1. INTRODUCTION

A common belief in second language acquisition is that naturalistic contexts favour the acquisition of sociolinguistic and pragmatic competence. Living in a native speech community is believed to offer more opportunities for real contact with native speakers and consequently more exposure to variation patterns than learning in the classroom does (Regan, Howard and Lemée, Reference Regan, Howard and Lemée2009; Gautier and Chevrot, Reference Gautier, Chevrot, Mitchell, McManus and Tracy-Ventura2015). Indeed in L2 French, many studies have shown that an increasing amount of input during a study abroad leads to the emergence of informal variants like the pronoun on (we), the deleted variant of the third pronoun singular i (he), the single post verbal negator pas (Armstrong, Reference Armstrong1996; Dewaele and Regan, Reference Dewaele2002; Lemée Reference Lemée2002). Results are similar for the use of the realization of speech acts like requests in L2 Spanish (Pinto, Reference Pinto2005; Shively, Reference Shively2011), in L2 German (Barron, Reference Barron2003) or L2 French (Holttinen, 2017). These studies show that stay in the target-language community leads to a change in the use of strategies. Learners at the beginning of a stay abroad resort to more direct strategies. The use of direct strategies often shifts to the use of indirect strategies at the end of the stay.

Our goal is to analyse the use of request perspectives by 24 Ghanaian learners before and after stay in France and Benin by means of an open role-play test. Making enquiries from strangers, asking for directions from strangers, asking for assistance from a friend, asking to borrow a book are just a few activities that make up the life of a student/year-abroad student. This study examines the choice of request perspective in situations addressing strangers and those addressing friends for both L1 and L2 speakers. A language-socialization paradigm argues that through day-to-day social interaction with native speakers, L2 learners begin to learn the rules of pragmatically appropriate L2 use (Duff, Reference Duff, Duff and Hornberger2008). The study thus relates individual interaction in French outside the classroom to the use of request perspectives. While it is now more common in L2 pragmatics to make use of discourse completion tests and pragmatic judgment tests, thus not getting L2 speakers’ actual production of speech acts, we decided to use an open role-play test to investigate spoken performance.

To the best of our knowledge, there is no work focused mainly on the effect of stay abroad on the use of request perspectives in French. The present study will thus contribute to our knowledge of the extent to which pragmatic assessment by an open role-play makes us understand how study abroad affects use of request perspectives.

2. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

2.1. Requests and Request Perspectives

Following Searle’s (Reference Searle1969) classification of illocutionary acts; requests are categorized as directives, which are considered as attempts by the speaker to get the hearer to do an act (Searle, Reference Searle1969:66). On such grounds, a request has been defined as a directive speech act in which the speaker asks the hearer to perform an action that is very often for the exclusive benefit of the speaker (Trosborg, Reference Trosborg1995). Requests are therefore considered to be potentially threatening for the addressee’s negative face, which is the individual’s need to have his/her freedom of action unimpeded (Brown and Levinson, Reference Brown and Levinson1987: 61).

In order for a successful interaction to be accomplished and the avoidance of threatening the face of one’s interlocutor, there’s the need for pragma-linguistic and socio-pragmatic knowledge on the part of the users. Thus, the requester needs to possess both knowledge of the linguistic resources for formulating a request in a particular language and knowledge of the contextual and sociocultural variables that render a particular pragma-linguistic choice appropriate in a particular speech situation.

According to Blum-Kulka et al. (Reference Blum-Kulka, House and Kasper1989) and Trosborg (Reference Trosborg1995), requests consist of two main parts; the core request or head act and the peripheral modification devices. The head act consists of the main utterance that has the function of requesting and can stand by itself.

Three main types of request-head-act realization are acknowledged in the literature: direct (e.g. Clean up the kitchen!), conventionally indirect (e.g. Could you clean up the kitchen?) and non conventionally indirect (e.g. The kitchen needs some cleaning) (Blum-Kulka and Olshtain Reference Blum-Kulka and Olshtain1984:200). In addition to variation in the directness level of a request, speakers can use request perspectives to mitigate the illocutionary force of the request.

