Over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic from 2020-2021, scarcities have emerged as a unifying threat to the public’s health. Scarcities of tests, protective equipment, masks, hospital beds, ventilators, medical personnel, and vaccinations have all contributed significantly to excess morbidity and mortality.Reference Rossen, Branum, Ahmad, Sutton and Anderson 1

Deleterious impacts of scarcities tied to the pandemic extend well beyond medical settings. Tens of millions of Americans have lost their jobs, business interests, health insurance, financial support, and livelihoods. 2 Resulting poverty coupled with homelessness and other spiral-ing, economic trends have found millions of persons experiencing limited or uncertain access to food.Reference Wolfson and Leung 3 At the initial height of the pandemic in late April 2020, greater than 50 million Americans were food insecure, many for the first time. 4 More than 20% of all U.S. households reported insufficient resources to buy food.Reference Bauer 5

Significant physical and mental health outcomes extend across affected populations. 6 As households stretch budgets to provide basic food needs, failures to assure other necessities (e.g., medications, safe childcare, stable housing) exacerbate public health impacts.Reference Murthy 7 Older adults with chronic health conditions (e.g., diabetes, heart disease) experience heightened health risks when specific nutritional needs are unmet.Reference Wolfson and Leung 8 Food insecure children face higher rates of hospitalizations, behavioral issues, and developmental impairments.Reference Goger 9

Immediate assistance to remedy food scarcities arose through multiple public and private sector sources, 10 including laudable efforts from America’s network of food banks/ pantries (FBPs). In response to significant spikes in demand and diminishing supplies,Reference Friedersdor 11 many FBPs resorted to “first-come, first-served” distribution strategies. Though efficient in serving long lines of recipients in vehicles or on foot, hundreds of thousands of Americans were turned away or otherwise lacked access to FBP resources for multifarious reasons. Escalating cases of COVID-19 in 2021 prolong food distribution challenges.

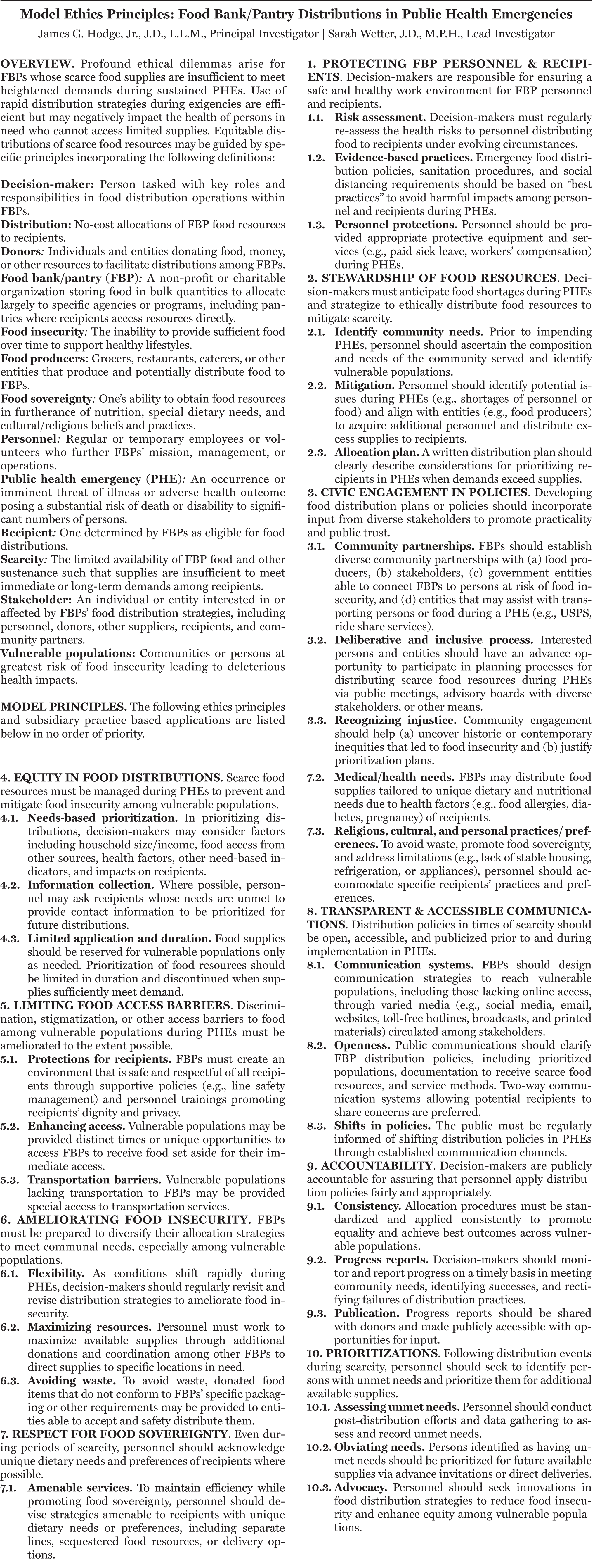

Profound and unique ethical implications underlie FBPs’ emergency distributions impacting the health of at-risk Americans. As presented in Figure 1 and elucidated below, consideration and utilization of a model series of ethical principles guiding FBP distributions may help assure greater access to essential food and sustenance among vulnerable populations during public health emergencies (PHEs).

