Charlie Chaplin was arguably the most recognisable authoritarian figure – real or fictional, clean shaven or moustachioed – in Latin America during World War II. His polemical new film, The Great Dictator, took the region by storm in early 1941 and magnified his already larger-than-life persona. From Mexico to the Southern Cone, heated congressional debates, newspaper editorials, protests inside and outside theatres and censorship greeted Chaplin's mockery of Adenoid Hynkel (Adolf Hitler) and Benzino Napaloni (Benito Mussolini). The film inspired high jinks and intrigue everywhere it went. Curious Argentines circumvented the Buenos Aires ban by taking the ferry across the Río de la Plata to Uruguay, where fascist protesters interrupted the iconic closing speech.Footnote 1 When five masked bandits in search of the film stole the wrong one from a man leaving a Paraguayan train station, others finished the job by kidnapping two theatre employees and ransacking their office.Footnote 2 Peru's ban provoked a duel of honour between a senator and the justice minister. Fortunately, their rhetoric proved sharper than their aim.Footnote 3 After pro-Axis protesters interrupted a matinee in Chile, a clever headline saluted the actor's legacy: ‘Tear Gas Bombs Attempt to Make Public Cry Instead of Laugh at Charles Chaplin.’Footnote 4

A Chaplin biographer's claim that The Great Dictator was ‘an unparalleled phenomenon, an epic incident in the history of mankind’ captured the enduring hyperbole surrounding this movie event.Footnote 5 Whereas scholarship on Good Neighbour-era films has tended to focus on how Hollywood constructed Latin American identity or represented US values in the service of hemispheric unity,Footnote 6 I instead explore the Chaplin film as a political and cultural object that generated divisiveness and unintended consequences throughout its extraordinary Latin American circulation. Much to the dismay of Latin American leaders, rancorous local debates over whether to authorise the movie trained a harsh light on their own anti-democratic impulses and raised questions about freedom of speech and artistic expression. In the months before the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, the movie unmasked regional cosiness with Axis powers Germany and Italy and subverted US efforts to recruit allies in the region. Indeed, the lack of a unified response to the Chaplin film exposed fault lines in hemispheric solidarity and laid bare the myth of Latin American political unity during World War II and the ensuing Cold War.Footnote 7

By any metric, The Great Dictator was no orthodox Hollywood export. Although almost universally adored, Chaplin was 50 years old and had begun incorporating sound scenes only a few years earlier in Modern Times (1936). The English actor had worked most of his adult life in Hollywood playing variations of ‘The Tramp’, but Chaplin defied facile national and ethnic categories. Despite ambivalence about Hollywood's rise in the early decades of cinema, Latin American intellectuals had extended to Chaplin ‘honorary latinidad’, celebrating the actor and his characters as anti-imperialist icons and praising Chaplin's resistance to industry and market demands through pursuit of the ‘pure art’ of silent film into the 1930s.Footnote 8 Chaplin refused to become a naturalised US citizen and paid a dear price for this decision during the 1950s Red Scare, when the United States revoked his re-entry visa.Footnote 9 Although Chaplin was not Jewish, Hannah Arendt named him an honorary ‘schlemihl’ [sic] because he ‘epitomized in an artistic form a character born of the Jewish pariah mentality’.Footnote 10 The myth of Chaplin's Jewishness galvanised critics left and right.Footnote 11 The Chilean protester who yelled at the screen, ‘Down with the Jew Chaplin!’, was hardly the only person in the Americas or Europe to confuse the actor with his on-screen persona or to hurl an anti-Semitic epithet at the movie star.Footnote 12

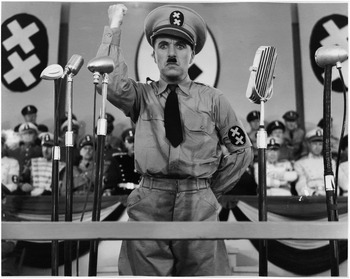

Figure 1. Charlie Chaplin delivers a speech in perfect German gibberish in his most political and controversial film, The Great Dictator

Unlike most Good Neighbour cultural products, the Chaplin film did not portray Latin American people and places or seek to erase differences between the United States and its neighbours to the south. For example, the homogenising musical Flying Down to Rio (Thornton Freeland, RKO Radio Pictures, 1933) and Disney's ethnographic Saludos Amigos (Wilfred Jackson et al., 1941) attempted to build ideological and cultural consensus and instruct US audiences about Latin American customs and traditions. In stark contrast, The Great Dictator mocked Western liberal democracy's most notorious villains and challenged what audiences had come to expect from the silent screen's biggest star (Figure 1). Never had Chaplin produced a full-dialogue film, much less a brash political manifesto in which a Jewish barber masquerading as an instantly recognisable totalitarian leader spent the final six minutes lecturing the world on tyranny. The first Latin American audiences to see The Great Dictator probably saw subtitled versions, which created translation challenges in a region with many local variations of castellano.Footnote 13 A Chilean film producer in 1941 disparaged the ignorant moviegoer who could not ‘read fast enough to make out the Spanish sub-titles’, a patronising suggestion that Latin Americans were not sophisticated enough to appreciate Hollywood films.Footnote 14

Focusing on the countries in which the US State Department and diplomats devoted the most concern to the film's reception, I explore the inordinate discord and conflict surrounding the movie north and south of the Río Grande. Washington hoped Chaplin's biting satire would send the message to Latin Americans that totalitarianism was an unacceptable alternative to a democratic order, but even US viewers could not agree on whether the film advocated intervention in or isolation from the impending world war. Argentina, Peru and Chile feared the film would insult influential German and Italian communities at a moment when the war's outcome was still in doubt, and, in fact, Peruvian and Bolivian officials stored the film in safes to prevent public showings.Footnote 15 Nicaragua's Anastasio Somoza García was convinced that his decision to allow the film cloaked his authoritarian rule in democratic principles.Footnote 16 This proliferation of available meanings only made the public more anxious to see what the fuss was about. Indeed, Chilean president Pedro Aguirre Cerda reportedly authorised the film only after his wife overruled his ban.Footnote 17 As a complex signifier and carrier of Western imperialism, the movie underscored both the limits of US political and cultural hegemony and Latin American resistance strategies more broadly.Footnote 18

Although scholarship on Nazism in Latin America has focused on Argentina, Brazil and Chile, The Great Dictator suggests that sympathy for the Axis cause existed throughout the region during the supposed ‘golden era’ in US–Latin American relations.Footnote 19 The metaphor of the Good Neighbour was intended to serve various imperialist goals, not the least of which was the creation of an ‘imagined consensus’ among diverse and far-flung groups.Footnote 20 Yet the bold, big-budget Chaplin film jeopardised the United States’ own Good Neighbour redemption narrative. Indeed, Latin Americans always had to negotiate multiple relationships, ideological currents and cultural identities – even on the eve of World War II in a century increasingly defined on US terms.