Blum-Kulka and Olshtain (Reference Blum-Kulka and Olshtain1984:203) postulate that:

“The head act of a request can be realized from different points of view in making a request. A speaker will have different choices to realize a request and this choice depends on the situation. Many request realizations include reference to the requestor (‘I’ the speaker), the requestee (‘you’ the hearer), and the action to be performed. The speaker might choose different ways to refer to any of these elements, manipulating by his or her choice of request perspectives”.

Blum-Kulka and Olshtain (Reference Blum-Kulka and Olshtain1984) proposed four request perspectives:

-

a) Hearer-oriented which emphasizes the role of the hearer eg: Can you empty the bin?

-

b) Speaker-oriented which emphasizes the role of the speaker eg: Can I empty the bin?

-

c) Speaker and Hearer-oriented which stresses that of the hearer and the speaker eg: Can we empty the bin?

-

d) Impersonal which involves the use of neutral agents or passivation. Thus not referring to a particular person eg: Can the bin be emptied?

The difference between can I empty the bin and can you empty the bin is the fact that “can I…” stresses the role of the speaker in the speech event where as “can you…” stresses that of the speaker. Due to the fact that in requests, the hearer is the one under threat, any avoidance in naming the addressee as the principal performer of the act serves to soften the impact of the imposition.

Even though requests are quite prevalent in the day to day activities of language learners (be it asking for directions, asking for notes from a friend etc.) requests are believed to present inherent difficulties for language learners, who need to know how to perform requests successfully and to avoid the effect of being perceived as rude, offensive or demanding (Usó-Juan, Reference Usó-Juan, Martínez-Flor and Usó-Juan2010: 237). Requests require some degree of linguistic tact that often varies across languages, thus the transfer of strategies from one language to another may result in inappropriate or non conventional speech.

Studies have shown differences with respect to the amount and type of modification employed by native and non-native speakers as well as variation depending on the situational factors involved (Blum-Kulka and Olshtain, Reference Blum-Kulka and Olshtain1984; House and Kasper, Reference House and Kasper1987; Trosborg, Reference Trosborg1995; Hill, Reference Hill1997; Achiba, Reference Achiba2003; Schauer, Reference Schauer2009). These studies show that use of request strategies and perspectives is dependent on the type of interactional situation the locutor is faced with. Non-native learners are sometimes not fully aware of the power dynamics in interactions as shown in Hatam and Mohammad’s (Reference Hatam and Mohammad2014) study of Iranian L2 English learners who used mostly the impersonal perspective when addressing an interlocutor of a higher social status and the hearer-oriented perspective when addressing an interlocutor of a lower of equal social status.

Study abroad has long been seen as the sine que non of the acquisition of socio-pragmatic competence. We present next the studies on the effect of study abroad on the use of requests and request perspectives.

2.2. Effect of stay abroad on the use of request and request perspectives

Studies on study abroad show that after study abroad, learners tend to use new variants that were not acquired in the classroom. The use of informal variants like the use of on (we) instead of nous (we) and the deletion of the particle ne in the formulation ne… pas are usually observed in the discourse of learners who have spent some time in the native speech community. Studies on request (Hill, Reference Hill1997; Rose, Reference Rose2000; Barron, Reference Barron2003; Schauer, Reference Schauer2009; Achiba, 2013) also attest to the impact that study abroad has on the formulation of requests. Barron’s (Reference Barron2003) study of Irish L2 German learners who studied for one year in Germany shows an increase in the use of lexical/phrasal modifiers during their sojourn. Schauer (Reference Schauer2009) also with British L2 German learners found that after a year’s stay in Germany, the learners did not use the type of direct strategies (imperatives and unhedged performatives) that they had employed before the stay. The only study to the best of our knowledge on the effect of study abroad on the use of request perspectives is Shively’s (Reference Shively2011) study of the L2 pragmatic development of request of seven L2 Spanish learners from the United States on a semester abroad in Toledo, Spain during service encounters. Using naturalistic audio recordings that participants made of themselves while visiting local shops, banks, and other establishments, Shively observed that students’ requesting behavior changed over time from the overwhelming predominance of speaker-oriented forms to the greater use of hearer-oriented and elliptical requests. Thus from formulations like “I want coffee” to “Can you give me coffee” and “A coffee please”. The results bring to light a shift from the use of one request perspective to another after the stay in Toledo.

