Introduction

In the mainstream academic literature and media, the Islamic faith is often presented as a monolithic religion, ignoring the internal diversity or heterogeneity based on denomination, ethnicity, gender and religious practice. The monolithic understanding of Islam may be attributed to a possible lack of sophistication on the part of non-Muslim analysts as well as the general insistence of Muslim scholars that Muslims worldwide belong to one collective community, that is, the Muslim ummah. However, although there are two broad sects within Islam, that is, Sunni and Shia, the diversity within Islam is much more nuanced and heterogeneous and can be traced to different interpretations of the texts, opinions of narrators, jurisprudence and different milieus where such interpretations are enacted. For example, interpretation, geographical location and culture intersect in how gender practices such as the veil/hijab are linked to gender segregation, and injunctions on inheritance, commerce, leadership and treatment of religious and ethnic minorities, and how they are proclaimed, legislated and endorsed (e.g., Moghadam, Reference Moghadam1994; Warde, Reference Warde2000; Aitchison, Hopkins, & Kwan, Reference Aitchison, Hopkins and Kwan2007; Hamid, Reference Hamid2016). The need for research on different understandings of Islam has been recognized for some time and a few scholars have pointed out the multiplicity of Islamic perspectives rather than ‘the Islamic perspective’ (Jackson, Reference Jackson2000; Alak, Reference Alak2015). In addition, scholars signal the need to situate research on management and organizations within contextual perspectives and multiple levels of analysis (Härtel & O’Connor, Reference Härtel and O’Connor2014).

In our guest editorial, we draw on literatures from religion, gender, diversity and terrorism, to delineate different versions of Islam and Muslims and consider implication of such diversity for organizations and societies across the globe. We conclude by outlining an agenda for future research.

Heterogeneity within islam

In this section, we draw attention to the internal diversity of Islam, often overlooked or misunderstood in academic literature and the media.Footnote 1 Nasr (Reference Nasr2007) explains the different versions of Islam by introducing the divide between the Sunni and Shia sects of Islam as parallel to the divide between Catholic and Protestant sects in Christianity, with each claiming historic and theological orthodoxy. The origins of these two sects may be attributed to a schism that emerged after the Prophet Muhammad’s death in AD 632. Shias believe that the Prophet had nominated Ali, his cousin and son-in-law as caliph after him. The Sunnis believe that the Prophet did not make any explicit nomination, therefore the new leader had to be chosen by consensus. Sunnis revere four rashidun or ‘rightly guided’ caliphs after the Prophet, including Ali as the fourth caliph, whereas Shias revere 12 Imams including Ali as the first Imam (spiritual leader) (Harney, Reference Harney2016).

Both sects agree on many fundamental aspects of Islam, such as the oneness of God (tauhid), the Quran, the finality of the Prophet, five daily prayers, Hajj pilgrimage and yearly almsgiving (zakat) (BBC, 2009). There are, however, differences of jurisprudence on some of these matters, for example, to keep arms folded or unfolded during daily prayers. Such differences are also found within various subbranches of each of these sects.

The Shias are also distinct due to their participation in annual rituals of Ashura during the month of Muharram to commemorate the martyrdom of Imam Husayn, the Prophet’s grandson, by Caliph Yazid ibn Muawiya’s army in Karbala in AD 680 (Harney, Reference Harney2016). Although Sunnis too revere and mourn Imam Husayn and visit his shrine in Iraq, they do not usually participate in the Shia rituals of self-flagellation.

To add nuance to the simplistic Sunni–Shia binary, Nasr states that the two largest sects are not monolithic communities and the followers of both sects are further divided into subsects based on doctrine and/or jurisprudence (such as Hanafi, Maliki, Shafii, Jafari, Ismaili and Zaidi schools of jurisprudence) and diversity of geography, language, ethnicity and class. On the basis of this premise of diversity within Islamic sects, Nasr (Reference Nasr2007) argues that while to the Western eye, Muslim politics is defined by Islamic values, the Islamic discourse remains open to interpretation and a variety of practices. He argues that politics looks for truth in religious text but from within a perspective or context that is not purely based on religion. Individuals tend to construe, understand and read from their religious texts in line with the hopes and fears that underlie their everyday lives. Hence, it is rather unreasonable to deliberate and discuss a single Islamic reality, and even less so of one Sunni or one Shia reality.

The monolithic perspective often projected in mainstream media and academic scholarship is problematic because Muslim beliefs, interpretations and practices vary tremendously based on denomination, sect, cultural and ethnic practices, gender and religiosity. In the field of management and organization studies, this may mean that employers, managers, employees, practitioners and scholars may display naiveté in understanding the nuances within Muslim employees’ belief systems and practices. A unidimensional understanding may result in organizational theories and practices based on stereotypes, sweeping generalizations and assumptions, which may be misleading and inaccurate, and misrepresent Muslims.

