Introduction

In Brookby, Auckland, two similar small private firms seek resource consent to expand their operations. The firms are both involved in natural resource development; one is a quarry and the other is involved in clean fill waste. The proposed developments are examples of locally unwanted land use (LULU). After the 3 years of initial notification of the proposed expansions one firm is fully functioning at its anticipated level of operation while the second is still locked in legal battles with the community. Why did one project proceed as planned, and the other project experience expensive delays? This paper examines this conundrum using three theoretical lenses: stakeholder theory, the not-in-my-backyard (NIMBY) phenomena and the legislative framework. It suggests approaches to address the growing problem of community resistance that can threaten small business development. It explores avenues small business might pursue to achieve the ideal outcome of any expansion – the support or at least informed consent of those directly affected by the project.

The study presented in this paper helps deepen the knowledge of the LULU phenomena. We suggest three reasons why LULU might be of interest to management researchers. First, the management discipline has traditionally been concerned with concepts of operations planning, performance measurement, waste reduction, quality, power, accountability, stakeholder engagement and leadership. These concepts are critical in the debate over land uses or development projects which are regionally or nationally needed or wanted but are considered by many people who live near them as objectionable. Management researchers can leverage their understanding of these concepts to make substantive contributions to research efforts that seek to further the understanding of the LULU phenomena. Second, a better understanding the complexity of LULU issues is essential for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) to appreciate and respond to their local neighbourhood concerns. Third, as the LULU phenomena is highly complex and involves a wide range of participants a multidisciplinary approach which includes management academics is appropriate to bring greater clarity. BANANA – Build Absolutely Nothing Anywhere Near Anything – is not a practical solution.

The paper demonstrates the value of combining stakeholder theory and NIMBY research within the modifying context of resource management legislation. Although we acknowledge some overlap we view each of these perspectives as offering different insights into the LULU challenge. The focus of stakeholder theory is broad and based on the firm, considering how it may, could or should engage with stakeholders with a view to ensuring survival or for analysing an outcome or strategy (Freeman, Reference Freeman1984; Evans & Freeman, Reference Evans and Freeman1988; Donaldson & Preston, Reference Donaldson and Preston1995). The focus of NIMBY research is narrower and includes only one stakeholder group – the protesters, for example, some scholars have described NIMBY responses as purely self-interest others have suggested that NIMBY responses give the demonstrators a democratic voice (Schively, Reference Scharff2007). The focus of the legislative framework is around distributive justice and around the generation of a neutral political process in which affected citizens and businesses can be heard (Brion, Reference Brion1988; Esaiasson, 2014).

There are parallels in the way stakeholder theory, NIMBY research and resource management legislation have evolved. Land use disputes are not new (Eranti, 2017). Philo’s (Reference Philo1987) seminal paper ‘Not at our seaside’: documents community opposition to a 19th-century branch asylum. Community involvement in local authority processes began in the late 1960s to, among other things, encourage public authorities to become more responsive to public concerns, resolve conflict and improve the success of policy implementation (Kraft & Clary, Reference Kraft and Clary1991). The New Zealand Resource Management Act (RMA) was passed in 1991 to promote the sustainable management of natural and physical resources such as land, air and water.

Similarly, stakeholder theory developed out of a time of fundamental change and turbulence in business (Savage, Nix, Whitehead, & Blair, Reference Sandman1991). External stakeholders started to demand a voice in organisational governance, planning, operations and became concerned about raising the level of corporate social responsibility (Savage et al., Reference Sandman1991). Stakeholders became recognised by business as a force that had to be ‘managed’. The term NIMBY which describes a defensive reaction by community residents to unwanted land uses for a specific property was first introduced by Dear and Taylor’s (Reference Dear and Taylor1982) paper ‘Not on our street’ (Schively, Reference Scharff2007; Esaiasson, 2014). NIMBYism, continued to gain prominence in the 1980s – as populations grew so did the number of interests and opinions and the desire to understand the motivation behind the protests (Eranti, 2017).

There is some evidence to suggest that NIMBYism is increasing. The Saint Index, a survey of attitudes to land use in the United States finds distrust and cynicism over the process by which local land use decisions are made and that concern about the impact of new development on home values is a significant factor in explaining this increased resistence (The Saint Consulting Group, Reference Takahashi and Dearn.d.). This means it is likely to be difficult for a private firm to apply for the permits for expansion without the local community undertaking some form of protest (Sellers, Reference Schwarz1993). Almost 20% of Americans (or someone in their family) have actively opposed a new development project in their community (The Saint Consulting Group, Reference Takahashi and Dearn.d.). LULUs can be divided into three industry types (1) waste disposal facilities, primarily landfills and incinerators (2) low-income housing and (3) social services such as mental health and addiction services, group homes and shelters for the homeless (Gerrar, Reference Gerrar1993). The Saint Index finds landfills are the most disliked type of LULU and quarries are the third-most-disliked LULU.

