Introduction

While it is dangerous to speak of historical constants, Western anxieties about feigned illness occur repeatedly in a variety of historical contexts. In The Odyssey, Odysseus feigns madness by sowing salt in a field. In the Hebrew Bible, when David fled from King Saul, Bathsheba reported that he was sick in bed and could therefore not attend.

13th century physician, alchemist, and astrologer Arnau de Vilanova was anxious about “patients intending deception through faked illness or supplying wrong or outdated urine.”Reference Lynn 1 In part, Arnau’s anxiety arose because patients sometimes sought to test the expertise of physicians by sending

an intermediary with ‘their’ urine in their stead, making it impossible for the doctor to see and assess the patient directly through other visible symptoms. Presented with a flask of mysterious liquid and the poker face of a healthy comrade of the ill, the physician was at risk of discrediting himself spectacularly. 2

In his writings on uroscopy, Arnau therefore prescribed at least nineteen pieces of advice by which the keen physician could separate the truly ill from the tricksters. For example, he suggested that physicians “ask leading questions in the hope the uneducated client would accidentally reveal the real source of the liquid.” 3

In Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde (c. 1380s) Troilus feigns a fever to take to his bed and therein hide his love for Criseyde from the public world.Reference Muscatine 4 In 15th century Valencia, court records regarding disputes between buyers and sellers of slaves show that slaves were routinely accused of feigning illness. Slaveowners did so “in order to sabotage their resale, thereby preventing their transfer to an unknown, and potentially worse, master.”Reference Blumenthal 5 Four centuries later, slaves in the 19th c. US were also often accused of “malingering” or feigning illness.Reference Boster and Fett 6

In the early modern context, feigned illness is an important motif in Shakespeare’s works, including in the character of Hamlet himself, Prince Edgar (King Lear), and the Earl of Northumberland (2 Henry IV).Reference Hackford 7 While the reasons for anxieties about feigned illness vary, astonishingly often they have centered on pain. In Papal physician Paolo Zacchia’s early modern medico-legal text Quaestiones (1661), evidence of pain is often the central bone of contention.Reference De Renzi 8 In examining the case of a painful malady involving Spanish priest Christophorus Gomez, Zacchia paid special attention to the problem of malingering or feigned illness. He devoted an entire section of the text

to the simulation of diseases and was here reporting the received view that fear, shame or greed were the main causes of this phenomenon … Malingering had traditionally been associated with avoiding tasks and assignments, but reasons to simulate illnesses or unusual alterations of the body were allegedly on the increase in early modern society. 9

Thus, Zacchia documented a variety of social contexts in which fears of malingering might arise, including

-

The “armies of undeserving poor who would routinely fake fits to stir the charities of passers-by;”

-

“impudent women simulating ecstasy to gain status in their communities;” and

-

“defendants who would pretend to suffer from all sorts of illnesses to avoid the torture that was routinely administered in Continental tribunals.” 10

Surely, Zacchia observed, it is conceivable that a timorous priest might exaggerate a “minor ailment to make his workload lighter.” 11 But the patient himself was deemed untrustworthy, and so “his testimony had to be corroborated by other evidence.” 12

There are two takeaway points here. First, anxieties about malingering or feigned illness are at least a thousand years old in the West. Second, doubt is a core aspect of how pain in particular has been socialized in the West for roughly the same length of time. This astonishing persistence of doubt has rarely been distributed equally, however. Women, slaves, soldiers, and, especially since the early modern era, Black and Brown peoples in particular seem more likely to excite doubt and accusations of feigned illness.

There are two takeaway points here. First, anxieties about malingering or feigned illness are at least a thousand years old in the West. Second, doubt is a core aspect of how pain in particular has been socialized in the West for roughly the same length of time. This astonishing persistence of doubt has rarely been distributed equally, however. Women, slaves, soldiers, and, especially since the early modern era, Black and Brown peoples in particular seem more likely to excite doubt and accusations of feigned illness.

These anxieties about malingering have not escaped contemporary scholarly attention. However, there exists no single synthetic historiography explicating the persistence of doubts and anxieties about feigned illness in the West. This gap is especially significant given the primary claim of this essay: concerns of malingering or feigned illness are fundamental to USian social welfare policy. It is thus not simply that accusations of malingering are important in health care encounters; rather, what passes for a contemporary welfare and social policy regime in the US is deeply linked with concerns about people feigning illness.

