Introduction

Racially disparate policing, prosecution, and punishment have direct and indirect effects on health outcomes for impacted individuals, families, and communities.1 These disparate effects may be obvious, such as in instances when lethal force is used by police or when the cumulative effect of disparities in the criminal legal system leads to the state executing someone. The person killed by police or sentenced to be executed by the state is disproportionately a Black person. Less obvious but no less important are the direct and indirect effects on health outcomes that result from non-lethal encounters Black people face in the criminal legal system due to choices reflected in legislation, policies, and practices effectuated in policing, prosecution, and punishment.

Our commentary begins by examining the institutional and structural determinants of the criminal justice system and how they are forms of social control. Driven by pragmatism and resources, researchers, advocates, and policymakers often focus on specific race inequities in policing, prosecution, defense, and sentencing. They also tend to focus on particular institutional criminal legal system actors, including police, prosecutors, defenders, and judges. The focus on addressing race inequity, though, can produce a certain myopia. For example, if relative to White people, Black people are disproportionately killed by the police or executed by the state, the solution is not for the police or the state to kill more White people. Race inequity may be reduced or eliminated, but this approach loses sight of what we ought to be focusing on, which is improving outcomes for all individuals, families, and communities. We conclude the commentary by describing how a health justice frame provides a lens to examine racial inequities in the criminal legal system that allows reforms to be tied to improving individual and community health outcomes.

Health justice broadens the criminal justice reform discussion and allows for a deeper examination of institutional, structural, and political determinants of criminalization that have a cumulative effect on modern day policing and incarceration. Within this broader frame, we highlight some of the tools used to perpetuate racial inequities within the criminal justice system, such as the criminalization of certain “illicit” drugs and the reliance upon fines and fees. The broader health justice frame is more effective in deriving strategies for reform and assessing their success, again with an eye toward improving outcomes for individuals, families, and their communities.

The United States leads the world in having the most people incarcerated as well as having the highest rate of its population incarcerated. While inequities in incarceration exist for many communities of color, in comparison to other racial and ethnic groups, Black Americans remain at the highest risk of being incarcerated.

The Criminal Legal System and Social Control

The United States leads the world in having the most people incarcerated as well as having the highest rate of its population incarcerated.2 While inequities in incarceration exist for many communities of color,Reference Mauer and Ghandnoosh3 in comparison to other racial and ethnic groups, Black Americans remain at the highest risk of being incarcerated.Reference Gramlich4 This should not come as a surprise, as the modern criminal legal system has played a long-standing critical role as a mechanism of social control of Black Americans. Formal and informal policies and policing have restricted the social and economic advancement and well-being of Black people, their families, and their communities.

Although the 13th Amendment granted freedom to formerly enslaved Black people, it included a loophole, permitting involuntary servitude as punishment for crime.5 The modern criminal legal system and the prison-industrial complex emerged to create a new form of enslavement through the convict lease system.6 Violations of the post-slavery social order were criminalized, leading to the arrest and imprisonment of many recently freed men and women. The new Black Codes criminalized such things as “vagrancy, absence from work, the possession of firearms, insulting gestures or acts, or familial neglect, reckless spending, and disorderly conduct” as well as the “failure to perform under employment contracts.”Reference Ocen7 Given severe fines and long prison sentences, Black people were then “leased” to work on plantations, resulting in convict labor replacing slave labor.8 The previous social order that controlled Black people and extracted labor through the institution of slavery has been “modernized” through a range of policing practices informed and supported by a matrix of local, county, state, and federal policies that are discussed below.

Features of the postbellum criminal legal system included disparate policing and disparate punishment, which is evidenced by the fact that Black people constituted the majority in postbellum Southern prison camps, “with their populations rising to as high as 90%.”9 This postbellum criminal legal system evolved into the modern criminal legal system and extended to all regions of the United States in federal prisons, state prisons, and private prisons.Reference Goodwin10 As discussed in the next section, Congress and several U.S. Presidents then played a key role in extending the reach of the criminal legal system by criminalizing certain narcotics, and providing a new and ultimately more powerful tool for police, prosecutors and, judges to regulate Black (and other) bodies through adjudications of guilt and punishment.