For example, organizations may not understand that since 9/11, individuals and groups belonging to the ultraorthodox Salafi (or ‘Wahhabi’) and Deobandi subsects or variants of Sunni Islam are responsible for almost all incidents of suicide bombings and terrorism in the West and other parts of the world in the name of Islam (Moghadam, Reference Moghadam2009; Syed, Pio, Kamran & Zaidi, Reference Syed, Pio, Kamran and Zaidi2016). In addition, almost all violent Islamist organizations such as Al-Qaeda, ISIS, Taliban, Al-Shabab and Boko Haram responsible for mass murders and indiscriminate terrorism have ideological beliefs or affiliations associated with Salafism, Wahhabism or Deobandism. Victims of these ultraorthodox ideologies include mainstream Sunni and Shia Muslims as well as non-Muslims across the world.

Deobandi is a puritanical subsect within Sunni (primarily Hanafi) Islam, centered in South Asia. It represents a minority of Sunni Muslims in that region. However, Deobandism is practiced by a significant number of Pashtun people in Pakistan and Afghanistan. The Deobandi diaspora is also found in the United Kingdom and South Africa. The name derives from Deoband, India, where the its first seminary Darul Uloom Deoband was founded in 1867 (Syed et al., Reference Syed, Pio, Kamran and Zaidi2016).

Salafi is an ultraconservative, literalist and censorious branch or movement within Sunni Islam that advocates a return to the traditions of the ‘forefathers’ (the salaf) (Wiktorowicz, Reference Wiktorowicz2006). In its current dominant form, Salafism developed in Arabia in the first half of the 18th century under the leadership of Muhammad ibn Abd-al-Wahhab (hence the term ‘Wahhabi’). He advocated purging practices such as shrine and tomb visitation, declaring these practices to be idolatry, representative of impurities and unlawful innovation in Islam. The Salafis generally inhabit Saudi Arabia, Qatar and UAE but owing to their wealth and the growing network of madrasas and mosques are increasingly influencing ordinary Muslims across the world.

The Deobandis and the Salafis represent a tiny minority within Sunni Islam, estimated to be no more than 5% of the global Sunni population. The majority of ‘ordinary’ people belonging to these two branches are moderate, and reject acts of violence by the extremist factions. Arguably, in terms of their ideologies and practices, such as intolerance of other faith groups and sects within or outside Islam, these subsects are relatively more hardline and pro-Jihadist compared with mainstream Sunni, Shia or Sufi traditions of Islam. The Deobandis and the Salafis are quite similar in their rejection of what they term as bidda (impermissible innovation in religion), shirk (polytheism) and aizdira or tauheen (blasphemy), such as the Sunni and Shia rituals of Milad-un-Nabi (or Mawlid, the Prophet’s birthday) and reverence of Sufi shrines.

In modern discourse, such militancy is also described as takfiri (apostatizing or exclusivist) militancy. A takfiri is an extremist Muslim who accuses other Muslim individuals, groups or entire societies of kufr (infidelity, heresy, blasphemy) due to political, ideological or sectarian differences, and resorts to violence against non-Muslims and other non-takfiri Muslims to enforce a takfiri agenda. In some instances, even moderate Salafis and Deobandis have not escaped violence at the hands of takfiri elements within their own communities (Syed et al., Reference Syed, Pio, Kamran and Zaidi2016).

In the 21st century, takfiri ideology and violence is a known characteristic of extremist sections within Salafi and Deobandi communities. Global Terrorism Index (GTI, 2014) reports that over 80% of the deaths from terrorist attacks in 2013 were in just five countries: Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nigeria and Syria. The report suggests that from 2000 to 2013, four main groups (i.e., the ISIS, Al Qaeda, Taliban and Boko Haram with violent Salafi and Deobandi ideologies) were responsible for 66% of terror-related fatalities across the globe.

Hussain (Reference Hussain2010) analyzed the demographic and religious characteristics of the 2,344 terrorists arrested between 1990 and 2009 in Pakistan. These terrorist cases were the ones forwarded to the courts after the police were satisfied of their guilt based on their preliminary investigation. Hussain’s study shows that Deobandi militants are responsible for more than 90% of terror incidents in Pakistan.

In other words, Muslim communities have significant variances and contradictions among themselves on issues of ideology and its practice. A monolithic understanding of Islam is therefore problematic in the presence of these variants of Muslims, who not only comprehend theology, history and law differently but also breathe a distinctive ethos of faith that cultivates a specific approach and a unique temperament to the very notion of what it means to be Muslim.