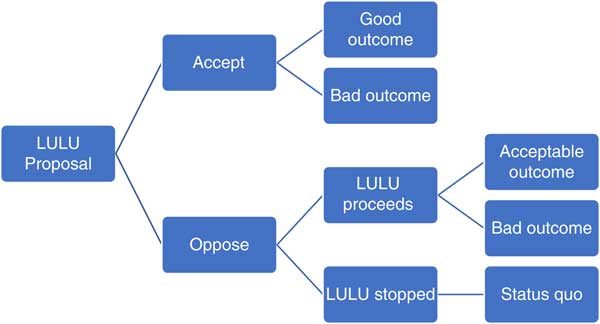

O’Hare (Reference O’Hare2010) describes the development of opposition to a LULU (Figure 1). When a LULU is proposed neighbours face a decision whether to accept it or to oppose it. Accepting the LULU may lead to two possible project outcomes ‘good’ or ‘bad’. Opposing the LULU incurs costs (e.g., time, attention, stress and money) and may also result in two outcomes, ‘LULU proceeds’ and ‘LULU stopped’. In turn, if the LULU proceeds the outcomes may be perceived as acceptable or bad. The decision tree is based on perceived probabilities and perceived benefits and costs, but little is known as to why, when two similar LULU projects are proposed, one might be accepted and the other opposed.

Figure 1 Decision tree outlining possible actions and outcomes for project neighbours (adapted from O’Hare, 2010)

We present two case studies of private firms seeking to expand their business against the wishes of some members of their local community. The firms operate in the same geographic locality, conduct their stakeholder engagement within the same time period, for the same purpose and within a similar and close demography. Both firm’s operations and plans for expansion require legislative consents. We compare the differing approaches of the two SMEs and analyse the reasons behind their significantly dissimilar outcomes. We use four sources of data: observation, informal discussions, archival data and e-mails. The paper is organised as follows: The first section presents the theoretical background, including stakeholder theory, NIMBY phenomena and the legislative framework. The second section describes the research method. The third section describes the results and the fourth sections discussion completes the analysis. We conclude the paper with an overview including limitations of the study and recommendations for future research.

STAKEHOLDER THEORY

Since the 1980s management researchers have emphasised the importance of stakeholders in the success of business operations (Cleland, Reference Cleland1988; Savage et al., Reference Sandman1991; Beringer, Jonas, & Kock, 2013; Missonier and Loufrani-Fedida, Reference Missonier and Loufrani-Fedida2014; Littau, Jujagiri, & Adlbrecht, Reference Littau, Jujagiri and Adlbrecht2010). Stakeholder theory has developed from an interdisciplinary research base, with the view ‘to explain and predict how organisations function with respect to stakeholder influences’ (Rowley, Reference Rowley1997: 895).

Stakeholder theory, has as its focus, large publicly owned corporations (Laplume, Sonpar, & Litz, Reference Laplume, Sonpar and Litz2008). Despite small business comprising 99.8% of all enterprises, 57.4% of value added and 66.8% of employment in the nonfinancial business sector in Europe and 95% of business worldwide, little research has been undertaken to understand how stakeholder theory might impact this business group (Muller, Devnani, Julius, Gagliardi, & Marzocchi, Reference Muller, Devnani, Julius, Gagliardi and Marzocchi2015; Westrenius & Barnes, Reference Westrenius and Barnes2015). For instance, ownership and control are not normally separated in the small business (Spence, Reference Sellers2016), they are often independently owned and operated, have operations closely monitored by the owner who at the same time strongly influences decision-making and is the source of much of the operating capital (Schaper, Volery, Weber, & Lewis, Reference Savage, Nix, Whitehead and Blair2011).

Generally, stakeholder theory advocates that to ensure survival and success in the long term, firms should consider the impacts of their actions on all stakeholder groups (Collier, Reference Collier2008). Firms are expected to take stakeholders’ demands into account when engaging in a strategic management process (Roberts, Reference Roberts1992; Mitchell, Agle, & Wood, Reference Mitchell, Agle and Wood1997). Ferreira and Otley (Reference Ferreira and Otley2009) advise that when stakeholders have explicit environmental expectations, firms should address these expectations by paying attention to all their relevant stakeholders.

Herein lies a problem, although a stake is defined as an ‘interest’, ‘claim’ or ‘share’ in an organisation’

