Introduction

There has been an increasing demand for health care (Morgans & Burgess, Reference Morgans and Burgess2012; Segal & Bolton, Reference Segal and Bolton2009). Yet, researchers have reported that healthcare workers may be unable to meet the demands of hospitals due to long work time, night shifts, irregular work schedules, work overload, challenging interactions with doctors, other staff, patients, and their own families (Abiodun, Osibanjo, Adeniji, & Iyere-Okojie, Reference Abiodun, Osibanjo, Adeniji and Iyere-Okojie2014; AlAzzam, AbuAlRub, & Nazzal, Reference AlAzzam, AbuAlRub and Nazzal2017; Dåderman & Basinska, Reference Dåderman and Basinska2016; Ghislieri, Gatti, Molino, & Cortese, Reference Ghislieri, Gatti, Molino and Cortese2017; Mache, Bernburg, Vitzthum, Groneberg, Klapp, & Danzer, Reference Mache, Bernburg, Vitzthum, Groneberg, Klapp and Danzer2015; Munir, Nielsen, Garde, Albertsen, & Carneiro, Reference Munir, Nielsen, Garde, Albertsen and Carneiro2012; Ozutku & Altındis, Reference Ozutku and Altındis2013; Van Gordon, Shonin, Zangeneh, & Griffiths, Reference Van Gordon, Shonin, Zangeneh and Griffiths2014). Furthermore, due to responding to such high job demands, healthcare workers spend their energy and time in the work domain while they have less energy and time for the family domain (AlAzzam, AbuAlRub, & Nazzal, Reference AlAzzam, AbuAlRub and Nazzal2017; Mache et al., Reference Mache, Bernburg, Vitzthum, Groneberg, Klapp and Danzer2015). As a result, they face problems with maintaining a balance between work life and family life (Grzywacz, Frone, Brewer, & Kovner, Reference Grzywacz, Frone, Brewer and Kovner2006), which ultimately cause a work–family conflict (WFC).

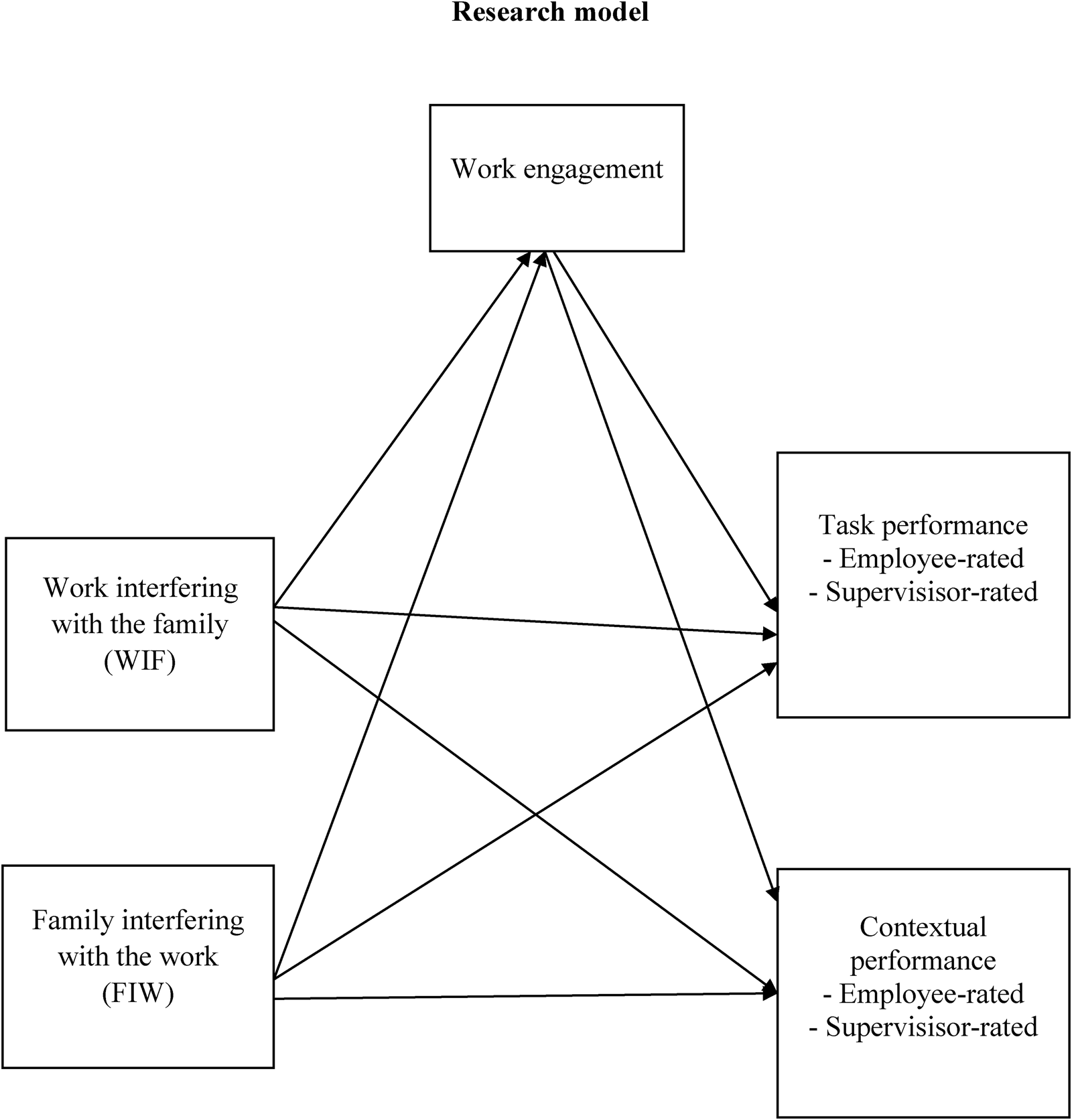

Individuals have multiple roles in both work and family lives, and they can engage in these roles (Rothbard, Reference Rothbard2001). When the demand of time and energy required in these roles is too high to be able to fulfill the role adequately, WFC emerges and harms the individual and his or her participation in these roles (Voydanoff, Reference Voydanoff2005). WFC is bi-directional: (a) work interfering with the family (WIF), and (b) family interfering with the work (FIW) (Carlson, Kacmar, & Williams, Reference Carlson, Kacmar and Williams2000; Frone, Russell, & Cooper, Reference Frone, Russell and Cooper1992; Greenhaus & Beutell, Reference Greenhaus and Beutell1985; Netemeyer, Boles, & McMurrian, Reference Netemeyer, Boles and McMurrian1996; Voydanoff, Reference Voydanoff2005) and it has possible negative effects on work outcomes, as well as work engagement and job performance (Amstad, Meier, Fasel, Elfering, & Semmer, Reference Amstad, Meier, Fasel, Elfering and Semmer2011; Li, Bagger, & Cropanzano, Reference Li, Bagger and Cropanzano2017; Opie & Henn, Reference Opie and Henn2013; Yustina & Valerina, Reference Yustina and Valerina2018). In this study, drawing on the Job Demands and Job Resources (JD-R) model (Demerouti, Bakker, De Jonge, Janssen, & Schaufeli, Reference Demerouti, Bakker, De Jonge, Janssen and Schaufeli2001a, Reference Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner and Schaufeli2001b; Opie & Henn, Reference Opie and Henn2013), we examine the effect of WFC on job performance in the mediating role of work engagement.

