INTRODUCTION

Organizations in the hectic and complex environment of today need to necessarily adopt an adaptive and responsive approach and therefore encourage creative behavior among employees. Organizations today exist in an environment inundated with changing and ever-increasing consumer demands, along with escalating performance standards for employees as a result of globalization and technology changes (Heunks, Reference Heunks1998; Shalley, Zhou, & Oldham, Reference Shalley, Zhou and Oldham2004; Belleflamme & Peitz, Reference Belleflamme and Peitz2015). Hence, organizational leaders are under a great deal of pressure to find ways to increase creativity in their organization due to increasing globalization, competition, and pace of technological change. For organizations as these, creativity is thus regarded as a core competence. Needless to say, today, creativity is no longer regarded as an innate quality that only some individuals possess (Amabile, Conti, Coon, Lazenby, & Herron, Reference Amabile, Conti, Coon, Lazenby and Herron1996), but is increasingly being considered as a competence to be further improved and/or developed in all employees through adequate experience and training (Scott, Levitz, & Mumford, Reference Scott, Levitz and Mumford2004). Therefore, at the current time, researchers and practitioners equate organizational survival and success with employees’ creativity (Hirst, Van Knippenberg, & Zhou, Reference Hirst, Van Knippenberg and Zhou2009; Williams & McGuire, Reference Williams and McGuire2010; Xia & Li-Ping Tang, Reference Xia and Li-Ping Tang2011). Consequently, organizations are focusing on bringing creativity among employees and moreover, they are specially paying attention in identifying ways to promote creativity (Hon, Hon, Lui, & Lui, Reference Hon, Hon, Lui and Lui2016).

Creativity, in essence, brings something new into the organization. It results in the attainment of a certain degree of intellectual knowledge and a level of emotional maturity aided by a freedom of expression and the opportunity to use all resources (Townsend, Reference Townsend2000). It is worthwhile to differentiate between the concepts of creativity and innovation. While creativity is defined as ‘the production of novel and useful ideas in any domain,’ innovation is ‘the successful implementation of creative ideas within an organization’ (Amabile et al., Reference Amabile, Conti, Coon, Lazenby and Herron1996: 1155). Since creativity involves generating new and novel ideas at the workplace (Amabile, Reference Amabile1983, 1996), which indicates that employees are encouraged to disagree with the leader and raise their voices to improve the work process (Chughtai, Reference Chughtai2016). Therefore, creativity is enhanced in an organizational culture which nurtures and encourages a creative environment (Chua, Roth, & Lemoine, Reference Chua, Roth and Lemoine2015). Leadership as a important part of organizational culture, play an important role with supportive behavior in creating and enhancing creativity (Amabile, Schatzel, Moneta, & Kramer, Reference Hahn, Lee and Jo2004).

Research scholars have paid significant attention to the supportive role of leadership in promoting employees’ creativity (Javed, Bashir, Rawwas, & Arjoon, Reference Javed, Khan, Bashir and Arjoon2017). Numerous studies have found that supportive behavior of leadership and the leader’s ethical behavior to have a major positive impact on employees’ creativity (Zhu, May, & Avolio, Reference Zhu, May and Avolio2004; Brown, Treviño, & Harrison, Reference Brown, Treviño and Harrison2005; Gu, Tang, & Jiang, Reference Gu, Tang and Jiang2015). While employees’ creativity decreases with leadership controlling behavior (Tierney & Farmer, Reference Tierney and Farmer2002, Reference Tierney and Farmer2004; Jung, Chow, & Wu, Reference Jung, Chow and Wu2003; Wang & Zhu, Reference Wang and Zhu2011; McMahon & Ford, Reference McMahon and Ford2013). In every organization, employees are bound to follow certain standardized norms (Javed, Naqvi, Khan, Arjoon, & Tayyeb, Reference Javed, Naqvi, Khan, Arjoon and Tayyeb2017). However, creativity is a special case where employees go beyond the standardized norms and challenge the status quo, many a times by disagreeing with the leader (Baucus, Norton, Baucus, & Human, Reference Baucus, Norton, Baucus and Human2008; Javed, Khan, Bashir, & Arjoon, Reference Javed, Khan, Bashir and Arjoon2017). Moreover, generating new ideas does not guarantee success and even creativity can result in ethical dilemmas (Yidong & Xinxin, Reference Yidong and Xinxin2013). Therefore, leaders need to be ethical in their approach for their employees to exhibit creativity (Ma, Cheng, Ribbens, & Zhou, Reference Ma, Cheng, Ribbens and Zhou2013). Ethical leaders with open communication channels promote a supportive environment, which promotes employee creativity (Chughtai, Reference Chughtai2016).