‘Hail Hynkel!’

The Good Neighbour era (broadly defined as 1928–47) represented a significant, if at times cosmetic, shift in how the United States engaged its brethren to the south. After decades of gunboat, big-stick and dollar diplomacy, Washington vowed to follow a gentler approach. Although no portrait of the Good Neighbour period is complete without Hollywood, the film industry's cultural authority and reach was at once promising and problematic. At home, Hollywood's fascination with wartime themes blurred the lines between entertainment and propaganda and raised serious questions about government control of an important vehicle of mass communication.Footnote 21 Down south, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt's new motion picture initiative demanded a gentler portrayal of life throughout the Americas – no small challenge for an industry long notorious for negative Latino stereotypes.

Recognising the geopolitical importance of cultural exchange, Roosevelt created the Office of the Coordination of Inter-American Affairs (CIAA) in 1940 to counter Nazi propaganda in the region using films, news and advertising. Movies were central to the CIAA's mission, which promoted goodwill tours by Hollywood figures such as Carmen Miranda, Orson Welles and Walt Disney and began sanitising the industry's unflattering portrayal of Latin American people, themes and places.Footnote 22 Since Hollywood's earliest days, films had referred to Hispanics using racial epithets such as ‘spic’ or ‘greaser’ and characterised males as slothful and ignorant peasants who spoke broken English.Footnote 23 US and Latin American audiences alike consumed these cinematic depictions. In 1940, the United States produced three-quarters of Latin America's big-screen offerings across 5,400 theatres, not all of which were wired for sound.Footnote 24 The campaign to produce films with Latin American content paid dividends: by 1945, Hollywood had completed 84 movies set in the region.Footnote 25

As the war closed European and Asian markets to US films, Latin America offered Hollywood eager audiences but uneasy political landscapes. The Great Dictator entered this milieu as a blessing and a curse for US foreign policy. Although Chaplin's unrelenting ridicule of Hitler and Mussolini articulated US disdain for totalitarianism, the film threatened to alienate influential German and Italian populations in the region. More than 1.5 million ethnic Germans lived in South America on the eve of the war, concentrated mostly in Argentina, Brazil and Chile but with small, close-knit communities in many other areas.Footnote 26 US press reports and embassy notes betrayed acute anxiety about a Latin American ‘fifth column’, the supposed German, Italian and Japanese hordes waiting to rise up within the body politic. An excitable Associated Press reporter arrived in Peru in mid-1940 to investigate clandestine Nazi activity and found himself ‘in the midst of a silent war for control of the continent, the opening battle for domination of the whole Western Hemisphere’.Footnote 27 American, British and German films transformed theatres into political and ideological battlegrounds. A Nazi theatre owner in Lima reportedly paid a rival to close its doors rather than offer Hollywood fare to the public.Footnote 28 A US diplomat could hardly bear that a fascist Paraguayan impresario was showing a German propaganda film in the same theatre as Gone with the Wind (Victor Fleming, Selznick International Pictures, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1939).Footnote 29

Given this climate, a polemical film based on Chaplin's striking resemblance to Hitler was almost certain to create an international firestorm. In the 1930s, pundits and political cartoonists had noted the likeness between the Tramp and the tyrant, who were born four days apart in April 1889 and reportedly shared a passion for Polish silent film star Pola Negri or her films or both.Footnote 30 Identical toothbrush moustaches proved a remarkable visual identifier that fused the two in the imagination. Chaplin prepared for the role by watching Hitler newsreels in his home theatre or the studio's projection room and concluded that the real-life dictator was ‘the greatest actor of all of us’.Footnote 31 The infamous clip in which Hitler appeared to dance after signing the French surrender in June 1940 prompted an angry response from Chaplin: ‘Oh, you bastard, you son of a bitch, you swine. I know what's in your mind.’Footnote 32 Nonetheless, Chaplin's treatment of his doppelgänger was a risky professional endeavour. The star of Modern Times was beginning to appear behind the times. The Great Dictator cost a hefty US$ 2 million to make and faced uncertain European and South American wartime markets. What's more, Chaplin conceived and developed the picture at a moment when most Americans were against intervention in Europe.Footnote 33

The film cast Chaplin as both Adenoid Hynkel, Dictator of Tomainia, and a Jewish barber who has spent 20 years hospitalised with amnesia following a Great War aircraft accident. On returning to the Jewish ghetto, the barber is confused to discover that storm troopers from Hynkel's Double Cross Party are persecuting Jews. Two stacked Xs, echoing the German swastika, symbolise the party. Chaplin's wife, actress Paulette Goddard, plays the winsome Hannah, the barber's love interest. A military officer (Reginald Gardiner), whose life the barber had saved, initially offers protection, but Hynkel escalates his anti-Semitic attacks after a Jewish financier refuses him a loan. Vaudeville performer Jack Oakie plays Benzino Napaloni, the boisterous Dictator of Bacteria who plots with Hynkel to invade Osterlich. In a rare concession to propriety, Chaplin decided against calling Oakie's character the more recognisable ‘Benzino Gassolini’ because Italy was still neutral at the time.Footnote 34 Chaplin and Oakie sometimes remained in character as Hynkel and Napaloni after leaving the studio and once showed up in costume at a party hosted by actress and producer Mary Pickford.Footnote 35 The script was inordinately long at nearly 300 pages, and production lasted 168 days.Footnote 36

