1. Introduction

While it is a truism that no country can increase its living standards without economic growth, it is equally evident that all countries, throughout history, have the capacity for growth. Both historically and at present, however, the hurdle has been that years of growth are frequently offset by years of shrinking, which have resulted in stagnant living standards. By implication, economic history suggests that the ability to reduce years of shrinking is key to modern economic growth. The remaining problem for the analysis of long-term economic progress, however, is that we still know very little about why some countries increased their resilience to economic shrinking. To our knowledge, this case study is the first to approach this subject.

Indonesia represents the dramatic change in fortune that has been displayed in Asia. Between 1950 and 1966, Indonesia was marred by political and economic turmoil and the amount of shrinking years over this period almost equalled its years of growth. Economic shrinking is defined as a year when per capita growth is less than zero, i.e. when GDP per capita from one year to another ‘shrinks’. The country was in most respects an average underdeveloped country: GDP per capita was at a level below many African countries and one of the lowest in Asia (Booth, Reference Booth2016). The Malthusian trap was about to slam shut (Bresnan, Reference Bresnan1993) and the level of industrialisation accounted for just over 10% of GDP (World Bank, 2020).

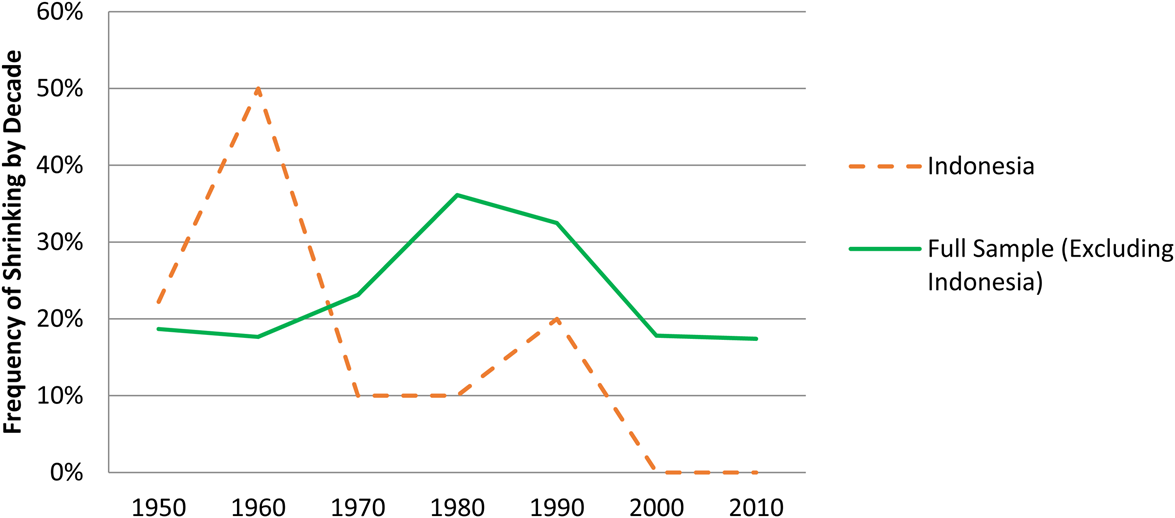

Furthermore, the level of social and political tension led to a failed coup in 1965 and the army gaining full control through an authoritarian regime under the rule of President Suharto. Despite the repressive nature of the state, and periods of crony capitalism largely based on resource extraction, Indonesia from 1967 until 2015 experienced only four years of shrinking, and income per capita grew by a factor of six to US$11,912 in 2015 (TED, 2019). Indonesia is now one of the world's largest democracies and, since 2008, a member of the G-20. As shown in Figure 1, at the beginning of the period under study, in the 1950s and 1960s, Indonesia shrunk at a higher frequency than the average of the poorest quarter of countries in the world. From the 1970s onwards, however, the frequency of economic shrinking in Indonesia has been greatly reduced. Such shifts in patterns are not without antecedents. Taking the case of Sweden as a historical analogy, its annual national accounts since 1560 indicate the shift from a shrinking-prone to a shrinking-resilient economy: from 1560 to 1870, almost every second year (49%) was on average a year of shrinking, whereas from 1870 to 2010, it dropped to one in five (19%). Similar to Sweden, all advanced industrial economies in the world have, during the last two centuries, experienced a shift from a shrinking-inclined economy to a shrinking-resistant one (Broadberry and Wallis, Reference Broadberry and Wallis2017).

Figure 1. Frequency of shrinking per decade 1950–2010 – Indonesia and low-income countries.

Source: elaborated by the authors based on data from the Total Economy Database (TED). The full sample includes 32 countries that were at the bottom 25% of the global income distribution between 1960 and 1965.

Unfortunately, growth theory is of limited use to help us understand this transition. Theories of economic growth, typically focussing either on accumulation and productivity, or on innovation and technological change, provide plausible explanations of sources and mechanisms of economic growth per se. These theories, however, offer little guidance as to why economies shrink. One strand in the macroeconomic literature has put the finger on the phenomenon on growth reversals, noting the phenomenon that growth occasionally turns negative (Easterly et al., Reference Easterly, Kremer, Pritchett and Summers1993; Pritchett, Reference Pritchett2000; Rodrik, Reference Rodrik1999). But even so, this provides no clues as to what causes an economy to increase its resilience to shrinking.

We aim to increase the understanding of how and why Indonesia managed to shift from a shrinking-prone economy to an economy where the frequency of shrinking has been largely reduced. Though our time frame extends to 2015, we argue that the main explanations for the success of the past two decades can be found in the Suharto era. Consequently, the focus of the paper is on the period up to 1997; the post-Suharto era is only touched upon to highlight that the resilience to shrinking continued well into the new millennium. In the paper, we present and apply a framework proposing what national traits should be in place to enable economies to systematically reduce their susceptibility to economic shrinking.

This study takes as a point of departure observations from Violence and Social Orders (Reference North, Wallis and Weingast2009) by North et al., particularly the distinguishing features of the transition from a limited access to an open access society. The authors argue that this transition, which is a recent phenomenon in the history of human societies, has so far only involved a small minority of the countries in the world. The reason why so few have managed to become open access societies is, according to the authors, that such a transformation requires sustained and progressive long-term economic performance that has two major characteristics: (i) the road to an open access society is marked by an arduous process of institutional changes and, which is less acknowledged, (ii) a society's successful transformation depends on its record of shrinking rather than its growth-generating abilities. In the proposed framework, the process towards reduced shrinking is associated with the gradual establishment of certain institutional and societal attributes, the so-called ‘doorstep conditions’ to become an open access society. The problem for more empirical analyses is that these attributes or conditions change only slowly and are largely intangible.

To pin down analytically sound and operationalisable measures to employ for contemporary and more short-term analyses, we adopt a social capability approach as a way to capture the possible changes in doorstep conditions that we argue strengthen the resilience to shrinking. In general, the social capability thesis holds that the potential for rapid growth could be realised if the economy is ‘technologically backward but socially advanced’ (Abramovitz, Reference Abramovitz1986). Although the social capability literature remains divided, its most frequently adopted metrics include educational levels and skills, experience with large-scale enterprises, quality of institutions, state capacity or social cohesion and adaptation to foreign technologies (Rodrik, Reference Rodrik2011).

