Introduction

Leadership research consistently indicates that leaders engage in differing behaviours in the process of influencing their followers (see Gooty, Thomas, Yammarino, Kim, & Medaugh, Reference Gooty, Thomas, Yammarino, Kim and Medaugh2019; Graen, Haga, & Ingersoll, Reference Graen, Haga and Ingersoll1975; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Yammarino, Dionne, Eckardt, Cheong, Tsai and Park2020; Little, Gooty, & Williams, Reference Little, Gooty and Williams2016). Referred to as leader–member exchange (LMX) (Graen, Haga, & Ingersoll, Reference Graen, Haga and Ingersoll1975), the quality of this relationship results in different outcomes. For example, the leader–member relationship quality is associated with followers' job satisfaction (Fisk & Friesen, Reference Fisk and Friesen2012), intention to stay in the organization (Bang, Reference Bang2011; Scandura & Graen, Reference Scandura and Graen1984) and organizational citizenship behaviour towards the organization (Chan & Mak, Reference Chan and Mak2012; Lee, Thomas, Martin, Guillaume, & Marstand, Reference Lee, Thomas, Martin, Guillaume and Marstand2019). While leadership research has paid significant attention to the role of leadership on the quality of subordinates' LMX experience, evidence from a meta-analysis study on antecedents and outcomes of LMX shows that much more attention needs to be focused on the leaders' perception of LMX (Dulebohn, Bommer, Liden, Brouer, & Ferris, Reference Dulebohn, Bommer, Liden, Brouer and Ferris2012).

Similarly, research has scarcely explored the leader's behaviour as an important antecedent in the LMX relationship, thus making it difficult to identify how leaders influence this dyadic relationship (O'Donnell, Yukl, & Taber, Reference O'Donnell, Yukl and Taber2012). The lack of knowledge of the leader's behaviours that impact the LMX quality is problematic. In this respect, earlier studies have focused on the use of transformational leadership component as a surrogate for leader behaviours in an LMX relationship. While there is evidence that specific transformational leadership component behaviours have different effects on LMX, these differences disappear when only the meta-category is used in an analysis (see Deluga, Reference Deluga, Clark, Clark and Campbell1992). Furthermore, O'Donnell, Yukl, and Taber (Reference O'Donnell, Yukl and Taber2012) suggest that failure to include certain leadership behaviours that are likely to influence LMX but not in the measure of transformational or transactional leadership compounds the interpretation of a significant correlation between transformational leadership and LMX. Likewise, research findings in a meta-analytic study suggest that transactional leadership is a ‘double-edged sword’ when predicting follower performance in an LMX relationship. For example, contingent reward fosters LMX but hinders empowerment, whereas management by exception fosters empowerment but hinders LMX (see Young, Glerum, Joseph, & McCord, Reference Young, Glerum, Joseph and McCord2020).

Moreover, and until recently, leadership research seems to have largely omitted the role of followership in the leadership process (Gooty, Connelly, Griffith, & Gupta, Reference Gooty, Connelly, Griffith and Gupta2010). Ford and Harding (Reference Ford and Harding2018) contend that little research appears to have examined the role of followers' characteristics when considering the quality of LMX relationships. Indeed, we are aware that both leaders and followers form perceptions of their dyadic partner and that these perceptions influence the leader's and follower's perceptions and reactions to the LMX relationship (Giessner, Van Quaquebeke, Van Gils, Van Knippenberg, & Kollée, Reference Giessner, Van Quaquebeke, Van Gils, Van Knippenberg and Kollée2015; Tsai, Dionne, Wang, Spain, Yammarino, & Cheng, Reference Tsai, Dionne, Wang, Spain, Yammarino and Cheng2017). Tsai et al. (Reference Tsai, Dionne, Wang, Spain, Yammarino and Cheng2017), for example, demonstrate that expressive relational schema congruence has a positive effect on follower-rated LMX, while instrumental relational schema congruence has a negative effect on follower-rated LMX.

Additionally, the interactions between a leader and a follower are not void of emotions because leaders convey meanings through emotions that may need to be regulated from time to time (Fisk & Friesen, Reference Fisk and Friesen2012; Little, Gooty, & Williams, Reference Little, Gooty and Williams2016). We argue that leader's and follower's perceptions of each other are emotionally driven. In this regard, Silard and Dasborough (Reference Silard and Dasborough2021) theorize that leader emotions have disparate effects on followers in high- and low-quality leader–member relationships, depending on whether the emotions are directed externally towards followers, or self-directed towards the leader. Along the same lines, Gooty, Thomas, Yammarino, Kim, and Medaugh (Reference Gooty, Thomas, Yammarino, Kim and Medaugh2019) argue that the convergence in positive and emotional tone in leader–follower relationships would affect the reciprocity based on LMX reported by both parties. They found support largely for convergence in positive emotional tone but not supported for convergence in negative emotional tone in LMX relationships. Nevertheless, one question that remains unanswered is how a leader's and follower's perception of their dyadic partners behaviours may impact the dyadic relationship and how emotional regulation may buffer this relationship and a leader's rating of LMX quality. To address this problem, we argue that the leader's perception of a follower's behaviours may impact the follower's perception of a leader's behaviours and that this, in turn, may impact the leader's rating of their LMX quality. Additionally, we investigate the joint effect of the leader's perception of follower's behaviours (and vice versa) and leader's emotional re-appraisal on the leaders rated LMX quality.

Furthermore, there is evidence that leaders and followers mutually construct their dyadic relationship and come to expect certain behaviours in that relationship (Fisk & Friesen, Reference Fisk and Friesen2012). Studies in social exchange suggest that when these expectations are not met in a relationship, individuals are expected to be dissatisfied (Dulebohn et al., Reference Dulebohn, Bommer, Liden, Brouer and Ferris2012) and are less likely to ‘give back’ (Fisk & Friesen, Reference Fisk and Friesen2012). We argue that the extent to which a leader and follower meet the expectations of each other may be foundational to their perceptions of each other's behaviours (Berkovich & Eyal, Reference Berkovich and Eyal2021; Gooty et al., Reference Gooty, Thomas, Yammarino, Kim and Medaugh2019). We further argue that perceptions are related to behaviours (Ng, Yam & Aguinis, Reference Ng, Yam and Aguinis2019) and thus we propose that a follower's perceptions of his/her leader's behaviours (i.e., as revealed through attitudes and behaviours) might determine how the leader also perceives the follower and subsequently their LMX relationship. So far, few studies are focused on how the perceptions of the leaders (supervisors) by their followers (subordinates) contribute to the leaders' behaviours and his/her rating of the LMX quality (Chen, Lam, & Zhong, Reference Chen, Lam and Zhong2012). The answer to the above question should deepen our understanding of the role of the follower's perceptions of his/her leader's behaviours in the leadership–followership process and more specifically, how the follower perceives and interprets a leader's actions and behaviours, may impact the leader's perceptions of LMX quality.