Extending Social Control by Criminalizing Certain “Illicit” Drugs

The war on drugs began with the policing of opium in California in the 1870s, through the passage of the first drug law, which was motivated by anti-Chinese sentiment and directed against Chinese immigrants.Reference Boldt11 In the early 1900s, laws were passed to criminalize cocaine, which were directed against “Negro Cocaine ‘Fiends.’”Reference Sklansky12 This was then followed by laws passed to criminalize marijuana, which was associated with Mexican immigrants.Reference Das13 In each of these instances, particular groups were presented as a threat, justifying legislative criminalization of certain illicit drugs. Though ostensibly targeting illicit drugs, the new laws created additional ways to police certain bodies of color and managed the “threat” through disparate policing, prosecution, and sentencing.14

The war on drugs became turbocharged when President Nixon announced in a press conference on June 17, 1971, that “America’s public enemy number one in the United States is drug abuse,” and that it was “necessary to wage a new, all-out offensive.”Reference Nixon15 What was unstated by Nixon but revealed years later by his domestic policy adviser, John Ehrlichman, was that the real targets were what the Nixon campaign and the Nixon White House perceived as its primary enemies, the antiwar left and black people. Ehrlichman confessed:

We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities … [and] vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.Reference Baum16

In a special message to Congress sent the same day as the press conference, Nixon requested legislation and funding to engage in this “all-out offensive.”Reference Nixon17 After the message, Congress passed legislation to support Nixon’s war on drugs.

What followed was a largely uninterrupted escalation of police and military forces to remove illicit drugs from American cities. Though Presidents Ford and Carter supported decriminalizing marijuana, President Reagan reversed course and revitalized and intensified the war on drugs.Reference Phillips18 In the fifty years since Nixon’s announcement, Congress has committed more than $1 trillion to the war on drugs, despite many failures.Reference Lee19 The failures to remove drugs or adequately control illicit drug use has expanded into abuse of legal substances (e.g. opioids) and calls from many activists to reform rehabilitation opportunities, decriminalize illicit substances, and legalize some to all drugs.Reference Lopez20

During this period, links were made between drug use, violence, and rising crime rates.Reference Baradaran21 Drug use and abuse, which could have been addressed as a public health issue, were instead addressed through the criminal legal system. In 1971, when Congress classified marijuana as a Schedule 1 drug, the most restrictive drug classification, it created the foundation for facially race-neutral laws and policies that criminal legal system actors used to target Black drug dealers and users despite evidence of no difference in Black and White drug dealing or use.Reference Spohn22

Facially race-neutral laws criminalizing opium, crack cocaine, and marijuana exacerbated disparate policing, prosecution, and punishment of Black people. Specifically, it gave police officers the legal authority to act with impunity to regulate Black people through traffic stops, stop-and-frisk, and naked violence. It gave prosecutors the legal authority to participate in regulating Black and Brown people through the discretion they exercised in charging, plea deals, and the punishment they sought. It likewise gave judges a key role in regulating Black people. All of this has produced the nightmare of racialized mass incarceration.

Beyond Incarceration: Fines and Fees as a Mechanism to Maintain Social Control

The use of racialized profiling and criminalization tactics have occurred within a broader political and social context where longstanding sociological and psychological factors play powerful, yet rarely mentioned roles. The threat of incarceration and incarceration itself are the most apparent ways that the criminal legal system is deployed as a form of social control. Less apparent is the use of fines and fees imposed upon those entangled in the criminal legal system that produces, in some instances, a modern form of debt peonage.Reference Hampson23 These fines and fees also leave individuals and families saddled with debt that hinders their ability to escape further entanglement with the criminal legal system.Reference Birckhead24