The heterogeneity of the Muslim world is not hard to decipher. In 2016, Indonesian, Nigerian and Iranian Muslims protested against the Saudi government in response to the stampede that happened during the Hajj pilgrimage in 2015. These countries and their citizens and organizations protested over mismanagement and the high number of casualties of their pilgrims in the stampede (The Guardian, 2016). Similarly, the recent diplomatic and economic sanctions against Qatar by its fellow Arab countries, including Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Egypt (Wintour, Reference Wintour2017), are further evidence that internal diversity within the so-called Muslim world is hard to ignore.

Notwithstanding this diversity, Western discussions on Islam or on the Arab world are inclined, often implicitly, toward the Sunni interpretation (Nasr, Reference Nasr2007; Fisk, Reference Fisk2017). This inclination is not astonishing, as the vast majority of the world’s Muslim population comprises Sunnis whereas Shias comprise 10–15% of the total 1.3 billion Muslims (Nasr, Reference Nasr2007). However, generally what is presented as a Sunni view is often that of Salafi or Deobandi clerics or organizations who represent a tiny minority within Sunni Islam. In addition, there is significant influence of Saudi- and Qatari-funded lobby groups and think tanks in the West that often present pro-Salafi views and policies as emanating from mainstream Sunni Muslims (Fisher, Reference Fisher2016).

Although Shia Muslims constitute a tiny minority in Southeast Asia and Africa, in the historical heart of the Islamic world, from Lebanon to Yemen, the Shia population almost compares to the Sunni population, and around the geo-strategically sensitive border of the Persian Gulf, Shias constitute almost 80% of the overall population. Again, as Nasr (Reference Nasr2007) asserts, the Sunni version of Islam is not monolithic and consists of Salafi/Wahhabi (dominant in Saudi Arabia, UAE and Qatar), Deobandi (found mostly in South Asia), Barelvi (South Asian version of Sufis) and Sufi (worldwide) Muslims who differ on ideological and jurisprudential grounds.

However, with a monolithic interpretation of Islam, the Shia and Sunni sects tend to be represented as internally homogenous. This is not only problematic but also complicated as the takfiri (exclusivist) or extremist factions within Deobandi and Salafi/Wahhabi communities often take refuge under the Sunni umbrella, to discharge violence against other sects including mainstream Sunnis, Sufis, Shias as well as against non-Muslim communities, including Christians, Hindus, Jews and Yezidis (Moghadam, Reference Moghadam2009; Syed et al., Reference Syed, Pio, Kamran and Zaidi2016). This deliberate appropriation of identity on the part of the takfiri factions is aimed at maintaining power and sharing identity with the majority sect, as well as at creating divides between the otherwise peaceful mainstream Sunni and Shia Muslims or between Muslims and non-Muslims.

An example of this appropriation and obfuscation of identity is the renaming of the banned Pakistani Deobandi terrorist group Sipah-i-Sahaba Pakistan to Ahle-Sunnat Wal-Jamaat (ASWJ). Sipah-i-Sahaba Pakistan was responsible for mass murders and target killing of Sunni Sufi and Shia sects and is banned in Pakistan and other countries (Tan, Reference Tan2010). Its leaders, however, relaunched the group with the name Ahle-Sunnat Wal-Jamaat, thus misappropriating the formal and generic title of the Sunni sect. Mainstream Sunni (Barelvi) organizations protested this fraudulent use of their generic name by a banned terror group. However, the Ahle-Sunnat Wal-Jamaat continues to operate with the new name despite being legally banned in Pakistan (Tanoli, Reference Tanoli2016).

Another example of misappropriation is the very name ‘Islamic State’ used by the violent Salafi terror group (Islamic State in Iraq and Syria aka ISIS) that has killed tens of thousands of innocent Sunni and Shia Muslims, Christians, Yezidis and other communities in the Middle East and other parts of the world. Problematically, in many sections of the Western media, the group is often described as an Islamist or Sunni militant group, thus obfuscating its true doctrinal identity and motivations under sweeping, generic and misleading titles. Indeed, ISIS’s goal of establishing worldwide Islamic caliphate is in fact its agenda of enforcing its own brutal version of Salafi or Wahhabi hegemony over all people including Muslims and non-Muslims.

Problems with a homogenous discourse on islam

Historically enfolding and interpreting diverse understandings of Islamic thought under a single umbrella is problematic for several reasons. First, it reinstates the violent takfiri agenda that there is one mainstream Islam and any other interpretation of the Islamic discourse is heresy (Syed et al., Reference Syed, Pio, Kamran and Zaidi2016), and at the same time, denies importance to the significance of its potential implications on the global economic, social, cultural, organizational and individual levels.