We expect to make contributions to the existing literature in several ways with this study. First, the current study includes both employee-rated and supervisor-rated performance evaluations, which enable us to test the effect of WFC on supervisor-rated job performance. To do so, we can provide more empirical evidence regarding the WFC and job performance literature. There is a widespread view that WFC affects job performance negatively. However, the evidence about the relationship between WFC and job performance provides mixed results (Li, Bagger, & Cropanzano, Reference Li, Bagger and Cropanzano2017). These results are differed by employee-rated and supervisor-rated job performance. For example, many researchers have reported that WFC is not related to the supervisor-rated task and contextual performance (e.g., Gilboa, Shirom, Fried, & Cooper, Reference Gilboa, Shirom, Fried and Cooper2008; Odle-Dusseau, Britt, & Greene-Shortridge, Reference Odle-Dusseau, Britt and Greene-Shortridge2012; Wang, Walumbwa, Wang, & Aryee, Reference Wang, Walumbwa, Wang and Aryee2013; Wayne, Lemmon, Hoobler, Cheung, & Wilson, Reference Wayne, Lemmon, Hoobler, Cheung and Wilson2017) while others have reported a significant relationship between WFC and supervisor-rated task and contextual performance (e.g., Netemeyer, Maxham, & Pullig, Reference Netemeyer, Maxham and Pullig2005).

Second, in this study, we examine the bi-directional form of WFC (WIF and FIW) and their effects on job performance. Therefore, we will provide empirical evidence for the existing literature by testing the cross-domain hypotheses and matching-domain hypotheses which are two important hypotheses regarding the consequences of WFC. The matching-domain hypotheses suggest that WIF should be related to work-domain outcomes and FIW should be related to family-domain outcomes (Amstad et al., Reference Amstad, Meier, Fasel, Elfering and Semmer2011). In contrast, the cross-domain hypotheses posit that WIF should be related to family-domain outcomes and FIW should be related to work-domain outcomes (Frone, Russell, & Cooper, Reference Frone, Russell and Cooper1992). Despite these hypotheses, empirical support for both hypotheses is far from being conclusive (Li, Bagger, & Cropanzano, Reference Li, Bagger and Cropanzano2017). For example, Li, Lu, and Zhang (Reference Li, Lu and Zhang2013) supported the cross-domain theory by showing that FIW was associated with job performance significantly while WIF was not. By contrast, Muse and Pichler (Reference Muse and Pichler2011) found that WIF was associated with job performance significantly rather than FIW, which supports the matching-domain theory. According to Muse and Pichler (Reference Muse and Pichler2011), there is still limited evidence that WFC is a robust predictor of job performance due to these conflicting findings. However, it is important to determine which life domain is effected by WFC. In order to persuade the managers for adopting family-friendly policies, there is needed empirical evidence about the negative effect of WFC on work-related outcomes.

Third, we examine a comprehensive research model, which enables us to analyze which form of WFC affects which form of job performance. By analyzing these effects, we aim to contribute to the extant literature. Since it is still unclear which form of WFC affects which form of job performance. According to a meta-analysis, the relationship between WIF and task performance was negative and weak (r = −.11), while the relationship between WIF and contextual performance was negative and strong (r = −.63). Similar to these results, the relationship between FIW and task performance was also negative and weak (r = −.20), and FIW with contextual performance was also negative and strong (r = −.54) (Amstad et al., Reference Amstad, Meier, Fasel, Elfering and Semmer2011). However, job performance is one of the core components for the success of organizations. Therefore, examining the factors affecting job performance is very important. One of the factors affecting job performance is WFC. Our study includes both employee-rated and supervisor-rated performance evaluations besides the bi-directional form of WFC and two dimensions of job performance (task and contextual performance).

Fourth, we aim to test the mediating role of work engagement in the relationship between WFC and job performance based on the JD-R model. By doing so, we also provide empirical evidence for WFC and job performance, as well as the JD-R model. Although some studies examined how WFC affects job performance (Frone, Yardley, & Markel, Reference Frone, Yardley and Markel1997; Greenhaus, Bedeian, & Mossholder, Reference Greenhaus, Bedeian and Mossholder1987; Kossek & Nichol, Reference Kossek and Nichol1992; Netemeyer, Maxham, & Pullig, Reference Netemeyer, Maxham and Pullig2005), our knowledge of the underlying mechanism in this relationship is still limited. Furthermore, Allen, Herst, Bruck, and Sutton (Reference Allen, Herst, Bruck and Sutton2000) recommended to the researchers for further investigation of the underlying mechanism in the relationship between WFC and job performance.

Finally, the present study examines the nurses and healthcare personnel working at different public hospitals in Turkey. In the existing WFC literature, mostly North American samples were used (Casper, Eby, Bordeaux, Lockwood, & Lambert, Reference Casper, Eby, Bordeaux, Lockwood and Lambert2007). Therefore, the other purpose of this study is to respond to calls for research in different cultures outside of the United States and Europe (Casper & Swanberg, Reference Casper and Swanberg2011; Poelmans, O'Driscoll, & Beham, Reference Poelmans, O'Driscoll, Beham and Poelmans2005), and to investigate the effect of WFC on job performance via work engagement in a sample of Turkish health professionals. In Turkey, the inadequacy of the number of health workers has long been acknowledged. According to The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) data, in 2017, the number of doctors per 100,000 people in Turkey is 186 (the number of doctors per thousand people in OECD countries, the highest 659, and the lowest 186) (Turkish Health Ministry, 2019). Likewise, the number of nurses per 100,000 people in Turkey is 272, which is the lowest number among OECD countries (the highest number is 2121) (Turkish Health Ministry, 2019). In this respect, the present study contributes to the relevant literature with its sample group.

Hypotheses setting

WFC and work engagement

WFC is a bi-directional construct, which consists of WIF and FIW. WIF refers to ‘a form of inter-role conflict in which the general demands of, time devoted to, and strain created by the job interfere with performing family-related responsibilities’, and FIW refers to ‘a form of inter-role conflict in which the general demands of, time devoted to and strain created by the family interfere with performing work-related responsibilities’ (Netemeyer, Boles, & McMurrian, Reference Netemeyer, Boles and McMurrian1996, p. 401).