The studies cited above points to the fact that in general, in the development of requests, L2 learners over time and with a stay abroad move from the use of direct formulas to indirect ones. (Kasper and Rose, Reference Kasper and Rose2002; Barron, Reference Barron2003). In the model of request development proposed by Kasper and Rose (Reference Kasper and Rose2002), learners at the lowest stages of L2 proficiency use direct, unmitigated requests just like a speaker-oriented perspective and only at more advanced stages do they shift to more indirect forms and increasingly mitigated and syntactically complex utterances like hearer-oriented, impersonal or inclusive perspective.

We observe that studies focusing on request perspectives are scant. This paper contributes by using oral data from an open role play test to analyze the use of request perspectives by L1 and L2 French speakers.

3. RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESIS

The overall aim of the study is to investigate the choice of request perspectives by L1 French speakers in formal and informal situations and L2 French learner’s choice of request perspectives before and after stay in France and in Benin by means of an open role play test.

Based on results from previous studies within cross-cultural pragmatics we formulate the following research questions and hypothesis.

-

1. Does the choice of request perspective for L1 French and L2 French learners depend on the social distance and relationship of the interlocutors?

-

Since the degree of social distance and power relationship between interlocutors are very important factors in making a request (Blum-Kulka, Reference Blum-Kulka and Olshtain1984), we assume that the choice of request perspectives for L1 French speakers used in addressing friends (informal) would be different from that used for strangers (formal). We assume that since L2 French learners in the classroom are likely to have very little pragmatic knowledge, there will be no difference in the use of request perspectives in formal and informal situations before study abroad.

-

2. After study abroad, do the L2 French learners become more target like in their choice of request perspectives in formal and informal situations?

Research on L2 pragmatic development in the study abroad context reveals that learners generally adopt the pragmatic norms of the host country over the course of their sojourn abroad, often becoming more target-like pragmatically after four to nine months in the host country (Barron, Reference Barron2003; Brasdefer, Reference Brasdefer2007; Cohen and Shively, Reference Cohen and Shively2007; Schauer, Reference Schauer2009). This, they explain, is mainly due to the increased interaction with natives of the target language. Barron (Reference Barron2003) however believes that learners may not acquire target like sociolinguistic and socio-pragmatic patterns even after spending a full year abroad. We hypothesize that after study abroad, the L2 French learners will show differences in their choice of request perspectives in formal and informal situations and that due to a possible increase in interaction in French during the study abroad, the learners will adopt native speaker norms in their use of the request perspectives.

3.1. Methodology

The study is a longitudinal one involving 24 Ghanaian L2 French learners and a control group of 12 L1 French speakers from France (NF) and 12 L1 French speakers from Benin (NB). The Ghanaian participants are multilingual speakers having acquired a variety of languages in the family setting. Twi, Fante, Ga and Ewe are the frequent first languages spoken by the participants in our study. In addition to these languages, our participants speak English which is a language principally learnt and used at school and sometimes in families. All 24 learners had just completed three years of learning French as a foreign language as part of their Bachelor’s degree at a university in Ghana and were preparing to embark on a study abroad in France or in Benin. Their average age was 22.4 years and they had spent an average of six years learning French. At least 12 out of the 24 French L2 learners did a study abroad of 10 months in France and the other half did a study abroad of 10 months in Benin. We name the first group Group Nantes (GN) and the second group, Group Cotonou (GC)

3.1.1. The role play elicitation test

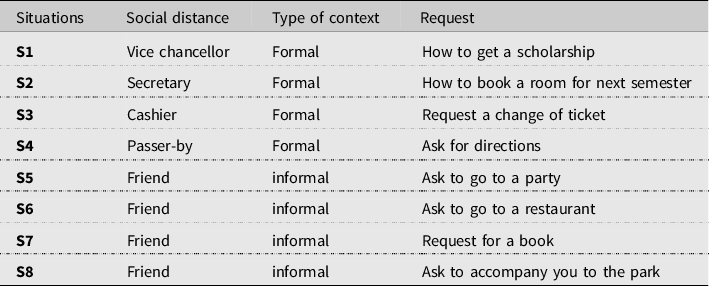

The corpus used in this study is made up of oral responses to a role play elicitation test consisting of eight situations. Four out of the eight situations required the learner to address to friend in various request situations. The second half required the learner to address to an unknown person or a known person of a higher social status in a variety of request situations. The detailed description of the situations was written in French on pieces of cards. The instructions for the task were given in English to ensure maximum comprehension of the procedure. The learner’s task was to pick the cards, read the situation and role play it in French. Due to the fact that the cards were shuffled each time, the order of responses to the task was different for each learner. The answers were recorded and orthographically transcribed with Exmaralda (Schmidt and Wörner, Reference Schmidt and Wörner2009).

