The neglect of finance in the recent historiography of modern Christianity remains one of the most obvious barriers to the development of an enriched understanding of the emergence, growth and decline of church denominations.Footnote 1 This contrasts with its earlier treatment by eighteenth- and nineteenth-century political economists and churchmen of the stature of Adam Smith and Thomas Chalmers who, in their writings, offered rigorous analyses of the part played by economic and financial forces in shaping religious outcomes.Footnote 2

A complementary, and equally inhibiting, neglect is to be found in the late twentieth-century economics of religion literatureFootnote 3 whose leading contemporary scholar, Laurence Iannaccone, noted a decade ago that ‘Strange as it may seem, the economics of religion has yet to pay much attention to financial matters. In fact, one learns much more about the financial activities of religious institutions from historians, sociologists, and religious leaders, than from economists.’Footnote 4 Despite these adverse assessments, a growing number of US-based scholars have recently advanced fruitful dialogue between the disciplines,Footnote 5 framing research agendas aimed at addressing a number of poorly understood church finance-related questions. To date these have focused primarily, but not exclusively, on North American Protestant denominations.Footnote 6

In the context of Scotland, contemporary scholars have explored the general area through the lens of clearly focused and carefully researched local case studies. Examples covering different aspects of church finance in the post-Reformation period include Callum Brown's study of pew-renting in nineteenth-century Glasgow, John McCallum's survey of ministerial stipends in late sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century Fife, and J. W. Sawkins and E. Bailey's analysis of early twentieth-century ministerial stipend cross subsidy in the United Free Church of Scotland.Footnote 7 Whilst general, economic and church histories of Scotland touch lightly, if at all, on matters of ecclesiastical finance,Footnote 8 the theme surfaces often in a number of historical studies of social, political and economic events and change in the early modern and modern eras.Footnote 9 There is, however, an important exception to the broad neglect of the area in the landmark work of J. N. Wolfe and M. Pickford, claimed by the authors, with justification, to be the first comprehensive economic analysis of an institutional Church.Footnote 10

In this work Wolfe and Pickford comprehensively describe and analyse the financial affairs of the established Church in the mid-1970s, drawing on (then) contemporary data stretching back to the late 1920s,Footnote 11 in order to frame and analyse proposals designed to improve its financial position and prospects. Topics covered included: the Church's income and expenditure, financing of the ministry, fund-raising, stewardship, property and investments. This pioneering economic tour d'horizon is rich in suggested avenues for further research. However, with a very small number of exceptions,Footnote 12 most of these have remained unexplored.Footnote 13

This neglect has led to a position in which existing historical narratives of nineteenth- and twentieth-century Scottish church denominational development remain deficient in insights relating to finance; specifically those analysing the way in which economic incentives drive individual behaviour, and thereby shape organisational outcomes.Footnote 14 One of the most significant of these deficiencies relates to the returns to labour – i.e. the direct stipendiary remuneration, absolute and relative, of the clergy – the impact of this on the composition of the ministerial labour force (its quantity and quality), and whether this is causally linked to the organisation's development.Footnote 15 Absent foundational work, constructing and analysing remuneration data collected over an extended period of time on a consistent basis, this critical aspect of church denominational development, also a central and rudimentary analytical focus within mainstream labour economics,Footnote 16 is inhibited.

This paper addresses this gap in the literature in two ways. First, in relation to the question of clerical remuneration, it describes, analyses and calibrates the arrangements of the majority of the established Church of Scotland's ministers between the early nineteenth and the late twentieth century. In doing so it constructs and deploys a longitudinal and cross-sectional dataset relating to direct stipendiary clerical remuneration, materially more extensive in range and scope that those previously developed for the profession. Second, it offers the first preliminary analysis of the economic consequences for ministers and the established Church as a whole, of the process of fixing, or standardising, stipends in money terms from 1925 onwards. It thereby enriches the understanding of Scottish clerical remuneration across more than a century, and also lays the necessary foundations for future studies of the causal link between clerical remuneration and denominational development.

The paper proceeds by drawing on existing literature to contextualise a description of the system of teinds, or tithes, which, from the time of the Reformation, funded the stipends of the vast majority of the established Church's clergy.Footnote 17 The existing literature is extended through the subsequent description of the initiation and progress of stipend standardisation.

Teinds and ecclesiastical stipends

The first record of the custom of giving a tenth – or teind – of the produce of land for religious purposes in Scotland dates from the reign of King Edgar (1097–1107); the grant being made by an Anglo-Norman knight over lands in the parish of Ednam near Kelso.Footnote 18 The practice spread rapidly in the later Middle Ages, surviving the convulsions of the Reformation, to become the principal means by which stipends of Church of Scotland ministers were funded.

In Scotland the teinds were originally a separate legal ‘estate’ attaching to land, rather than a burden on land itself. They were expressed in terms of quantities of various grains grown in a locality,Footnote 19 with parish ministers legally entitled to draw an agreed fixed stipend payment in ‘victual’, that is in kind, directly from the fields. This arrangement however proved cumbersome, contentious and inefficient in operation; consequently, in 1808, a parliamentary actFootnote 20 regularised and reformed the system.

The 1808 act required teind-holders (generally local landowners) to make payment of stipend in money, rather than in victual. For this purpose valuation of the quantities of grain, in which the stipend was fixed, was made using prices set, or struck, at annually convened county fiars courts. The fiars prices varied according to type of grain, year and geographical location. Consequently the stipends of ministers rose when agricultural prices increased, and declined when they fell.

Across all parishes the minister's stipend was the primary charge against the teinds. In some parishes the whole of the teinds were applied to the payment of the minister's stipend, in which case the teinds were said to be ‘exhausted’. In other parishes ‘unexhausted’ teinds, i.e. those which were not applied to support the minister, were retained by the landowner. A legal process existed whereby application could be made for augmentation of stipend from unexhausted teinds within a parish; i.e. a transfer of the product of the teinds from the teind owner to the minister. However unexhausted teinds in one parish could not be transferred to another.Footnote 21 Consequently the value of stipend varied across parishes.