Moreover, there are various mediated mechanisms that mediates in the relationship between ethical leadership and creativity. Particularly, Javed et al. (Reference Javed, Khan, Bashir and Arjoon2016) called future researchers to check the role of mediated mechanism of trust in leadership in the relationship between ethical leadership and creativity. In order to respond to this call, in the current study, we used trust in the leadership as a mediated mechanism between ethical leadership and employees’ creativity. We found limited evidence to demonstrate how trust in a leader might play a mediating role between ethical leadership and employees’ creativity. Trust indicates the willingness to have dependence on other people (Mayer, Davis, & Schoorman, Reference Mayer, Davis and Schoorman1995). Trust also shows the expectation that other people will behave positively if one cooperates with them (Cook & Wall, Reference Cook and Wall1980; Lane & Bachmann, Reference Lane and Bachmann1998; Rousseau, Sitkin, Burt, & Camerer, Reference Rousseau, Sitkin, Burt and Camerer1998; van den Akker, Heres, Lasthuizen, & Six, Reference van den Akker, Heres, Lasthuizen and Six2009). Trust plays an important role in the relationship between leaders and their employees and effective trust show positive consequence via cooperation, information sharing and by increasing openness (Mayer, Davis, & Schoorman, Reference Mayer, Davis and Schoorman1995; Lane & Bachmann, Reference Lane and Bachmann1998; Dirks & Ferrin, Reference Dirks and Ferrin2002; Den Hartog, 2003; Deutsch, Reference Deutsch1973). Moreover, when employees show trust in their leader, the former exhibit increased willingness to take on the risk of creativity (Zhang & Zhou, Reference Zhang and Zhou2014).

While exhibiting a particular behavior, employees constantly monitor the work environment to decide whether they should repose trust in their leader (Carnevale, Reference Carnevale1988; Dirks & Ferrin, Reference Dirks and Ferrin2002; Newman, Kiazad, Miao, & Cooper, Reference Newman, Kiazad, Miao and Cooper2014). Ethical leadership has been found to significantly influence employees’ trust in their leader (van den Akker et al., Reference van den Akker, Heres, Lasthuizen and Six2009; Engelbrecht, Heine, & Mahembe, Reference Engelbrecht, Heine and Mahembe2014). Leaders with strong ethical values generally honor their word and commitments made and communicate the same to their employees, which further reinforces their employees’ trust in them (Avolio, Gardner, Walumbwa, Luthans, & May, Reference Avolio, Gardner, Walumbwa, Luthans and May2004; Schoorman, Mayer, & Davis Reference Schoorman, Mayer and Davis2007; Dadhich & Bhal, Reference Dadhich and Bhal2008). Moreover, researchers found that when employees trust their leader, they exhibit creativity without experiencing a fear of failure (Dietz & Den Hartog, Reference Dietz and Den Hartog2006; Chen, Chang, & Hung Reference Chen, Chang and Hung2008; Bidault & Castello, Reference Bidault and Castello2009, Reference Bidault and Castello2010; Brattström, Löfsten, & Richtnér, Reference Brattström, Löfsten and Richtnér2012). These findings show that trust in a leader mediates the relationship between ethical leadership and employees’ creativity.

Moreover, literature on creativity shows that creativity does not come from all employees (Schilpzand, Herold, & Shalley, Reference Schilpzand, Herold and Shalley2010; Simmons, Reference Simmons2011). This is because; all employees have not a creativity relevant personality. It is evident that employees with a certain creativity relevant personality trait exhibit creativity (Kim, Hon, & Crant, Reference Kim, Hon and Crant2009). Feist (1999) stated that taking the five factor personality dimensions into consideration, the dimension which is very strongly related to creativity is openness to experience. Employees who demonstrate an openness to experience are those who exhibit creative behavior and ‘out of the box’ thinking (Simmons, Reference Simmons2011). Since creativity promotes ‘out of the box’ thinking, employees are thus encouraged to develop new and innovative ideas as opposed to old and traditionally prevailing ideas (Shelley, Zhou, & Oldham, 2004; Schilpzand, Herold, & Shalley, Reference Schilpzand, Herold and Shalley2010). Thus, when employees show trust in their leader then they show more creativity when they are high on openness to experience. This shows the moderation of openness to experience between trust in leader and employees’ creativity. To our knowledge, no study has theoretically and empirically tested the moderation of openness to experience on the relationship between trust in a leader and creativity.

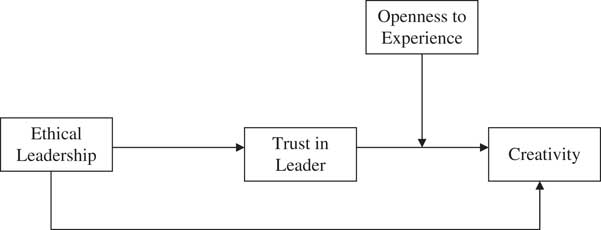

The current study contributes, in several ways, to the theoretical development of creativity. First, this study attempts to find out the effect of ethical leadership on creativity. Second, the current study will test the mediating role of trust in the leader between ethical leadership and creativity. Third, this study will also examine the moderating role of openness to experience between trust in a leader and creativity. The research model is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Hypothesized model

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

Ethical leadership and creativity

Ethical leadership is defined as ‘the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to subordinates through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-making’ (Brown, Treviño, & Harrison, Reference Brown, Treviño and Harrison2005: 120). In other words, this definition highlights three main characteristics of an ethical leader: he or she is the one who (a) practices what he or she preaches, (b) believes in justice, and (c) communicates meaningful information.