Andersson (Reference Andersson2018) has recently developed a modified approach to social capability. He defines five theory-grounded and empirically transparent and interactive processes, rather than outcomes. Following that approach, we see social capability as a set of national characteristics that constitute more deep-seated determinants of the long-term growth trajectory rather than determinants of the short-term ability to create growth. By implication, social capabilities are theoretically factors related to the resilience to shrinking. Hence, our adoption of the social capability approach is not an attempt to cover all decisive elements of the growth process, but to capture plausible reasons behind why an economy becomes better at avoiding economic shrinking.

The contribution of this paper is to provide an empirically supported narrative, guided by our capability framework, that reflects the institutional and structural changes that account for the increased resilience to shrinking in modern-day Indonesia. Our analysis echoes the analytic narrative approach of Rodrik (Reference Rodrik2003) in the sense that we, through a country narrative, attempt to understand puzzling aspects of economic performance (the shift from an oft- to a seldom-shrinking economy) that are not explained by the proximate determinants of economic growth in ordinary growth theory. Alston (Reference Alston, Brousseau and Glachant2008) also stresses the merits of a case study approach when studying institutional change.

For the empirical sections of the paper, we have compiled data for the measurement of different indicators of our capabilities directly from the statistical yearbooks (published by Statistics Indonesia, Badan Pusat Statistik (BPS)), as well as the rarely used annual reports from the Indonesian Central Bank. This allows for more comprehensive data from the period before 1970. For GDP estimates, we rely on the Total Economy Database (TED) from the Conference Board. In terms of the record of the frequency of economic shrinking, the TED corresponds closely to other authoritative data on Indonesia, such as van der Eng (Reference Van der Eng2010). For the consistency of international comparison, the TED is used.

The paper is divided as follows. In the next section, we present our analytical framework, based on the merging of the historical framework of North et al. (Reference North, Wallis and Weingast2009) and our reconstructed version of Abramovitz's (Reference Abramovitz1986, Reference Abramovitz, Koo and Perkins1995) social capability approach. The third section provides a brief overview of the growth and shrinking record of Indonesia between 1950 and 2015. The fourth section discusses the institutional changes, understood as changes in the social capabilities of state autonomy and accountability, that have increased Indonesia's resilience to economic shrinking. The fifth section briefly reviews developments outside the direct control of the state, specifically the rise of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The sixth section concludes.

2. Analytical framework: state transitions, social capability and economic shrinking

In Violence and Social Orders, North et al. claim, albeit in passing, that economies transitioning to democratic and economically advanced open access societies do so because they manage to reduce the frequency of shrinking years rather than having higher growth rates (Reference North, Wallis and Weingast2009: 4). In this approach, as well as in subsequent writings by Broadberry and Wallis (Reference Broadberry and Wallis2016, Reference Broadberry and Wallis2017), the ultimate explanatory factor for containing economic shrinking, and consequently improving long-term economic performance, is institutional change. The most prominent among such changes is the emergence of rules in society that are impersonal rather than based on identity. Such rules will strengthen the adaptive efficiency of a society to handle shocks, crises and disruptive competition over rents.

The open access order signifies impersonal competition in both politics and the marketplace. Such competition places an automatic restraint on excessive rent-creation among excessively narrow-based interests through ‘creative destruction’, which will be activated in a Schumpeterian manner as more and more actors compete for the same rents. Political and economic power will then not be tied to a particular elite coalition but shift continuously. Open access societies are a recent and still atypical phenomenon in human history, first emerging some 200 years ago and as of yet comprising only 10–15% of the countries in the world. The remaining 85–90%, corresponding to approximately 85% of the global population, reside in different forms of limited access orders, in what North et al. refer to as different types of natural states. Such states have been the typical form of human society over the last thousands of years.

In their framework, North et al. stress that the transition from natural states to open access societies requires the fulfilment of three specific doorstep conditions that can be characterised as major institutional changes: (i) rule of law for elites, meaning that ‘the law applies equally to all elites and are enforced without bias’ (p. 156–7); (ii) perpetually active organisations in the public and private spheres, meaning that the life of each body is ‘defined by the identity of the organisation rather than the identity of its members’ (p. 152); (iii) consolidated control of the military so that there exists a legitimate monopoly of violence under the control of the governing coalition. Further, the military does not interfere in the political and economic spheres. In limited access-style governments, privileges are typically limited to the members of the dominant coalition; stability is secured by political bargaining among the elites, which creates incentives for cooperation and minimise the risk of elite groups targeting one another. The political system associated with the natural state typically ‘manipulates the economic system to produce rents that then secure political order’ (p. 18). Hence, it is given that in natural states, relations are often personal rather than impersonal, the economic and political spheres are closely intertwined and differing interests are manipulated by elites to ensure the stability of the current social order.

In contemporary Asia, some of the high-performing Tiger economies, such as Taiwan and South Korea, have arguably just fulfilled the doorstep conditions to become full-blown open access societies. However, the rest of the emerging economies in the region are for the foreseeable future still variants of natural states. The North et al. framework makes a crude distinction between three different progressive categories of limited access natural states: fragile, basic and mature.Footnote 1 These three types are useful for a broad categorisation of the quality and complexity of states both historically and contemporarily, although the authors acknowledge that they only provide a rough idea of these distinctions.

For our purposes, fragile states, exemplified by today's Somalia, Iraq and Haiti, are not our focal point. It suffices to say that such states are inherently unstable with rudimentary institutional structures and non-durable forms of public and private law. Of more relevant concern is the shift from a basic to a mature natural state. Here we find countries such as Brazil, Indonesia and other emerging economies in the developing world that during recent decades have grown into regional economic powerhouses.

As a society makes such a transition, more complex forms of organisations develop and more ‘credible institutions evolve that provides organisations with a measure of rule of law’ (p. 73). Moving from a basic to a mature natural state signifies the evolution of more complex elite organisations, for instance: (i) the ability to diversify revenues; (ii) less manipulation of the economy so that actors beyond the ruling elite are allowed to rise; and (iii) an increasing ability to make use of public resources for the progress of the society as a whole. At the same time, mature natural states fall short on many accounts compared to the institutional set-up of open access societies. They may, for instance, hold elections and adopt some democratic practises but lack ‘a wide range of institutions that support open access democracy’ (p. 137). Also, since natural states are governed by personal rather than impersonal rule, ‘natural states cannot sustain public goods and social insurance programs that share widely the benefits of the market economy in ways complementary to markets’ (p. 137).

The North et al. framework, in conjunction with the Broadberry and Wallis extensions, serves as our entry point for structuring the discussion of resilience to shrinking in low-income countries. The crucial institutional changes that drive long-term development in their framework, however, are too unspecific to be empirically captured. Further, their outline lacks guidance on how to analytically link social change to resilience to economic shrinking for more short-term and contemporary processes of economic development. The attention span of their approach is several hundred years, whereas we aim to disentangle changes over a much shorter period. For this, we need measurable indicators. The important question is how and why a limited order natural state begins to adopt the institutional changes (the doorstep conditions) that enable a society to transform into an open access society.

