There is nothing more deceptive than an obvious fact.

Sherlock HolmesFootnote 1

The expression phoinikeia grammata is usually translated as ‘Phoenician letters’. This interpretation goes back to Herodotus, who linked phoinikeia grammata to the Phoenician origins of the Greek alphabet. Classical scholars and others have generally accepted his account, which has become the mainstay of the widespread notion that the Greeks took over the alphabet from the Phoenicians in the ninth or early eighth century BC. There are compelling reasons, however, to question Herodotus’ explanation. His account is internally inconsistent and presents chronological difficulties. It was also not the only, nor the oldest, theory about the introduction of the alphabet that circulated in antiquity. The enigmatic word φοῖνιξ can have a myriad of meanings in Greek; it does not just mean ‘Phoenician’; it may, for instance, also refer to a palm tree or the colour red.

The first part of this article will take a fresh look at the meaning of the expression phoinikeia grammata. It will examine the various existing traditions about the introduction of writing and phoinikeia grammata (sections I–II), and its attestations in classical texts (sections III–V). In section VI, it is concluded that phoinikeia grammata originally did not refer to the alphabet, but to Linear B writing on palm leaves and that the account of Herodotus is to be understood as the result of a ‘learned reinterpretation’. In the second part of the article, the main consequences of this new insight will be addressed. First, additional evidence will be presented to corroborate the hypothesis that the Linear B script was not written primarily on clay, but rather on perishable materials, notably palm leaves (section VII). In sections VIII–XI it will be argued that in classical antiquity there was, at least in some (learned) circles, historical awareness of the existence and use of pre-alphabetic writing systems in the Late Bronze Age Aegean, including a discussion of the terms σήματα and γράμματα and ‘Pelasgic letters’. Next, the possible motives for Herodotus’ false reinterpretation (XII) and its implications for the origins of Cadmus, the legendary bringer of phoinikeia grammata, will be discussed (XIII). Sections XIV–XV offer a synopsis of the main arguments presented in this article and their implications. Finally, the Appendix provides a succinct discussion of the epigraphic attestations that have been linked to phoinikeia grammata.

I. Herodotus and phoinikeia grammata

Herodotus (5.58.1–2) gives the following account of the introduction of the alphabet to Greece:

οἱ δὲ Φοίνικϵς οὗτοι οἱ σὺν Κάδμῳ ἀπικόμϵνοι, τῶν ἦσαν οἱ Γϵφυραῖοι, ἄλλα τϵ πολλὰ οἰκίσαντϵς ταύτην τὴν χώρην ἐσήγαγον διδασκάλια ἐς τοὺς Ἕλληνας καὶ δὴ καὶ γράμματα, οὐκ ἐόντα πρὶν Ἕλλησι ὡς ἐμοὶ δοκέϵιν, πρῶτα μὲν τοῖσι καὶ ἅπαντϵς χρέωνται Φοίνικϵς· μϵτὰ δὲ χρόνου προβαίνοντος ἅμα τῇ φωνῇ μϵτέβαλλον καὶ τὸν ῥυθμὸν τῶν γραμμάτων. πϵριοίκϵον δὲ σφέας τὰ πολλὰ τῶν χώρων τοῦτον τὸν χρόνον Ἑλλήνων Ἴωνϵς· οἳ παραλαβόντϵς διδαχῇ παρὰ τῶν Φοινίκων τὰ γράμματα, μϵταρρυθμίσαντϵς σφέων ὀλίγα ἐχρέωντο, χρϵώμϵνοι δὲ ἐφάτισαν, ὥσπϵρ καὶ τὸ δίκαιον ἔφϵρϵ, ἐσαγαγόντων Φοινίκων ἐς τὴν Ἑλλάδα, Φοινικήια κϵκλῆσθαι.

These Phoenicians, who came with Cadmus, including the Gephyraeans, settled in this land and transmitted to the Hellenes, among many other kinds of learning, the alphabet, which I believe the Greeks did not have before, but which was originally used by all Phoenicians. As time went on the sound and the form of the letters changed. At this time, the Greeks who lived around them were for the most part Ionians; they were the ones who were taught the letters by the Phoenicians, and after making a few changes to their form, put them to use and called these characters ‘Phoenician’—which was only just, since the Phoenicians had brought them into Hellas.

After a short exposé on the use of skins instead of papyri by the Ionians, Herodotus then goes on to say that he has seen ‘Cadmeian letters’, which in his view greatly resemble Ionian letters (5.59):

ϵἶδον δὲ καὶ αὐτὸς Καδμήια γράμματα ἐν τῷ ἱρῷ τοῦ Ἀπόλλωνος τοῦ Ἰσμηνίου ἐν Θήβῃσι τῇσι βοιωτῶν, ἐπὶ τρίποσι τρισὶ ἐγκϵκολαμμένα, τὰ πολλὰ ὅμοια ἐόντα τοῖσι Ἰωνικοῖσι.

I myself have seen Cadmeian characters in the temple of Ismenian Apollo at Boeotian Thebes, engraved on three tripods, and for the most part looking like Ionian letters.

Herodotus relates that one of these three tripods dates to the time of Laius, the great-grandson of Cadmus, one to the time of Oedipus, son of Laius and one to the time of Laodamus, son of Eteocles. Though the historicity of these mythical figures may now be doubted, they were regarded as historical persons by Herodotus. He estimated that Cadmus had lived before the Trojan War, some 1,000 years before his own time (2.145). Though there are good reasons to believe that the Greek alphabet was introduced much earlier than is currently assumed by most, such an early introduction is scarcely credible, and the reference to ‘Phoenicians’ in (pre-)Trojan War times is anachronistic.Footnote 2 It is also hard to imagine that such very ancient letters would have looked so similar to the script in Ionia of Herodotus’ time.

In addition to the chronological difficulties, the manner in which Herodotus frames the story calls for caution; he is known to use eyewitness reports to introduce material he knew was controversial.Footnote 3 As may be derived from the remark ‘I believe’ (ὡς ἐμοὶ δοκέϵιν), Herodotus was aware of the existence of contrasting views. A further reason for wariness is the fact that Herodotus’ discussions of inscriptions are often problematic. Archaeological discoveries in recent decades have revealed at least two examples of inscriptions that were plainly misunderstood by Herodotus, the Karabel inscription in western Anatolia (2.106) and the dedication of Croesus at Delphi (1.52).Footnote 4 The ‘Cadmeian’ dedications described by Herodotus in book 5 may likewise have been misinterpreted. Quite possibly, the inscriptions Herodotus claims to have seen were not ancient inscriptions from a distant past, but rather dedications from a much later period, dating to somewhere between the eighth and sixth centuries BC.Footnote 5

Though the above difficulties with the account of Herodotus and, more generally, the problems inherent to the use of Herodotus’ work for historical purposes, are well-known,Footnote 6 the gist of his exposition on phoinikeia grammata is generally accepted.Footnote 7 Considering the above, however, there are sufficient reasons to reassess the argumentation of Herodotus, and to explore alternative explanations.

II. Alternative traditions about the introduction of writing to Greece and phoinikeia grammata

The account of Herodotus is not the first, nor the only, ancient narrative about the introduction of writing to Greece and the meaning of the expression phoinikeia grammata. Footnote 8 The first known theory about the origins of writings is attributed to Stesichorus (seventh–sixth century BC), according to whom the Greek hero Palamedes was the inventor of writing. Lilian Jeffery has suggested that Stesichorus refers to an already existing tradition,Footnote 9 which is very probable, though not certain.Footnote 10 Next are the accounts of Hecataeus and Herodotus, which date to the fifth century. Hecataeus argues that Danaus brought the letters from Egypt, a view that is also found in some later authors.Footnote 11 The idea that it was Cadmus with the Phoenicians who introduced writing to Greece is first found in Herodotus, but it may have existed before him.Footnote 12 This theory was quite popular and taken up by various later authors. Most, however, also mention alternative theories and it appears that the ancients were divided about the origins of the Greek alphabet.Footnote 13 As mentioned above, the remark ‘I believe’ (ὡς ἐμοὶ δοκέϵιν) suggests that Herodotus himself was also aware of the existence of conflicting views, and Stephanie West has plausibly suggested that his account may have to be interpreted as a contribution to a current controversy.Footnote 14

In general, one can distinguish traditions that assert a foreign origin of writing (Phoenician, Egyptian, Assyrian) with Danaus, Cadmus, various individuals called Phoenix or the Phoenicians as inventors or mediators on the one handFootnote 15 and, on the other, traditions that ascribe the discovery to a Greek god or hero. Named as inventors are Prometheus, the Muses, Hermes, Sisyphus, Palamedes, Pythagoras and Simonides, and, from at least the fifth century onwards, Orpheus, Linus and Musaeus. In this context, reference is sometimes made to ‘Pelasgic letters’.Footnote 16 All inventions are situated in the Heroic Age, which is usually associated with the Late Bronze Age.

It may be clear from this very succinct overview that though the theory of Herodotus gained most acceptance, in antiquity it coexisted with other narratives. Of interest is the observation of Jean Schneider that it is surprising that the first surviving account at our disposal, namely that of Stesichorus, does not mention the Phoenician background of the Greek alphabet at all.Footnote 17 If one accepts the conventional model according to which the Phoenicians introduced the alphabet to Greece in the early eighth century, this would have been a relatively recent event and one might expect some reference to it. By contrast, all accounts, without exception, place the invention of writing much earlier, in the distant legendary past. With this in mind, let us now turn to the alternative explanations that have been adduced to account for the expression phoinikeia grammata.