If initially uncomfortable with sound, Chaplin appears to combine speech and slapstick with ease. Newsreel study sessions paid off when Chaplin improvised a Hynkel speech in fluent German gibberish with perfect Hitler mannerisms. Quips were fast and furious (Commander Shultz: ‘Strange, and I thought you were an Aryan.’ Jewish Barber: ‘No, I'm a vegetarian.’). No words were needed for Hynkel's poetic ballet with a giant balloon globe in his oversized office (the balloon, and presumably his plans for world domination, burst in his face). Nonetheless, speech proved potent and controversial in the final scene. After the barber escaped from a concentration camp, Hynkel's troops mistook him for the dictator. Posing as Hynkel, the barber delivered a passionate six-minute speech and radio address in defence of democracy:

Even now my voice is reaching millions throughout the world, millions of despairing men, women and little children, victims of a system that makes men torture and imprison innocent people. To those who can hear me, I say, ‘Do not despair.’ The misery that is now upon us is but the passing of greed, the bitterness of men who fear the way of human progress. The hate of men will pass, and dictators die, and the power they took from the people will return to the people. And so long as men die, liberty will never perish.

Near the end of the speech, the barber reaches out over the airwaves to Hannah, who had fled with her family to Osterlich only to face more Double Cross persecution.

The Great Dictator debuted 15 October 1940 at the Capital and Astor theatres in New York, where it ran for 15 weeks to mixed reviews. Isolationists and interventionists found fault. The closing speech violated Hollywood conventions of the era. Not only was the movie Chaplin's most political and ideological, but the conclusion did not neatly sew up narrative threads and left the barber's fate either unclear or all too clear. The speech scene comprised long, uninterrupted camera shots rather than cutting back and forth between Chaplin and his audience.Footnote 37 Even Pickford found it ‘deplorable that he who gave so much to the world turned his back on the tramp and entered politics by introducing such themes into his pictures. When he did he lost me.’Footnote 38 Stung by widespread criticism, Chaplin defended the speech in a letter to the New York Times just a week after the film opened: ‘To me it is the speech the barber would have made – even had to make … May I not end my comedy on a note which reflects, honestly and realistically, the world in which we live, and may I not be excused for pleading for a better world?’Footnote 39 Although many critics saw the ending as a mistake, most concluded that the film was not to be missed.

Shortly after the film premiered, Roosevelt called Chaplin to the White House and greeted him thus: ‘Sit down, Charles; your picture is giving us a lot of trouble in the Argentine.’ The president, however, did not mention the picture again during a 40-minute meeting, in which he plied Chaplin with dry martinis, which the actor ‘tossed down quickly from shyness’.Footnote 40 One theory is that Roosevelt was upset not that the film angered Argentines but that Chaplin urged soldiers against becoming ‘cannon fodder’, a pacifist line the actor later repeated at pro-isolationist rallies. Although enthusiastic Londoners endured air raids to see the film when it debuted in England on 15 December, it generated controversy in Latin America from the moment it arrived.Footnote 41 The movie did not merely reflect an unstable Good Neighbour landscape but helped construct the very disharmony and divisiveness that Washington and Latin American governments feared.

Translating Hegemony in Argentina

The US embassy reported in late December 1940 that the Argentine Board of Censors had cleared The Great Dictator, which was scheduled to debut 2 January in three Buenos Aires theatres.Footnote 42 As international markets collapsed, Hollywood viewed Argentina's 1,208 movie houses as important surrogate outlets.Footnote 43 However, Mayor Carlos Alberto Pueyrredón soon capitulated to the Italian ambassador's ‘friendly request’ and revoked permission for the Chaplin comedy and for the Edward G. Robinson thriller Confessions of a Nazi Spy (Anatole Litvak, Warner Brothers, 1939).Footnote 44 The Buenos Aires ban was hardly surprising. Much to Washington's discomfort, Argentina remained neutral until March 1945, the last Latin American holdout. In the ensuing public debate about the ban, many Argentines encountered the Chaplin picture as a contentious cultural and political object. The film exposed tensions in the country's attempt to maintain its sovereignty as well as resistance to Roosevelt's plan to unite an American hemisphere against the Axis powers.Footnote 45

The Chaplin film mobilised longstanding tensions between the United States and Argentina. Competing hegemonic designs on the region had caused friction between the two since the late nineteenth century. After the Great War, the United States’ emergence as the world's major power and Argentina's retreat into its ‘protective’ relationship with Great Britain and refusal to submit to Washington's dictates undermined Good Neighbour détente.Footnote 46 Relations were cool. In a 1932 speech before the US community in Buenos Aires, humourist Will Rogers claimed that ‘Argentina exports wheat, meat and gigolos, and the United States puts a tariff on the wrong two.’Footnote 47 Amid the 1930s economic crisis, some Argentine nationalists feared overreliance on Britain and began gazing toward Germany and Italy to soften that dependency. When the United States entered the war, Washington expected the region to fall in line.Footnote 48 Secretary of State Cordell Hull later called the Argentine government's refusal to do so ‘a crime against democracy’.Footnote 49 Although some politicians, military officials and diplomats favoured closer relations with Germany and Italy, most Argentines supported the Allied cause despite suspicions about US foreign policy.Footnote 50 Conflicting ideological currents in general, more than the Allies–Axis debate specifically, betrayed concern over the impact of foreign alliances on domestic politics and economics.Footnote 51

Unsurprisingly, the US embassy perceived the Buenos Aires prohibition of the Chaplin film as buckling to Italian demands.Footnote 52 Ambassador Norman Armour speculated that the foreign relations minister did not wish to rile Argentina's million or so Italians, who he claimed were ‘refraining from fifth column activities or propaganda as conducted by the Nazi groups here’.Footnote 53 The pro-Allied press excoriated the ban. La Prensa called for a rejection of the Italian request in the name of freedom of expression and national sovereignty.Footnote 54 Crítica charged that the mayor's prohibitions of films and of the D. H. Lawrence novel Lady Chatterley's Lover (1928) were ‘reducing the first Spanish speaking city to the status of a town of semi-illiterate [Q]uakers through his picturesque moralizing decrees’.Footnote 55 Argentina's loss was Uruguay's gain. Travel companies began organising excursions that ferried filmgoers to Montevideo and Colonia, where the film played at the Cine Trocadero and Cine Stella, respectively, amid controversy.Footnote 56 On 18 January 1941 in Montevideo, five protesters reportedly interrupted the final scene by yelling, ‘I'm a fascist!’ Police arrested nine. The United States embassy and press reported that an ‘enthusiastic applause from the public’ drowned out protesters.Footnote 57

