INTRODUCTION

On the evening of March 18, 2014, Taiwanese university students and NGO workers stormed the assembly hall of Taiwan's legislature. Their occupation of Taiwan's capitol initiated a 24-day social movement—the Sunflower Movement. The protest was a desperate attempt to block the opaque review and ratification process of the Cross-Strait Services Trade Agreement (CSSTA) with China. When the movement ended, it had successfully postponed the verification process of the trade pact indefinitely.

Observers do not dispute the social movement's influence in this case (Rowen Reference Rowen2015). What is disputed is the mechanism, the causal pathway, by which the social movement exerted its effect. How did the movement succeed in influencing public policy? Since most participants were students and NGO members, they had limited financial and political resources to influence policy change. Therefore, many believe the movement had achieved its success in blocking the ratification through the assistance of political allies external to the movement. In fact, previous work has offered some evidence supporting the argument that an alliance with political elites often helps social movements achieve policy goals (Giugni and Passy Reference Giugni and Passy1998).

The dispute centers on what drives these important alliances. In the case of the Sunflower Movement, the emerging consensus in the literature argues that movement activists utilized a rivalry between top leaders of the then-incumbent party—the Kuomintang (KMT)—to leverage influence. Ho argues: “In fact, it was largely due to the personal rivalry between Ma Ying-jeou (Taiwan's ex-president) and Wang Jin-pyng (ex-president of Taiwan's Congress) that protesters were able to take hold of the plenary conference chamber on March 18 and also conclude their protest with a claim of success on April 10” (Ho Reference Ho2015, 92).

While the elite-rivalry argument is widely shared, it neglects the influence of public opinion in the movement's success. Since the movement received substantial public support from the beginning, the voice of the public could also force decision-makers to comply with the public's policy preferences. Although Ho included poll results for public support and disapproval of the movement, the mechanisms by which public opinion could influence policy-makers is not his focus. Thus, there is still a possibility that the elite alliance with activists that he identifies as important for the movement's success may have been driven by public opinion. I argue that more careful specification of this mechanism better shows the influence of public opinion. Thus, this paper reexamines the Sunflower Movement with an eye to offering a more specific account of how social movements can work through public opinion to affect public policy.

I present original data from interviews conducted in Taiwan regarding critical decisions made by political leaders, especially the ex-president of Taiwan's legislature, Wang Jin-pyng, and secondary information from newspapers and reports. I conclude that public opinion, as opposed to the Ma–Wang elite rivalry, was the major reason for the emergence of the elite alliance and subsequent success of the Sunflower Movement. Throughout the course of the movement, public opinion helped shape Wang's critical decisions: both to eject activists with police force from the legislature and to announce the decision to postpone the verification process. The former helped the movement gained momentum and the latter enabled them to achieve their political goal of blocking the trade pact.

Elite rivalry is an insufficient explanation for the alliance for two reasons: 1) the unpredictability of social movement outcome, and 2) the risks of following the path guided by the personal rivalry. When the Sunflower Movement first started, it was not clear to anyone including Wang how it would develop. It is unlikely that Wang would have decided to ally himself with activists solely based on his personal rivalry with Ma and without assessing public support for the movement. Additionally, blindly following the steps guided by elite rivalry to thwart Ma's plan to pass the trade pact could have brought political risks to Wang. In spite of his personal rivalry with Ma, Wang still had many supporters inside his own party. Deviating from the party's default stance of supporting the movement, just to weaken Ma's political power, could have alienated his supporters inside the party. In short, attributing Wang's alliance to elite rivalry incorrectly amplifies its role in the movement's success. As a seasoned politician, Wang made his decisions by learning about public opinion before deciding his own position with respect to the movement.

This study contributes to our understanding of the conditions under which social movements can make an impact on policy. It shows that the voices of the masses can be more important than political factors such as elite rivalry in elite decision-making. Broadly, this article expands a growing body of work that challenges social movement models that focus mostly on political or intra-legislative factors, to the exclusion of public opinion, as their main variable of interest in explaining movement outcomes (Burstein Reference Burstein1998; Manza and Brooks Reference Manza and Brooks2012). As demonstrated, without evaluating the influence of public opinion, the storylines behind those studies may have been oversimplified.

MEDIATORS OF SOCIAL MOVEMENT SUCCESS

Although several factors, such as mobilizing structures and framing of a movement, have been found to influence a movement's outcomes (Gamson Reference Gamson1975; McCarthy and Zald Reference McCarthy and Zald1977; Snow et al. Reference Snow, Rochford, Worden and Benford1986; Tarrow Reference Tarrow1994; McAdam, McCarthy, and Zald Reference McAdam, McCarthy, Zald, McAdam, McCarthy and Zald1996), there has been a growing interest in understanding how alliance with political elites helps social movements achieve their goals. Scholars working on this strand of research make the assumption that movements cannot realize their political objectives alone. Instead, their policy successes are often mediated by factors external to the movement itself, such as internal division among political leaders or public opinion. These factors form the basis for an alliance between elites and social movements. Research shows that when movements have institutional actors as allies on their side, they are often more likely to achieve their policy goals (Amenta, Carruthers, and Zylan Reference Amenta, Carruthers and Zylan1992).

