Introduction

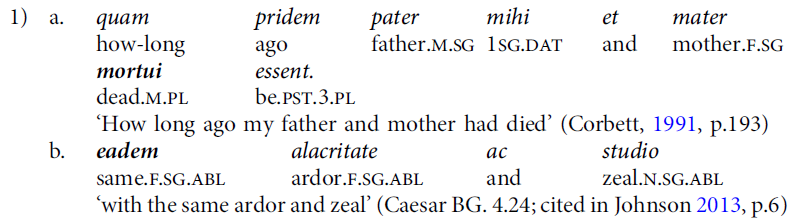

Agreement with coordination is a complex issue and different languages may use different strategies (cf. Sadler, Reference Sadler, Butt and King1999; Wechsler and Zlatić, Reference Wechsler and Zlatić2000; Kuhn et al., Reference Kuhn, Sadler, Butt, King, Butt and King2007; Borsley, Reference Borsley2009; Dalrymple and Hristov, Reference Dalrymple, Hristov, Butt and King2010). When the coordination includes conjuncts with conflicting features, languages may follow resolution rules (cf. Givón, Reference Givón1970; Dalrymple and Kaplan, Reference Dalrymple and Kaplan2000) or use closest conjunct agreement (cf. Corbett, Reference Corbett1991; Wechsler and Zlatić, Reference Wechsler and Zlatić2003). A single language, such as Latin, may use different strategies in case of coordination of nouns with different genders: masculine resolution (1-a) (for human nouns) or agreement with the closest conjunct (1-b).

Romance languages, such as Italian, Spanish and Portuguese, use the same masculine resolution strategy, but also allow for CCA. In example (2-a) (from Demonte and Perez-Jimenez, Reference Demonte and Perez-Jimenez2012), the determiner and prenominal adjective show CCA while the post-nominal adjective is not marked for gender. CCA is observed for the post-nominal adjective in example (2-b) (Villavicencio, Sadler and Arnold, Reference Villavicencio, Sadler, Arnold and Müller2005), and for the prenominal adjective in Italian (2-c) (Benincà, Reference Benincà, Salvi and Frison1988).Footnote 2

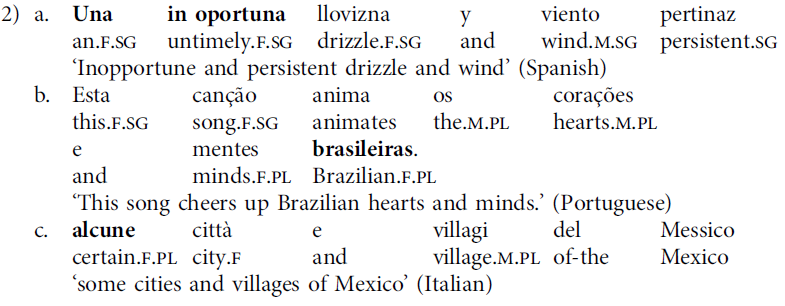

Feminine agreement with nouns of mixed genders is also attested in classical French (Viennot, Reference Viennot2014).

In (3a), the postnominal adjective nouvelle has wide scope over the two nouns, since ?Armez-vous d’un courage (‘arm yourself with a courage’) is weird without an adjective: un (‘a’) refers to a subtype of courage and de would be used without an adjective: Armez-vous de courage (‘arm yourself with courage’).

The masculine resolution rule in contemporary French

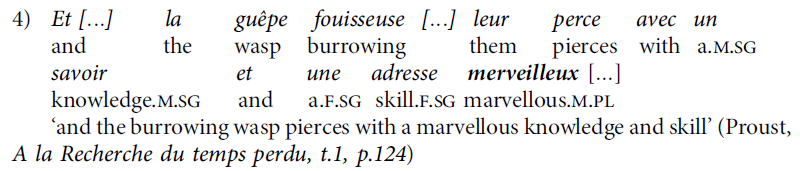

According to some authors (cf. Viennot, Reference Viennot2014), contemporary French has lost the possibility of CCA due to the power of the (masculine) prescriptive norm. Other authors suggest a more nuanced view: Grevisse and Goosse (Reference Grevisse and Goosse2016, p.338) write: “si les noms sont de genre différents, l’épithète se met au genre indifférencié, c’est-à-dire masculin”.Footnote 3

But they add: “La règle générale n’est pas toujours respectée […]. La tradition grammaticale, qui correspond à un certain sentiment des usagers, estime choquant pour l’oreille que le nom féminin soit dans le voisinage immédiat de l’adjectif.” (5) (Grevisse and Goosse, Reference Grevisse and Goosse2016, p. 339)Footnote 4 and conclude: “il est préférable chaque fois que cela est possible d’accorder avec l’ensemble des noms”.Footnote 5