(Mallik & Mitra, Reference Mallik and Mitra2009: 10) there is no consensus on exactly who these stakeholders are (Wang, Jiaoju, & Qiang, Reference Wang, Jiaoju and Qiang2012). Wide definitions are of little value to a small firm with limited resources for example, Freeman defines a stakeholder as ‘any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievement of a corporation’s purpose’ (Freeman, Reference Freeman1984: 46) while Starik (Reference Spence1995) argues for stakeholder status for nonhuman nature including trees. The development of the more specific action of ‘stakeholder analysis’ provides a range of criteria that justify the inclusion of various stakeholders and provide a set of tools to generate knowledge about their actions (Wang, Jiaoju, & Qiang, Reference Wang, Jiaoju and Qiang2012). Stakeholder analysis is found to be useful in understanding the behaviour, intentions, interrelations and interests of stakeholders from the perspective of the firm which can guide the formulation of strategy and facilitate project implementation though (Brugha & Varvasovszky, Reference Brugha and Varvasovszky2000; Wang, Jiaoju, & Qiang, Reference Wang, Jiaoju and Qiang2012). Disappointingly most studies concentrate on the participation and influence of stakeholders rather than investigating how to effectively manage stakeholder actions (Wang, Jiaoju, & Qiang, Reference Wang, Jiaoju and Qiang2012). As a tool for addressing LULU stakeholder analysis is at the same time too wide and too narrow. It is too wide in that it suggests an analysis of all stakeholders rather than just those protesting the development while laudable this does not assist the small business owner with limited resources. At the same time, it takes the perspective of business which may limit the insights that may be gained from other perspectives. We turn now to the research into the NIMBY phenomena which we suggest will address these shortfalls.

THE NIMBY PHENOMENA

NIMBY research offers a worthwhile perspective for stakeholder theory advancement. As the name suggests NIMBY research is undertaken using the perspective of the protester. Many development projects that are needed or wanted by society are unacceptable to the people who live near them (Popper, Reference Popper1985). A community will oppose LULUs in their neighbourhood for what appears to others as self-interested and parochial reasons (Hall, Reference Hall1989; Esaiasson, 2014). Protesters perceive LULUs as providing few direct benefits to them, while presenting many risks along with an unacceptable change to the status quo (Petts, Reference Petts2014). These NIMBY views are fuelled by the subjective feeling of being put at a disadvantage due to the siting of the proposed project which can be solved only by redirecting this disadvantage to unspecified others (Scharff, 2004). They seldom provide a reason as to why another group should accept the disadvantage in their stead or why another location is more favourable than the proposed one. In many instances people may be aware of the need for the new project but do not want it to take place near their homes (Kaya & Erol, Reference Kaya and Erol2016). The resulting mixture of public good and private bad is the basis of NIMBY conflicts which present in various forms, for example, as conflict between local interests and societal interests, between locally concentrated costs and dispersed of societal benefits, between material progress and protection of local communities or between economic growth and environmental protection (Lake, Reference Lake1993; Frey, Oberhoizer-Gee, & Eichenberger, Reference Frey, Oberhoizer-Gee and Eichenberger1996).

Conflict is driven by fear of possible external effects. The list of possible external effects is long but may include, increased density, pollution, traffic, odour, dust, vibration, health risks, property values decline and the inability to prevent future LULUs (Sandman, 1990; Kaya & Erol, Reference Kaya and Erol2016). Conflict resolution requires an understanding of the nature of these factors and their effects as perceived by the protesters (Takahashi & Dear, Reference Starik1997; Kaya & Erol, Reference Kaya and Erol2016). Perceived effects will be greater for hazards which are involuntary, uncontrollable, harmful, delayed, impacting on children and are man-made (Petts, Reference Petts2014). The magnitude of the risks perceived by protesters are often different to the magnitude of the risks formally assessed on a scientific basis (Kasperson, Golding, & Tuler, Reference Kasperson, Golding and Tuler1992; Kaya & Erol, Reference Kaya and Erol2016). Studies of resource consent hearings, find protesting groups can be successful in challenging the scientific information about risks that are provided during the siting process by detailed questioning the data, methodology, and technical aspects of siting plans which provide evidence different to what they perceive as correct (Kearney & Smith, Reference Kearney and Smith1994). NIMBY resistance is frequently stronger for long term as opposed to shorter-term projects. Projects that have a long operating life have a lasting cumulative effect, since, once the location is devalued by the first LULU, even more LULUs can be justified – with resulting further devaluation (Petts, 2004).

The NIMBY literature provides some insights as to why some NIMBY responses are stronger than others even when the threats, from an outsider’s view, might seem the same. Within a LULU conflict situation, there may be many individuals, with distinctly different characteristics and perspectives, their approaches to the problem and to each other may cause variance in approaches and to the resulting outcome (Kaya & Erol, Reference Kaya and Erol2016).