In ancient Greek, the chameleonic word φοῖνιξ is open to multiple interpretations, ranging from mythical birds to diseases and musical instruments.Footnote 18 Liddell and Scott list no less than 12 different meanings with derivations.Footnote 19 The most well-known uses of φοῖνιξ that are relevant for the present investigation include:

-

‘Phoenician’, ‘Carthaginian’Footnote 20

-

‘purple’ or ‘crimson’

-

‘date palm’, ‘palm’

These three meanings are already attested in Homer, where the word occurs as a personal name (Φοῖνιξ) and is used to refer to palm trees and Phoenicians, as well as to the colour red.Footnote 21 The fact that the word φοῖνιξ has so many meanings has led to various different interpretations of the expression phoinikeia grammata. Apart from the above-discussed interpretation found in Herodotus, ancient scholars connected phoinikeia grammata to the colour red and to the use of palm leaves as writing material:Footnote 22

Eὐφρόνιος δέ, ὅτι μίλτῳ τὸ πρότϵρον ἐγράφοντο, ὅ ἐστι χρῶμά τι φοινικοῦν· Ἐτϵωνϵὺςδὲ καὶ Mένανδρος, ἐπϵιδὴ ἐν πϵτάλοις φοινικϵίοις ἐγράφοντο· ἤ, ὅπϵρ κρϵῖττόν ἐστιν ϵἰπϵῖν, ὅτι φοινίσσϵται ὑπ’ αὐτῶν ὁ νοῦς ἤγουν λαμπρύνϵται.Footnote 23

Euphronius however says, because earlier they used to write with a red ochre called miltos [red lead: Plin. HN 33.115], which has a reddish colour; and Eteoneus and Menander [BNJ 783 F 5], because they used to write on palm leaves; or, a better explanation, because the mind is reddened by them, that is, is brightened.Footnote 24

The explanation that the expression refers to ‘red letters’ because they ‘reddened’ the mind fails to convince; could this be an addition of the scholiast himself, as suggested by Arnold Gomme?Footnote 25 The connection with red ink, however, has received some attention in modern scholarship.Footnote 26 Right between the two explanations connecting phoinikeia grammata to the colour ‘red’, it is mentioned that according to the authors Etenoneus and Menander the expression is related to the practice of writing on palm leaves. This explanation is also found in the lexicon of Photius and the Suda, the well-known Byzantine encyclopaedic work from the tenth century AD.Footnote 27 The entry Φοινικήια γράμματα in the Suda reads as follows:

Λυδοὶ καὶ Ἴωνϵς τὰ γράμματα ἀπὸ Φοίνικος τοῦ Ἀγήνορος τοῦ ϵὑρόντος· τούτοις δὲ ἀντιλέγουσι Κρῆτϵς, ὡς ϵὑρέθη ἀπὸ τοῦ γράφϵιν ἐν φοινίκων πϵτάλοις. Σκάμων δ’ ἐν τῇ δϵυτέρᾳ τῶν ϵὑρημάτων ἀπὸ Φοινίκης τῆς Ἀκταίωνος ὀνομασθῆναι. μυθϵύϵται δ’ οὗτος ἀρσένων μὲν παίδων ἄπαις, γϵνέσθαι δὲ αὐτῷ θυγατέρας Ἄγλαυρον, Ἔρσην, Πάνδροσον· τὴν δὲ Φοινίκην ἔτι παρθένον οὖσαν τϵλϵυτῆσαι. διὸ καὶ Φοινικήϊα τὰ γράμματα τὸν Ἀκταίωνα, βουλόμϵνόν τινος τιμῆς ἀπονϵῖμαι τῇ θυγατρί.

Lydians and Ionians [call] the letters [thus] from their inventor Phoinix the son of Agenor; but Cretans disagree with them, [saying that] the name was derived from writing on palm leaves. But Skamon in his second book on Discoveries [says] that they were named for Phoinike the daughter of Aktaion. Legend tells that this man had no male children, but had daughters Aglauros, Erse, and Pandrosos; Phoinike, however, died while still a virgin. For this reason, Aktaion [called] the letters Phoenician, because he wanted to give some share of honour to his daughter.Footnote 28

Likewise, in the scholia to Dionysius Thrax reference is made to writing on palm leaves alongside other explanations:

Tινὲς δέ φασι τοὺς χαρακτῆρας τῶν στοιχϵίων τοὺς παρ’ ἡμῖν ὑπὸ Ἑρμοῦ ἐν φοίνικος φύλλῳ γϵγραμμένους καταπϵμφθῆναι τοῖς ἀνθρώποις, διὸ καὶ φοινίκϵια λέγϵται τὰ γράμματα· οἱ δέ, ὅτι Φοινίκων ἐστὶν ϵὕρϵσις· οἱ δέ, ὅτι ὁ παιδαγωγὸς τοῦ Ἀχιλλέως ὁ Φοῖνιξ ἐφϵῦρϵν αὐτά.Footnote 29

Some say that the shapes of the elements which we use were transmitted to mankind by Hermes, written on a palm-leaf, which is why the letters are called phoinikeia; others however say they are a discovery of the Phoenicians; yet other, that the paedagogue of Achilles, Phoenix invented them.Footnote 30

In sum, several conflicting theories existed about the meaning of phoinikeia grammata. The ‘Phoenician’ interpretation advocated by Herodotus may have become the most popular, but it did not preclude other narratives, according to which the expression originally referred to ‘red letters’, or to writing on palm leaves. These alternative explanations stem from a much later time and should therefore be treated with caution, as they could be the result of later reinterpretations and/or inventions. By the same token, however, the fact that these theories are attested quite late, does not a priori make them false, nor does it exclude the possibility that they are in fact much older; it is generally agreed that the Suda and Photius preserve ancient knowledge, if often in garbled form. It is therefore worthwhile to reassess the primary attestations of phoinikeia grammata to see whether the alternative explanations may offer a more cogent interpretation than the commonly accepted narrative.

III. Phoinikeia grammata used to mean ‘Phoenician letters’ or ‘red letters’

Most attestations of phoinikeia grammata are found in scholia.Footnote 31 They mainly appear in discussions about the origin and meaning of this expression, some of which have been treated above. When examining the ‘primary’ usage of this expression, that is the ways in which it occurs in classical sources, it appears that the combination phoinikeia grammata was by no means standard; the noun γράμματα (or, alternatively, στοιχϵῖα) is usually used by itself, without the adjective φοῖνιξ, to refer to ‘letters’.Footnote 32 The same applies to the Latin expression litterae Punicae/Phoenicae. The addition of the adjective provided extra, significant information and its meaning depended on the context. Three main categories can be distinguished. First of all, in some instances, the adjective φοῖνιξ (Latin: punicus) has to be understood as an ethnikon, referring to ‘Phoenician/Punic’ letters. For example, Livy (28.46.16–18) relates that Hannibal erected an altar recording his deeds in both the Greek and Phoenician alphabets:Footnote 33

propter Iunonis Laciniae templum aestatem Hannibal egit, ibique aram condidit dedicavitque cum ingenti rerum ab se gestarum titulo Punicis Graecisque litteris insculpto.

Hannibal spent the summer near the temple of Juno Lacinia, and there he erected an altar and dedicated it with a very long record engraved in Punic and Greek characters, setting forth the achievements he had performed.Footnote 34

Likewise, when Cicero (106–143 BC) talks about litterae punicae (Verr. 2.4.103) in connection with the North African king Masinissa, he is referring to the contemporary alphabet used there. Upon discovering that they were stolen from a temple, Masinissa sent back some large teeth that were given to him, with an inscription:

itaque in iis scriptum litteris Punicis fuit regem Masinissam imprudentem accepisse, re cognita reportandos reponendosque curasse.

and there was engraved on them in Punic characters that Masinissa the king had accepted them imprudently; but, when he knew the truth, he had taken care that they were replaced and restored.

An example from a much later period is provided by Theophanes the Chronographer (ca. 752–818 AD), who describes two stelae in Libya inscribed with phoinikeia grammata by fugitives, referring to the contemporary Phoenician or Punic alphabet in use there at the time:

στήσαντϵς δύο στήλας ἐπὶ τῆς μϵγάλης κρήνης ἐκ λίθων λϵυκῶν ἐγκϵκολαμμένα ἐχούσας γράμματα Φοινικικὰ λέγοντα τάδϵ· ἡμϵῖς ἐσμέν οἱ φυγόντϵς ἀπὸ προσώπου Ἰησοῦ τοῦ λῃστοῦ, υἱοῦ Ναυῆ.Footnote 35

they erected two stelae at the large fountain made of white stone, containing carved Phoenician characters which read as follows: we are the fugitives from the face of the pirate Jesus, son of Nave.