By themselves the teinds were often insufficient to supply an adequate annual income to individual parish ministers. Consequently in 1810Footnote 22 and 1824Footnote 23 parliament voted financial aid to the Church for the purpose of making up to £150 per annum stipends in parishes where the teinds had been exhausted. Nevertheless, as the process of augmentation proceeded throughout the nineteenth century, the capacity of the teinds to finance ministerial stipends progressively eroded.

Other sources of finance

Whilst the overwhelming majority of ministerial stipends continued to be funded in whole or in part by the teinds throughout the nineteenth century, three other means of finance were also in play. First, direct payment from local burgh revenues to ministers employed in over forty parish churches, located in the larger towns and cities: the burgh churches.Footnote 24 Second, payment from the government exchequer to ministers employed in forty-two parliamentary churches located in the sparsely populated and economically poor Highlands and Islands.Footnote 25 Third, stipends derived from endowments provided by voluntary donation to support the establishment of new chapels and churches in densely populated, urban areas.Footnote 26 And it was this third means of finance that grew in scale and significance from the 1830s onwards.

Despite repeated attempts by Chalmers and other leaders of the Church to persuade the government of the day to fully endow new places of worship no additional government money was secured. Consequently, funding by private, voluntary donation was sought to meet essential running costs. This church extension campaign to extend the work of the Church, in cities and other populous places, led to around 200 chapels being built between 1834 and 1841.Footnote 27

The financial position of the new chapels was, however, fragile; and was further weakened when, in 1843, a third of the clergy and up to a half of the membership left the established Church in protest over state interference in ecclesiastical affairs. Prompted to act, but still opposed to using Exchequer funds for the purpose of church endowment, the government passed legislation the following year to remove procedural barriers to the establishment of new parishes. The act of 1844Footnote 28 permitted the establishment of parishes, Quoad sacra, if an endowment sufficient for the funding of a stipend of £120 per annum could be raised. The required capital sum for each church was approximately £3,000; consequently, to fully endow all 200 chapels, around £600,000 was required.

The immense fundraising task began in earnest in 1846. Led energetically by James Robertson, professor of church history at the University of Edinburgh and convener of a General Assembly Endowment Committee, funds accumulated rapidly. By the time of his death in 1860 around £180,000 had been raised, with the campaign itself ultimately realising around £400,000 providing endowments for 150 new parish churches, many in economically deprived areas.Footnote 29

Thus, by the last decade of the nineteenth century, the overall position in relation to the financing of the stipends of ministers of the Church of Scotland was as follows:Footnote 30 in 880 parishes ministerial stipends were funded in whole or in part from teinds; in 476 parishes the teinds had been fully exhausted and no further augmentation was possible;Footnote 31 in fifty parishes stipends were financed by burghs and in forty-two parliamentary churches in the Highlands and Islands by central Government Exchequer grant; and finally, in 370 Quoad sacra parishes, stipends were funded through endowments raised by voluntary giving.

Thus voluntarily contributed endowment funds were increasingly being relied upon to fund ministerial stipends, as the capacity to secure additional finance from unexhausted teinds diminished. At the same time the Church began to call publicly for reform of the teind system, still a critical source of finance, focusing its concern on the way in which annual fiars prices were struck.

Fiars courts

Although originally required to determine the value of crown and church rents and duties, by the early nineteenth century the primary use of annually determined fiars prices had become the fixing of ministerial stipends. Scotland's county sheriffs convened fiars courts annually, inviting a jury to receive evidence on prices realised for different types and qualities of grain grown within the county at a particular point in the year.Footnote 32 From 1810 a statutory return of prices was made to the Teind Office in Edinburgh.Footnote 33 This central ingathering of information from across the country, together with information published in the local press on fiars court procedure and outcomes, revealed the extent of variation in practice as between county fiars courts, which Paterson (1852) noted to be ‘different, inconsistent and contradictory’, with the methods of striking fiars themselves ‘loose, inefficient and incorrect’.Footnote 34

The main differences in practice related to weights and measures, timing and valuation practice for varieties of grain. Prior to the passing of legislationFootnote 35 in 1824 promoting the general adoption of the imperial system, counties were at liberty to adopt different standard weights and measures. It was therefore not until 1826 that local custom and practice began to give way to a nationally-prescribed approach, a process which took several years to embed. On timing, county sheriffs were at liberty to convene hearings to strike fiars prices in different months of the year. Most took place from early February to the middle of March; however in Orkney and Shetland, for example, fiars were traditionally struck in May. Finally, on valuation, different counties valued different types of grain, with some having one price per type of grain and others having different prices for different qualities of the same grain.

These and other inconsistencies were a source of frustration and concern to the established Church and its clergy, prompting regular reports on the deficiencies of the system at annual General Assembly meetings.Footnote 36 Eventually a government departmental committee, appointed in 1911 by the Scottish Office and the Board of Agriculture and Fisheries, investigated and reported its findings:

Besides the lack of uniformity, the evidence of the agricultural bodies and of the representatives of the ministers shows that there are several points, some of them applicable to only a few counties, others more general, in which the present practice is open to grave objection. Among these are, (1) the composition of the jury, (2) insufficient quantity of evidence, (3) unnecessary burden of attendance on jurors and witnesses, (4) limitation of the evidence to too short a period of the year, (5) acceptance of evidence without a schedule of particulars, (6) want of opportunity to examine the schedules, (7) inaccurate method of calculating the Fiar of meal, (8) calculation of the Fiars by prices alone, instead of by quantities and prices, (9) acceptance of evidence of prices which include cost of carriage, (10) calculation by an artificial standard of weight instead of by the natural weight of the bushel. Under each of these heads there is evidence in one county or another of serious error.Footnote 37

The movement to reform these unsatisfactory arrangements was interrupted by the First World War. However post-war it resumed, being given new momentum by church union negotiations involving the Church of Scotland and the second largest Presbyterian denomination, the United Free Church.

Stipend standardisation and minimum stipend

In early church union discussions between these two denominations, a key obstacle to progress had been the question of the established Church's control over its property and endowments and the extent to which it was able to exercise its property rights free of state interference.Footnote 38 To put this beyond all legal doubt, the Church of Scotland (Property and Endowments) Act 1925, was passed by parliament.Footnote 39 This act transferred to General Trustees of the Church all property (churches, manses and glebes), burdens of maintenance and endowments, and made provision for the standardisation of stipend.