In the current research, we focus on the effect of the leader's and follower's assessment of each other (Ehrhart & Klein, Reference Ehrhart and Klein2001; Xu, Loi, Cai, & Liden, Reference Xu, Loi, Cai and Liden2019) and we argue that at the dyadic level, both leader's and follower's perceptions of their dyadic partner may create a psychological vantage point from which the leader and the follower may evaluate each other in an LMX relationship. Thus, the LMX quality is likely to be driven by the leader's and follower's assessment of their dyadic partners. Overall, research examining the effect of a leader's and follower's assessment of each other in the process that culminates into LMX rating is sparse.

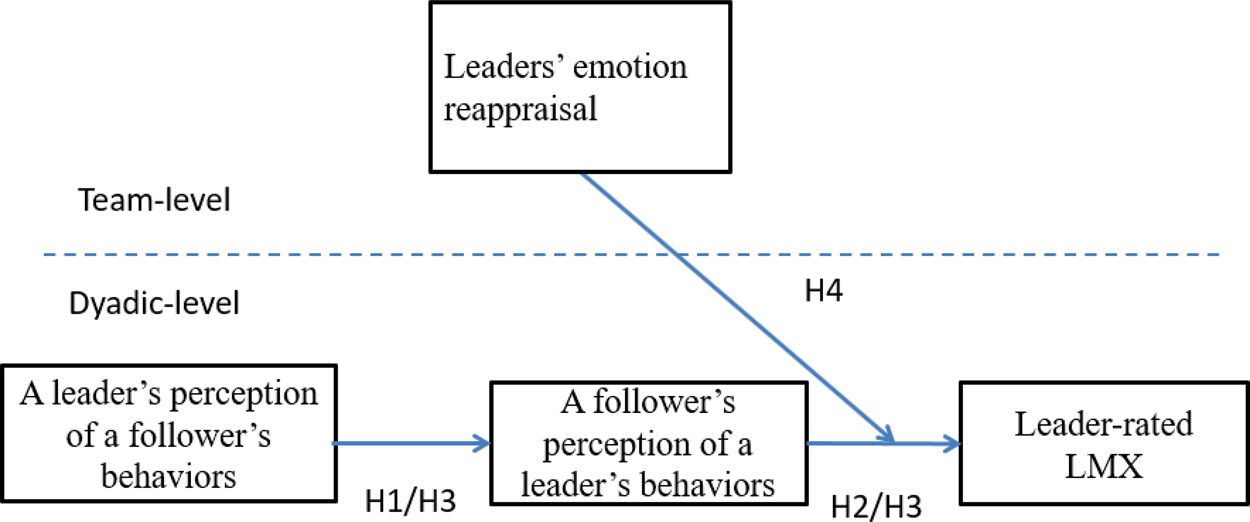

Moreover, an increasing amount of research interest has targeted the role of emotions (defined as a discrete and intense but short-lived experiences that are reactions to a stimulus and lead to a range of possible consequences, Forgas, Reference Forgas1995; see also Angie, Connelly, Waples, & Kligyte, Reference Angie, Connelly, Waples and Kligyte2011; Gooty et al., Reference Gooty, Thomas, Yammarino, Kim and Medaugh2019; Moin, Wei, Weng, & Ahmad Bodla, Reference Moin, Wei, Weng and Ahmad Bodla2021) in leadership (Glasø & Einarsen, Reference Glasø and Einarsen2008; Gooty et al., Reference Gooty, Thomas, Yammarino, Kim and Medaugh2019; Gooty et al., Reference Gooty, Connelly, Griffith and Gupta2010). Although there is evidence to suggest that a powerful affective bond is fundamental to the development of high-quality LMX (Liden, Wayne, & Stilwell, Reference Liden, Wayne and Stilwell1993), relatively less emphasis has been placed on exploring the antecedents of LMX (see Cropanzano, Dasborough, & Weiss, Reference Cropanzano, Dasborough and Weiss2017; Sears & Holmvall, Reference Sears and Holmvall2010; Sears & Hackett, Reference Sears and Hackett2011). While researchers (e.g., Gooty et al., Reference Gooty, Thomas, Yammarino, Kim and Medaugh2019; Moin et al., Reference Moin, Wei, Weng and Ahmad Bodla2021) have focused on emotions and affective processes in leadership and LMX relationships, less emphasis appears to have been placed on the role of the leaders' emotional regulation and how it might impact their rating of LMX in a dyadic relationship (for an exception Fisk & Friesen, Reference Fisk and Friesen2012; Moin et al., Reference Moin, Wei, Weng and Ahmad Bodla2021). To fill this research gap, we explore the moderating role of leaders' emotional regulation in the relationship between follower assessment of the leader and the leader rated LMX. Thus, consistent with LMX theory, we build a cross-level model that explains the processes by which leaders' interpersonal perception of his/her current follower's behaviours may, in part, drive the followers' interpersonal perception of the leaders' behaviours which may eventually impact the leaders' rating of LMX quality (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. A cross-level model of the leader–follower interpersonal cognitive assessment, emotions and LMX.

Altogether, we contribute to the advancement of research in leader's/follower's characteristics (e.g., the perception of their dyadic behaviours), the leader's emotions (e.g., emotional reappraisal) and LMX in three important ways. First, existing literature demonstrates that a follower's perception may be developed from previous dyadic experiences with a leader (Epitropaki & Martin, Reference Epitropaki and Martin2005). In the current research, we specifically build and test a model that suggests that the leader learns and interprets his/her current follower's behaviours and that these behaviours, in turn, drive the follower's perceptions of the leader thereby extending work in the leader–follower relational evaluation.

Second and as earlier established, the role of follower characteristics in the leadership process has relatively been ignored (Howell & Shamir, Reference Howell and Shamir2005). By investigating the role of the follower's perception of his/her leader's behaviours and how it may be connected with a leader's perception of LMX quality, we might be able to clarify how followers contribute to the leadership process (Ehrhart & Klein, Reference Ehrhart and Klein2001; Fisk & Friesen, Reference Fisk and Friesen2012).

Third, scholars (e.g., Fisk & Friesen, Reference Fisk and Friesen2012) have just begun to explore the role of emotional regulation (i.e., reappraisal see Gross, Reference Gross1998; Gross & John, Reference Gross and John2003) in the context of LMX. Specifically, we conceptualize emotional reappraisal/regulation (the process by which individuals influence the emotions they have, and when and how they experience and express these emotions; Gross, Reference Gross1998) as an important variable that has the potential to moderate the relationship between the follower's interpersonal evaluation of their interpersonal interactions and the leader's perception of LMX quality (see Figure 1). In this regard, we propose that the leader's emotional regulation (e.g., emotional reappraisal) is a key determinant in their perception of the LMX quality. Our aim is to tease out and provide insights into how emotional regulation (i.e., reappraisal) may potentially impact the leaders' evaluation of a dyadic LMX relationship. By so doing, we extend research that explicates leaders' emotions in an LMX relationship (Vidyarthi, Liden, Anand, Erdogan, & Ghosh, Reference Vidyarthi, Liden, Anand, Erdogan and Ghosh2010).

