Introduction

The pedicled nasoseptal flap is useful in extensive skull base procedures for the reconstruction of bony defects. This novel technique has a favourable outcome in terms of reducing the risk of cerebrospinal fluid leaks, nasal crusting and septal necrosis.Reference Hadad, Bassagasteguy, Carrau, Mataza, Kassam and Snyderman 1 The advantages of the nasoseptal flap in the reconstruction of pharyngeal defects and velopharyngeal insufficiency have been documented in cadaveric experiments conducted by Rivera-Serrano et al.Reference Rivera-Serrano, Lentz, Pinheiro-Neto and Snyderman 2

Palatal reconstruction following subtotal or total maxillectomy is a surgical challenge. However, several authors have concluded that free flap placement is a good choice in head and neck defect reconstructions after tumour removal.Reference Clark, Vesely and Gilbert 3 – Reference Germain, Hartl, Marandas, Juliéron and Demers 7 It is appropriate to revisit the feasibility of local nearby flaps, such as the nasoseptal (Hadad's) flap, for limited palatal reconstruction following tumour removal (with disease-free margins) performed by a meticulous modified midfacial degloving technique assisted by endoscopic total maxillectomy. The present manuscript describes this technique and assesses the functional outcomes.

Case report

A 60-year-old Italian male, who was hypertensive, an ex-smoker and an ischaemic heart disease patient, presented with a 5-month history of pain and swelling over his left cheek. He had frequent episodes of blood-stained nasal discharge and left-sided nasal blockage.

He underwent a diagnostic nasal examination using a rigid endoscope. This revealed an irregular proliferative mass filling the nasal cavity and involving the left middle meatus, which was subsequently biopsied. Prior to the present surgery, the histopathology results were consistent with poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma.

A detailed investigation of the patient with radiological imaging (computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging) showed extensive lesions involving the left ethmoid and maxillary sinuses, with erosion of the medial wall of the maxilla and superior alveolar process of same side (i.e. left). There was no extension to the cheek, overlaying skin or posterior wall of the maxilla. The anterior skull base and orbit were normal.

On the basis of the radiological and endoscopic clinical findings, the tumour was diagnosed as stage IV, with a tumour–node–metastasis staging of T4aN0M0. The patient underwent surgical excision for radical removal of the tumour. This entailed a midfacial degloving technique, combined with an endoscopic-assisted transnasal and transoral radical total maxillectomy.

Under general anaesthesia by tracheostomy tube ventilation, an extended medial maxillectomy (type III) with concurrent excision of the nasolacrimal duct was performed. This was followed by submucosal dissection lateral to pyriform apparatus. The infraorbital foramen was identified. Subsequently, endoscopic sphenoethmoidectomy was performed. The bone at the junction between the maxillary tubercle and ethmoid crest was drilled to expose a posterior palatal area between the hard and soft palate, which was incised by diode laser. This was necessary given that it was a tumour and disease-free margins were required.

A modified midfacial degloving technique was performed via a traditional approach, with a transoral gingivobuccal and gingivolabial incision extending from the midline to the second molar teeth, as described in the literature.Reference Kim, Kim, Kang, Shin, Kim and Do 8 A vertical mucosal incision was made, keeping the cannon teeth of the other side, as shown in Figure 1. Osteotomy was performed by vertically cutting approximately 2 mm medial to the mucosal incision, connecting to the horizontal gingival incision. The maxillo-zygomatic junction was detached, and the block mass was removed by dissection and carried through the temporalis muscle. Haemostasis was achieved using endoscopic cauterisation. Multiple biopsies were taken from all margins after the specimen had been removed.

Fig. 1 Surgical steps for tumour removal in left hemi-maxillectomy: (a) transoral buccogingival incision; (b) modified midfacial degloving at the root of the septum; (c) oral incision through the hard palate; (d) transoral view of the palate defect after maxillectomy; (e) transnasal endoscopic view of the nasal cavity after left hemi-maxillectomy; and (f) maxillary body with the tumour, which was sent to histopathology after staining.

