Introduction

Oropharyngeal dysphagia is caused by difficulty in bolus preparation and transport from the mouth to the oesophagus, which alters the efficiency and/or the safety of swallowing. Its consequences are malnutrition and aspiration pneumonia, which has a high mortality rate.Reference Gutiérrez Fonseca1

Head and neck cancer patients have a high oropharyngeal dysphagia prevalenceReference Gutiérrez Fonseca1 related to different causes. They usually have a painful swallow. There is a direct impact of tumour size and location in bolus progression throughout the upper digestive tract.

The presence of a tracheostomy impairs swallowing. It reduces sensory input and subglottic air pressure and induces laryngeal structure disuse atrophy, all of which may increase the risk of aspiration.Reference Skoretz, Anger, Wellman, Takai and Empey2 There are side effects with regard to cancer treatment. Surgery produces fibrosis and structural changes in the upper aerodigestive tract. Chemoradiation therapy is associated with a painful inflammation, oral and pharynx mucositisReference Pauloski, Rademaker, Logemann, Lundy, Bernstein and McBreen3 and xerostomia, peripheral neuropathy, and muscular fibrosis.Reference Terlingen, Pilz, Kuijer, Kremer and Baijens4,Reference Hutcheson, Lewin, Holsinger, Steinhaus, Lisec and Barringer5 In cases of severe oropharyngeal dysphagia, oral feeding is not possible, and it is necessary to place a feeding tube or a gastrostomy.

Oropharyngeal dysphagia induces a decreased quality of life (QoL) in these patients, interfering with their social relationships and the pleasure of eatingReference Hutcheson, Lewin, Holsinger, Steinhaus, Lisec and Barringer5 and is even worse if they have a tracheostomy.

Oropharyngeal dysphagia evaluation allows establishment of a safe feeding pattern that reduces the risks of aspiration and malnutrition, which are associated with a worse QoL and reduced immune response and tolerance to antineoplastic treatment and survival, in addition to increased post-operative complications, hospital stay and costs.Reference Viana ECR de, Oliveira I da, Rechinelli, Marques, de Souza and Spexoto6

Aspiration pneumonia is a severe complication of oropharyngeal dysphagia, which requires antibiotics and a long-term hospital stay, and it may be lethal. Aspiration pneumonia is probably the most important factor contributing to non-cancer and unknown deaths in head and neck cancer patients.Reference Patil, Noronha, Shrirangwar, Menon, Abraham and Chandrasekharan7 Therefore, we suggest that a diagnosis and evaluation protocol of oropharyngeal dysphagia in head and neck cancer patients is highly recommended.

Materials and methods

Patients diagnosed with head and neck cancer are evaluated at our oropharyngeal dysphagia unit, before and after cancer treatment. They all must give written informed consent in order to participate in this protocol. A dissociated database is employed, so there is no personal data that would identify patients. The Research Committee of Infanta Sofia University Hospital and the Ethics and Research Committee of La Paz University Hospital approved this study.

Patients must answer a screening questionnaire about oropharyngeal dysphagia. We use the Eating Assessment Tool-10, which is validated in Spanish.Reference Burgos, Sarto, Segurola, Romagosa, Puiggrós and Vázquez8 It is a self-administered, reliable questionnaire published by Belafsky et al. in 2008.Reference Belafsky, Mouadeb, Rees, Pryor, Postma and Allen9 It has 10 items that have to be scored from 0 (there is no problem) to 4 (there is a serious problem). The scores are added together, and a global score of 3 or more indicates that oropharyngeal dysphagia may be present (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Eating Assessment Tool-10 (Spanish version).