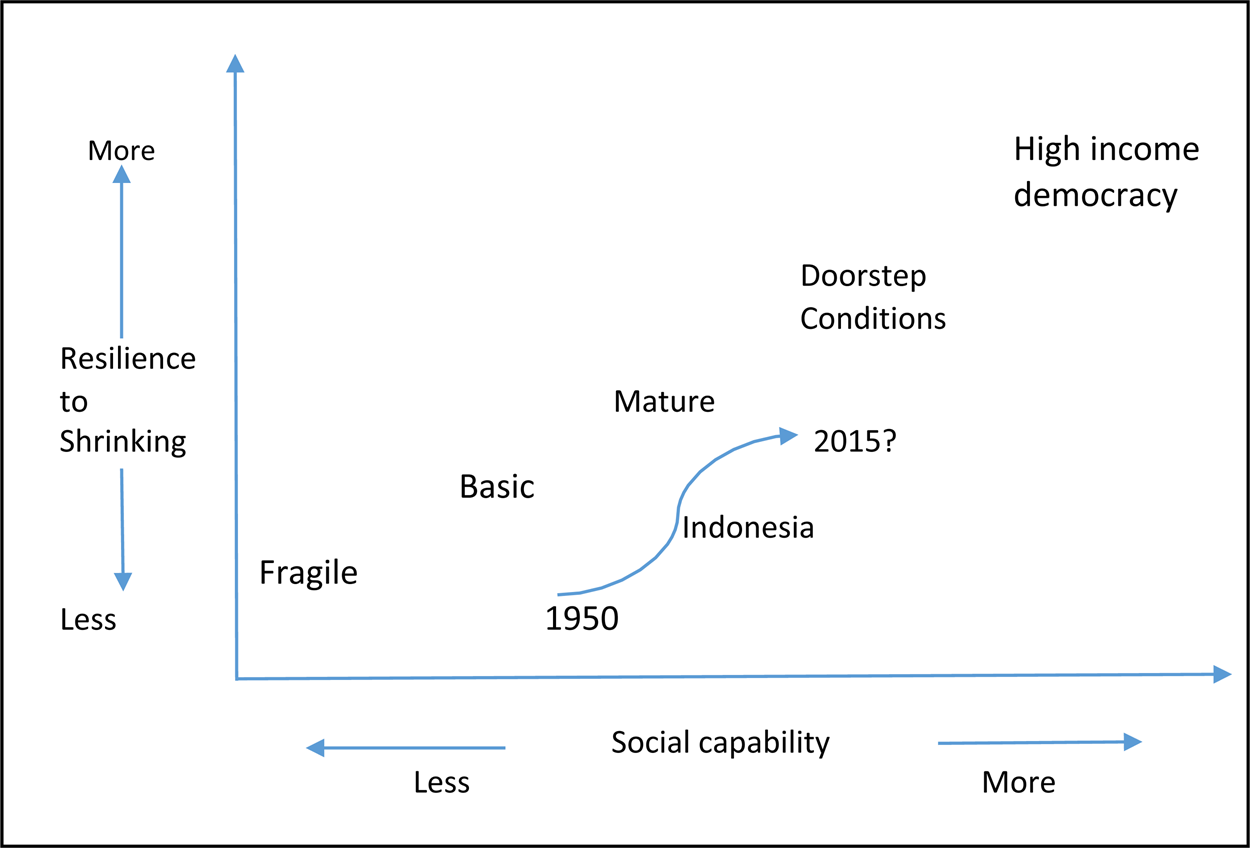

To empirically substantiate development towards the doorstep conditions, we apply a social capability approach inspired by the work of Abramovitz (Reference Abramovitz1986, Reference Abramovitz, Koo and Perkins1995). Our point of departure is that social capability is positively associated with resilience to shrinking: the more capabilities, the stronger the resilience (see Figure 2). The strength of the Abramovitz framework is that it also brings in structural aspects that, alongside institutional changes, are regarded as central to the analysis of how and why countries enter a development process indicated by the reduced frequency of economic shrinking.

Figure 2. Illustration of the analytical framework.

Source: elaborated by the authors.

Following Andersson (Reference Andersson2018), we deconstruct the concept of social capability into five empirically operational and interconnected parts. These are: (i) transformation, which captures the completion of the agricultural transformation; (ii) inclusion, encompassing the fall in poverty, widespread access to productive resources and the opening up of the economy, implying that the growth process has the potential to be pro-poor and participatory; (iii) social stability refers to the arrangements constructed to curb social and political conflict; (iv) autonomy, which we understand to be the ability of the state to keep vested economic interests at bay while at the same time being sufficiently aligned with powerful actors for mutual commitment to development policies and goals; and lastly (v) accountability, which is understood to capture the quality of governance and provision of public goods (cf. Besley and Persson, Reference Besley, Persson, Auerbach, Chetty, Feldstein and Saez2013).

The different social capabilities outlined above are interconnected and difficult to disentangle into clear-cut elements. In reality, they are also subject to cumulative causation and mutual interaction. Nevertheless, we focus on two distinguishable elements that most clearly relate to the capacity of the state to create conditions for broad-based invigoration and stable rules of the economy, captured by the state's autonomy and accountability. More specifically, autonomy refers to the arrangements that limit powerful actors' ability to interfere with the credibility of the macroeconomic system concerning prices stability, deficits, volatility, etc. Accountability represents the policies and principles applied to the use of public resources that serve to increase the productive potential and living standards of a broad cross-section of society.

3. The growth and shrinking record: 1950–2015

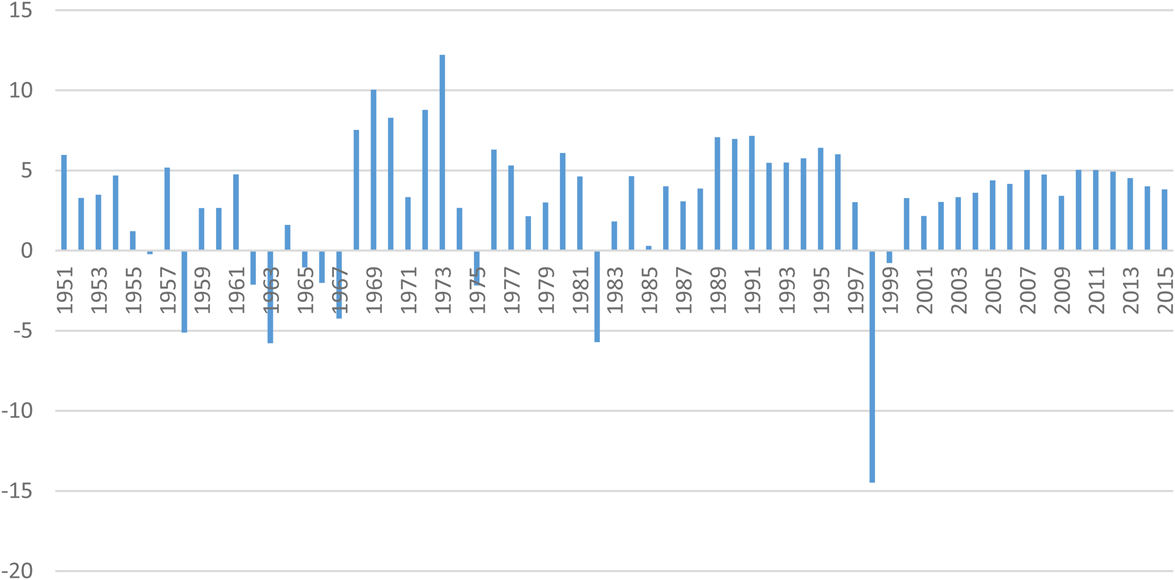

Indonesia's growth and shrinking record has some distinguishing features. The frequency of shrinking for Indonesia is equal to the average throughout Asia for the entire period, but seven out of its 11 shrinking years occurred in the 1950s and 1960s (see Figure 3). The new nation emerged under the leadership of President Sukarno, who came to power with a nationalist platform to develop the economy and society. The 1950s represent a politically tumultuous decade marked by increasing social tensions. Despite the general elections of 1955, which were followed by local elections, a clear-cut democratic system failed to emerge (see V-Dem, 2020). Instead, Sukarno established an authoritarian regime under the concepts ‘Guided Democracy’ and ‘Guided Economy’. At the time, Indonesia was one of the poorest countries in Asia and fit well into the North et al. categorisation of a basic natural state. Based on data from the Conference Board, the average income per capita in Indonesia after independence was 30% below that of the rest of Asia and 10% below that of African countries. The main source of growth was agriculture, which contributed 60% of GDP and employed over 80% of the labour force. However, food shortages and malnutrition were common. The spells of growth rates were regularly accompanied by three-digit rates of inflation between 1962 and 1968, pulling the rug out from under the poor and vulnerable.