There is an ongoing debate, however, as to which external factor (elite rivalry or public opinion) carries the most significance for the emergence of elite alliances so critical to movement success: what makes these elites receptive to social movement demands? Scholars focusing on elite rivalry argue that when elites are fractured, have a personal rivalry, or have second thoughts about current political institutions, instabilities arise (Field, Higley, and Grøholt Reference Field, Higley and Grøholt1976). Alliance with a social movement may serve to check the political opponent's power. As a result, movements are more likely to succeed when there exists disagreement within a political party, resulting in political alliance with the movement (Burton Reference Burton1977; Amenta, Carruthers, and Zylan Reference Amenta, Carruthers and Zylan1992; Amenta, Halfmann, and Young Reference Amenta, Halfmann and Young1999; Amenta, Caren, and Olasky Reference Amenta, Caren and Olasky2005; Ho Reference Ho2015).

Ho builds his explanation of the Sunflower Movement's success on this idea. In addition to other important factors responsible for the movement's success (e.g. support from the opposition Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), the urgency the activists felt about the bill passing, and the radical means of protest by occupying the legislature), he argues that the internal split within the incumbent party between the top two leaders was the major reason for the social movement's ability to take hold of the plenary conference chamber on March 18 and claim success on April 10 (Ho Reference Ho2015, 92). In other words, elite rivalry led Wang to become an ally to the movement and helped it achieve success.

Ho's explanations, however, do not give enough credit to the role that public opinion played in the movement. Since the movement carried broad public support from the beginning, the alliance between elites and the movement may also have been sparked by supportive public opinion. Studies show public opinion can motivate politicians to align with social movements. Leaders pay attention to public opinion to ensure political survival. In practice, public opinion has been found to influence a wide spectrum of issues—foreign policy, military spending, immigration policy, and women's equality (Gelpi, Feaver, and Reifler Reference Gelpi, Feaver and Reifler2006; Burstein Reference Burstein2003; Costain and Majstorovic Reference Costain and Majstorovic1994; Page and Shapiro Reference Page and Shapiro1983; Hartley and Russett Reference Hartley and Russett1992; Burstein and Freudenburg Reference Burstein and Freudenburg1978). Burstein, an expert on how public opinion influences social movements, summarizes the impact of public opinion on social movement outcome succinctly: the occurrence of a social movement moves public opinion, which then leads to a change in legislation (Burstein Reference Burstein, Giugni, McAdam and Tilly1999).

Public opinion studies also refute the argument that public opinion can easily be manipulated by political elites. In fact, the causal chain seems to work the other way around. Politicians are influential only if they agree with the public; when they disagree, the public has the say on policy (Burstein Reference Burstein2003); or, as Stimson, Mackuen, and Erikson (Reference Stimson, Mackuen and Erikson1995) state, when public sentiment shifts, political actors often sense the shift and alter their behavior accordingly. Even institutions set up to manipulate public opinion in democracies often have the inadvertent effect of leading leaders to comply with public opinion (Jacobs Reference Jacobs1992).

But, under what circumstance is public opinion most influential on policy? Studies also point out that the salience of an issue determines the impact of public opinion. A salient issue is more likely to attract the public's limited attention. After an issue receives public attention, citizens still need to form a clear stance for public opinion to be effective. It is when the public expresses a clear position on a salient issue that leaders are propelled to adhere to their voice (Burstein Reference Burstein2003).

The effect of public opinion on policy takes time to materialize, however. Even in established democracies such as the United States, public opinion takes years, if not decades, to be reflected in legislation and subsequent policies. For example, although the public in the US expressed support for gay rights policies as early as late 1990s (Brewer Reference Brewer2003), it was not until recently, almost 20 years later, that basic human rights such as marriage became protected among members in the group.

There are several reasons to expect that public opinion could in fact move public policy faster in emerging democracies. Although research confirms the importance of political identification in influencing public opinion in young democracies, attitudes toward social issues tend to be volatile and are often influenced by political events (McCann and Lawson Reference McCann and Lawson2003; Baker et al. Reference Baker, Sokhey, Ames and Renno2016). In order to secure their political interests, elites in emerging democracies are motivated to 1) be more sensitive and responsive to information and polls, and 2) react more quickly than their counterparts in established democracies to win popular support.