Secondly, phoinikeia grammata may refer to ‘letters’ painted in red, as in the below passage from Cassius Dio (second–third century AD):

σημϵῖον δέ τι τῶν μϵγάλων, τῶν τοῖς ἱστίοις ἐοικότων καὶ φοινικᾶ γράμματα ἐπ’ αὐτοῖς πρὸς δήλωσιν τοῦ τϵ στρατοῦ καὶ τοῦ στρατηγοῦ σφων τοῦ αὐτοκράτορος ἐχόντων, ἐς τὸν ποταμὸν ἀπὸ τῆς γϵφύρας πϵριτραπὲν ἐνέπϵσϵ.Footnote 36

But one of the large flags that resemble sails with red letters upon them to distinguish the army and its commander-in-chief, was overturned and fell from the bridge into the river.Footnote 37

The third and, for the present investigation, most interesting category is made up of cases in which phoinikeia grammata refers to (very) ancient inscriptions.

IV. Phoinikeia grammata referring to ancient inscriptions

A well-known example of phoinikeia grammata referring to an ancient inscription is the lebēs inscribed by Cadmus, which features in the Lindian Chronicle. This fascinating document, which is written on a marble slab and dates to 99 BC, records the dedications made to the temple of Athena at Lindos before the destruction of the original temple in 392/1 BC. Among the votive objects from ancient times mention is made of a bronze lebēs of Cadmus, which was inscribed in phoinikika grammata, according to Polyzalus:Footnote 38

Κάδμος λέβητα χά[λ]κϵον φοινικικοῖς γράμμα-

σι ἐπιγϵγραμμένον ὡς ίστορϵῖ Πολύζα-

λος ἐν τᾶι Δ ταν ἱστοριᾶν.Footnote 39

Cadmus, a bronze lebēs. Inscribed with

phoinikika grammata as Polyzalus reports

in the fourth book of his Investigations. Footnote 40

The historian Diodorus Siculus (first century BC) also mentions this inscribed bronze lebēs of Cadmus in his description of Rhodes. Like the Lindian Chronicle, which may have been his source,Footnote 41 Diodorus explicitly mentions that the inscription is written in phoinikeia grammata (5.58.2):Footnote 42

ὁ δ’ οὖν Κάδμος καὶ τὴν Λινδίαν Ἀθηνᾶν ἐτίμησϵν ἀναθήμασιν, ἐν οἷς ἦν χαλκοῦς λέβης ἀξιόλογος κατϵσκϵυασμένος ϵἰς τὸν ἀρχαῖον ῥυθμόν· οὗτος δ’ ϵἶχϵν ἐπιγραφὴν Φοινικικοῖς γράμμασιν, ἅ φασὶ πρῶτον ἐκ Φοινίκης ϵἰς τὴν Ἑλλάδα κομισθῆναι.

Cadmus also honoured Lindian Athena with votive offerings, among which there was a bronze lebēs worthy of note, made in the archaic fashion. This had an inscription in phoinikeia grammata, which they say were brought first from Phoenicia into Greece.Footnote 43

Diodorus seems to take the expression phoinikeia grammata to refer to the alphabet, adding that the letters were apparently first introduced to Greece from Phoenicia. From the interjection ‘they say’, one can tell that for Diodorus this was not an established and undisputed fact, and he was probably aware of other explanations.Footnote 44

The assumption that phoinikeia grammata here refers to the alphabet, however, is not self-evident. The Lindian Chronicle lists several inscribed objects. Only in two cases is the type of script specified: in the above-quoted example and in the case of an inscription in Egyptian hieratic (ἱϵρὰ γράμματα) by the Egyptian donor Amasis.Footnote 45 The fact that the script is further defined implies that these two inscriptions are different from the others (which were presumably written in the Greek alphabet). Interestingly, they are also the only two inscriptions in the chronicle of which the content is not quoted. This could either mean that the compilers of the list could not read the inscriptions quoted by their source (Polyzalus in the case of the dedication of Cadmus), or that their content was not quoted by their source.Footnote 46 One could come up with several explanations for this, but an obvious one would be that the inscription could not be understood, because it was written in a different script. This explanation is appropriate for the Egyptian dedication, which was after all composed in foreign (hieratic) writing. What about the inscribed lebēs of Cadmus?Footnote 47 One could argue that the inscription was written in the Phoenician alphabet, which the compilers could not read.Footnote 48 This, however, leaves us with the problem that an alphabetic inscription was anachronistically associated with a hero from the Heroic Age.Footnote 49 The ‘Phoenician’ interpretation is even more challenging in the following example.

The expression punicae litterae is mentioned in the Latin version of the so-called Diary or Journal of Dictys of Crete. This is a document supposedly written by Dictys, the companion of Idomeneus in the Cretan contingent at Troy, containing an eyewitness report of the Trojan War.Footnote 50 It circulated in a Greek version in the late second century AD, of which some papyrus fragments have survived.Footnote 51 The Latin version, ascribed to the author Septimius (third–fourth century AD), is accompanied by a prologue (prologus) as well as a prefatory letter (epistula). The prologue is older than the letter and was probably translated from Greek.Footnote 52 In later editions, Septimius appears to have replaced this prologue by the prefatory letter.Footnote 53

The prologue opens by stating that Dictys, a Cretan by birth from the city of Knossos, was a contemporary of the sons of Atreus and an expert in the ‘Phoenician’ language and letters (peritus uocis ac litterarum Phoenicum). He wrote annals of the Trojan War in nine volumes on linden-wood tablets in phoeniceis litteris, which he ordered to be buried with him. After an earthquake in the 13th year of Nero’s reign, his tomb was laid bare and discovered by shepherds. They saw the linden-wood tablets, which were covered with writing that they did not recognize, and were subsequently brought to Nero:

haec igitur Nero cum accipisset aduertissetque punicas esse litteras harum peritos ad se euocauit, qui cum uenissent, interpretati sunt omnia. cumque Nero cognosset antiqui uiri, qui apud Ilium fuerat, haec esse monumenta, iussit in Graecum sermonem ista transferri e quibus Troiani belli uerior textus cunctis innotuit.

When, then, Nero had received them and recognized that they were in Phoenician script, he called in experts in this script, who arrived and explained everything. And when Nero realised this documented a man of long ago who had been at Troy, he gave instructions for it to be translated into the Greek language, as a result of which a truer account of the Trojan War became known to everyone.Footnote 54

The later letter (epistula) of Septimius, which possibly accompanied the second edition of the Latin version, gives a slightly different account:

pastores cum eo deuenissent, forte inter ceteram ruinam loculum stagno affabre clausum offendere ac thesaurum rati mox dissoluunt non aurum nec aliud quicquam praedae, se libros ex philyra in lucem prodituri. at ubi spes frustrata est, ad Praxim dominum loci eos deferent, qui commutatos litteris Atticis—nam oratio Graeca fuerat—Neroni Romano Caesari obtulit, pro quo plurimis ab eo donatus est.

Shepherds who arrived there [at the grave], by chance came upon a tin box among the other rubble. So, thinking it was treasure they presently opened it. But what came to light was not gold or anything profitable, but books of linden bark. As their expectations had been disappointed, they took them to Praxis, the master of the place, who transcribed them into Attic script—because it was in Greek—and took it to Nero, the Roman Emperor, in return for which he got many gifts.Footnote 55

Here, the documents are described as being written in Greek, but in a different script. Earlier in the letter, Septimius states that the text was written in litteris Punicis, which were introduced by Cadmus and Agenor and were quite widespread in the days of the Trojan War:

Ephemeridem belli Troiani Dictys Cretensis, qui in ea militia cum Idomeneo meruit, primo conscripsit litteris Punicis, quae tum Cadmo et Agenore auctoribus per Graeciam frequentabantur.

The Diary of the Trojan War was first written down by Dictys of Crete, who served in that campaign with Idomeneus, in Phoenician script, which in those days, thanks to Cadmus and Agenor, was widespread in Greece.Footnote 56

From the scantily preserved earlier Greek version a similar picture emerges: it is mentioned that the text was ‘transcribed’ (μϵταγραφῆναι, FGrH 49 T2c) after its discovery.Footnote 57 The papyrus fragment P.Oxy. 4944 appears to relate that the text was written in what were thought to be the letters of Cadmus and Danaus.Footnote 58

Though the diary enjoyed the status of an authentic and authoritative narrative (together with the diary of Dares) in the Middle Ages, modern scholarship views the existence and rediscovery of this ancient document as a fabrication. The adage that the more complex and specific the details of a text and its survival, the more they proclaim its falsity, probably holds true,Footnote 59 all the more because the Fundbericht shows all the formal features of ‘pseudo-documentarism’.Footnote 60 Since the ‘diary’ itself is held to be invented, some scholars dismiss the punicae litterae as fictitious, arguing that they do not refer to a historical, but rather a legendary script.Footnote 61 Though a healthy dose of distrust is certainly warranted, one should not too easily discard the account as mere fiction without any historical relevance. The primary aim of the Beglaubigungsapparat built around this text was to lend credibility to the fact that it was a truly ancient document, dating to the time before Homer. In order to achieve the desired ‘reality effect’, the physical details, the language and the script of the document (and its uncovering) had to sound convincing to the audience.Footnote 62 It has long been suggested that the report was inspired by genuine discoveries of ancient documents.Footnote 63