The 1980s, re-introduced state and local government use of fines and fees to fill budget gaps. These processes accelerated in 2008, during the recession, despite declining rates of crime in the United States since the 1990s. Violent crime rates fell 51% between 1993 and 2018, while the property crime rate decreased 54% during the same time frame.Reference Maruschak and Minton25 Despite this decline in property and violent crime, the United States still has the highest incarceration rate in the world. In fact, the passage of the 1994 Crime Bill created opportunities to increase the number of police officers, new policing strategies, and use of force techniques, which includes stop-and-frisk and no-knock warrants.

Reducing crime was coupled with an expansion of the penal system and assessment of court fines and probation fees for those who enter the criminal legal system. These fines have led to debtor’s prisons and cycles of imprisonment for those who cannot afford to pay these fines and fees.26 Historically, the assessment of fines and fees as well as parole and probation were used as less punitive measures than jail and provided restoration for those recently incarcerated. However, over time the parole and probation process have become costly to individuals released from imprisonment and their families, while also creating administrative challenges to managing caseloads, increasing costs to taxpayers, and becoming a primary driver for incarceration.

Furthermore, although the rate of incarceration has declined, spending on jails continues, which is often supported by the assessment of fines and fees. Following national trends, the rate of incarceration for communities of color declined by 28% for Black Americans, 21% for Hispanic residents, and 13% for White populations. Data documenting this decline only includes those incarcerated in federal prisons, excluding those in local or county jails.Reference Carson27 Despite the changes in crime and the number of incarcerated adults, the cost of operating prisons and jails has increased since 2007.28 Spending for jails has increased by 13% between 2007 and 2017, reaching $25 billion.29 This increase in spending has occurred although jail admissions dropped by 19% during this same time period. This imbalance of reductions in the number of incarcerated individuals and increased spending, which is subsidizes by fines and fees, is evidence of the institutional determinant of the criminal justice system.

Criminalization Leads to Disparate Policing, Prosecution, Incarceration, and Fines and Fees and Has Community and Health Spill-over Effects

There is a clear association between hyper-policing and poor community health outcomes.Reference Sewell30 Associations that have been derived between segregation, race/ethnicity, and/or income at neighborhood levels continue to provide evidence as to why these neighborhoods are both hyper-policed and experience disparate health outcomes.Reference Feldman, Gruskin, Coull and Krieger31 There are links to both physical and psychological violence when police utilize stop and frisk to look for drugs or other contraband.Reference Cooper32 Recent studies show an association between important health behaviors and police encounters that are important to managing health on a daily basis, such as cigarette smoking and engaging in physical activity.Reference Sewell, Feldman, Ray, Gilbert, Jefferson and Lee33 In the public health literature, these behaviors are directly linked to risk factors for chronic diseases, such as obesity and to the onset and proliferation of chronic conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer.Reference Kwate and Threadcraft34 The racial composition of neighborhoods contributes to both physical and mental health risks.Reference Gilbert and Ray35

There are psychological risk factors that structure health behavior decision-making that differs for Black men and women based on the racial composition of the neighborhood.36 Fear of being chased by police while running is a major concern for Black men when being physically active in a predominantly Black neighborhood. In these same neighborhoods, Black women have higher rates of chronic diseases that are connected to social and economic stressors when Black men are harassed, injured, or killed by police. This evidence highlights not only hyper-policing’s effects on health, but how it may structure health outcomes for Black men and women differently, suggesting behavior and policy interventions have to take a health justice frame to ensure equity can be achieved for both groups.

Neighborhood characteristics structure police activity, as evidenced by the use of criminal justice models that have been dominated by metaphors of “broken windows” and have focused on perceived community decline as an ecological determinant of crime. The idea is that a community in decline lacks social order and control and is fertile ground for crime.Reference Kondo37 These models suggest cultural deficits and do not reflect systemic policy efforts that contributed to structural decline in these neighborhoods. Residential segregation in the United States, one example of systemic policy efforts, peaked around 1960-1970, but declines have been slow, especially from 1980-2010. However, Black individuals continue to be the most residentially segregated racial group with average neighborhood racial composition rates in 2010, similar to those in 1940. Racially segregated neighborhoods that are predominately filled with Black individuals tend to lack economic investment, and thus are economically depressed.