Figure 1

Food Demands and Distributions During COVID-19

Americans’ demand for food assistance rose at an extraordinary rate during the COVID-19 pandemic.Reference Kulish 12 Despite infusions of federal and state emergency funds supporting multiple food access programs (e.g., SNAP benefits, school lunches) Americans’ needs were insatiable.Reference Wetter, Hodge, Carey and White 13 Unprecedented levels of hunger presented unique challenges for FBPs faced with depleted supplies, receding volunteers, and extensive public health infection control requirements during the pandemic. Feeding America, the nation’s largest network of food banks, reported in November 2020 that over 80% of FBPs across the country were serving more people than they did a year ago, yielding a 50% increase in food distributed nationally.Reference Morello 14

Profound and unique ethical implications underlie FBPs’ emergency distributions impacting the health of at-risk Americans. As presented in Figure 1 and elucidated below, consideration and utilization of a model series of ethical principles guiding FBP distributions may help assure greater access to essential food and sustenance among vulnerable populations during public health emergencies (PHEs).

Spikes in demand were compounded by supply-side limitations. FBPs experienced significant supply shortages. Private sector grocers, normally a reliable source for substantial inventories among FBPs, donated fewer food items as consumers depleted their shelves. 15 Direct food acquisition costs from manufacturers increased substantially for FBPs as well, lending to a national supply gap of 10 billion pounds of food estimated across FBPs between September 2020 to June 2021. 16 Whenever FBP supplies cannot meet demand, some persons seeking emergency food resources may leave empty-handed. Recognizing the exigencies, FBPs adjusted their normal practices and modified distribution strategies to rapidly distribute food to as many persons as possible.Reference Winkie 17 In lieu of usual on site, grocery-store style services, many pantries hosted mobile food pantry events to bring goods directly to consumers. 18 Pre-pandemic eligibility requirements, typically used to vet need-based recipients, were eased or waived.Reference Smith 19

Many FBPs also began distributing food via pre-determined drive through sites (e.g., fairgrounds, stadiums, parking lots) allowing contactless service consistent with social distancing requirements.Reference Morello 20 Persons with means of transportation arrived early to receive pre-assembled boxes of food placed in their vehicles. In places like San Antonio in April 2020, persons waited for hours in lines over 6 miles long and 10,000 cars deep.Reference Lakhani, Singh and Salam 21 Those first in line were first to receive food.Reference Mehta and Chang 22 In some case, FBPs rationed supplies further by limiting the number of food boxes distributed per vehicle, even if a vehicle contained members of several families.Reference Carlson 23

Food Access Barriers and Ethical Conundrums

Access limitations and other challenges related to FBPs use of rapid food distribution approaches during the pandemic profoundly affected at-risk individuals and families seeking assistance. Hundreds of thousands of Americans “lost out” either because (1) they were at the end of the line when supplies ran dry; (2) distinct access barriers kept them from lining up at all; or (3) the supplies they received were insufficient in providing sustenance.

FBPs across multiple states (e.g., California, Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas) reported turning people away in the Spring 2020 due to insufficient food supplies.Reference Wetter and Hodge 24 Many in-need of food were unable to travel to FBPs or wait in lines due to their health (e.g., seniors, disabled persons), care-taking needs (e.g., mothers with infants), or transportation barriers (e.g., homeless persons). Fear of stigma or discrimination, especially among immigrant populations, posed additional barriers. Rumors of federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) raids thwarted undocumented immigrants from seeking food assistance in Texas even prior to the pandemic.Reference Wilson 25 Others arriving at FBP drive throughs did not acquire foods necessary to fulfill their health needs (e.g., persons with diabetes, allergies, or who are pregnant), or aligned with their cultural/ religious practices due to FBP limitations on pre-boxed food selections.Reference Flores 26

Persons at highest risk of food insecurity and related health consequences likely faced the greatest hurdles to accessing FBP resources, lending to significant disparities. Similar issues underscore the development of ethical plans for distributing other scarce resources, such as medical supplies, services, 27 and vaccines during PHEs.Reference Toner, Barnill and Krubiner 28 Ethical allocations of these limited resources during the pandemic accommodate populations most in-need and likely to benefit. As an essential resource for health and well-being, food distributions during periods of scarcity in PHEs should ensure vulnerable populations are not further disadvantaged.