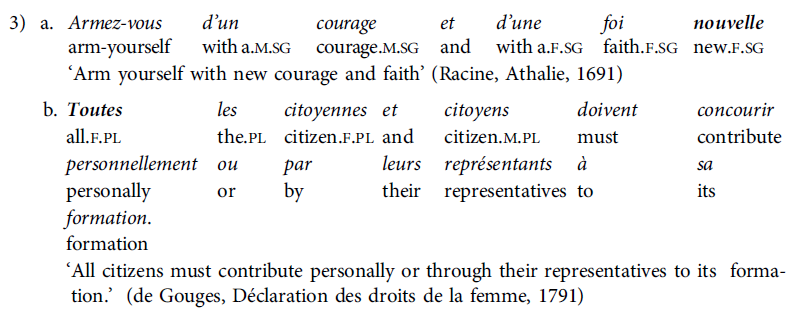

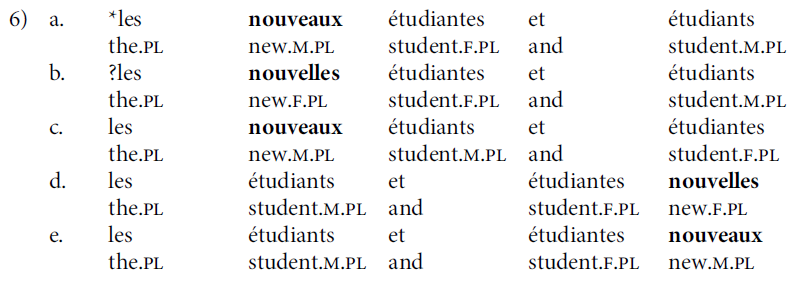

According to Curat (Reference Curat1999), examples (6-a), (6-c) and (6-e) obey the resolution rule but (6-a) is not acceptable. In (6-b), CCA is claimed to be dubious because it is not compatible with the resolution rule. In post-nominal position, Curat (Reference Curat1999) claims that the feminine adjective only modifies N2 (6-d), whereas the masculine adjective may modify the coordination as a whole (6-e).

Thus, the status of the masculine resolution rule is unclear in French, especially for prenominal attributive adjectives when the closest noun is feminine (5) (6-a). Furthermore, most authors rely on their own intuition or a handful of attested examples.

The aim of this article is to pursue a quantitative and empirical study of gender agreement of French attributive adjectives in case of coordination of nouns with different genders. We provide new contemporary data on gender agreement of plural adjectives with plural nouns, which shed some light on the acceptability of CCA, and on the factors that may favour it over resolution.

CCA and Corbett’s agreement hierarchy

Putting French in a more general perspective, we take into account Corbett’s typological work. Looking at a wide variety of languages, Corbett considers that agreement is an asymmetric relation between a controller and a target, involving syntactic, semantic and pragmatic factors. In his view, CCA is not a ‘repair’ mechanism yielding acceptable but otherwise ungrammatical output (Peterson, Reference Peterson1986; Bhatt and Walkow, Reference Bhatt and Walkow2013), but a strategy available in many language families, such as Slavic or Bantu languages. He proposes that three factors may favour CCA for languages with different agreement strategies (see Corbett, Reference Corbett1983, Reference Corbett1991, Reference Corbett2006):

-

Controllers referring to inanimates

-

Targets before Controllers (postverbal subject vs. preverbal subject)

-

Agreement hierarchy

attributive < predicate < relative pronoun < personal pronoun

← non-resolution ————————————resolution →

In his view, animate nouns may favour a more semantic agreement, for example plural agreement with two singular conjuncts, hence resolution. The interaction between CCA and directionality is compatible with a structural explanation (when the subject is postverbal, the closest noun is the highest noun, see below Section 4.2). It is compatible as well with an incremental processing account: only in backward agreement, when the target follows the controller, does the speaker know the features of all conjuncts before computing target agreement.

The agreement hierarchy may also be explained in terms of linear and structural distance. An attributive adjective (6-c) (6-b) is closer to the (controller) noun (and belongs to the same noun phrase) than a predicative one, which belongs to the verbal phrase and may be separated from the (controller) noun by a copula (5) (7), hence a penalty for CCA for predicative adjectives.

If these factors apply to French gender agreement, CCA should be more frequent for prenominal adjectives than for post-nominal adjectives. We also expect differences between human and non-human nouns, if human nouns favour resolution in general.

The article is organized as follows: Section 1 briefly reviews previous literature about adjective agreement and positions in French. The new empirical data are presented in Section 2 (a corpus study) and Section 3 (an acceptability experiment). We analyse the results, discuss the factors that interact with CCA, and compare gender and number agreement in Section 4.

1. Gender agreement of French attributive adjectives

1.1 French nouns and gender

Like most other Romance languages, French has two grammatical genders, feminine (fem) and masculine (masc). For non-human nouns, grammatical gender is usually considered arbitrary. For example, the noun chaise ‘chair’ (la chaise) has feminine gender, while the noun livre ‘book’ (le livre), on the other hand, has masculine gender.

As in many languages, grammatical gender is usually associated with social gender for human nouns: masculine nouns tend to refer to males and feminine nouns to females. For example, garçon (‘boy’) is masculine and fille (‘girl’) is feminine, even if many personal nouns have a common gender, such as journaliste, ‘journalist.m/f’.Footnote 6 For human nouns presenting gender alternation (chanteur/chanteuse ‘singer.m/singer.f’), we leave open the debate whether they are formed by parallel suffixation, by derivation of one noun from the other, or by inflection from a common lexeme (Spencer, Reference Spencer2002; Bonami and Boyé, Reference Bonami, Boyé, Baerman, Bond and Hippisley2019).

1.2 French adjectives and gender

The paradigm of French adjectives has been discussed in morphology (cf. Morin, Reference Morin and Clas1992; Bonami and Boyé, Reference Bonami and Boyé2005).Footnote 7 In Lexique (New et al., Reference New, Pallier, Ferrand and Matos2001), 82% adjectives are marked for gender (masc/fem) in written French (as petit ‘small’, joli ‘pretty’ in Table 1), and others are syncretic (as jeune ’young’), while in spoken French, 66% adjectives have syncretic forms (masc/fem), as is the case for joli.

Table 1. Inflection of French adjectives

In what follows, we use a written corpus with various adjectives, but in our experiment we only use adjectives with an audible gender marking (petit/e) (Section 3).

