Ethnic cleavages have become increasingly important in Peruvian electoral politics.Footnote 1 In the last decade, a growing gap has emerged in the voting patterns of indigenous and non-indigenous areas. This gap, which was first noticeable during the 1990 run-off election between Alberto Fujimori and Mario Vargas Llosa, resurfaced in the 2000 and 2001 elections and grew even wider in the 2006 elections. Whereas indigenous areas voted heavily for Alejandro Toledo in 2001 and Ollanta Humala in 2006, non-indigenous areas voted predominantly for Alan Garcia and Lourdes Flores in these years.Footnote 2

This gap is puzzling considering that Peru, unlike Bolivia and Ecuador, has no national-level indigenous parties, nor has any major presidential candidate self-identified as indigenous.Footnote 3 What, then, led to the emergence of an ethnic voting gap? Why did indigenous people vote en masse for certain parties and candidates that had not even identified as indigenous?

This article maintains that the ethnic voting gap developed because Peruvian politicians successfully wooed indigenous voters with a combination of ethnic and populist appeals. Fujimori, Toledo and Humala reached out to indigenous voters by recruiting indigenous candidates, invoking indigenous symbols and embracing indigenous demands. Although none of the three self-identified as indigenous, they presented themselves as more ethnically proximate to the indigenous population than their main competitors, who represented the white Lima elite. Thus, ethnic appeals formed an important part of their efforts to win indigenous support.

Populist appeals were even more fundamental to their efforts to attract indigenous voters, however. Fujimori, Toledo and Humala denounced the traditional parties and political elites, focused their campaigns and proposals on the poor and emphasised their own personal achievements and popular origins. These appeals resonated especially well with indigenous voters because they are disproportionately poor and politically disenchanted, and have only weak attachments to the existing parties.

Ethno-populist appeals have been used quite successfully in election campaigns in Bolivia and Ecuador as well.Footnote 4 The main difference, however, is that in Peru politicians have relied more on populist appeals and less on ethnic appeals. Moreover, such appeals have been made not by indigenous leaders based in powerful indigenous movements, but rather by ethnic and political outsiders heading personalist movements. As the conclusion discusses, the more populist approach taken in Peru has led to greater electoral volatility than in neighbouring countries.

This article unfolds as follows. The first section discusses Peru's ethnic makeup and the emergence of an ethnic voting gap there. The second section examines existing theories of ethnic voting and lays out the main argument. It contends that Fujimori, Toledo and Humala won the support of indigenous voters by appealing to them as indigenous people, but also as poor and politically disenchanted citizens. The next three sections examine in more detail the various ethnic and populist appeals employed by these three presidential candidates. It shows how these appeals helped each of them win the support of indigenous as well as non-indigenous voters. The sixth section briefly discusses how regional movements have used ethno-populist appeals in local elections. The conclusion examines the impact of ethno-populist linkages on electoral stability in Peru.

Ethnicity and the Ethnic Voting Gap in Peru

Peru has a large population of indigenous descent, but most do not self-identify as ‘Indian’ or ‘indigenous’ because of the social stigma attached to these terms. Moreover, the state has traditionally discouraged indigenous people from identifying as such. For example, the administration of Juan Velasco Alvarado led a campaign to recast highland Indians as peasants in the official discourse. In spite of these pressures, many indigenous people have continued to identify with indigenous ethno-linguistic categories, such as Quechua or Aymara, although they do not refer to themselves as Indians or indigenous per se.Footnote 5 The 2006 census found that 22.5 per cent of the population above 12 years of age considered themselves of Quechua origin, 2.7 per cent considered themselves Aymara, and 1.7 per cent identified with some Amazonian indigenous group.Footnote 6 The majority of Peruvians identify as mestizo – in the 2006 census, 57.6 per cent of the population self-identified as such – but there is a great deal of variance within this category.Footnote 7 Some mestizos have a mostly European appearance and few, if any, ties to indigenous culture, but many people who self-identify as mestizo appear indigenous, speak indigenous languages and/or practice indigenous customs. These people have been referred to by some academics as indigenous mestizos, but they are often popularly referred to as cholos.Footnote 8

Mestizaje or racial/ethnic mixing has blurred the boundaries between groups and created considerable ethnic ambiguity in Peru, but it has not eliminated ethnic inequalities and discrimination. Indigenous people tend to be much poorer and less well educated than their white and mestizo counterparts, and suffer from a great deal of social prejudice. Various surveys have found that Peruvians who speak indigenous languages are more likely to report having personally experienced discrimination and to believe that ethnic discrimination is widespread.Footnote 9 A 2001 survey found that 63.8 per cent of indigenous households fell below the poverty line, as opposed to 42 per cent of non-indigenous households.Footnote 10 Indigenous people have also traditionally been politically marginalised. Most of the indigenous population lives in the highlands, far from the political and economic centre of the country, and indigenous people have occupied relatively few positions of power. The economic, political and social exclusion of the indigenous population has created some ethnic resentment toward the dominant white and mestizo elites, which has been compounded by regional tensions.

Although the indigenous population has long suffered from economic, social and political exclusion, ethnic voting in Peru is a relatively recent phenomenon. Until the 1980s, most of the indigenous population could not vote because of the literacy requirements that had been imposed in 1896 after the War of the Pacific.Footnote 11 It was only after the 1978 Constitution granted suffrage to illiterates that the indigenous population became an important part of the electorate. In the wake of this reform, which also lowered the voting age from 21 to 18, voter turnout in indigenous areas soared. The number of votes cast in majority indigenous provinces rose by an average of 145 per cent between the 1978 constituent assembly elections, which were the last elections to have literacy restrictions, and the 1980 presidential elections.