As for litterae punicae, they must have evoked an image in the minds of the audience, which was plausible in this particular context. Karen Ní Mheallaigh attempts to answer the question of what precisely the audience would have envisioned when hearing or reading about a document composed in litterae punicae. She assumes that the document that is described in the Latin prologue is not only written in Phoenician letters, but also in the Phoenician language, though the latter is never explicitly stated anywhere. She argues that readers were invited to think of Phoenician as the lingua franca in the heroic past. As for the fact that Septimius’ letter mentions that the text was in Greek (nam oratio Graeca fuerat), and thus not in Phoenician(!), she speculates that Septimius here replaced the ‘Phoenician original’ with a ‘culturally more palatable Greek version’ to accommodate the taste of the Roman audience. She admits that this solution is not very satisfactory, and wonders why, if this were the case, Septimius did not ‘expunge the Journal’s distasteful Punic pedigree entirely? It seems puzzling that Septimius should jettison the Phoenician language Ur-text, yet retain the fiction of its Phoenician writing’.Footnote 64 She solves this conundrum by suggesting that the ‘Punic letters’ represent a primitive form of the Greek alphabet, linking it to its gradual development, which is a slightly forced and not entirely consistent explanation.Footnote 65

The idea that litterae punicae must refer to an ancient form of writing is appealing, however, especially if one recalls the inscription ascribed to Cadmus discussed above. Phoinikeia grammata apparently represent a truly ancient script that was distinct from contemporary writing, that was believed to have been in use before and during the Trojan War and, if we attach any value to the remark in Septimius’ letter, that was used for the Greek language. These facts combined make it very hard, if not impossible, not to think of earlier proposals which, largely for entirely different reasons, link phoinikeia grammata to the Linear B script.Footnote 66 The ways in which the supposedly ancient Journal of Dictys is described (the fact that it dates to the time of the Trojan War; the fact that the herdsmen did not recognize its writing; the fact that it had to be transliterated and that it is in one account referred to as Greek, whereas in the other it is mentioned that it had to be ‘transcribed’ or ‘translated’ into (Classical) Greek) fit all the characteristics of the syllabic Linear B script, which was used for Mycenaean, an ancient dialect of Greek of the Late Bronze Age. Rather than a ‘puzzlingly, implausible Punico-Greek text’Footnote 67 from a fanciful fantasy world dominated by the Phoenician script and language, the alleged Journal of Dictys would instead represent a document written in an attested ancient script from a real historic past, which the audience rightly associated with the time of the Trojan War and before. As will be argued further in detail below (section VIII), there is ample evidence that the Greeks were aware of the existence of Late Bronze Age writing systems, either through archaeological discoveries and/or (orally) transmitted stories. The assumption that phoinikeia grammata refers to Linear B gains further strength if we look at other attestations of this expression, which are also clearly situated in the Heroic Age, such as the story of Palamedes.

Palamedes was a Greek hero, (probably) identified as Argive, who according to some traditions invented writing. He does not occur in the Homeric epics, but his legend is undoubtedly ancient. Palamedes plays an important role in the Cypria, where he is the one who uncovers the feigned madness of Odysseus. He also appears in the plays of Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides and Astydamas, and the works of various other authors.Footnote 68 In a scholion to Euripides’ Orestes, Palamedes is mentioned in connection with phoinikeia grammata. The scholiast asserts that Palamedes solved the Achaeans’ food rationing problem during the Aegean fleet’s stay at Aulis on their way to Troy by showing them phoinikeia grammata:

πρῶτον μὲν τὰ Φοινίκια διδάξας γράμματα αὐτοὺς ἴσην τϵ καὶ

ἀνϵπίληπτον τὴν διανομὴν ἐν τούτοις ἐπραγματϵύσατο.Footnote 69

First having taught them phoinikeia grammata, he concerned himself with the equal and correct allocations among them.

It need not be pointed out that the distribution of food is precisely the type of usage that is attested in the Linear B documents from the Late Bronze Age.Footnote 70 Unfortunately, we cannot be sure that the term phoinikeia was present in the original source, as it cannot be entirely excluded that these are the words of the scholiast. In any case, as in the above examples, phoinikeia grammata are again associated with the distant past.

Phoinikeia grammata are further mentioned in connection with the Trojan War in the Poimenes of Sophocles, which we know only from a fleeting reference in Hesychius.Footnote 71 Here, they seem to be mentioned in the context of the arrival of the Greeks at Troy. The occurrence of ‘Phoenician letters’ here has puzzled some scholars,Footnote 72 but it would be much less surprising in light of the interpretation suggested here, in which phoinikeia grammata refer to Linear B writing. We may further mention a fragment from Euripides’ Palamedes, in which the protagonist appears to defend his invention of writing:

τὰ τῆς γϵ λήθης φάρμακ҆ ὀρθώσας μόνος,

ἄφωνα φωνήϵντα συλλαβὰς τιθϵὶς,

ἐξηῦρον ἀνθρώποισι γράμματ҆ ϵἰδέναι.Footnote 73

On my own I established remedies for forgetfulness, which are without speech and (yet) speak, by creating syllables, I invented for mankind knowledge of writing.Footnote 74

The description of Palamedes’ invention as ‘creating syllables’ makes perfect sense if this is a reference to the Linear B script, which is of a predominantly syllabic nature, but is less evident if one takes it to refer to alphabetic writing. However, since the precise translation and reading of this passage is somewhat debated, this example should be treated with caution.Footnote 75 Last but not least, the interpretation of phoinikeia grammata as Linear B writing would elucidate a thus far opaque quotation from Timon cited by Sextus, which refers to phoinikika sēmata (‘Phoenician signs’).

V. Sēmata phoinikika

In the book Against Grammarians, Sextus Empiricus (second–third century AD) recounts the benefits of learning how to write and he counts literacy among one of the most useful things. He then remarks the following:

καίτοι δόξϵιϵν ἄν τισιν ἐπὶ τῆς ἐναντίας ϵἶναι προλήψϵως

ὁ προφήτης τῶν Πύρρωνος λόγων Tίμων ἐν οἷς φησι

γραμματική, τῆς οὔ τις ἀνασκοπὴ οὐδ’ ἀνάθρησις

ἀνδρὶ διδασκομένῳ Φοινικικὰ σήματα Κάδμου.Footnote 76

However, some might think that Timon, the spokesman for Pyrrho’s discourses, has the exact opposite preconception when he says: ‘Grammar, of which there is no consideration nor inspection by a man being taught the Phoenician signs of Cadmus’.Footnote 77

The quotation is attributed to Timon, who is known as the expounder of the work of the ‘sceptic’ Pyrrho of Elis (fourth–third century BC). Pyrrho does not appear to have written down anything himself, but his works were recorded by his pupil Timon. Most of them have been lost, and they are mainly preserved through the works of Sextus Empiricus. The above quotation is not otherwise recorded and we thus have no idea of its original context.Footnote 78 Sextus is clearly struggling with the interpretation of this seemingly contradictory saying of Timon. His deliberations are worth quoting in full:

But in fact, it doesn’t seem to be this way, for what he says, ‘there is no consideration nor inspection’, is not such as to go against literacy itself, by way of which ‘the Phoenician signs of Cadmus’ are taught, for if someone is being taught it, how has he not made it his business? Rather, he is saying something like this: ‘for the person who has been taught the Phoenician signs of Cadmus there is no business with any other grammar beyond this’, which tends not towards this grammar—the one that is observed in the elements and in writing and reading by means of them—being useless, but the boastful and busybody kind.

For the use of the elements bears directly on the conduct of life, but not to be satisfied with what is handed down from the observation of these, and to demonstrate in addition that some are by nature vowels and others consonants, and that of the vowels some are by nature short, others long and others two-timed, having length and shortness in common, and in general the rest of the stuff that the nonsense-filled grammarians teach—that is useless.Footnote 79

According to Sextus, Timon here does not agitate against literacy itself, but rather against boastful teachers.Footnote 80 As kindly pointed out to me by one of the anonymous reviewers, the explanation of Sextus should be understood in connection with the two types of grammar that are mentioned earlier in the text:

However, since grammar is of two kinds, one professing to teach the elements (στοιχϵῖοv) and their combinations and being something of a general expertise in reading and writing, the other being a deeper power than this, lying not in the bare knowledge of letters (γράμμα) but also in the examination of their discovery and their nature, as well as the parts of the discourse constructed from these and any other object of the contemplation of the same sort, it is not our task to argue against the first.Footnote 81

Timon’s remark should be seen as referring to the second kind of grammar. This is, however, not evident from the quotation itself, which refers to grammar in general. Another puzzling element of the quotation is that the word σήματα is used rather than expected γράμματα.

If one takes phoinikika sēmata to refer to Linear B writing, an elegant solution to these difficulties presents itself. First of all, it would explain the choice of the word ‘signs’ (σήματα) rather than ‘letters’ (γράμματα), which is a more adequate term to describe a logosyllabic than an alphabetic writing system.Footnote 82 More importantly, in this interpretation, the quotation suddenly becomes comprehensible and any apparent contradiction or ambiguousness dissolves. Timon’s argument is that literacy does not necessarily require extensive knowledge about vowel length, etc., as one could in the past manage with a logosyllabic writing system, which was unable to represent the relatively large number of phonemic distinctions of Greek. Sextus is right to conclude that Timon is not attacking literacy itself, but that he is militating against the (in his eyes) unnecessary phonetic rules taught by grammarians. To illustrate his point, he contrasts the alphabet to the (in this respect) much more defective logosyllabic Linear B writing system.