1.3 Agreement strategies for French attributive adjectives

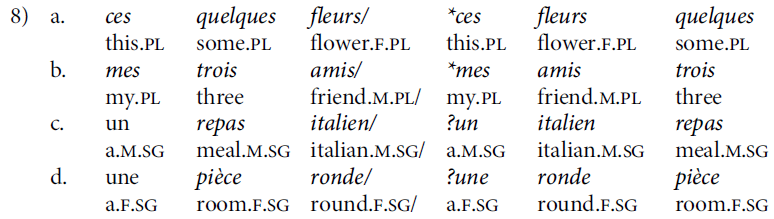

Attributive adjectives in French can be in pre- or post-nominal position, depending on their semantic class (cf. Wilmet, Reference Wilmet1981; Bouchard, Reference Bouchard1998; Miller, Pullum and Zwicky, Reference Miller, Pullum and Zwicky1997). For example, indefinites and cardinals are only found in prenominal position (8-a)-(8-b), while size, color or relational ones occur post-nominally (8-c)(8-d).Footnote 8

Many evaluative adjectives like agréable ‘pleasant’ (9) can alternate between pre- and post-nominal positions with roughly the same meaning (Abeillé and Godard, Reference Abeillé and Godard1999; Thuilier, Fox and Crabbé, Reference Thuilier, Fox and Crabbé2012; Laenzlinger, Reference Laenzlinger2005).

Following many French grammar books (cf. Riegel, Pellat and Rioul, Reference Riegel, Pellat and Rioul2018), French would be unique among Romance languages in only allowing resolution in case of conflicting genders: the coordination of a masculine and a feminine noun is supposed to be resolved to masculine, regardless of whether the nouns are animate (10) or not (4).

Masculine agreement is sometimes considered as default agreement (Grevisse and Goosse, Reference Grevisse and Goosse2016), since it is used for expressions without grammatical gender: it is the gender used with sentential or verbal subjects (11-a) and with the expletive pronoun (11-b).

The difference between default agreement and resolution rules has been debated (cf. Nevins and Weisser, Reference Nevins and Weisser2019), since in languages with three genders, default agreement is usually neuter while resolution is usually masculine. We use the term resolution rule in this article referring to masculine agreement when there is a conflict of features.Footnote 9

In Section 2 and Section 3, we use coordination with one determiner shared by two plural nouns D A N1 et N2 or D N1 et N2 A . We choose plural nouns so that there is no interaction with number agreement (see An and Abeillé (Reference An and Abeillé2017, Reference An and Abeillé2019) for a discussion of CCA for number agreement with French determiners and adjectives). It is assumed that with a shared determiner, the two conjuncts are semantically related and form a conceptual unit (Wälchli, Reference Wälchli2005; Le Bruyn and de Swart, Reference Le Bruyn and de Swart2014). The adjective thus tends to be interpreted as having scope over the coordinated nouns. We do not discuss adjectival scope much further, but only include examples where the adjective makes sense with scope over the whole coordination in the following sections. Our empirical data come from a corpus study on the one hand, and an acceptability rating experiment on the other hand.

2. New corpus data

2.1 Attributive Adjective agreement in FrWac

We chose FrWac (French Web as a Corpus, Baroni et al., Reference Baroni, Bernardini, Ferraresi and Zanchetta2009) because it is a large (1.6 billion word) corpus of contemporary French, including informal uses, annotated for parts of speech. In this corpus, we found 32,769 tokens for D A N1 et N2 and 59,818 tokens for D N1 et N2 A . We randomly took 2,500 items for each structure and annotated automatically the gender information of nouns and adjectives with the Lexique database (New et al., Reference New, Pallier, Ferrand and Matos2001). We only selected plural nouns (among the two sets of 2500, it turns out that 1081 were plural for prenominal A and 1,000 were plural for post-nominal A). Restricting our data to nouns with different genders, we checked each item manually and removed the examples where the A N combination is a compound (12-a)Footnote 10 and when the A has scope on only one conjunct or has a syncretic form (12-b).

We thus obtained 290 D A N1 et N2 and 370 D N1 et N2 A sequences. Table 2 reports the occurrences of masc/fem adjectives with the two plural nouns of different genders.

Table 2. Adjective agreement with mixed-gender coordinate plural nouns in FrWac

In both prenominal and post-nominal positions, when the closest noun is masculine, masculine agreement may be triggered by resolution or by CCA. The adjectives are always masculine in these cases (13-a), (13-b).

In combinations like D A N1 f etN2 m and D N1 m et N2 f A , we found two possibilities for A agreement: the resolution rule (14-a), (14-b) or CCA (14-c), (14-d). However, with a closest feminine noun, resolution is very rare for prenominal A (5%), while it is at 55% for postnominal A.

2.2 Is masculine resolution the only agreement rule?

Table 2 shows that CCA exists in French and is not necessarily the same as resolution. It also shows a strong preference for CCA in prenominal position compared to post-nominal position (p < .001, Fisher’s Exact Test). This may be explained by structural proximity: in cases of D A f N1 f et N2 m , the feminine closest conjunct is also the highest one (see Section 4.2 below).

Following previous literature (see Willer-Gold et al., Reference Willer-Gold, Arsenijević, Batinić, Becker, Čordalija, Kresić, Leko, Marušič, Milićev and Milićević2017), we consider three possible strategies: closest conjunct agreement (CCA), (masculine) resolution, and first conjunct agreement (FCA). For example in Slovenian, on top of masculine resolution agreement, agreement is possible with the closest noun (neuter here) or with the first noun (feminine here):

In a two gender system like French, FCA may predict the same agreement strategy as CCA, with a prenominal A f N1 f et N2 m , but not with a postnominal N1 f et N2 m A f , where CCA predicts A m .

Table 3 lists all potential cases of mismatch, with the three corresponding strategies.Footnote 12 In cases like A m N1 m et N2 f , FCA, CCA and resolution converge: masculine agreement is preferred over feminine. In the two cases A f N1 f et N2 m and N1 m et N2 f A f , CCA and resolution diverge. In the first case, CCA is preferred and also coincides with FCA since the trigger is the first conjunct. In the second case, (feminine) CCA does not coincide with FCA and it seems as acceptable as (masculine) resolution.

Table 3. Adjective gender agreement in FrWac and the three agreement strategies

We can see that FCA is not an independent strategy in French, since N f et N m A f is not allowed (16). FCA is never observed outside CCA ( A f N f et N m ) or resolution (N m et N f A m ).

