Yong and Tour155 ; reprinted with permission from John Wiley and Sons. (c) Schematic structure of graphene TCE-based OPV shows the corresponding sample photo and transmittance spectra with a band diagram of graphene-based OPV; reprinted with permission from American Chemical Society. Reference Gomez De Arco, Zhang, Schlenker, Ryu, Thompson and Zhou156 (d) J–V characteristics of the photovoltaic devices based on aniline-functionalized GQDs with different GQD content; reprinted with permission from American Chemical Society. Reference Gupta, Chaudhary, Srivastava, Sharma, Bhardwaj and Chand157 (e) Energy level diagram of the inverted structure OPV with graphene cathode, J–V characteristics (bottom figure); reprinted with permission from American Institute of Physics. Reference Jo, Na, Oh, Lee, Kim, Wang, Choe, Park, Yoon, Kim, Kahng and Lee158 (f) Cross-sectional SEM image of OPV with graphene cathode layer; J–V characteristics of the semitransparent polymer solar cells consisting of graphene cathodes (bottom image); reprinted with permission from American Chemical Society. Reference Lee, Tu, Yu, Li, Hwang, Lin, Chen, Chen, Chen and Chen159

Plenty of research work has been demonstrated on graphene as TCEs, since [Fig. 12(c)] graphene shows high transparency (>80%) in a wide window, low sheet resistivity (R s < 100 Ω/sq), and an appropriate work function (4.5–5.2 eV). Reference Wan, Long, Huang and Chen166 One of the critical issues in OPVs compared to conventional inorganic solar cells is the charge separation rate at D–A interfaces. In the case of inorganic solar cells, the excitons are generated in the form of free electrons and holes, but in OPVs, it generates closely bound electron–hole pairs. Therefore, to separate these closely bound electron–hole pairs, an electron acceptor is essential to the built-in internal field at the interface to break up excitons that diffuse there into free carriers. For making efficient charge separation at D–A interfaces, the electron affinity of the anode layer is larger than that of the donor polymer. Currently, combination of poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT) or poly(3-octylthiophene) (P3OT) with [6,6]-phenyl-C61-butyric acid methyl ester (PCBM) has been utilized as the electron D–A pair in OPVs. However, the fullerene-based PCBM is not necessarily the optimum choice for electron acceptors in view of the relatively low PCE of the OPVs. In view of separating electrons at D–A interfaces, graphene can be considered as a promising electron acceptor Reference Lee, Tu, Yu, Li, Hwang, Lin, Chen, Chen, Chen and Chen159,Reference Abdulalmohsin and Cui167–Reference Zhong, Zhong, Mao, Wang, Wang, Qi, Loh, Wee, Chen and Chen173 owing to their high charge mobility as high as 7 × 104 cm2/V/s. In addition, due to their high specific surface area for a large interface, high mobility, and tunable band gap, GQDs Reference Gupta, Chaudhary, Srivastava, Sharma, Bhardwaj and Chand157 exhibit great potential as an electron acceptor material in photovoltaic devices [Fig. 12(d)]. In an OPV device, photoconversion efficiency of the cells governs with the cathode layer, which could satisfy the following properties: (i) to adjust the energetic barrier height between the active layer and the transparent electrodes (it determines the V OC of the cell) [Fig. 12(e)] Reference Jo, Na, Oh, Lee, Kim, Wang, Choe, Park, Yoon, Kim, Kahng and Lee158 and (ii) to form a selective transporting layer for holes while blocking the electrons. Graphene has been widely applied as a potential cathode layer Reference Jo, Na, Oh, Lee, Kim, Wang, Choe, Park, Yoon, Kim, Kahng and Lee158,Reference Kim, Mohd Yusoff and Jang174,Reference Park, Chang, Smith, Gradečak and Kong175 [Fig. 12(f)] in OPVs as is effectively managing the abovementioned properties. Recent reviews by Chen et al. Reference Chen, Zhang, Liu and Li48 and Iwan and Chuchmała Reference Iwan and Chuchmała176 contain detailed literature survey on graphene-based polymer solar cells with perspectives and challenges.