It is easy to characterize an economically depressed area by sight based on a high concentration of poor housing stock, such as a large number of vacant lots, abandoned buildings, and crumbling houses.Reference Gilbert and Goodman38 Other features of these neighborhoods include exposures to environmental toxins such as being in close proximity to highways, bus depots, and superfund sites with contaminated soil and water.Reference Campbell, Caldwell, Hopkins, Heaney, Wing, Wilson, O’Shea and Yeatts39 Bodies of research across disciplines show that the cumulative risk of being hyper-policed and increased health risks that stem from policies around policing, result in systemic community disinvestment. The totality of these risks at individual, family, and community levels, limits economic growth and health promoting resources.Reference Tsai, Mendenhall, Trostle and Kawachi40

Using a Health Justice Frame to Formulate Strategies for Criminal Justice and Police Reform

Understanding the institutional and structural determinants of the criminal justice system become important to framing the broader context of each contributing factor perpetuating racial inequity within the criminal justice system. These determinants have contributed to negative behaviors within various segments of the criminal justice system such as:

-

• Reliance of state and local courts, jails, and prisons on fines and fees to provide revenue;

-

• Racial profiling and bias in policing;

-

• Discretionary actions from prosecutors that results in inequitable sentencing; and

-

• Inability of those formerly incarcerated to access support services, health care services, and housing subsidies, which compounds their financial burden, when fines and fees remain part of their financial responsibilities.

Health justice offers an exciting, innovative framework for not only re-examining these institutional and structural determinants of the criminal justice system, but also imagining an integrated approach to achieving equitable outcomes.Reference Wiley41

This health justice frame helps to break down the silos between different areas of knowledge and advocacy so that instead of examining social inequities in health OR housing OR income and wealth OR criminal justice, the connections between different areas are explored because they are interrelated. Thus, in order to be effective, any efforts at reform should adopt a health justice frame to understand and appreciate these connections. Too often, legal reform is circumscribed by artificial legal doctrinal boundaries. The criminal legal system presents a fruitful area to apply a health justice frame. Health justice, which centers the needs of the community and supports collective reform, offers a different way to see problems produced by the criminal legal system as well as to imagine different solutions that are tied to individual and community health outcomes.

For example, one could look at the criminal legal system in Washington state, which in 1980, had the highest Black-White disproportionality in incarceration in the country. This disproportionality ratio dropped from 14.1 in 1980 to 6.4 in 2005.42 Though this may look like progress, the reduction in the disproportionality ratio from 1980 to 2005, resulted because the White incarceration rate quadrupled (from 95 to 393 White people incarcerated per 100,000 White Washington residents) while the Black incarceration rate merely doubled (from 1,342 to 2,522 Black people incarcerated per 100,000 Black Washington residents).43 A myopic focus on race disproportionality can obscure what a health justice frame sees clearly, that the doubling of the Black incarceration rate in that timeframe still inflicts serious harm to individual and community health. The health justice frame allows us to reimagine “safety and security” policing and to imagine public health interventions instead of the usual “law and order” response of heightened policing, prosecution, and incarceration.Reference Pamukcu and Harris44 In applying this health justice frame, it is critical to embrace race-consciousness, especially as it relates to the criminal legal system with its long-standing role in subjugating Black people.