In the case of an emerging democracy like Taiwan, there are numerous instances in which the government responded to social protests and their requests rather quickly. For example, in 1990, when Taiwan was transitioning from an authoritarian regime to a democratic one, students from universities initiated the Wild Lily Movement to call for a more rapid political reform. The movement attracted a high degree of public attention. Rather than neglecting the development of the movement, President Lee Teng-hui, swiftly met with the student representatives and promised to enforce their suggestions, ending the protest in less than a week (Wright Reference Wright1999). A major reason why Lee reacted so quickly is the worry that delay in responding to social movement might endanger the stability of the civil society and regime and bring negative electoral consequences in upcoming elections.Footnote 1

In short, our discussion of elite rivalry and public opinion leaves us with two views of the formation of political alliances with social movements. The elite rivalry school argues that an internal split within the incumbent party, resulting from a personal rivalry between top leaders, motivates politicians to side with the movement, while I argue that the voice of the people, when salient, can lead to a quick political response from relevant political elites in an emerging democracy like Taiwan. The contextualized hypotheses with the Sunflower Movement are as follow:

Elite rivalry: If an elite disunity exists within the Kuomintang party (KMT), it will motivate some leaders within the party to take a favorable stance toward the movement.

Public opinion: If the public considers the protest and the occupation of the legislative hall to be a salient issue, with most of the citizens supporting the activists, then politicians will respond to the public's preferences and support the movement.

RESEARCH DESIGN

METHODS

Testing the above hypotheses requires information about public opinion, elite rivalry within the incumbent party, and the decisions key political leaders made throughout the movement. The short duration of the movement enables an in-depth tracing of all major events and decisions made by political leaders. Process-tracing is a commonly used method in qualitative research, as it enables researchers to track events as they unfold to increase claims on causality (Collier Reference Collier2011).

I have collected evidence from published accounts, mostly from newspapers and reports of the movement. However, secondary sources are limited in providing evidence to assess the chains of causality for some critical decisions politicians made during the movement, for example Wang's critical decisions throughout the movement.Footnote 2 To understand Wang's decision-making process between May and June 2016, I conducted in-depth interviews with political elites and their staff members in Taiwan. My interviewees include several legislators from major political parties and their staff members. In addition to the KMT and the DPP, I spoke to representatives of a new rising party formed after the Sunflower Movement, the New Power Party (NPP). (For information about interviewees, consult the Appendix.) All my interviewees were to some extent involved in Wang's decision-making process throughout the development of the movement—some directly while others in only an ancillary manner. Their knowledge of the norms, rules, and networks within the legislature makes them the most appropriate interlocutors to weigh in on Wang's decision-making during the movement. Semi-structured interviews were tailored to reconstruct the process of Wang's decisions, with emphasis on the relative importance of elite rivalry or public opinion. To corroborate my understandings of the events during the movement, I interviewed several of the activists involved.

ISSUE SALIENCE

For measuring issue salience, I follow Epstein and Segal's method of focusing on the coverage given to an issue daily by the media. In their study of US Supreme Court, they tallied the number of judges appearing on the front page of The New York Times (Epstein and Segal Reference Epstein and Segal2000). I apply the method to gauge the Sunflower Movement's salience among the public. Similarly, I record the frequency with which the movement appeared on the front page of major newspapers across different political ideologies in Taiwan, including the Taipei Times, The Liberty Times, Apple Daily, The China Times, and The United Daily News. Frequent coverage on the front page serves as evidence of salience of the movement.

PUBLIC SUPPORT FOR OCCUPATION, TRADE PACT, POLITICAL PARTY AND THE PRESIDENT

I examine four strands of public opinion. First, public support for the movement is measured by the percentage of approval and disapproval for the activists’ occupation of the legislature. Additionally, I examine three other key pieces of public opinion: support for the trade pact, approval rate for President Ma, and approval rate for the then-incumbent Kuomintang party.

Since systematic and continuous polls by the Taiwanese government or academic institutions during the protest period do not exist, I rely on various sources as best estimates of public opinion during the movement. The polls reported below come from major TV stations such as Television Broadcasts Satellite (TVBS), government agencies, and research institutions in Taiwan. The polls by newspapers agencies are trustworthy for several reasons. First, the newspapers and TV stations from which I draw polls have a public opinion poll center to conduct polls regularly. They release their survey methodology along with their polls to demonstrate the reliability of their results. Potential partisan bias is also reduced by including polls from different TV stations and newspapers.

POLITICAL ALLIES AND ELITE DISUNITY

Political allies are political players whose actions help social movements achieve their political objective, whether they are sympathetic with the movement or not.Footnote 3 Thus, I focus on political leaders whose actions assisted the Sunflower movement in achieving their political objective. However, more emphasis will be put on KMT leaders for various reasons. First, DPP politicians were supportive of the movement and student organizers from the beginning, making them default allies of the movement. However, compared to the KMT, DPP was a minority party in 2014. Although it could stall the verification process of the trade pact, it did not have enough seats for a countering bill. Before the movement started, DPP legislators had been protesting the verification process for months, but their efforts did not stop the bill from moving along the verification process by the KMT.