Scahufeli, Salanova, Gonzalez-Roma, and Bakker (Reference Scahufeli, Salanova, Gonzalez-Roma and Bakker2002) define engagement as ‘a positive, fulfilling and satisfying work-related mental state of mind characterized by vigor, dedication and absorption’ (p. 74). Work engagement refers to a more permanent and persistent mental state that does not consist of a specific or momentary situation and does not focus on a specific purpose, event, individual, or behavior. Engaged workers often have a broader understanding of that position and are more likely to move beyond the formal limits of their job to support the company as a whole.

Halbesleben, Harvey, and Bolino (Reference Halbesleben, Harvey and Bolino2009) argued that the relationship between WIF and work engagement was explained by the conservation of resources theory (COR) developed by Hobfoll (Reference Hobfoll1989). According to Halbesleben, Harvey, and Bolino (Reference Halbesleben, Harvey and Bolino2009), engaged workers spend less energy in the family because they spend their limited energy in the workplace and this situation increase WIF. They found a positive correlation between WIF and work engagement. In addition, the JD-R model examines the relationship between work engagement and WIF. More specifically, WIF is conceptualized as a job demand in the JD-R model developed by Demerouti et al., (Reference Demerouti, Bakker, De Jonge, Janssen and Schaufeli2001a, Reference Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner and Schaufeli2001b). Drawing on this model, Opie and Henn (Reference Opie and Henn2013) showed that there was a negative relationship between WIF and work engagement. We draw on the JD-R model in the present study and develop our Hypothesis 1a as follows:

Hypothesis 1a: There is a negative relationship between WIF and work engagement.

According to Voydanoff (Reference Voydanoff2002), WFC emerges because of two reasons; overload and interference. Overload occurs when the total demand of time and energy required in multiple roles is too high to be able to fulfill the role adequately. Interference arises when conflicts in multiple roles are the result of difficulties in meeting the role expectations. This is often the case when requests in multiple roles need to be met at the same time, or anticipated contradictions in multiple roles (Voydanoff, Reference Voydanoff2002). The employee, who cannot meet the demands expected from the workplace due to the demands from the family, will experience conflict and stress (Demerouti, Shimazu, Bakker, Shimada, & Kawakami, Reference Demerouti, Shimazu, Bakker, Shimada and Kawakami2013; Idrovo Carlier, Llorente, & Grau, Reference Idrovo Carlier, Llorente and Grau2012). Studies have shown that FIW increases work stress and absenteeism (Anderson, Coffey, & Byerly, Reference Anderson, Coffey and Byerly2002) and decreases job performance (Frone, Yardley, & Markel, Reference Frone, Yardley and Markel1997; Netemeyer, Maxham, & Pullig, Reference Netemeyer, Maxham and Pullig2005). In this case, FIW will negatively affect the level of work engagement by lowering the motivation of the employee at the workplace. Kahn (Reference Kahn1990) regarded work engagement as one of the important motivational concepts (as cited in Rich, Lepine, and Crawford, Reference Rich, Lepine and Crawford2010). For this reason, we hypothesize the relationship between FIW and work engagement as follows:

Hypothesis 1b: There is a negative relationship between FIW and work engagement.

Work engagement and job performance

Job performance is divided into task performance and contextual performance (Borman & Motowidlo, Reference Borman and Motowidlo1997), which are also called intra-role job performance (task performance) and extra-role job performance (contextual performance). Task performance is the individual efficiency of the technical structure of the organization, which relates to how well the individual reflects the tasks required by the job (Goodman & Svyantek, Reference Goodman and Svyantek1999). Contextual performance is the activities that supporting the managerial, social, and the psychological work environment, such as helping their colleagues to complete a task, working collaboratively, and/or contributing to improving organizational processes (Borman & Motowidlo, Reference Borman and Motowidlo1997; Van Scotter, Reference Van Scotter2000). These activities are also called discretionary behaviors or organizational citizenship behaviors (Goodman & Svyantek, Reference Goodman and Svyantek1999).

Goodman and Svyantek (Reference Goodman and Svyantek1999) developed a contextual performance scale based on previous literature regarding organizational citizenship behavior (e.g., Smith, Organ, and Near, Reference Smith, Organ and Near1983). This scale has two subscales as altruism and conscientiousness. Altruism refers to ‘a disposition to help specific people in a direct, immediate, and often face-to-face sense’ (Goodman & Svyantek, Reference Goodman and Svyantek1999, p. 262). However, conscientiousness includes citizenship behaviors related to the organization and more impersonal behaviors rather than behaviors related to the others directly. In our study, we focus on citizenship behaviors towards individuals. Therefore, altruism defined by Goodman and Svyantek (Reference Goodman and Svyantek1999) will be used as contextual performance in this study.

Kahn (Reference Kahn1990) describes engagement as a state in which ‘people employ and express themselves physically, cognitively, and emotionally during role performances’ (p. 694). According to Rothbard (Reference Rothbard2001), engagement is ‘being psychologically present, focusing on the activities of the role,’ and ‘this is an important component of effective role performance’ (p. 656). Engaged workers are more alert and focused on their jobs. Therefore, work engagement should be positively related to task performance (Bakker, Schaufeli, Leiter, & Taris, Reference Bakker, Schaufeli, Leiter and Taris2008). For this reason, we hypothesize as follows:

Hypothesis 2a: Work engagement is positively related to task performance.

If people invest energy in their job roles, they should show higher prosocial behaviors, which is linked to the tendency of a person to act in ways that promote an organization's social and psychological context (Borman & Motowidlo, Reference Borman, Motowidlo, Schmitt and Borman1993). We therefore expect to see a positive link between work engagement and contextual performance.

Hypothesis 2b: Work engagement is positively related to contextual performance.

The mediating role of work engagement

In general, WIF has been considered to be related to home-domain outcomes by researchers who adopt cross-domain hypotheses (e.g., Green, Bull Schaefer, MacDermid, & Weiss, Reference Green, Bull Schaefer, MacDermid and Weiss2011). In addition, some researchers have begun to direct their attention to the question of how WIF affects workplace outcomes. Amstad et al. (Reference Amstad, Meier, Fasel, Elfering and Semmer2011) have suggested that WIF may affect work outcomes negatively. However, there is still a lack of empirical evidence that demonstrates the relationship between WIF and workplace outcomes (Wayne et al., Reference Wayne, Lemmon, Hoobler, Cheung and Wilson2017).

A number of studies have also examined the job performance as an outcome of FIW, based on cross-domain effect (e.g., Li, Lu, & Zhang, Reference Li, Lu and Zhang2013) and COR theory (e.g., Mercado & Dilchert, Reference Mercado and Dilchert2017). What these studies have in common is the idea that when FIW is high, it would impede further engagement in the workplace and workers do not have enough physical and cognitive capacity to spend more energy in their work, contributing to an insufficient job performance level. Workers are less likely to have the necessary resources for the task performance or to work beyond that which is required to cover extended work hours because of the pressures of their family roles. Thus, FIW is expected to be negatively related to job performance.