Second, it is problematic in terms of identity management on the part of individuals and organizations. Adida, Laitin and Valfort (Reference Adida, Laitin and Valfort2016) observe that the Muslim community fails to integrate in Christian-majority countries due to the fear of discrimination and the contested idea of Islamophobia. They assert that it is understood and widely accepted that post-9/11, Muslims face discriminatory behaviors in their everyday lives, both in work and nonwork settings (Adida, Laitin & Valfort, Reference Adida, Laitin and Valfort2016). However, Erdagöz (Reference Erdagöz2016) notes that despite a meticulous research design based on repeated experiments, surveys and ethnographic interviews, Adida et al. do make some overarching conclusions. For example, Erdagöz (Reference Erdagöz2016) notes that the sample of Adida et al.’s study consisted of Senegalese Muslim immigrants in France, who are hardly representative of all Muslims. However, we argue that integration of liberal Muslim individuals and communities in Western societies and organizations is less of an issue or challenge than integration of hardline Salafi and Deobandi individuals or groups.

In a similar vein, Syed et al. (Reference Syed, Pio, Kamran and Zaidi2016) contend that what is referred to as Islamic militancy is mostly Salafi or Deobandi militancy, whereas all Muslims might identify with the nomenclature of ‘Muslim,’ they vehemently condemn violence and takfiri ideology in the name of Islam. Yet, they cannot escape the discrimination on the grounds of being Muslims, often in reprisal to violent attacks by takfiri Islamist groups of Salafi and Deobandi origins. Managers concerned about religious discrimination against Muslims need to understand that the basis against which discriminatory practices have arisen cannot be associated with all Muslims alike. Thus, a prudent understanding can create a more inclusive work environment and facilitate the delineation of affirmative action in response to discrimination against Muslims, especially in situations where such affirmative action faces hostility or opposition (Qazi, Reference Qazi2015).

Third, different interpretations of Islamic thought have a direct impact on culture and contextual components and different groups of Muslims have distinct approaches toward life in general. For example, ultraorthodox members of Salafi and Deobandi communities have a radical and literalist approach toward the Quran and Hadith (traditions of Prophet Muhammad) and propagate puritanism (Rajashekar, Reference Rajashekar1989; Azra, Reference Azra2005). In contrast, mainstream Sunni, Shia and Sufi Muslims are more open to symbolism as can be observed through the practices performed on the Prophet’s birthday, that is, reciting Naats (poetry in praise of the Prophet) and playing Daf Footnote 2 ; or on Ashura, that is, weeping, wearing black clothes, recreating historic scenarios and so on (Nasr, Reference Nasr2007).

Implications for management, organizations and governance

This heterogeneity within Islam has important implications from the perspective of management, organizations and governance. Multinational corporations may need to understand that in their international operations in the Middle East and other Muslim majority regions, countries and communities, they are interacting with a range of ideologies. For example, in Saudi Arabia, Qatar and UAE, multinational corporations are likely to be dealing with Salafi and Hanbali ideology of the state,Footnote 3 while in their operations in Egypt, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Turkey, it is likely to be Sunni Hanafi ideology (Knysh, Reference Knysh2007; Johnson & Vriens, Reference Johnson and Vriens2011). Similarly, in their operations in Iran, Iraq, Azerbaijan and the northern part of Yemen, they are dealing with Shia (Jafari or Zaidi) ideology, in Indonesia and Malaysia, they mainly encounter Shafii ideology, and in North Africa, they are mostly faced with Maliki ideology (Mayer, Reference Mayer1995; Nasr, Reference Nasr2007).

Though individual practices may vary, puritanical and literal interpretations and intolerance of religious and gender diversity are identifiable attributes of hardline sections within Salafi and Deobandi communities. In the West, these attributes are evident in communities affiliated or exposed to Saudi, Emirati or Qatari-funded mosques, seminaries, pamphlets and related literature. Such practices lead to ghettoization and isolation of these communities from mainstream society with strict rules of gender segregation and female seclusion (Mir & Naquvi, Reference Mir and Naquvi2016).