Figure 3. Frequency and magnitude of growth and shrinking in Indonesia, 1951–2015.

Source: elaborated by the authors based on data from the Total Economy Database (TED).

In the final months of 1965 and early 1966, the Sukarno regime came to a violent end. A long-escalating conflict between the military and the Communist Party ended with the ousting of Sukarno, as Suharto seized both political and economic control. Politically, Suharto turned away from the socialist bloc and ended an ongoing conflict with Malaysia. In terms of economic strategy, the Suharto era also meant a redirection.

Between 1968 and 1975, income per capita growth was over 5%, with only one year of shrinking of −2% in 1975. It is interesting to note that the long-term transformation of the economy was not halted by the reliance on oil revenues during the first decade of the Suharto regime. Instead, the oil money was put to use modernising agriculture and industry simultaneously (as opposed to the typical pattern in other oil-rich developing countries such as Nigeria, see e.g. Henley et al., Reference Henley, Tirtosudarmo and Fuady2012). The increased oil prices and the ensuing improved terms of trade enabled the regime to increase investment broadly in the economy. This in turn led to greater productivity across sectors but particularly in agriculture (Sundrum, Reference Sundrum1986, Reference Sundrum1988).

Between 1976 and 1981, growth rates decelerated to an average of over 4%. Another year of shrinking occurred in 1982, at close to −6%, the main cause of which was the combined effect of a global economic downturn and plummeting oil prices, which affected Indonesia given the dominant role of oil in the economy.

By the mid-1980s, Indonesia demonstrated solid macroeconomic management and, with inflation under control and a major tax reform in place, self-sufficiency in food had been reached and its industrial sector contributed 40% of GDP. In 1993, a World Bank Report dubbed Indonesia one of the East Asian miracles (World Bank, 1993). Indonesia was heading towards New Industrial Country status. Suharto was firmly in power and the country was arguably one of the most centralised in the world (World Bank, 2003).

In mid-1997, the Asian crisis hit Indonesia. Although it had been heralded as the halfway miracle of Southeast Asia (World Bank, 1993), the Indonesian economy collapsed in 1998. Income per capita contracted by almost 15% in 1998–1999 (see e.g. Musyawwiri and Üngör, Reference Musyawwiri and Üngör2019). In the aftermath of the Asian crisis, some commentators attributed the sharp downturn of the Indonesian economy to built-in institutional weaknesses and the corresponding lack of resilience to economic shocks (e.g. Temple, Reference Temple and Rodrik2003). However, Indonesia did not fall apart as feared. Rather, it seems as if the institutional foundation laid by the Suharto regime quite paradoxically played an important role in the ensuing transition into democracy. Indeed, the Asian crisis led to the relatively peaceful ousting of the long-term ruler. Furthermore, the economy quickly returned to positive growth rates that have continued to the present. It seems evident that the economic stability from the second half of the Suharto paid off, in combination with the emergence of a relatively strong democracy with regional autonomy.

In 2008, Indonesia was rewarded with G-20 membership and, while the rest of the world suffered from the severe financial crisis in 2008, Indonesia steamed ahead. With democracy, Indonesia has improved greatly on scores measuring the rule of law and freedom of association (see V-Dem, 2020), which were acutely suppressed under the personalistic Suharto rule. Over the entire period under study, Indonesia shifted from a shrinking-prone to a shrinking-resilient economy. The remainder of the paper will focus on the changes taking place concerning the evolution of the social capabilities that we refer to as autonomy and accountability, with an emphasis on the steps taken before the introduction of democracy. Taken together, these indicators of social capabilities partly explain the increasing resilience to economic shrinking and enable an assessment of the progress made in the direction of approaching an open access society in terms of institutional changes, such as impersonal rules.

4. Changing social capabilities in Indonesia

4.1 Autonomy of the state

State autonomy is seen, in its broadest sense, as the ability to avoid being captured by vested interests through the rule of law and the capability to pursue credible long-term principles for the development of the country. This implies the ability to maintain a sound macroeconomic course without giving way to populist measures. To empirically capture the autonomy of the state, we focus on three interlinked aspects: the management of inflationary pressure; the ability of the regime to balance the budget and not engage in over-ambitious investments; and finally, the efficiency of taxation and sources of government revenues.

4.1.1 Inflation management

In the 1950s, the inflation rate of Indonesia was high but stable (Arndt, Reference Arndt1966). In the 1960s, this was to take a turn for the worse: in 1962 prices rose by 170%; in 1963 the process increased by another 134%, followed by rampant hyperinflation from 1965 on (Arndt, Reference Arndt1966; J.G., 1965; P.L.K. and H.W.A., 1966). The government response was to decrease the money in circulation by a currency reform with a conversion rate of 1,000 rupiah to one new rupiah. This did not stem inflation, as conversion to the new rupiah was a means for the regime to put into circulation rupiah notes that had been printed in the early 1960s but had been made obsolete by rampant inflation (P.L.K. and H.W.A., 1966). Furthermore, the regime engaged in inflation-driving policies by hiking wages for state employees and paying out bonuses (D.H.P., 1966). Additionally, the regime was faced with strong pressure from vested interests to maintain subsidies and preferential treatment both in terms of access to foreign currency and in the distorted value of the rupiah (P.L.K. and H.W.A., 1966). During the Sukarno era, there was thus a clear ineptitude to deal with the challenge at hand, reflecting the poor capacity of the state to promote a steady pathway for national development. It is also a clear indication of how the Indonesian state at the time lacked the capacity for autonomous governance.

After the ousting of Sukarno, Suharto surrounded himself with Indonesian economists trained in the US. This group of economists from the University of Indonesia, with training from the University of California-Berkeley and often referred to as the ‘Berkeley mafia’, was given the influence that would last well into the 1980s (Bresnan, Reference Bresnan1993). These economists had since the late 1950s advocated, to little success, a much more stringent economic policy to stabilise the economy and control inflation (Bresnan, Reference Bresnan1993). With Suharto in power, there was a change in economic policy as well as management. Suharto has been described as a tactician and not a strategist. After Sukarno, Suharto happened to be in the right place at the right time but lacked a long-term strategy as how to take power and rule the country (Vatikiotis, Reference Vatikiotis1993). This might explain why Suharto paid close attention to these economists.

The direction of economic policy in the first half of the 1960s had clearly not proved successful in delivering prosperity. To provide for the people, growth and development became paramount (McCawley, Reference McCawley, Ikhsan, Manning and Soesastro2002). The top priority was a stabilisation programme to shift the Indonesian economy in a positive direction and reschedule government debts, which, with the deficits of the Sukarno era, had skyrocketed to a level where Indonesia could not meet its obligations. This stabilisation strategy was drawn up with external support from the International Monetary Fund (H.W.A., 1966) and entailed a shift from the socialist and planned economy that had been the principal strategy of the ‘Guided Economy’ that was instituted in 1959.