On the other hand, CCA is an independent strategy since it is observed outside resolution ( A f N f et N m ) or FCA (N m et N f A f ) : in cases of N1 m et N2 f A f , CCA is the only factor that plays a role, as the feminine closest noun is the lowest one. We also discover that CCA has more weight than resolution since the preference for feminine in A N f et N m is greater than the preference for masculine in N m et N f A .

Overall, we have more examples compatible with CCA (576: 87%) than examples compatible with resolution (507: 76%). Looking at prenominal adjectives, we have 285 examples compatible with CCA (98%), and 202 compatible with resolution (69%). Leaving aside FCA, we have 88 examples of ‘CCA only’ (30%) and only 5 of ‘resolution only’ (1,7%). Looking now at postnominal adjectives, we found 291 examples compatible with CCA (78%) and 305 compatible with resolution (82%). Leaving aside FCA, we have 65 examples of ‘CCA only’ (17%), and 79 examples of ‘resolution only’ (21%). Given the overwhelming weight of CCA for prenominal A, we conclude that A m N m et N f may be considered as a case of (masculine) CCA.

In order to test the acceptability of such corpus data, we ran an acceptability rating experiment to see whether the corpus frequencies correspond to speaker’s preferences. We also want to compare CCA and attraction errors (Bock and Miller, Reference Bock and Miller1991), and to test the differences between human and non-human nouns, since grammatical gender has a social meaning for human nouns (Corbett, Reference Corbett1991).Footnote 13

3. Experimental data

Since formally collected judgements are more reliable than speakers’ intuitions (cf. Wasow and Arnold, Reference Wasow and Arnold2005; Gibson and Fedorenko, Reference Gibson and Fedorenko2010; Sprouse, Schütze and Almeida, Reference Sprouse, Schütze and Almeida2013), and more formal methods may reveal previously unobserved patterns in the data (cf. Keller, Reference Keller2000; Abeillé and Winckel, Reference Abeillé and Winckel2020), we ran an acceptability judgement task. Most experimental studies deal with (number) subject-verb agreement (cf. Keung and Staub, Reference Keung and Staub2018; Foppolo and Staub, Reference Foppolo and Staub2020), while some deal with gender subject predicate agreement (Willer-Gold et al., Reference Willer-Gold, Arsenijević, Batinić, Becker, Čordalija, Kresić, Leko, Marušič, Milićev and Milićević2017). As far as we know, this is the first experimental study of CCA in the nominal domain. We use a factorial design which treats adjective gender, humanness, and adjective position as three factors, each with two values (Am/Af, human/non-human and pre/post).Footnote 14

As in our corpus study, we only use plural nouns, in order to avoid an interaction with number agreement. We also chose a gender neutral plural form for the determiner (de/des ‘ind.pl’). We use 12 control items with attraction errors to compare their acceptability with that of CCA.

3.1 Materials

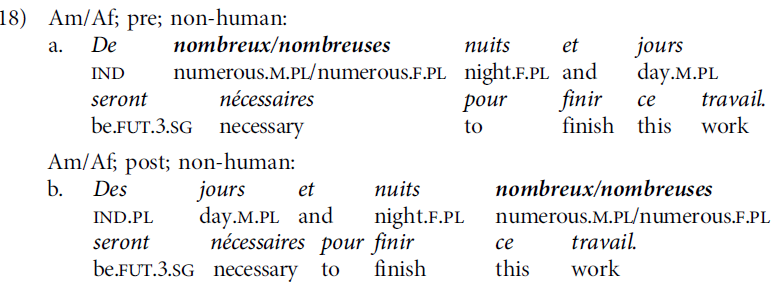

We built 24 experimental items, 12 with human (17) plural binomials and 12 with non-human (18).Footnote 15 The adjectives can appear in both pre- and post-nominal positions and they can have scope over the coordination in both positions. We chose human nouns with distinct masculine and feminine forms, in order to avoid interference from implicit expectations about social gender bias.

For each item, there are four conditions: masculine (Am) and feminine (Af) adjectives in prenominal (pre) position (17-a), (18-a), as well as in post-nominal (post) position (17-b), (18-b). We changed the order of binomials in (17-a) and (17-b) so that the closest conjunct is always feminine in order to distinguish CCA from resolution. Thus, Am corresponds to resolution agreement and Af to CCA.

With prenominal adjectives, the determiner is de (and not des) in order to force the adjective to have wide scope over the coordination - plural de is a variant of indefinite des only with a prenominal adjective (des/*de garçons vs des/de grands garçons) (Milner, Reference Milner1978). With postnominal adjectives, the more natural reading is wide scope too since the determiner is shared between the two nouns.

We also included 12 control items, in two versions, one grammatical (19-a) and one with an agreement error (19-b), in order to test the differences between CCA and attraction errors (cf. Fayol, Largy and Lemaire, Reference Fayol, Largy and Lemaire1994; Keung and Staub, Reference Keung and Staub2018). The ungrammatical version included a closest feminine noun complement.

3.2 Procedures

These materials were included in an acceptability judgement paradigm on the Ibex on-line platform (Drummond, Reference Drummond2013). After providing informed consent, participants read each sentence on a computer screen and judged its acceptability on a range from 0 (not at all acceptable) to 10 (completely acceptable), which is the usual scale in the French school system.Footnote 16 After rating each sentence, participants had to answer a simple comprehension question, to ensure that they were attentive.

Participants could only see one version for each item, the distribution of which was counterbalanced across participants. The order of experimental items was also randomized in each trial. In addition there were 20 filler items with four conditions for each item from an unrelated experiment. Experimental items, controls and fillers were distributed across three lists using a Latin square design so that each list contained 24 experimental sentences, 12 controls, 20 fillers (from an unrelated experiment) and 3 practice items.