In the present study, we draw on the JD-R model (Demerouti et al., Reference Demerouti, Bakker, De Jonge, Janssen and Schaufeli2001a, Reference Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner and Schaufeli2001b; Opie & Henn, Reference Opie and Henn2013) to explain the relationship between WFC (WIF and FIW) and job performance (task and contextual performance). According to this model, job demands are the physical and psychological efforts, necessary to sustain a job physically, psychologically, socially, and organizationally, which are also related to physical and/or psychological costs. Job demands (such as an overload) cause the employee to load too many tasks and to deplete in the long run. Based on the JD-R model, work engagement mediates the relationship between job resources, job demands, and job outcomes.

When healthcare employees cannot cope with family and work roles due to increased family and work responsibilities, they will experience WFC which leads to stress (Jenkins, Heneghan, Bailey, & Barber, Reference Jenkins, Heneghan, Bailey and Barber2016). Furthermore, healthcare employees experiencing stress cannot focus on their work roles because of reaction to stress (Davis, Gere, & Sliwinski, Reference Davis, Gere and Sliwinski2017). Subsequently, they will withdraw from their job. As a result, their work engagement and job performance will decrease. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3a. Work engagement will mediate the relationship between WIF and task performance.

Hypothesis 3b. Work engagement will mediate the relationship between WIF and contextual performance.

Hypothesis 4a. Work engagement will mediate the relationship between FIW and task performance.

Hypothesis 4b. Work engagement will mediate the relationship between FIW and contextual performance.

We have shown our research model in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Research model.

Method

Sample

The sample of the study consisted of 432 health personnel and 61 supervisors working in six different public hospitals in Turkey. 78% of healthcare personnel were females. 54% were married and 35.2% had children. 59.5% were holding an undergraduate degree and 5.1% were holding graduate degrees. 35.2% of these participants worked only during daily working hours, 64.8% worked night and day shifts and 72.2% worked overtime on weekends. The age of the health personnel varied between 18 and 60 years and the median age is 31, sd = 7.61. The average tenure of total experience was 9.46, sd = 7.96, the average organizational tenure was 6.25, sd = 6.6, and the average departmental tenure was 4.37, sd = 5.2. Of the 61 supervisors, almost all of them (93.4%) consisted of females. 73.8% of the supervisor were married and 71.2% had children. 16.4% of them held a master's degree, 49.2% an undergraduate degree, and 34.4% a graduate degree. 95.1% of supervisors worked only during daily working hours and 16.4% worked overtime on weekends. The average age of the supervisors varied between 24 and 60 years and the average age was 38.75, sd = 7.31. The average tenure of total experience was 17.11, sd = 7.76, the average organizational tenure was 13.44, sd = 8.4 and the average departmental tenure was 8.52, sd = 8.04. When we examine the characteristics of the supervisors in general, we see that the level of their education, age, and professional experience was higher than their subordinates.

Procedure

We developed two questionnaire forms (for employees and supervisors) as data collection tools. The purpose of the two questionnaire forms was to evaluate employee performance, the dependent variable of the research, by both the employee and the supervisor.

The first questionnaire was for employees. This questionnaire contained all the scales and descriptive information about participants. The second questionnaire was for supervisors. Supervisors evaluated the performance of their subordinates with this questionnaire which included only task and contextual performance scales. We changed the items on the scales so that supervisors would evaluate their subordinates. The item ‘I willingly attend functions not required by the organization, but helps in its overall image,’ in the questionnaire form of the employees was changed to ‘She/he willingly attends functions not required by the organization, but helps in its overall image,’ in the questionnaire form of the supervisors.

The questionnaire forms were distributed and collected by researchers. Later, supervisors and healthcare employees were informed through face-to-face interviews about the questionnaire and they were explained in detail how to fill out the questionnaires. To ensure the confidentiality of the data, both supervisors and employees were delivered a sealed envelope, and the participants submitted the questionnaire to the researchers in a closed envelope. To combine the data of supervisors and the employees, we wrote the names of the employees who agreed to participate voluntarily in the research from each service and the questionnaire numbers on a small consent note and gave the notepaper to the supervisor. The supervisor wrote the questionnaire number of the relevant subordinate on the questionnaire which she/he would evaluate and then destroyed the notepaper in question. Questionnaires were distributed to a total of 598 healthcare employees and 61 supervisors. 502 questionnaires were filled out by employees and supervisors. The response rate was 72%. 432 out of 502 questionnaires were included in the study which was answered completely. We conducted the data collection process from May 9 to July 25, 2016.

Measures

Work engagement

We used the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9) developed by Schaufeli, Bakker, and Salanova (Reference Schaufeli, Bakker and Salanova2006) to measure employees' level of work engagement. Although this scale consists of three subdimensions, which are namely vigor, dedication, and absorption, it can be used as unidimensional. Schaufeli, Bakker, and Salanova (Reference Schaufeli, Bakker and Salanova2006), in their research with 14.521 participants in 10 countries, report that UWES-9 can also be used as unidimensional. In addition, Hallberg and Schaufeli (Reference Hallberg and Schaufeli2006, p. 125) state that there are high correlations among subdimensions of the UWES which indicate a unidimensional structure. Therefore, we used this scale as unidimensional. It is a 6-point Likert-type scale. Schaufeli, Bakker, and Salanova (Reference Schaufeli, Bakker and Salanova2006) indicated that the unidimensional scale had internal consistency with Cronbach's α > .80 in the sample consisting of 10 countries. In our study, Cronbach's α coefficient is .76.

Work–family conflict

We used a scale developed by Netemeyer, Boles, and McMurrian (Reference Netemeyer, Boles and McMurrian1996) to measure the WFC. This scale has two subdimensions, namely WIF and FIW. WIF consists of five items. ‘The demands of my work interfere with my home and family life’ is one of the sample items in this subdimension. FIW also consists of five items. One sample item is ‘The demands of my family or spouse/partner interfere with work-related activities.’ WFC scale is a 6-point Likert-type scale (1 = never and 6 = always). All the items are negative and the high scores indicate high conflict. Netemeyer, Boles, and McMurrian (Reference Netemeyer, Boles and McMurrian1996) reported the Cronbach's α coefficient for both subdimensions was above .80 in three different samples. In our study, Cronbach's α coefficient for WIF is .92, whereas for FIW is .91.

Task performance

We used a unidimensional 6-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree) with nine items developed by Goodman and Svyantek (Reference Goodman and Svyantek1999) to measure participants' task performance. Task performance was rated by the participants (employee-rated) and their supervisors (supervisor-rated). ‘I demonstrate expertise in all job-related tasks’ is a sample item for the employee-rated task performance while ‘He/She demonstrates expertise in all job-related tasks’ is a sample item for the supervisor-rated task performance. Low scores on the scale indicate low performance and high scores indicate high performance. Cronbach's α coefficient was .93 in the study of Goodman and Svyantek (Reference Goodman and Svyantek1999). In our study, Cronbach's α coefficients are .91 and .95 for employee-rated and supervisor-rated task performance, respectively.