Differential association theory may address the first component of the ethical leader’s characteristics (i.e., practicing what he or she preaches). It states that employees learn moral or immoral conduct while working with their colleagues and leaders (Ferrell, Fraedrich, & Ferrell, Reference Ferrell, Fraedrich and Ferrell2013). Research has also found that the influence of ethical values of superiors on subordinates outweighs that of peers (Mayer, Kuenzi, & Greenbaum, Reference Mayer, Kuenzi and Greenbaum2010), because workers have a tendency to go along with their superiors’ moral decisions to exhibit loyalty (Ferrell, Fraedrich, & Ferrell, Reference Ferrell, Fraedrich and Ferrell2013). Social learning theory points out that this ethical influence takes place through a role-modeling process (Bandura, Reference Bandura1977; Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes, & Salvador, Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009). It can be achieved when leaders participate in behaviors that advance the well-being of others and abstain from behaviors that may cause damage to others (Toor & Ofori, Reference Toor and Ofori2009). These leaders may use several strategies to empower their subordinates, enhance their self-efficacy, and modify their values, norms, and attitudes to align with their organization’s and community’s standards.

Organizational justice theory, developed by Greenberg (Reference Greenberg1987) and modified by Colquitt (Reference Colquitt2001), may address the second component of the ethical leader’s characteristics (i.e., believing in justice). It argues that an employee judges the behavior of the leader and reacts accordingly. The judgment and the reaction go through four stages: distributive, procedural, interpersonal, and informational. Employees first evaluate the fairness associated with the distribution of resources that could be tangible, such as pay increase, or intangible, such as recognition, in the distributive stage. If they perceive that such distribution is equitable, then perception of justice prevails. Employees then question the process that lead to the decision to distribute a ‘pay increase’ or ‘recognition’ in the procedural stage. If they feel that the process is consistent, ethical, unbiased, and inclusive of their voices, then their perceptions of justice are enhanced. In the third interpersonal stage, employees judge their leader’s behavior toward them. If the leader treats them with politeness, dignity, and respect, then their satisfaction is furthered. Finally, employees shift to a higher stage of evaluation: the informational stage. They judge the leader’s explanations of his or her decisions. If the leader is truthful, specific, and timely in providing information, such as why a ‘pay increase’ is distributed in a certain way, then employees are content.

As organizational actions and/or decisions of leaders are perceived as just, employees are more likely to participate in cooperative behaviors in which they support the organization beyond the scope of their job description. Research has found that cooperative behaviors are in turn strongly related to opportunities for creativity (Obiora & Okpu, Reference Obiora and Okpu2015).

In conclusion, ethical leaders respect and tolerate employees’ divergent views and values through their advancement of the trust, honesty, consideration, virtuousness, and fairness within their relationships (Northouse, Reference Northouse2016). They shape and affect corporate culture, encourage the autonomy of employees, and value their ideas (Piccolo, Greenbaum, Hartog, & Folger, Reference Piccolo, Greenbaum, Hartog and Folger2010), which boosts employees’ creativity (Iqbal, Bhatti, & Zaheer, Reference Iqbal, Bhatti and Zaheer2013). In fact, several researchers have reported that honest leaders do not avoid uncertainty by allowing their subordinates to take risks, and hence, be more creative (Kouzes & Posner, Reference Kouzes and Posner2003; Benni & Nanus, Reference Benni and Nanus2007; Caldwell & Dixon, Reference Caldwell and Dixon2010; Gu, Tang, & Jiang, Reference Gu, Tang and Jiang2015; Javed et al., Reference Javed, Khan, Bashir and Arjoon2016). Based on the above theories and research findings, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Ethical leadership is positively related to creativity.

Mediating role of trust in leader between ethical leadership and creativity

Trust is ‘the willingness of a party to be vulnerable to the actions of another party’ (Mayer, Davis, & Schoorman, Reference Mayer, Davis and Schoorman1995: 712). Creativity is defined as a process of finding solutions to problems, deficiencies, disparities in knowledge, missing components, and dissonances (Torrance, Reference Torrance1974).

Transactional cost analysis and herding behavior theories may explain the third component of the ethical leader’s traits (i.e., communicating meaningful information). Transactional cost theory states that the economic system in general and organizations in particular require trust to be built on moral foundations and community standards as the basis for successful business operation (Williamson, Reference Williamson2002). However, complexity and lack of transparency mean that information is highly disproportionate; giving managers an edge over subordinates (Global Economic Symposium, 2017). Even if information is accessible, it may come at a high cost. When employees are confronted with a situation of ‘information impactedness’ (a term that was developed by Williamson, Reference Williamson2002) in which information is known to management but cannot be obtained by employees without a cost, employees may feel vulnerable and retreat to a less risky environment. According to herding theory, employees may amalgamate with other employees by adopting a herding behavior in which each individual group member attempts to move as close as possible to the center of the group to reduce the harm to him or her (Rook, Reference Rook2006). At the center, employees act in the same way at the same time as the rest of their group members (Raafat, Chater, & Frith, Reference Raafat, Chater and Frith2009). They are unwilling to take risks, be exposed, or share ideas. This behavior hinders organizational productivity and creativity because when an employee camouflages himself or herself, his or her participation and commitment to the organization deteriorate. As it becomes more costly to obtain information, fewer employees are willing to contribute, and the organization may encounter more damage.