The duration of the experiment was estimated at 10 minutes on average. 43 native speakers of French (21 to 82 years old, median = 34, 26 female, 10 male, 3 did not report their gender), recruited on the RISC website (http://www.risc.cnrs.fr/) volunteered to participate in the experiment. Three participants were removed because their accuracy for comprehension questions was less than 75% and one was removed because they rated the ungrammatical controls higher than the grammatical controls.

3.3 Results

The results are shown in Figure 1 and Appendix B. Error bars in all figures in this article correspond to 95% confidence intervals. In general, the experimental items were rated higher than the ungrammatical controls (with attraction errors) (mean = 2.73), but lower than the (very simple) grammatical controls (mean = 9.52). Feminine adjectives (mean = 6.73 in prenominal position, mean = 6.37 in post-nominal position) were also preferred over masculine adjectives (mean = 5.03 in prenominal position, mean = 5.89 in post-nominal position), and this preference was stronger in prenominal position. We did not find effects of gender or age of participants.

Figure 1. Results of the adjective gender agreement rating experiment.

3.3.1 Effects of Directionality

We analysed the data with a mixed-effects ordinal regression model using the clmm() function in the ordinal package (Christensen, Reference Christensen2018). This is an appropriate statistical model for ratings that cannot be assumed to represent an interval scale, i.e., the values may not represent equally spaced points in subjects’ subjective acceptability space. Fixed effects in this model were position (pre vs. post) and gender (Am/Af). We also included maximal random effects (random intercepts and random slopes) for items and subjects. The coefficient of random and fixed effects is presented in Appendix C1 (Table 4).

There were no significant main effects of gender and position. But the interaction between gender and position was significant (p = 0.006). CCA was particularly preferred in prenominal position, which is consistent with our corpus data (Section 2) and with Corbett (Reference Corbett1991)’s typological observation that CCA is more acceptable when the target precedes the controller (cf. Introduction).

3.3.2 Effects of Humanness

In the A-N1f-et-N2m condition, we ran a similar mixed-effect ordinal regression model as in the previous section, with gender, humanness and their interaction as fixed effects and random slopes for subjects and gender as random slopes for items. The results (see Appendix C2 Table 5 for more details) showed a significant effect of A gender (p = 0.01). As shown in Figure 2, in prenominal position, feminine adjectives were preferred with both human nouns and non-human nouns. The difference between Am/Af with non-human nouns was bigger than with human nouns, but the interaction between humanness and A gender was not significant (p = 0.24).

Figure 2. Humanness and adjective gender agreement in the rating experiment.

However, in post-nominal position, masculine adjectives were preferred with human nouns, while feminine adjectives were preferred with non-human nouns. This interaction was significant (p = 0.004) in the mixed-effect ordinal regression model. We did not find significant main effects for A gender (p = 0.59). Across humanness conditions, masculine and feminine adjectives were equally acceptable. The main effect of Humanness is marginal (p = 0.07).

To sum up, (feminine) CCA was preferred with prenominal adjectives compared to post-nominal adjectives. This is consistent with our corpus data, but quite striking given the weight of the masculine resolution rule which is taught as the prescriptive norm in France. If we zoom in on the data, the interaction between gender agreement and humanness was significant only in post-nominal position. Masculine (resolution) agreement was more acceptable with human nouns, while feminine agreement (CCA) with non-human nouns (compared with human nouns).

4. Discussion

4.1 Closest conjunct agreement is not an attraction error

Our experiment has shown quite sharp differences between closest conjunct agreement in conjoined NPs and attraction errors. CCA is in fact preferred over resolution for gender adjective-noun agreement, except for human nouns with post-nominal adjectives. On the other hand, sentences with attraction errors are judged almost three times lower than closest conjunct agreement.

Proximity plays a role in language processing in general (Bock and Miller, Reference Bock and Miller1991; Deevy, Reference Deevy1999), but its effects in CCA are different from attraction errors (Keung and Staub, Reference Keung and Staub2018), so these two phenomena should be distinguished. In examples with attraction errors, N1 is the syntactic head (see Figure 4 next section) and it contributes its gender and number features to the NP subject, whereas coordination is a specific syntactic structure with specific properties, which we will discuss in the following section.

4.2 CCA and the syntactic Structure of Coordination

From the theoretical point of view, CCA is puzzling since agreement usually obeys locality constraints (between a head and its subject, specifier or local modifier, or between a trigger and the highest c-commanded probe cf. Chomsky, Reference Chomsky and Kenstowicz2001). Some authors have tried to reduce CCA to standard agreement with clausal coordination and ellipsis (Aoun, Benmamoun and Sportiche, Reference Aoun, Benmamoun and Sportiche1994, but see Munn, Reference Munn1999). Most authors consider that it is related to the exceptional syntax of coordination, which does not have the syntactic features of a standard controller. Either the conjunction is a syntactic head (Kayne, Reference Kayne1994), but without gender features, or the coordination is unheaded (Ross, Reference Ross1967; Borsley, Reference Borsley2005).

Looking more closely at the syntax, two asymmetric syntactic structures have been proposed for coordination in the literature (Figure 3). Even though they differ from each other as to whether the conjunction is the head (Structure (a)) or the structure is non headed (Structure (b)), they both consider that the first conjunct is in a structurally higher position than the second conjunct.

Figure 3. Two syntactic structures for a coordination phrase.

Figure 4. Syntactic structure for an NP with a complement.

As shown in Figure 3a, in minimalist approaches, the conjunction is the head, the first conjunct occupies the specifier position and the second the complement position. If the conjunction (and) is the head, it may have its own number value (plural) but it does not have a gender value (Bhatt and Walkow, Reference Bhatt and Walkow2013). Assuming agreement can be triggered by the specifier, only the gender of the first conjunct is accessible for agreement.Footnote 17 This predicts first conjunct agreement but not CCA with the second conjunct.