By 1969, inflation was down to more manageable levels. This was mostly a result of the Suharto regime reorganising the budget. The 1970s saw three main spikes in inflation. The first was related to the rice crisis of 1972. With poor management of price-setting as well as the distribution of inputs from the rice procurement agency (Badan Urusan Logistik (BULOG)), in combination with dry weather and poor harvests in both Indonesia and abroad, the price of rice skyrocketed, directly impacting the cost of living (Grenville, Reference Grenville1973). The two other spikes in inflation were both related to the oil price hikes of 1973 and 1979. In both years, Indonesia was faced with a windfall that enabled the country to invest in development projects but also increased inflation (Hossain, Reference Hossain2012). It may be argued that the Suharto regime could have battled inflation more effectively and sterilised the unexpected oil windfall to a larger degree. Nevertheless, unlike the monetary and fiscal measures of printing currency and running deficits during the Sukarno regime, the government itself was not the driver of inflation.

Instead, the new strategy signalled a turn towards a more disciplined macro-economy and market orientation, where both private actors and the state played an important role. It was also a clear shift towards the capitalist Western world. In theory, this meant less involvement from the state with less preferential treatment for state-owned companies. While private businesses became increasingly significant, it is important to note that the role of the state was by no means to play a back-seat role in the development process. However, what is different from the earlier period is that Suharto put economic power in the hands of a group of relatively autonomous technocrats and thereby limited both his powers as well as the influence of other elite groups.

4.1.2 Balancing the budget

As noted above, in the final years of the Sukarno regime, the deficits were high and increasing. A first step for the Suharto regime and his technocrat advisers was to cut expenditures. In the first instance, these were lowered by ending the costly armed conflict with Malaysia. Costs were also reduced by scaling down the above-mentioned support for state-owned companies. Finally, some development projects, which did not result in quick returns, were to be scrapped or postponed (H.W.A., 1966). Indonesia addressed not only the current problems but also revised some of the underlying fundaments of fiscal policy that created a poor financial environment in the first place. The aim was to align government consumption with tax revenue. To this end, Indonesia created the so-called balanced budget principle.

The implementation of the balanced budget principle stemmed from the budget deficit that ballooned out of control in the final years of the Sukarno regime (Aghevli, Reference Aghevli1976). The balanced budget principle has been questioned as to how effective it was in fulfilling its immediate objective in terms of both avoiding deficits and avoiding inflation (Hill, Reference Hill2000). But even so, government representatives, including Suharto himself, refer to the balanced budget principle when arguing in favour of austerity programmes (Glassburner, Reference Glassburner1986). For instance, in times of crisis and the escalating deficits of 1975 and later in 1982, both high-profile and regular development projects were scaled back to balance the budget (Hanna, Reference Hanna1994). While it may be argued that this austerity policy led to slower growth (Sundrum, Reference Sundrum1988), it was a means to avoid a repeat of the hyperinflation that marked the Sukarno era. The budget constraint mechanisms remained in place, with low deficits even at the height of the financial crisis in 1997 and 1998 (Blöndal et al., Reference Blöndal, Hawkesworth and Choi2009; McLeod, Reference McLeod1997).

The balanced budget principle, even if it was not regulated by law, worked as an institutional constraint, and as such it prevented Indonesia from returning to the excesses of the Sukarno era and promoted sound macroeconomic policies (McCawley, Reference McCawley, Ikhsan, Manning and Soesastro2002). At the turn of the millennium, in democratic Indonesia, the budget-balancing system became more formalised and transparent as it became regulated by law (Blöndal et al., Reference Blöndal, Hawkesworth and Choi2009). Hence, the budget process and the restrictions in the use of public revenues became less muddled by pressure from actors and more guided by impersonal rule.

4.1.3 Securing revenue and tax reforms

In the Sukarno era, it was clear that not only did expenditures rise but revenues declined. The young nation inherited an antiquated taxation system from the Dutch that was heavily reliant on taxes on international trade (Asher and Booth, Reference Asher, Booth and Booth1995). Apart from taxes on trade, the government assessed numerous other sources including property and sales taxes. The tax system lacked institutional maturity and, with a large informal sector, tax-collecting abilities were limited. Consequently, tax evasion was rife, and levels of taxation often became a negotiation between collectors and payers (Odano, Reference Odano1987). With low efficiency and a limited revenue base, it was of the utmost importance to the regime to improve the taxation system. Looking at the Suharto administration as a whole, it is clear that tax revenues increased greatly over time (BPS, various years). This trend, if we exclude the dramatic effects of the financial crisis of 1998–1999, persists over time.

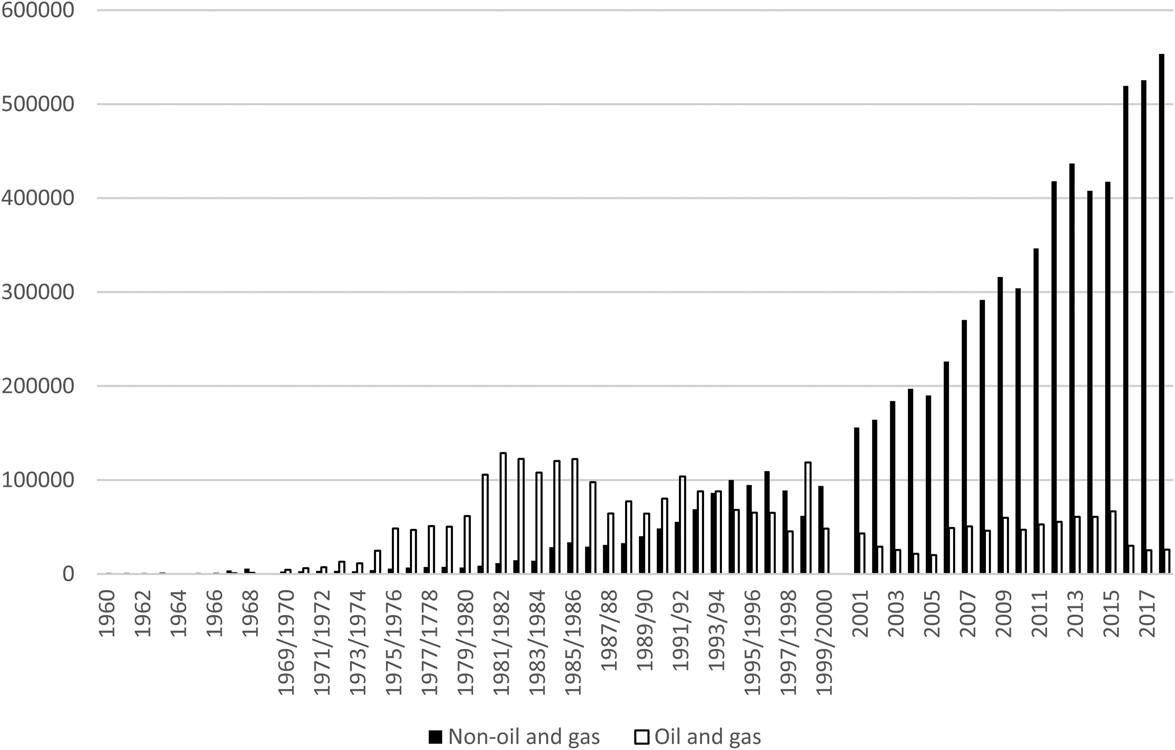

A closer look, however, reveals some issues that warrant further clarification. In Figure 4, we see how oil taxes start to increase after the oil shock in 1973 and peak in 1981. We can also see that non-oil taxes were negligible in the Sukarno era and during the first half of the Suharto regime but that there is a shift starting with declining oil prices. As regards tax revenue and GDP, it is clear that revenues soared as an effect of rising oil prices (Hill, Reference Hill2000). In fact, the increase in tax revenue in the 1970s is solely a result of escalating oil prices. With the declining oil revenues in the early 1980s, there was a slump in tax collection. It is not until the second half of the 1980s that we see a clear shift in the improvement in tax revenues. It may thus be argued that, with increasing oil revenues, which came with the oil boom of the 1970s, the pressure to reform the taxation system was minimal until a steep decline in the price of oil.