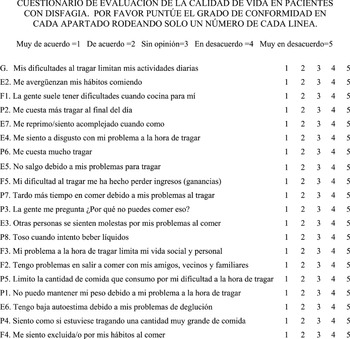

In addition, patients must fill in a swallowing-related QoL questionnaire. We used the MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory, which is validated in the Spanish head and neck cancer population.Reference Montes-Jovellar, Carrillo, Muriel, Barbera, Sanchez and Cobeta10 Chen et al. published this self-administered, psychometrically validated and reliable questionnaire in 2001.Reference Chen, Frankowski, Bishop-Leone, Hebert, Leyk and Lewin11 It has 20 items divided into 4 domains: the global domain (1 item) that summarises the overall QoL aspects related to swallowing; the emotional domain (6 items) that measures the emotional response to dysphagia; the functional domain (5 items) that evaluates the effect of dysphagia in daily activity; and the physical domain (8 items) that indicates the self-perception of swallowing difficulties.Reference Montes-Jovellar, Carrillo, Muriel, Barbera, Sanchez and Cobeta10 Each item scores from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree) while the global domain is shown separately. The composite score is obtained by adding the score of the last 3 domains, calculating their mean and multiplying this by 20. So, the composite score ranges from 20 (extremely low functioning) to 100 (high functioning).Reference Montes-Jovellar, Carrillo, Muriel, Barbera, Sanchez and Cobeta10 A score of 80 or more indicates minimal or no swallowing problemsReference O'Hara, Cosway, Muirhead, Leonard, Goff and Patterson12 (Figure 2). Hutcheson et al. demonstrated that the composite score shows less variability and a more consistent performance across clinical anchors of swallowing function.Reference Hutcheson, Barrow, Lisec, Barringer, Gries and Lewin13 Thus, the global domain that has only 1-item is used alone in order to obtain a quick view of the patient's swallow situation. Patients are then subjected to a complete otorhinolaryngological exploration in order to find any structural and/or functional impairment.

Fig. 2. MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory (Spanish version).

The last step is a flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallow. Patients swallow water dyed with food colouring and thickened with different amounts of food thickener according to the International Dysphagia Diet Standardization Initiative.Reference Badilla Ibarra14 Flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallow follows the Volume-Viscosity Swallow Test protocol.Reference Clavé, Arreola, Romea, Medina, Palomera and Serra-Prat15

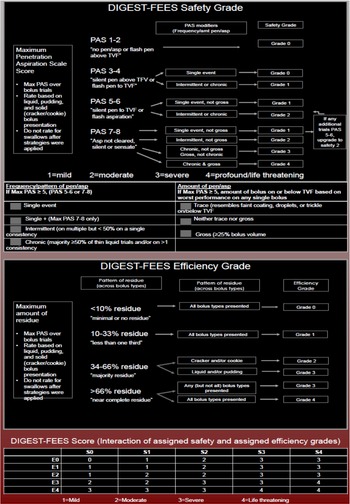

Flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallow data about efficiency and safety are classified according to the Dynamic Imaging Grade of Swallowing Toxicity for flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallow.Reference Starmer, Arrese, Langmore, Ma, Murray and Patterson16 This is developed based on the videofluoroscopic Dynamic Imaging Grade of Swallowing Toxicity™,Reference Hutcheson, Barrow, Barringer, Knott, Lin and Weber17 including the use of the Penetration Aspiration ScaleReference Rosenbek, Robbins, Roecker, Coyle and Wood18 to determine Dynamic Imaging Grade of Swallowing Toxicity-flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallow safety grades and the measurement of the percentage of pharyngeal residue to determine Dynamic Imaging Grade of Swallowing Toxicity-flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallow efficiency grades. The composite score is obtained by the interaction of the safety and efficiency grades. It ranges from 1 (mild) to 4 (life threatening) (Figure 3).

Fig. 3. Dynamic Imaging Grade of Swallowing Toxicity-flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallow (DIGEST-FEES). PAS = Penetration Aspiration Scale; Max = maximum; pen = penetration; asp = aspiration; TVF = true vocal folds

The composite oropharyngeal dysphagia features are classified according to the Dysphagia Outcome and Severity Scale.Reference O'Neil, Purdy, Falk and Gallo19,Reference Zarkada and Regan20 It is a 7-point rating scale, which measures oropharyngeal dysphagia severity based on videofluoroscopic swallow study. It makes recommendations for nutrition level, diet and independenceReference O'Neil, Purdy, Falk and Gallo19 (Table 1). Based on flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallow findings, patients receive recommendations about swallowing and diet adaptation in order to reduce the risk of aspiration and to maintain nutritional and hydration requirements. If necessary, a feeding tube is placed. Patients are sent to a speech and language pathologist if oropharyngeal dysphagia rehabilitation is required.