Admittedly, there is a sense in which this too is not novel. Distinguishing between the deserving and undeserving poor has been a core feature of welfare policy in the West since at least as far back as the Elizabethan poor laws of the early 17th c.Reference Hindle, Doran and Jones 13 As noted above, di Renzi demonstrates that by the 1660s the perceived need to make such a distinction was firmly entrenched. Despite these general connections between concerns of deservingness and social welfare policy in the West, few sustained studies have explored potential links between accusations of malingering in particular and the specific scope and contours of USian social policy. This essay suggests some reasons for thinking that these links exist and merit scholarly attention and resources.

Malingering, Soldiers, and Pensions

In a 1998 essay on malingering in the modern era (roughly post-1800), historian of medicine Roger Cooter explained that accusations of feigned illness took on particular force in martial contexts.Reference Cooter, Cooter, Harrison and Sturdy 14 There is no question that this observation holds for US history, as we can locate anxieties about what Doron Dorfman analyzes as “the disability con”Reference Dorfman 15 as far back as pensions go in the US. For example, in prefacing William Henry Glasson’s 1918 history of federal military pensions, his editor, David Kinley, lamented that “[a]s is usual under all governments when money is to be paid out to numerous individuals in the community, a class of people fastened themselves as parasites on the beneficiaries.”Reference Glasson 16 An 1818 act of Congress established new pensions for veterans from both the War of Independence and from the War of 1812, and led to “flagrant abuses … made the subject of severe comment in the newspapers of the time. Men of means were charged with having made themselves out to be paupers in order to receive the benefits of the law … The country at large was indignant …” 17

Both Confederate and Union sources voiced considerable concern over malingering as the US Civil War dragged on, with medical men on both sides writing treatises and manuals addressing malingering and how to detect it. Confederate surgeon J. Julian Chisholm’s 1864 A Manual of Military Surgery devoted an entire section to malingering, noting that it “has ever been, and will continue to be, popular with soldiers, irrespective of the material of which an army is composed.”Reference Chisholm 18 Like Zacchia, Chisholm saw pain as a particular problem, numbering it first among “the diseases most readily and easily feigned ….” 19 “When pain is feigned, as this may really exist as a disease without external manifestation, it is the most difficult of all symptoms to detect.” 20 And like Arnau de Vilanova, he expounded on a variety of creative methods for outing the malingerer.

On the Union side, physicians William W. Keen and Silas Weir Mitchell joined George Morehouse to pen an influential 1864 article in the American Journal of Medical Sciences entitled “On Malingering, Especially In Regard to Simulation of Disease in the Nervous System.”Reference Keen, Weir Mitchell and Morehouse 21 (Keen and Mitchell would go on to help found the specialty of neurology in the US). Union surgeon Roberts Bartholow matched his Confederate counterpart Chisholm’s interest in malingering with the publication of his own 1863 treatise, this one specifically focused on malingering: A Manual of Instructions for Enlisting and Discharging Soldiers: With Special Reference to the Medical Examination of Recruits, and the Detection of Disqualifying and Feigned Diseases. Reference Bartholow 22 And like Chisholm, Bartholow perseverates on the problem of pain, noting that “[p]ain of all descriptions, existing often without evident external sign, is peculiarly liable to be simulated, because difficult of recognition.” 23 He also goes through several different techniques for testing the pain sufferer in an effort to detect malingering.