Unlike the DPP, the KMT held over half of the seats in the legislature during the movement, including the presidency. Their advantageous position in the legislature gave them more influence than the DPP on the movement's outcome. Additionally, the KMT was opposed to the movement from the beginning. As a result, tracing whether responses to the movement among key KMT leaders changed throughout the movement offers more insights into the impact of political alliance, as those alliances might bring changes to the prospect of the verification of the bill. Powerful allies are politicians who hold a leadership position in the legislative or executive arena during the moment, such as the president, vice president, the president and vice president of the legislature, the leader of the Executive Yuan, and the party whip. To capture arguments about elite disunity, I focus on the fragmented leadership inside the KMT, often known as the Ma–Wang rivalry. Specifically, I analyze the impact of the Ma–Wang rivalry to see what influence that could have on the movement's outcome.

HOW PUBLIC OPINION SHAPES MOVEMENT OUTCOME

The president of the legislature, Wang, has been considered by many as the most critical elite ally of the movement. But the alliance between Wang and the social movement did not come naturally. As a KMT leader, Wang's default position was to oppose the movement. However, over the course of the movement, Wang shifted his stance gradually from observing to passively tolerating to finally allying with the movement. Several days before the movement ended, he made a tide-turning announcement in which he promised that he would not hold more inter-party meetings on the trade agreement until a legal mechanism for conducting reviews of legislation concerning cross-Strait relations—a critical element of the movement's requests—was set in place to monitor the process.

Given both parties’ polemical views on the legislation at that time, a legal mechanism that both parties could agree would take a long time to form. As a result, Wang's statement helped the activists achieve their goal, as the prospects of the bill's verification were greatly reduced. Unsurprisingly, after Wang's announcement, the leaders of the movement announced their decision to exit the legislature two days later, claiming that they had achieved a temporary political goal. Wang's speech surprised many inside his party, including the president. The KMT deputy secretary commented on the effect of Wang's speech bluntly—many felt “betrayed and sold out” (Hsiao Reference Hsiao2014).

What was the rationale behind Wang's alliance with the movement? The conventional wisdom points to an existing rivalry between top leaders in the KMT (Ho Reference Ho2015). The rivalry between Wang and the ex-president went back to 2005, when they both were eyeing the leadership of the party. In 2013, President Ma, as the chairperson of the KMT, accused Wang of influence-peddling and, in an internal party meeting held while Wang was attending his daughter's wedding in Malaysia, he suggested the nullification of Wang's membership as punishment (Wan Reference Wan2013; Matsuda Reference Matsuda2015). Upon returning to Taiwan, Wang took legal steps to ensure his political rights and position as the head of Congress. Arguably, the bad history between Ma and Wang may have motivated Wang to help the activists to sabotage Ma's political power.

There are several flaws in this explanation. First, it neglects the role of public opinion throughout the movement. The public had been supportive of the movement since its inception, and the salience of the movement is evidenced by the frequent coverage of the protest throughout the 24 days of protests: it appeared on the front page every day in every major newspaper: Apple Daily, The Liberty Times, The Taipei Times, The China Times, and The United Daily News.

Figure 1 shows public support for the occupation of the legislature over 12 time points throughout the protest period from March to April 2014. The movement received a high level of support from the beginning. Public support took a deep dive in early April, most likely because a nationwide rally on March 30 did not win any significant compromise from the government, casting a negative light on the prospects of the movement. A poll conducted several days after the March 30 rally revealed that over half of respondents (56%) suggested the activists should leave the legislature (TVBS 2014c). The decline in public support for the movement was reversed again in early April. Support for the movement recovered, likely due to the appearance of a countermovement using threats of violence against unarmed activists, triggering sympathy for the movement. In addition, the public began to learn about negotiations across parties that could potentially help the movement achieve its goal. The public was hopeful again that the movement could succeed in their political goal.

Figure 1 Public Support for Occupation of Taiwan's Legislature in 2014

Figure 2 charts the level of public support for the trade pact and shows that disapproval of signing the trade pact was consistently higher than support of it since the movement began. Public opinion on the trade pact did not fluctuate as much as support for the occupation, meaning that the public did differentiate between their viewpoint on the trade pact and their preference for the movement, which seemed to be influenced more by events that happened throughout the movement.