Theoretical background and hypotheses development

Leader–member exchange theory

Grounded in role theory (Katz & Kahn, Reference Katz and Kahn1966), the LMX theory evolves from the vertical-dyad linkage (Dansereau, Graen, & Haga, Reference Dansereau, Graen and Haga1975). Proponents of LMX theory posit that the leadership process occurs when leaders and members assume their respective roles to interact and develop dyadic relationships through relational exchanges (Graen & Scandura, Reference Graen, Scandura, Staw and Cummings1987; Graen & Uhl-Bien, Reference Graen and Uhl-Bien1995). LMX theory proposes that leaders do not treat all followers identically; rather, they develop different relationships with their followers (Boies & Howell, Reference Boies and Howell2006; see also Wu, Tse, Fu, Kwan, & Liu, Reference Wu, Tse, Fu, Kwan and Liu2013) that are qualitatively different in quality and this, in turn, leads to a variety of outcomes relevant to employees, teams, organizations (Gerstner & Day, Reference Gerstner and Day1997; Herdman, Yang, & Arthur, Reference Herdman, Yang and Arthur2017) and the leaders. More specifically, this differentiated LMX relationship develops through three phases: (1) role taking – where members are evaluated based on his/her abilities and talents; (2) role making – when a member's performance and leader's delegation interact to formalize relationships and create roles; and (3) role routinization – when the LMX relationship becomes affect-laden as a result of ongoing social exchange between the leader and member (Graen & Scandura, Reference Graen, Scandura, Staw and Cummings1987). Graen, Dansereau, and Minami (Reference Graen, Dansereau and Minami1972) contend that these differences between each member's perceptions of their leader reflect valid differences in the quality of the leader–member relationship and that these valid differences may be explained by relational expectation theory.

Leader and follower perceptions of each other's behaviours

We propose that leader's and follower's perceptions of each other's behaviours are also possible through sense making and sense giving (see Kraft, Sparr, & Peus, Reference Kraft, Sparr and Peus2018; Weick, Reference Weick1993). Sense making and sense giving, in turn, may influence the relationship partner. In this respect, we argue that the perceptions of a leader about his/her follower in an LMX relationship may be passed on the follower through sense giving (Weick, Reference Weick1993). For example, a leader whose evaluation of his/her follower's behaviours in an LMX relationship is negative may rate his/her follower's performance appraisal low or deny him/her promotion. In this case, the leader's behaviours may signal to the follower the perception of his/her leader. Thus, through the process of sense-giving, the leader may express (implicitly or explicitly through his/her feelings, attitudes and behaviours) his/her negative perceptions of the follower to the follower. Thus, we argue that by making his/her perceptions of the follower known through sense giving to the followers, the perceptions of the followers about the leader may also be formed. The perceptions formed by the follower given the leader's feedback on the attitudes and behaviours of the follower may thus impact how the followers perceive their leaders and may explain the variability in the followers' assessment of the leader's behaviour. Nahrgang, Morgeson, and Ilies (Reference Nahrgang, Morgeson and Ilies2009) argue that in subsequent exchanges, followers and leaders assess each other to determine whether they can build relational components that will allow the development of a high-quality exchange (see also Chen, Huo, Lam, Luk, & Qureshi, Reference Chen, Huo, Lam, Luk and Qureshi2021).

Furthermore, the leadership/followership process is interdependent and interrelated such that in a dyadic relationship, followers depend on leaders to accomplish goals thus making it imperative for followers to continue to actively make sense of their relationship with their leaders (Dulebohn et al., Reference Dulebohn, Bommer, Liden, Brouer and Ferris2012) and vice versa. Follower's sense making of LMX may include his/her desire to gain feedback on how he/she is being perceived by his/her leaders (Lord & Maher, Reference Lord and Maher1991; Sin, Nahrgang, & Morgeson, Reference Sin, Nahrgang and Morgeson2009). For example, a leader who has a negative perception of his/her follower's behaviours and delivers a poor performance appraisal rating to the follower has passed a message to the follower. This message to the follower about his/her poor performance may, in turn, influence the follower's perceptions of the leader. In this situation, the message to the follower about his/her poor performance (through the leader's sense giving) may make the follower think, interpret and evaluate how his/her leader has managed him/her, thus influencing the follower's perceptions of the leader's behaviours. The ongoing discussion suggests that a leader's perception of the follower's behaviours in a dyadic relationship also has a potential to impact the follower's perceptions of the leader. Altogether, we argue that the leader's perceptions of the follower in a dyadic relationship may be a key driver of the follower's assessment of his/her leader. Thus:

Hypothesis 1: In a dyadic relationship, a leader's perceptions of his/her follower's behaviours are related to the follower's perceptions of his/her leader's behaviours.

Followers' evaluation of his/her leader's behaviours and leaders' perception of the LMX quality

Leadership is a dynamic and two-way exchange between leaders and followers who can mutually influence each other (Shondrick & Lord, Reference Shondrick, Lord, Hodgkinson and Ford2010). In the leadership situations, it is not only leaders' perceptions that could potentially influence followers' perceptions as proposed in Hypothesis 1, but also followers' perceptions could influence leaders' judgements and perceptions. In this regard, the rationale of sense making and sense giving described above also applies in the follower-to-leader relationship. When followers have a positive perception of their leaders, they will display higher level of respect for leader and rate leader effectiveness more positively (Van Quaquebeke, Van Knippenberg, & Brodbeck, Reference Van Quaquebeke, Van Knippenberg and Brodbeck2011) as well as demonstrate positive emotions such as happiness (Kruse & Sy, Reference Kruse and Sy2011). Leaders can make sense of followers' positive view and endorsement of the leaders. Similarly, leaders can sense followers' positive emotions towards leaders and consequently assess their LMX more favourably. Conversely, followers who are less satisfied with their leaders' behaviours could elicit negative emotions such as sadness and anger (Kruse & Sy, Reference Kruse and Sy2011) and even act disrespectfully to the leader or challenge the leader. This may consequently trigger leaders' increased negative assessment of their LMX relationship. Thus:

Hypothesis 2: A follower's perceptions of his/her leader's behaviours are positively related to the leader's evaluation of LMX quality.

Follower's perceptions of the leader's behaviours as a mediator in the link between the leader's perceptions of their follower's behaviours and leader's LMX rating

We argue that the follower's perceptions (e.g., of the leader's behaviours) may be an intervening variable in the link between leaders' perceptions (of the follower) and leaders' rating of their dyadic LMX relationship. In this respect, we suspect that follower's perceptions of the leader's behaviours may partly explain the leader's rating of his/her LMX. This is because we know that there is a link between perception and behaviour which is developed based on repeated observations of co-activation (Feldman, Reference Feldman1981). In this case, repeated co-activation of the perception and behaviour of a follower (especially after his/her cognitive assessment) may eventually crystalize into actions and behaviours that may finally impact the leaders' behavioural response such as the evaluation of LMX.