In addition, organizations may not realize important differences within Muslim communities with respect to practices of gender segregation, female seclusion, female circumcision and approaches to ethnic and religious diversity. This is evident in relatively less restrictions on women’s mobility and employment in Hanafi-dominated Turkey and Pakistan as compared with Salafi- or Wahhabi-dominated Saudi Arabia. In Pakistan, the presence of women at Sufi shrines and festivals is in stark contrast to strict norms of gender segregation and female seclusion in practicing Deobandi and Salafi communities. Similarly, the presence of sizable Jewish population in Shia-dominated Iran is in stark contrast to elimination of entire Jewish population from the Salafi/Wahhabi-dominated Saudi Arabia and many other countries in the Middle East (Sengupta, Reference Sengupta2016).

When Muslims travel from their source countries to immigrate and/or work in Western countries or typically in non-Muslim majority countries, they carry with them their traditions and ways of being, not only into the receiving countries’ societies but also into the organizations situated in these countries. Add to this, the influx of refugees into Europe, many of whom are Muslims, from countries such as Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq and Somalia and the complexity of the management and diversity of the workforce within an organization increases exponentially.

Although such diversity can be viewed as an ominous challenge, it is also a multifarious opportunity to share the richness of the threads that unite humanity and for organizations to serve as leaders, nurturers, path-breakers and path-creators in forging sophisticated talent management and growth opportunities. Indeed, if we hark back to the period when Islam was known for its scientific advancements and humane treatment of all societies, we note that the Ottoman Empire welcomed Jews when they were persecuted in many parts of Europe (Fatah, Reference Fatah2011). Furthermore, during the Irish potato famine in the 19th century, the Ottoman Caliph Abdul Mejid wanted to contribute 10,000 pounds but was requested by Queen Victoria not to contribute this amount, as that would overshadow her contribution of 2,000 pounds (Hayes, Reference Hayes2016). In the Indian subcontinent, we have the example of the 16th century Mughal Emperor Akbar who institutionalized and implemented a pluralist policy of the sulh-e-kul (absolute peace) for people of diverse faiths and sects (Syed, Reference Syed2011).

In terms of denominational diversity, there are varied approaches to community leadership. For example, in Sunni Islam, the first four caliphs (the rashidun) are most prominent after the Prophet Muhammad, and after them importance is accorded to the four Imams of jurisprudence (Abu Hanifa, Malik, Shafii and Ahmed ibn Hanbal) (Makdisi, Reference Makdisi1979). In contrast, in Shia Islam, Prophet Muhammad and his 12 descendants (12 Imams) are considered the legitimate spiritual leaders (Abdal-Haqq, Reference Abdal-Haqq2002). In the modern era, the institution of taqleed or followership (in religious matters) of a competent cleric is an integral part of the Twelver Shia ideology (Akhavi, Reference Akhavi1988). In contrast, in Sunni Islam, there is no such central authority and as such different clerics, organizations and countries use their own influence to direct and indoctrinate Sunni Muslims (Ruthven, Reference Ruthven2012). In the absence of central control, there is thus a possibility within organizations and wider society that some Muslim and non-Muslim individuals may be influenced by radical ideologies of extremist groups.

There are also financial implications of such differences. For example, in Sunni Islam, zakat (2.5% religious tax on total savings and wealth) may be given to any needy person or community based on the donor’s discretion, whereas in Shia Islam an additional khums tax (20% of all gains and profits) is mandatory, which must be distributed through a competent cleric (Mallat, Reference Mallat1988; Karim, Reference Karim2014).

There are further distinctions within Islam. For example, Sufi Muslims (within Sunni and Shia sects) pay special attention to the construction and maintenance of shrines and there are legal trusts or awqaf registered for management of these buildings and funds, and contribute to public welfare (Green, Reference Green2004). In contrast, in ultraorthodox Salafi and Deobandi traditions, shrines are not permissible and must be leveled to the ground. Some members of these ultraorthodox traditions seem to endorse violence and attacks on Islamic shrines (often maintained and managed by Sunni, Sufi and Shia Muslims) (Fair, Reference Fair2011). Frequently, many mainstream Sunni, Shia and Sufi practices and religio-cultural rituals are described as bidda (unlawful religious innovation) and shirk (polytheism) by Salafi and Deobandi clerics and extremist groups.

On a global scale, radical Salafi and Deobandi groups may indulge in practices of intolerance and discrimination directed against women and/or religious and ethnic minority groups within or outside Islam (Fair, Reference Fair2011; Syed et al., Reference Syed, Pio, Kamran and Zaidi2016). This may result in particular gender discriminatory and exclusionary practices and laws, for example, restrictions in Saudi Arabia on women’s driving and independent mobility. In contrast, some interpretations of Islam are relatively more pluralistic, such as the presence of people of diverse faiths, ethnicities and gender at Sufi shrines and Ashura (Muharram) rituals (Iraqi News, 2009). In addition, though in somewhat diverse ways, both mainstream Sunni and Shia Muslims practice the rituals of Sufi shrines and Ashura.