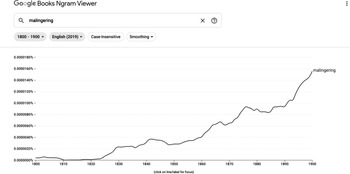

Figure 1

Ultimately, there is little question that anxieties about malingering rise in the US over the long 19th century. N-grams show a consistent rise in the use of the term beginning in the early 1820s. Not only does the absolute concern with malingering increase, but its relative distribution also begins to shift from soldiers to Black communities, and especially slaves.Reference Goldberg 24

Yet, as the 19th century lengthens, concerns over malingering also track to bourgeoisie white bodies. 25 In sum, there is a general expansion in fears of malingering from the martial contexts where it was most active, to Black bodies, and subsequently to civilian white bodies as well. Concerns over malingering in context of US veterans’ pensions antedate the US Civil War by at least a half-century, but take on a new intensity in the postbellum pension context. This is true both for the much larger and more enduring federal pension scheme for Union veterans as well as the incipient pension programs for Confederate veterans. These latter programs emphasized deservingness and merit as part of the Lost Cause mythos, with a particular emphasis on Confederate veterans who could demonstrate visible marks of their sacrifice via amputations or other highly noticeable injuries and wounds.Reference Mary-Grant 26 (In the absence of these kinds of somatic testimonies, complaints of pain tended to fare less well in justifying pension entitlements).Reference Goldberg 27

While visible injuries and disfigurements marked the Civil War veteran as authentically ill or injured and therefore deserving of public assistance, the insufficiency of welfare policy in the latter half of the 19th c. introduced a visible blemish onto the USian cityscape: Impoverished, injured, and disabled Civil War veterans begging on urban streets. Municipalities all over the US introduced so-called “ugly laws” intended to reduce the visibility of these veterans and essentially erase them from public view.Reference Schweik 28 Ironically, the structural deficiencies of US social welfare policy rendered the very markers of these veterans’ merit unacceptable for public consumption and thereby transformed the markers into stigmata.

The resonance of concerns about feigned illness, and about separating deserving from undeserving veterans in pension contexts is incredibly important because these pension schemes form the core of the modern welfare state in the U.S. Theda Skocpol’s pioneering work demonstrates how a “maternalist” welfare state began to form as both the federal government and over forty states enacted a variety of pension and welfare programs to assist spouses and children of Civil War veterans.Reference Skocpol 29 While these policies did not ultimately generate a robust social welfare program for all residents and citizens, the fact remains that what passes for social welfare policy at all in the US is historically grounded in concerns and specific programs for veterans. Therefore, inasmuch as anxieties about deservingness form a core part of the pension schemes for US veterans, it would be surprising if anxieties about feigned illness were not integrated into social policy in the US in general.Reference Linker 30

Lost limbs, amputations, and traumatic injuries play a significant role in shaping discourse on social policy and deservingness in the 19th century. Curiously, these conditions do not simply apply to pensions, but to a different social context that is also crucial for exploring the links between malingering and social policy: railways.

Railways, Injury, and Malingering

The significance of the railroads in the history of USian medicine and public health can barely be overstated. For example, with the important exception of professional sports leagues (see Stephen Casper and Kathleen Bachynski’s contributions to this Symposium), while much private health insurance in the US is obtained through employment, large employers as a rule do not directly employ health care workers to provide care for their employees. Instead, employers typically contract out with third-party administrators to arrange and manage the health care needs of their employees. This arrangement is traceable to the railway industry, which helped originate the provision of health care services for employees through a model of direct care that its employees almost universally loathed.Reference Starr 31 Employees hated the direct care model so much — largely for the conflicts of interest it structured among company physicians — that large employers distanced themselves from such a model in the first quarter of the 20th c.

The point is that important features of USian health and social policy are connected to the railway industry. And the railway industry was supremely concerned with malingering and feigned illness. Trains are mighty machines, moving immense weight at incredible speeds. Railways were — and remain — hazardous, both to workers and to passengers. The spate of railway injuries contributed to a sharp rise in tort litigation in the late 19th-early 20th centuries, which had an increasing impact on industrial revenues.Reference De Ville 32 Partly as a way of managing these liabilities, railway companies began to hire physicians both to provide care for injured employees and passengers and to prepare expert defenses against any ensuing tort litigation. The rise of railway medicine and railway surgery as distinct specialties in allopathic medicine are therefore marked by special care and attention to malingering.