Ethical Norms Underlying the Distribution of Scarce Food Resources

Specific ethics principles may help guide FBPs’ distribution of limited food resources to quell rates of food insecurity in emergencies. With contributions from our project advisory group, we developed a series of Model Ethics Principles: Food Bank/Pantry Distributions in Public Health Emergencies (“Model Principles”) (see Figure 1). These principles were derived from initial research and applications focused on prevailing ethics approaches to emergency distributions of scarce health/medical resources (e.g. ventilators, ICU beds, vaccines). From these analyses arose multiple precepts with input from experts in health and food/nutrition policy, emergency preparedness, FBP operations, and ethics.

The resulting Model Principles set forth core ethics statements (e.g., 1, 2, 3) underlying the distribution of scarce food resources supplemented by correlated, practical guidance (e.g., 1.1, 1.2, 1.3) for their implementation. The principles are not intended to create legal standards or set affirmative duties or obligations. Rather they guide FBP decision-makers and personnel at all levels toward more equitable food distribution policies and practices during periods of scarcity in PHEs.

Acknowledging the complex, laudable objectives of FBPs seeking to mete out food supplies in exigencies, the Model Principles proffer alternatives to typical distribution strategies that can unfairly disadvantage vulnerable populations facing barriers to accessing limited FBP resources. Assuring the health and safety of all persons involved in distributions, including FBP staff, volunteers, and recipients, is preeminent (Principle 1). FBP decision-makers must create a safe and healthy environment at distribution sites and ameliorate diverse risks ranging from infection spread to stigma and discrimination. This includes implementing evidence-based practices and protections for FBP personnel and recipients through line safety management (Principle 1) and personnel trainings on anti-discrimination and anti-stig-matization (Principle 5).

Advance planning and stewardship of food resources (Principles 2, 3) facilitate expedited, flexible distributions amid changing environments. Mechanisms for building public trust interwoven in the Model Principles strike an intricate balance between promoting individuals’ needs for adequate food and FBP efficiencies in serving the greatest number of persons. Data collection and record keeping enable FBPs to calculate and better predict recipients’ demands and promote public accountability through dissemination of progress reports and opportunities for stakeholder input (Principles 9, 10).

Equitable allocation of FBP resources during scarcity is also key (Principles 4, 5). Needs-based prioritization schemes should promote equity and social justice by serving populations at heightened risk of food insecurity and those facing specific food access barriers such as lack of transportation. Use of pre-packaged food boxes may be efficient during periods of scarcity, but individuals’ dietary needs and cultural/religious preferences should also be respected where possible (Principle 7).

Serving the greatest numbers of persons possible in emergencies entails identification, communication, and prioritization of vulnerable populations for FBP distributions (Principle 10). FBP partners and other stakeholders should devise distribution policies and communicate them transparently leading up to and during periods of food scarcity. Communication systems should include alternatives to reach at-risk individuals, including those lacking regular access to electronic media (Principle 8).

Active engagement in diverse community partnerships allows FBPs to connect with additional persons or supplies that can help obviate shortages (Principle 3). While decision-makers are accountable to donors and recipients to implement distribution policies fairly (Principle 9), they must also adapt to shifting circumstances through diverse distribution strategies that maximize resources and avoid waste (Principle 6). Following food distribution events where supplies are insufficient to meet community needs, for example, FBPs should identify and advocate for underserved persons, prioritizing them for future distributions (Principle 10).

Collectively the Model Principles are crafted to guide emergency distributions of scarce food resources through FBPs to assure equitable allocations and limit deleterious impacts specifically among vulnerable populations. How these principles are operationalized in the field among FBPs may vary significantly depending on (a) existing policies and available resources, (b) extent, type, and duration of the emergency, (c) size of the community, and (d) scope of needs experienced among community members. Irrespective of the unique settings or invocations of these principles, the goal remains the same: assuring equitable access on expedited bases to as many food insecure Americans as possible to limit or prevent correlated public health harms.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research and findings was provided through a Presidential Award grant dated September 9, 2020 from The Greenwall Foundation, New York, NY, to the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law, ASU. The authors thank the members of the project advisory group for their input and guidance: Leila Barraza, J.D., M.P.H.; Ruth Gaare Bernheim, J.D., M.P.H.; Ruth Faden, Ph.D., M.P.H.; Lance Gable, J.D., M.P.H.; Amanda Karls, J.D.; Jill Mahoney, J.D., M.P.H.; Michael McDonald, M.I.B.; Stephanie Morain, Ph.D., M.P.H.; Daniel Orens-tein, J.D., M.P.H.; Jennifer Piatt, J.D.; Anne Readhimer, M.S.; Sarah Roache, L.L.M., L.L.B.; Lainie Rutkow, J.D., Ph.D.; Sallie Thieme Sanford, J.D.; Kristopher Tazelaar; Carrie Waggoner, J.D.; Erica White; and Lawanda Williams, M.P.H., L.C.S.W.-C.