The film polarised Argentine lawmakers and ignited heated discussions about artistic merit and censorship. In early February, the movie hijacked a Chamber of Deputies debate on fraudulent provincial elections. A headline in an English-language newspaper, ‘Charlie Chaplin in Chamber’, underscored how the film insinuated its way into spaces beyond the theatre. Juan Antonio Solari, a Socialist deputy, criticised President Roberto María Ortiz for ignoring totalitarian infiltrations while obsessing over a film that ‘was in reality a defence of democracy’. By banning the movie, the president ‘was simply defending ideas which could never be accepted by any free-thinking Argentine’.Footnote 58 Solari dismissed the threat of disturbances and questioned if Buenos Aires deserved censorship that ‘offended its culture and spirituality’.Footnote 59

However, others supported the ban. Deputy Miguel Osorio of the conservative Partido Democrático Nacional (National Democratic Party) had seen the film and was unimpressed: ‘It can do nothing else but awaken racial hatred. It is grotesque and insulting, without art, lacking in genius and, altogether, a bad picture. It is an insult to culture and it is daylight robbery to charge the public to see it.’ The lawmaker muddled an otherwise principled message when he asserted that if ‘Chaplin wished his poor effort to be a vehicle of democratic propaganda, he should have insisted that the film be shown free everywhere’. In other words, the film's most serious transgression was not incivility toward German and Italian communities but charging for it. After further exchanges, the chamber leader managed to steer discussion back to the voting question.Footnote 60

Competing Argentine authorities seemingly approved and banned the film more times than Tomainians shouted ‘Hail Hynkel!’ The New York Times reported that officials might lift the ban if distributors agreed to cuts, including the ghetto scene in which ‘Nazi storm troopers hurl tomatoes at Paulette Goddard, and deletions in Chaplin's speech at the end, particularly where he exhorts the Nazi soldiers to lay down their arms and “not give yourselves to these brutes (the dictators) who regiment your life and use you as cannon fodder”’. Other suggested cuts were more puzzling, including Hynkel's scamper up the office curtains and Nazi soldiers’ mistreatment of Napaloni's full-figured wife.Footnote 61 In June, the Buenos Aires Municipal Council overrode the ban, but the federal government again bowed to Italian and German pressure.Footnote 62 In October, based partly on the council's decision to permit the film, new President Ramón S. Castillo dissolved the body and sent police to occupy its chambers.Footnote 63

The Chaplin debate dragged on into November, when the Buenos Aires Herald criticised the ‘Nazi embassy’ for its ‘self-assumed right to decide what class of entertainment shall be provided [to] the Argentine audiences’. In this view, the prohibition threatened individual liberties and democracy: ‘Argentines fought so long ago for their freedom, and have enjoyed it for so many years that they are not prepared to yield it up at the dictate of any jack-booted European who feels inclined to crack the whip.’Footnote 64 The editorial implicitly indicted an Argentine government that deprived a cultured society of the right to view an artistic production. By 1943, 40 US motion pictures were either banned or withheld rather than be submitted to Argentine censors. Washington's wartime embargo of raw film stock helped topple Argentina's thriving domestic film industry from atop the Spanish-language market.Footnote 65

To be sure, Chaplin's anti-totalitarian rhetoric was not Hollywood's only wartime challenge in Argentina. In May 1941, the Ritz Brothers and Andrews Sisters musical Argentine Nights (Burlones Burlados, Albert S. Rogell, Universal Pictures, 1940) provoked a near audience riot at the Suipacha theatre in Buenos Aires. Police intervened.Footnote 66 One critic argued that the presence of Argentine gauchos, bull fighters, Mexican charros (horsemen) and an international polo champion, all of whom fired pistols into the air when greeting friends, represented an insulting mishmash of Latin American stereotypes.Footnote 67 La Nueva Provincia of Bahía Blanca cringed at the depiction of gauchos living in a ‘sort of tropical jungle’. Ignoring shifting cinematic depictions of gauchos over time, the newspaper charged that movies would not advance the Good Neighbour Policy ‘unless the North American film industry, which still dominates the continental market, begins to turn out more faithful reproductions of national types and customs’.Footnote 68 The US embassy blamed the Argentine Nights disturbance on pro-Nazi agitators, reporting that some broke out into the Argentine national anthem and shouts of ‘Heil Hitler!’Footnote 69

The Great Dictator and the months-long debate over the Chaplin film underscored a unique dilemma: Argentina's desire to negotiate a favourable international position, assert its independence from the United States and European powers, and keep trading options open. Especially pronounced was the moral indignation that a governmental authority – local, national, or foreign – might determine what citizens might read, watch, or debate. Even more galling in the country in which Domingo Sarmiento had characterised the city as civilisation and the pampa as barbarism, different censorship laws permitted audiences in the province of Entre Ríos to see the film, something their Buenos Aires counterparts could not do.Footnote 70

Curtains for Chaplin in Peru

Scholarship on wartime South America has largely ignored Peru's role as a fierce strategic and ideological battleground. The large Amazon region, long Pacific coastline and substantial Italian, German and Japanese populations stirred wild fantasies in Washington. As early as the 1920s, US officials feared that Germany could sweep up the Amazon River and attack the Panama Canal using retrofitted commercial aircraft.Footnote 71 Although Peru found itself wedged between pro-Allies and pro-Axis contingents when The Great Dictator landed in January 1941, the arrival coincided with the latest episode in a century-long border dispute with Ecuador. Peruvian officials calculated that Washington was too distracted with European events to worry about a conflict over small coastal and jungle zones in the Andean region. Given Peru's superior forces against a country with little air power, the war was over in less than a month.Footnote 72 The victory soothed painful memories of the War of the Pacific debacle against Chile six decades earlier, and, as a bonus, allowed Peru to thumb its nose at the United States. Unfortunately for Chaplin fans, the Peruvian government's willingness to defy Washington's campaign for hemispheric solidarity extended to The Great Dictator, which did not get a public showing until Peru severed its Axis ties in January 1942. Whereas Argentine officials wavered over the movie for months, Peruvian leaders never showed public signs of relenting and allowing it to be shown.