3.1.2. Questionnaire

A shorter version of the Language Contact Profile (Freed, Dewey and Segalowitz, 2004) was used to examine how much the learners are exposed to French outside the classroom in Ghana and in their respective study abroad contexts (France and Benin). We maintained the background questions and reduced the questions on interaction and exposure to media. For the purpose of this study, we focused on one individual variable:

-

(1) Interaction in French

As mentioned in previous studies, interactions in the second language are opportunities to use the language and acquire native speaker norms. Learners were asked if they engaged in interaction in French and if so, at what rate per day based on a fixed scale: not at all (0), less than one hour per day (1), between one and three hours per day (2), between three and six hours per day (3), more than six hours per day (4).

3.2. Analysis

Our model of analysis is based on an adapted version of the coding manual for The Cross-Cultural Speech Act Realization Project (CCSARP), which Blum-Kulka and Olshtain (Reference Blum-Kulka and Olshtain1984) developed in their study of request perspectives. They proposed four request perspectives. The definitions proposed by Blum-Kulka and Olshtain (Reference Blum-Kulka and Olshtain1984) were adapted to fit our French data. Below are the four request perspectives with definition and examples from our data.

-

1. Speaker-oriented (S): Focuses on the speaker’s abilities, wants and desires.

Examples:

-

Je voulais savoir si j’pouvais l’changer. (NF, Hugo)

(I wanted to know if I could change it)

-

J’aimerais savoir le prix d’une chambre pour un semester. (NB, Pierre)

(I would like to know the price of a room for a semester)

-

2. Hearer-oriented (H): Focuses on the ability, wants and willingness of the hearer.

Examples:

-

Est-ce que vous pouvez échanger pour moi? (GN, Jen)

(Can you change it for me?)

-

Est-ce que tu es libre pour promener avec moi? (GN, Aba)

(Are you free to go for a walk with me?)

-

3. Impersonal (IMP): The speaker and hearer are detached from the utterance

Examples:

-

La faculté de droit est situé où? (GB, Abi)

(Where is the law faculty located)

-

Est-ce qu’il est possible à preter (GB, Adj)

(Is it possible to borrow it?)

-

4. Inclusive (INC): Focuses on both the speaker’s wishes and the hearer’s ability or role in the request.

Examples:

-

Est-ce qu’on peut se promener au jardin de plantes? (GN, Baa)

(Can we go for a walk at the park?)

-

Je souhaite que tu veux partir avec moi. (GN, Nii)

(I wish that you could go with me)

For each request, we observed whether the participant uses any of the above-mentioned types of request perspectives. Our dependent variable (request perspectives) has four different levels.

Methodological issues: Analysis was based on the head act. In cases where there was more than one request in the utterance, we analysed only the request that responds directly to the question asked.

Example: Je cherche la boulangerie, est-ce que vous pourriez me dire où je peux en trouver?

(I am looking for the bakery, could you tell me where I can find one?)

In such a case, we only analyse “could you tell me where I can find one” because it directly answers to question asked: ask for directions to the bakery. We consider I am looking for the bakery as a pre-request.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Use of request perspectives in French L1

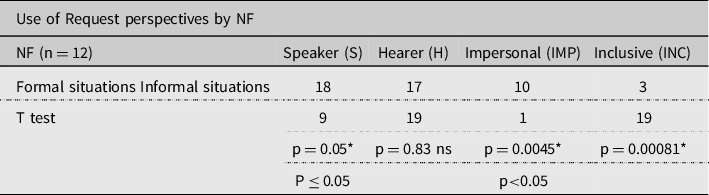

From the above table, we notice that the group of Native French (NF) show a difference in use for all four types of request perspectives in formal and informal situations. However the Student T test shows that even though the raw figures show some kind of difference in use, significant differences are only found in the use of the inclusive, the impersonal and the speaker-oriented perspectives. The NF employ a significantly higher use of the inclusive perspective in informal situations (mean = 1.5, sd = 1.08) than in formal situations (mean = 0.16, sd = 0.38). A contrastive tendency is observed in the use of the impersonal perspective. It’s use is significantly higher in formal situations (mean = 0.83 sd = 0.71) than in informal situations (mean 0.08, sd = 0.28). A close tendency is found in the use of the speaker-oriented perspective. There is a higher use in formal situations (mean = 1.5, sd = 0.93) than in informal situations (mean = 0.75, sd = 0.97). The Student T test found no significant difference in the use of the hearer-oriented perspective in formal and informal contexts.