Similarly, and based on sense making and sense giving (Weick, Reference Weick1993) the way in which leaders and followers interpret each other's behaviours is impacted (Van Gils, Van Quaquebeke, & Van Knippenberg, Reference Van Gils, Van Quaquebeke and Van Knippenberg2010). In this instance, a leader with a positive perception of his/her follower's behaviours will most likely elicit a positive perception from his/her followers. Given exchange theory, this positive perception is expected to influence the quality of the dyadic relationship between the leaders and followers such that a leader whose behaviours are positively perceived by the follower and perceived to be liked by the follower will also be more generous in rating their LMX.

In contrast, a leader whose behaviours and actions are negatively perceived may be more negative in rating the LMX. Altogether, combining the hypotheses that delineate a direct link between the leader's and follower's perception of each other's behaviours and LMX, we propose that the follower's perception of leader's behaviours mediates the link between the leader's perception of follower's behaviour and LMX. Overall, we anticipate that the follower's perception of the leader's behaviours may be a potential contributing explanation to the link between the leader's perception of followers and his/her LMX rating. Therefore:

Hypothesis 3: Given exchange theory and a dyadic relationship, a follower's perception of his/her leader's behaviours mediates the link between the leader's perceptions of his/her follower's (member's) behaviours and the leader's evaluation of LMX quality.

Leaders' emotional reappraisal as a moderator of the link between follower's perception of the leader's behaviours and leaders' rating of LMX quality

We propose that the leadership/followership process is highly connected with emotions (Humphrey, Reference Humphrey2002) and that the leadership/followership process is intrinsically emotional, where leaders display emotions and attempt to evoke emotions in their followers (Gardner, Fischer, & Hunt, Reference Gardner, Fischer and Hunt2009) and vice versa. Especially, an LMX relationship is strongly charged with emotions as both leaders and followers experience positive and negative moods, emotions and emotion-laden judgements (Glasø & Einarsen, Reference Glasø and Einarsen2006) in the relationship. In this regard, an empirical study by Johnson (Reference Johnson2008) demonstrates that individuals in an LMX relationship perceive others in an affect-congruent manner such that people experiencing positive affect perceive others positively while people experiencing negative affect perceive others negatively.

Nevertheless, we are aware that few empirical studies have investigated the link between a leader's emotional behaviour and work outcomes (e.g., leaders rating of LMX quality) at the individual level (see Kluemper, DeGroot, & Choi, Reference Kluemper, DeGroot and Choi2013; Sadri, Weber, & Gentry, Reference Sadri, Weber and Gentry2011), Consequently, we argue that the impact of the follower's perception of the leader in the dyadic relationship and subsequent LMX quality is not void of emotions. For example, liking is an integral part of LMX (Dienesch & Liden, Reference Dienesch and Liden1986) while Liden, Wayne, and Stilwell (Reference Liden, Wayne and Stilwell1993) also report that early liking is more influential in the perception of performance and has the potential to influence the leader's view of an LMX relationship. More recent findings from a meta-analytic study suggest that liking is a critical and unique construct that enables the development of LMX and should continue to be part of the research that investigates dyadic relational quality (Dulebohn, Wu, & Liao, Reference Dulebohn, Wu and Liao2017). In this regard, employees' positive and negative emotions (e.g., from liking/not linking) fully account for the connection between perceived supervisor support and cynicism, while positive affect or the experience of positive emotions is an important aspect of leadership (Frost, Reference Frost2003). Similarly, Clarke and Mahadi (Reference Clarke and Mahadi2017) found that leader emotional intelligence had both direct and indirect effects on follower job performance.

As previously established in H2, the positive follower's perception of the leader's behaviours may evoke positive explicit emotions in the leader, while a negative follower's evaluation of the leader behaviours may trigger negative emotions in the leader. However, these positive and negative emotions are subject to reappraisal/regulation (Gross & John, Reference Gross and John2003). Gross (Reference Gross1998) defines emotion regulation as ‘a process by which individuals influence which emotions they have, when they have them, and how they experience and express these emotions’ (p. 275). Gross' definition is based on the premise that individuals tend to exert considerable control over which emotions they have and how they choose to express them (Gross & John, Reference Gross and John2003).

Emotion regulation is an integral part of any activity involving emotions. Indeed, Fisk and Friesen (Reference Fisk and Friesen2012) show that emotions influence behaviours in both positive and negative ways. In this regard, the leader's surface acting has an indirect negative relationship with follower task performance through LMX (Moin, Wei, Weng, & Ahmad Bodla, Reference Moin, Wei, Weng and Ahmad Bodla2021). Moreover, leaders manage their own emotions as well as influence the emotional states of others (Humphrey, Pollack, & Hawver, Reference Humphrey, Pollack and Hawver2008). Empirical research further demonstrates that managers regulate their feelings as frequently as those who work in traditional emotionally tedious jobs (see Fisk & Friesen, Reference Fisk and Friesen2012). The ability to manage your own and others' emotions is a prerequisite for effective leadership (Côté, Lopes, Salovey, & Miners, Reference Côté, Lopes, Salovey and Miners2010). Yet, the ‘literature on emotion regulation for leadership research is less understood’ (Fisk & Friesen, Reference Fisk and Friesen2012: 2). We reason that at the team level (i.e., beyond the dyadic level); leaders who experience emotions but with high levels of ability to regulate their emotions should also be able to manage their emotions for effective outcomes. Therefore, for the purpose of this research, we focus on one basic emotion regulation strategy: cognitive reappraisal (i.e., what individuals do to alter his/her emotions before a response). While Gross and John (Reference Gross and John2003) argue that both cognitive reappraisal and suppression emotional regulation strategies are the most commonly used in everyday life to achieve social goals and maintain good quality relationships with an individual's significant other, we focus on cognitive appraisal (rather than suppression) because we reason that suppression is concerned with what individuals do to inhibit the outward signs of their inner feelings (Gross, Reference Gross2002) and that this may remove the opportunity to learn from the emotions experienced in LMX interactions.

Broadly, individuals who engage in emotional reappraisal experience greater positive emotions and have better interpersonal relationships (Gross, Reference Gross2002). Also, re-appraisal of positive emotions is associated with an increase in positive affect, self-esteem and psychological adjustment (Nezlek & Kuppens, Reference Nezlek and Kuppens2008). For example, given re-appraisal, the leader who has just promoted a follower may also experience an increased positive emotion because he/she is a part of the follower's career success (depicted by the promotion) and therefore perceive increased LMX quality. Thus, we argue that following reappraisal, positive emotions are more likely to assist in the leaders' perception of high-quality LMX.