Peru's prohibition of the Chaplin film exposed the disproportionate influence that small Italian and German communities wielded in the Andean country. Despite a 1941 population of just 7,618 (all but 688 in Lima and Callao), Italians were well positioned in banking, utilities, manufacturing and commercial networks. Indeed, the Banco Italiano was Peru's largest financial institution. The 2,122 Germans (all but 480 in the capital) were mostly dedicated to trade, banking and sugar farming. Beyond a small community around the Casa Grande sugar plantation on the north coast, most were concentrated in the wealthy Lima suburb of Miraflores, where they rubbed shoulders with Peru's middle and upper classes.Footnote 73 Unlike their Italian and German counterparts, Peru's 26,761 Japanese endured racialised violence and economic resentment. A rumour that 3,000 machine guns had been discovered in a Japanese flower garden on Lima's Avenida Brasil ignited riots against Japanese businesses in 1940.Footnote 74 Similar unfounded rumours spread rioting in Chancay and Huaral, resulting in an estimated US$ 7 million in damages to 600 businesses and homes. In one of the sorriest episodes of the war, Peru bowed to US pressure, rounding up hundreds of Japanese and German nationals and shipping them to internment camps in Texas and New Mexico.Footnote 75 In all, 4,058 Germans, 2,264 Japanese and 288 Italians were deported.Footnote 76

Peru was already in the middle of an intense propaganda war when The Great Dictator arrived. US embassy notes and press reports were certain that a well-oiled German information operation had ‘taken quarters on the top floor of the Bolivar Hotel’, where the German news agency Transocean churned out Axis propaganda.Footnote 77 In colourful but hyperbolic prose, Associated Press reporter John Lear described the remote Peruvian jungle town of Iquitos as a tropical Berlin, where boats delivered ‘bales of German propaganda’, movie houses showed German films, and a ‘Nazi stooge’ held an important position in the Chamber of Commerce. Indeed, ‘Nazis seemed to be everywhere, agitating, threatening, proselytizing, drilling.’Footnote 78 Underscoring how seriously the United States took the German threat, Washington opened a wartime vice consulate in Iquitos to wage economic warfare against Axis powers and manage the shipment of jungle products. Vice Consul Henry Kelly recalled that massive quantities of CIAA material such as posters, pamphlets and magazines arrived in Iquitos by river. The organisation's glossy magazine, En Guardia, was especially popular in Iquitos: ‘On Saturday afternoons – the time set aside for distribution to the man in the street – the office was stormed by mobs of bare-footed cholos, long-haired Chama Indians, enlisted men of the Jungle Division, and Indian women and children, all asking for proh-pah-GAHN-dah.’ Though arriving late and threaded into outdated projectors, US, Mexican, British and French films eased geographic isolation for eager Iquitos movie-goers.Footnote 79

At the levers of Germany's propaganda machine in Lima was Ambassador Willy Noebel, a vigilant government functionary who bristled at any perceived cinematic slight of Hitler, German soldiers and the Nazi salute, and at the mention of Reich concentration camps. Noebel had imported 5,000 Chesterfield cigarettes and a small cinema projector for personal use in September 1940.Footnote 80 Imagining the ambassador hunkered down in a dark screening room, the projector's light flickering across billowy smoke clouds, requires no great leap. Noebel's office filed a constant stream of film-related protests with the Peruvian foreign minister, including an ‘incomplete’ list of 31 US, Russian and French pictures he found ‘tendentious’.Footnote 81

The German legation's description of objectionable scenes often was as titillating as the scenes themselves. The ambassador complained that the Hollywood film Nurse Edith Cavell (Herbert Wilcox et al., Imperadio Pictures and RKO Radio Pictures, 1939) depicted German soldiers clicking their heels excessively and wearing their helmets indoors and in the presence of women, which ‘even a child in Germany knows perfectly well [are] not the customs of the German Army’. Noebel also claimed that the film portrayed the Belgians, French and English as ‘angels in human form’ and Germans as ‘tyrannical, brutal, and revolting’, some with the ‘repulsive features [seen in] certain American “gangster” films’.Footnote 82 The legation cried foul when The Man I Married (Irving Pichell, Twentieth Century Fox, 1940) suggested that concentration camp guards were ‘open to bribery’, that a prisoner had died ‘not from a natural death’, and that Hitler rivalled Attila the Hun and Genghis Khan.Footnote 83 Equally objectionable was Arise My Love (Mitchell Leisen, Paramount Pictures, 1940), in which Tom Martin (Ray Milland) taught a rat named Adolf to perform the Nazi salute.Footnote 84

The German legation requested that Peru ban the Chaplin film even before its 25 January arrival.Footnote 85 However, local United Artists manager Victor Schochet was confident that the Patronato Nacional de Censura de Películas Cinematográficas (National Board of Cinematographic Film Censorship), which screened the picture on 27 January, would approve it with only minimal cuts. Leading indicators were positive. Schochet planned to open the new San Martín theatre with the Chaplin film on 5 March.Footnote 86 The Senate and Chamber of Deputies supported showing it. Ambassador R. Henry Norweb reported that the censorship board stood ‘three to one for it’.Footnote 87 The final decision rested with President Manuel Prado and Minister of Justice Lino Cornejo.Footnote 88

The Great Dictator acquired new gravity as it flowed through the region, altering the way the public and public officials responded to it.Footnote 89 In January, Lima newspapers reported on the film's rocky reception in Argentina, Chile, Mexico, Venezuela, Uruguay and Costa Rica.Footnote 90 The censorship board, newspaper editors, politicians and others found themselves debating not just the film but its growing history as well. Aware of the film's turbulent circulation, the pro-Allies La Crónica criticised the Buenos Aires prohibition and touted Chile's and Bolivia's decisions to show a film ‘that has produced such a sensation in the world’. The editorial praised Chaplin for producing pictures ‘not for their value as a technique of cinematic art but rather as a mirror of the customs and moralisation of human society’.Footnote 91 While conveying Hollywood's tepid reception of the film, a Lima magazine recognised that world events granted the movie ‘greater timeliness each day’.Footnote 92 The Peruvian debate illuminated how a controversial cultural product gathered up and mobilised diverse groups of people and interests, and, in the process, frustrated those who most desired to control it.