As the number of indigenous voters increased, the main parties, such as the Partido Aprista Peruano (Peruvian Aprista Party, commonly known as APRA), Acción Popular (Popular Action, AP) and the Partido Popular Cristiano (Christian People's Party, PPC), began to woo them more aggressively, but did so largely through class-based, clientelist or personalist appeals. Ethnic issues such as indigenous land and water rights, affirmative action programmes and bilingual education were largely absent from the programmes and agendas of the main parties.Footnote 12 Indeed, in line with the predominant political discourse of the time, these parties generally avoided the use of the terms ‘Indian’ and ‘indigenous’ altogether; they referred to the indigenous population exclusively as ‘peasants’ and sought to appeal to them as such. Furthermore, the national parties, which were typically based in Lima, recruited few people with indigenous backgrounds as candidates or for internal leadership positions. Less than 5 per cent of congressional representatives and less than 10 per cent of provincial mayors had indigenous last names during the 1980s.Footnote 13

Leftist parties, which had a long tradition of organising in the highlands, did make some ethnic appeals during this period. They recruited some people of indigenous extraction as candidates and maintained close ties to some indigenous and peasant organisations. Nevertheless, the vast majority of the party leaders were white or mestizo, and the parties focused principally on class-based rather than ethnic appeals. Moreover, the Peruvian Left began to disintegrate in the late 1980s, leaving its many indigenous supporters up for grabs.Footnote 14

During the 1980s, voting patterns in indigenous areas resembled those of non-indigenous areas, with some modest differences. Leftist parties performed somewhat better in indigenous areas during the 1980s, but their support in majority indigenous provinces exceeded their support in minority indigenous provinces by less than 10 percentage points. The winner of the 1980 elections, Acción Popular, fared some 7 percentage points better in majority indigenous provinces, and the winner of the 1985 elections, APRA, won 12 percentage points fewer votes in majority indigenous provinces than in minority indigenous provinces. Nevertheless, in both 1980 and 1985, the party that won the most votes in indigenous areas also won the most votes in non-indigenous areas.

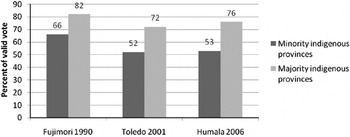

The ethnic voting gap widened somewhat in the 1990 run-off elections, when Alberto Fujimori won on average 16 percentage points more votes in majority indigenous provinces. As Figures 1 and 2 indicate, the ethnic voting gap closed subsequently, but it emerged with even more force in the 2001 elections. In these elections, Alejandro Toledo fared better in indigenous provinces by 17 percentage points in the first round and 20 percentage points in the second round. Similarly, in the 2006 elections, Ollanta Humala earned 23 percentage points more votes in majority indigenous provinces than in minority indigenous provinces during both the first and second rounds.

Figure 1. Mean Provincial Vote in First Round of Peruvian Presidential Elections, 1990–2006

Figure 2. Mean Provincial Vote in Second Round of Peruvian Presidential Elections, 1990–2006

The existence of a large voting gap between indigenous and non-indigenous areas in recent elections is surprising considering that Peru, in marked contrast to Bolivia and Ecuador, has neither a powerful indigenous movement nor an important indigenous party.Footnote 15 The Peruvian indigenous movement is fragmented into numerous organisations, none of which has a strong presence throughout the country. It is particularly weak in the highlands, where the vast majority of the indigenous population live.Footnote 16 The oldest and largest peasant grouping operating in the highlands is the Confederación Campesina del Perú (Peasant Confederation of Peru, CCP), founded in 1947.Footnote 17 This group has styled itself as a peasant, rather than an indigenous, organisation; it has traditionally refrained from advocating ethnic demands, though it has embraced some of them in recent years. The CCP, which had close ties to a variety of leftist parties, participated actively in the numerous peasant mobilisations that occurred in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, but it lost impetus from the 1980s onwards, in part because its leaders were targeted both by Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path, SL) and by the military.Footnote 18 The CCP currently claims to have 19 departmental federations along with a number of sectoral federations, but it has an important presence only in the southern highlands and its membership base is quite limited. According to the Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (National Institute of Statistics and Informatics, INEI), only 10,215 people claimed to be affiliated with the CCP in the 1994 agricultural census, out of the more than 1.75 million agricultural producers surveyed.Footnote 19

Scholars have attributed the weakness of the Peruvian indigenous movement to a wide variety of factors. These include the devastating guerrilla war waged in the highlands by SL in the 1980s and early 1990s; the Peruvian Left's hesitance to embrace ethnic issues; the dearth of prominent indigenous intellectuals; the reluctance of Peruvians of indigenous descent to self-identify as indigenous; and the fact that the economic and political centre of the country is located far away from where most of the indigenous population live.Footnote 20

Whatever the causes, the weakness and fragmentation of the Peruvian indigenous movement have impeded it from founding a national indigenous party. It has limited access to the national media, only minimal material resources and no national network of activists, nor does it have much organisational legitimacy or even name recognition to lend to a party. Thus, although the Peruvian indigenous movement has grown in recent years, it still lacks the organisational resources that enabled its counterparts in Bolivia and Ecuador to create parties that could compete on the national level.Footnote 21 As we shall see, however, indigenous voters have engaged in ethnic voting even in the absence of an indigenous party.

Explaining Ethnic Voting in Peru

Studies of ethnic voting tend to define it as the propensity of people from a particular ethnic group to vote en masse for candidates or parties identified with their group. According to Horowitz, ethnic voting means ‘simply voting for the party identified with the voter's own ethnic group, no matter who the individual candidates happen to be’.Footnote 22 Wolfinger provides a somewhat broader definition, writing that ethnic voting is ‘manifested in the tendency for members of a particular ethnic group to support one party or the other, and in the tendency for some members of an ethnic group to cross party lines to vote for a fellow ethnic’.Footnote 23

Why do people engage in ethnic voting? The literature on this topic presents two main explanations. The first approach suggests that people vote for parties or members of their own ethnic group as an expression of ethnic solidarity.Footnote 24 Horowitz, for example, grounds his explanation for ethnic politics in social identity theory, which argues that people tend to form in-groups often on the basis of trivial differences.Footnote 25 As various experiments have shown, individuals will demonstrate favouritism toward the members that they identify as being part of the in-group.Footnote 26 From this perspective, ethnic voting is not a rational weighing of alternatives, but rather a statement of allegiance toward group members.

The second explanation for ethnic voting focuses on similarities in policy preferences among members of the same ethnic group. This approach maintains that members of the same ethnic group prefer the same parties and candidates not out of ethnic solidarity, but rather because they have similar ideological preferences. Indeed, some studies have found that racially polarised voting behaviour in the United States is principally a result of variance in policy preferences across racial groups.Footnote 27 A variant of this approach suggests that race or ethnicity provides an informational shortcut.Footnote 28 People who lack information about the policies of parties or candidates will vote for the candidates or the parties that identify with their group because they assume that such candidates and parties will have policy preferences similar to their own.