Figure 2 Public Support for Cross-Strait Services Trade Agreement

EVIDENCE FROM INTERVIEW WITH ELITES AND ACTIVISTS IN TAIWAN

The polls on public support for the occupation and signing the trade pact show that the movement received enough support to trigger an alliance with political elites, but the mechanism through which the alliance came into existence is unclear. To understand how public opinion influenced the movement's outcome and elite's decision-making, I conducted interviews with political elites and their staff members directly or indirectly involved in the movement. Overall, all my interviewees consider public opinion to be the most important factor in Wang's decision-making process throughout the movement. They argue that Wang was mindful of public opinion about the occupation of the legislature from the movement's inception.

Specifically, public opinion motivated Wang to make two critical decisions benefitting the movement: the decision not to evict the activists from legislature and the announcement to discontinue the verification process. Both decisions are surprising, because they deviate from the default decisions that Wang was expected to make as a KMT elite. However, clear trends in public opinion changed his mind as the movement progressed.

FIRST CRITICAL DECISION: NOT TO EJECT ACTIVISTS WITH POLICE FORCE

During the first several days of the movement, Wang faced a critical decision as to whether he should eject activists with police force and restore order to the legislature. According to my interviewees, as president of the legislature, Wang felt pressure from his party to do so (Interview 2016). Rather than complying with this decision, Wang stayed out of the public eye in the first two days, even when the activists were fending off attempts from police to remove them and calling for Wang to stop the police actions. Reflecting on his reticence, my interviewees point out that Wang was assessing initial public response to the movement:

[I]n the first nearly 48 hours, Wang made no comments with respect to his positions to the movement. Why? Because he was observing the tide of public opinion to determine his responses to the movement. As it became clear that the movement had a high level of public support, Wang started to consider what decisions should be taken to respond to the movement in a way that could fit his political interests. He knew that if he made a hasty decision without taking the public into consideration, he may be held responsible by the public and face political consequences (Interview 2016).

After taking in the first several polls of the movement, Wang made an announcement on the evening of March 20, three days after the occupation started, that he “would not consider having them (activists) removed by force” (Shih, Su, and Chung Reference Shih, Fang-Ho and Chung2014). Wang's announcement ran counter to the expectations of many within his party, as they had expected him to follow the party line of ousting protestors with police force. Public opinion helped Wang to plan his actions to reduce negative consequences from his political decisions.

SECOND CRITICAL DECISION: ANNOUNCEMENT TO DISCONTINUE THE VERIFICATION PROCESS

The effect of public opinion on elite decision-making is evident even when it turned against the movement. The second decision came at a time when support for the movement had plummeted. If a high level of support for the occupation motivated Wang to side with the movement by not evicting the students, then decreased support should have prevented him from further supporting the movement. However, Wang's announcement was seen as supporting the movement and helping it succeed. How do we make sense of this?

As in the first decision, Wang's decision-making is constrained by his political environment. Wang learned that support had dropped at the end of March due to the impasse between the movement and the government. He was aware that the public was growing impatient with the dysfunctional legislature, and that, as president of the legislature, he might pay a political price for the continuing impasse. Wang also could not count on the movement dissipating, as leaders had no plans to end the movement when the support diminished (Shih Reference Shih2014). Commenting on Wang's political environment, one of my interviewees noted, “Wang understood the mass had turned from supporting to disapproving the movement and he needed to bring an end to it [the movement]. He also knew that, if the impasse between the activists and the government continued, he would be the target of criticism and might lose his position as president of the legislature” (Interview 2016).

Although Wang knew that he had to find a way to end the movement, there were few viable options. Before making the announcement, Wang had failed in six consecutive attempts to reach a compromise between major political parties. He was unable to change the prevailing KMT consensus that the movement should end and the verification process should continue. KMT leaders such as the ex-president remained adamant in their support for the trade pact.

Removal of activists by police or military force is a common tactic by the KMT government to deal with activists, but the Sunflower movement differed from other social movements in its high public support. Wang also knew that such a tactic would not work. Several days after the occupation started, the government used police force to crack down on protestors attempting to occupy another government agency, resulting in over 100 injured protestors and public uproar. The public also was unsupportive of using similar tactics: only 39 percent of the public supported Wang using similar tactics to end the movement (TVBS 2014c). Wang was careful not to make the same mistake.

Mindful of these constraints, Wang came up with a decision that would ensure his political interests without complying with the activists to the full extent by halting the verification process. The announcement was ingenious, as it offered political benefits to different parties. For the KMT, Wang's decision was unsatisfying, but it did not rule out the possibility that the verification process could be revived. For the activists, the announcement gave them a political victory for securing a substantial policy concession from the government. For the public, the announcement and the end of the movement meant that order would be restored in the legislature. For Wang, this decision allowed him to be the peacemaker between the government and activists and secured his political interests.Footnote 4

In both critical decisions, public opinion shaped Wang's considerations of political interests. As Wang might have anticipated, his decision to alleviate public anxiety about the stalled situation between the government and the social protest won public support: 65 percent of respondents supported his proposal (TVBS 2014d).