I am not implying that Timon or Pyrrho could actually read and understand Linear B, but I do hold it to be conceivable that they were aware of its existence, either through later discoveries of Linear B texts or through legends.Footnote 83 Similarly, the ancient Greeks were undoubtedly familiar with the concept of syllabic writing systems. Though the alphabet may have been the dominant script in Classical Greece, it was not the only writing system that was in use. In Cyprus, with which there were extensive contacts, the Cypriot syllabary, ultimately a descendant of Linear A, existed till the fourth century BC. Inscriptions in the Cypriot syllabary have turned up outside of Cyprus in various locations, including Lefkandi (Euboea), the northern Aegean (Chalcidice), southern Italy (Policoro, Broglio di Trebbesace), Sardinia and Delphi.Footnote 84 From the pictorial appearance of Linear B texts, one could easily derive that it had more in common with a syllabic than an alphabetic script (as implied by the choice of the word σήματα), and that it was a writing system with no, or little, regard for the kind of ‘stuff that the nonsense-filled grammarians teach’.

It is regrettable that we do not possess the original context of the quotation, but based on the available evidence, the above interpretation clarifies this otherwise enigmatic and seemingly self-contradictory phrase. At the same time, it eloquently demonstrates that to Sextus the original meaning of phoinikeia sēmata/grammata was completely lost, and that this knowledge certainly was not omnipresent in his time.

VI. Preliminary conclusions

The above overview has shown that the assumption that the expression phoinikeia grammata refers to the Phoenician origins of the Greek alphabet as suggested by Herodotus cannot be upheld. In some cases, its meaning is clear; it refers to the contemporary Phoenician or Punic alphabet or to letters painted in red. In the other examples discussed, the term phoinikeia grammata are is used in connection with ancient inscriptions and one may summarize their characteristics as follows:

-

they are connected to ancient documents believed to be from the time of the Trojan War and before;

-

they appear to represent a different script than the contemporary Greek alphabet (and usually cannot be read).

If we include the information that may be adduced from the attestations in Septimius’ epistula and the work of Sextus Empiricus, the following features may be added:

-

they were believed to represent a language related to (similar to, yet different from) Greek;

-

they seem to refer to syllabic writing;

-

they are thought to have represented fewer of the phonemic distinctions of Greek than the Greek alphabet.

The translations ‘red’ or ‘Phoenician’ do not adequately explain these characteristics, least of all the strong connection with the Heroic Age. It cannot be a coincidence that all these attestations of phoinikeia grammata refer to very ancient inscriptions, and never to contemporary texts. They must refer to an older script, which was distinctly different from the then current Greek alphabet. As it so happens, a different writing system that fits the above description, namely Linear B, was in use in Late Bronze Age Greece. This leaves us with two options: either the phoinikeia grammata in these cases consistently refer to a fictitious ancient writing system, which coincidentally shares all historical and formal characteristics of Linear B, or, applying Occam’s razor, they are in fact this Late Bronze Age script.Footnote 85 Following the proposal of Ahl, the adjective phoinikeia thus originally referred to palm leaves, which have long been suspected to have been the primary writing material for Linear B.Footnote 86

From at least the fifth century onwards, however, it was no longer common knowledge that the expression phoinikeia grammata referred to the Linear B script, and people like Herodotus instead connected it to early alphabetic writing, which he thought had been brought to Greece by the Phoenicians (hence ‘Phoenician letters’). His reinterpretation of the phoinikeia grammata as ‘Phoenician letters’ may have been triggered by ancient alphabetic inscriptions he saw at Thebes, combined with his admiration for the Phoenicians.Footnote 87 As a consequence, phoinikeia grammata also came to refer to (Archaic) alphabetic inscriptions. Some authors, however, were still aware of the term’s original meaning and used it to refer to Linear B writing.

The above scenario has two important ramifications, which might be conceived as problematic at first glance. First of all, it implies that the Linear B script was written on palm leaves. As mentioned above, this idea has been put forward before, but it has not found general acceptance. In contrast to Linear A, which is commonly believed to have been used on perishable materials,Footnote 88 there is no such consensus with respect to Linear B. Some scholars assume that Linear B must have been written on perishable material,Footnote 89 but others maintain that this script was restricted to writing on the more durable clay.Footnote 90 Secondly, taking phoinikeia grammata to refer to Linear B implies that in Classical Greece there was awareness of the existence and the appearance of this Late Bronze Age writing system, a statement which may raise some eyebrows. Since the palm leaves, inscribed or not, are now irretrievably lost and the minds of those living in ancient times are equally inaccessible, we have to rely on indirect evidence to substantiate these claims. Fortunately, there are sufficient data at hand to support the scenario proposed here. Let us first turn to the use of Linear B on perishable materials.

VII. In palmarum primo scriptitatum: evidence for palm-leaf writing from Linear B and later sources

The word φοῖνιξ is already attested in Linear B texts, where we find the noun po-ni-ke and the adjective po-ni-ki-jo/a.Footnote 91 Unfortunately, the contexts are not very helpful in determining the meaning of this word. The information provided by the ultra-brief texts is simply too limited to give a reliable translation. The word po-ni-ke refers several times to a decorative motif on furniture, where the most plausible meaning is ‘palm tree’.Footnote 92 As an adjective, it may also describe chariots and textiles, in which case it may mean ‘red’. It further occurs in combination with some sort of spice or condiment measured by weight. Here, it probably refers to dates from a date palm.Footnote 93 No clear connection between po-ni-ke/po-ni-ki-jo/a and writing has been attested, but this is hardly to be expected, considering the types of document at hand. Based on the available Linear B evidence, one can only conclude that it is highly likely that the word φοῖνιξ was already used to refer to palm trees in the Mycenaean Age.

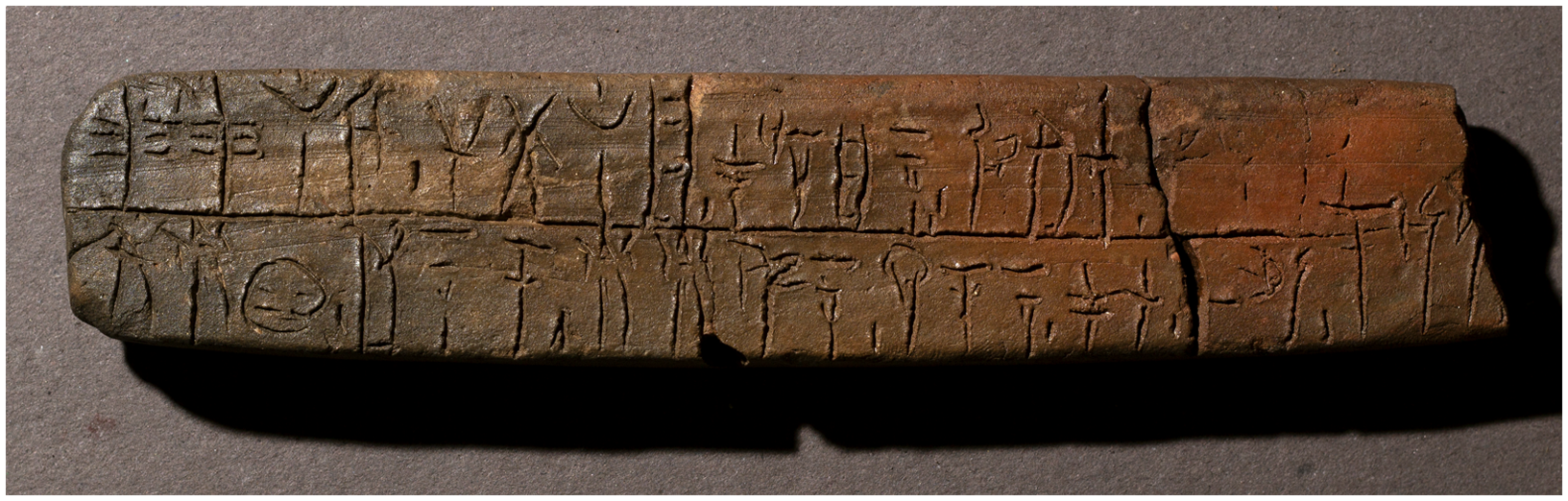

Though the Linear B texts may not offer direct evidence for the use of palm leaves for writing, they do present indirect evidence for the use of perishable writing materials. First of all, there is the format of the surviving Linear B texts on clay. As has long been pointed out, the shape of the most common type of Linear B tablets resembles the shape of palm leaves (see fig. 1). This tablet type has therefore been dubbed the ‘palm-leaf tablet’.Footnote 94 The choice of this tablet shape was deliberate; clay is a malleable substance and can be formed into all kinds of shapes and sizes (and other forms are also attested). An obvious explanation for why the clay was shaped into this form would be that it was imitating an already existing type of document, namely one written on palm leaves.Footnote 95

Fig. 1. Palm-leaf tablet from Pylos (PY Eb 1176), Courtesy of The Pylos Tablets Digital Project and The Palace of Nestor Excavations, The Department of Classics, University of Cincinnati.