The consequences of regulating negative emotions are not that straight forward (Feinberg, Ford, & Flynn, Reference Feinberg, Ford and Flynn2020; Glasø & Einarsen, Reference Glasø and Einarsen2008; Gross, Reference Gross2002; Nezlek & Kuppens, Reference Nezlek and Kuppens2008). Gross (Reference Gross2001) suggests that generally, reappraisal in the emotion-generative process occurs initially to cognitively diffuse a potentially emotion-eliciting situation. Reappraisal should decrease experiential, behavioural and physiological responses of a given emotion. Ayoko and Callan (Reference Ayoko and Callan2010) reported that leaders with high levels of emotional management were strongly related to improved levels of task performance. Given the above, we argue that in an LMX context and at the team level, leaders who reappraise their negative affect should also be able to diffuse the consequences of such negative emotion. This, in turn, should improve their perceptions and rating of LMX quality. Altogether, the effective regulation of emotions (e.g., cognitive reappraisal) may facilitate a supportive context which might act as a buffer in mitigating the negative effects of emotions (Jordan & Troth, Reference Jordan and Troth2004) while promoting the influence of positive emotions in an LMX relationship. Thus:

Hypothesis 4: A leader's emotional reappraisal moderates the association between the follower's assessment of his/her leader's behaviours and the leader's LMX quality such that the relationship is stronger when the leader's emotional reappraisal is low compared with when the leader's emotional reappraisal is high.

Method

Sample and procedure

The military was chosen as a research site for its rich context for the study of leader–follower interactions and dynamics. In the military context, leaders often need to work closely with followers to complete collective goals (Gallus, Walsh, van Driel, Gouge, & Antolic, Reference Gallus, Walsh, Van Driel, Gouge and Antolic2013) in a potentially high-risk context, requiring intensive team interaction, coordination and interdependency. This makes their performance highly visible and influential to each other. Moreover, leaders often act as attachment figures for their followers (Mayseless, Reference Mayseless2010), playing a key role in shaping followers' interpretation of the work environment. The close and attached relationship also makes the appraisal of each other's performance critical to each party. We collected data from a Military Training Centre in the Asia Pacific region. Leaders and followers received written communication from the research team that solicited their voluntary participation and ensured individual responses in the survey will be kept confidential. After written consent was obtained from all participants, two separate sets of surveys were mailed to the leaders and followers. Each leader completed a survey for each follower in his/her dyadic relationships. Similarly, each follower in a dyad was asked to complete the followers' survey in their work time without the presence of their leaders. Each questionnaire was coded with a researcher assigned four-digit identification number to match followers' responses with their leaders. To ensure confidentiality, completed questionnaires by leaders and followers were returned individually in sealed envelopes directly to the research team. No personally identifying information was collected.

A total of 315 male soldiers in 27 teams and their leaders (n = 27) agreed to participate, with a 98.7% response rate. Our response rate was high because one member of the research team was a mid-rank officer in the participating organization and had obtained permission from senior officers to collect data from their unit for this project. This means that participants were allowed to complete the surveys during work time increasing response rate. Team size ranged from 3 to 15 members (average team size = 12). Among 315 followers, most participants were in the age group of 16–25 (99.7%). Most of them completed postsecondary or diploma studies (95.6%). Most of them have been working with their current leaders for 1–6 months (92.1%). Among the 27 leaders, most participants were also in the age group of 16–25 (92.6%). Many of them completed diploma studies (81.5%).

As for the common method bias issue, predictor and criterion variables were collected from different sources as a procedural remedy in our study to overcome concerns for common method bias (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). In our study, the predictor and the criterion of H1 were rated by leaders and followers respectively. Similarly, the predictor and the criterion of H2 were rated by followers and leaders respectively. According to Podsakoff, MacKenzie, and Podsakoff (Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Podsakoff2012: 548), this procedure can ‘diminish or eliminate the effects of consistency motifs, idiosyncratic implicit theories, social desirability tendencies, dispositional mood states, and tendencies on the part of the rater to acquiesce or respond in a lenient, moderate, or extreme manner because they make it impossible for the mindset of a common rater to bias the predictor-criterion relationship.’

Measures: leaders' perception of followers' behaviours

In the present study, we assessed behaviours at the dyadic level. We collected data on leaders and followers' perceptions of their dyadic partners' behaviours using Huang, Wright, Chiu, and Wang (Reference Huang, Wright, Chiu and Wang2008)'s scale. To measure a leader's perception of the follower's behaviours, we employed Huang et al. (Reference Huang, Wright, Chiu and Wang2008)'s 16-item scale to measure the followers' behaviours related to being a team player, reliability, self-directness and commitment to work on a scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. Examples of items include ‘My member communicates well with peers; my member can complete assignments effectively’. Wordings were adapted to suit the context of this study. Reported Cronbach's α was .93.

Followers' perception of leaders' behaviours

We also adapted Huang et al. (Reference Huang, Wright, Chiu and Wang2008)'s 14-item scale to measure followers' perception of leaders' behaviours. The scale has four subscales including mutual understanding, learning and development, friendly attitudes and ability to influence, rated on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Examples of items include ‘I know what my leader is thinking; my leader will discuss things with me even when we have disagreements’. ‘My leader is emotional at work’ was removed given the inappropriateness in military contexts. Reported Cronbach's α was .86.

Leaders' emotional reappraisal

Leaders responded to the four cognitive reappraisal items extracted from the emotion regulation questionnaire (ERQ) developed by Gross and John (Reference Gross and John2003) to measure their emotion regulation strategy. Examples of items include ‘when I want to feel less negative emotions, I change the way I'm thinking about the situation’ and ‘when I want to feel less negative emotions (such as sadness or anger), I change what I am thinking about’. The Cronbach's α reported was .85. Responses were made on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree).

Quality of leader–member exchange

Leaders assessed the quality of their LMX using the 7-point LMX-7 scale developed by Graen and Uhl-Bien (Reference Graen and Uhl-Bien1995). One item that was excluded from the LMX-7 scale was ‘I would use my powers to help my members to solve problems in his or her work’ given the inappropriateness in military contexts. Examples of items on the leader's survey include ‘I have an effective relationship with my follower’ and ‘I understand my member's job problems and needs’. The reported Cronbach's α was .78.

Statistical analyses

The study had a two-level design: leader–member dyadic relationships were embedded within the group which is supervised by a leader. Therefore, leader–member perceptions of each other's behaviours and LXM quality were conceptualized at the dyadic level (Level 1) and leader emotional reappraisal was conceptualized at the leader/group level (Level 2). To take account of the nested structure, the data were analysed via multi-level modelling with bootstrapping using Mplus 7.2 software (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén2007). In view of our interest in cross-level moderation, the Level 1 predictors and control variables were centred on the group mean and the Level 2 predictors and control variables were centred on the grand mean (see Enders & Tofighi, Reference Enders and Tofighi2007; Hofmann & Gavin, Reference Hofmann and Gavin1998).

We controlled the duration of the leader–member relationship at Level 1. At Level 2, the leader's age was controlled on Level 2 intercept of leader's interpersonal cognitive assessment. Neither age nor duration of leader–member relationship added any significance to our results, and therefore they were not included in the final model testing.