These definitions overlook two other types of ethnic voting that have particular relevance for the Peruvian case, however. These are particularly likely to occur where people do not have the option of voting for a party or candidate identified with their own ethnic group or where they believe that the party or candidate belonging to their ethnic group has little chance of winning or gaining representation. Firstly, ethnic voting may consist not only of voting for a candidate or party of one's own ethnic group, but also of voting against a candidate or party that is identified with a resented ethic group. Some people's voting choices are motivated more by prejudice against, or hostility toward, other ethnic groups than by pride in their own group. Various studies in the United States have found that racial prejudice has motivated the candidate evaluations and voting decisions of white voters.Footnote 29 Even policy-motivated voters may vote against candidates or parties of resented ethnic groups since these candidates or parties may have, or be assumed to have, different policy preferences.

Secondly, ethnic voting may consist of citizens voting in large numbers for a candidate or party identified with a group that is ethnically proximate to their own group. Ethnically proximate groups share certain phenotypes or have a similar language, religion or culture. These cultural and phenotypical similarities may lead voters to identify with, and feel a sense of ethnic solidarity with, candidates or parties from ethnically proximate groups. Of course, ethnic proximity does not always lead to ethnic or political solidarity. In some cases, high levels of antagonism exist between ethnically proximate groups, such as was experienced by Serbs and Croats in the wake of the dissolution of the former Yugoslavia. The argument here is only that voters are more likely to feel ethnic solidarity towards ethnically proximate groups, not that they will always do so. Although one would expect voters to have lower levels of ethnic attachment to candidates and parties of proximate ethnic groups than to their own ethnic group, we would still expect them to feel a greater sense of ethnic solidarity with proximate ethnic groups than with distant ones. In addition, people might also be more likely to vote for parties or candidates of ethnically proximate groups because they know or assume that these parties or candidates have policy positions closer to their own preferences than do the parties or candidates identified with ethnically distant groups.Footnote 30

Ethnic voting in Peru has taken both of these forms. Indigenous voters have voted against candidates and parties of the white/mestizo coastal elite, towards whom they have felt a certain degree of ethnic resentment or hostility. They also have voted for the candidates of ethnically proximate groups, especially dark-skinned cholo or mestizo candidates of indigenous descent. Such ethnic voting should not be equated simply with a preference for outsider candidates. Although the main beneficiaries in recent years have been political outsiders, they have not been the only ones to compete in these elections. Toledo and Humala emerged from the long list of outsider candidates and fared well in indigenous areas in part because of their ethnic proximity to the indigenous population. Indeed, as the analysis of the vote for Humala in 2006 indicates, indigenous people were more likely to vote for Humala even controlling for disenchantment with the existing parties and other characteristics associated with support for outsider candidates.

Why have indigenous voters in Peru engaged in these types of ethnic voting? To begin with, indigenous voters have identified more with dark-skinned cholo or mestizo candidates than with their principal opponents who hailed from the light-skinned Lima elite. Indigenous voters have not had the opportunity to vote for indigenous candidates or parties in presidential elections, but they have been able to vote for candidates from ethnically proximate groups. Moreover, these candidates have sought to enhance their attractiveness to indigenous voters by making direct ethnic appeals.Footnote 31 They have recruited numerous indigenous candidates, formed alliances with indigenous and peasant groups, incorporated indigenous symbols into their campaigns and embraced numerous indigenous demands. These ethnic appeals have resonated with many indigenous voters and helped contribute to the strong performance of these candidates in indigenous areas.

In the 2000 and especially the 2001 presidential elections, the indigenous population voted predominantly for Alejandro Toledo, a Peruvian economist with strongly indigenous features. Toledo presented himself as a cholo and campaigned extensively in indigenous and cholo areas. According to Eliane Karp, Toledo's wife, the relationship between Toledo and the electorate was ‘love at first sight. I can't deny that there is an ethnic factor, a powerful identification [with him]’.Footnote 32 Similarly, in the 2006 elections, the indigenous population voted overwhelmingly for Ollanta Humala, a candidate with a Quechua name and background. Humala did not self-identify as indigenous or cholo, but his name, appearance and family background conveyed his Andean origins. Both Toledo and Humala were clearly ethnically more proximate to the indigenous population than either Alan García or Lourdes Flores, their main competitors in the 2001 and 2006 elections. García and Flores are both light-skinned and hail from the coast, and, partly as a result, they found only limited support in indigenous areas.

The case of Alberto Fujimori is somewhat more complicated. Fujimori is of Japanese origin and is therefore not in an ethnic group that one would normally think of as ethnically proximate to the indigenous population. Nevertheless, in the 1990 presidential run-off elections he was able to win a disproportionate percentage of the indigenous vote. This outcome can be understood in part by reference to his opponent in the 1990 run-off, Mario Vargas Llosa, who symbolised the white Lima upper crust.Footnote 33 In the 1990 campaign, Vargas Llosa's supporters, including his spokesperson, questioned how someone of Japanese descent whose parents were not born in Peru could become president.Footnote 34 As an immigrant, an ethnic minority and an outsider, however, Fujimori had more in common than did Vargas Llosa with the indigenous people in the highlands and the cholo migrants who populated the poor neighbourhoods in the cities.Footnote 35 Fujimori's campaign slogan, ‘A president like you’, took advantage of this, effectively contrasting him with the wealthy, fair-skinned and aristocratic Vargas Llosa.Footnote 36

Indigenous voters opted for Humala, Toledo and Fujimori not just because they identified with them and their ethnic appeals, but, even more importantly, because they sympathised with their populist rhetoric and policy proposals. Indeed, populist appeals were a much more central part of these candidates’ campaigns than were ethnic appeals. The exact nature of these appeals varied considerably, with Fujimori and Toledo opting for a kind of neoliberal populism and Humala for a more traditional nationalist and state interventionist brand of populism. Nevertheless, all of their campaigns contained three core elements of populism: (1) personalistic leadership; (2) a focus on the lower classes; and (3) extensive anti-establishment rhetoric. All developed their own electoral vehicles and centred the campaigns on their own biographies. They each emphasised their popular origins and directed many of their appeals at the lower classes, and they all virulently denounced the traditional parties and elites.

These populist appeals resonated with many Peruvian voters because of their continued poverty and growing disenchantment with the traditional parties and political elites. Indigenous people in particular were receptive to these appeals because they tend to be much poorer than non-indigenous people. Indigenous people also have become particularly disenchanted with the traditional parties and the political system more generally. In a 2006 survey by the Latin American Public Opinion Project, 72.4 per cent of indigenous language speakers reported that they had little or no trust in political parties, as opposed to 58.9 per cent of people who did not speak an indigenous language.Footnote 37 Similarly, 73.3 per cent of indigenous language speakers reported that they were dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with the way democracy functions in Peru, as opposed to 58.6 per cent of non-indigenous language speakers.