In this situation, the role of ethical leaders becomes very critical. Research has found that ethical leaders overcome communication gaps, which builds trust in employees (Den Hartog, 2003). Because of their trustworthy trait, ethical leaders are willing to be transparent and communicate adequate information, which may diminish organizational dissemination of information discrepancy and boost trust. By empowering employees with information, ethical leaders affirm the value of the contribution of their employees. Employees in turn develop deeper commitments to organizational and departmental objectives by offering input and making decisions that affect the organization’s success and prosperity (Chen & Hou, Reference Chen and Hou2016). This environment encourages employees to share ideas, express creativity, and actively engage in making decisions and improvements (Chen & Hou, Reference Chen and Hou2016).

In line with the above discussion linking trust with ethical behavior, trust may also be defined as one entity’s expectation of ethically justifiable behavior, especially if it grows out of commonly accepted principles and social norms (Hosmer, Reference Hosmer1995). Dirks and Ferrin (Reference Dirks and Ferrin2002) found that the most important antecedents for trust in leaders are leadership style and practices. They also suggested that role-modeling behavior may be responsible for the effects of ethical leadership. Research findings suggest that integrity is especially important in cases of trust building (Lapidot, Kark, & Shamir, Reference Lapidot, Kark and Shamir2007) and have found a strong relationship between trust and ethical leadership (Solomon & Flores, Reference Solomon and Flores2001; Dirks & Ferrin, Reference Dirks and Ferrin2002; Caldwell & Clapham, Reference Caldwell and Clapham2003; Den Hartog, 2003; Mayer & Gavin, Reference Mayer and Gavin2005; Kolp and Rea, Reference Kolp and Rea2006; Lapidot, Kark, & Shamir, Reference Lapidot, Kark and Shamir2007; Caldwell, Hayes, Bernal, & Karri, Reference Caldwell, Hayes, Bernal and Karri2008; De Hoogh & Den Hartog, Reference De Hoogh and Den Hartog2008; Zhu, Reference Zhu2008; Bello, Reference Bello2012). In fact, ethical integrity was reported to be an important aspect of leadership (Craig & Gustafson, Reference Craig and Gustafson1998) and increased levels of trust (Caldwell et al., Reference Caldwell, Hayes, Bernal and Karri2008). Trustworthiness of the leader was in turn perceived as a significant prerequisite for an ethical leader (Treviño & Weaver, Reference Treviño and Weaver2003; Treviño, Weaver, & Reynolds, Reference Treviño, Weaver and Reynolds2006).

According to previous theories and research findings, trust is an important factor that explains (i.e., mediates) the relationship between ethical leaders and creativity. Despite its significance, the literature on the effect of trust on creativity remains inconclusive. On one hand, some studies did not find a direct and positive relationship between trust and creativity (De Clercq, Thongpapanl, & Dimov, Reference De Clercq, Thongpapanl and Dimov2007; Chen, Chang, & Hung, Reference Chen, Chang and Hung2008). On the other hand, several other researchers observed that trust was conducive to inducing creativity and innovation when communication was open and environments were supportive, tolerant, and friendly (Simons & Peterson, Reference Simons and Peterson2000; Martins & Terblanche, Reference Martins and Terblanche2003; Dakhli & De Clercq, Reference Dakhli and De Clercq2004). Generating new ideas includes getting involved in divergent reasoning, producing a variety of possible solutions, communicating with others, revising alternatives, and choosing skillful remedies to new problems (Zhou, Reference Zhou2003). Trust is hence an important trait for ethical leaders to have in order to boost employees’ morale, creativity, cooperation, information sharing, and openness (Dirks & Ferrin, Reference Dirks and Ferrin2002; Den Hartog, 2003; Bidault & Castello, Reference Bidault and Castello2009). Accordingly, we have developed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Trust in leader mediates the relationship between ethical leadership and creativity.

Moderating role of openness to experience between trust in leader and creativity

Epistemology theory may shed light on the relationships among trustful leaders, creativity, and openness to experience. Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that assesses opposing interpretations about the ethicality, spirit, standards, bases, and functions of knowledge (Lahroodi, Reference Lahroodi2007). Employees who adopt epistemic virtues manage to have favorable opinions of moral cognition and eagerly process ethical situations based on their character, reasoning, proficiency, and knowledge. Open-mindedness, curiosity, careful thinking, creativity, and intellectual courage are the foundations of epistemic virtues (see e.g., Kawall, Reference Kawall2002; Lahroodi, Reference Lahroodi2007; Corlett, Reference Corlett2008; Flood, Reference Flood2008; Montmarquet, Reference Montmarquet2008; Riggs, Reference Riggs2010; Rawwas, Arjoon, & Sidani, Reference Rawwas, Arjoon and Sidani2013).

Open-mindedness is a critical trait that is normally the leading component of the epistemic virtues. To be open-minded is to be aware of one’s unreliability as a believer and to recognize the possibility that any time one is certain of something, one could be incorrect (Riggs, Reference Riggs2010). Open-mindedness consists of ‘the ability to listen carefully, the willingness to take what others say seriously,’ and the ‘willingness to entertain objections and, if appropriate, revise one’s position’ (Cohen-Cole, Reference Cohen-Cole2009: 56).