In terms of diversity, while there is evidence of commitment to equality – based on gender, ethnicity and race – within several injunctions of the Quran and the Hadith (traditions of Prophet Muhammad), actual practices vary greatly across societies, cultures and organizations (Syed & Pio, Reference Syed and Pio2017). Thus, the status and roles of women in the Salafi/Wahhabi-dominated Saudi Arabia are different to those in Shafii-dominated Malaysia or Hanafi-dominated Turkey and Pakistan (Kandiyoti, Reference Kandiyoti1991). With respect to diversity within Islam, it is important to consider intersectionality of gender with Islamic denomination and ethnicity because these additional layers may greatly shape equal opportunities or lack thereof facing Muslim women (Pio, Reference Pio2010; Syed & Van Buren, Reference Syed and Van Buren2014). Such additional layers may also reflect potential exposure and vulnerability of Muslim women to intolerant and extremist ideologies.

Similarly, the treatment of ethnic minority and migrant workers remains a sore point in the UAE, Qatar and other Gulf countries (Gibson, Reference Gibson2016). Moreover, there seems to be greater commitment to cultural heritage, arts and music in Central and South Asia than in countries dominated by Salafi ideology (Batsh, Reference Batsh2016). There are also disparities because of urban/rural background and regions. These may exist within a single country. For example, in the case of Iran, women in Tehran, the capital city, seem to be relatively more independent and active in everyday life and employment when compared with women in more rural locations such as Qom and Zahedan (Farsian, Reference Farsian2003).

The literalism–symbolism divide is important for organizational contexts because these attitudes have the tendency to be translated into work behaviors (e.g., Ghazal Read, Reference Ghazal Read2004). There is, thus, a need for identification of Muslims not by a monolithic perspective but a more fine-grained understanding of their doctrinal affiliations and practices. The majority of ordinary Muslims may not be able to (or may prefer not to) explain these nuances and internal diversities within Sunni, Shia and other denominations of Islam. Yet, their attitudes toward women and people of diverse faiths and sects within and outside Islam and their approach toward the goal of a worldwide caliphate and elimination of bidda and shirk may reveal their levels of tolerance and integration (or lack thereof). In organizational settings, this would help in developing an informed understanding of different types of Muslims, in ensuring general security within and outside the workplace, and also in creating discrimination-free working environment for the dominant majority of tolerant and peaceful Muslims. Such an approach would also help identify takfiri and potentially violent Muslims who may cause harm to fellow employees. For example, in a shooting incident in St. Bernardino, a ‘Muslim’ couple, Farook and Tashfeen, shot 14 people at Inland Regional Center, a social services agency. Allegedly, one of the 14 victims had an argument with the killer concerning Islam, which agitated the killer into carrying out a morbid act violence (Cabrera, Carroll & Dart, Reference Cabrera, Carroll and Dart2015). The killers are known to have connections with radical Deobandi and Salafi/Wahhabi ideology (Syed, Reference Syed2015). Other news sources claim that the killer was forced to pose for a photograph at a mandatory Christmas dinner, which according to the Federal Bureau Investigation was his potential motive for the shooting (Massarella, Reference Massarella2016). The news article shows the bearded killer Farook posing for the photograph with his arms uncomfortably at his sides. Farook’s purported aversion to Christmas celebrations is an example of his intolerance for symbolism and cultural diversity, which is a characteristic of Salafi and Deobandi Muslims who refer to Christmas celebrations as haram (Taylor, Reference Taylor2009).