Further, it has often been noted that the complex and curved forms of the Linear B characters are better suited to be written in ink with pen or brush than to be incised in the coarse material clay.Footnote 96 Alternatively, no ink was used, but palm leaves or ribs were incised with a stylus. As examples from South Asia show, this technique is very suitable for making round letters.Footnote 97 It is telling that the Linear B sign forms are retained over time without any simplification or abstraction, which would have made writing in clay considerably easier. By contrast, we do very clearly see such developments in the cuneiform script, which was written almost exclusively on clay. The most logical explanation for the unchanging complexity of the Linear B sign forms is that clay was not the primary writing material for this script, that it was mostly used on softer materials, such as palm leaves.

Another indicator for the use of Linear B writing on perishable material is the awkward ratio of the relatively high number of individuals who were involved in writing to the relatively few and short extant records. This imbalance would be explained if one assumes that writing was used on a much larger scale on perishable materials.Footnote 98 This would also account for the limited scope of these tablets. The surviving clay records only deal with local economic administration; texts of other genres are completely absent. However, contemporary Hittite texts indicate that the Aegean world participated in international diplomatic correspondence, which suggests that a more diverse textual corpus must have existed.Footnote 99 Whether they made use of their own writing system and/or the cuneiform script for this purpose is open to debate, but regardless of the type of script that was employed, it implies a wider use of writing than for the sole purpose of recording of local palatial administration.Footnote 100 Needless to say, the perishable materials used for writing were not necessarily restricted to palm leaves; perhaps they also made use of other ephemeral materials, such as leather, parchment, papyrus or wood, for more elaborate compositions.Footnote 101

From a global perspective, the choice of leaves, as well as other parts of trees such as wood or bark, as a primary writing material is nothing exceptional (fig. 2). Trees have been, and still are, a very common source of writing materials in many regions of the world.Footnote 102 The popularity of leaves is reflected in today’s terminology for script bearers in many languages (for example, folia, Blatt, hoja, feuille, ‘leaf’, etc.). When the Linear B scribes, who were accustomed to writing on palm leaves, happened to write on clay, they stuck to the same scribal conventions, including the shape of the documents.Footnote 103

Fig. 2. Palm midrib with incised alphabetic inscription from Yemen (L024), 11th-10th c. BC, Courtesy of Stichting Oosters Instituut, Leiden University Libraries. Photograph: Wim Vreeburg.

Confirmation of the practice of writing on palm leaves is found in later sources, such as Photius and the Suda.Footnote 104 It is also mentioned by Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD) in his Historia naturalis. Pliny (HN 13.21), citing Varro, relates that the use of papyrus for writing was invented in Alexandria, and that before that time, people wrote on other writing materials, including palm leaves. Varro informs us that paper owes its discovery to the victorious career of Alexander the Great, and his founding of Alexandria in Egypt:

antea non fuisse chartarum usum: in palmarum foliis primo scriptitatum, dein quarundam arborum libris. postea publica monumenta plumbeis uoluminibus, mox et priuata linteis confici coepta aut ceris; pugillarium enim usum fuisse etiam ante troiana tempora inuenimus apud Ηomerum.

[B]efore that period paper had not been used, the leaves of palms having been employed for writing first, and after that the bark of certain trees. In succeeding periods, public documents were inscribed on sheets of lead, soon private memoranda were also impressed upon linen cloths, or else engraved on tablets of wax; indeed, we find it stated in Homer, that tablets were employed for this purpose even before the time of the Trojan War.

Though Pliny’s sense of chronology leaves much to be desired (the invention of papyrus of course occurred long before Alexander the Great), the existence of the writing materials that he lists is confirmed by archaeological evidence and/or other sources. With respect to the practice of writing on leaves, further evidence is provided by Diodorus Siculus. This historian not only informs us about the grammata phoinikeia on the lebēs of Cadmus (see above, section VI), but also about the use of leaves (πέταλα) as writing material, in this case in Sicily. In book 11, he mentions in passing the phenomenon of petalism (πϵταλισμός) in Syracuse, a banishment practice similar to ostracism in Athens (11.87.1–3):

Now among the Athenians each citizen was required to write on a potsherd (ostrakon) the name of the men who, in his opinion, was most capable through his influence of tyrannizing his fellow citizens; but among the Syracusans the name of the most influential citizen had to be written on an olive leaf (πέταλον ἐλαίας), and when the leaves were counted, the man who received the largest number of leaves had to go into exile for five years … Now while the Athenians called this kind of legislation ostracism, from the way it was done, the Syracusans used the name petalism (πϵταλισμόν).Footnote 105

Olive leaves are obviously quite small, but since only a name needed to be jotted down, they would have sufficed for this particular purpose. Though referring to a later period, this attestation is a meaningful example of the use of leaf writing in the Greek-speaking world, as already noted by Ahl.Footnote 106

VIII. Greek awareness of their written past

The interpretation of phoinikeia grammata suggested above implies that in Classical times, at least in some circles, there was awareness of the existence of Linear B, and possibly other writing systems in the Aegean in the past. One only has to think of Arthur Evans’ observation that as late as the early 20th century Cretan women were wearing Linear B tablets that they had found as charms, to realize that in Classical times similar discoveries of Late Bronze Age writing were undoubtedly made.Footnote 107 There is in fact textual evidence to support this claim. The fabricated story of the rediscovery of the Journal of Dictys discussed above (section IV) appears to have been based on actual discoveries.Footnote 108 A somewhat similar report relates the discovery of an ancient document in the tomb of Alcmene, the mother of Heracles, of which Alain Schnapp has remarked that ‘it does not take too much imagination for today’s archaeologists to recognize a Mycenaean burial’.Footnote 109 When the grave was opened, a bronze tablet with a long inscription in an unknown script was revealed. A detailed account is given in the Moralia of Plutarch (46–120 AD). In the following passage, Phidolaus writes about the opening of the grave:

In front of the monument there lay a bronze tablet full of strange and certainly very ancient letters (γράμματα πολλὰ θαυμαστὰ ὡς παμπάλαια), for nobody could make anything of them, even though once the bronze was washed they were very clearly visible; their form was particular and strange, resembling very much that of Egyptian characters. Agesilaus accordingly, as the story goes, sent copies to the king (of Egypt), requesting him to show them to the priests to see if they could interpret them.Footnote 110

It has been suggested that the mysterious signs on this tablet, which look like Egyptian hieroglyphs, correspond to Linear B.Footnote 111 Yet another mention of the discovery of ancient documents are the bronze tablets dug up by the father of the historian Acusilaus of Argos, which supposedly served as the source for his Genealogies.Footnote 112 Further references to ancient inscribed objects include a remark in Ampelius’ Liber Memorialis (8.5) about litterae Palamedis that were deposited in the temple of Apollo at Sicyon together with other ancient heirlooms, such as the shield of Agamemnon,Footnote 113 and a pillar with ancient characters in the Mirabilia of Pseudo-Aristotle.Footnote 114 Though such discovery stories, like the Fundbericht of the Diary of Dictys discussed above, may reflect a literary topos rather than historical reality, and the ancient finds described may not be ‘real’ in the sense that it was not the actual tomb of Alcmene that was unearthed and the aforementioned shield did not really belong to Agamemnon,Footnote 115 they could nonetheless be based on genuine discoveries of objects and remains of earlier times. The ancient Greeks were regularly confronted with the physical reality of their (heroic) past, in the form of tombs, ruins, pictures and ancient artefacts.Footnote 116 Some of these remains were, rightly or wrongly, used as evidence to prove the historicity of Homer’s epics and the Trojan War, showing how much importance the Greeks (and Romans) attached to seeking out their glorious past.Footnote 117 The value attributed to relics of the Heroic Age was such that it even led to the creation of forgeries.Footnote 118

Apart from physical discoveries of Late Bronze Age writing, there are also numerous literary references to writing in the heroic past. As shown above (section IV), phoinikeia grammata appear several times in the context of the Trojan War and before. Apart from the examples discussed above, there are more literary texts, especially tragedies, that make mention of the use of writing in this period.Footnote 119 In these cases, however, it is not stated that this was done in phoinikeia grammata and in some cases it is evident that not Linear B, but alphabetic writing is implied.Footnote 120 When reviewing the numerous references to writing in the Heroic Age, Patricia Easterling rightly observes that writing in the distant past was apparently not seen as anachronistic. She draws attention to the striking contrast between the frequent use of writing in the Heroic Age in tragedy and the Homeric model, in which writing does not play a vital part.Footnote 121 The alleged opposition between the tragedians and Homer with respect to allusions to writing in the Heroic Age may not be as significant as it appears, however, and may even be non-existent. References to writing in Homer may be scarce, but they are not entirely absent. The most famous and unambiguous example is the episode in Il.6 about the hero Bellerophon, who unknowingly carries and delivers his own death warrant written by his father-in-law Proitus. As argued by Jenny Strauss Clay, the episode in Il. 7.87–91, when Hector imagines an epitaph to his glory, also implies a knowledge of writing. Further, there is a possible reference to writing in Il. 7.175–89.Footnote 122

Unfortunately, the significance of the seemingly limited role of writing in the Iliad has been grossly overstated and misinterpreted. It has been taken as evidence that Homer himself was illiterate, or that writing was deliberately suppressed in the epic, whereas the most obvious explanation is much more prosaic: writing does not feature prominently because this skill is not particularly pertinent to an heroic epic about war. The observation made by Nathaniel Schmidt over a century ago has lost none of its relevance:

A careful perusal of works such as Apollonius’ Argonautica, Vergil’s Aeneid, Lucian’s Pharsalia, Silius’ Punica, Statius’ Thebaid, Tasso’s Gerusalemme Liberata, Camoens’ Lusiadas, Milton’s Paradise Lost, the Mahabharata, the Ramayana, the Kalevale, with a view to discovering allusions to writing, brings home to the conviction that epic poets, excogitating their verses, pen in hand, very rarely think of mentioning the art they so constantly practice.Footnote 123

The fact that there are few references to writing in the Iliad is thus not necessarily due to conscious avoidance or downplaying, nor to the fact that Homer himself and/or the world he wanted to describe was illiterate, but simply because there was no need or motivation to refer to this mundane activity, except in the case of the Bellerophon episode, where the written message constitutes a crucial element of the story. The limited role of writing in Homeric epic is just as insignificant as the fact that no cats are mentioned in the Bible, and their nonappearance can hardly be used as evidence for the absence of script, or domestic felines, in certain time periods.