In unification-based grammars, there is no Agree operation but feature matching through unification. Certain features, in particular person and gender, are not distributive (Dalrymple and Kaplan, Reference Dalrymple and Kaplan2000; Sag, Reference Sag2005): they are not necessarily shared by the conjuncts and their value for the coordination as a whole is computed by special feature resolution rules and not by unification.Footnote 18 In HPSG, a hierarchical structure is assumed for coordination (Borsley, Reference Borsley2005, see Figure 3b), but it is non headed, and the conjunction is only the head of the conjunct it combines with. Since there is no head to assign morphosyntactic features, such as gender, number, person, several options are available for the coordination as a whole.Footnote 19 Villavicencio, Sadler and Arnold (Reference Villavicencio, Sadler, Arnold and Müller2005) analyse gender and number agreement of attributive adjectives in Portuguese. In their analysis, agreement is always with the whole coordination phrase, which has three agreement features: concord (for resolution), left-agr (with concord features from the left-most conjunct) and right-agr (with concord features from the right-most conjunct). This analysis may well account for our French data, although not taking preferences into account.

4.3 Linear Distance vs Structural Distance

Comparing prenominal and post-nominal adjectives, if CCA is superficial and only sensitive to linear proximity (number of intervening words), the preference for CCA should be the same in the two positions. On the other hand, if we look at structural distance (number of intervening nodes), prenominal and post-nominal adjective agreement should be different. In case of CCA, the prenominal adjective agrees with the highest conjunct (highest conjunct agreement or HCA, cf. Aoun, Benmamoun and Sportiche, Reference Aoun, Benmamoun and Sportiche1994; Munn, Reference Munn1999), while the post-nominal adjective agrees with the lowest conjunct. Thus, CCA should be preferred in prenominal position since the structural distance (the number of syntactic nodes between the adjective and the controller noun) is shorter with the first conjunct (see discussion of Willer-Gold et al., Reference Willer-Gold, Arsenijević, Batinić, Becker, Čordalija, Kresić, Leko, Marušič, Milićev and Milićević2017 for South Slavic languages), while linear distance (the number of words between the adjective and the closest noun) does not change between prenominal and post-nominal positions.

Both our experimental and corpus data show an effect of the syntactic position when the adjective agrees in gender with a coordinated NP. The preference for CCA is stronger in prenominal position than in post-nominal position for both human nouns and non-human nouns. This result can be explained by taking structural proximity into account: assuming a hierarchical structure for coordination (Figure 3), the closest conjunct is the highest one (and is structurally closest to the target counting the number of intervening nodes) with prenominal adjectives. Both linear and structure distance may also explain the difference between attributive and predicative agreement, since predicative agreement favours Resolution: the attributive adjective is closer to the (closest) noun than the predicative one which is separated from the subject by the copular verb (5) (7). In terms of structural distance, the attributive adjective belongs to the same noun phrase as the (controller) noun, while the predicative adjective belongs to the verbal phrase and is thus separated from the (controller) noun by an extra phrasal boundary.

This asymmetry is also consistent with the agreement hierarchy proposed by Corbett (Reference Corbett1991) — that is to say that CCA is preferred when the target precedes the controller (Introduction). This effect of directionality can also be explained in terms of processing difficulties (see Haskell and MacDonald, Reference Haskell and MacDonald2005 and Hemforth and Konieczny, Reference Hemforth and Konieczny2004 for psycholinguistic evidence). Human language processing is incremental in nature (cf. Tanenhaus et al., Reference Tanenhaus, Spivey-Knowlton, Eberhard and Sedivy1995; Kaiser and Trueswell, Reference Kaiser and Trueswell2004; Levy, Reference Levy2008): we do not wait until we have heard an entire sentence to start disambiguating and understanding. In N-A order, the speaker can anticipate agreement with the whole coordination phrase. However, in A-N order, the speaker cannot anticipate the coordination and could agree with the first noun in a strategy that we may call ‘early’ agreement.

But neither linear nor structural proximity is the only factor. One must take into account the syntactic function of the items. In CCA, the second noun is the lowest one but can nevertheless trigger agreement. In attraction errors, the complement is in the same structural position but it does not trigger agreement (Figure 4). The key difference is that with coordination, neither of the two nouns is the head (Figure 3), while in attraction errors, N1 is the head and N2 is a complement. Gender is thus assigned directly by the head noun to the NP in the latter case, but not in coordination.

4.4 The role of humanness

Our acceptability rating experiment shows that the preference for CCA is sensitive not only to directionality (or structural distance), but also to humanness. However, the effect of humanness is only significant in post-nominal position when adjective agreement takes place after the whole coordination phrase has been seen. This effect can be explained by the role of interpretation for human-based gender. While it is arbitrary for non-human nouns, grammatical gender is usually non-arbitrary for human nouns, and associated with social gender (Section 1.2). Note that for human nouns, especially ‘professional nouns’, their interpretation involves a social meaning. Plural masculine is ambiguous between a gender-neutral reading (i.e., referring to persons of both sexes) and a gender specific reading (i.e. referring to men only) (Gygax et al., Reference Gygax, Gabriel, Sarrasin, Oakhill and Garnham2009). les habitants (the inhabitant.m.pl) can be used to refer to a group of men and women ; however, a noun phrase with feminine grammatical gender, such as les habitantes (the inhabitant.f.pl), exclusively picks out women.

We suppose that the preference for masculine (resolution) for humans can be explained by this interaction with social meaning. For human nouns, the interpretation of a coordination involving masculine and feminine can be a mixed gender reading, leading to a preference for a (neutral) masculine adjective.

4.5 Comparison with determiner agreement

As in other Romance languages, CCA is also attested for determiner agreement in French. Abeillé, An and Shiraïshi (Reference Abeillé, An and Shiraïshi2018) tested gender agreement. Most French plural determiners are not specified for gender (les, des), so we chose certains/certaines (‘certain’) (Schnedecker, Reference Schnedecker2005). In Frantext (after year 1950: 31 millions words), we found as many tokens for certains Nmpl et Nfpl (20-a) as for certaines N1fpl et N2mpl (20-b), but no certains N1fpl et N2mpl.