Table 1. Dysphagia Outcome and Severity Scale

Results

Seventy-two studies were evaluated according to the following protocol. Regarding the Eating Assessment Tool-10, 28 questionnaires (38.88 per cent) obtained a score below 3 points, so oropharyngeal dysphagia was ruled out. These 28 reports also reached a high MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory composite score (over 80 points). Flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallow results disclosed absence of oropharyngeal dysphagia in 25 cases, so they did not need a diet adaptation. A single patient received the recommendation to use thickeners to get an International Dysphagia Diet Standardization Initiative level 1, because Dynamic Imaging Grade of Swallowing Toxicity safety grade was 2. The other two patients were advised to modify their diet but without the need of thickeners.

Forty-four reports (61.11 per cent) presented with oropharyngeal dysphagia according to the Eating Assessment Tool-10, MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory and flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallow. A diet adaptation with thickeners was suggested for 5 cases to reach a level 1 and for 2 cases to get a level 3 of the International Dysphagia Diet Standardization Initiative. Recommendations such as eating a soft diet, avoiding sticky and dangerous food (like soup), using small spoons, taking small bites, and providing some kind of surveillance were advised for the rest of the cases.

In five examinations, oral feeding was not recommended, and a feeding tube was placed in four of them. The fifth was in need of parenteral nutrition because of a concurrent digestive pathology that contraindicated enteral nutrition. Only 2 studies out of 72 presented with aspiration pneumonia, but in one case the reason was because the patient refused to use a feeding tube in spite of our recommendation.

Discussion

An early diagnosis of oropharyngeal dysphagia is essential in head and neck cancer patients because of its high prevalence and its dangerous complications, such as aspiration pneumonia.

There are a lack of standardised protocols for the diagnosis and evaluation of oropharyngeal dysphagia in head and neck cancer patients. We presented a new protocol that reports the presence of oropharyngeal dysphagia, the QoL related to swallowing and the oropharyngeal dysphagia features regarding aspiration and residue.

There are some publications on the management of oropharyngeal dysphagia, and the systematic reviews agree that there is not a single way to diagnose oropharyngeal dysphagia.Reference Skoretz, Anger, Wellman, Takai and Empey2,Reference Terlingen, Pilz, Kuijer, Kremer and Baijens4 There are different oropharyngeal dysphagia-related questionnaires besides the Eating Assessment Tool-10 and MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory, such as the Functional Oral Intake Scale,Reference Crary, Mann and Groher21 Swallowing Disturbance Questionnaire,Reference Cohen and Manor22 the Swallowing-Quality of Life QuestionnaireReference Zaldibar-Barinaga, Miranda-Artieda, Zaldibar-Barinaga, Pinedo-Otaola, Erazo-Presser and Tejada-Ezquerro23 or European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Head and Neck-35.Reference Bjordal, Hammerlid, Ahlner-Elmqvist, de Graeff, Boysen and Evensen24

The oropharyngeal dysphagia diagnosis protocol that we present is very easy to carry out and very useful in the oropharyngeal dysphagia clinic. It only takes 20 minutes to be completed, and printed material and instrumentation are available in any otorhinolaryngology practice.

A limitation of this protocol is the impossibility of correlating our findings with videofluoroscopic swallow study because this technique is not available at our hospital. We have a radiological examination called ‘oesophagus deglutition function’ that indicates the presence of aspiration and residue, oesophagus mobility, and the presence of gastro-oesophageal reflux.

Conclusion

A protocol for oropharyngeal dysphagia diagnosis and management is necessary because it is such an important and dangerous impairment for head and neck cancer patients that we think it should be implemented at all hospitals. The protocol we present is easy, cheap, fast and available at any hospital, even at the bedside. This protocol uses questionnaires and examinations that are already validated and available worldwide. Its use can reduce the incidence of oropharyngeal dysphagia complications such as aspiration pneumonia.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Beatriz Bhathal Guede (MD), Cristina Andreu-Vazquez (PhD) and Israel Thuissard-Vasallo (PhD) from the European University of Madrid, Spain, for their advice.

Competing interests

None declared.