Frozen section analysis of the surgical margins proved negative; therefore, palatal defect reconstruction was arranged. A contralateral nasoseptal flap based on the septal branch of sphenopalatine artery was planned. The first incision was made above the tail of the superior turbinate, approximately at the level of the sphenoidal ostium of the contralateral side, which was carried anteriorly in the sagittal plane of the nasal septum, just above the axilla of the middle turbinate. Subsequently, the caudal incision was dropped down opposite to the inferior turbinate head, to preserve the anterior one-third of the septum. The second incision was made on the floor of the nose, from the junction of the soft to hard palate, and carried to join the septum incision caudally. Next, a medial choanal incision was made after the complete elevation of the flap, to release the flap medially, and a dissection was carried out in the ethmoidal crest, to narrow the pedicle of the flap in the contralateral side. Posterior septectomy was then performed like a window.

Palatal closure was accomplished with size 3.0 vicryl, with the periosteum facing the oral cavity and the nasal mucosa facing the nasal cavity. The closure was completed via an endoscopic oral and nasal route (Figures 2–4). A nasogastric tube was placed at the end of the surgery. The patient utilised the nasogastric feeding tube for 3 days; this was followed by a soft diet for the next 10 days.

Fig. 2 Reconstruction steps using the contralateral flap: (a) transnasal endoscopic view of nasoseptal flap elevation; (b) transoral view of rotated flap sutured to the defect's edge; (c) transnasal view of the nasal cavity after reconstruction; (d) transoral view of the total closed defect, with 4.5 cm scale measurement; (e) view of the reconstruction at two weeks post-operation; and (f) nasal view at two weeks post-operation. SS = sphenoid sinus; NSF = nasoseptal flap; MPC = mucoperichondrium

Fig. 3 Radiological images: (a) pre-operative, coronal, T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, showing stage IV maxillary sinus squamous cell carcinoma involving the medial wall and floor of maxilla; and (b) one-year post-operative, coronal, T1-weighted MRI, showing complete closure of the defect, with no locoregional recurrence. R = right