Contextual performance

We used only the altruism subscale from the scale developed by Goodman and Svyantek (Reference Goodman and Svyantek1999). According to Goodman and Svyantek (Reference Goodman and Svyantek1999), ‘altruism’ subscale represents the organizational citizenship behavior toward individuals. In addition, there are also studies in the present literature using scales of organizational citizenship behavior toward individuals to measure contextual performance (e.g., Demerouti, Bakker, & Gevers, Reference Demerouti, Bakker and Gevers2015; Demerouti, Xanthopoulou, Tsaousis, & Bakker, Reference Demerouti, Xanthopoulou, Tsaousis and Bakker2014). Therefore, we used only the altruism subscale in our study. The altruism subscale consists of seven items. One of the items on the scale is ‘Helps others when their work load increases (assists others until they get over the hurdles).’ As it is in the task performance scale, we adopted items for using employee-rated and supervisor-rated contextual performance. This scale is also a 6-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree). The Cronbach's α coefficient was .86 in Goodman and Svyantek (Reference Goodman and Svyantek1999) study. We found Cronbach's α coefficients as .80 (for employee-rated) and .88 (for supervisor-rated) in the current study.

Controls

Age, gender, marital status, organizational tenure, and overtime work were included as control variables. There are many studies indicating the significant effect of these variables on work engagement and job performance (e.g., Frone, Russell, & Cooper, Reference Frone, Russell and Cooper1992; Halbesleben & Wheeler, Reference Halbesleben and Wheeler2008; Li, Sanders, & Frenkel, Reference Li, Sanders and Frenkel2012).

Analysis

We used SPSS 22 and AMOS 22 programs in the analysis of the research data. The AMOS (analysis of moment structures) program is a structural equation model (sem) program (Arbuckle, Reference Arbuckle1997). We followed Preacher and Hayes (Reference Preacher and Hayes2004, Reference Preacher and Hayes2008) bootstrap approach. In bootstrap analysis, bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrap confidence intervals (BCA CI) are reported (Preacher & Hayes, Reference Preacher and Hayes2008). Preacher and Hayes (Reference Preacher and Hayes2004, Reference Preacher and Hayes2008) propose bootstrap analysis which provides more valid and reliable results in mediation models. Furthermore, it is recommended to test the indirect effect with the bootstrap technique, which produces stronger and more valid results than the Sobel test. In the bootstrap analysis, the total effect (the effect of X on Y) should not be a precondition for the indirect effect. The significance of the indirect effect is determined by examining the 95% confidence interval (CI) obtained by bootstrap analysis. A total of 5,000 sample size was used to perform bootstrap analysis.

In our study, we used goodness-of-fit index (GFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) and comparative fit index (CFI) to represent model fit (Kline, Reference Kline2015). Hair, Black, Babin, and Anderson (Reference Hair, Black, Babin and Anderson2010) suggest that as a rule of thumb, at least one absolute fit index and one incremental fit index should be reported with the Chi-square (χ2) value. Values for RMSEA below .08 and for other indices above .90 were considered to indicate a good fit (Kline, Reference Kline2015).

Results

We first ran preliminary confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) to test the validity of measures. First, we conducted CFAs to examine the distinctiveness of the measures obtained from employees, including WIF, FIW, work engagement, contextual performance, and task performance. We compared the hypothesized five-factor model with other alternative models. The results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Comparison of alternative factor models (N = 432)

**p < .01; χ2 = Chi-square; df = degree of freedom; GFI = goodness-of-fit index; TLI = Tucker–Lewis index; CFI = comparative fit index; and RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation.

M1: Single-factor model (the items of all variables loaded on a single factor).

M3: Three-factor model (the items of WIF and FIW loaded on a factor, task and contextual performance loaded another second factor, and work engagement loaded another third factor).

M4: Four-factor model (the items of task and contextual performance loaded on a factor, WIF, FIW, and work engagement loaded onto their factor).

M5: Five-factor model (as five distinct factors, for which we loaded each item onto its respective higher-order factor).

Results indicated that the hypothesized five-factor measurement model had a better fit with the data than the other alternative models. These results provided support for the five-factor measurement model of WIF, FIW, work engagement, employee-rated contextual performance, and employee-rated task performance as distinct constructs in the present study. We also conducted CFAs to examine the distinctiveness of supervisor-rated task performance and supervisor-rated contextual performance. The hypothesized two-factor measurement model had a better fit with the data (χ2 = 274.630, df = 64, p = .0001, GFI = .904, TLI = .955, CFI = .96, RMSEA = .087) than the one-factor alternative model (χ2 = 433.427, df = 63, p = .0001, GFI = .85, TLI = .92, CFI = .93, RMSEA = .117; Δχ2 = 158.97, Δdf = 1, р < .0001). These results provided support for the two-factor measurement model of supervisor-rated task performance and supervisor-rated contextual performance as distinct constructs.

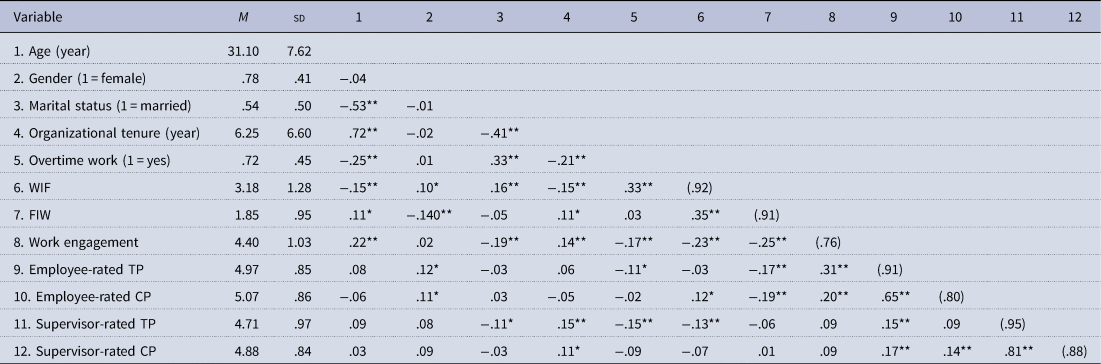

In Table 2, we present the means, standard deviations, Cronbach's α coefficients, and correlations among the study variables. Cronbach's α coefficients were above .70 which demonstrates the internal consistency of study variables. There was a negative relationship (r = −.23; p < .01) between WIF and work engagement. Similarly, there was a significant and negative relationship (r = −.25; p < .01) between FIW and work engagement. Hypotheses 1a and 1b were supported. Moreover, there was also a significant and positive relationship between work engagement and employee-rated task performance (r = .31; p < .01), employee-rated contextual performance (r = .20; p < .01). However, there was not a significant relationship between work engagement and supervisor-rated task performance and supervisor-rated contextual performance (p > .05). Hypotheses 2a and 2b were supported for employee-rated job performance while these two hypotheses were not supported for supervisor-rated job performance.