Employees who are open-minded are genuinely interested in new ideas, views, and knowledge. They tend to be resourceful, maintain a positive attitude, and rebound quickly when faced with problems or predicaments (Sharot, Reference Sharot2011). According to one study, employees can be classified relative to their understanding of where their abilities came from (Dweck, Reference Dweck2012). Those who believe that their abilities are based on innate qualities are classified as closed-minded or as having a ‘limited mindset.’ Those who believe that their abilities are based on their exploration, education, hard work, and determination are classified as open-minded or as having a ‘progressive mindset.’ Open-minded employees do not pay attention to uncertainty because of their positive outlook, admission of their mistakes, and willingness to take risks, learn from failure, and be creative (Rawwas, Arjoon, & Sidani, Reference Rawwas, Arjoon and Sidani2013).

Creativity is a non routine behavior, which requires employees’ out of the box thinking (Nusbaum & Silvia, Reference Nusbaum and Silvia2011). Employees who are high on openness to experience trait, they demonstrate an open thinking, therefore when they found trust in leader, then with high openness to experience trait, show more creativity. Research has found that employees with openness to experience are characterized as being imaginative, artistic, cultured, curious, original, and intelligent (Klein & Lee, Reference Klein and Lee2006). They are also highly motivated and seek new and challenging experiences as they have the courage to engage themselves in unfamiliar situations (Kaufman, Reference Kaufman2013).

The underlying question is why ‘openness to experience’ moderates (i.e., strengthens) the relationship between ‘trust in leader’ and ‘creativity.’ The phytology–growth theory and nitrogen productivity concept may explain this moderation effect through a three-step process: input–catalyst–output. The moderating effect of ‘openness to experience’ on the relationship between ‘trust in leader’ and ‘creativity’ may be likened to the growth of plants, which is determined by the added amounts of water and nitrogen (Ågren & Franklin, Reference Ågren and Franklin2003). To illustrate, water, as an input, is indispensable to the plant’s growth. Without water, the plant will not be able to survive. Nitrogen acts as a catalyst to accelerate or enhance the output of the process, the growth of the plant. Similarly, ‘trust in leader’ is to ‘creativity’ as water is to plants. Without ‘trust in leader,’ employees will be hesitant to come forward with ideas and communicate with the leader. They will instead prefer the more secure and less risky choice of keeping their ideas to themselves, which will hinder the growth of the organization. In contrary, if trust in the leader exists, then employees will be willing to share creative ideas without fear of repercussion. This relationship will be moderated (i.e., enhanced) by ‘openness to experience,’ exactly like the effect of nitrogen on plants. To test this moderation effect, researchers Necka and Hlawacz (Reference Nęcka and Hlawacz2013) studied the factors that inspired artists to be creative. They found that artists have a tendency to research and initiate numerous activities and ventures (i.e., openness to experience) that provide them with rich insights. This openness to new experiences will act as a catalyst to enhance the richness of the output, creativity. Accordingly, the researchers concluded in their study that those who ‘score high on activity tend to have many diverse experiences that may be used as a substrate for divergent thinking and creative activity’ (Kaufman, Reference Kaufman2013).

According to the above theories, research findings, and discussion, we may deduce that when ethical leaders are willing to communicate information with their subordinates, subordinates do not shy away from the relationship. Instead, they develop trust in their leaders, and this trust makes employees more involved and creative. This relationship is further strengthened (i.e., moderated) when employees listen carefully, consider others’ opinions seriously, and express willingness to admit their mistakes (i.e., open-mindedness). Consequently, we have formulated the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Openness to experience moderates the relationship between trust in leader and creativity, such that relationship is stronger with high openness to experience than lower.

METHOD

Sample and procedure

Data were collected under a program that aimed to look into the relationship between ethical leadership and creativity with the mediating role of trust in leader and moderating role of openness to experience in employees of fashion and designing in small textile firms in Pakistan. At the current time, the focus of small textile firms is to bring a continuous innovation in their products (Raustiala & Sprigman, Reference Raustiala and Sprigman2006; Fletcher, Reference Fletcher2013; Van der Velden, Kuusk, & Köhler, Reference Van der Velden, Kuusk and Köhler2015), which is realistically possible through employees’ creativity (Arvidsson & Niessen, Reference Arvidsson and Niessen2015). The change oriented focus of small textile firms motivated us to collect data from these firms. Before data collection, we contacted the directors of human resource departments and got their approval to distribute the questionnaire. During the face-to-face meeting, we gave them a survey letter indicating that participation is voluntary, and responses are confidential. The lead author did not know any of the subjects and made sure that they read the instructions and statement of confidentiality accompanied with the questionnaire stating that ‘Please take several minutes to complete the enclosed questionnaire. There are no rights or wrong answers to these questions, so your candor is strongly encouraged. All responses are strictly anonymous and will be only reported in aggregate. Moreover, the researcher has no means whatsoever to identify any of the respondents. Please also remember that participation in filling up this questionnaire is voluntary.’ In addition, the lead author supplied all respondents with unmarked envelopes and instructed them to place their completed questionnaires in the envelope and deposit them in a sealed box that was also supplied by the author and was left in the main lobby or employees’ cafeteria.