In relation to stipend the act abolished the link between it and the variable price of grains (victual), fixing – or standardising – the amount payable by teind holders for all time. The fixed monetary value of the standardised stipend was to be calculated using average prices for grains, county by county, over the fifty-year period 1873–1922, with the addition of a further 5 per cent The act affirmed the principle of payment in money rather than victual, requiring this payment to be made by the teind holder to the Church of Scotland's General Trustees, rather than the local parish minister.Footnote 40 The process of standardisation was to occur in one of three circumstances. First, automatically, when a parish fell vacant. Second, if requested by an incumbent minister. Third, if requested by the General Trustees of the Church.

Following years of buoyant prices immediately after the First World War, agriculture along with the rest of the economy experienced a prolonged period of depression in the 1930s. With average prices fixed under the act being substantially higher than those prevailing in the market, many ministers elected to standardise their stipends during this decade,Footnote 41 thereby reducing uncertainty relating to their income and, in the short run, securing financial advantage when compared with the teind arrangements. Consequently standardisation proceeded rapidly through both vacancy and election. Of the 880 parishes covered by the terms of the act, 778 had standardised stipends by 1940. That number stood at 840 in 1950, 870 in 1960 and 878 in 1970.Footnote 42 The last of the parish stipends to be standardised was the parish of Dunblane in 1974Footnote 43 when, under the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973, county fiars courtsFootnote 44 were abolished. This act finally brought to a close a centuries-old system of ministerial stipend payment.

A further significant stipend-related outcome of the church union negotiations was the introduction, in 1929, of a minimum stipend for ministers of both uniting branches of the Church. The amount set for that year was £300 plus a manse, with an internal transfer of church funds being the means by which ministers paid less than this amount were compensated. The 1929 Report by the Committee on the Maintenance of the Ministry to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland recorded that ‘It was estimated [pre-Union] that to raise all the Livings of the Church on behalf of which applications for grants had been received, to a minimum of £300 and a manse would require a sum of about £20,500. The Committee agree that this should be done, and that the balance required should be taken from the Vacant Stipend Fund.’Footnote 45

Minimum stipend arrangements continued in the united Church with periodic increases as funding permitted.

The typical rural parish: Blackford

Having described stipend financing arrangements in general terms an analysis of how these operated in the context of a typical rural parish is now offered, the aim being to illustrate, analyse and calibrate the changing economic fortunes of the established Church's clergy in a specific parish area from the early nineteenth to the late twentieth century.

For this purpose three key criteria are used as the basis of parish selection. First, its identification as a rural area with a predominantly agriculturally based local economy in the first (Old), second (New) and third (mid-twentieth century) Statistical accounts of Scotland. Second, its location on mainland Scotland, thereby ruling out the more remote island areas. Third, the availability of historical quantitative data relating to teinds and ministerial stipend over a period of more than a century. From amongst the subset of areas meeting these criteria, the parish of Blackford, in the county of Perthshire, is selected.

The first or Old statistical account of the parish, written by the Revd John Stevenson in 1792, in describing its rural character in detail, gave a decidedly downbeat summary of Blackford's general situation and agricultural potential. ‘The soil in the parish is not good … Some few spots, that have been long cultivated are tolerably fertile when the season is good: but the far greater part of the ground in tillage has not the smallest pretensions to fertility. But bad as the soil is, the climate is still more unfavourable.’Footnote 46

A ministerial successor, the Revd John Clark, writing the second or New statistical account gave an altogether more upbeat assessment. Writing in 1837 he stated that

The south part of the parish is traversed by the Ochil Hills and affords good pasture for sheep. The middle is formed by the extensive Moor of Tullibardine, which is covered with young plantations. The northern part consists of rich and well cultivated lands …There have been many and great improvements in the parish within the last twenty years. The chief of these the formation of roads, which opened new channels for intercourse, and supplied new means for improvement. With improvement of the soil the circumstances of the people have improved.Footnote 47

In the third (1950) Statistical survey account, authored by D. S. Stewart jp, both the arrival of the railway and some light industry were referenced. However, whilst the improved transportation links were associated in the account with changes in the way of life, Stewart noted that the population and the village itself had not increased in size or changed in character over the last century and that the local economy continued to be agriculturally based:

These local shops, joinery works and railway give employment to quite a number, but the largest number of people are employed in agriculture. A large force of workers, male and female, are engaged in planting, harvesting and marketing potatoes.Footnote 48

Records relating to ministerial stipend, maintained between 1815 and 1932 under the auspices of the parish church's kirk session, were deposited with the National Records of ScotlandFootnote 49 and have been made available for consultation in Edinburgh. They are peculiarly suited to this analysis, containing not only an (almost) uninterrupted run of annual stipend and fiars price data, but also the annual amounts actually paid in the support of stipend by the individual teind holders.

The teinds and stipend of Blackford parish

Table 1 (see Appendix) contains a transcription from the original kirk session teind records of Blackford parish. The teinds – a liability on the owners of the various named estates in the parishFootnote 50 – are expressed in the records in traditional Scottish weights and measuresFootnote 51 for quantities of victual, and in pre-decimal currency for the teinds valued in money. An 1826 House of Commons ReportFootnote 52 noted that stipend augmentation had taken place in the parish of Blackford in 1793 and 1809, with the latter exhausting the available teinds. The teind list therefore remained definitive for the period 1815 onwards. Confirmation of this is contained in the 1837 Third Report of Commissioners of Religious Instruction Footnote 53 in which a summary of the parish's teinds were (see Table 2) recorded. This record precisely matches, and thereby validates, that contained in the archived source. Whilst noting teind exhaustion it further records that the minister of the parish was not in receipt of government aid.Footnote 54

The Blackford parish stipend continued to be funded through the teinds in the traditional way until standardisation took place in the early 1930s. As was common at this time of economic recession, the process was initiated by the incumbent, the Revd Peter Milne, and was one of twenty-nine standardisations in the year 1934,Footnote 55 eighteen by election, of which Blackford was one, and eleven by vacancy.