Results

Hypothesis testing

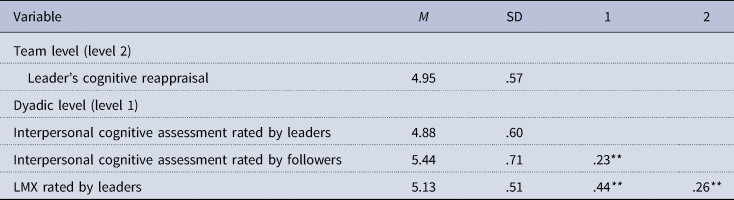

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, reliabilities and correlations of variables used in the current study. An inspection of the correlations revealed that leader's assessment of follower's behaviours was positively correlated with the follower's assessment of leader's behaviours (r = .23, p < .01). A follower's assessment of leader's behaviours was positively related to LMX quality rated by leader (r = .26, p < .01). These bivariate results provided preliminary support for the hypothesized relationships.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics, internal consistency reliabilities, and correlations at level 1 (dyadic-level) and level 2 (team-level)

** p < .01.

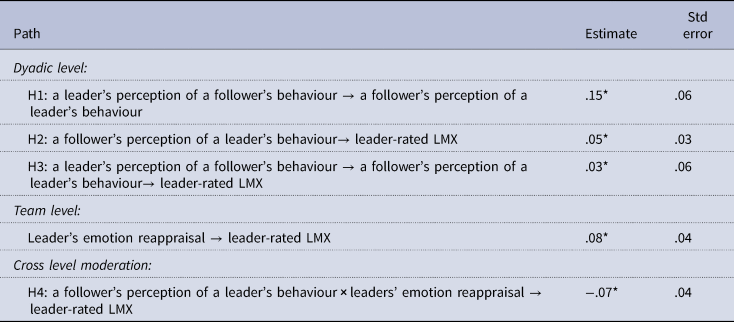

Table 2 presents standardized coefficient estimates for model testing. Results showed significant positive relationship (β = .15, p < .05) suggesting that follower's interpersonal assessment of leader's behaviour was high when leader's interpersonal assessment of follower's behaviour was high, confirming H1. Follower's interpersonal assessment of leader's behaviour was also positively related to LXM rated by leaders (β = .05, p < .05), supporting H2.

Table 2. Final results of model testing in the prediction of LXM rated by leaders

*p < .05.

The mediation hypothesis (H3) was tested using bootstrapping procedures for the mediation test outlined by Selig and Preacher (Reference Selig and Preacher2008). We found that the indirect effect for leaders' interpersonal assessment of follower's behaviour → follower's interpersonal assessment of leader's behaviour → LXM rated by leaders was .03, significantly different from zero with a 90% CI of [.01–.06]. Therefore, the mediating effect of follower's interpersonal assessment of leader's behaviour was significant, providing support for H3.

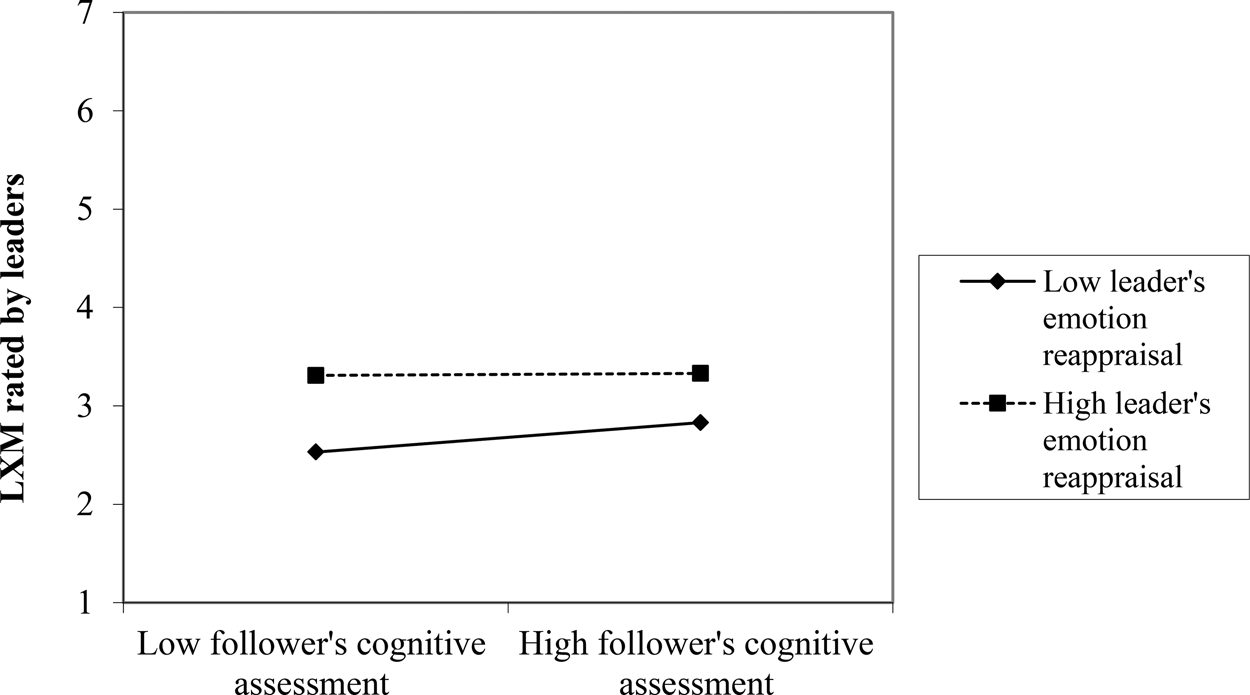

To test the hypothesized cross-level moderation effect, we tested the effect of leader's emotional reappraisal on the random slope for follower's interpersonal assessment predicting LXM rated by leaders. Leader's emotional reappraisal was related to the random slope between follower's interpersonal interactional assessment and LXM rated by leaders (r = −.07, p < .05). Following Cohen, Cohen, West, and Aiken's (Reference Cohen, Cohen, West and Aiken2003) recommendations, the interaction graph was plotted at conditional values of leader's emotional reappraisal (1 standard deviation above and below the mean). As shown in Figure 2, the relationship between follower's interpersonal assessment and LXM rated by leaders was stronger when leader's emotional reappraisal was low (vs. high), supporting H4.

Figure 2. Leader's emotion reappraisal moderated the effects of follower's interpersonal cognitive assessment and LXM rated by leaders.

Discussion

The current research is an examination of leader's and follower's perception of each other's behaviours, leader's emotional reappraisal and leader's rating of LMX quality. Numerous empirical studies (e.g., Dienesch & Liden, Reference Dienesch and Liden1986) have examined a variety of antecedents to LMX relationships. Although outcomes of previous studies suggest that leaders play a prominent part in shaping the LMX quality, we depart from this dominant view and argue that followers are able to influence the LMX processes as well (Dienesch & Liden, Reference Dienesch and Liden1986). Also, researchers (e.g., Fisk & Friesen, Reference Fisk and Friesen2012) have continually called for more research on emotion regulation. Thus, drawing on dyadic, emotions and LMX literature, we proposed a cross-level model to examine the influence of leader's assessment on follower's behaviours (and vice versa) and assessment of LMX quality. We answer this call and extend research in this area by examining the moderating role of leader's emotional regulation (reappraisal) in the link between the follower's assessment of leader's behaviours and leader's evaluation of the LMX quality. We found that a leader's perception of his/her follower's behaviours was related to the follower's perception of his/her leader's behaviours (H1). While we are aware of the existence of differentiated perceptions of LMX between the leader and the follower (Goswami, Park, & Beehr, Reference Goswami, Park and Beehr2019) and that the LMX differentiation process leads to patterns of LMX relationships (Martin, Thomas, Legood & Dello Russo, Reference Martin, Thomas, Legood and Dello Russo2018), our study found that the leader's perceptions of the follower's behaviour are antecedent to the follower's perception of the leader's behaviour. Our results depart from the traditional alignment or nonalignment of leader and follower assessment of their LMX (Gooty et al., Reference Gooty, Thomas, Yammarino, Kim and Medaugh2019) implying that it is the leader's perception of the follower's behaviour that, in part, is a key driver of the follower's perception of the leader's behaviour in a dyadic relationship.