In an acceptability judgement task, we tested gender agreement with the coordination of plural nouns of different genders (certains/certaines N1fpl et N2mpl), for human and non-human nouns, such as the following:

When the feminine N is the first conjunct (the closest to the determiner), we found that the feminine certaines is preferred, and that certains is rated as low as ungrammatical controls. We conclude that feminine agreement is a case of CCA and that it is the only strategy for gender agreement when the closest noun is feminine. Thus masculine agreement (when the closest noun is masculine) can also be analysed as a case of CCA. This is consistent with what we have found for prenominal adjectives.

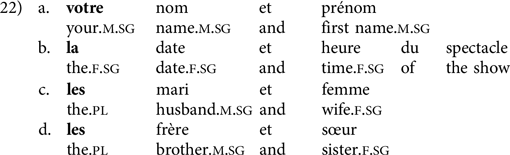

4.6 Comparison with number agreement

As for number agreement in the nominal domain, An and Abeillé (Reference An and Abeillé2017, Reference An and Abeillé2019) tested determiner (D) agreement with two coordinated singular nouns. In a corpus study (FrWac), we found that Ds (22a,22b) is more frequent (90% of occurrences) than Dp (22c,22d), even with non coreferent nouns (Ds in 71 % of occurrences with non coreferent nouns):

We also found that syntactic position plays a role: Dp is more frequent in subject position (with a plural verb) than in object position. We also ran several acceptability studies, and found an effect of humanness: Ds is slightly more acceptable than Dp with non-human nouns (votre/vos nom et prénom ‘your name and first name’), but Dp is more acceptable with human nouns (mes père et mère ‘my father and mother’). We consider singular agreement as a case of CCA, and plural agreement as a case of resolution. So humanness favours resolution, as for gender agreement. This is different from other Romance languages, which seem to prefer singular agreement for determiners with two singular coordinated nouns (Le Bruyn and de Swart, Reference Le Bruyn and de Swart2014; Heycock and Zamparelli, Reference Heycock and Zamparelli2005).

An (Reference An2020) also studied number agreement of postnominal attributive adjectives after two singular coordinated nouns (with the same gender):

In an acceptability judgement task, she found that As is as acceptable as Ap, and there was no effect of humanness. This suggests that in the nominal domain, CCA is stronger for gender than for number in French, since for number both singular (CCA) and plural (resolution) are acceptable in prenominal position.Footnote 20

5. Conclusions

A number of conclusions can be drawn from this work. We were able to show that CCA plays an important role in attributive adjective agreement, using a large corpus of contemporary French and an acceptability experiment. Contrary to the prescriptive norm, feminine agreement may be acceptable for attributive adjectives with conflicting coordinated nouns. In this respect, French is not different from other Romance languages, such as Spanish (Demonte and Perez-Jimenez, Reference Demonte and Perez-Jimenez2012), Italian (Benincà, Reference Benincà, Salvi and Frison1988) and Portuguese (Villavicencio, Sadler and Arnold, Reference Villavicencio, Sadler, Arnold and Müller2005).

Our corpus data strongly suggest that contrary to most French grammar books, closest conjunct agreement is quite frequent for noun-adjective gender agreement in French, and even the most frequent option for prenominal adjectives. Assuming a hierarchical structure for coordination (Kayne, Reference Kayne1994; Borsley, Reference Borsley2005), we suggest that the preference for CCA with prenominal adjectives may be explained by structural distance, as well as by incremental processing.

We use an acceptability rating task which shows that (feminine) CCA should be distinguished from attraction errors (Bock and Miller, Reference Bock and Miller1991; Franck, Vigliocco, and Nicol, Reference Franck, Vigliocco and Nicol2002), which do occur in spontaneous production but which are not well accepted (Fayol, Largy and Lemaire, Reference Fayol, Largy and Lemaire1994). Our experimental data also show that the preference for CCA is sensitive not only to the adjective position but also to the semantic features of nouns. Human nouns may favour resolution (masculine) agreement, especially for post-nominal adjectives. This difference may be explained by the interpretability of gender with human nouns and the availability of a masculine gender neutral plural for human nouns (les habitants may include men and women, while les habitantes do not) (Gygax et al., Reference Gygax, Gabriel, Sarrasin, Oakhill and Garnham2009). It may also be explained by the role of the prescriptive norm, which tends to take examples with human nouns (and to teach French children about boys and girls more than about tables and books).

We conclude that CCA is an independent strategy sensitive to the target-trigger ordering and to humanness as well, which confirms the typological tendencies proposed by Corbett (Reference Corbett1983, Reference Corbett1991, Reference Corbett2006), and the corpus study in other Romance languages (Villavicencio, Sadler and Arnold, Reference Villavicencio, Sadler, Arnold and Müller2005). We suggest it is the only acceptable option in prenominal position. We conclude that closest conjunct agreement may be part of the grammar of contemporary French and suggest that it should be taught as such. Further work should test predicative adjectives.

Appendices

A Experimental materials

-

1. N1m-et-N2f-A: Des agissements et interactions surprenants/surprenantes risquent d’étonner les chercheurs.

A-N1f-et-N2m: De surprenants/surprenantes interactions et agissements risquent d’étonner les chercheurs.