IX. σήματα versus γράμματα

Though the references to writing in Homer may be scant, the terminology used is of great significance. In the Bellerophon passage in Iliad book 6 just mentioned, Proitus writes down many ‘baleful signs’ (6.169: σήματα λυγρὰ) on a tablet (6.170: γράψας ἐν πίνακι). Bellerophon is asked to show the message (6.176: σῆμα) to his host. Later on, this message is described as ‘horrible᾽ (6.178: σῆμα κακὸν). Homer consistently uses the word σῆμα rather than expected γράμμα or στοιχϵῖοv to refer to writing.Footnote 124 The word σῆμα also occurs in another possible reference to writing in book 7.Footnote 125 The scene runs as follows. When the heroes have to decide who is to be the one to fight Hector (7.175–89), each man marks his lot (κλῆρον ἐσημήναντο ἕκαστος) and casts it into the helmet of Agamemnon. Nestor subsequently shakes the helmet and the lot of Ajax leaps out. Next, the herald walks around in the crowd, showing the lot to all the chieftains of the Achaians. None of them recognizes it (7.185: οἳ δ᾽ οὐ γιγνώσκοντϵς ἀπηνήναντο ἕκαστος). When the herald finally reaches Ajax, he places the lot in his hand, whereupon Ajax recognizes the token as his own and rejoices (7.189: [Aἴας] γνῶ δὲ κλήρου σῆμα ἰδών, γήθησϵ δὲ θυμῷ).

This passage can be, and has been, interpreted in various ways.Footnote 126 It could be the case that the heroes each marked their lot with a personal sign that was unrelated to writing and that was meaningful only to themselves, or perhaps with an impression of their personal seal. In this case, none of the heroes, except for Ajax, would have known to whom the winning lot belonged, unless of course they were familiar with each other’s personal signs or seals. Alternatively, the heroes do make use of writing, each jotting down (part of) their name. In this interpretation, everyone who sees the lot instantly understands that it belongs to Ajax, and the remark that they do not recognize it (οὐ γιγνώσκοντϵς) would indicate that they do not recognize it as their own. The lot is thus not shown to all in search of its rightful owner, but so that everyone can see for himself to whom it belongs and that there has been no foul play. Accordingly, the fact that it is first shown to all the others, and only then handed over to Ajax, is not a coincidence. An interesting parallel from later times is provided by the practice of inscribing with a letter lots, which were also shown around for inspection.Footnote 127

Though the second example may be ambiguous, the σήματα of the message of Proitus in book 6 without doubt refer to writing. In section V it has been suggested that the use of the word σῆμα by Timon refers to Linear B writing. In light of the evidence presented above, this is also the most obvious and logical interpretation of the signs foretelling Bellerophon’s death.

According to LSJ, the word γράμμα, ‘that which is drawn’, can refer to letters and messages, but also to pictures and marks. The principal meanings of σῆμα are ‘mark’, ‘omen’ or ‘token’. It can, for instance, be used for a mark on an animal’s head, signs from heaven, heavenly bodies, or a sign by which a grave is known.Footnote 128 If one accepts that σῆμα in the above cases refers to Linear B, its usage would be comparable to our modern use of the word ‘sign’ (Zeichen, teken, signe, etc.) to denote the elements of pictorial, logosyllabic writing systems, such as Linear B. Like σῆμα, γράμμα can also refer to marks, signs or pictures, but, unlike σῆμα, it can in addition refer to letters, that is, the elements of the alphabet. In other words, γράμμα can refer to both logographic/syllabic and alphabetic writing systems, and σῆμα only to the former.

X. Rediscovery or continued tradition?

Based on the available material, it cannot be established with certainty whether the allusions to writing in the Late Bronze Age are to be seen as later projections triggered by discoveries of ancient texts in Classical times, or as reflections of a continued tradition of ancient legends in which writing played a part. In light of the growing evidence pointing to continuity between the Late Bronze Age and the Early Iron Age, and the fact that Greek historians themselves saw no breach between the Heroic Age and their own era,Footnote 129 I would certainly not exclude the latter, but the former scenario might be more palatable to most. Obviously, the two scenarios are not mutually exclusive, but could rather reinforce each other.

Perhaps more controversial is the question of whether these ancient texts could still be read and understood. This idea was radically dismissed by John Forsdyke, who stated that all knowledge of Minoan and Mycenaean scripts was completely lost and claimed that ‘it is also certain that the historical Greeks could not read nor even recognise the prehistoric scripts’.Footnote 130 As already remarked by Hagen Biesantz, who holds a more nuanced and positive view, however, Forsdyke’s claim cannot be substantiated, and there are no grounds for assuming that no knowledge of the script of the ancestors had been preserved anywhere by anybody.Footnote 131

Indeed, though it may well be too optimistic to assume that actual knowledge of Linear B survived, it is also unfair to categorically deny all ancient Greeks any historical understanding of their written past. Of particular significance is the account in the Mirabilia (Pseudo-Aristotle) about an ancient pillar with ancient characters, which is brought to the Ismenium at Thebes, already briefly referred to above:

In the country called Aeniac, in that part called Hypate, an ancient pillar is said to have been found; as it bore an inscription in archaic characters (ἐπιγραφὴν ἀρχαίοις γράμμασιν) of which the Aenianes wished to know the origin, they sent messengers to Athens to take it there. But as they were travelling through Boeotia, and discussing their journey from home with some strangers, it is said that they were escorted into the so-called Ismenium in Thebes. For they were told that the inscription was most likely to be deciphered there, as they possessed certain offerings bearing ancient letters similar in form. There, having discovered what they were seeking from the known letters, they transcribed the following lines.Footnote 132

It is intriguing that the ancient inscribed pillar mentioned is eventually brought to the Ismenium of Thebes to be deciphered, the same location where Herodotus claims to have seen inscriptions in ‘Cadmeian letters’ and, much later, Pausanias (ca. 110–180 AD) reportedly saw an ancient, presumably inscribed, tripod dedicated to Heracles.Footnote 133 It is a tantalizing thought that this sanctuary not only housed ancient inscribed objects, but also experts with specialized knowledge of these inscriptions.Footnote 134 Due to the lack of more solid evidence (the Mirabilia may indeed not be the most reliable of sources), however, this claim cannot be substantiated. Likewise, the reference to the translation of the ancient bronze tablet mentioned in Plutarch’s Moralia by specialists in Egypt should be taken cum grano salis. Footnote 135 For the moment, one can only cautiously conclude that some strata of the population at least knew of the existence of Linear B (and possibly other Late Bronze Age writing systems), and that in some highly specialized circles, such as the Ismenium at Thebes, rudimentary knowledge about its basic characteristics was present. As already mentioned above (section V), the continued existence of a syllabic writing tradition at Cyprus, which was a derivative of Linear A, makes it conceivable that there was awareness, or at least suspicion, of the fact that the Linear B script was (logo)syllabic rather than alphabetic. This distinction is made explicit in the terminology used by authors like Homer and Timon (apud Sextus Empiricus), who referred to Linear B as ‘signs’ (σήματα) rather than ‘letters’ (γράμματα).

Either way, be it the result of later projections or of continued tradition, to the minds of the ancient Greeks the Heroic Age was a literate period. This is clear from the references to writing in tragedies situated in the Trojan War period, as well as from the fact that all narratives about the invention of writing are placed in the Heroic Age. In some cases (though certainly not all), the kind of writing that was used in ancient times is specified, and referred to as phoinikeia grammata (or Pelasgic/Palamedian/Cadmeian letters), implying a dissimilarity with the contemporary writing system. This is all hardly surprising, since a different writing system was in use in the Late Bronze Age, and samples of this ancient script did survive and were known in later times.Footnote 136

XI. Pelasgic letters

The interpretation of phoinikeia grammata suggested here may also shed light on the intriguing expression ‘Pelasgian’ or ‘Pelasgic’ letters. The term ‘Pelasgians’ (Πϵλασγοί) was used by classical authors to refer to the ancient inhabitants of Greece, in the times before the Trojan War.Footnote 137 The term ‘Pelasgic letters’ first appears in Dionysius Scytobrachion (third century BC), whose works included a history of the Trojan War.Footnote 138 His account of the development of the Greek alphabet is quoted by Diodorus and runs as follows:

Φησὶ τοίνυν παρ’ Ἕλλησι πρῶτον ϵὑρϵτὴν γϵνέσθαι Λίνον ῥυθμῶν καὶ μέλους, ἔτι δὲ Κάδμου κομίσαντος ἐκ Φοινίκης τὰ καλούμϵνα γράμματα πρῶτον ϵἰς τὴν Ἑλληνικὴν μϵταθϵῖναι διάλϵκτον, καὶ τὰς προσηγορίας ἑκάστῳ τάξαι καὶ τοὺς χαρακτῆρας διατυπῶσαι. κοινῇ μὲν οὖν τὰ γράμματα Φοινικήια κληθῆναι διὰ τὸ παρὰ τοὺς Ἕλληνας ἐκ Φοινίκων μϵτϵνϵχθῆναι, ἰδίᾳ δὲ τῶν Πϵλασγῶν πρώτων χρησαμένων τοῖς μϵτατϵθϵῖσι χαρακτῆρσι Πϵλασγικὰ προσαγορϵυθῆναι.