Thus for the NF, the use of the inclusive, impersonal and speaker-oriented perspectives is dependent on the type of context, where as the use of the hearer-oriented is not dependent on the context.

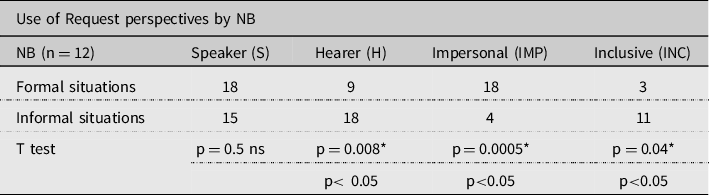

With the group of Native Beninese (NB), a significant difference in use of request perspectives in formal and informal situations is found in their use of the inclusive, the impersonal and the hearer perspectives. In the use of the inclusive perspective, the NB just like the NF employ a significantly higher inclusive perspective in informal situations (mean = 0.83, sd = 0.83) than in formal situations (mean = 0.25, sd = 0.45) and also, a higher use of the impersonal perspective in formal situations (mean 1.5, sd = 0.90) than in informal situations (mean 0.25, sd = 0.45).

In addition, they show a significant difference in the distribution of the hearer-oriented perspective in formal and informal situations. Their use the hearer-oriented perspective is slightly higher in informal situations (mean = 1.66, sd = 0.88) than in formal situations (mean = 0.75, sd = 0.62).

There is no significant difference in their use of the speaker-oriented perspective in the formal and informal contexts.

Thus for the NB, the use of the inclusive, impersonal and hearer-oriented perspectives is dependent on the type of context.

4.2. Use of request perspectives in L2 French

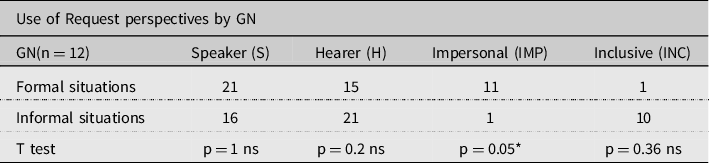

4.2.1. Use of request perspectives by learners in Group Nantes before study abroad

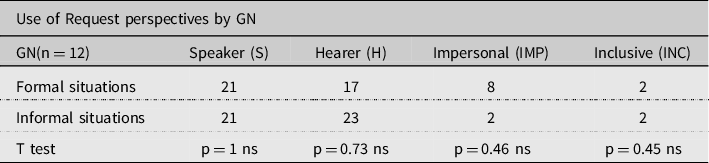

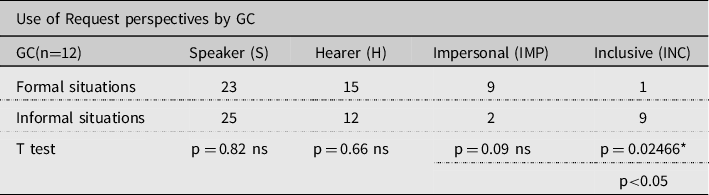

Before study abroad, we observe from the above table that Group Nantes (GN) shows no significant difference in their use of all the request perspectives in both formal and informal contexts. Thus, the GN’s use of the request perspective is not dependent on the type of context. It seems that the request perspectives are employed randomly and not based on the status of the person the learner is interacting with.

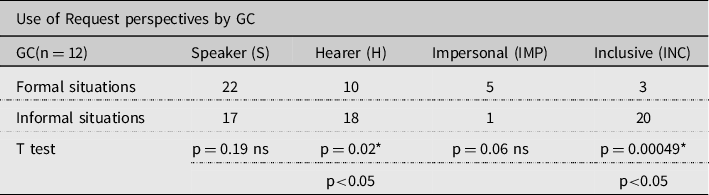

With the Group Cotonou (GC), the only significant difference is found in the use of the inclusive perspective. The use of the inclusive perspective in informal situations is slightly higher (mean = 0.75, sd = 0.86) than in formal situations (mean = 0.083, sd = 0.28).