Unfortunately for Chaplin, this accumulated history contributed to the film's prohibition. On 3 March, the censorship board notified United Artists Corporation that it had banned the Chaplin picture.Footnote 93 Alfredo Solf y Muro, Peru's minister of foreign affairs, denied to Norweb that German and Italian protests had influenced the decision. Although Solf had not viewed the film, he understood it to be in ‘bad taste’ and expressed concerns about its effect on ‘internal order’. Norweb blamed the decision on cowardice, asserting that officials found it ‘simpler to ban the film and run the risk of a congressional protest than to allow the film to be shown with the possibility of having to call out the police to quell possible disturbances’. Still fresh in local memory was The Lion Has Wings (Alexander Korda et al., London Films Productions, 1939), a British propaganda documentary that Norweb claimed had caused ‘trouble and several broken heads’ in Lima.Footnote 94

After Peru's quick defeat of Ecuador in July, The Great Dictator debate resurfaced when the Senate and Chamber of Deputies requested that the foreign minister overturn the ban. When censors declined, a heated senate session and at least one duel revealed deep divisions over the film. Senator Andrés F. Dasso, whose family had emigrated from Italy, claimed to have seen the picture in New York and found ‘absolutely nothing interesting and in fact much that is grotesque’ about it: ‘I am certain that the prestige of democracy will not be saved by a ridiculous film by Charlie Chaplin. Democracies are effective when they are built upon a base of respect that nations owe each other.’Footnote 95 Senator Celestino Manchego Muñoz countered that most South American countries had shown the picture without harming foreign relations. With the country's virile new image in mind after a complete military victory, Manchego lamented that

only Peru allows restrictions of that nature, which present us as a timid nation without the necessary liberty to take a position due to the fear that it might affect in some way the sensibilities of other nations. It is high time to react against a sign of weakness that compromises the prestige of the country.

Manchego asserted that Cornejo, the justice minister, had locked the Chaplin film in a bank vault and refused to allow even lawmakers to view it.Footnote 96 His implicit charge of cowardice apparently was too much for Cornejo to bear. Four days later, in a duel at the Pampa de Amancaes, the two exchanged two pistol shots each without injury and afterward failed to reconcile. Cornejo tendered his resignation due to a ‘personal matter’, but the president declined it.Footnote 97

However, Peru's anti-Yankee streak proved ephemeral. On 29 January 1942, less than two months after Pearl Harbor, Cornejo informed the German legation of Peru's decision to break diplomatic and consular ties with the Reich ‘as an expression of solidarity with the United States of America’. That same day, Noebel requested protection and safe conduct out of Peru.Footnote 98 In the years ahead, the Andean country became one of the United States’ strongest allies.Footnote 99 Washington coveted Peruvian rubber, petroleum and other raw materials, and was willing to build airfields in exchange for a foothold in the Pacific region. At President Roosevelt's invitation, Peruvian President Manuel Prado flew to Washington in May 1942 for the first state visit ever by a sitting South American leader. Just months after Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt, Secretary of State Cordell Hull, luminaries such as Nelson Rockefeller, and multiple 21-gun salutes greeted the Peruvian president at the Washington airfield. In a Rose Garden press conference, Prado minimised the threat of a Japanese fifth column in Peru and invited Americans to the Andes, where there was plenty of sugar and ‘no gasoline rationing – yet’.Footnote 100 The war had brought Peru even more solidly into the US economic orbit.Footnote 101

Unique Geopolitical Contexts

The Great Dictator mobilised diverse groups and political issues wherever it went, but the diplomats, thieves, policemen, impresarios, politicians and others who confronted the film inside and outside theatres never succeeded in harnessing its message.Footnote 102 Beyond Argentina and Peru, the movie served as a vehicle for anti-Semitic anger in Mexico and pro-Axis zeal in Chile and Paraguay, and after arriving on a Pan American-Grace Airways flight to Bolivia in April, the film became entangled in the diplomatic showdown between Washington and La Paz over raw materials and economic assistance. In no two places were the groups and interests that cohered around the film the same. The movie served as a unique catalyst for various agendas, thwarting Washington's control as well as local resistance to US hegemony. Paradoxically, as I demonstrate in this section, the Chaplin film ignited heated debates less about US imperialism and Hollywood vulgarity than about Latin America's own sovereignty, democratic openness and Old World alliances.

In early January 1941, the US embassy reported that the Palacio Chino, one of Mexico City's most modern theatres, had received threats over the Chaplin film. Police soon apprehended five suspects, including alleged instigator Adolfo León Osorio, who was accused of releasing ‘stink bombs’ and ‘itching powder’ inside the movie house. The accused claimed that a man named ‘El Paisano’ had paid them five pesos each to interrupt the film. Several reported seeing in Osorio's office anti-Semitic propaganda that included these words: ‘Mexicans, let us defend ourselves from the Jewish invasion. Fight against the Jewish lies.’Footnote 103 A poster near the theatre asserted that Chaplin and Goddard were Jews named Tonstein and Levi, respectively, and that Chaplin once had worked in New York's Jewish Theater.Footnote 104 Mexicans were hardly the only ones to buy into the myth of Chaplin's Jewishness. Even Jews had long read the actor's body language, facial expressions, attire and dispossessed characters as confirmation of a secret identity.Footnote 105 Osorio asserted that Jews controlled the Palacio Chino and other movie houses that showed Jewish propaganda and vowed to continue his ‘nationalist campaign, which is to save my country from the Jewish claws’.Footnote 106 Nonetheless, United States officials reported that most patrons ‘loudly applauded’ the film and resented pro-Axis disturbances.Footnote 107