To give just a few choice examples, railway surgeon Shobal Vail Clevenger remarked in an 1889 treatise that “rheumatism, fright, old age, and phthisis are frequently suggested as the real causes of death, and recovery was good ground to suspect malingering. Fraud abounded in most of the claims made. It would be interesting to be able to examine the records of the plaintiffs’ lawyers in these cases.”Reference Clevenger 33

Railway physicians and specialists in nervous injury and disease wrote of so-called “litigation” or “traumatic” neuroses, which conveniently disappeared once a legal settlement was reached or the litigation completed. Railway physicians also took special interest in spinal or other “nervous” injuries that attended the violent and relatively frequent collisions. Like their US Civil War predecessors, they deemed such injuries particularly susceptible to dissimulation; railway surgeon Webb Kelly famously remarked in the pages of JAMA in 1895 that “[r]ailway surgery without the spinal malinger would be like a ship in mid-ocean bereft of her sails and rudder.”Reference Kelly 34

I have discussed elsewhere some of the social, political, and intellectual contexts for the 19th and early 20th century rise in anxieties about malingering.Reference Goldberg 35 The focus here is on the primary role such anxieties played in the formation of modern social welfare policy in the US. Five centuries of Western social policy have centered the question of desert, of distinguishing who deserves the aid of the state and who does not. And finding those who “deserve” welfare has been central to US social policy in pension schemes and in public health litigation involving railway injuries.

Although neither of these policy interventions initiated a robust set of welfare entitlements for USians of all races, classes, and genders, the focus on deservingness and merit is not difficult to see in other arenas of social policy. US almshouses, for example, took their cue from analogous programs in 19th c. Great Britain.Reference Hamlin 36 “The poor would receive care if they agreed to reform their characters. Euro-American benevolence aimed to socialize the ‘deviant’ … as part of a moral obligation of ‘doing good.’”Reference Wagner 37 Distinguishing between the deserving poor and the undeserving “morally deviant” was critical. 38 In US and British contexts, the objective was to render living or sheltering in an almshouse so terrible that only a person or family with literally no other options would choose to do so. Only the truly desperate and optionless merited an entitlement to this most meager of benefits. Thus, David Wagner explains that US poorhouses were meant to provide poor people with “a bare minimum existence … such that they would not starve … but the subsistence was to be ‘minimal’ and harsh enough to deter the ‘indolent and vicious,’ ‘lazy,’ and ‘intemperate.” 39 The fear that if almshouses were made too attractive, “undeserving” people might dissemble and/or feign penury, illness, and injury was so powerful that it led politicians, philanthropists, and communities to intentionally immiserate the least well-off as a means of ensuring their deservingness for public assistance.

The notion that is better to intensify the suffering of the least well-off then to facilitate access to social services and benefits that in theory could invite “fakers” is so common as to be virtually emblematic of USian approaches to social welfare policy in the modern era. How else can we explain the “fear of the disability con” 40 despite the overwhelming empirical evidence showing that disability and benefit fraud perpetuated by a claimant in the US is vanishingly rare?Reference Gilman 41 While such fraud and especially health care fraud does occur, in virtually every case the malfeasant is a health care worker or health care organization defrauding government assistance programs or payors.Reference Rudowitz, Garfield and Hinton 42 In other words, the specter of hordes of “fakers” crashing social welfare regimes has no connection to the reality of benefit fraud in the US.Reference Rank, Eppard and Bullock 43

Yet the fears of deception and malingering are so powerful that they shape the very structure of USian social policy. The remainder of this essay is therefore devoted to canvassing several prominent contemporary examples that link past to present in illustrating how anxieties about malingering and feigned illness continue to animate social policy in the US.

Linking Past to Present in Connecting Malingering and US Social Policy

During the Trump Administration, 12 states sought and received permission from the US government to impose Medicaid work requirements as a condition of eligibility. Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (“CMS”) Administrator Seema Verma justified the requirements by arguing that (1) employment has a beneficial effect on health and (2) “dependency” on safety net programs is problematic.Reference Ollove 44 Yet, the policy case for Medicaid work requirements is paper-thin.