Trust is related to qualities such as honesty, openness and concern for others, people are less likely to oppose a LULU if they trust the attitudes, motives and honesty of the others involved (Schively, Reference Scharff2007). Distrust may be related to existing examples of untrustworthy behaviour such as failure to meet resource consent obligations (Kaya & Erol, Reference Kaya and Erol2016). Petts (Reference Petts1992) finds a lack of trust stems from three factors, first a lack of trust in private industry to consider safety and the environment as seriously as making a profit; secondly a lack of trust in regulatory systems to develop appropriate strategies for managing risks; and thirdly a lack of trust in those charged with monitoring the effects. Trust can also be portrayed in the way expert’s present information about the LULU. Taking a strategy that adopts from the beginning, an open and honest communication about the project and the consequence for the surrounding environment, builds trust but as (Schwarz, Reference Schively2004: 22) caution ‘As soon as this starts one should be prepared for increasing involvement of people’. Futrell (Reference Futrell2003: 365) identifies the dangers in presenting ‘conflicting, contradictory, multiparty, multidirectional communications that fail to clarify the risks associated with a project’. Disagreements among technical experts are likely to heighten conflict due to causing public confusion (Covello & Mumpower, Reference Covello and Mumpower1985). The media can also influence the intensity of the NIMBY response by promoting the NIMBY action groups actions and perspectives (Bassett, Griffiths, & Smith, Reference Bassett, Griffiths and Smith2002; Rogge, Dessein, & Gulinck, Reference Rogge, Dessein and Gulinck2011; Kaya & Erol, Reference Kaya and Erol2016). Following a review of the NIMBY literature on waste management initiatives Petts (Reference Petts2014: 1) concludes:

While a psychological and social element is identifiable in public concern, it is primarily a practical manifestation of deeper problems, in particular a loss of trust in industry and regulators, a failure to communicate information effectively by the latter, and problems in decision-making processes which either exclude the public from decisions or involve them too late.

Much NIMBY literature seeks to identify ways to address LULU conflicts. Kaya and Erol (Reference Kaya and Erol2016) suggest two key strategies. The first is to address any technical or ethical concerns by actions such as considering positioning and external effects or by offering compensation. The second suggested strategy is to improve the participatory process by increasing collaboration and consensus building or mediation. Schively (Reference Scharff2007) recommends providing a means for those impacted by LULUs to maintain control, such as agreements to sit on monitoring committees or to select experts to monitor negative impacts. Being transparent in all aspects of the business including economic, social and ecological performance measures can be helpful (Artois, 2004). As Schwarz observes ‘The major consideration is to stop the mechanisms that lead to a situation in which conciliatory discussions between protesters and management are no longer possible’ (Reference Schively2004: 20).

THE LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK

NIMBY conflicts may be viewed as contributing to democratic land-use processes (Mannarini & Roccato, Reference Mannarini and Roccato2011), and as such having a greater role than an inevitable outcome of affected private interests (Kempton et al., 2005; Bell, Gray & Haggett, Reference Bell, Gray, Haggett and Swaffield2013; Eranti, 2017).

Decision-making around the land use process becomes more complex where community interests are prevalent (Kaya & Erol, Reference Kaya and Erol2016), however community resistance can also be an outcome of a failed process, rather than the cause of a failed process, particularly when planning authorities break the line of trust between themselves and affected communities (see, e.g., Kraft & Clary, Reference Kraft and Clary1991; Groothuis & Miller, Reference Groothuis and Miller1997). The question is then whether the behaviours described as NIMBYism are causal of a failed process, or, symptomatic of a systemically flawed process.

In this paper the two subject companies are affected by NIMBY behaviour. The process is the RMA 1990. We ask whether the processes followed by the subjects in response to the legislative requirements disclose a process that responds to or is causal of some or all the NIMBY actions. The response we focus on is the extent and quality of the stakeholder engagement of the two companies, one being a wide engagement, the other limiting engagement to the minimum prescriptively required by the RMA. If the RMA allows outcomes that are causal of NIMBY action it can be seen as a failed process. Failure in this context is the extended time and disputes in finding the community and commercial balance under which the projects could proceed.

Is the RMA a flawed process in terms of stakeholder engagement? It is a process that will modify the companies’ compliance behaviour and empower communities, but does it also promote approaches that limit or negate stakeholder engagement and precipitate NIMBY behaviour?

The legislative context in New Zealand is contained in the Resource Management Act (RMA), 1991. The act categorises uses as permitted or requiring consent. The activity of quarrying is not a permitted activity and so required consents (s.9) with quarries specifically mentioned (s.10) activating the systems for community notification, consultation, objection, local authority decision-making and appeals of that decision.

The RMA is both prescriptive and policy based, driven by its primary purpose ‘to promote the sustainable management of natural and physical resources’ with the secondary aim of enabling ‘people and communities to provide for their social, economic, and cultural well-being and for their health and safety’ (s.5(2)) with reference to s.(6 &7) to principles for environmental, cultural, ecosystem and efficient land use. This will lead to competing interests.

In considering competing interests, the Supreme Court has ruled that a ‘balanced judgement’ is not acceptable (Environmental Defence Society Inc v The New Zealand King Salmon Co Ltd [2014] NZSC 38). Compliance is not achieved by balancing interests. This approach promotes all interests, and therefore, all stakeholder’s interests in a way which means they cannot be individually submerged.

The import of this is that the legislation requires a wide view of stakeholder engagement and suggests considering all needs would be a motivation in engagement. However, caution is needed in linking the engagement directly to the Supreme Court position.

The organisations had obligations under the RMA to mitigate the potential environmental impacts using the most practicable available method, coupled to local authority requirements to develop a quality management plan to demonstrate how they will manage the mitigation (Auckland Council). These actions could be a response to community pressure but may also simply be compliance.