Q: Les scientifiques vont-ils sans doute être surpris ? A: Oui

-

2. Des procédés et solutions astucieuses permettront de résoudre ce problème.

Q: Le problème est-il résolu ? A: Non

-

3. Des départements et régions anciennes vont recevoir de nouveaux noms.

Q: Les régions vont-elles être renommées ? A: Oui

-

4. Des comportements et propriétés fabuleuses sont caractéristiques des êtres vivants.

Q: Les êtres vivants ont-ils des spécificités ? A: Oui

-

5. Des événements et activités intéressantes ont lieu dans cette enceinte.

Q: Y a-t-il une femme enceinte ? A: Non

-

6. Des ananas et cerises délicieuses sont disponibles au marché.

Q: Y a-t-il des fruits sur le marché ? A: Oui

-

7. Des appareils et technologies étonnantes verront le jour dans les années à venir.

Q: La phrase parle-t-elle de littérature ? A: Non

-

8. Des jours et nuits nombreuses seront nécessaires pour finir ce travail.

Q: Ce travail est-il facile ? A: Non

-

9. Des mensonges et vérités criantes sortent de la bouche de ces gens.

Q: Ces gens sont-ils toujours honnêtes ? A: Non

-

10. Des immeubles et maisons nouvelles vont déjà faire l’objet de rénovations.

Q: La phrase parle-t-elle de mode ? A: Non

-

11. Des tissus et matières délicates composent ces robes.

Q: Ces robes sont-t-elles délicates ? A: Oui

-

12. Des usages et règles importantes doivent s’enseigner très tôt.

Q: La phrase parle-t-elle de livre ? A: Non

-

13. Des donateurs et donatrices généreuses ont fait cadeau de leurs vêtements.

Q: Ces gens sont-ils radins ? A: Non

-

14. Des étudiants et étudiantes nouvelles sont déjà en stage.

Q: Les étudiants travaillent-ils en ce moment ? A: Oui

-

15. Des citoyens et citoyennes nombreuses attendent le dernier moment pour voter.

Q: Les électeurs sont-ils indécis ? A: Oui

-

16. Des animateurs et célébrités anciennes se retrouvent au gala de fin d’année.

Q: Le gala se passe-t-il en janvier ? A: Non

-

17. Des infirmiers et chirurgiennes courageuses effectuent des nuits de garde.

Q: Le personnel hospitalier travaille-t-il parfois la nuit ? A: Oui

-

18. Des copains et copines gentilles me donneront leurs cadeaux.

Q: Vais-je recevoir des cadeaux ? A: Oui

-

19. Des comédiens et comédiennes surprenantes rendent cette pièce incroyable.

Q: Les acteurs sont-ils doués ? A: Oui

-

20. Des adolescents et adolescentes joyeuses révisaient sur les pelouses.

Q: La scène se passait-elle dans une crèche ? A: Non

-

21. Des spectateurs et spectatrices ravissantes se pressaient à la fin de la pièce.

Q: La phrase parle-t-elle de spectacle ? A: Oui

-

22. Des acteurs et actrices élégantes ont fait leur entrée au festival de Cannes.

Q: Le festival de Cannes a-t-il commencé ? A: Oui

-

23. Des chefs d’Etat et personnalités importantes ont commencé les négociations.

Q: Les négociations sont-elles terminées ? A: Non

-

24. Des bijoutiers et créatrices fameuses présenteront leurs œuvres.

Q: La phrase parle-t-elle de cuisine ? A: Non

Control items

-

1. gram: Le fils de la voisine est content d’aller à l’école.

ungram: Le fils de la voisine est contente d’aller à l’école.

Q: Le fils est-il scolarisé ? A: Oui

-

2. Le four de la cuisine est trop crasseux pour faire à manger.

Q: Le four est-il propre ? A: Non

-

3. Le mari de ma sœur est acteur à Hollywood.

Q: Le mari travaille-t-il en France ? A: Non

-

4. L’amant de ma femme a été pris la main dans le sac.

Q: Ma femme est-elle fidèle ? A: Non

-

5. Le fourgon de la police sera vert dorénavant.

Q: Les agents ont-ils un véhicule ? A: Oui

-

6. Le rire de ma mère devient de plus en plus agaçant.

Q: Ma mère rit-elle ? A: Oui

-

7. L’entrée du palais est vraiment somptueuse.

Q: La phrase parle-t-elle d’architecture ? A: Oui

-

8. La venue du roi paraît assez effrayante.

Q: Est-ce une monarchie ? A: Oui

-

9. La cousine de mon père est dessinatrice pour enfants.

Q: Est-ce qu’un de mes parents a une cousine ? A: Oui

-

10. La vitrine du magasin semble ancienne et délabrée.

Q: La vitrine est-elle neuve ? A: Non

-

11. La place du village est déserte depuis des années.

Q: La place est-elle inhabitée ? A: Oui

-

12. La lumière du soleil devient plus chaude après 14h.

Q: Fait-il plus chaud le matin ? A: Non

B Results:

Table 4. Mean of acceptability ratings in the final analysis, after removing participants whose results don’t correspond to the criteria defined in section 3.2

C Model analysis

C.1 Effects of position

Table 5. Coefficients of the mixed-effects ordinal regression model testing effects of adjective’s position. This regression test the effects of adjectives’ position on gender agreement, with fixed effects A (Am/Af), position (pre/postnominal) and their interactions. There were also random intercepts, as well as A, position and their interactions as random slopes for subjects and items

Signif. codes: 0 ‘***’ 0.001 ‘**’ 0.01 ‘*’ 0.05 ‘.’ 0.1 ‘ ’ 1

C.2 Effects of humanness

Table 6. Coefficients of the mixed-effects ordinal regression model testing effects of humanness in the A-N1f-et-N2m position, with fixed effects Humanness (human/non-human), A (Asg/Apl) and their interactions, random intercept and Humanness, A and their interactions as random slopes for subjects and A for items

Signif. codes: 0 ‘***’ 0.001 ‘**’ 0.01 ‘*’ 0.05 ‘.’ 0.1 ‘ ’ 1

Table 7. Coefficients of the mixed-effects ordinal regression model testing effects of humanness in the N1m-et-N2f-A position, with fixed effects Humanness (human/non-human), A (Asg/Apl) and their interactions, random intercept and Humanness, A and their interactions as random slopes for subjects and A for items

Signif. codes: 0 ‘***’ 0.001 ‘**’ 0.01 ‘*’ 0.05 ‘.’ 0.1 ‘ ’ 1