Accordingly, the lead author visited small textile firms and distributed questionnaires in each organization. Data were collected from two sources: employees (subordinates) and leaders (supervisors). In order to further validate the study, data were collected over a staggered period. During phase 1, employees/subordinates completed a questionnaire containing items related to ethical leadership. After 2 months, during phase 2, employees/subordinates completed a questionnaire that contained items related to trust in leader and openness to experience and leaders/supervisors filled questionnaires related to employee creativity. In order to match the employees’ responses of phase 1 to phase 2, we followed the techniques used by Carmeli et al. (Reference Carmeli, Akova, Cornaglia, Daikos, Garau, Harbarth and Giamarellou2010). During phase 1, before the distribution of questionnaires, the employees were asked to write the name of their grandparents. We clearly conveyed them its purpose which was that we will conduct an additional survey after 2 months. Respondents felt confident with this method, because it ensured their anonymity. Leaders/supervisors recognized employees through their job identity, which we took in time 1. Of the 300 questionnaires distributed, we received 230 back. The final sample included 205 questionnaires after removing 25 questionnaires due to missing data. The overall response rate was 68%.

For subordinates, the majority were male (65.9%). With respect to age category, 21% were between 18 and 25 years, 50.7% were between 26 and 33 years, 21.5% were between 34 and 41 years, 2.9% were between 42 and 49 years, and 3.9% were 50 and above years. Taking employees’ qualification into consideration, it was observed that 67.3% had an bachelor degree, 27.8% had a master degree, and 4.9% had MS/Mphil degrees. In total, 14.6% have work experience of less than 1 year, 62% have 1–5 years, 18% have 6–11 years, 2.4% have 12–17 years, and 2.9% have 18 years and above.

MEASURES

The responses regarding demographic variables, ethical leadership, trust in leader, and openness to experience were collected from employees. Employees rated 10 ethical leadership items developed by Brown, Treviño, and Harrison (Reference Brown, Treviño and Harrison2005). Sample items are ‘My supervisor can be trusted and My supervisor listens to what employees have to say.’ The α reliability of this measure was 0.90. Employees rated five ‘trust in leader’ items from the study of Anand, Chhajed, and Delfin (Reference Anand, Chhajed and Delfin2012). Sample items are ‘I trust the information supplied to me by the Leadership Team and The Leadership Team has my best interests at heart.’ The α reliability of this measure was 0.88. We used mini-International Personality Item Pool inventory to measure openness to experience and other four Big Five personality traits (Baird, Le, & Lucas, Reference Baird, Le and Lucas2006; Donnellan, Oswald, Baird, & Lucas, Reference Donnellan, Oswald, Baird and Lucas2006). The mini-International Personality Item Pool contains 20-items for measuring Big Five personality traits. Each personality trait of agreeableness, extraversion, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to experience, was measured with four items. Sample items include ‘I sympathize with others feelings,’ ‘I am the life of the party,’ ‘I Like order,’ ‘I get the assigned work done right away,’ and ‘I am interested in abstract ideas.’ The α reliability openness to experience was 0.70. The nine items rated creativity items were developed by Tierney Farmer and Graen (Reference Tierney, Farmer and Graen1999). Sample items are ‘Employee is a good source of creative ideas’ and ‘Employees suggest new ways to achieve goals or objectives.’ The α reliability of this measure was 0.86.

Control variables

We used four control variables: gender, age, qualification, and experience which significantly influence the employees’ creativity (Shin & Zhou, Reference Shin and Zhou2003, Reference Shin and Zhou2007; Carmeli & Schaubroeck, Reference Carmeli and Schaubroeck2007). We also controlled for another four of the Big Five personality traits (Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Neuroticism, and Extraversion).

RESULTS

Measurement model

Structural equation modeling through LISREL 8.80 (Jöreskog & Sörbom, Reference Jöreskog and Sörbom2006) was used to test hypotheses. Before structural equation modeling, confirmatory factor analysis was used to confirm the measurement model (Anderson & Gerbing, Reference Anderson and Gerbing1988). The measurement model consisted of four latent variables: ethical leadership, trust in leader, openness to experience, and creativity. The fit indices used to confirm the measurement model were: model χ2, comparative fit index (CFI), Truker–Lewis fit index (TLI), comparative fit index (CFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Insignificant χ2 value shows a good model fit, for CFI, TLI, IFI, the values 0.95, and above are considered as a good fit (Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999; Kline, Reference Kline2005); whereas the value of RMSEA below 0.05 indicates a good model fit (Kline, Reference Kline2005). The measurement model in Table 1 provided an excellent fit to the data then alternative model: χ2/df=1.29, CFI=0.95; TLI=94; IFI=95; RMSEA=0.03. Moreover, all the indicators loaded significantly on their respective latent factors, with factor loadings ranging from 0.51 to 1.58. These confirmatory factor analysis results show that four factor model had satisfactory discriminant validity.