Thus, the GC’s use of the inclusive perspective is dependent on the type of context. However, the use of the 3 other types of request perspectives is not dependent on the type of context.

4.2.2. Use of request perspectives by learners in Group Nantes after study abroad

After study abroad, Group Nantes shows no significant difference in their use of the types of request perspectives in formal and informal situations except for the use of the impersonal perspective. Just like their L1 counterparts from France, there is a significant high use of the impersonal perspective in formal situations (mean = 0.58, sd = 0.79) than in informal situations. (Mean = 0.08333 sd = 0.28). The use of the other three request perspectives is not dependent on the type of context.

4.2.3. Use of request perspectives by learners in Group Cotonou after study abroad

Group Cotonou also maintains a significant difference in the use of the inclusive perspective in formal and informal situations with a higher use in informal situations (mean = 1.667, sd = 0.98) than in formal situations (mean = 0.25, sd = 0.62) just like before study abroad.

In addition, just like their L1 counterparts from Benin, they show a significant difference in the use of hearer-oriented perspective. The use of the hearer-oriented perspective is slightly higher in informal situations (mean 1.5, sd = 0.67) than in formal situations (mean = 0.83, sd = 0.71). There is no significant difference in use of the speaker and impersonal perspectives in formal and informal contexts.

Thus, their use of the inclusive and hearer-oriented perspectives is dependent on the type of context whereas their use of the speaker-oriented and impersonal perspectives is not dependent on the type of context.

We observe that study abroad seems to have an effect on the use request perspectives for both group of learners and even more, both group of learners adopt a native-like pattern of use at the end of their stay in their respective contexts. The intensity and volume of interaction in the target language with natives of the target language outside of the classroom is believed to be the most important way to acquire target-like norms (Hill, Reference Hill1997; Pinto, Reference Pinto2005; Cohen and Shively, Reference Cohen and Shively2007; Schauer, Reference Schauer2009; Shively, Reference Shively2011).

In the use of request perspectives, a plausible assumption will be that the acquisition of native-like pattern of use is as a result of more interaction in French during study abroad. We present the results from a self-reported volume of interaction in French by both groups of L2 French learners.

4.3 L2 learner’s interaction in French

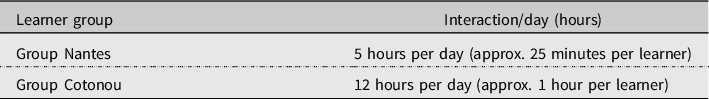

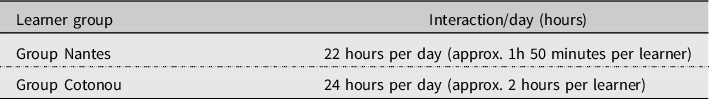

The mean volume of interaction for both groups of learners before and during study abroad is presented on the Tables 8 and 9.

Table 1. Description of the role play situations in terms of social distance

Table 2. Use of request perspectives by L1 French speakers from France (NF)

* Hypothesis confirmed at p ≤ 0.05 level ns = not significant

Table 3. Use of request perspectives by French L1 speakers from Benin (NB)

* Hypothesis confirmed at p ≤ 0.05 level ns = not significant

Table 4. Use of request perspectives by Group Nantes before SA

ns = not significant

Table 5. Use of request perspectives by Group Cotonou before SA

* Hypothesis confirmed at p ≤ 0.05 level ns = not significant

Table 6. Use of request perspectives by Group Nantes after SA

* Hypothesis confirmed at p ≤ 0.05 level ns = not significant

Table 7. Use of request perspectives by Group Cotonou after SA

* Hypothesis confirmed at p ≤ 0.05 level ns = not significant

Table 8. Interaction in French with L1 French speakers before study abroad

Table 9. Interaction in French with L1 French speakers during study abroad

This self reported interaction in French shows clearly that there was an increase in interaction in French during the study abroad (approximately 25 minutes per day versus 1h50 minutes per day for GN learners and approximately 1 hour versus 2 hours per day GC learners) We observe that there was relatively more interaction in French during the study abroad. Which is normal due to the fact that during study abroad learners get to interact with a wide range of people of the target language in diverse situations.