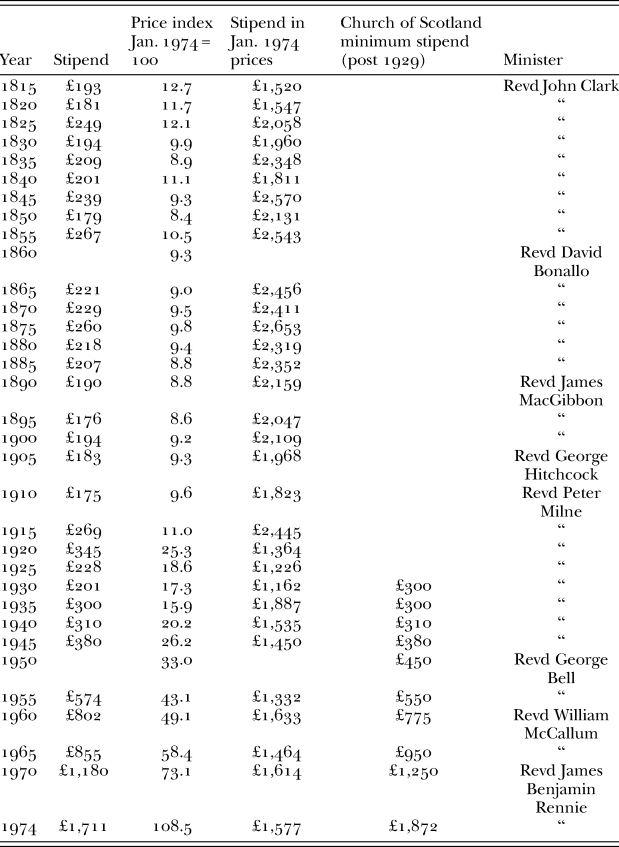

Two quinquennial stipend time series are set out in Table 3 (see Appendix) – abstracted from the annual record – for the period 1815–1974, and a third, shorter, minimum stipend series. The first is the recorded stipend as paid in nominal, or ‘money of the day’, terms to Blackford's parish minister. The second applies a composite price index, expressing the stipend in January 1974 prices,Footnote 56 thereby adjusting for general inflation. Immediately obvious from the inflation-adjusted series is the sharp fall in stipend after the First World War, a short recovery consequent on stipend standardisation, and then an extended period in which the real value of the ministerial stipend settled to a level well below that pertaining throughout the nineteenth century.

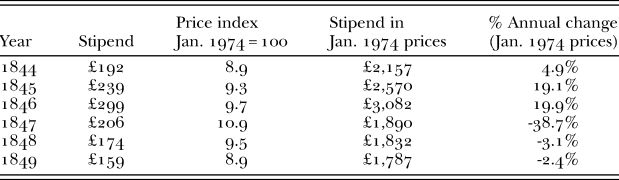

Whilst deployed for summary purposes, the quinquennial data obscures particular features evident in the annual time series. For example, periods of significant annual stipend variation, the greatest of these being around the time of the 1846–7 Highland potato famine. By way of illustration, Table 4 (see Appendix), sets out the annual stipend figures for the period 1844–9 showing the extraordinary rise and precipitous fall in stipend as it tracked the rise and fall of agricultural commodity prices in the wider economy. Other examples of sharp annual advances or reversals occur around times of economic dislocation consequent on war or recession.Footnote 57

Calibration

A number of challenges accompany attempts to calibrate stipend data extending well over a century. Chief amongst these is the availability of comparator wage time-series, collected and recorded on a consistent basis over so long a period. The problem is further compounded by the focus on a particular, sparsely populated, rural locality, which is less likely to be covered by surveyors and compilers of comparator data-series than large urban centres of population. It is necessary, therefore, to draw on multiple comparator series, relying on their complementarity to construct a calibration narrative.

Two comparator occupational groups are chosen for this purpose: first, agricultural workers and, second, fellow clergymen. The rural character of the parish and the stipendiary link, via the teinds, to the fortunes of the agricultural economy recommend the former. Clearly it is of interest to analyse the level of ministerial stipend in relation to the wages of those employed in the industry employing the greatest proportion of the parish's working population. The second comparator group, the clergy, enables light to be thrown on the question of stipend differentials in a church denomination zealous in its rejection of ecclesiastical hierarchy.

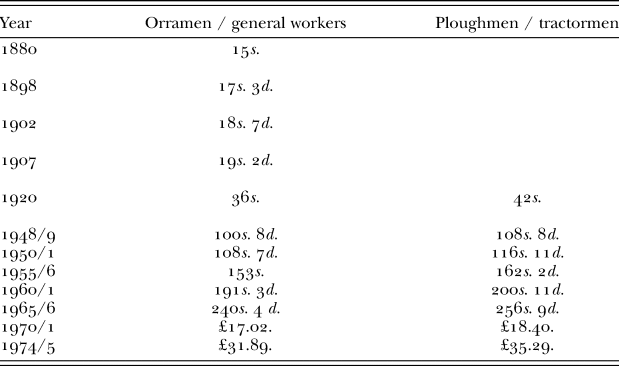

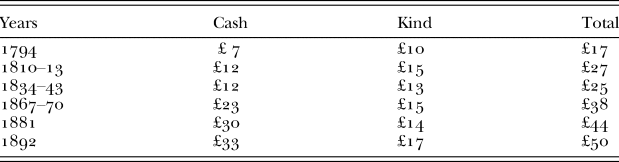

The longest available British agricultural wage time series covering this period is an annual series, beginning in 1850, for England and Wales.Footnote 58 No comparable Scottish series exists. However in Table 5 (see Appendix)a series constructed for this analysis from a number of government publications is presented.Footnote 59 The first section of the dataset, from 1880 to 1920, is a series of observations relating to agricultural workers employed in Perthshire; the second, a run of data derived on a consistent basis, relating to statutory minimum wages for agricultural workers in Scotland as a whole. To complement this, data from two important studies of nineteenth-century agricultural wages for ploughmen in the country of Perthshire are reported. Table 6 (see Appendix) draws on Bowley's (1899)Footnote 60 analysis of annual earnings (in cash and in kind) of married ploughmen, whilst Table 7 (see Appendix) offers a quinquennial extract from Houston's (1955)Footnote 61 annual time series for cash wages (excluding remuneration in kind) for the period 1814–70.