Thus, the recent ethnic voting gap in Peru can be explained in large part by the ethnic identities of recent presidential candidates and the ethno-populist appeals that they employed in their campaigns. Humala, Toledo and Fujimori attracted indigenous voters not only because they were more ethnically proximate to those voters than were their main competitors, but also because their ethno-populist rhetoric and proposals resonated with many indigenous people. In the following pages, I explore these arguments in more detail. I focus to a certain degree on the second round of the elections because ethnic appeals were used more widely and the ethnic contrasts between the candidates were more apparent in the second round. That said, Humala and Toledo also made ethnic appeals during the first rounds of the 2001 and 2006 elections, and ethnic proximity helps explain the large voting gap that occurred in both the first and second rounds of these elections.

Fujimori and the Indigenous Vote

It was not until the 1990 campaign of Alberto Fujimori that ethnicity became a major issue in a presidential election. Although Fujimori largely eschewed explicit ethnic appeals, he benefited from and exploited Peru's ethnic divides.Footnote 38 Not only did Fujimori contrast his own ethnic origins to those of Vargas Llosa, but he also recruited many more indigenous and cholo candidates than the traditional parties had typically included. Indeed, Fujimori described the 1990 campaign as a contest between ‘blanquitos’ and ‘un chinito y cuatro cholitos’.Footnote 39 Moreover, some of these indigenous people and cholos occupied important places on the ballot. For example, Fujimori's first vice-president, Máximo San Román, was a successful, dark-skinned, Quechua-speaking entrepreneur from Cusco, and Fujimori used him extensively in his campaign.

Fujimori used populist appeals even more extensively than ethnic appeals, however. His campaigns focused mostly on him rather than on his party or platform. Indeed, in 1990, he barely cobbled together a party in time to compete in the elections, and even then he did not put together a detailed governing plan or a complete slate of candidates. He railed against the traditional parties and elites, using his dearth of ties to the traditional parties and his lack of political experience to position himself as a political outsider. He sought to portray himself as a man of the people, and surrounded himself with individuals who represented the lower classes and politically and economically marginalised regions. He campaigned extensively in poorer areas and put forward policies specifically designed to benefit poorer Peruvians, such as proposals to legalise street vendors and to create a bank to lend to businesses in the informal sector.Footnote 40 That said, Fujimori generally avoided classical economic populist appeals. During the 1990 campaign he criticised Vargas Llosa's plans to carry out radical economic shock therapy and he proposed some spending programmes, but he was vague about what his own economic policies would be. Moreover, once in office Fujimori adopted a sweeping market-oriented reform agenda that went well beyond what Vargas Llosa had proposed to do.

Ultimately, Fujimori's ethno-populist appeals paid off. The 1990 election was largely a clash over personalities, and in one survey that year almost two-thirds of voters mentioned candidate characteristics as the key factor determining their vote, as opposed to only 28 per cent who mentioned programmes or ideology.Footnote 41 Fujimori's decision to focus his campaign on his personal characteristics was thus politically fruitful. Indeed, the specific qualities that Fujimori emphasised – honesty, education, and identification with the people – were among those that Peruvians had cited in surveys as being the most important for a politician.Footnote 42 In particular, many Peruvians supported Fujimori because they saw him as ‘closer to the popular classes’, in the words of one worker.Footnote 43 Fujimori also benefited from his lack of ties to the traditional parties. By 1990 public opinion had turned heavily against the political establishment after the disastrous administrations of Alan García and Fernando Belaúnde, which had left the economy in ruins and the country in the midst of a violent guerrilla war. According to one survey, more than 50 per cent of those people who reported voting for Fujimori in the 1990 elections stated that they chose him because of his political independence.Footnote 44

Fujimori's ethno-populist appeals resonated particularly well in indigenous areas, as Figures 1 and 2 show. Indeed, during the second round of the 1990 elections he won an astonishing 81.5 per cent of the vote in provinces where the majority of the population grew up speaking an indigenous language.Footnote 45 Moreover, as Table 1 indicates, the proportion of the population that grew up speaking an indigenous language had a statistically significant positive impact on Fujimori's share of the provincial vote in the 1990 elections, even controlling for the size of the poor population in each province.Footnote 46

Table 1. Correlates of Provincial Vote Share for Selected Peruvian Presidential Candidates, 1990–2006 (OLS Regression Models)

Note: standard errors in parentheses.

* p < .05

** p< .01

*** p< .001

Fujimori continued to make ethno-populist appeals in his subsequent campaigns. As president, he often donned a poncho and visited rural highland communities to inaugurate public works.Footnote 47 He railed against the political establishment even after becoming president, and in 1992 he went so far as to carry out an autogolpe, closing congress and suspending the constitution. After 1990, however, Fujimori's electoral success was based in large part on evaluations of his performance in office rather than his ethnic or populist appeals. Fujimori triumphed in 1995, for example, largely because of his success in overcoming the economic crisis and defeating SL.Footnote 48 By 1993 inflation had declined to 48.6 per cent, down from 7,481 per cent in 1990, and the economy had begun to grow at a rapid pace, which it would maintain throughout the mid-1990s.Footnote 49 Meanwhile, the capture in 1992 of the leader of SL, Abimael Guzmán, led to the gradual disintegration of that guerrilla movement. The number of deaths caused by political violence declined from 3,590 in 1984 to 83 in 1998.Footnote 50

Fujimori's electoral base, which was already fairly heterogeneous in 1990, became even more so in subsequent years, as he won broad support among the wealthier and whiter sectors of the population that had supported Vargas Llosa in 1990.Footnote 51 Fujimori remained quite popular in indigenous and poor areas, but he did not fare appreciably better in these areas than in others, as Figures 1 and 2 illustrate. In fact, Fujimori actually fared worse in majority indigenous provinces than in minority indigenous provinces in the 2000 elections, when he faced stiff competition for the indigenous vote from Alejandro Toledo. Moreover, as Table 1 shows, once we control for the size of the poor population in each province, the proportion of the provincial population that grew up speaking an indigenous language had no significant impact on Fujimori's share of the vote in the 1995 and 2000 elections.