First, the vast majority of Medicaid recipients who are able to work, work. A left-leaning think tank argues that at least 60% of the people who could be subject to such work requirements already work.Reference Katch, Wagner and Aron-Dine 45 Whatever the exact percentage, there is no serious dispute that a significant majority of those impacted by these requirements already work. Even states which tried to implement work requirements noted as much: “According to one study in Michigan, CMS said, “Nearly everyone who was targeted by the community engagement requirement in Michigan already met the requirement or was exempt from it, so there was little margin for the program to increase work or community engagement among beneficiaries.” 46

Second, as several courts noted in enjoining such requirements, the principal effect of the policy change is Medicaid disenrollment. A federal district court, for example, concluded that DHHS’s granting of the waiver to impose Medicaid work requirements was arbitrary and capricious because it “entirely failed to consider Kentucky’s estimate that 95,000 persons would leave its Medicaid rolls during the 5-year project.” 47 The District Court was unimpressed with DHHS’s suggestion that alternative criteria could be used to justify the waiver because, it noted, a central purpose of Medicaid is to furnish medical assistance. Striking 95,000 citizens from the Medicaid rolls contravenes this objective. Moreover, given that most Medicaid enrollees are either ill, disabled, in school, informal caregivers, and/or poor, interrupting critical coverage has the general effect of immiserating some of the least well-off.

Third, there is no good evidence that work requirements actually increase employment rates or reduce poverty. Several studies have documented transient impacts on employment and poverty that fade to null over a five-year period. 48 A brand-new NBER paper released in June 2021 found that work requirements for a different safety net program, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (“SNAP”), increased “program exits by 23 percentage points (64 percent)” and produced a “53 percent overall reduction in program participation.”Reference Gray, Leive, Prager, Pukelis and Zaki 49 In fact, the effects on participation were so pronounced the investigators concluded that eliminating work requirements would “transfer more resources to low-income adults” per dollar of public expenditure than alternative policy interventions.

Ultimately, the policy case justifying the imposition of Medicaid and/or other safety net work requirements is so weak that very few policy organizations or think-tanks, including ideologically conservative or laissez-faire groups, publicly endorsed any of the proposals. Yet numerous politicians on both state and federal levels pursued them.

Why? How can we account for the eagerness to impose policy changes that have as their only probable effect the immiseration of the least well-off? Former CMS Administrator Verma supplies part of the answer: the need to make sure that only those who are “truly” unable to work receive public benefits. This answer of course rests again on the idea of deservingness, of ensuring that only those who are genuinely sick, injured, and/or destitute merit assistance. Ability to work has been the central feature of virtually all pension entitlements in US history, showing again how past connects to present in illuminating key features of health and social policy in the US.

The argument, thus, is that whatever explanations we generate for the eagerness to impose Medicaid work requirements in spite of at-best tepid policy rationales is incomplete if it does not include anxieties about deception, malingering, and feigned illness. The “fear of the disability con” is not simply a curious quirk of US social policy; it is rather a deus ex machina for the entire apparatus itself.

Another example are regulations governing access to Social Security for disabled people. As I have previously written, “C.F.R. § [416.929 (2017] provides that proof of disability must come by medically acceptable clinical and laboratory diagnostic techniques. A physical or mental impairment must be established by medical evidence consisting of signs, symptoms, and laboratory findings, not only by your statement of symptoms.”

This provision has particular implications for the class of people seeking disability benefits by virtue of chronic pain. Because many forms of chronic pain defy the objective armamentarium of Western medicine and health care, the population of claimants with chronic pain will likely have a much more difficult time drawing up the needed proof. This state of affairs is all the more problematic given that virtually every health professional modality charged with providing care for people in pain prioritize the patient’s subjective self-report. 50

This regulation also promotes epistemic injustice against people in painReference Buchman, Ho and Goldberg 51 inasmuch as it “mandate[s] a prejudicial credibility deficit for chronic pain sufferers — their testimony about their own experiences of illness is, as a matter of law, regarded as insufficient to justify an entitlement to disability benefits.” 52

Finally, as Dara Purvis has noted, claimants seeking Social Security benefits for disability flowing from a chronic pain condition like fibromyalgia are, as a class, much more likely to fail to satisfy the regulations because of the difficulty of producing so-called “objective” evidence of impairment. Because women are much more likely to experience fibromyalgia, the regulations themselves are gendered and intensify chronic pain stigma along gender lines. 53

This regulation demonstrates several historical threads connecting anxieties about malingering and deception to social policy. The policy evinces particular mistrust of people in pain. Only people who are “truly” disabled by pain “deserve” public assistance. And unless the cause of the disability can be shown via the objective armamentarium of Western health care and medicine, the truth of the claimant’s disability remains questionable. Thus the fear of dissimulation is deemed sufficient to obstruct or bar altogether access to welfare benefits for an entire class of people. Moreover, the regulation may have disproportionate impact on women, thereby reinforcing that some social groups (i.e., women, slaves, Black and Brown peoples, the poor, etc.) in the West seem particularly likely to be accused of feigning illness across time and space.