Whilst the breaks, and different collection bases across these series, inhibit precise comparison, the data are consistently of a similar order of magnitude. In view of this, a high-level approach to calibration is taken, expressing ministerial stipend as a multiple of agricultural workers’ wages.

Using the data for Perthshire ploughmen/tractormen (i.e. skilled agricultural workers) as a basis for comparison, ministerial stipend for the first half of the nineteenth century was between twelve and eighteen times that of these agricultural workers. This multiple declined as agricultural wages rose, whilst prices and therefore stipend remained level, so that by the latter half of the century stipends had stepped back to being a multiple of between six to twelve times ploughman's wages. The continuing rise in agricultural wages, supported by twentieth-century minimum wage legislation, combined with stipend standardisation fixing the nominal payment to ministers, led to an accelerated erosion of the occupational differential with the multiple falling from three times in the inter-war years through one and a half times between the late 1940s and early 1960s. Finally, parity – a multiple of one – was reached in the early 1970s; a remarkable repositioning of the relative economic fortunes of ministers over the period.

The second comparator occupational group – fellow clergymen – enables conclusions to be drawn as to the minister of Blackford's stipendiary position in relation to three sets of colleagues. First, those of the rival Free Church of Scotland who had quit the establishment at the 1843 Disruption and who had established parallel and rival networks of ministers and church buildings throughout Scotland, including within the bounds of Blackford parish itself. Second, those of the established Church serving in Edinburgh's prestigious burgh churches, whose stipends were funded by the city rather than through teind arrangements. Third, ministers of the Church of Scotland serving rural parishes, with populations similar in size to Blackford's, across all counties of Scotland.

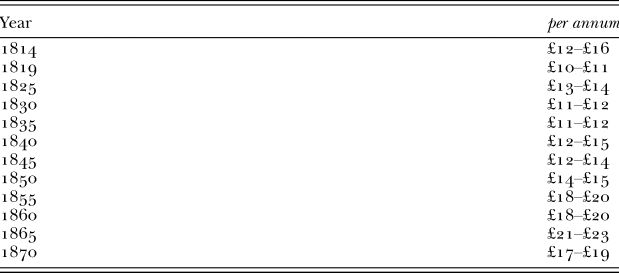

Table 8 (see Appendix) records the stipend of the minister of Blackford Free Church of Scotland from 1845 to 1900, when the Free and United Presbyterian Churches united, and Blackford United Free Church of Scotland from 1900 to the union of the United Free with the Church of Scotland in 1929. In its early years the Free Church provided the vast majority of its ministers with a minimum stipend, known as the ‘equal dividend’. From 1867 onwards a ‘surplus scheme’ operated, whereby congregations contributing according to certain thresholds were entitled to draw additional money to supplement the basic stipend. Members of Blackford Free Church of Scotland made contributions to the church's Sustentation Fund at the rate of over 10s. per member. This entitled their minister to draw the ‘higher share surplus’ as recorded in the table. From 1900 onwards the United Free Church began a process in which stipend arrangements for the uniting Churches were gradually harmonised.

Between 1845 and 1875, under the equal dividend and surplus arrangements, Blackford's Free Church minister's stipend was markedly less than his established Church counterpart; often by over £100. And whilst annual stipend variation was also less than that experienced by the established Church's minister this advantage perhaps did not outweigh the fact that the annual payments were so much lower. The gap persisted into the twentieth century and was only finally closed towards the late 1920s as the uniting Churches sought to harmonise minimum stipend levels at £300.

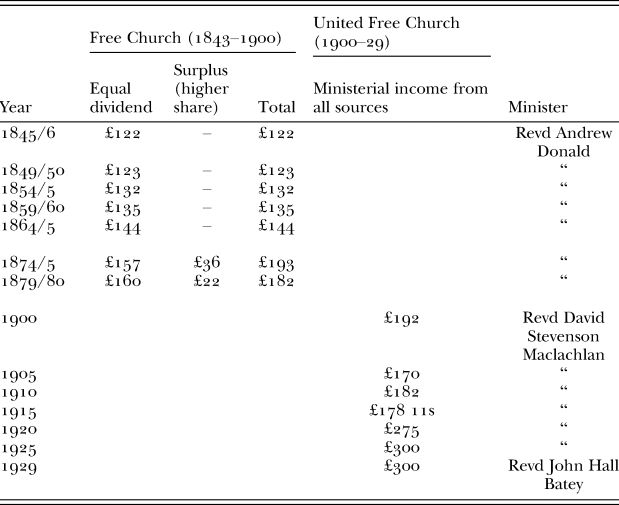

By contrast, Table 9's summary of stipends paid to burgh church ministers in the capital city (see Appendix) reveals the extent to which those employed in the prestigious city pulpits enjoyed a stipend premium over their rural counterparts. The extent of the premium, which continued well into the twentieth century, was several hundred pounds, attenuating somewhat in the later years as the effect of the post-1929 minimum stipend support came in.