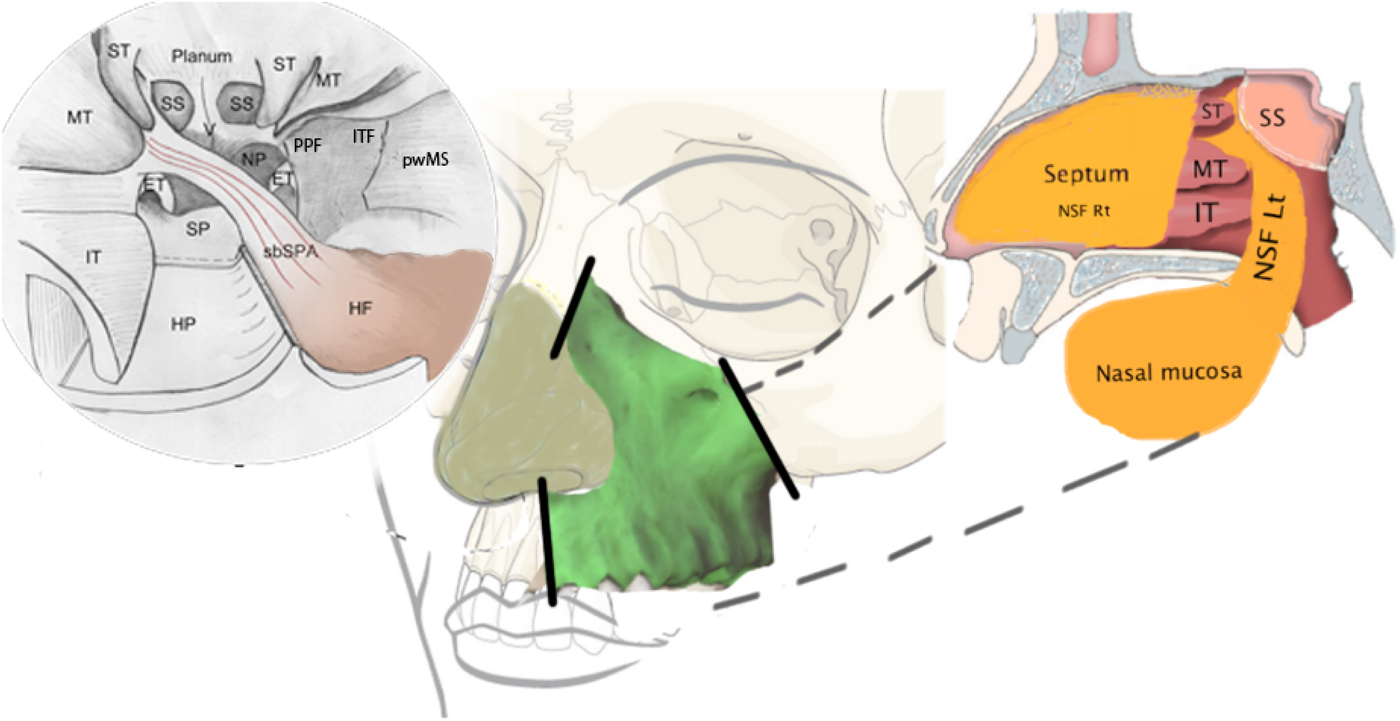

Fig. 4 Schematic drawing of the total maxillectomy and reconstruction. The upper right image is an endoscopic view of the planned reconstruction surgery. The centre image shows the area of the maxilla and the osteotomy lines (the solid lines). The upper left image is a sagittal view of the reconstruction procedure. IT = inferior turbinate; MT = middle turbinate; ST = superior turbinate; SP = sphenopalatine; HP = hard palate; sbSPA = septal brach of sphenopalatine artery; SS = sphenoid sinus; HF = harvested flap; NP = nasopharynx; PPF = pterygopalatine fossa; ITF = infratemporal fossa; pwMS = posterior wall of maxillary sinus; ET = Eustachian tube; NSF Rt = nasoseptal flap left side; NST Lt = nasoseptal flap right side

Follow up appointments after 1, 4, 6 and 12 months showed complete healing of the flap, with a small residual hole, which was repaired with a local rotated palatal mucosal flap, after a course of radiotherapy.

Discussion

Maxillary tumours are usually treated by traditional approaches, such as lateral rhinotomy, midfacial degloving and the Weber–Fergusson approach. They each have their own surgical implications, such as increased morbidity, unsightly facial scars associated with wide exposure, and visibility.Reference Lund 9 Minimally invasive endoscopic maxillectomy techniques are advantageous only in selected cases with limited tumour involvement. The use of endoscopes in treating sinonasal tumours has eased accessibility and aided precise tumour removal. These instruments provide a magnified view, precise dissection, control of osteotomies and superior control of intra-operative bleeding. When used in combination with current open approaches, endoscopes can improve surgical outcomes.

However, the reconstruction of surgically created bony defects poses difficulties to surgeons. Maxillary reconstruction remains a challenge in terms of optimal aesthetic and functional outcomes.Reference Clark, Vesely and Gilbert 3 The type of reconstruction to use is unclear.Reference Germain, Hartl, Marandas, Juliéron and Demers 7 Reconstruction mainly depends on the placement of palatal obturators and/or free flaps with microvascular anastomosis, which are harvested from a distant donor site, which in turn increases the morbidity and need for additional surgical intervention.Reference Moreno, Skoracki, Hanna and Hanasono 10 , Reference Bernhart, Huryn, Disa, Shah and Zlotolow 11