WHY ELITE RIVALRY WAS NOT THE MOST IMPORTANT FACTOR

The importance of elite rivalry is more restricted than previously thought. As public opinion guided Wang in the critical decisions, elite rivalry operated only as a part of the broad political context that Wang had to consider throughout the movement. Elite rivalry closed some doors to solving the political crisis, such as the possibility of collaborating with the ex-president on this issue, but it was not the main reason behind Wang's decision-making. In fact, the impact of elite rivalry on Wang's is exaggerated for two reasons: the unpredictability of social movement outcomes and the risks associated with following the path as guided by elite rivalry.

When social movements start, few can know how they might develop. The Sunflower movement is no exception. My interviewees noted that at the early stages, few politicians knew how it would develop—and Wang was no exception. In this situation, any misstep aimed at reducing the ex-president's political power due to elite rivalry by allying with the movement could easily backfire and hurt Wang's political interests. Retrospectively, Wang's plan succeeded in reducing Ma's political power. However, it is possible to imagine other scenarios that would have hurt Wang's political interests. For example, if the movement had received little public support, then Wang's decision to ally himself with it would have been seen as creating chaos and wasting public budget in the legislature. In a different scenario, Ma could find ways to sabotage Wang's efforts by working out a solution with activists without Wang. In short, as a seasoned politician, it is unlikely that Wang made his decisions solely based on elite rivalry, without consulting public opinion to see whether the movement could succeed.

In addition to the unpredictability of the movement's outcome, relying on elite rivalry could have had other risky consequences for Wang. Most importantly, making his rivalry with Ma a basis for supporting the movement would alienate Wang from peers and would create more enemies inside his own party. As my interviews illustrate:

It (elite rivalry) is not the reason Wang made such a decision because it entails too much political risk. Wang analyzed the situation rationally. He knew that most in his party wanted to push for ratification, not just Ma. So, choosing the activist side would mean turning back on his comrades, especially since many of them in the party, like Wang, are more pro-Taiwan. Wang would not abandon his base in the KMT just to get back at Ma. He made that decision (announcement) because he had to—the public wanted him to end the movement (Anonymous 2016).

In addition to the above reasons, Wang had little reason to sabotage Ma's political power, as the ex-president was already encountering challenges of his low approval rate. Ma's approval rating has been declining since the beginning of his second term. At the time of the protest, his approval rate was only 12.3 percent (Taiwan Indicators Survey Research 2014). Ma's low approval rating can be attributed in large part to his negligence on social issues (Ho Reference Ho, Cabestan and DeLisle2014), which influenced how activists conducted protests. The repeated nonresponse from the government motivated activists to employ more radical approaches to gain public attention, such as lying on the rail to block a train from coming to the station or fasting for a prolonged period until passing out.

Protest against the trade pact followed a similar path. Before the occupation of the legislature, many NGOs and social groups had been calling for more careful review of the trade pact to deal with potential negative consequences. When their voices were not responded to by Ma, the activists decided to take a more radical protest method. The protest is salient also because the public in Taiwan had been concerned and anxious about his proposals for economic cooperation and integration across the Strait. The trade pact was especially sensitive because it required Taiwan to open its market for Chinese investment. The public's grave concern is evidenced by a poll, conducted several days after the occupation started, reporting that 63 percent of respondents thought the government should revoke the trade agreement and restart the negotiation with China. However, Ma remained adamant in pushing for the verification of the trade pact, and his approval rate dropped another 7 percent during the movement (TVBS 2014a).

WHY DID WANG REACT TO PUBLIC OPINION, BUT MA DID NOT?

If public opinion is influential, then why is Wang the only person within in ruling party that changed according to the shift of public opinion? The major reason has to do with Ma's tight control of the KMT. Despite earlier opposition, Ma won a reelection of the chairmanship in 2013, carrying 92 percent of votes and solidifying his power in the party. As the chairperson of the party, Ma wielded power to assign members to positions in local government and to recommend them for participation in legislative elections. As a result, KMT members would not want to oppose Ma for securing political benefits (Chung Reference Chung2013). Since Ma was still the chairperson of the KMT when the movement took place in 2014, it is logical that few members, if any, would come out and oppose his stance on the movement as they prepared for an upcoming legislative election at the end of 2014.