Figure 4. Sources of tax revenues, Indonesia 1960–2017.

Source: elaborated by the authors based on data from BPS and Bank Indonesia.

With the cash flow from oil decreasing in the early 1980s, Indonesia faced a revenue shortfall. The oil revenues had facilitated a lax tax regime, where the taxable elite were allowed to evade taxes. Recognising this hole in its revenues, Indonesia opted for tax reform. Economic constraints required a change from an inefficient and convoluted tax system to a simpler yet more effective one (see e.g. Asher and Booth, Reference Asher, Booth and Booth1995; Kelly, Reference Kelly1993; Odano, Reference Odano1987). This implied a move to a more diversified and impersonal system. Work on reforming the system began in 1981 and resulted in a tax law in 1984 (Gillis, Reference Gillis1985). In 1985, a value-added tax (VAT) was introduced to replace the domestic sales tax. The core change in income tax collection meant a simplification of the tax brackets from 19 to only three. The new system was built on self-assessment with penalties for evasion. Further, the VAT tax law was a simplification of the old system, moving from multiple rates to one (except for some luxury goods). Finally, the new land and building tax was also simplified with the institution of a single property tax (Asher and Booth, Reference Asher, Booth and Booth1995).

The more simplified system was a means to improve the efficiency of the taxation regime, but it also had other consequences. The Indonesian government took measures to educate the tax collectors and engaged in a reorganisation of tax collection, including instituting possible consequences for tax avoidance. While the tax reform in itself may be seen as standard, the most interesting part is how it was carried out. Rather than being a result of an indigenous process, it was the result of a top-down approach with very little Indonesian involvement. While the Ministry of Finance was nominally in charge, the work was carried out by a team from the Harvard Institute for International Development (Heij, Reference Heij2001). This international team was comprised of economists, lawyers, tax administrators and others (Gillis, Reference Gillis1985). Indonesian tax officials were informed rather than consulted. Furthermore, the process of pushing it through the legislative chambers was very opaque to avoid the influence of vested interests. Perhaps, more importantly, it was all done with the explicit support of Suharto (Gillis, Reference Gillis1985; Heij, Reference Heij2001).

The financial crisis of 1998 that continued into the new millennium had a strong adverse effect on tax revenues. This was due to the economy shrinking but also an effect of the more difficult conditions for tax collection given the initial social tensions (Iswahyudi, Reference Iswahyudi2017). As noted above, the end of the Suharto era was a watershed in Indonesia, which heralded a change in the form of both democratisation and decentralisation. The reforms in post-Suharto Indonesia were not only driven by the new political climate but also the need for revenue to circumvent the financial difficulties created by the crisis in 1998 (see e.g. Brondolo et al., Reference Brondolo, Bosch, Le Borgne and Silvani2008). The tax reform coincided with the upswing in revenues. While this is undoubtedly a consequence of the economic recovery, the momentum was maintained after pre-crisis levels were achieved.

It is worthy of note that, while the tax reform of the mid-1980s had a direct impact, the effect soon wore off and stagnation once again set in. This was very much a result of problems that pre-dated the previous tax reforms: the tax base remained narrow and taxation on non-oil revenues was still low. Although the tax system had been simplified, it was still complex, which led to lower levels of compliance and inefficient auditing (Brondolo et al., Reference Brondolo, Bosch, Le Borgne and Silvani2008). This was combined with the fact that the institutional context was weak. The tax authorities lacked capability – they were poorly organised and understaffed, both in terms of numbers and skills, and had little recourse to enforce compliance (Brondolo et al., Reference Brondolo, Bosch, Le Borgne and Silvani2008). Furthermore, Heij (Reference Heij2001) argues that while the process had been set up autonomously, many stakeholders, often through Suharto, soon gained influence and preferential treatment. Personal rule, although less strict, undoubtedly remained throughout Suharto's rule. However, the combined effect of the reforms executed cleared the ground for the relatively orderly transition to more open access procedures post-Suharto. For example, tax reform increased revenues based on a more diversified tax base. Indirect taxes (such as the VAT) became increasingly important and, if the temporary shock of the global crisis in 2008 is excluded, this momentum has been maintained (BPS, various years). This being said, Indonesian tax revenues remained low in comparison with its neighbours (Brondolo et al., Reference Brondolo, Bosch, Le Borgne and Silvani2008).

To conclude, Indonesia in the 1950s can be characterised as a politically and economically unstable nation lacking the capacity for autonomous decision making, despite its self-proclaimed Guided Economy label. During the Suharto era, state capacities evolved and the state was to a certain degree autonomous vis-à-vis vested interests, but the rule of law was severely curtailed. The role of civil society, including private entrepreneurs, politicians, journalists, trade unions and other social organisations not connected to the army or the Suharto family, was restricted. Numerous studies have shown that crony capitalism was entrenched in the regime (e.g. Temple, Reference Temple and Rodrik2003; Vatikiotis, Reference Vatikiotis1993), and senior army officials and other well-connected people were in charge of a range of sectors, such as forestry, automobiles, banking, airlines, hotels and tourism, among others (Robison, Reference Robison2009). However, over time through a series of key reforms, personal relationships and social position came to matter less in terms of economic decision making. Important institutional alterations were gradually taken during the Suharto regime that enabled Indonesia to adopt more open access features, including the strengthening of civil society, at a relatively rapid pace in the post-Suharto period.

4.2 Accountability

As a proxy for accountability, we use food security. A regime's dedication to and ability to deliver food security indicates how broad-based the development process is and provides information on whether government spending benefits a large stratum of society. In open access societies, the accountability of governments is strengthened by sophisticated systems of monitoring and institutional checks-and-balances in order to prevent leakages of tax revenues and other public resources. For basic natural states, like Indonesia in the early 1970s, feeding a poor, large and growing population is an enormous undertaking. In such states, measures taken to accomplish national food security are arguably the most compelling indicator of government spending to lift the productive potential of society at large. In the following, we refer to three layers of indicators reflecting food security. Firstly, the commitment from the state is assessed through the Indonesian budget allocation for agriculture. Secondly, we take a producer's perspective by examining institutional support for farmers. Finally, the institutional arrangements surrounding the pricing of the most important staple food, rice.

4.2.1 Investments in food production

Already from the onset of the Sukarno regime, Indonesia was faced with precarious food shortages. Food security was therefore a pressing issue. The regime promoted the use of chemical fertilisers and new seeds, but despite an increase in the agricultural budget, these efforts were chronically underfunded and entailed poorly organised efforts of guidance and support for new agricultural technologies (see e.g. J.G., 1965; Kolff, Reference Kolff1971; Roekasah and Penny, Reference Roekasah and Penny1967). In the early 1970s, prices for agricultural goods were below market prices and the domestic development policy was heavily biased against agriculture (Anderson and Martin, Reference Anderson and Martin2009). The result was that, while food production had increased, demand had grown faster.