The Consenting authority will determine the notification requirements, which is its stakeholder identification process. These are not necessary all affected parties (stakeholders) and omissions may occur.

To protect all stakeholders an appeal of the consenting authority decision by disaffected parties to the Environment Court (s.120) is a de novo appeal. This type of appeal has two affects relevant to stakeholder strategy decisions. This creates an opportunity for stakeholders to ‘have another go’ or start an appeal as though it had not been heard by the regulatory authority. No part of the original hearing carries forward creating the same uncertainty that prevailed before the consent application.

Coupled to the earlier court rejection of a balanced approach (majority view) this would suggest an applicant would be advised to determine all affected parties and engage widely. The stakeholder engagement would ideally achieve consent; however, the fact of engagement and the identification of the affects would assist in the generation of the quality management plan and would be a significant factor in the initial hearing and in any Environment Court determination. This would appear good commercial sense considering the statutory scheme. There is however, no obligation to go any wider than prescribed or identified by the consenting authority. The organisation is reliant of the consenting authority casting the net carefully.

In larger firms this appears to be recognised and is reflected in policy statements where statements abound for with a proclaimed desire to ‘meet community as well as regulatory expectations’ (Mighty River Power, 2012). This is not to suggest these statements are hollow as the companies take significant steps to give substance to such statements. Meridian also refer to community engagement and projects in the areas affected by their activities in their sustainability reporting (Meridian Energy, 2013). The stakeholder analysis of both companies is wider than indicated by the RMA.

The SME sector does not appear to make this link, nor were we able to find any literature linking sustainability policy, stakeholder analysis and legislative frameworks relating to the SME sector. This is perhaps hardly surprising given the internal sophistication implied and the resources required. This level of engagement is far from business as usual in the SME sector and represents significant cost and risk.

The RMA legislative framework is compulsory. Whether firms engage at the other levels in anticipation of the compulsory, or, as adherents to stakeholder engagement is a key question in understanding the strategy followed in the reviewed case studies. It may also be that some will recognise the issues noted and the extent to which the legislative framework will recognise the noncompulsory engagements undertaken, a strategy which obfuscates the issue. In the examples drawn from larger power producers and their public statements (see, e.g., Mercury Energy, 2016), they appear to merge good stakeholder practice with the legislative framework. Whether this is in recognition of this overlap or whether their other motivations for branding and sustainability drive processes which necessarily incorporate both good stakeholder practice and legislative compliance is speculative.

The behaviours observed in the two organisations are markedly different. One, a wide stakeholder engagement, the other, a prescriptive approach dictated by the explicit needs of the RMA and limited its strategy to the minimum requirements of the act, excluding the wide stakeholder engagement.

The question is the extent to which the RMA precipitates NIMBY behaviours. It most certainly facilitates it, a factor the organisations are undoubtedly aware of. The almost polar opposite approaches have resulted in a successful outcome for one, and problems for the other. The latter would view the process as flawed, but is it the system or their use of it? The RMA process does not prevent wide engagement. It encourages it and the courts dictate it.

What can be seen is that a limited and prescriptive approach negates stakeholder engagement, and, the appeals process empowers disaffected NIMBY behaviours. It can therefore be argued that the RMA promotes stakeholder engagement where the parties are sophisticated, understand the way in which policy-based legislation is applied, and are well advised. These are the attributes of larger or experienced organisations. Most SMEs are unlikely to be included is such a category.

Is this a flawed system? For the SME which expects law to be clear, prescriptive and provide a step by step mechanism to be narrowly followed and thereby achieve an outcome, it is. From the perspective of inclusion of all stakeholders, providing a range of mechanisms to address its own primary environmental and social objectives, and to audit the actions of local authorities, it is very effective.

MOTIVATION TO ENGAGE IN STAKEHOLDER ACTIVITY

Schwarz examines the reduction in NIMBY and acceptance of waste incinerators and report:

Measures aiming at the public to reach increased acceptance only work if they are taken before the formal discussions concerning the decision-making (spatial planning, plan definition). These measures do not work if they are taken simultaneously with public-oriented actions by opponents. The latter group can bring to the fore their arguments more easily and more emotionally and thus find a willing ear with the press (Reference Schively2004: 19).

The reasons for a firm to engage in a stakeholder-driven strategy are numerous. It is rare that business engage in activities which are truly altruistic. Stakeholder engagement has a motivating ranging from the altruistic to the compulsory. We suggest that all engagement beyond the altruistic is motivated by self-interests. Closely linked to stakeholders’ interests is the notion of legitimacy, which can be achieved when there is alignment between the social values associated with the firms’ activities and the norms of acceptable behaviour in the participating community (Dowling & Pfeffer, Reference Dowling and Pfeffer1975; O’Donovan, Reference O’Donovan2002).