IV. SUMMARY AND PERSPECTIVES

In summary, several processes have been developed for graphene synthesis, and its utilization in different components of next generation solar cells were demonstrated. To date, graphene is applied in solid-state solar cells, DSSCs, QDSCs, and OPVs, owing to its versatile multifunctional properties such as optical, electrical, electrocatalytic, and mechanical properties. Primarily, the unprecedented mechanical property combined with excellent electrical and optical properties fosters graphene as an ideal candidate to replace conventional TCOs in next generation flexible solar cells. Exclusively, graphene offers a wide solar spectrum harvesting (visible to IR range) in a photovoltaic device, which is suitable in panchromatic or tandem solar cells. Therefore, it is anticipated that applying graphene as transparent electrodes will further improve the quantum efficiency of a solar cell, which will further result in the enhancement in cell efficiency. The recent demonstration on hot electron injection possibility from graphene to metal oxide systems encourages graphene as a promising material for highly efficient broadband extraction of light energy into multiple hot-carrier generation. However, current issues with recombination of bound electron–hole pair at graphene/metal oxide (TiO2) interface (boomerang effect) can be overwhelmed in near future by inserting shell layer coating (high Fermi level than TiO2). It is anticipated that the combination of broadband absorption and hot-carrier multiplication enables graphene to efficiently convert light energy from the full solar spectrum into electricity. In solid-state solar cells, graphene is utilized to form a Schottky junction owing to its flexibility in tuning work function. Besides the effective CT rate of the graphene-based Schottky junction, the following issues have to be addressed: (i) trade-off between conductivity and transparency of the graphene, (ii) controlling the sheet resistance and simultaneously modulating the work function of graphene, and (iii) lowering the recombination probability through the existing large quantity of the interface at the graphene–semiconductor interface. One of the effective approaches may reduce the interface states at the graphene–semiconductor interface by depositing an appropriate passivation layer on the semiconductor surface. The research has to be initiated to optimize the suitable passivation material for making a highly efficient graphene Schottky junction, which may open new avenues in nanoelectronics as well as in solid-state solar cells. On the other hand, the defect-induced or -doped graphene (promoting edge-plane sites) exhibits superior catalytic activity compared with pristine graphene and thus offer remarkable application as electrocatalytic CEs in DSSCs. In this context, applying functionalized graphene electrodes to the hybrid solar cells (like DSSCs, QDSCs, and OPVs) improve the interfacial CT kinetics at the electrode–electrolyte interfaces. Therefore, graphene and graphene-derived materials have been widely applied as DSSC photoanode and CE parts. It is appreciated that for the last few years, a significant amount of research has been invested on functionalized graphene (chemical and physical approach). Similarly, this approach can also be extended to QDSCs, since Pt shows poising effect with polysulfide electrolyte, which can be solved by graphene or graphene composite-based CEs. Though graphene extends its superior electrocatalytic property toward triiodide or polysulfide reduction in mesoscopic solar cells (DSSCs and QDSCs), controlled synthesis of graphene (impurity-free from other chemical residues) is necessary.

For future work, controlled synthesis of graphene is necessary, which needs to be free from other chemical residues to achieve extraordinary properties of graphene. In particular, controlling graphene's morphologies, using functionalizations, and optimizing the defect concentration would be more advantageous to achieve superior catalytic activities of graphene. Additionally, massive interfacial engineering is necessary to subjugate interfacial voltage drop and leakage current, which will further improve the FF, current density, and open circuit voltage of graphene-based photovoltaic devices. In this context, owing to its excellent combination of properties, there are still lots of rooms available to open up graphene-based novel device architectures (like tandem solar cells, etc.) for photovoltaic applications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the support of the WCU (World Class University) program through the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (Grant No. R31-2008-000-10092) and Engineering Research Center Program (Grant No. 2012-0000591).