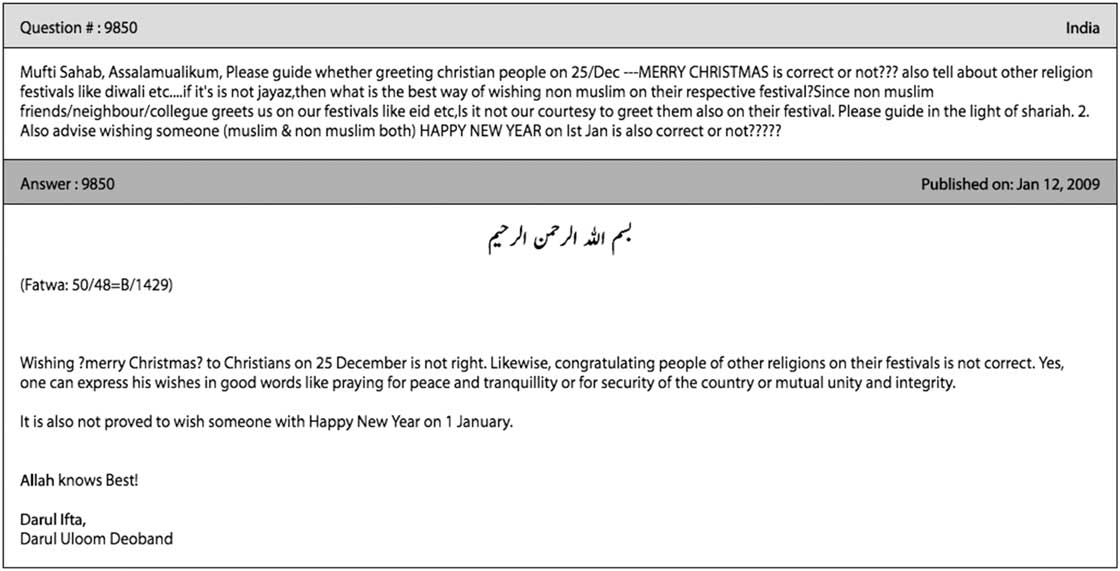

A leading Deobandi cleric Taqi Usmani wrote a detailed article describing the participation of Muslims in Christmas and other similar festivals as forbidden in Islam (Usmani, Reference Usmani2015). In 2009, the Darul Uloom Deoband, the oldest and most credible Deobandi seminary in the world, issued a fatwa (religious ruling on issues pertaining to Islamic law, usually in response to questions by ordinary Muslims) declaring that Muslims were not allowed to wish ‘Merry Christmas’ to Christians. The fatwa also forbade Muslims from congratulating people of other religions on their festivals or to wish someone on New Year. Figure 1 offers a screen image of the fatwa (Darul Ifta Deoband, 2009).

Figure 1 Deobandi fatwa against ‘Merry Christmas’

Such exclusivist fatwas are likely to create isolationist and intolerant attitudes within their circle of influence. In extreme cases, they enable a takfiri mindset. Disagreement and alternate understandings of theology and conduct are despised by takfiris who display intolerant and misogynistic behaviors pertaining to anything other than their version of religion. In another incident, a ‘Muslim’ named Omar Mateen shot 49 people at a gay club in Orlando (Spargo, Reference Spargo2016). According to his co-workers, Omar was a rage-filled homophobe who uttered nasty words at the sight of women and people of color.

In yet another incident of faith-based violence in the workplace, Nidal Hasan, a US Army major and psychiatrist, fatally shot 13 people and injured more than 30 others in a mass shooting at Fort Hood, TX, USA in November 2009. According to the news reports, he was indoctrinated by Anwar al-Awlaki, an Al-Qaeda-affiliated cleric (Memri, 2009).

In all of the above examples, the news from mainstream media did not mention doctrinal or jurisprudential affiliations of the killers, while mentioning them as Muslims. Having established the notion that ‘Muslim’ is not a monolithic title, such journalism and research can be described as misleading and problematic for both organizations and mainstream Muslim employees.

Overview of papers

The papers included in this special issue of ‘Journal of Management and Organization’ are the first attempt in scholarly literature to focus on internal heterogeneity of Islam and outline its implications for management and organizations. An overview of the papers selected for this issue is provided in this section.

In their paper titled, ‘The diversity of professional Canadian Muslim women: Faith, agency, and “performing” identity,’ Latif, Cukier, Gagnon and Chraibi examine how identities are constructed and performed by Muslim women in the Canadian workplace. Their study provides fresh insights on how these women disclose or ‘perform’ their identities in different contexts. Drawing on interviews with 23 professional Muslim women in Canada, the study builds on and adds to the literature on identity construction of ethnic minorities, intersectionality and the workplace experiences of Muslim women. The authors discuss important implications for understanding Muslim women’s identity work in broader contexts of discrimination as well as accommodation and inclusion in organizations.

Next paper in this special issue is titled, ‘Contextualizing comprehensive board diversity and firm financial performance: Integrating market, management and shareholder’s perspective.’ In this paper, Hassan and Marimuthu examine demographic, cognitive diversity and internal diversity within Islam at the top level of management and its impact on financial performance of Malaysian-listed companies. The study also examines Muslim and non-Muslim women and religious diversity on corporate boards. Data from 330 Malaysian-listed companies in 11 full-fledged sectors were used for the period from 2009 to 2013. The study used econometrics methodology from panel data analysis to fill the research gap in the current management literature. The study used the interaction approach to examine empirically diverse corporate boards and their impacts on firm performance. This discussion included: (1) a combination of gender diversity and ethnic diversity and (2) the combination of gender diversity with foreign participation. The findings suggest that demographic, cognitive and internal diversity within Islam are significant predictors of a firm’s financial performance. Ethnic women on boards have a significant and negative impact on firm performance. Hence, companies having high profits are more accountable for encouraging diversity among top-level management.