Table 2. Means, standard deviations, reliabilities, and correlations between study variables (N = 432)

WIF = work interfering with the family; FIW = family interfering with the work; TP = task performance; CP = contextual performance; M, mean; sd = standard deviation.

* p < .05, ** p < .01. Cronbach's αs are along the diagonal in the parenthesis.

Next, we tested the mediating role of work engagement in the effect of WFC on task and contextual performance. We analyzed the employee-rated task and contextual performance and the supervisor-rated task and contextual performance separately. We tested Model 1 based on employee-rated job performance to examine the mediating role of work engagement in the effect of WIF and FIW on task and contextual performance. Similarly, we also tested Model 2 based on supervisor-rated job performance to examine the mediating role of work engagement.

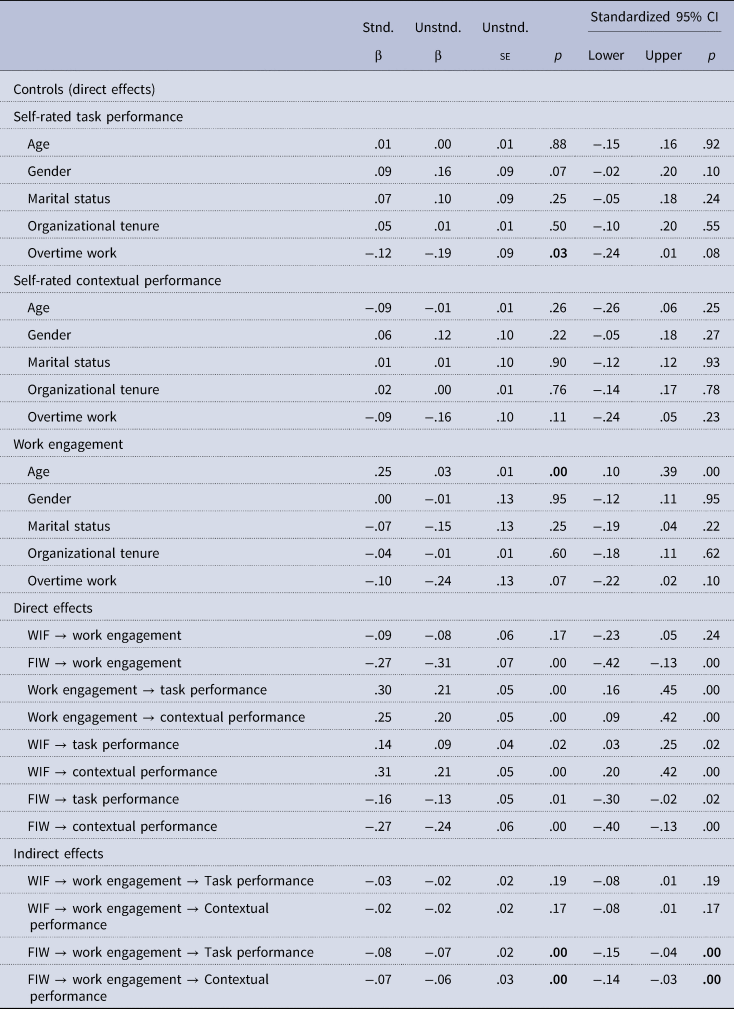

Results of testing Model 1 are presented in Table 3. Fit indices indicated that Model 1 showed a good fit with data (χ2 = 598.280, df = 307, p = .0001, GFI = .912, TLI = .947, CFI = .957, RMSEA = .047).

Table 3. Results of mediation analysis predicting employee-rated job performance

Note: β, beta; se = standard error; p = significance; CI = confidence interval; WIF = work interfering with the family; FIW = family interfering with the work.