With respect to the link between followers' perception of leaders' behaviours and leaders' rating of LMX quality (H2), our results revealed that followers' perceptions of the leader's behaviours relate to the leader's rating of the LMX quality. Existing literature suggests that through sense making or implicit leadership theory (Junker & Van Dick, Reference Junker and Van Dick2014), the leader assesses his/her LMX relationship with his/her follower (Van Gils, Van Quaquebeke, & Van Knippenberg, Reference Van Gils, Van Quaquebeke and Van Knippenberg2010; Weick, Reference Weick1993) and this impacts the leaders rating of their LMX relationship (see Dulebohn et al., Reference Dulebohn, Bommer, Liden, Brouer and Ferris2012; Sin, Nahrgang, & Morgeson, Reference Sin, Nahrgang and Morgeson2009). Our results linked follower's behaviours to leader's rating of LMX quality. Given the above results, three important questions can be raised: (a) how these results assist us further in isolating the follower's role in how the leader perceives the LMX quality, (b) how these results contribute to our understanding of the follower's role in triggering leader's emotions, and (c) how these findings increase our understanding of the consequences of leaders' emotion regulation (i.e., reappraisal) in the context of LMX relationship. Baldwin et al. (Baldwin & Baccus, Reference Baldwin, Baccus, Spencer, Ferris, Zanna and Olson2003) posit that LMX representations function as ‘if-then’ scripts for workers so that they can anticipate relationships based on their dyadic experiences and thus should be able to predict the quality of the leader's experience of LMX (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Wright, Chiu and Wang2008).

With regards to the followers' perception of leaders' behaviours and leaders' perception of the LMX relationship, our results demonstrate that, indeed, followers are not passive recipients of leader's trait and skills (Oc & Bashshur, Reference Oc and Bashshur2013) but have a significant role to play in how leaders perceive LMX relationship, style and effectiveness. By employing sense making and exchange theories we extend the LMX literature by demonstrating that followers' sense making and interpretations of their present LMX relationship may have a potentially powerful impact on their leaders (see also Goswami, Park, & Beehr, Reference Goswami, Park and Beehr2019; Lord & Maher, Reference Lord and Maher1991). Our findings demonstrate that the extent to which a leaders' role meets the followers' relational expectations, and his/her consequent perception of the leader's behaviours may also influence the leader's rating of the LMX quality. In this respect, we extend research in sense making, perceptions, behavioural and LMX. Altogether, our findings further provide strong evidence that followers play a crucial role in the leadership process and experience.

Additionally, we found that the follower's perception of his/her leader's behaviours mediates the link between the leader's perceptions of his/her follower's behaviours and the leader's evaluation of LMX quality (H3). Several studies have investigated the underlying mechanism for an LMX relationship. For example, Xu et al. (Reference Xu, Loi, Cai and Liden2019) found that leader perceived resources (i.e., efforts and actions of the focal follower that make leaders' work more effective) are an underlying mechanism for the LMX relationship. Similarly, Lee, Gerbasi, Schwarz, and Newman (Reference Lee, Gerbasi, Schwarz and Newman2019) found that LMX social comparison was related to followers' organizational commitment and job performance though followers felt obligation towards the leader. Yang, Huang, and Zhou (Reference Yang, Huang and Zhou2021) also explored the need for satisfaction as a mediator of the link between follower LMX and turnover intention. This study departs from the rest by investigating the follower's perception of their leader's behaviour as the underlying mechanism for the leaders rating of the LMX quality. Altogether, our findings add to the possible underlying mechanism through which LMX is influenced.

Our results that leaders' emotional reappraisal moderates the link between followers' assessment of his/her leader's behaviours and leaders rating of LMX (H4) contribute to elucidate the follower's triggering role in leaders' emotions. Studies have explored the role of emotions in the LMX process (see Glasø & Einarsen, Reference Glasø and Einarsen2006; Gooty et al., Reference Gooty, Thomas, Yammarino, Kim and Medaugh2019; Little, Gooty, & Williams, Reference Little, Gooty and Williams2016; Silard & Dasborough, Reference Silard and Dasborough2021). For example, Glasø and Einarsen (Reference Glasø and Einarsen2006) found that that leader–subordinate relationships are strongly charged by positive and negative moods, emotions and emotion-laden judgements. Additionally, Moin et al. (Reference Moin, Wei, Weng and Ahmad Bodla2021) found that leader emotion regulation strategies played a key role in improving or hurting LMX. Our result is in consonance with the above result. Specifically, our results resonate with Glasø and Einarsen (Reference Glasø and Einarsen2006)'s findings that leaders experience emotions (positive and negative) in a leader–member relationship that may need appraisal or regulation. Beyond the above findings, our results demonstrate that the follower's perception of their leader's behaviour in the presence of leader emotional reappraisal may be a critical precursor in the leader's own rating of the quality of LMX. Overall, the leader's experienced emotions and appraisal in the LMX context may not be immune from the way the followers perceive his/her relationship with the leader. Based on our findings, we suggest that leaders (like followers) need to satisfy the followers' expectations to derive some LMX quality experience. Altogether, we extend the literature on the underlying sources of leaders' emotions in the workplace.

Theoretical implications and contributions

Our findings pave the way for future studies to further explicate the link between dyadic behaviours, emotional reappraisal and LMX in many ways. First, we adopted sense making and sense giving perspectives and LMX theory to empirically demonstrate the role of leader and follower perceptions of each other's behaviours and leaders' emotional reappraisal of the LMX experience in the workplace. Our findings suggest that leaders' perception of the followers' behaviours and followers' perception of their leaders' behaviours in the presence of leader emotional reappraisal are associated with the leader's own rating of the quality of LMX relationship. This shows that the leaders' behaviours have a significant direct influence on the quality of LMX as rated by the leader extending possible antecedents to the LMX quality.

Second, our findings shed new lights on the underlying processes by which followers might impact their leaders in the process of LMX development. For example, our results show that followers' perception of the leaders' behaviours has a potential to influence leaders' own rating of LMX. The follower's perception of the leader's behaviours mediated the relationship between leader's behaviours and leader's rating of the LMX quality at the dyadic level.