In their paper titled, ‘“Good Muslim women” at work: An Islamic and postcolonial perspective on ethnic privilege,’ Ali and Syed argue that within sparse studies available on ethnic privilege at work, the emphasis is dominantly on ethnic privileges available to white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant, heterosexual men and, to a lesser extent, white women. Their paper presents and develops an Islamic and postcolonial perspective on ethnic privilege, which is unique not only due to contextual and cultural differences but also due to its postcolonial nature and composition. By postcolonial, the authors refer to cultural legacies of Arab colonialism and ideology in South Asia and elsewhere. Drawing on a study of Muslim female employees in Pakistan, the authors show that religio-ethnic privilege represents postcolonial influences of a foreign (Arab-Salafi, ultraorthodox Islamist) culture on a non-Arab Muslim society, and as such does not represent ethnic norms of a local mainstream society. The paper investigates the case of religio-ethnic privilege and female employment in Pakistan and examines how a foreign-influenced stereotype used to benchmark “good Muslim women.”

Finally, in their paper titled, ‘Entrepreneurship as worship: A Malay Muslim perspective,’ Sidek, Pavlovich and Gibb focus on variations in the interpretations of Islamic law (i.e., Sharia). The authors argue that this variation may hold the key in explaining the different behaviors among Muslim entrepreneurs because of their views on the concept of work as worship. In their study, they examine how Malay entrepreneurs are guided in their sourcing and shaping of entrepreneurial opportunities through the Shaffi school of jurisprudence. The authors identify five central values that guide the participants’ sourcing of opportunities: Fardhu Kifayah (communal obligation), Wasatiyyah (balanced), Dakwah (the call of joining the good and forbidding the bad), Amanah (trust) and Barakah (blessings). Their study contributes to the entrepreneurship literature by demonstrating how these macro-level values of worship give the entrepreneurs confidence in creating their new ventures.

Agenda for future research and concluding comments

In this special issue, we have sought to introduce the concept of heterogeneity within Islam to organizational and management studies literature. However, much research still awaits this domain. Future researchers may conduct detailed empirical investigations of Muslims of various types and the implications of such diversity for organizations and societies. There is also need for ethnographic studies that investigate the psychological patterns and work habits that underlie intolerance inside and outside workplaces.

Associating acts of intolerance and violence to all Muslims has had negative impact on many peaceful Muslims (TRT World, 2016). Post 9/11, incidents of violence and discrimination against Muslims have resulted with the ascendance of Islamophobia, and its implications are faced by all Muslims regardless of their sect or involvement in any intolerant or violent activity. Individuals have multiple identities and in order to incriminate a culprit, it is important to pinpoint the precise ideology that instigated the particular crime. Muslim is a large identity shared by various, different groups of people; it is thus important to identify the variant of Islam or Muslim that tends to preach or promote intolerance or violence.

Our call for further scholarship on this topic delves into the ideological and cultural contexts, as well as the past, present and future as a lens, for a more erudite and refined understanding and interpretation of Islamic heterogeneity in the context of management and organizations. This call is especially important given the lack of studies that engage with the diversity and complexity in various kinds of organizations, diverse theoretical frameworks, methodologies and ensuing management practices, which highlight the heterogeneity within Islam. There is, therefore, a need to take a contextual perspective, whether it be positioning Islam, culture and history or management and organizations as context (Härtel & O’Connor, Reference Härtel and O’Connor2014).

Through this editorial and special issue, we have provided a glimpse of the ideological and cultural heterogeneity of Islamic thought and alluded to its implications for management and organizations. We have also put out a clarion call for further research to investigate various types of Islam and Muslims and their inherent differences and potential organizational implications of these differences. Given the dearth of research on context in organizational behavior (Jones, Reference Johns2006), scholarship that contextualizes Islam and Muslims is vital for a more refined and less clumsy understanding of this important aspect of religious diversity in organizations and societies.

Through a nuanced understanding of heterogeneity within Islam, we can engage with the dominant majority of peaceful Muslims in mutually productive and inclusive ways within and outside the workplace. Moreover, extremist ideologies and radicalized subsects that represent only a tiny minority of Muslims and pose challenges to security, diversity and peaceful co-existence can be more astutely understood. In academic scholarship and media projections, it is important to clearly identify and separate such extremist ideologies and communities from the majority of peaceful Sunni and Shia Muslims. As a final word, it is instructive to remember that Islam means peace.