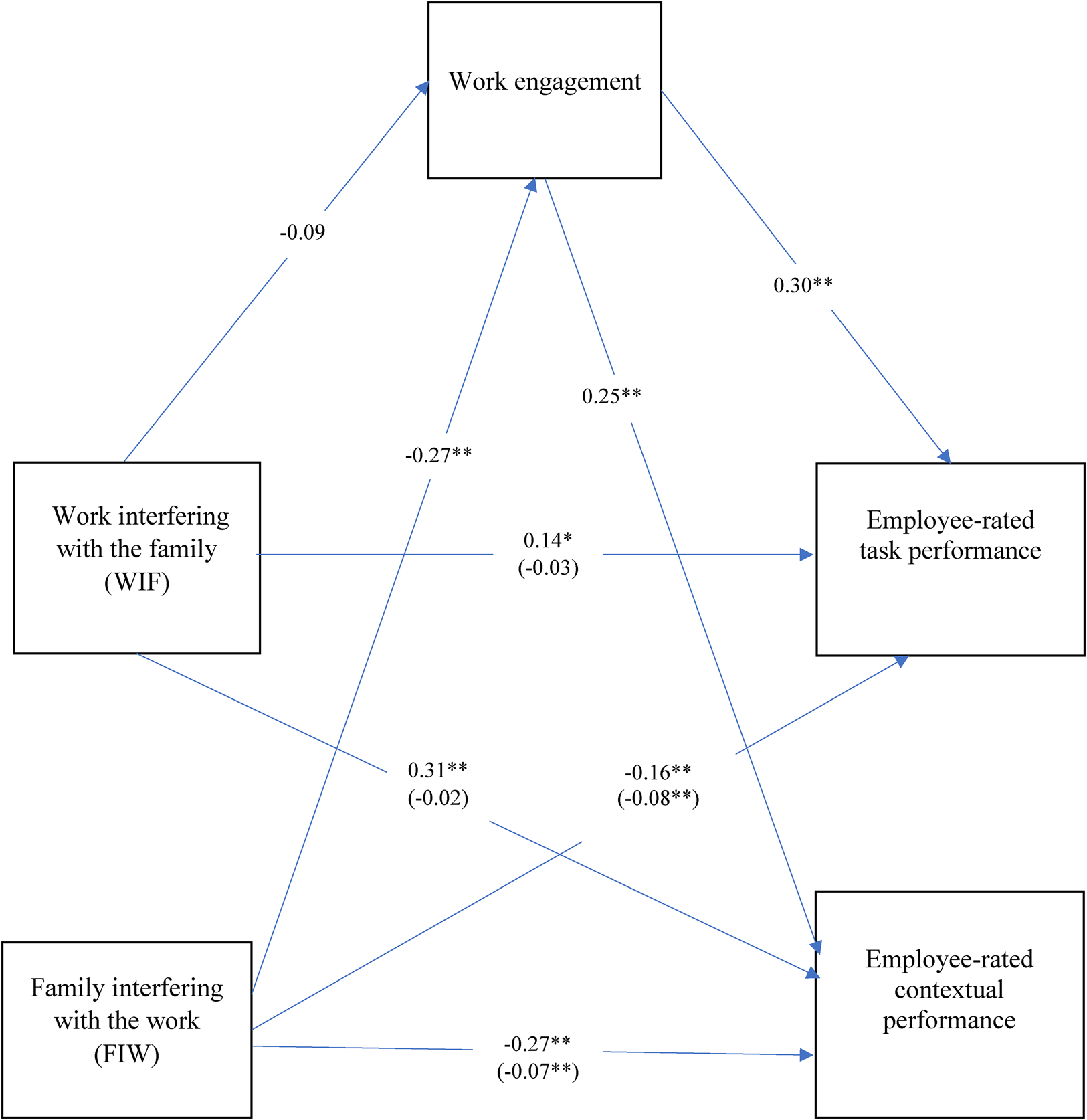

The indirect effect of work engagement in the relationship between WIF and employee-rated job performance (task and contextual performance) was not significant (p > .05). So, Hypotheses 3a and 3b were not supported for employee-rated job performance. However, the indirect effect of work engagement in the relationship between FIW and employee-rated task performance was significant (−.08, 95% CI = [−.15 and −.04]), supporting Hypothesis 4a for employee-rated job performance. We also found that the indirect effect of work engagement in the relationship between FIW and employee-rated contextual performance was significant (−.07, 95% CI = [−.14 and −.03]), supporting Hypothesis 4b for employee-rated job performance. Figure 2 indicates the results of hypotheses tests about employee-rated job performance.

Figure 2. Results of hypotheses tests.

Note: Standardized β coefficients were reported. * p < .05, ** p < .01. Indirect effects are presented with parentheses.

As a result of testing Model 2 based on supervisor-rated job performance, fit indices also demonstrated that the Model 2 fit with data well (χ2 = 771,331, df = 393, p = .0001, GFI = .896, TLI = .954, CFI = .961, RMSEA = .047). According to Table 4, the indirect effects of work engagement between WFC (WIF and FIW) and job performance (supervisor-rated task and contextual performance) were not significant (p > .05). Therefore, Hypotheses H3a, H3b, H4a, and H4b were not supported for supervisor-rated job performance.

Table 4. Results of mediation analysis predicting supervisor-rated job performance

Note: β=beta; se=standard error; p=significance; CI=confidence interval; WIF=work interfering with the family; FIW=family interfering with the work; SR=supervisor-rated.

Discussion

Scholars have begun to explore the underlying mechanism of the relationship between WFC and job performance to find out the reason for the weak relationship and conflicting results. We also hypothesized that work engagement mediated the relationship between WFC (WIF and FIW) and job performance drawing on the JD-R model. As a result of the hypotheses test, the indirect effect of FIW on the employee-rated job performance (task and contextual performance) via work engagement was significant while the indirect effect of WIF was not. However, neither FIW nor WIF had a significant direct and indirect effect on supervisor-rated job performance (task and contextual performance).

Our results suggest that healthcare employees experiencing FIW may have less physical, cognitive, and emotional resources to engage in their jobs. Hence, their work engagement may be influenced negatively by their high FIW. In the JD-R model, FIW is conceptualized as a job demand. Job demands are significantly associated with work engagement (Crawford, LePine, & Rich, Reference Crawford, LePine and Rich2010). The employees, who cannot meet the job demands because of family responsibilities, will experience conflict and stress (Demerouti et al., Reference Demerouti, Shimazu, Bakker, Shimada and Kawakami2013; Voydanoff, Reference Voydanoff2002). Employees who experience conflict and stress will not be fully motivated at work physically, cognitively, and emotionally (Kahn, Reference Kahn1990; Rothbard, Reference Rothbard2001; Scahufeli et al., Reference Scahufeli, Salanova, Gonzalez-Roma and Bakker2002). Therefore, individuals who exhibit high levels of FIW reduce their task and contextual performance because they no longer possess the necessary resources for engaging in the task and contextual performance. Witt and Carlson (Reference Witt and Carlson2006) and Li, Lu, and Zhang (Reference Li, Lu and Zhang2013) also indicated that employees who reported high FIW had lower task performance. Beham (Reference Beham2011) and Mercado and Dilchert (Reference Mercado and Dilchert2017) studies showed that FIW was negatively related to contextual performance.

In parallel to our results about FIW, there was a negative correlation between WIF and work engagement. Furthermore, as hypothesized, WIF was negatively related to supervisor-rated task performance consistent with the JD-R model. In the JD-R model (Demerouti et al., Reference Demerouti, Bakker, De Jonge, Janssen and Schaufeli2001a, Reference Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner and Schaufeli2001b; Opie & Henn, Reference Opie and Henn2013), WIF is conceptualized as a job demand and negatively related to work engagement and job performance. Our results were consistent with previous research (e.g., Mauno, Kinnunen, & Ruokolainen, Reference Mauno, Kinnunen and Ruokolainen2007; Opie & Henn, Reference Opie and Henn2013). However, the result about WIF and employee-rated contextual performance was the opposite of our expectation. WIF was positively related to contextual performance. Therefore, our findings on WIF and contextual performance do not support the JD-R model. In the literature, there are conflicting findings of the relationship between WIF and contextual performance. For example, according to Klein (Reference Klein2007) and Bolino and Turnley (Reference Bolino and Turnley2005), employees engaging in citizenship behaviors would spend more time at work. As a result, they would have less time and energy for their family, which would in turn cause WIF. They also found a positive relationship between WIF and contextual performance. In contrast, Amstad et al., (Reference Amstad, Meier, Fasel, Elfering and Semmer2011) reported that WIF was negatively related to contextual performance in their meta-analysis.

Consistent with previous studies, work engagement predicted employee-rated task and contextual performance significantly (Christian, Garza, & Slaughter, Reference Christian, Garza and Slaughter2011; Çankır & Semiz, Reference Çankır and Semiz2018; Çankır & Şahin, Reference Çankır and Şahin2018). However, work engagement did not predict supervisor-rated task and contextual performance. Bakker, Demerouti, and Verbeke (Reference Bakker, Demerouti and Verbeke2004) showed that employees who were engaged to work received higher performance scores from their managers. Chen, Shih, and Chi (Reference Chen, Shih and Chi2018) found a significant relationship between employee work engagement (Time 1 and Time 2) and supervisor-rated service performance (Time 3). Christian, Garza, and Slaughter (Reference Christian, Garza and Slaughter2011) also reported in their meta-analysis that work engagement was correlated with other-rated task performance (r = .39) and contextual performance (r = .43) significantly. Our results were inconsistent with previous research. Because of mixed findings of the effects of work engagement on other-rated job performance, researchers should investigate the underlying mechanism in this relationship.