Far to the south, Chilean protesters staged the most aggressive attacks against the film. Four Santiago theatres sold out in advance. Mindful of disturbances, management announced over loudspeakers, ‘This is Chile, a free country’, and implored dissenters to exit without incident. However, Ambassador Claude G. Bowers reported that a Nazi sympathiser at the Santa Lucia theatre ‘attempted to quell the applause of one of his neighbours. A free-for-all ensued and the provocateur was removed, after having sustained a broken nose.’Footnote 108 Disorder also rattled the Victoria and Imperio theatres in Valparaíso, where crowds collected outside movie houses in anticipation of clashes.Footnote 109 Tear gas released during a matinee at the Victoria twice forced patrons to the exits. Angry at the inconvenience, the crowd fingered two culprits who ‘moments earlier had broken out in strong yelling against the principal actor in the film’.Footnote 110 At the Imperio, pro-Axis partisans protested in the foyer and interrupted the matinee. An Italian veteran of the Great War reportedly shouted, ‘Down with the Jew Chaplin!’Footnote 111 Tear gas also punctuated the night-time showing at the Victoria. Police later arrested six members of the Movimiento Nacionalista de Chile (Chilean Nationalist Movement) and found more than two dozen tear-gas bombs and incendiary devices in the group's headquarters. Several confessed to the theatre attacks, including one who had planned to set the screen ablaze.Footnote 112

Criticism followed ideological lines. The conservative Santiago newspaper El Mercurio lambasted the picture:

Chaplin's great humour has suffered an eclipse. His comedy, always ennobled by a resigned sadness, and his grotesque adventures, embellished with a melancholy smile, have practically disappeared in this case. More than beauty, you see aggression; more than the artist, you see the adversary of a regime. It is not a work of humour. It is an act of belligerence.

Despite praise for the barber's chair and globe scenes and some Napaloni antics, the reviewer considered the final speech disastrous: ‘The call for nations to seek peace, work, and fairness is filled with good intentions. But artistically, it is a catastrophe. Moralistic stories are insufferable. And this is a moralistic story.’Footnote 113 A German embassy official reportedly called the film ‘an unpleasant picture for German residents’.Footnote 114 Although most US diplomats promoted the film with notable restraint, Bowers desired increased diplomatic pressure on Chile and fretted that his German counterpart's ‘bulldozing methods’ were cowing Chilean officials into prohibiting anti-Axis films.Footnote 115 An American consulate reported that the Germans had rushed one of their own propaganda films by plane to Valdivia, perhaps as a way to neutralise Chaplin's picture.Footnote 116 A significant German ethnic population and a 4,000-mile coastline perceived as vulnerable to submarine attacks contributed to Chile's reluctance to break with the Axis powers until January 1943.Footnote 117

To be sure, films and newsreels that cast the United States in an unflattering light were problematic as well. Bowers feared that Abbott and Costello's light-hearted Buck Privates (Arthur Lubin, Universal Pictures, 1941) might convey to Chileans ‘the notion that Americans are not really good military men’. Another of the duo's films, Keep ’Em Flying (Lubin and Ralph Ceder, Universal Pictures, 1941), carried the disclaimer ‘that the picture was a comedy and in no way portrayed actual army life’.Footnote 118 An embassy informant in Chile fretted that Pacific Blackout (Ralph Murphy, Paramount Pictures 1941), in which a United States pilot fainted after learning that a real bomb had replaced a dummy one during training, might damage the flying forces’ image. When ‘this scene appeared, the audience in the theater screamed with laughter’.Footnote 119 Newsreels had to navigate their own minefields. Bowers reported that a Paramount newsreel in Chile ‘showed pretty girls kissing soldiers for publicity purposes and made United States Army life look somewhat ridiculous. We heard criticism of another short film which revealed a too extensive use of bathing beauties in a campaign to sell defense bonds.’ The ambassador frowned upon newsreels that ‘try to mix too much sex into the defense effort’.Footnote 120 These exchanges suggest that US embassy officials paid obsessive attention to all big-screen offerings during the war.

Disputes over Bolivian oil and tin and US economic and military aid greeted The Great Dictator’s arrival in Bolivia, where the film remained in a safe awaiting authorisation.Footnote 121 Four years earlier, Bolivia had nationalised Standard Oil of New Jersey properties after the 1932–5 Chaco War fiasco against Paraguay. The diplomatic stalemate endured until July 1941, when an alleged pro-Nazi coup attempt alarmed Washington and eased the way to a settlement. Washington gained access to important wartime resources and secured another hemispheric partner; Bolivia received Lend-Lease assistance and economic aid. Along with Peru, Bolivia severed its Axis ties in January 1942.Footnote 122

The movie sparked a robust debate in the Bolivian press and congress about democratic openness and constitutionality. La Razón lamented that a democratic country had to pass a bill authorising the film and sneered at peevish Nazi proponents: ‘The foundation of a political credo such as Nazism must be fragile when the innocent exhibition of a film can endanger its apparent vitality. And the foundation of a constitution in a country that sways under the corrosive and denigrating influences of a foreign legation must be even more fragile.’ The Bolivian government faced a clear choice: ‘Either maintain the principle of the liberties granted by the constitution, or give in to the orders from Berlin as interpreted by the Nazi agents in La Paz.’Footnote 123 Even the conservative newspaper La Calle argued that because ‘we live in a democratic country, protecting the liberties to express an opinion, to think, and to look, one cannot justify denying the Bolivian people the right to view this work of democratic propaganda that will contribute unquestionably to strengthening the democratic sentiments of the public’.Footnote 124 The British minister planned a private showing for Bolivian officials, including President Enrique Peñaranda del Castillo and his cabinet.Footnote 125 When the Bolivian public first saw the film is unclear.

In Central America, two real-life dictators approved The Great Dictator. Despite General Jorge Ubico's pro-United States policies in Guatemala, including support for the multi-tentacled United Fruit Company, an embassy note reported, ‘There is apparently still considerable wonderment in Guatemalan circles that the Government permitted the film to be shown.’ With no allusion to Roosevelt's recent third inauguration, the official reported impassively that Guatemala's ‘experience with dictators is somewhat greater and more actual than that in the United States’.Footnote 126 With a heavy police presence on hand for the first showing, crowds sold out Guatemala City's largest theatre and partly filled another. One embassy official credited the film's popularity with ‘enormous advance enthusiasm’ and ‘the public's fear that it will be later banned’.Footnote 127 The embassy reported that ‘not even any hissing or booing’ marred the showing. Rather, ‘the audience, if moderately decorous, showed that it thoroughly enjoyed the picture’.Footnote 128 The embassy requested that the film be sent from Panama for Ubico to view it.Footnote 129 In Nicaragua, Somoza García, the first in a ruthless family dynasty that ruled for more than four decades, touted his pro-Chaplin decision as evidence of his political enlightenment: ‘We are in a democratic country. We are all democrats here. We have majority rule and if this picture is propaganda for the democracies it will be shown.’Footnote 130 In this case, a Hollywood film mediated a dictator's desired public image.