Toledo's Cholo Power

In the 2000 elections, it was Alejandro Toledo rather than Fujimori who made his own ethnicity central to his campaigns. Toledo had first used ethnic rhetoric during his unsuccessful 1994–5 campaign for president, pronouncing at one point that ‘I am a symbol of every one of you … we are not going to lose this opportunity for the cholos. Our turn has arrived, that is not anti-anybody, but rather pro-us’.Footnote 52 He continued to present himself as a cholo during his 2000 and 2001 presidential campaigns, and crowds at his 2000 rallies would often chant ‘¡Cholo sí, Chino no!’.Footnote 53 Toledo also invoked numerous indigenous symbols, wearing indigenous clothing, using the chakana, an Incan cross, as the party's logo, and referring to himself as Pachacútec.Footnote 54 After the 2001 election, he even held an inauguration ceremony at Machu Picchu, which included some traditional indigenous ceremonies and symbols. Throughout the campaigns Toledo's Belgian wife, Eliane Karp, also made ethnic appeals, at times in Quechua, on Toledo's behalf.

Toledo also reached out to indigenous and peasant leaders. He formed alliances with a number of peasant and indigenous organisations, including the Confederación Campesina del Perú (Peasants Confederation of Peru, CCP). The CCP participated to such an extent in Toledo's electoral campaign that one of its leaders referred to it as Toledo's ‘fundamental base’.Footnote 55 In addition, Toledo recruited numerous indigenous and cholo candidates – according to Paredes, 21 per cent of the candidates and 38 per cent of those people who were elected to congress from Toledo's party, Perú Posible, had indigenous surnames.Footnote 56 This represented an impressive 70 per cent of the total number of members of congress with indigenous names during the 2001–6 legislative session. Perhaps the most prominent indigenous leader affiliated with Toledo's campaign was Paulina Arpasi, the Aymara-speaking secretary-general of the CCP from the department of Puno. After she was elected to congress, Arpasi, presented herself as the legislature's representative of indigenous people, stating: ‘I think it is not only necessary that indígenas know that they have a representative in the National Congress, it is also very important that the National Congress knows that it has within it a representative of the indígenas. I will change neither my indigenous dress, nor my constant defence of the rights of the indigenous peoples of Peru’.Footnote 57

Like Fujimori, however, Toledo depended more on populist than ethnic appeals. He came from a poor highland family and had worked as a shepherd and a shoeshine boy before winning a scholarship to attend college in the United States and eventually earning a doctorate in educational economics from Stanford University. His campaigns focused mostly on his accomplishments and emphasised his humble origins and his compelling rags-to-riches story. He presented himself as a political outsider and denounced the political establishment in scathing terms. In Toledo's case, however, the corrupt establishment that he railed against was not the traditional parties but Fujimori's government.Footnote 58

Most of Toledo's energy was focused on winning the support of the poor. He campaigned extensively in the poorer neighbourhoods of Lima and he used his relaxed, down-to-earth style to establish a rapport with poorer Peruvians. Toledo declared that he would be the president of the poor and unveiled numerous social programmes designed to help them. For example, he promised to supply health insurance to poor women and children, to create an agricultural bank to provide loans to small farmers, and to improve the sanitation of shanty towns in Lima.Footnote 59 Nevertheless, Toledo was more of a neoliberal populist than a classical populist. At times he did engage in economic populism on the campaign trail, promising to create a million jobs and to boost the salaries of teachers, health workers, police officers and other government employees,Footnote 60 but for the most part he supported the broad outlines of Fujimori's economic model, even as he promised to put a human face on market policies.

Toledo first ran for president in 1995, but Fujimori was enormously popular at the time. As a result, the former's candidacy gained little traction, and he finished with only 3.2 per cent of the national vote. In the late 1990s, however, Fujimori's popularity ebbed somewhat because of growing economic problems and the government's involvement in various political scandals.Footnote 61 Nevertheless, he remained popular among some sectors of the electorate, particularly the poor, in large part because of his earlier political and economic achievements and his considerable spending programmes. This reservoir of support, along with his control of the state, helped him prevail in a closely contested battle. According to the official returns, he captured 49.9 per cent of the valid vote in the first round of the presidential elections, while Toledo won 40.2 percent, although Toledo and many independent observers argued that the Fujimori administration had committed fraud.Footnote 62 The electoral authorities nevertheless certified the results, forcing a run-off election since neither candidate had won 50 per cent of the vote. Ten days before the run-off election, however, Toledo withdrew on the grounds that the Fujimori administration had refused to put into place the necessary mechanisms to prevent a repeat of the voter fraud.

Toledo ran again for president in 2001 after Fujimori's resignation in the wake of various corruption scandals. This time he won the first round of the elections with 36.5 per cent of the vote, in spite of a number of personal scandals of his own. Alan García of APRA came in a surprising second place with 25.8 per cent of the vote, just ahead of the conservative candidate, Lourdes Flores of Unidad Nacional. García was thought to be a weak opponent because of his disastrous previous administration as president (1985–90), but he was an effective campaigner and possessed a much stronger party organisation than did Toledo. Nevertheless, Toledo managed to win in the second round with 53.1 per cent of the vote.

Toledo's populist appeals helped him considerably in both 2000 and 2001. According to an Apoyo survey of the 2000 elections, most voters who supported Toledo cited his personal characteristics, rather than his ideology or party programme, as their reason for voting for him in the first round.Footnote 63 Sixty per cent of his supporters cited his professional experience as an economist. Others referred to his humble origins: 26 per cent said that they voted for him because he identified with the people; 23 per cent because he rose up from poverty; and 15 per cent because he was from the provinces. The voters that did refer to his governing programme typically mentioned his populist promise to provide jobs. Voters cited similar reasons for voting for Toledo in 2001, but in that year many voters also said that they supported him because he had defeated the Fujimori dictatorship.Footnote 64

Toledo's ethnic appeals also helped him significantly in 2000 and 2001. In both elections, he fared much better in indigenous areas than in non-indigenous areas. In 2000, for example, he won 42.3 per cent of the vote in provinces where the majority of the population grew up speaking an indigenous language, whereas he won only 36.2 per cent of the vote in other provinces. He might have done even better in indigenous areas if Fujimori had not retained support among the many indigenous and poor people who had benefited from his administration's social programmes. In 2001, against weaker competition, Toledo swept indigenous areas, winning 53.9 per cent of the vote in majority indigenous provinces in the first round and 71.7 per cent of the second round vote. As Table 1 indicates, in 2000 and 2001, the percentage of the population that grew up speaking an indigenous language was a highly statistically significant determinant of his provincial vote, even controlling for the wealth of the province.