Third, we extend the literature on emotional reappraisal/regulation. Liden (Reference Liden2012) argues that instead of developing leadership theories and measures unique to specific countries, such as China, the search light should be on the identification of moderators that explain relationships between leadership and both its antecedents and outcomes. The current research examined leaders' emotional reappraisal as a moderating variable between followers' perception of leader's behaviours and LMX as rated by leaders. Outcomes of the present study reinforce the notion that both leadership and LMX relationships have underlying emotional interactions thereby extending literature on emotions and leadership. Our findings suggest that emotional reappraisal may be an integral part of the LMX relationship. For example, we now know that emotional reappraisal has the potential to moderate follower's perceptions of his/her leader's behaviours for increased LMX quality. Altogether, we have demonstrated that the follower has a significant role in the LMX relationship, especially in eliciting the leader's emotional regulation (reappraisal).

Managerial implications and contributions

Our current research presents two managerial implications. First, an understanding that a follower's assessment of the leader's behaviours is a possible antecedent to the development of high-quality LMX relationships, suggests that managers need to think seriously about how their followers perceive them to achieve better LMX outcomes. For example, leaders may wish to continually seek feedback from their followers in an LMX relationship. The constant evaluation and feedback from the follower in this process should ensure that leaders have a clear understanding of the relational expectations of followers. This, in turn, should reduce role conflict and ambiguity (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Wright, Chiu and Wang2008) while improving LMX consensus that is important for job performance, organizational commitment and job satisfaction (Cogliser, Schriesheim, Scandura, & Gardner, Reference Cogliser, Schriesheim, Scandura and Gardner2009). Both role conflict and role ambiguity can be minimized by managing role expectations of both leaders and followers in their dyadic relationship and effective feedback-seeking behaviours from a supervisor and follower (see Ayoko, Konrad, & Boyle, Reference Ayoko, Konrad and Boyle2012; Mohr & Puck, Reference Mohr and Puck2007; Srikanth & Jomon, Reference Srikanth and Jomon2013). The reduction of role ambiguity and role conflict should, in turn, minimize the misalignment in the leader's perception of follower's behaviours in the LMX relationship and vice versa that may impact the quality rating of LMX from the leader.

Also, while we are aware that the concept of LMX cuts across many countries and cultures (Liden, Reference Liden2012), cultural variables have been found to moderate the relationship between antecedents and LMX, and between LMX and outcomes (Liden, Reference Liden2012). In this regard, Dulebohn et al. (Reference Dulebohn, Bommer, Liden, Brouer and Ferris2012) showed that although the correlation between leader trust and LMX was positive in all cases, this was especially higher in contexts with higher levels than low levels of individualism. Additionally, Jung and Avolio (Reference Jung and Avolio1999) argued that ‘there is typically a high level of value congruence between followers and leaders owing to extensive socialization processes in collectivist culture’ (p. 209). Our findings typically demonstrate how leaders' mental processes influence followers' mental processes in their socialization process and consequently influence the effectiveness of their socialization (manifested as LMX quality) in the Asian cultural context where our data were collected. More research is needed to explicate the cultural factor in leaders' and followers' perception of each other's behaviours and the way this may be related to leaders' rating of LMX quality.

Second, the ability to effectively regulate emotions (i.e., reappraisal) may indeed be a key determinant of effective leadership (Kerr, Garvin, Heaton, & Boyle, Reference Kerr, Garvin, Heaton and Boyle2006). Our findings show that leaders' reappraisal of emotions may be a crucial player in their perception of LMX quality. From a managerial and Human Resource Management (HR) perspective, it is imperative that organizations take a firm step to train their leaders to perceive, understand and manage their emotions effectively. For example, a manager's ability to manage his/her emotions could be included in the recruitment and selection process (Kerr et al., Reference Kerr, Garvin, Heaton and Boyle2006) as well as the orientation training for managerial personnel (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Wright, Chiu and Wang2008). Training in emotion management may assist in facilitating the development of high-quality LMX relationships for both leaders and followers that may reduce interpersonal conflicts and misunderstanding (Ayoko, Callan, & Hartel, Reference Ayoko, Callan and Hartel2008) to achieve positive organizational outcomes.

Limitations and future research

Like all research, this study has four apparent limitations. First, the current study is cross-sectional, and the lack of a longitudinal design may obscure the direction of the links and causality in the LMX relationship. While we acknowledge the limitation of cross-sectional studies, the results presented in the current research should be interpreted and generalized with caution.

Second, further studies should examine the emergence process (Kozlowski & Chao, Reference Kozlowski and Chao2012) of differentiated assessment of LMX relationship using a longitudinal approach. For example, a longitudinal study will allow researchers to observe and examine how follower's perception of the leader's behaviours and the leader's emotions may impact the quality of LMX over time. Moreover, the effect of the follower's perception of the leader's behaviours on leader's emotional reappraisal and evaluation of LMX quality assumes that followers and leaders often transmit their expectations in LMX with each other (see Huang et al., Reference Huang, Wright, Chiu and Wang2008). More research (especially qualitative) is needed to elucidate the processes by which leaders and followers communicate their relational expectations to each other in the process of LMX development.

Third, we have focused on the follower's perceptions as having an influence on leader's assessment of LMX quality. Future research should explore the possibility of the congruence or disparity between leader and follower assessment of each other's behaviours as a possible predictor of LMX quality for both leaders and followers.

Fourth, the present research was conducted in a military setting and with participants from one single gender. We expect that our findings are likely to generalize to other settings where follower and leaders perform complex, interdependent and often unpredictable tasks (Lim & Klein, Reference Lim and Klein2006). Nevertheless, additional research is recommended to test the generalizability of the results to other organizational contexts and with mixed genders.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we believe that the current study contributes to literature by testing a cross-level model of the link between the leader's perception of follower's behaviours, follower's interpersonal perception of leader's behaviours, leaders' emotional reappraisal and leader's perception of LMX quality. Overall, our model is supported by findings from this research which have expanded our knowledge about the ways in which a follower's perception of his/her leader may indirectly influence the leaders' emotional reappraisal and perceptions of their LMX quality. Similarly, the current research has empirically shown that leader's emotional regulation strategy moderates the link between the follower's assessment of the follower and leaders' rating of LMX. These findings are expected to improve organizational leaders' ability to experience high-quality LMX relationship and positive organizational outcomes.

Oluremi B. Ayoko (PhD, University of Queensland, Australia) is an Associate Professor in the UQ Business School, University of Queensland. Her research interests include conflict management, emotions, leadership, diversity, teamwork and employee physical and virtual work environment. She has published in reputable journals such as Journal of Organizational of Behavior (JOB), Organization Studies, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, Journal of Business Ethics and Journal of Business Research. She has also written many book chapters and co-edited the Handbook of Conflict Management Research and Organizational Behaviour and the Physical Environment.

Pao P. Tan was a postgraduate student at the University of Queensland Business School. His research interests include leadership, LMX and emotional regulation.

Yiqiong Li (PhD) is a senior Lecturer in Management at the University of Queensland Business School. Yiqiong's research is focused on human resource management practices and employee health and safety, and their intersection.