Intrigue followed the picture more than a year after its arrival in Latin America. In Paraguay, President Higinio Morínigo's dictatorship was openly pro-Axis and did not declare war on Germany until February 1945.Footnote 131 In April 1942, five bandits in search of The Great Dictator stole the wrong picture from a man leaving a train station in what was called the ‘the first assault by masked men in modern Paraguayan history’. Days later, a Russian watchman and his Bolivian assistant were posting advertisements for the film after midnight near the Granados theatre in Asunción when two men forced them into a car. Several miles outside the city, the strangers ordered the theatre employees out at gunpoint and ‘tried to force the watchman to tell him where the film The Great Dictator was kept’. When he refused, the men took his keys and drove away. Officials later found the theatre office ‘littered with films that had been taken out of their containers and examined’. After discovering the picture in canisters in a cupboard apart from the others and disguised under a different label, the thieves left a note signed by a nationalist group: ‘If you try to show the film again, we will burn the theater. Paraguay is not an American colony.’Footnote 132 United Artists arranged for a replacement copy to be flown from Lima to Asunción.Footnote 133 After a private showing for Morínigo and several hundred political and military officials a few weeks later, a US diplomat appeared relieved to report that ‘at least they were amused instead of annoyed’.Footnote 134

Despite its powerful pro-democracy message, the film could be received either as isolationist or interventionist at a moment when the United States itself was still neutral. Concerned about alienating potential allies and even embarrassing local governments, US diplomats promoted the film largely through unofficial channels. In one instance, an official in Argentina hoped demand for Chaplin would obviate the need for a diplomatic response that might create the impression that authorities ‘had given way under pressure of the United States Government rather than on their own initiative’.Footnote 135 Some embassy officials recognised that the movie was counterproductive. With great delicacy, a diplomat in Guatemala admitted that other motion pictures were ‘much less direct in their propaganda’ and enjoyed greater ‘artistic merit’.Footnote 136 Given the unique contexts in which the Chaplin film arrived, controlling the picture's meaning and reception proved impossible on all sides.

Conclusions: The Tramp and the Führer

The Great Dictator appeared in Latin America as something of an anti-Good Neighbour cultural and political product – a brash, divisive and polemical film that thwarted control on both sides of the Río Grande. This complex movie was irreducible to Hollywood entertainment, US hegemony, wartime propaganda and Chaplin slapstick. The diverse and compelling ways in which the movie surfaced in nation-state archives and the public record chart a remarkable circulation and reception that illuminate not only the role that culture plays in US power and Latin American resistance more broadly, but how diverse audiences have imagined their engagement with Hollywood stars.Footnote 137 The film did not provoke a unified response even within the confines of the theatre, much less in congressional halls, newspaper pages, diplomatic conversations, political meetings or police departments.

Thanks in part to its electrifying Latin American reception, the film grossed US$ 5 million even though it was banned in German-occupied France, where Chaplin usually played well.Footnote 138 The movie proved so memorable that Oakie later marvelled that despite making more than 100 films, what he was most remembered for was his role as Benzino Napaloni: ‘Why, even on my last trip to Mexico, the people greeted me at the plane with the Fascist salute.’Footnote 139 The film worked its way into popular culture in other ways as well. Mexican artist Diego Rivera incorporated a Chaplin image – depicting Hitler, Mussolini and Stalin above an iconic image of the moustachioed Chaplin in street clothes – in a massive San Francisco mural now known as Pan American Unity (1940).Footnote 140 Rivera later called the scene a ‘tragicomic grouping’ that ‘dramatized the fight between democracies and the totalitarian powers’.Footnote 141 The image of Chaplin without uniform, alone and vulnerable beneath the triumvirate of dictators, underscored the boldness of the film project and the power of a lone voice against authoritarianism.

Nonetheless, even Chaplin later admitted that the comedic treatment of horrific world events proved risky: ‘Had I known of the actual horrors of the German concentration camps, I could not have made The Great Dictator; I could not have made fun of the homicidal insanity of the Nazis. However, I was determined to ridicule their mystic bilge about a pure-blooded race.’Footnote 142 So powerful was Chaplin's portrayal of Hitler that the film blurred the lines between the real and the fictional. When a new photograph of Hitler emerged in 1943, the New York Times interpreted the German leader's countenance through a Chaplin lens and saw a regime in distress. Whereas Hitler's face once had ‘poise’, it was now ‘closer than ever to the Chaplin portrayal of a dictator. It is clownish. … The jaws are sagging. The eyes pouchy. The double chin more pronounced. This is not the picture of a self-assured victor. This is the portrait of a man in despair.’Footnote 143 Similarly, the German legation in Colombia employed a Chaplin photo on a bulletin that criticised Roosevelt, arguing that ‘the role of the dictator in Chaplin's film will fit Mr. Roosevelt well if Congress gives him the power he seeks’. The identification of the Tramp with the Führer appeared complete.Footnote 144

As an object and signifier to be stolen, ridiculed, celebrated, tear-gassed, locked in a bank vault and Nazi-saluted, the film participated in a curious moment when Latin Americans of many ideological persuasions attempted to assert political and cultural sovereignty. Debates over the picture divulged the extent to which Latin American governments found themselves wedged between Washington and the Old World on the eve of yet another world war. Indeed, nation-states still grappling with enduring colonial legacies have neither found nor sought a single pull-down menu of ‘Western’ options.Footnote 145 In the process, the movie previewed ideological battles to come, when Latin Americans continued to resist the United States’ gravitational pull, assert their own identity and pursue alternative paths.