As a third example, consider state and federal resistance to extending or increasing unemployment benefits during the COVID-19 pandemic. In initial debates, several US senators urged that the proposed $600 weekly payments were simply too generous.Reference Cochrane and Fandos 54 Their concern was that the amount would encourage people to stay unemployed. Indeed, by June 2021, 22 states had voluntarily withdrawn from the federal government’s pandemic unemployment benefits program. Many officials in these states offered similar reasons for ending such benefits. Although the COVID-19 program supports benefits regardless of the reason for employment, concerns of “overgenerous” employment benefits have historically been intimately connected to anxieties about malingering.Reference Yelin 55 The modern argument simply launders historical tropes through the contemporary “wonkspeak” of social choice theory:

When social scientists use the term choice to discuss withdrawal from work in the face of chronic disease, they give a nice name to behavior which as easily may be called malingering. When they argue that social policy encourages the exercise of that choice to exchange labor for leisure, the response in Washington is to the image of malingering, not choice. The response is to try to get the malingerers off the disability rolls, or at least, to reduce the size of their benefits. 56

Ultimately, the policy case justifying the imposition of Medicaid and/or other safety net work requirements is so weak that very few policy organizations or think-tanks, including ideologically conservative or laissez-faire groups, publicly endorsed any of the proposals. Yet numerous politicians on both state and federal levels pursued them.

There is, of course, little evidence that during times of economic and social extremis in particular increasing unemployment benefits depresses willingness to work. Yelin’s detailed 1986 study found exactly the contrary: Increased unemployment benefits and physician-provided diagnoses had extremely weak effects on labor-force participation. The strongest effects on such participation came from variables like job autonomy (“discretion over the pace and activities of the job”), and the level of psychological demand on the worker: “The combination of low discretion and high demands reduces the probability of working by a half.” 57

Yelin also draws the critical point regarding the reach of ideas about malingering. Mostly chimerical anxieties about malingering and the implications on deservingness for public assistance are so powerful in the US they are sufficient to convince stakeholders to immiserate the least well-off: “[I]f the intent is to remove the undeserving from the rolls, all beneficiaries suffer.” 58

Conclusion

One of the most fundamental and important axioms of intellectual history is that ideas are social actors.Reference Goldberg 59 It is common to think of ideas as gossamer in contrast to the realities of the material world. But this is a grave mistake. Ideas can move mountains. To do so, ideas have to be embedded in social matrices of power, politics, and material conditions. But properly nested, ideas can and do catalyze enormous social and political change.

The point of this essay is to suggest the significant hold that fears of malingering and feigned illness have on Western societies across time and space. These ideas are powerful enough to influence social welfare policy in different societies and in different places. In the modern US, fears of malingering are, in concert with other important ideas of deservingness, merit, and responsibility, sufficient to shape the very core of what social policy does exist in the U.S. In other words, the social safety net in the US on both federal and state levels looks and functions the way that it does because of the power of fears of deception, malingering, and feigned illness.

Admittedly, the claims contained herein are merely meant to be suggestive. A great deal more scholarly work is needed to shore up the argument. While ideas of deservingness at the core of social policy across the West are connected to fears of malingering, they are not identical and the former is almost certainly broader than the latter. Explicating the precise connections between these two sets of ideas is complex and important. Moreover, this essay has not even mentioned the powerful role of religious ideas, institutions, and actors in shaping notions of merit and deservingness of public assistance in the West.

Nevertheless, while anxieties about malingering cannot fully account for the peculiar and meager scope of social welfare policy in the US, the argument here is simply that no explanation of the structure and function of US social and health policy is complete without accounting for the critical role such anxieties play.

Note

The author has no conflicts to disclose.