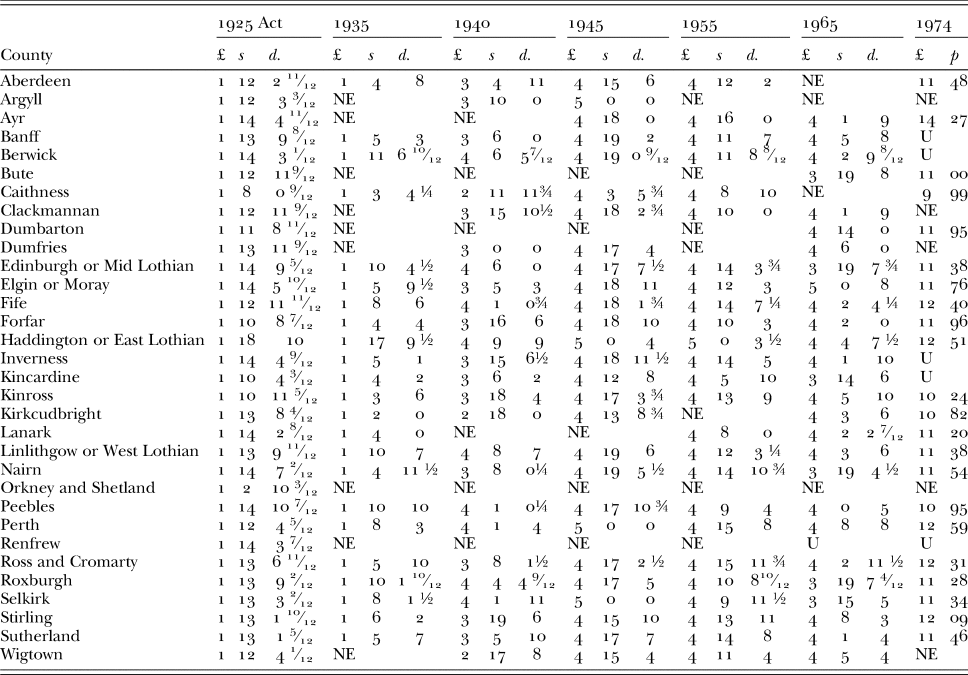

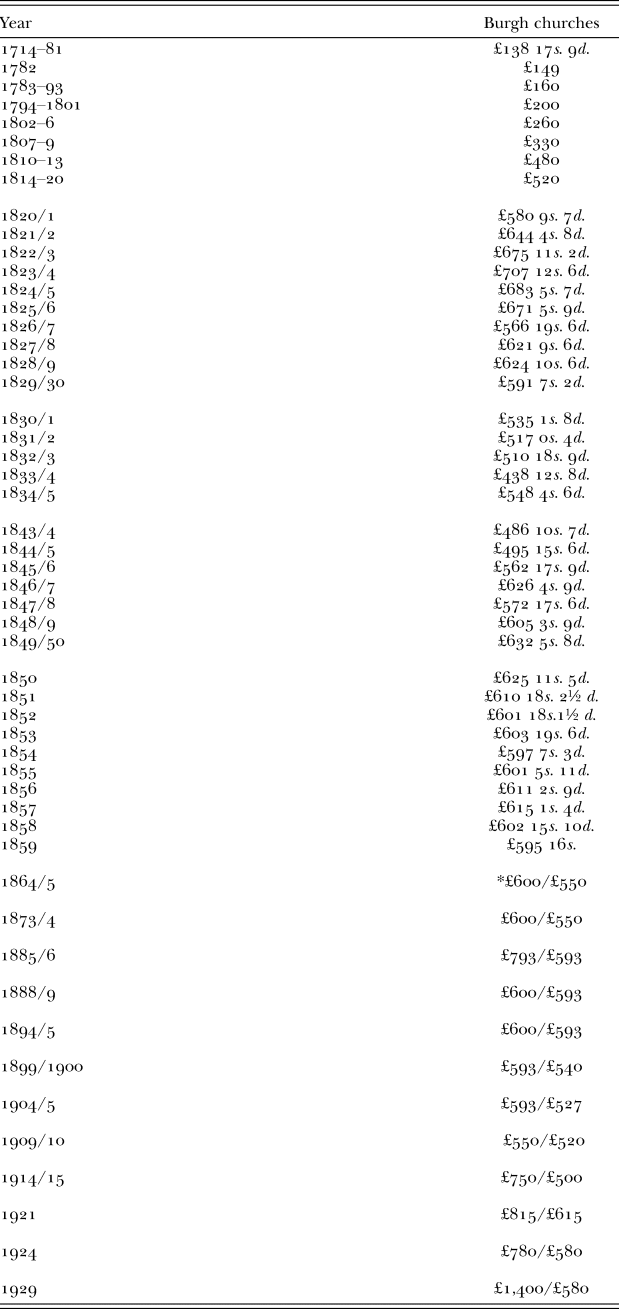

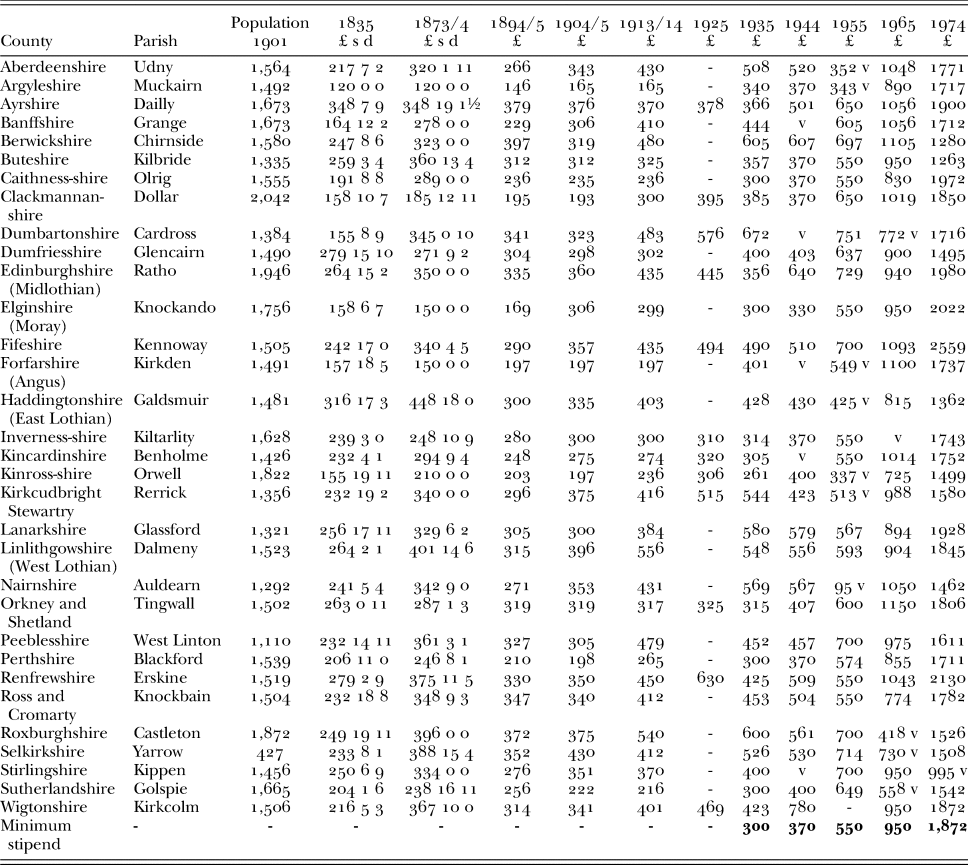

Finally, Table 10 (see Appendix) offers a comparison with parish ministers across Scotland, whose stipends, like the minister of Blackford's, were primarily funded through the teinds. This throws light on the question of the extent to which the experience in Blackford may be considered typical of rural parish ministers in other parts of the country. For this purpose rural parishes with a similar population to Blackford's in 1901Footnote 62 were identified from each of the other thirty-one county areas across Scotland in which fiars prices were struck.Footnote 63