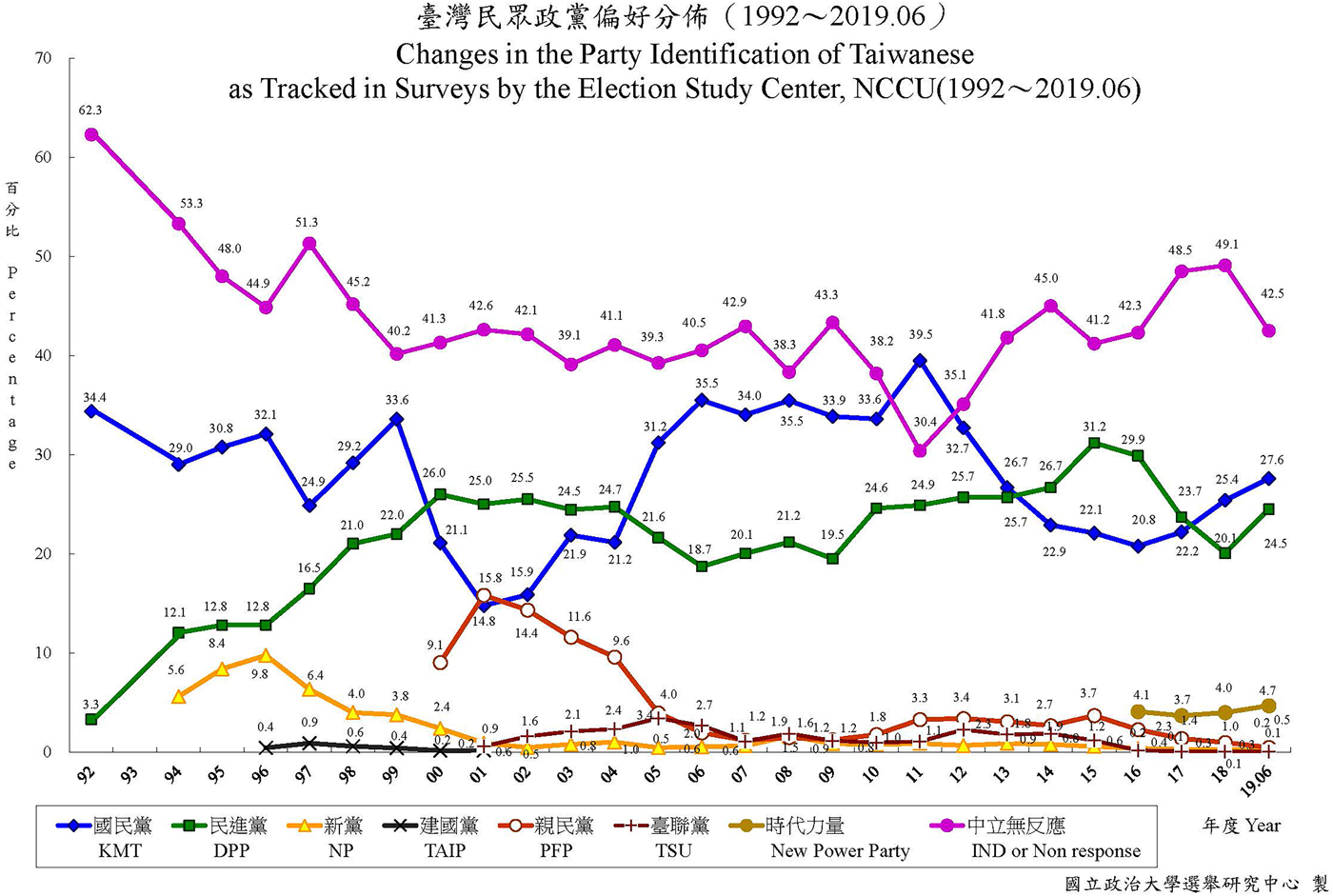

This then begs the question why Ma insisted on promoting the unpopular free-trade agreement in 2014 when his personal approval dropped precipitously. Figure 3 presents public support for different parties in Taiwan. In 2008, when Ma was first elected president, the KMT enjoyed a wide margin of nearly 15 percent over the DPP. However, after Ma came into the office, the margin gradually decreased. Before the movement occurred, support for the DPP had already passed that for the KMT.

Figure 3 Public Support for Political Parties in Taiwan

Ma's insistence on passing the trade pact has a lot to with his objective as a second-term president. Shortly after winning the reelection, Ma commented that achieving a historical legacy was his top priority and working toward a closer relationship with China was the core of his goal. Many China observers notes that Ma wanted the trade deal to pass because it would pave his way for a historical meeting with Xi Jinping (Banyan 2014; Matsuda Reference Matsuda2015). It is thus of little surprise that Ma remained intransigent in his opposition to the movement, as it thwarted his goal of achieving such a legacy. Ma's decision came with a political price. Support for the KMT took another hit, reaching its nadir in the past ten years in 2016, and ultimately the party lost the presidency to the DPP.