Palatal obturators are frequently used to treat small and medium size defects, and they represent the ‘gold standard’ technique in terms of functional restoration without the need for additional surgery. However, the prostheses can be problematic because of prolonged maintenance, and they are particularly inconvenient for people with poor manual dexterity or visual impairment. Other disadvantages include the nasal voice, regurgitation of liquid and sticking of food particles to the prosthesis.Reference Futran, Wadsworth, Villaret and Farwell 5 , Reference Moreno, Skoracki, Hanna and Hanasono 10

Over the past 30 years, the best reconstruction technique for the palate after total or radical maxillectomy, which gives excellent closure of the defect, particularly in advanced cases requiring subsequent chemoradiotherapy, has been free flap transfer with or without bone replacement.Reference Clark, Vesely and Gilbert 3 – Reference Germain, Hartl, Marandas, Juliéron and Demers 7 However, the multi-level surgical procedures required in the oral cavity, neck, and forearm or thigh, which usually require both the head and neck surgery and plastic surgery teams, add to the morbidity, cost and time. Other disadvantages include the prolonged duration of anaesthesia and risk of flap complications that may require a second surgical procedure.

The nasoseptal flap has been frequently used since it was popularised by Pittsburgh's research group for endoscopic reconstructions of medium to large defects of skull base tumour surgery.Reference Hadad, Bassagasteguy, Carrau, Mataza, Kassam and Snyderman 1 It revolutionised the reconstruction modality of skull base defects present after the surgical extirpation of tumours.Reference Hadad, Bassagasteguy, Carrau, Mataza, Kassam and Snyderman 1 The technique is associated with a fast healing process, fewer complications at the donor site and easier local accessibility, which are factors that help to improve the outcome and the patients’ quality of life.

The versatility and availability of the nasoseptal flap from the immediate vicinity, and the avoidance of another surgical procedure for a distant flap, suggest that the flap can be used more often in posterior fossa reconstructions and in palatal reconstructions (as in the present case). This paper reports the first known case of palatal defect closure with a contralateral nasoseptal flap (Hadad's flap), using a modified midfacial degloving technique assisted by endoscopic endonasal and transoral total or subtotal maxillectomy, for maxillo-ethmoidal squamous cell carcinoma.

-

• Squamous cell carcinoma of the maxilla is a common head and neck malignancy

-

• Endoscopic transnasal extended medial maxillectomy followed by modified midfacial degloving is a well-described technique

-

• In this case, a contralateral nasoseptal pedicle flap was successfully used to reconstruct the defect

The nasoseptal flap in the current study, which was based on a posterior nasoseptal artery (a branch of the sphenopalatine artery),Reference Rivera-Serrano, Terre-Falcon and Duvvuri 12 was thick and long enough to cover the defect of 4.5 cm × 3 cm, with a meticulous elevation of mucoperichondrium flap of the contralateral side. Posterior septectomy created a passage hole for the flap, allowing us to reach the most anterior and lateral part of the alveolar process for closure of the defect, as shown in Figures 3 and 4. Apart from transient nasal crusting at the donor septum, which usually mucosalises after 6–12 weeks’ time,Reference Rivera-Serrano, Lentz, Pinheiro-Neto and Snyderman 2 and the rare occurrence of nasal speech, the flap was well tolerated and taken up in the reported case. However, long-term assessment of this closure technique is needed given the velopharyngeal insufficiency, obstructive sleep apnoea and swallowing problems encountered in large series.Reference Willging 13

Conclusion

Multiple techniques have been reported for palatal reconstruction following radical maxillectomy, with free flap transfer (with or without bone replacement) being the most popular technique. Although this is the first report of the technique, the use of a pedicled nasoseptal flap for palatal defect reconstruction after subtotal or total maxillectomy appears to have a beneficial outcome. However, more case studies are needed to examine cosmetic and functional factors.

Acknowledgement

The authors of this manuscript would like to thank Dr D Lepera (Ospedale Di Circolo E Fondazione Macchi, Varese, Italy) for helping us with the schematic drawing presented in the manuscript.