Motivation can be viewed as a scale which is tiered into layers starting with a desire to understand the business environment, a need to engage with a particular group, a standard or professionally based expectation, a professional or regulatory body promulgations and finally to a legislative imperative. The upper end of this scale can be described as compulsory

The RMA legislative framework is compulsory. Whether firms engage at the other levels in anticipation of the compulsory, or, as adherents to stakeholder engagement is a key question in understanding the strategy followed in the reviewed case studies. It may also be that some will recognise this scale and the extent to which the legislative framework will recognise the noncompulsory engagements undertaken, a strategy which obfuscates the issue. In the examples drawn from larger power producers and their public statements (see, e.g., Mercury Energy, 2016), they appear to merge good stakeholder practice with the legislative framework. Whether this is in recognition of this overlap or their other motivations for branding and sustainability drive processes which necessarily incorporate both good stakeholder practice and legislative compliance is speculative.

METHOD

We select a case study research design to examine decision-making around stakeholder engagement during RMA processes. We select the two firms because of their similarities in terms of location size activities and plans for expansion. We use four sources of data: observation, informal discussions, archival data and e-mails. We attend one planning meeting at Brookby Quarry, five local board led community representative’s meetings, two public meetings organised by the Brookby Environment Protection Society and the Annual General Meeting of the neighbouring Whitford Residents and Ratepayers Association. Both cases were discussed at these meetings which resulted in decisions being made regarding residents’ future actions. We conduct participatory observation of the various actors and document our observations. We meet with and gain insights from: the chairperson of the Brookby Environment Protection Society, the chairperson of the Whitford Residents and Ratepayers Association and a community representative on the Brookby Quarry Community Liaison Group. We collect data from the archives of the council, library and newspapers and search the web-based archives of national and local newspapers, related organisations and blogs. We note the opinions expressed in these documents. We gather more than 15 e-mails shared by a local body representative who served this area during the period of the resource consent applications.

We perform the data analysis in two stages. First, we critically examine each case to understand the specific organisational context and stakeholder interactions (Yin, Reference Yin2014). Next, we analyse the findings to identify themes, patterns and trends. Barratt, Choi, and Li advise a good means to analyse qualitative case study data is to ‘select a few constructs based on the extant literature that describes the phenomenon of interest and then look for the evidences that address these constructs’ (Reference Barratt, Choi and Li2011: 331). Accordingly, we compare our data with the constructs from the three theoretical foundations previously outlined; stakeholder analysis, the NIMBY phenomena and the legislative framework. Before reporting the results in these constructs, we provide a synopsis of the two cases.

Case one: Brookby Quarry

Brookby Quarry has been in operation with various ownership structures since 1940. It produces and supplies up to 3.5 million tonnes per annum of base-course, concrete aggregate, asphalt and sealing chip (Brookby Quarries Limited, 2014). The location of the quarry, ease of extraction and its superior quality aggregate resource, allows it to remain competitive within the Auckland market.

Application for resource consent

In a 2013 application to the Auckland Council Brookby Quarries Ltd requested the following:

Truck movements

From an existing daily limit of 360 truck movements (weekdays) – an average of 36 an hour and a current hourly limit is 80 truck movements, the quarry requested no set daily limit, an hourly limit of 120 truck movements, and a weekly limit of 5120 truck movements.

Production

The quarry requested increasing extraction rates from 600 to 1000 tonnes an hour, using bigger, rather than more, blasts. Increased processing limits from 550 to 1000 tonnes an hour.

Hours

Extend hours of work from half-days to full days on Saturdays and weekday operations from

4.30 to 7 p.m.

Environmental Court decision

The environment court decision issued on the 18th December 2014 permits the production from the Brookby Quarry to increase from around 1.3 million tonnes per year to between 3.9 and 4.6 million tonnes annually. The new consent was given effect to on 5 January 2015. There was very little difference between what was asked for in the original application and what was eventually granted.

Case two: Pascoe’s Cleanfill (P&I Pascoe Limited, 2015)

P & I Pascoe Limited has been an incorporated family business since 2000. The company specialises in earthworks and aggregate related activities and operate a clean fill operation at Clevedon under resource consents which expire in 2020.

Application for resource consent

In 2013, P & I Pascoe Limited proposed to undertake a clean fill operation on a property located on Twilight Road, Brookby. The proposed clean fill will operate for up to 20 years and will fill a gully on the site that is ~4 ha in area. Truck movements have been estimated at 80 vehicles per day on average and 120 vehicles per day at maximum usage. No new entrances into the property are proposed. The fill would come from P & I Pascoe Limited’s earthworks as well as other companies and council works across South Auckland.

Environmental Court decision

On 29 January 2015 the Environment Court was satisfied that the adverse effects of the proposal could be managed to the point where they were acceptable, and that the positive effects would outweigh any disadvantages remaining. Subject to a satisfactory resolution of the remaining issues and of the draft conditions, the Court concluded that the consents should be granted.