In the Turkish healthcare context, WIF was experienced more frequently than FIW, consistent with previous studies (e.g., Frone, Russell, & Cooper, Reference Frone, Russell and Cooper1992; Kinnunen, Geurts, & Mauno, Reference Kinnunen, Geurts and Mauno2004). In our study, female respondents reported higher WIF than male respondents. However, they reported lower FIW than male respondents. Similar to female respondents, married respondents also reported higher WIF and lower FIW than single respondents. In this respect, female and married respondents suffer from WIF more than FIW, meaning that they cannot meet their family expectations because of job demands. In Wang, Tsai, Lee, and Ko (Reference Wang, Tsai, Lee and Ko2019) study, females reported lower FIW than males while there was no difference in WIF according to gender in the Taiwan sample with frontline employees. However, there are inconsistent results for African and European samples. Ghislieri et al. (Reference Ghislieri, Gatti, Molino and Cortese2017) reported that there was no difference in WIF according to gender in the Italian nursing sample. In the Jordanian nursing sample, WIF is higher for females and FIW did not differ according to gender (AlAzzam, AbuAlRub, & Nazzal, Reference AlAzzam, AbuAlRub and Nazzal2017). In Turkey, according to Hofstede's cultural dimensions, the power distance is 66%; individualism is 37%; avoidance of uncertainty is 85% and the influence of eastern culture is greater (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2019). In Asian societies, working women experience more WIF than men because of their social perspective on motherhood (Aryee, Reference Aryee1992). Our results also support this social perspective.

Theoretical implications

The Job Demands and Job Resources (JD-R) model is widely used to examine the factors affecting employee well-being and job outcomes by the researchers (Lesener, Gusy, & Wolter, Reference Lesener, Gusy and Wolter2019). The current study also aims to reveal the negative effects of WFC on healthcare employees' job performance via work engagement, drawn on the JD-R model. Job demands are found to be related to burnout in previous studies (e.g., Bakker, Demerouti, and Verbeke, Reference Bakker, Demerouti and Verbeke2004). However, burnout is not the opposite pole of work engagement. Russell and Carroll (Reference Russell and Carroll1999) have convincingly demonstrated that positive and negative affects are independent states rather than opposite poles of a bi-polar dimension (cited in Schaufeli & Bakker, Reference Schaufeli and Bakker2004, p. 294). Schaufeli and Bakker (Reference Schaufeli and Bakker2004) likewise argued that work engagement and burnout are not the opposite poles of a bipolar dimension, they are only negatively correlated mental states, independent of each other. In our study, WIF and FIW are correlated negatively with work engagement, which supports the assumption about the negative effects of job demands on work engagement. Although work engagement is strongly related to job resources (Lesener, Gusy, & Wolter, Reference Lesener, Gusy and Wolter2019), our results show that it is also related to job demands.

The present study also revealed several general findings concerning the relationship between WFC and employee-rated contextual and task performance, supervisor-rated contextual and task performance. Initially, we aim to examine the relationship between WFC and job performance, and we have defined the three debates about WFC and job performance in the present study by investigating previous studies.

First, in the previous literature, results of the relationship between WFC and job performance are differed by employee-rated and supervisor-rated job performance. In our study, FIW was not related to the supervisor-rated task and contextual performance while it was related to the employee-rated task and contextual performance. Besides, WIF was not related to employee-rated task performance and supervisor contextual performance while it was related to employee-rated contextual performance positively and supervisor-rated task performance negatively. Prior studies have also found that WFC is not related to the supervisor-rated task and contextual performance (e.g., Gilboa et al., Reference Gilboa, Shirom, Fried and Cooper2008; Odle-Dusseau, Britt, & Greene-Shortridge, Reference Odle-Dusseau, Britt and Greene-Shortridge2012; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Walumbwa, Wang and Aryee2013; Wayne et al., Reference Wayne, Lemmon, Hoobler, Cheung and Wilson2017). However, Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Walumbwa, Wang and Aryee2013) indicated that the empirical research should demonstrate the effect of employee WFC on organizational outcomes such as supervisor-rated performance, in order to persuade managers of the importance of work–family balance and to convince them to invest in achieving employees' work–life balance.

Second, there are conflicting results about two important hypotheses regarding the consequences of WFC, matching-domain hypotheses and cross-domain hypotheses. In the present study, results about FIW and employee-rated job performance may support cross-domain hypotheses. However, the findings of WIF do not support cross-domain hypotheses.

Third, it is still not clear which form of WFC affects which form of job performance. According to Amstad et al.'s (Reference Amstad, Meier, Fasel, Elfering and Semmer2011) meta-analysis, WIF and FIW were related to task performance negatively and weakly while they are associated with contextual performance negatively and strongly. In the present study, the relationship between FIW and task performance was negative and weak, similar to the relationship between FIW and contextual performance for employee-rated job performance. In addition, the relationship between WIF and task performance was negative and weak (r = −0,13 for supervisor-rated task performance), whereas the relationship between WIF and contextual performance is positive and weak (r = .12 for employee-rated contextual performance). These results are inconsistent with Amstad et al.'s (Reference Amstad, Meier, Fasel, Elfering and Semmer2011) meta-analysis. In sum, WFC was related to the task and contextual performance. However, the relationship between WFC and job performance (task and contextual performance) differed according to WFC's subdimensions, WIF and FIW.

Practical implications

In the Turkish healthcare context, employees who experience family interfering with the work have lower work engagement which leads to a decrease in their job performance. From this point of view, it is recommended that managers should develop organizational policies (flexible working hours, nursery for childcare, etc.) to help ensure the work–life balance of employees and support them in maintaining their work–life balance. Ensuring the work–life balance of healthcare employees may affect their job performance through their work engagement. Therefore, organizational performance will also increase through high job performance of the employees.

Limitations

This study has also some limitations. Initially, the research data are based on the perception of the participants. It is argued that in the employee-reporting method, the responses of the participants do not fully reflect the actual situation due to the problem of social desirability (Moorman & Podsakoff, Reference Moorman and Podsakoff1992). In order to reduce the effect of this limitation, participants delivered questionnaire forms in a closed envelope. The other limitation of data collection procedure is that supervisors evaluated more than one employee's job performance, which might have caused systematic variance. In addition, this study was designed as a cross-sectional study. In this case, the measurement error that results in autocorrelation, known as the common variance error, may occur (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). However, alternative models were tested to determine the common variance error (discriminant validity) and it was found that there was no autocorrelation between the variables affecting the findings.

Acknowledgment

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Conflict of interest

The authors state that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical Standards

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Ethical Committee of Marmara University (no.: 2016-2/7). Authorizations were obtained from Istanbul Health Directorate to collect data from hospitals (no.: 05/05/2016-24093).