Those seeking to reduce racial inequities in the criminal legal system will often focus on a particular goal, such as decreasing lethal police encounters. For example, if the diagnosis is that a significant percentage of lethal police encounters involve a person undergoing a mental health crisis, proposed interventions may focus on altering the personnel who respond to these situations and/or by altering how personnel respond in these situations. If the diagnosis is that a significant percentage of lethal police encounters result from police escalating the use of force, then proposed interventions may focus on de-escalation. Though these interventions could be race-neutral, we suggest that these interventions be race-conscious, which aligns with existing evidence of the systematic differential police encounters with Black people. Race-conscious interventions would help reduce racial inequities in policing by ensuring that Black and Brown people who are disproportionately targeted are consciously protected. Relatedly, interventions that reduce overall disproportionate minority contact (DMC) with police will likely yield dividends with regard to all uses of force, including lethal encounters.

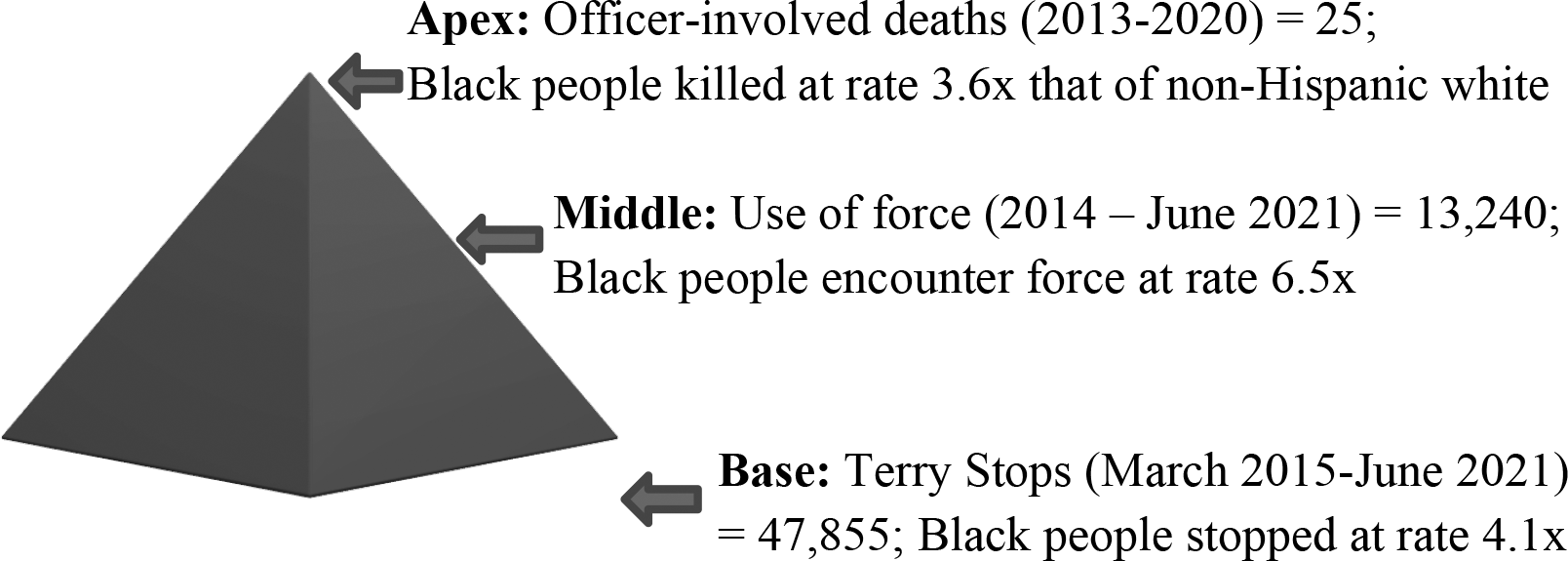

A recent report on race and Washington’s criminal justice system documented DMC in police encounters for several jurisdictions, including the City of Seattle.45 The statistics for the Seattle Police Department show consistent race disproportionality with regard to officer-involved deaths, overall use of force, and investigative Terry stops. Though the time periods comparing different levels of force applied in the figure below are not in perfect alignment, they allow for comparison based on relative rates over several year periods.46

Figure 1

If the goal is to reduce DMC, it is critical to know at what points during a police encounter DMC occurs in order to identify possible causes and possible interventions for each type of police encounter. But the report suggested that racial inequities in lethal police encounters could be reduced simply by reducing overall DMC with police. A working hypothesis is that fewer police encounters will likely lead to fewer “opportunities” for police to escalate the use of force.47 Stated differently, DMC might be reduced at higher levels of the pyramid if the base of the pyramid were reduced.