Humala's Ethno-populism

In the 2006 elections, it was a newcomer to electoral politics, Ollanta Humala, who exploited Peru's ethnic divides most successfully. Humala, who was named after the commander-in-chief of the armies of the Incan leader Pachacuti, frequently invoked traditional indigenous symbols.Footnote 65 At campaign rallies, he would sometimes don a poncho and speak phrases in Quechua. The logo of his party, the Partido Nacionalista Peruano (Peruvian Nationalist Party, PNP), was a traditional Incan clay pot, and his campaign rallies and materials often included the rainbow-coloured indigenous flag. He also sought to appeal to indigenous people by naming many people of indigenous descent as candidates for important positions. According to Paredes, 13 per cent of the 2006 congressional candidates of the alliance of the Unión por el Perú (Union for Peru, UPP) and the PNP had indigenous surnames.Footnote 66 By contrast, only 6 per cent of the candidates of APRA, the UPP-PNP's main rival in the elections, had indigenous last names. Moreover, many of these indigenous leaders occupied places high on the UPP-PNP's ticket, which enabled them to be elected to the legislature. For example, Hilaria Supa and María Sumire, two indigenous leaders from Cusco, both won seats in Congress representing Humala's ticket, as did Juana Huancahuari, a peasant leader from Ayacucho. Humala also struck an alliance with the coca growers, and two cocalera leaders, Nancy Obregón and Elsa Malpartida, were elected to the Peruvian Congress and the Andean Parliament respectively on Humala's slate. In addition, many former soldiers of indigenous descent, known as reservistas, worked as local organisers of his campaign.Footnote 67 Nevertheless, most of the party's congressional representatives as well as its overall leadership were white or mestizo.

Humala did not make ethnic demands central to his campaign, but he did include them in his discourse and platform. His governing plan, for example, called for the recognition of Peru as a multicultural country, endorsed multicultural education and the use of indigenous languages in the military and government offices, and demanded the legitimisation and incorporation of traditional practices of indigenous medicine and justice.Footnote 68 Humala also frequently denounced ethnic inequality and extolled the virtues of Peru's indigenous population. In one 2006 speech he noted that during his time in the army he never encountered soldiers with the European-origin surnames of wealthy Peruvians, but only people with indigenous names: ‘There was only Huamán, Quispe, Condori … they are the true Peruvian people’.Footnote 69

Like Fujimori and Toledo, Humala was careful to avoid exclusionary ethno-nationalist appeals. In the latter's case, however, this task was complicated by the fact that his immediate family members often engaged in ethno-nationalist rhetoric. Humala's father, Isak, had developed a radical ethno-nationalist ideology dubbed etnocacerismo, which proclaimed the superiority of what he called the ‘copper-coloured race’.Footnote 70 In an interview with the Washington Post, Isak Humala acknowledged his ethno-nationalist views: ‘We are racists, certainly. We advocate saving the copper race from extinction, disintegration and degeneration.’Footnote 71 Ollanta's brother, Antauro, sought to spread this philosophy through his organising efforts in the highlands of Peru and published various articles and books outlining his ideas. Ollanta had previously seemed to endorse this philosophy, but during the campaign he sought to distance himself from the more radical and intolerant actions and statements of his family members. Instead, he emphasised the inclusive nature of his campaign, proclaiming in his governing plan that ‘we represent a historic multicultural movement’.Footnote 72 Ollanta presented himself as a nationalist rather than an ethno-nationalist.Footnote 73 Ollanta's father and brother, meanwhile, declared their support for another brother, Ulises, who endorsed their ethno-nationalist ideology. Ulises ran for president in 2006 as the candidate of a small party, Avanza País, and Antauro ran for congress on the ticket of this same party.Footnote 74 Ulises’ ethno-nationalist rhetoric failed to resonate among Peruvian voters, however, and he won a mere 0.2 per cent of the national vote.

Humala also sought to win over voters with populist appeals, as Fujimori and Toledo had done. His campaign and party were highly personalistic, and he ran to a large extent on his own biography. A former army commander, he had first come to public attention when he, along with his brother, carried out an uprising against Fujimori during the final days of Fujimori's regime. The military quelled the uprising and imprisoned Humala, but he was freed and pardoned after Fujimori resigned. Humala thus had strong anti-establishment credentials, and he built upon these during his 2006 campaign, railing against the traditional parties, the legislature and the political class, whom he accused of corruption. He called for a constituent assembly, as in Venezuela, which would overhaul Peru's political institutions. He even proudly embraced the label of anti-system candidate, declaring: ‘If the system is corruption, the insensitivity of the political class, the turning over of the country to transnational capital, I feel proud to be anti-system’.Footnote 75

Again, akin to Fujimori and Toledo, Humala presented himself as a man of the people. He denounced the wealthy oligarchy and criticised Toledo for not doing more for the poor.Footnote 76 He proposed boosting social spending by 1 per cent of GDP in three years in order to reduce chronic malnutrition by 50 per cent, and he promised within five years to provide safe drinking water and sanitation to one million people in rural areas, and to reduce the number of people living in extreme poverty by a similar amount.Footnote 77 Humala also proposed various agricultural, employment and education programmes designed to help reduce poverty and generate sustainable development.

That said, Humala differed considerably from Fujimori and Toledo in that he was a populist in the classical mode who supported redistributive and state interventionist policies and aimed to model his government after the populist military regime of Juan Velasco Alvarado.Footnote 78 Humala frequently criticised the free-market policies of Fujimori and Toledo; indeed, the first paragraph of his governing plan declared that:

The systematic application of neoliberalism … in our country has meant a social fracture without precedents in Peruvian life. On one side there is a gigantic accumulation of wealth and power in a minority of the population, while the other side has experienced a brutal increase in social inequalities and poverty for the large majority of people excluded from the system.Footnote 79

Humala proposed a plan of state-led inward-oriented development that would help redistribute the country's wealth. He pledged to respect private property, but he argued that in some strategic areas, such as aviation and gas, there should be state participation.Footnote 80 He blamed foreign countries and companies for exploiting and impoverishing Peru, and vowed to defend the ‘national resources that this [the Toledo] government has given away to transnational companies’.Footnote 81 He pledged to re-examine Peru's foreign debt commitments as well as the foreign investments that had been made under previous governments, although he was careful to say that he did not oppose foreign investment per se.Footnote 82 He also vowed to renegotiate the free trade agreement with the United States that had been signed during the Toledo administration, and he promised to bring an end to the forced coca eradication programmes that the Peruvian government had carried out with US assistance.