Annual stipend data for all Church of Scotland parishes was published from the late nineteenth century in the annual Yearbook of the Church of Scotland, and then, post-1929, in annual Reports of the Committee on the Maintenance to the to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. However for data relating to the early part of the nineteenth century it is necessary to rely on various parliamentary papers which were published irregularly.

In terms of absolute stipend level and variation over time the pattern is similar across Scotland. Blackford's stipend is generally in the bottom half of those listed, tracking closely the minimum set post-Union. More generally it may be noted that in 1935, 1944 and 1955 all but one stipend of those listed was at or above the minimum. In 1965 twelve reported stipends were below the minimum; Blackford was one of them; and in 1974, during a period of rising inflation, no fewer than twenty-three out of thirty-one reported stipends fell short of the Church's minimum.

The conclusion reached in relation to the level and variability of the Blackford stipend in relation to other comparator occupational groups appears therefore to be robust with respect to representative rural parishes across the whole of Scotland. Significantly, the findings demonstrate the pace at which the relative stipendiary position of established church ministers across Scotland eroded when compared with agricultural workers.

Post-standardisation outcomes

A final point of analysis concerns the impact of standardisation on the economic fortunes of ministers in the middle years of the twentieth century.

The question of whether stipend standardisation was a strategic financial mis-step for the Church of Scotland, in view of later economic events, remains an open one. However, at the individual level, Andrew Herron recorded in his Guide to ministerial income the widely held view that ministers who chose not to standardise did eventually ‘reap considerable benefit’ but ‘they had a very long wait’.Footnote 64 In this analysis the objective is to identify when, and to what extent, the balance of financial advantage shifted away from an individual parish minister who had elected to standardise. The minister of Blackford's stipend was standardised in 1934.

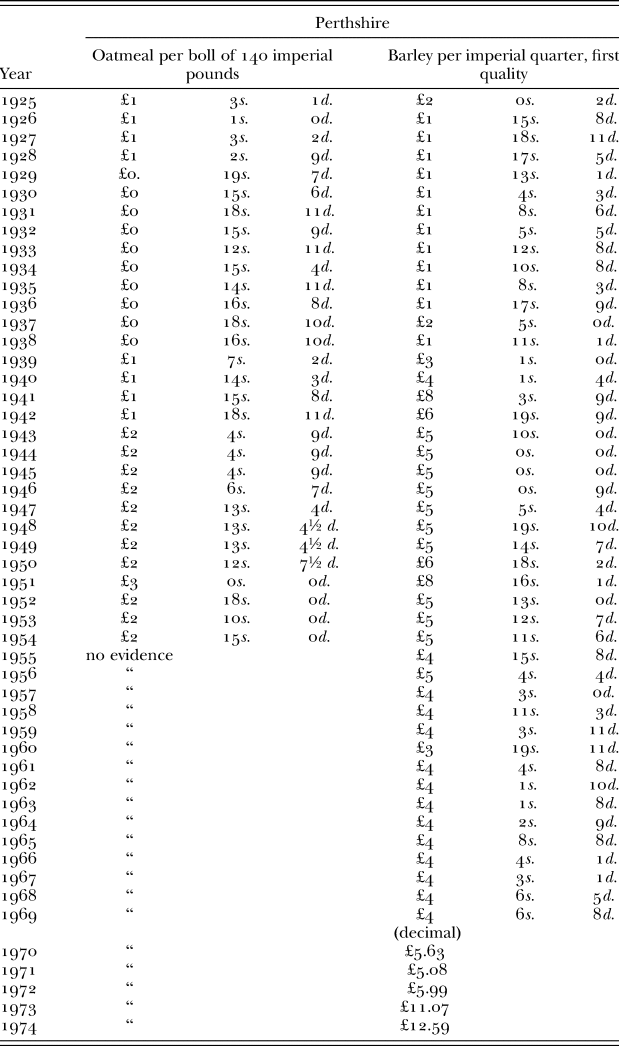

To analyse the position of the individual minister another data source, archived with the National Records of Scotland, is deployed: the Teind Court register of fiars’ prices.Footnote 65 This is a single volume, recording for every Scottish county annual fiars prices struck on an annual basis for all main grains from the mid-1820s to the abolition of fiars courts in 1974. In Table 11 (see Appendix) is extracted the Perthshire prices of oatmeal and first quality barley – using their respective traditional units of measurement; the boll of 140 imperial pounds for oatmeal and the imperial quarter. The data runs from 1925 to 1974 for barley, but only from 1925 to 1954 for oatmeal, when the local fiars court stopped collecting this evidence.

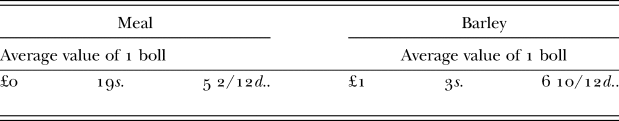

The series demonstrates a sharp fall in the price of oatmeal and a levelling of the price of barley in the 1930s. Prices rose strongly for both from the outbreak of the Second World War, with some stabilisation in the following decades, before the beginning of a sharp acceleration at the start of the 1970s. In Table 12 (see Appendix) is extracted the fifty-year Perthshire average prices for (oat) meal and barley from the First Schedule of the Church of Scotland (Property and Endowments) Act 1925. Prices for (oat) meal in Tables 11 and 12 are directly comparable, being based on the same unit of volume, the boll. An adjustment is needed for barley, where a boll may be reckoned as six bushels or three-quarters of an imperial quarter.