He says then that among the Greeks Linus was the first to discover the rhythms and song, and when Cadmus brought from Phoenicia the letters, as they are called, Linus was again the first to transfer them into the Greek language, to give a name to each character, and to fix its shape. Now the letters, are officially called ‘Phoenician’ because they were brought to the Greeks from the Phoenicians, but unofficially, because the Pelasgians were the first to make use of the transferred characters, they were called ‘Pelasgic’.Footnote 139

It is unclear how one should understand κοινῇ and ἰδίᾳ in this context and several different proposals have been made. The Loeb translation of Charles Henry Oldfather (followed by Paola Ceccarelli) suggests that the letters ‘as a group’ are called ‘Phoenician’ and ‘as single letters’ are called Pelasgic.Footnote 140 Ní Mheallaigh prefers ‘commonly’ vs ‘privately’,Footnote 141 and Jeffery translates ‘officially’ and ‘unofficially’ (the interpretation chosen here).Footnote 142 An exhaustive discussion is given by Aldo Corcella, who suggests that to Dionysius the ‘Phoenician’ letters are the alphabet in general, and the ‘Pelasgic’ ones relate to the first ‘Greek’ alphabet which was created by Linus based on the Phoenician alphabet introduced by Cadmus, thus reconciling different traditions.Footnote 143 Creative as these interpretations may be, none of them yields a satisfactory result and the account of Dionysius fails to persuade. Jeffery convincingly concludes that his ‘ill-fitting explanation’ shows that the phenomenon of ‘Pelasgic letters’ was not an invention of Dionysius himself, but that he is rather struggling with two already existing terms.Footnote 144

The quandary vexing Dionysius would be easily solved, however, if one took the phoinikeia grammata and Pelasgic letters to refer to Linear B writing. The most common way (κοινῇ) to refer to this script was connected to its primary writing material, palm leaves (phoinikeia grammata). In addition, there was a less frequently used term (ἰδίᾳ) that referred to the users of this script, the Pelasgians. This term was probably not used by the users of Linear B themselves, but rather a later designation.Footnote 145 In Classical times, both of these terms were in use by the Greeks to refer to the script of their ancestors, thus distinguishing this ancient writing system from their own contemporary alphabetic writing, to which they simply referred as grammata (or stoicheia). Over time, however, the original meaning of phoinikeia grammata came to be misunderstood (as explained above) and the expression was linked to alphabetic writing. A similar fate befell the expression ‘Pelasgic writing’, undoubtedly because the existence of Linear B writing was no longer common knowledge. Subsequently, one was faced with the awkward situation that two very different, mutually exclusive ethnika, ‘Phoenician’ and ‘Pelasgic’, came to refer to the same script, the Greek alphabet, a riddle that Dionysius failed to resolve convincingly. Ní Mheallaigh concludes that ‘Dionysius’ imaginary palaio-literary landscape was … generously littered with Greek texts written in these so-called “Phoenician” or “Pelasgic letters” which the scholar seems to have taken some trouble to accommodate to the Greek alphabet’.Footnote 146 In the scenario proposed here there is nothing fictional about this literary landscape; the terms ‘Phoenician’ and ‘Pelasgic’ letters reflected the memory of the use of Linear B in the Late Bronze Age, but this was no longer recognized by Dionysius and many of his colleagues.

XII. ‘On the malice of Herodotus’

The reliability, or lack thereof, of Herodotus has been a much-discussed topic since antiquity.Footnote 147 As demonstrated above (section I), there is ample reason to question his account of the introduction of the alphabet. Apart from the obvious chronological difficulties, the explanation offered by Herodotus is also not particularly cogent from a semantic perspective. When taking over a writing system, it is not uncommon that the recipient party borrows the terminology used for writing in the source language. If we think of the ancient Near East, for example, we see that the Sumerian terminology for ‘tablet’ and ‘scribe’ are taken over by Akkadian speakers who adopted this script. Likewise, the Chinese term hanzi was taken over in Japanese (kanji) and Korean (hanja) together with the Chinese writing system. It is, however, less self-evident that the writing system would be named after the people who introduced it.Footnote 148 The use of the ethnikon ‘Phoenician’ would make sense if the writing system were contrasted to an already existing one (compare, for example, the modern use of ‘Arabic’ versus ‘Roman’ numerals), but this does not seem to be applicable here. Alternatively, ethnika may be used to designate certain (erotic) acts or customs that clash with, or are different from, local rules, a practice that is still common today (for example, ‘French kissing’, ‘Russian style’, ‘going Dutch’). In Classical Greek, the verb φοινικίζω, ‘to be like a Phoenician’ referred to (homo?)sexual behaviour that was deemed inappropriate.Footnote 149 For an activity like writing (if not juxtaposed to a local system!), however, such an ethnic label would be highly exceptional. If one accepts Herodotus’ Phoenician interpretation, the implication is that the Greeks initially saw alphabetic writing as something highly outlandish and exotic. This is scarcely credible, considering their long-standing contacts with literate peoples, as well as their own writing traditions of more than half a millennium. The interpretation proposed here is much more plausible; it is not exceptional that writing systems are named after the (primary) writing material. A nice parallel is provided by the Lontara script, whose name is derived from the Malay word for palmyra palm (lontar), of which the leaves were used for writing.

The explanation of Herodotus should first and foremost be seen as a product of his time, and valued as such. His interpretation of phoinikeia grammata is reminiscent of his observations about ‘correct naming’. In a number of instances Herodotus mentions specifically whether a certain name is ‘correct’ (ὀρθῶς) or not. He considers a name to be correct when it signifies something important and accurate about the essence of the object or the individual.Footnote 150 Herodotus was not unique in this respect; correct naming was a fashionable interest in the fifth century. With respect to the ‘Phoenician letters’, Herodotus states that it is only ‘right’ that the Greeks named their alphabet after the Phoenicians (ὥσπϵρ καὶ τὸ δίκαιον ἔφϵρϵ), as they were the ones who introduced it to Greece.

As shown by Gomme, however, Herodotus and other logographers were prone to ‘correct’ certain traditions in light of their own theories and research abroad.Footnote 151 Herodotus had a clear preference for assuming foreign, usually Egyptian, origins and the Phoenicians often acted as intermediaries. He evidently admired the Phoenicians, which becomes apparent in the story about the digging of the Athos canal (7.23), where he praises their superior skills. A theory about the Phoenicians as bringers of the alphabet would certainly have appealed to him. Whether this theory was his own creation or was already in existence, to Herodotus’ mind, the best explanation for the expression phoinikeia grammata was that they were ‘Phoenician letters’, referring to the Phoenician origins of the Greek alphabet. Confirmation of the correctness of this view was easily found in the fact that the Greek and Phoenician alphabets were clearly related, as well as in the ubiquitous Phoenician presence throughout the Mediterranean in the fifth century BC, which undoubtedly strengthened Herodotus’ conviction that they must have played a crucial rule in the spreading of the alphabet. Seen in this context, the ‘Phoenician’ reanalysis of the adjective phoinikeia seems only logical, and explains its popularity. Quite possibly, the process of ‘Phoenicianization’ did not stop at the introduction of writing, but also affected the origins of the hero Cadmus.

XIII. Cadmus the Mycenaean or the Phoenician?

The role of the legendary Cadmus in the introduction of writing to Greece is much discussed.Footnote 152 The genealogy of this hero is not straightforward and many variants existed.Footnote 153 From the fifth century onwards, Phoenicia is mostly said to be his country of origin, though some accounts connect him to Egypt. Simultaneously, he was also generally believed to be a descendant of the Argive heroine Io.Footnote 154 Interestingly, there is no explicit mention of his foreign origins before the fifth century; in the earliest sources Cadmus is portrayed as a typical ‘Greek’ hero.Footnote 155 In modern scholarship his Oriental roots have therefore been questioned.Footnote 156 One of the most influential scholars to do so was Gomme, who, after examining the chronological development of the story of Cadmus from the literary sources, suggested that the Phoenician origins of Cadmus were not part of ancient tradition, but originated as a learned theory of logographers:Footnote 157

I would then emphasize the fact that it is not till the fifth century that we hear of the Phoenician theory, or of the connexion between Cadmus and Europa—the two cardinal points of the later story;—and suggest that the silence of Pindar and Aeschylus, and perhaps of Sophocles, the insistence of Herodotus and Euripides, and the curious variants in Pherecydes, may be significant, and mean that the theory has not long been formulated, nor as yet universally accepted.Footnote 158