Humala's ethno-populist appeals played an important role in his electoral rise. By 2006 many Peruvians had long since become disillusioned with the Toledo government, and Humala's anti-establishment credentials and vehement denunciations of the Toledo government and the traditional parties struck a chord with many voters. In an Apoyo poll taken shortly after the second round of elections, the two most common responses that supporters of Humala gave to the question of why they voted for him were that he represented a change, and that he would combat corruption.Footnote 83 He also won the support of some voters because of his identification with the masses. A post-election poll by the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú (Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, PUCP) found that voters felt he was the candidate who was closest to the poor.Footnote 84 His nationalist and state interventionist views also won him some support – for example, 18 per cent of voters in the Apoyo poll said they supported him because he was a nationalist.Footnote 85

Although Humala fared well among many categories of voters, he ultimately did not win the support of the majority. He won the first round of the elections in April 2006 with 30.6 per cent of the valid vote, finishing well ahead of Alan García who, as in 2001, narrowly edged out Lourdes Flores for second place. In the second round of the elections, however, García defeated Humala by a margin of 52.6 to 47.4 per cent. Humala swept the highlands and the Amazon, but he fared less well in Lima and the coast.

Several factors contributed to Humala's second-round defeat. First, although his stance against market reform may have helped fuel his initial rise in the polls, it hurt him in the second round of the elections. Market-oriented policies have generated greater benefits in Peru than in most other Latin American countries. Indeed, between 1991 and 2006, the national economy grew by 4.7 per cent annually, one of the fastest rates in the region. As a result, a significant proportion of Peruvians came to support market-oriented policies. According to 2006 surveys by Apoyo, 53 per cent supported the country's free trade agreement with the USA and 51 per cent opposed the nationalisation of gas companies in Peru.Footnote 86 Humala's nationalist and state interventionist appeals won him support in some sectors of the population, but they hurt him with others. In addition, he was hurt by his association with the left-wing Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez, who endorsed Humala and repeatedly denounced Alan García. According to a poll by Apoyo, the vast majority of Peruvians had an unfavourable perception of Chávez and disapproved of his intervention in the campaign.Footnote 87

Equally importantly, Humala had a number of negative characteristics as a candidate. To begin with, he was a relatively poor public speaker and debater. He was also widely perceived as authoritarian – indeed, a PUCP survey found that 42 per cent of Peruvians classified him as authoritarian and only 16 per cent classified him as democratic, which was by far the worst ratio of any of the top three candidates.Footnote 88 The media, his opponents and various NGOs accused him of committing serious human rights violations during the war against SL and of being complicit in the bloody uprising in Andahuaylas instigated by his brother. Humala's family was also a constant source of embarrassment, although he tried to distance himself from their words and actions. Ultimately, Humala was unable to overcome these obstacles in spite of the relative success of his ethno-populist appeals.

Nevertheless, Humala clearly won the support of the majority of indigenous voters. According to a 2006 survey by the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP), in the second round of the elections he won 63 per cent of the vote among self-identified indigenous people, 43 per cent of the vote among mestizos and 31 per cent of the vote among people who self-identify as white. Similarly, he won 61 per cent of the vote among people who grew up in a home where an indigenous language was spoken, as opposed to only 33 per cent of the vote among people whose parents only spoke Spanish at home. Approximately, 48 per cent of his total votes came from people who grew up in an indigenous-language-speaking household. The LAPOP data thus suggest that Humala's ethnic appeals were successful in attracting people of indigenous descent, although he was inclusive enough to win the support of a significant number of people who neither self-identified as indigenous nor grew up in a home where an indigenous language was spoken.Footnote 89 He also fared even better in indigenous areas than Toledo did – in the first round of the 2006 elections, Humala won 58.3 per cent of the vote in provinces where a majority of the population grew up speaking an indigenous language, as opposed to only 35.2 per cent in other provinces. He did even better in the second round, winning 75.7 per cent of the vote in majority indigenous provinces. As shown in Table 1, the percentage of the population that speaks an indigenous language was a statistically significant determinant of the provincial vote for Humala in both the first and second rounds, even controlling for the wealth of the provinces.

Table 2 presents the results of a logistic regression analysis of the vote for Humala in the second round using individual-level data from the LAPOP 2006 Peru survey. The coefficients represent the maximum likelihood estimates of voting for Humala over García. The results show that having an indigenous linguistic background considerably increased the likelihood of voting for Humala, even when we control for a wide range of other variables such as income, region, ideology and attitudes. The variables measuring whether an individual grew up speaking an indigenous language at home and whether an indigenous tongue was his or her first language are both positive and highly statistically significant. This suggests that Humala's ethnic appeals were successful.

Table 2. Correlates of Vote for Humala in Second Round of 2006 Presidential Elections (Logistic Regression Analysis using LAPOP 2006 Survey)

Interestingly, however, self-identifying as indigenous does not have a significant impact on the likelihood of voting for Humala once the linguistic background of the respondents and other variables are controlled for. This is undoubtedly the case in large part because 87 per cent of the Peruvians who self-identify as indigenous in the survey grew up in a home where an indigenous language was spoken. Nevertheless, it is also an indication that Humala's inclusive appeals were successful in attracting many people who do not self-identify as indigenous. Humala was particularly successful in winning the support of people who self-identify as mestizo. Indeed, the variable measuring whether the respondent is mestizo is positive and falls just short of conventional levels of statistical significance.

Table 2 also suggests that Humala's populist appeals paid dividends, helping him win the support of anti-establishment, personalist, nationalist and state interventionist voters. The variables measuring trust in parties and satisfaction with democracy are negative and statistically significant, indicating that people who have little trust in parties and little satisfaction with democracy are more likely to have voted for Humala. Similarly, the coefficient for participation in protests is positive and statistically significant. People who voted based on candidate characteristics are also more likely to have supported Humala, although this variable falls slightly under conventional levels of statistical significance. Finally, leftists, who are typically more critical of foreign intervention in Latin America and support increased state intervention in the economy, are significantly more likely to have voted for him.Footnote 90 Surprisingly, the variable measuring the income of the respondent is not statistically significant, indicating that poorer voters were not significantly more likely to have voted for Humala once we control for other variables like language and political attitudes. Perhaps most surprisingly, most of the regional variables are statistically insignificant. Ceteris paribus, people who live in the Amazon or the southern highlands are not significantly more likely to have voted for Humala once other variables like language and political attitudes are controlled for. Residents of Lima, however, are significantly less likely to have voted for Humala, whereas people who grew up in the countryside are much more likely to have done so.