WHY PUBLIC OPINION WAS NOT RELATED TO THE ELITE RIVALRY

Critics of the public opinion hypothesis might argue that since the Ma–Wang rivalry existed before supportive public opinion emerged for the movement, public opinion could be attributed to the rivalry. There is little evidence to suggest that. Although the Ma–Wang rivalry started years before the protest, the rivalry did not influence public perception of the trade pact. If the rivalry had had any impact on the public view of the trade pact, then we should see that the public took a clear stance on it. However, a poll (TVBS 2014b) one year before the protest revealed that most citizens (85%) were unclear of the content of the trade pact and did not have a strong stance on it (32% support versus 43% oppose). Public lack of interest in the trade pact changed only after the movement began. Not only did the public show an increase in understanding of the trade pact, they also formed a clearer stance (TVBS 2014c). As a result, the protest outweighs the impact of the existing elite rivalry.

POLITICAL ALLIANCE WOULD NOT EXIST WITHOUT SUPPORTIVE PUBLIC OPINION

Lastly, a counterfactual might help us understand the importance of public opinion for Wang's political calculus. Let us imagine a scenario in which the Ma–Wang rivalry still exists, but public support for the occupation is low. Could Wang still support the movement? Unlikely. Supporting the movement would have had no political benefits for Wang. It would set him up against the public as well as against his peers inside his party, especially the president. Wang would end up finding his political power reduced. In fact, low support for the occupation did motivate Wang to end the movement.

This shows that supportive public opinion is the driver for political alliance, not Wang's rivalry with Ma. If the public did not support the movement, then Wang would not have supported it either, regardless of his personal rivalry with Ma. Throughout the movement, Wang operated from a position of paying close attention to public opinion before deciding his responses. Elite rivalry did exist, but it had little effect on his decisions.

IMPLICATIONS AND CONCLUSION

This article argues that public opinion, rather than elite rivalry, is the driving mechanism for the emergence of public alliance between political elites and the Sunflower movement. My interviews with elites and activists in Taiwan confirm the critical role of public opinion in influencing decision-making. Public opinion provides elites with information about the preferences of the public to reduce potential negative repercussions of decisions. Throughout the movement, Wang adapted strategically to the ebbs and flows of public opinion on the occupation of the legislature. On the contrary, elite rivalry is not as important as previously thought, due to 1) the unpredictably of social movement outcome, and 2) the risks of alienating his peers inside the party.

This case makes several contributions. First, it adds to the literature that argues that public opinion helps drive policy change (e.g. Agnone Reference Agnone2007; Soroka and Wlezien Reference Soroka and Wlezien2010; Dür and Mateo Reference Dür and Mateo2014). More importantly, the article reveals the mechanism through which public opinion influences public policy: by shaping elite decision-making and forming alliances with social activists. Additionally, this study makes the point that when social movements studies do not take public opinion into account, they may misattribute the underlying cause of a movement's success. In the case of the Sunflower movement, neglecting public opinion incorrectly amplified the effect of elite rivalry as the source of elite alliance. As a result, this article echoes efforts to broaden the theoretical framework of political opportunity structure to understand social movement (Manza and Brooks Reference Manza and Brooks2012).

Despite the findings, several caveats should be noted when thinking about generalizing the role of public opinion in other social movements. First, the tactic of the movement to occupy the legislature is not common in protest. The occupation of the legislature can be categorized as disruptive, and studies show that disruptive tactics often correlate with movement success (Cress and Snow Reference Cress and Snow2000). But such tactics can also hurt a movement's chance of succeeding, as they invite the government to respond harshly (Schumaker Reference Schumaker1978).

Secondly, the issue the Sunflower movement focused on was salient. Many social movements focusing on other topics, such as environmental preservation, renewable energy, or wages for factory workers, receive much less attention. The salience adds to the momentum of the movement. Lastly, the low popularity of the ex-president in Taiwan adds to the advantage of the movement. If the president had been more popular and had had greater control of the legislative body, then the movement would have been less likely to succeed.

Despite these boundary conditions, evidence that public opinion can help social activists by building an elite alliance has begun to emerge. For example, Dür and Mateo (Reference Dür and Mateo2014) find that a small group of citizens successfully blocked the verification of the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA) pact in Europe. Like those in the Sunflower movement, the activists had few resources, and their success is attributed to the high salience of the topic and supportive public opinion. The similar characteristics between this case and the Sunflower movement increase our confidence on the generalizability of findings.

One implication of the case of the Sunflower movement for social activists is that public opinion is a double-edged sword. Supportive public opinion help prolonged the Sunflower movement and offered political leverage to activists that they otherwise would not have. However, when the public's enthusiasm wore out, activists now found it difficult to continue their protest, as the lack of public interest would have given the elites a reason to bring an end to the protest. In this case, declining public support coincided with a political context that offered a solution in the movement's favor.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS

Charles K.S. Wu declares none. The author discloses receipt of the following financial support for research and fieldwork for this article: This work was supported by the Diversity and Inclusion Grant at Purdue University.

APPENDIX

Interview List