Table 1 Measurement model

CFI=comparative fit index; IFI=incremental fit index; RMSEA=root mean square error of approximation; TLI=Tucker–Lewis fit index.

*p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001.

Descriptive statistics: correlations

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics as well as their zero-order correlations of all theoretical variables. Ethical leadership was significantly correlated to creativity (r=0.38, p<.01), trust in leader (r=0.35, p<.01). Trust in leader was significantly correlated to creativity (r=0.34, p<.01).

Table 2 Means, standard deviations, correlations, and significance levels

N=205.

α reliabilities are given in parentheses.

*p<.05, ** p<.01.

Gender=1 for male, 2 for female; Age=1 for less than 25 years, 2 for 25–30 years, 3 for 31–34 years, 4 for 35–40 years, 5 for 41–44 years, 6 for 45–50 years, 7 for 51–54 years; Education=1 for Bachelors, 2 for Masters and 3 for MS/Phil; Experience=1 for less than 5 years, 2 for 6–10 years, 3 for 11–15 years, 4 for greater than 15 years.

Tests of hypotheses

With acceptable measurement model and discriminant validities established, the proposed structural model was then tested. We used eight control variables (gender, age, qualification, and experience) and four personality traits agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and extraversion in the analyses and tested Hypotheses1, 2, and 3. The results are displayed in Table 3. Hypothesis1 states that ethical leadership is positively related to creativity. Results found ethical leadership was positively related to creativity, as indicated by the regression coefficient (β=0.22, p<.01), supported Hypotheses 1. Hypothesis 2 states that trust in leader mediates the relationship between ethical leadership and creativity. A 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval of 0.14–0.48 shows that there is mediation in the model and Hypotheses 2 is accepted. Hypothesis 3 states that openness to experience moderates the relationship between trust in leader and creativity, such that the relationship is stronger with high openness to experience than lower.

Table 3 The mediating effect of Trust in Leader

Note. BCa means bias corrected, 1,000-bootstrap samples; CI=confidence interval; LL=lower limit; UL=upper limit.

*p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001.

We used moderated regression analysis (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Cohen, West and Aiken2003) to test the moderating effect of openness to experience on the trust in leader-creativity relationship. For this purpose, we centered the independent and moderating variables. First, demographic variables (e.g. age, qualification and experience) was entered, second, independent and moderating variables were entered, and the third moderating variable was entered for moderation Hypothesis 2. Hypothesis 3 stats that openness to experience moderates the relationship between trust in leader and creativity, such that the relationship is stronger with high openness to experience than lower. Results rejected this relationship that an openness to experience moderate the relationship between trust in leader and creativity. There was a joint effect of trust in leader and openness to experience on creativity (β=0.04, p>.05). Hence Hypothesis 3 is rejected.

DISCUSSION

This study was conducted to find out the effect of ethical leadership on creativity with the mediating role of trust in leader and moderating role of openness to experience in employees of small textile firms in Pakistan. The current study found a significant relationship between ethical leadership and creativity. The present study confirmed the mediating role of trust in a leader on the relationship between ethical leadership and creativity. In addition, this study found the moderation of openness to experience on trust in a leader–creativity relationship.

Results depict that ethical leadership was positively related to creativity. This result is aligned with theoretical arguments that ethical leadership positively influence the individuals’ attitude and behavior (Zhu, May, & Avolio Reference Zhu, May and Avolio2004; Brown, Treviño, & Harrison Reference Brown, Treviño and Harrison2005; De Hoogh & Den Hartog, Reference De Hoogh and Den Hartog2008; Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes and Salvador2009; Kalshoven, Den Hartog, & De Hoogh, Reference Kalshoven, Den Hartog and De Hoogh2011). Moreover, the findings that ethical leadership cause positive effect on creativity, are consistent with the reasoning that ethical leadership demonstration of the values at workplace, open communication, respect to employees, fairness, trustworthiness, and balanced decision encourage employees to raise their voice (Brown, Treviño, & Harrison, Reference Brown, Treviño and Harrison2005; Brown & Treviño, Reference Brown and Treviño2006). Therefore, employees in the presence of ethical leadership, employees speak about new and novel ideas which enhance their creativity in the organization (Tu & Lu, 2013). These findings are also consistent with the findings of other researchers who found positive relationship between ethical leadership and creativity (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Cheng, Ribbens and Zhou2013; Javed et al., Reference Javed, Khan, Bashir and Arjoon2016).