The satisfactory resolution of the remaining issues and of the draft conditions are still being negotiated. Compromise was achieved through expert and legal counsel at considerable expense to both parties and with numerous delays and court extensions. Some of the compromises reached through this drawn out process included the following: only one end of the entrance road – Twilight road to be used by clean fill trucks. The hours of clean fill operation limited to 5 hr/d to meet noise requirements. And significant roading upgrades are required on Twilight Road. The Brookby Environment Protection Society constantly monitors P & I Pascoe Limited activities to ensure consent conditions are being adhered to, and to raise any issues with Auckland Council.

FINDINGS STAKEHOLDER ANALYSIS

We identify the stakeholders using the three criteria advocated by Mitchell, Agle, and Wood (Reference Mitchell, Agle and Wood1997) described earlier. Those who have power are deemed legitimate and can muster urgency. There are three external stakeholders which meet these criteria: (1) the Auckland Council who manage the consenting process and require the services of both operations to meet their infrastructure requirements, (2) the local community residents who will be affected by the increase in truck movements and are represented by The Brookby Environment Protection Society (BEPS) and (3) the people of the wider Auckland community who require the services of these firms to meet their housing demands.

FINDINGS NIMBY PHENOMENA

Our case study comparison focusses on two key issues relative to the NIMBY response – the influence of perceptions in shaping the NIMBY responses, and methods used to address the NIMBY response.

Relationship with the community: Brookby Quarry

Building relationships

Despite undertaking activities which can be controversial in nature the Brookby Quarry has attempted to build a positive relationship with its community (Brookby Quarries Limited, 2014).

Maintaining community control

Since 2000 Brookby Quarry has operated a Community Liaison Group which meets regularly to discuss with quarry management the operations and effects of the quarry on the community. Along with management and local residents the group members include Auckland Council and Iwi representatives, allowing it opportunity to disseminate information, hear community concerns and discuss ways of addressing those concerns.

Transparency

The quarry is proactive in sharing information on quarry activities that may impact on the surrounding property owners for example mail drops of intended blasts and public information evenings (Brookby Quarries Limited, 2014). Local residents were informed by the quarry before an application for resource consent was made with council.

Compensation

The Brookby Quarry has volunteered to make improvements to improve the community environment including installing sound stopping bunds and planting these with bee and bird friendly native bush. It is active in seeking community input into ways it can better assist the local community (e.g., the forming of walkways and mountain bike paths on some of its unused land).

Compromises

Consultation with local residents and community groups led to several compromises. These included loadout truck hours to end at 5.30 p.m. on weekdays and 12 p.m. on Saturdays. A truck movement maximum of 902 per day (an average of 82 truck movements per hour over the working day but with a maximum of 100 in any 1 hr). A 50 km/hr speed limit on the full length of the access road with sealed hard shoulders on feeder roads to improve road safety. The staging of truck movements on Saturdays to consider weekend recreational road use. Initially only 10 trucks in and 10 trucks out allowed on Saturdays.

Relationship with the community P & I Pascoe Limited

Relationships not established

The proposed site in Brookby is new and therefore a relationship with the community was not established. P & I Pascoe Limited own a nearby clean fill (Creighton’s Road, Clevedon) which is well known for its poor relationship with its neighbours.

Loss of trust

About the time of its application for a resource consent in Brookby its existing Creighton’s Road premise was issued an abatement notice because of the company exceeding their consented number of truck movements per day. This disregard for the operating conditions imposed by Council, was viewed by the residents of Brookby as a warning of what might happen to them.

Lack of information

There were conflicting regulatory requirements on the question of whether the proposed consent was notifiable. Under the district plan provisions, the proposal was a discretionary activity. However, under the regional plan consent was required for a noncomplying activity. The initial application was initially attempted as a non-notified application something which local residents regarded as underhand (Henry, Reference Henry2013). Local community members expressed concern over the perceived secrecy of the proposal. P & I Pascoe Limited report they informed the community of their intentions by leaving CDs in neighbouring letter boxes outlining the proposal and offering a guided tour of the site to interested parties even though no one took them up on the offer (Henry, Reference Henry2013). There are conflicting stories over how many properties received this CD. Public meetings were not called. Local community objections were centred on the perceived secrecy of the adverse effects of trucks, effects on rural character and visual amenity, and on local ecology, and traffic intensity and safety concerns.

FINDINGS LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK

One party engaged early, communicated and modified their actions based on stakeholder concerns. They succeeded in achieving substantially all their aims. One party had problems. The community were suspicious due to prior compliance breaches on another property nearby. Conflicting regulatory requirements on whether consent should be notified resulted in this firm taking the option not to notify which resulted in community resentment and distrust. The organisation experienced ongoing problems with community groups. Consent was granted in Environment court with issues remaining. The firm then experienced long and expensive delays in achieving their development aims.