Though the goal of reducing DMC in lethal police encounters, itself, would justify changes in policies and practices, additional justification comes from a health justice frame. Health justice recognizes the broader harms caused by DMC in police encounters that are inextricably tied to the historical and present-day use of the criminal legal system as a racially discriminatory mechanism of social control. This health justice frame suggests that reform requires that the criminal legal system be reduced.

Shrinking the criminal legal system will help to: (1) address systemic racism that leads to police killings; (2) re-direct resources towards public health prevention strategies that can support reductions in social and structural determinants of health that lead to health inequities; and (3) reduce the burden of officers’ involvement in collecting revenue for municipalities’ general funds, which have become the primary strategies supporting detaining and arresting Black people through stop and frisk practices and other forms of hyper-surveillance. An inconvenient truth is that our overly bloated criminal legal system depends on racially disparate policing, prosecution, and incarceration. And, to add insult to injury, the imposition of fines and fees means that Black people pay for the privilege of having their communities over- and under-policed.

There is a growing list of court activity produced by the Fines and Fees Justice Center to reduce or eliminate the disproportionate effect of fines and fees on communities across the United States.48 There have been several case studies on fines and fees, including one in Indiana that showed how unpaid fines and fees were converted into civil judgments, which were used to obtain real estate liens.49 This action was challenged in Timbs v. Indiana, and the Supreme Court50 ruled that local governments should be banned from collecting excessive fines, such as the seizure of property, which individuals cannot afford.51

Additionally, there are over 20 states engaged in some form of bail and pre-trial reforms and close to 30 states applying a fines and fee tool to make policy changes.52 Examples include enacting and implementing alternatives to arrest, incarceration, and supervision. These reforms can divert low-risk individuals to social or health services instead of arrest and helps to prioritize higher-risk individuals for the court system.53 These recommendations seek to advance standard definitions of technical violations (of parole and probation), minimize arrests for these violations, and maintain continuity of care and access to social and health services.54

The health justice frame can be used to mobilize individuals, groups, and communities within the United States to enact anti-racist policies and re-structure resources within communities of color and low-income communities. The frame can be used to expand the #defundthepolice movement that highlights the current United States criminal justice system’s role in undermining social relationships, which has disrupted families, caused irreparable harm, and utilized police as a mechanism for controlling Black communities and constraining their social mobility.

Several Presidential administrations have aimed to curb incarceration rates with sentencing reform in 2018, bail reforms dating back to 1966, and pretrial reforms in 1984. These efforts have been siloed and unable to remedy the centuries-long interconnected web of policing; courts, fees, fines; and local, county, state, and federal policies that have continued to incarcerate many Americans, with an overrepresentation of Black citizens and low-income citizens in jails and prisons. In this commentary, we have emphasized that criminal justice reform must include a health justice frame. Efforts to address the bloated criminal legal system can only reverse mass incarceration when they are accompanied by structural change to the entire system. Diverting resources to address the institutional and structural determinants of the criminal justice system, which have been used as a form of social control, can fundamentally improve social and health issues at individual, family, and community levels. A health justice frame ensures that criminal legal system reforms are tied to health equity, especially for those individuals, families, and communities that have previously been denied justice.

Acknowledgements

We thank the editors for inviting us to contribute this commentary to this Health Justice Symposium issue. We also thank Raechel Fraser, Amanda Lee, and Nicole Rudnicki for their research assistance.

Note

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.