5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The study examines the use of the request perspectives in two distinct contexts: four situations addressing an unknown interlocutor or a known interlocutor of a higher social status that we term formal situations and four situations addressing friends that we term informal situations. Using a role play test, the study sought to find out whether the type of context (formal and informal) has an effect on the choice of request perspectives. The study looks at the choice of the request perspectives by L1 French speakers from France and Benin in formal and informal situations and also, choice by L2 French speakers before and after study abroad in formal and informal situations. The role of interaction with L1 French speakers during study abroad on the use of request perspectives is also looked into.

The results show that the two groups of L1 French speakers are quite similar in their use of inclusive and impersonal perspectives. Both group of L1 speakers show that the use of the inclusive and impersonal perspective is dependent on the type of interlocutor the speaker is faced with, used mostly when addressing a friend than addressing an unknown interlocutor.

The difference between the two groups is in their use of the speaker-oriented and hearer-oriented perspectives. Where as the status of the interlocutor has no effect on the use of the hearer-oriented perspective for the L1 speakers from France, the L1 speakers from Benin use of the hearer-oriented perspective is dependent on the context. The hearer-oriented perspective is mostly used in informal situations. Also, where as the status of the interlocutor has no effect on the use of the speaker-oriented perspective for the L1 speakers from Benin, the L1 speakers from France use it more when interacting with unknown interlocutors.

Our hypothesis that the two groups of L1 speakers would make use of different request perspectives in formal and informal situations is confirmed for the use of the speaker-oriented and hearer-oriented perspectives.

Before study abroad, results show that the use of request perspectives by the learners who stayed in Nantes (GN) is not dependent on whether the interlocutor is a friend or a stranger. For the leaners who stayed in Cotonou (GC), the same is observed in relation to the use of the speaker-oriented, hearer-oriented and impersonal perspectives only. However, for the use of the inclusive perspective, we observe that it is used mostly when addressing friends. Both group of learners had relatively low interaction in French with L1 French speakers before the stay in their respective contexts (approximately 25 minutes per day for the GN and 1 hour per day for the GC). Our hypothesis that before study abroad, the L2 learners won’t show any difference in use of the request perspectives in formal and informal situations is partially rejected. It is only true for GN.

After study abroad, we observe a change in GN’s use of the impersonal perspective. Their use of the impersonal perspective is mainly used when addressing an unknown person than when addressing a friend. This “new” use is very interesting because the same pattern is found with the L1 speakers from France. The use of the other three request perspectives just like before is not dependent on who the interlocutor is.

The GC on one hand maintains the same use before the study abroad, thus whereas their use of speaker-oriented and impersonal perspectives is not dependent on the type of context and use of inclusive perspective is dependent on the type of context. On the other hand, the GC adopts a “new” use, which is; their use of the hearer-oriented perspective is dependent on the formality of the context. The results show that the GC uses the hearer-oriented perspective mostly in informal situations than in formal situations. This new pattern is very interesting because the same pattern is observed with the L1 speakers from Benin and is actually the only aspect that differentiates their use from that of the L1 speakers from France.

Our assumption that there will be a change in use of the request perspectives after study abroad is confirmed.

During study abroad, there is an increase in interaction in French for both groups of learners (25 minutes per day to 1hour 50 minutes per day for GN and 1hour per day to 2 hours per day for GC). This seems to account for the use of native speaker patterns especially for the GN who showed no native pattern before study abroad. Our hypothesis that high volume of interaction during study abroad will account for native-like pattern of use is confirmed.

Through the intermediary of a role play test, we observe that study abroad seems to have an effect on the use of request perspectives. The L2 French learners showed minimal difference in use of request perspectives in formal and informal situations before study abroad. With the increase in interaction in French with L1 French speakers during study abroad, their use of request perspectives change, thereby adopting some native speaker patterns like the use of the impersonal perspective mostly in informal situations and the use of the hearer-oriented perspective mostly in formal situations.

Our study is consistent with Shively’s (Reference Shively2011) work on the use of request perspectives by L2 Spanish learners on study abroad that shows that at the end of the stay, some learners used the request perspectives differently that conformed to the use by L1 Spanish speakers.