We find a regulatory system where simple compliance limits stakeholder engagement by prescribing, via the consenting authority, who the stakeholders are. At the same time the system empowers others not consulted, or those in the identified group who are disaffected, to pursue their agendas irrespective of what may be seen, or has previously be determined to be, a balanced outcome for all stakeholders. This approach opens a door for NIMBYism to flourish and partisan interests to significantly impact the business needs of the smaller, less sophisticated and resourced SME. The system does not serve the SME sector well, a sector where clear rules to be followed are the expectation and meeting the explicit minimum requirements will achieve the outcome. However, we also find a system which is not flawed in its primary objective of inclusion, protection of divergent interests and need to have full control of the decision-making process of local authorities.

Roberts (Reference Roberts1992) finds stakeholders’ environmental concerns influence corporate activities. Large corporates overtly use stakeholder engagement to augment the regulatory environment by meeting the community as well as regulatory expectations. The comparison we note with the larger organisations support Roberts finding and reinforce the disparate outcomes for the SMEs who do not appear to recognise the interrelationship of the resource management legislation and stakeholder engagement.

RELEVANCE AND CONTRIBUTION

The literature is awash with the need for stakeholder engagement, including the advantages and the risks of not engaging. In relation to LULU and the three perspectives taken, we found discussion of the use of stakeholders’ engagement by larger organisations (Roberts, Reference Roberts1992), a range of strategies to engage and manage NIMBY issues, (Kaya & Erol, Reference Kaya and Erol2016), the need for an early start (Schwarz, Reference Schively2004), issues arising with stakeholder trust (Schively, Reference Scharff2007), the effect of the NIMBY on land use (Mannarini & Roccato, Reference Mannarini and Roccato2011), and the roles of flawed systems in promoting NIMBYism (Kraft & Clary, Reference Kraft and Clary1991; Groothuis & Miller, Reference Groothuis and Miller1997).

The contribution of this study is in the melding of the three perspectives within a regulatory system which is not inherently flawed, but is complex, policy based, and punitive on those who are reliant on, and expect, prescriptive and exhaustive legal mechanisms. The organisations behaviours illustrate the two extremes. One a restrictive compliance-based approach focused on meeting minimal requirements and accepting the dictated process of the consenting authority. The other recognising the wider needs of the legislation and understanding the role of the consenting authority as a part of the potential process with its evidence, assessments and decision open to continual review. This is evidenced by the history and supported by the decisions made.

Stakeholder engagement cannot be easily started within the legislative timeframe. It must be undertaken as part of a process and attitude of an organisation as an ongoing and long-term strategy. This is evidenced by the actions of Brookby Quarry. The legislative framework correlates with wider stakeholder theory and attempts to create an alignment of interests. The framework also creates an envelope which can easily be seen as a ‘complete solution’. We suggest many SMEs will not have the ability, resources or maturity to recognise the wider game and get caught in a regulatory approach which does not correlate with the actual regulatory framework.

We acknowledge this study was focused on only two organisations. Also, the motivation of the organisations suggested are inference, and the wider engagement of the one could, at least in part, be attributed to a more detailed preparation of their compliance obligations (mitigation plan). The industry chosen is rife with NIMBY issues, a magnet for conflict, a factor which drives parties to taking polar positions. There is no middle ground. A qualitative study of organisations across a wider range of industries with outcomes from failure (as defined earlier) to success and those in between is needed to understand the mechanisms to address the questions raised for the SME sector. This paper reflects the SME issues for the quarries.

CONCLUSION

This paper has used stakeholder theory and NIMBY research to contrast the resource consent applications and processes of two small firms, against the backdrop of the legislative framework.

One firm with strong stakeholder relationships was able to gain resource consent and actioned its expansion quickly. The other firm although gaining consent has met with major community challenges and 3 years on has not realised its expansion. The underlying approach of the firms is fundamentally different. One is compliance driven, the other, has developed a culture of engagement. This is evidenced by the history and supported by the decisions made. Stakeholder engagement undertaken as part of a process and attitude of a firm is an ongoing and long-term strategy. The strength of this study lies in its ability to compare two similar firms which share the same environments however the case study approach as a research method decreases the generalisability of the findings.

The stakeholder analysis undertaken by the firms appear similar in identifying stakeholders, however, the engagements undertaken are divergent. The question mark is whether the company engaged in stakeholder analysis at all, or, engaged only in a regulatory compliance strategy. Stakeholder engagement is complicated when regulatory requirements provide mandatory stakeholder interaction. This, as an observation, may lead to an adversarial view of the parties not a contributing team view. The underlying theoretical view of stakeholder engagement is that developing and maintaining relationships are desirable goals for both the stakeholder and the firm. Some regulatory regime mimics aspects of the theoretical but, may also lead to firms applying a compliance approach, which if not supported by a culture of engagement, will relegate stakeholders to a category to be managed via the process, the courts, or other adversarial negotiation. In the context of growing NIMBY behaviours, the recognition of the regulatory framework in providing both an avenue for communities to negate unwanted land use, and, as a mechanism for the organisation to control that avenue by early and wide engagement is of growing importance.

Conflicts of Interest

Lyn Murphy was an elected member of the Franklin local board, Auckland Council, at the time of the resource consent application.