As discussed above, at the time of the Suharto takeover, structural transformation had hardly begun and the economy was still dominated by the agricultural sector, with more than half of the labour force engaged in farming. Consequently, the development of the agricultural sector was, out of necessity, also important in the Suharto period. Despite this, the budget allocated to agriculture in 1971 equalled that of the final days of the prior regime (Bank Indonesia, BPS). With the rice shortages and ensuing price increases in 1972, it became clear that food security was equated to political security for Suharto. The principal approach of the Suharto regime was to increase subsidies on inputs and modern technology such as high-yield crop varieties, fertilisers, pesticides and irrigation coverage (Fane and Warr, Reference Fane, Warr, Anderson and Martin2009). As a result, some of the increased oil revenues in 1973 and later in 1979 meant that greater funds could be allocated to agriculture, rice in particular. This can be seen in the high levels of relative assistance to rice production (Fane and Warr, Reference Fane, Warr, Anderson and Martin2009). With the slumping oil prices in the early 1980s and the achievement of food security, Indonesia increasingly turned towards measures for industrialisation.

The end of the Suharto regime meant a change to a decentralised system where each region became responsible for its funding (Firman, Reference Firman2009; Simatupang and Timmer, Reference Simatupang and Timmer2008). Consequently, private interests and NGOs gained ground in the promotion of new cultivation practises, the mechanisation of agriculture and, more importantly, a shifting focus towards agri-business (World Bank, 2007). In this process, the relative distortions in Indonesian agriculture have declined but remain high for rice (Anderson and Martin, Reference Anderson and Martin2009; Fane and Warr, Reference Fane, Warr, Anderson and Martin2009). Even if the intention behind increased investment in agriculture might have been to secure political legitimacy on part of the ruling elite, the strategy was a thorough and advanced social project and created a solid foundation for broad-based development that extends to the present day.

4.2.2 Building an institutional framework for inclusive agricultural technology

Food security had been on the agenda during the Sukarno era and the government began experimenting with on-the-ground strategies for increased production as early as the 1960s. The programmes had shown good results but had been mostly small-scale experiments with little funding (Roekasah and Penny, Reference Roekasah and Penny1967). These programmes, called BIMAS, were not independent of the extension system but rather an effort directly targeted to increase food production, particularly rice, through mass guidance. In the early 1970s, The BIMAS programmes were expanded by the addition of the village units that consisted of a field extension worker, a village bank, which would provide the farmers with financial credit, and a village unit cooperative that, among other types of assistance, dealt with the distribution of inputs and marketing of rice. Essentially, food security was to be ensured through increased production and the integration of rice producers into the market. In the second half of the 1970s, achieving food security seemed within reach. Food availability increased steadily as production figures broke new records, but to stabilise yields, the central government went one step further through its third development plan (1979–1983) with the Insus programmes.

While the BIMAS programmes targeted individual farmers, Insus worked with groups. Each group had an appointed leader (Booth, Reference Booth1988). This enabled a more efficient structure to spread the use of new seeds and technologies. Extension officers would visit and instruct the so-called ‘contact farmers’ who, in turn, would disseminate the information to the larger group. The new system also permitted the stricter control of farmers ensuring that more followed instructions given by the officers (Booth, Reference Booth1988). Like its predecessor, the Insus programme targeted several food crops but the emphasis on the main staple crop, rice, remained. The Insus programme was specifically concerned with integrating more farmers into the production system and focused on regions where BIMAS had been less successful or had not yet fully penetrated. Insus meant that the system of extension officers coming out to the farmers and training them in how to use new technologies became the norm throughout Indonesia (Booth, Reference Booth1988).

By 1985, the country had achieved self-sufficiency in rice but there was still a concern for food security. The effects of the intensification programmes were wearing off and Indonesia was struggling to maintain high levels of production as well as keep up with the demands of a growing population and its increasing demand for rice (Sawit and Manwan, Reference Sawit and Manwan1991). Emphasis was put on modern varieties, new credit schemes, improved cropping patterns and practises, etc. This was carried out in part by building farmers' networks and increasing their levels of support through the addition of extension officers to visit the farmers and aiding them in any way they could, but also by involving village cooperatives as agents.

The intensification programmes and extension services were part of a broad-based strategy to increase production among all farmers. This was achieved through coercive methods but, more importantly, poorer farmers received subsidies and loans that allowed them to invest in new technology and improve their livelihoods without carrying the entire burden of the risk themselves. As a result, by the end of the Suharto regime, rural Indonesia had adopted a highly developed food production system. The end of Suharto's authoritarian regime, however, meant a change in the system where each region became responsible for its funding (Firman, Reference Firman2009; Simatupang and Timmer, Reference Simatupang and Timmer2008). The agricultural sector was opened to private interests and NGOs, often in collaboration with farmers' associations, that gained ground in promoting new cultivation practises, mechanisation of agriculture and, more importantly, a shift in focus towards agri-business (World Bank, 2007).

4.2.3 Rice price policy

Although subsidies were the principal means to address food security, price stability played a significant role as well. The regime engaged in increasingly sophisticated price manipulation to ensure that the growing population outside of agriculture could afford to put enough food, particularly rice, on the table. To this end, the regime created BULOG in 1967. BULOG was tasked with ensuring food security across Indonesia (Yonekura, Reference Yonekura2005). This was to be done by increasing storage capacities and evening out the food supply over time, helping to avoid seasonal surpluses and deficits, as well as building logistical capacities to transport food across the archipelago. This allowed BULOG to set prices both at the farm gate level and for consumers, which meant the protection of producers and consumers in tandem with price stability (McCulloch and Timmer, Reference McCulloch and Timmer2008). The monopoly was in place until the end of the Suharto regime, though some specialists have argued that it was most important until Indonesia achieved self-sufficiency in the mid-1980s (Yonekura, Reference Yonekura2005). It is clear that it was a costly organisation, which was rife with corruption and mismanagement (see e.g. Bresnan, Reference Bresnan1993; Yonekura, Reference Yonekura2005). At the same time, the price of rice remained remarkably stable throughout the Suharto regime, insulating the domestic market from regional downturns and fluctuations (Jones, Reference Jones1995; McCulloch and Timmer, Reference McCulloch and Timmer2008; Timmer, Reference Timmer1996).

Furthermore, it was in the interest of the politically influential rice milling industry to protect the sector from rice imports. Hence, smallholders in the rice sector also benefited from the rents created by the rice elites' measures to curtail international trade. Although food security was achieved in part by state-sponsored subsidies directed towards productivity-enhancing technologies and organisational improvements for rice farmers, the widely distributed rents created by the rice milling industry also improved the livelihoods of millions of smallholder rice farmers. It should also be kept in mind, however, that the comprehensive approach to stimulate the rice sector had no counterpart in policies to encourage the agricultural sector in general. Thus, the Indonesian approach was more directed towards self-sufficiency in rice than a full-scale agricultural transformation. Although the heavily centralised, and heavy handed, system of Suharto is long gone, food security has not disappeared from the current political discussion (see e.g. Adyatama, Reference Adyatama2020; Candra, Reference Candra2011).