On balance, the logistic regression model presented in Table 2 provides support for the argument that Humala's ethnic and populist appeals proved effective. These appeals helped him win the support of voters with indigenous backgrounds as well as personalist, anti-establishment, nationalist and state interventionist voters. Thus, like ethno-populist leaders in Bolivia and Ecuador, he managed to fuse indigenous voters to traditional populist constituencies, although their votes were ultimately not sufficient to deliver him the presidency.

Ethno-populism at the Local Level

Ethno-populist appeals have also proven effective in local elections in Peru in recent years. In the last decade, the control of provincial and municipal offices in the Andes has become increasingly important as authority has been devolved to the local level.Footnote 91 Partly as a result, numerous indigenous and peasant groups have founded their own electoral movements in an effort to win power. According to Paredes, the number of political organisations with indigenous or peasant names competing in provincial elections rose from three in 1995 to seven in 1998 and 15 in 2002, most of which were located in the southern highlands.Footnote 92 By my calculations, 14 movements with indigenous or peasant names competed in the 2006 provincial elections. These movements won an average of 14.8 per cent of the vote in the 83 provincial elections in which they competed in 2002, and an average of 19.7 per cent of the valid vote in the 59 provinces in which they competed in 2006.Footnote 93 Some of these movements have captured important municipal or regional offices ranging from mayoralties to municipal and regional councillor positions.

These movements have not campaigned on ethnic issues alone, but rather have used a combination of ethnic, personalistic, anti-establishment and class-oriented appeals to win the support of indigenous voters. In the early 1990s, the indigenous leaders of a number of peasant communities in the province of Angaraes in the southern highlands banded together with a group of unaffiliated professionals to form the Movimiento Independiente de Campesinos y Profesionales (Independent Movement of Peasants and Professionals, MINCAP). The new party, which eventually captured the mayoralty of Angaraes, developed a strong indigenista discourse but also emphasised its independence from the traditional parties and stressed that it would work on behalf of the ‘people’.Footnote 94 Another party with a marked ethnic discourse, the Alianza Electoral Frente Popular Llapanchik (Llapanchik Popular Front Electoral Alliance), emerged in the province of Andahuaylas during the early 2000s. This party embraced an indigenista discourse from the outset, but this discourse coexisted with more traditional agrarian demands. Llapanchik fared quite well in the 2002 and 2006 regional elections in Andahuaylas, and it even managed to get its candidate, David Salazar, elected regional president.Footnote 95 Finally, the coca-growers’ movement in Peru also attempted to create its own party and in alliance with a regional party it participated in the 2006 regional elections under the name of the Movimiento Independiente Qatun Tarpuy (Qatun Tarpuy Independent Movement). This alliance, which emphasised the defence of the coca leaf and, to a lesser extent, indigenous rights, finished second in the department of Ayacucho, winning a couple of provincial mayoralties and 15 district mayoralties. It fared particularly well in the coca-growing districts, where all of the mayors it elected are coca-grower leaders.Footnote 96

Thus, various indigenous and peasant groups have successfully employed ethno-populist appeals in municipal and regional elections in Peru. None of these local electoral movements have yet managed to scale up to the national level, however, in part because the Peruvian indigenous movement remains weak and fragmented.

Conclusion

This article has argued that an ethnic voting gap has emerged in Peru in part because indigenous voters have identified ethnically with Fujimori, Toledo and Humala more than with their main competitors. In addition, these three candidates wooed indigenous voters with ethnic appeals. They recruited indigenous candidates, formed alliances with indigenous organisations, invoked indigenous symbols and adopted some traditional indigenous demands.

Nevertheless, they relied less on ethnic appeals than their counterparts in Bolivia and Ecuador. Whereas Evo Morales in Bolivia and the various leaders of Pachakutik in Ecuador made ethnic appeals a central part of their campaigns, Fujimori, Toledo and Humala focused first and foremost on populist appeals. They attracted indigenous voters by denouncing the traditional parties and political elites, focusing their campaigns on the poor and presenting themselves as the saviours of Peru. These appeals resonated among many indigenous voters, who were disproportionately poor and politically disenchanted.

These populist appeals have not been conducive to electoral stability, however. Whereas ethnic linkages are known to produce stable ties to voters, populist linkages in Latin America have traditionally been associated with electoral volatility. Populist candidates who centre their campaigns around themselves often fail to invest in the institution-building efforts that are necessary for the long-term health of their parties. Indeed, as we have seen, Fujimori, Toledo and Humala have all failed to build strong party organisations. Instead, they have run personalistic campaigns and have consistently placed their own interests over those of their parties, with predictable results. Similarly, populists who utilise anti-establishment appeals to win votes typically find that these appeals become less effective once they take office. In Peru many marginalised sectors, including the indigenous population, grew increasingly disenchanted with Fujimori and Toledo over time because they held them responsible for their own and their nation's continuing problems.

Neither Fujimori, Toledo nor Humala has yet succeeded in establishing enduring ties to indigenous voters. Fujimori dominated Peruvian politics during the 1990s and won the support of a large percentage of indigenous voters during this period, but he lost the support of many of these voters in the 2000 elections. Moreover, Fujimori's party, which his daughter now leads, has won only a limited percentage of the vote in indigenous areas since that time. Toledo, meanwhile, captured much of the indigenous vote in the 2000 and 2001 elections, but his party fared poorly in indigenous as well as in non-indigenous areas in the 2006 elections, winning only 4 per cent of the valid vote nationwide. Finally, Humala dominated indigenous areas in the 2006 elections, but he has struggled to hold his party together since then. His party's alliance with the UPP has frayed, and the PNP fared poorly in the regional elections in late 2006, winning only ten provincial mayoralties and none of the regional presidencies.

The emergence of a party that is firmly rooted in a strong indigenous movement, like Bolivia's Movimiento al Socialismo (Movement Toward Socialism, MAS), might reduce this volatility by establishing enduring ethnic linkages to indigenous voters. Indeed, over the last decade the MAS has consistently won the support of indigenous voters in Bolivia. There have been discussions about creating such a party in Peru for the 2011 elections. Given the weakness and fragmentation of Peru's indigenous movement, however, it seems unlikely that any party will come to be seen as the legitimate representative of the indigenous population in the near future. As a result, indigenous voters will probably continue to shift their allegiances from election to election, leading to an unpredictable and highly volatile political environment.