Further the results of the current study shows the mediation of trust in leader between ethical leadership and creativity. Employees show trust in their leaders when they found consistency between the leaders’ observed and desired behavior. Ethical leader with ethical behavior show normatively appropriate conduct which employees like in the best interest of organization. Therefore, leadership with ethical behavior is trusted by employees at work setting (van den Akker et al., Reference van den Akker, Heres, Lasthuizen and Six2009; Yozgat & Meşekıran, Reference Yozgat and Meşekıran2016). Employees having trust in leader tend to exhibit creative behavior. This is because creativity is a risk taking behavior, where employees experience threat from their leader, because in the standardized work setting, top leaders only respect the confirmation of standardized norms. In such a work setting, employees also feel a fear of being rejected by leaders because controlling leadership sees creativity as deviant behavior at work setting. Moreover, not all ideas guarantee success because a large majority of the ideas fail (Gong, Cheung, Wang, & Huang, Reference Gong, Cheung, Wang and Huang2012). Therefore, before showing such risky behavior involving creativity, employees first see that whether they trust on leader, that leader will not punish them if they speak about new work means, via generating new ideas. If they feel confident and trust on the leader, then they exhibit creativity behavior (Piccolo et al., Reference Piccolo, Greenbaum, Hartog and Folger2010; Walumbwa, Mayer, Wang, Wang, Workman, & Christensen, Reference Walumbwa, Mayer, Wang, Wang, Workman and Christensen2011; Hahn, Lee, & Jo, Reference Hahn, Lee and Jo2012). Therefore, the present study found mediation of trust in the leader between ethical leadership and creativity. In addition, results of a current study did not establish the moderating effect of openness to experience between trust in leader and creativity. Openness to experience is a personality dimension, that help employees to look beyond the traditional job methods. As employees with openness to experience show imaginative thinking which helps them to show creativity (King, Walker, & Broyles, Reference King, Walker and Broyles1996; Nusbaum & Silvia, Reference Nusbaum and Silvia2011; Kaufman & Paul, Reference Kaufman and Paul2014) when they repose trust in their leader. However, the non significant moderating effect of openness to experience indicate that employees of small textile firms scored low on their openness to experience trait.

IMPLICATIONS

This study contributes to the existing body of knowledge in many ways. First, it encourages and strengthens our understanding of the influence of dynamics of ethical leadership on employee creativity. Studies confirmed that ethical leadership increases employee creativity, but the mechanism of trust in the leader between ethical leadership and creativity is the new contribution of this study.

The current study has several managerial implications. In their endeavor to promote creativity, leaders should clearly articulate a moral vision that inspires employees to take on greater moral responsibility and risk for their work at all organizational levels. This would help in fostering employee trust, creating a supportive atmosphere, and engaging in confidence building practices, which would then further result in greater awareness of employee creativity (Conger, Reference Conger1989; Quinn & Spreitzer, Reference Quinn and Spreitzer1997). A high level of trust would ensure that ethical leaders have a positive effect on levels of employee creativity.

To compete in the market, every organization acquires resources that help to achieve and sustain competitive advantage. Organizations in the market face opportunities and threats and to avail of these opportunities and to avoid the threats, organizations demand resources which enable them to deal with them effectively. All resources have their own benefits, but human resources are the backbone of the organization that bring creativity and innovation in the organization to avail of opportunities and to avoid threats. Social capital theory (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, Reference Nahapiet and Ghoshal1998) described that human resources have also economic value at work place and their value is determined by their knowledge, skills, and abilities, and with other characteristics. Openness to experience shows economic value which is determined by their creative and innovative behavior to help organizations achieve competitive advantage. The current study provides complete insight to organization and how they can enhance personality of their employees to become imaginative, cultured, curious, original, broad-minded, intelligent, and artistic to develop creative ideas and implement those creative ideas to bring innovation in the organization so to achieve sustainable competitive advantage in the marketplace.

This study provides complete insight into organizations and how they are able to meet the challenges of a changing and dynamic environment. A changing environment results in enhanced competitive activity in the market. To sustain competitive advantage in the market, organizations need competent employees who possess the ability to generate new and creative ideas according to the changes. Inimitable and nonsubstitutable human resource helps organization to gain and maintain competitive advantage. The organization requires creative people who have the ability to develop and implement creative ideas to bring innovation and to meet the changing needs of customers, and thus foster an innovative and creative culture within the organization. Creative minds require an open mind to explore, tolerate, and consider new and unfamiliar ideas and experiences (McCrae & Costa, Reference McCrae and Costa1987). The current study will help organizations to enhance learning, foster a creative and innovative culture to cope with the changes of a dynamic environment and to sustain competitive advantage in the market. Unstable and uncertain conditions in the environment, faced by small textile firms resulted in a lack of innovation, motivation, initiative, hardworking, dedication, devotion, carefulness, creativity, efficiency, effectiveness, and concentration in employees. This study will help small textile firms overcome this gap by enhancing learning, encourage a creative and innovative culture to cope with the changes of environment, and to sustain competitive advantage in the market.

STRENGTHS, LIMITATIONS, AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The current study has a strong methodological approach. First, in order to reduce the potential effects of common methods and single source bias, we collected data related to ethical leadership and trust in leader from employees. Moreover, responses regarding employee creativity were taken from leaders which further reduces the effects of common method and single source bias. Second, we collected leaders’ responses and employees’ responses with a time lag of two months, which resulted in a better understanding of the relationships among the studied constructs.

However, there are few limitations of this study that needs attention. First, we examined the relationship between ethical leadership and creativity with mediating role of trust in leader and moderating role of openness to experience. However, there are many other mediating and moderating factors that can play an important role between ethical leadership and creativity. Therefore, we recommend future researchers to study mediating and moderating variables between ethical leadership and creativity.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Professor Sajid Bashir for his directions. The authors also acknowledge the editorial comments of this journal.