Considering oatmeal prices first of all, the statutory fifty-year average of 19s. 5 2/12d. exceeded the realised fiars price for the years 1930 to 1938 if the 5 per cent supplement is excluded, and 1929 to 1938 if included. For barley, reckoning the boll as three quarters of an imperial quarter, the fifty-year average of £1 3s. 6 10/12d. per boll equates to approximately £1 11s. 4d. per imperial quarter which exceeded the realised fiars price for the years 1930–2, 1934–5 and 1938, excluding the 5 per cent supplement, and 1930–5 and 1938 if included.

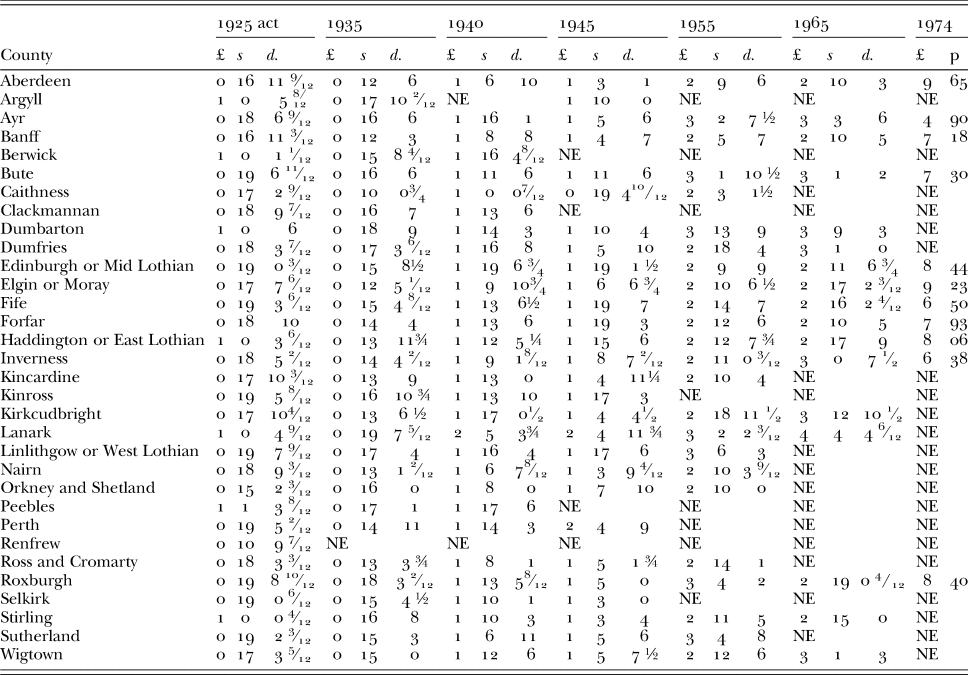

Once again it is possible to examine whether this result in the context of Blackford applies more generally. In Tables 13 and 14 (see Appendix) the prices of oatmeal and barley for each of the thirty-two county areas for which fiars were struck are listed together with the fifty-year averages of the 1925 act. In both it is clearly demonstrated that prices in 1935 were significantly lower than the fifty-year averages of the 1925 act. The situation is transformed, however, by 1940, with prices for both commodities far exceeding the fifty-year average; a position maintained and amplified as the century unfolded.

With the benefit of hindsight, what is notable is the very short length of time during which the value of grain meant that a standardised rather than teind-based stipend was to the financial benefit of the minister of the country's rural parishes. Contrary to Herron's assertion, in the case of Blackford parish, had the incumbent not elected to standardise in 1934, his annual stipend would have been considerably higher from the early 1940s onwards. By then, of course, the church's minimum stipend arrangements provided an effective floor to the stipend. However, the Church chose not to impose an upper ceiling on stipend throughout this period, to the great financial benefit of the small number of ministers whose stipends remained teind-based until final abolition in 1974.

The economic fortunes and social positioning of Scotland's clergy during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries remains an area of relative neglect in the literature, despite the profession's prominence in social and wider civic life, and the richness of quantitative and qualitative data available to researchers. Critically, little has been written on clerical remuneration per se, and any link between the composition of the ministerial labour force and general denominational development.

This paper presents foundational work, advancing understanding of ministerial remuneration for rural parish clergy of the Church of Scotland between 1815 and 1974 through a calibrated analysis of the absolute and relative level of stipend. Key findings relate to the timing and extent of the erosion, in relative terms, of clerical remuneration throughout the period, and the financial impact on ministers and the Church more generally of the process of stipend standardisation.

Thus, by the last quarter of the twentieth century ministerial stipends had reached a level broadly equivalent to the wages of skilled agricultural workers, a material erosion of their relative position explained by the process of stipend standardisation and the introduction of minimum wages for rural workers in the early twentieth century. Furthermore, the analysis offers a preliminary view of the extent to which stipend standardisation in the 1930s progressively undermined the financial foundations of the established Church of Scotland. Taken together, these results not only underline the importance of giving greater prominence to ministerial remuneration as a critical explanatory variable within narratives of denominational decline, but they also open up the field to future analyses of the relationship of ministerial remuneration to organisational development.

STATISTICAL APPENDIX

Table 1: Teinds of the heritors of Blackford

Table 2: Parish of Blackford: gross amount of teinds belonging to the crown

Table 3: Stipend, 1815–1974: money of the day and in January 1974 prices

Table 4: Stipend, 1844–9: money of the day and in January 1974 prices

Table 5: Agricultural workers: average weekly earnings (Scotland)

Table 6: Estimated annual earnings of married ploughmen. Perthshire

Table 7: Cash wages of Perthshire ploughmen, 1814–70

Table 8: Free and United Free Church ministerial stipend, Blackford parish (nominal)

Table 9: Edinburgh burgh church stipends

Table 10: Rural parish stipends by county

Table 11: Perthshire fiars prices, 1925–74

Table 12: Average fiars prices: Perthshire, 1873–1922 (1925 act).

Table 13: County prices of (oat) meal (per boll), 1925–74

Table 14: County prices of barley (per imperial quarter), 1925–74