5. Beyond the direct capacities of the state

It is worth emphasising that the process of long-term social transition has not been orchestrated solely by the actions of the state and even less so by purposeful government-made design. Indonesia's transition into a more shrinking-resilient society can be explained, we argue, by the institutional changes that we capture through the social capabilities of autonomy and accountability. But many parallel processes were generated by other mechanisms. For instance, the economic changes in Indonesia are associated with a more diversified and complex organisation of production where the dependence on natural resource exports and agriculturally based production has declined. When Indonesia gained independence in 1945–1949, the industrial base was minimal and natural resource-based. It has been argued, also by Sukarno, that Indonesia lacked a middle class (Robison, Reference Robison2009). Colonial policies had led to a shortage of private capital, a small domestic market and very few entrepreneurs who could act as agents of change. With these capital and labour constraints, the state became a main vehicle for industrialisation, directing capital towards key industries that were capital intensive but did not absorb much labour.

This trend was further accentuated by the nationalist, and later socialist, policies advocated by Sukarno. A further effort to overcome the perceived lack of a middle class was to rely on a small group of ethnic Chinese. Despite efforts to industrialise under Sukarno, few opportunities were created for the broader population. By the end of the Sukarno regime, the industrial sector contributed only 12% of GDP and less than 10% of the labour force (Timmer et al., Reference Timmer, de Vries, de Vries, Weiss and Tribe2015). The economy was dominated by large enterprises on the one hand and micro-businesses on the other (Seibel, Reference Seibel2019).

After the regime shift in 1965, Suharto was facing similar, if not worse, constraints as Sukarno. Suharto continued the industrialisation effort through state and army control over large enterprises, or by privately-controlled conglomerates with close connections to the presidency. A slump in oil prices at the beginning of the 1980s combined with the Plaza Accord, which changed the production costs and capital flows in Pacific Asia, meant a shift in the drivers of the industrialisation process to an export-oriented and labour-intensive manufacturing sector fuelled by foreign direct investment. This shift meant the agricultural labour force could be absorbed in the industrial sector, mainly into large enterprises but also into the growing segment of SMEs. The Suharto regime engaged in some programmes to encourage SMEs, but these were inefficient (Seibel, Reference Seibel2019) and the government continued to focus its support on cronies and large companies. As a consequence, the Indonesian economy became more diversified during the Suharto regime not because of – but rather despite – state policy. A broader production base also allowed for greater opportunities to participate in the economy.

Nevertheless, Suharto's leadership, be it by shrewd calculation or fluke, played a major role. For instance, introducing rice reforms and being receptive to outside advice enabled the strengthening of the Indonesian economy without jeopardising Suharto's own power, at least in the short run. The role of leadership is often a neglected aspect of long-term transitions but should not be overlooked (see e.g. Alston et al., Reference Alston, Melo, Mueller and Pereira2016, on the case of Brazil). Perhaps, as much of the literature on Suharto seems to suggest, one of his most successful leadership characteristics was that he did not seem to follow a pre-set master plan and that he understood he was not in possession of all the answers.

The financial crisis in 1997 meant the end of Suharto rule and, by extension, the circle of cronies around him suffered from the loss of their personal connection to power (Hallward-Driemeier et al., Reference Hallward-Driemeier, Kochanova and Rijkers2018). Today Indonesia is an industrial nation where a manifold and diverse group of elites has emerged. The large state-owned enterprises and the conglomerates, which had grown to become some of the largest companies in Asia under Suharto, still dominate the economy. The industrial landscape, compared to the Suharto era, has nevertheless transformed into one where economic activities are disconnected from a single political elite.

6. Concluding remarks

The shift to a development pattern less marked by shrinking is, according to our perspective, a major explanation for the vast strides Indonesia has taken in terms of its socio-economic and political development since independence. It suggests, in the terminology of North et al., that Indonesia, still far from an open access society, has shifted from being a basic natural state towards a mature natural state where the doorstep conditions for further advancement might be underway. The empirical indicators provided by our social capability approach shows that the country has engaged in both institutional and structural changes. It also demonstrates that this is a non-linear process where institutional changes, such as the move towards impersonal rule, occasionally were halted. Clearly, economic development, including the process through which social capabilities are acquired, is not confined only to measures taken by the state. We acknowledge that development is conditioned by the historical trajectories and accidents, social and economic forces as well as unintended consequences of political action, etc. In this study, we focus on state capabilities.

In terms of autonomy, macroeconomic management improved greatly under the Suharto regime. This was aided by a number of institutional changes. From 1967, the budget had to be balanced and was constrained by an institutional mechanism. The purpose was to limit extensive and unfunded development projects and thereby keep inflation at bay. Although the rules were soft, there are clear indications of impersonality that had implications at all levels of government and led to the postponement or even cancellation of projects in times of economic downturn. Even at the height of the financial crisis in 1998, the budget was balanced. The crisis and the ensuing decentralisation prompted reforms towards a more transparent and formalised budget process. Also, taxation became more autonomous throughout the Suharto period, but it was not a straight line to a fully sovereign and uncorrupted system. There was an attempt to shift towards transparent and impersonal rules with the tax reforms in the mid-1980s, but soon the autonomy was compromised by Suharto and those surrounding him. From 2001, reforms were underway to further formalise, simplify and professionalise tax collection.

The transformation in Indonesia has been remarkable and the country is today a manufacturing powerhouse with more than 40% of GDP derived from the industrial sector. However, the preconditions for industrialisation were very poor, with both labour and capital constraints. Indonesia, therefore, focused on a few specific sectors rather than a broad-based industrialisation with large-scale industries, both private and state-led, at the core of the process. The result was that, in the effort to industrialise, a small elite with close connections to Suharto could grow very powerful and enjoy benefits in the form of monopolies, state credits, etc. This became clear when Indonesia shifted towards more labour-intensive and export-oriented manufacturing in the mid-1980s. Despite the shift towards more labour-intensive industries, the power concentration remained until the emergence of democracy. This meant that there were restricted opportunities for entering certain markets and SMEs grew in spite of, not because of, government policies. The end of the Suharto regime meant a different business landscape. The conglomerates and many state-owned enterprises remained, but new groups emerged.

In terms of accountability, defined as food security, the development landscape shifts. The importance of food security and stability trumped other special interests. As a consequence, investments in agriculture were broad and an institutional structure was built to create equal access for farmers, rich or poor, to participate in the intensification programmes. Through the establishment of a well-oiled machine for dissemination of technologies, the focus was more on food production than farmers' income, yet it led to massive production increases on a broad scale. Despite progress and setbacks, the Indonesian strategy has been characterised by relative inclusiveness and the growth process has been strongly pro-poor, leading to continuously decreasing poverty rates.

Indonesia's capacity to increase its resilience to shrinking is a key, if not the most important, explanation as to why the country has developed favourably compared to its peers over the course of the past 50 years. The development of the social capabilities we have discussed is the major reason behind this progress. Whether Indonesia will continue to build resilience and acquire the full set of doorstep conditions to become an open access society is, however, still too soon to tell. Inflation is relatively high and tax returns as a share of GDP are low in a regional comparison. In addition, Indonesia continues to struggle with corruption. Although the country has climbed in the Transparency International corruption perception index, there is still a long way to go. The dominance of the Suharto family and his cronies may have been broken. The large conglomerates of the past have not disappeared, however, and today the connections between politics and the economy take different shapes and involve new and often locally powerful economic elites. For Indonesia to take a further step towards an open access society would require institutional changes that will distribute both rents and political voice more widely in society to limit its oligarchical structures. For the longer run, this will be crucial if Indonesia plans to remain a shrinking-resilient society.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg Foundation (MMW2014.0151) and Riksbankens Jubileumsfond (P18-0603:1) for funding. Research assistance from Viktor Lindelöw and comments on earlier versions of this paper from Montserrat Lopez Jerez, participants at the WINIR conferences in Hong Kong and Lund and three anonymous referees are gratefully acknowledged.