Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases are the number one cause of death globally. 1 Although these diseases manifest in adulthood, there is a large body of evidence to suggest that these diseases originate in early life.Reference Berenson 2 – Reference Raitakari, Juonala and Ronnemaa 4 It is thought that adaptations of the developing fetus to its environment may increase susceptibility to disease in later life.Reference Barker 5 – Reference Gluckman and Hanson 8 Maternal lifestyle preceding and during pregnancy is an important contributor to early-life programming of the offspring. Inadequate maternal nutrition during pregnancy increases the risks of cardiovascular diseases.Reference Roseboom, van der Meulen and Ravelli 9 , Reference Huang, Li, Wang and Martorell 10 Several studies have shown that the balance of macronutrients in the maternal diet during pregnancy is associated with offspring’s blood pressure decades later.Reference Roseboom, van der Meulen and Ravelli 9 , Reference Shiell, Campbell-Brown and Haselden 11 , Reference Campbell, Hall and Barker 12

Additionally, maternal exercise seems protective against the development of cardiovascular diseases in the offspring. Offspring of exercising pregnant women appear to have a lower resting heart rate, higher heart rate variability and improved vascular health.Reference Blaize, Pearson and Newcomer 13 However, there is a lack of knowledge regarding the type and amount of exercise needed to favourably program cardiovascular health of the offspring.

Although many studies examined the association between maternal dietary intake and physical activity in pregnancy and cardiovascular health of the offspring, the evidence has not been reviewed systematically. Therefore, we systematically reviewed all currently available evidence on the association of dietary intake and physical activity of women before and during pregnancy with offspring’s blood pressure and vascular health. Secondary objectives were to study the potential modifying role of period of gestation, offspring’s sex and pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) of the mother.

Methods

This systematic review was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. The review protocol was registered in the prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO; systematic review record CRD42015020244). The PICOS criteria, used to define the research question and to select the studies, are presented in Table 1. This paper is part of a broader systematic review project regarding the association between maternal lifestyle before and during pregnancy and offspring’s cardiometabolic health. In the current paper, we focussed on the cardiovascular outcomes as described in the outcome section of Table 1. A future paper will focus on the anthropometric and metabolic outcomes.

Table 1 Description of the PICOS criteria used for the selection of studies

Data sources and search strategy

A clinical librarian (J.L.) performed a systematic search in OVID MEDLINE (including Epub ahead of print, in-process and other non-indexed citations) and OVID EMBASE from inception to June 30, 2017 to identify observational and experimental human studies on (pre)pregnancy maternal diet and physical activity and cardiometabolic health in the offspring. We searched for the concepts ‘maternal’, ‘dietary intake’ or ‘physical activity’, ‘(pre-)pregnancy’ and ‘offspring/child’, using a wide variety of controlled terms, including MESH and text words. We did not search for specific outcomes as this would increase the risk of missing studies, but combined the search with a broad search filter for observational and experimental human studies. In addition, we applied a systematic review filter to check the existence of systematic reviews. No date or language restrictions were applied. We cross-checked the reference lists and the citing articles of the identified relevant papers in Web of Science and adapted the search in case of additional relevant studies. The bibliographic records retrieved were imported and de-duplicated in ENDNOTE. The complete search strategies are presented in Supplementary Table S1.

Study selection

The studies were independently screened by two reviewers (T.v.E. and M.K.) using the online screening and data extraction tool Covidence (www.covidence.org). Studies were eligible for full-text screening if they met the inclusion criteria as described in Table 1. Full-text articles were independently read by the same reviewers (T.v.E. and M.K.) and inter-reviewer discrepancies were resolved by discussion with a third person (M.v.P., A.G. or R.G.).

Data extraction and quality assessment

The categories used for data extraction can be found in Supplementary Table S2. Data were initially extracted by the first reviewer (T.v.E.), subsequently the second reviewer (M.K.) independently extracted data for 20% of the included articles (n=10 out of 48 articles; inter-reviewer discrepancy rate=3.98%).

The quality of the included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) was assessed using the Cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias. 14 For observational studies the quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) was used. 15 , 16 Because of the lack of a scoring system, we did not include the quality rating of this tool in our quality assessment. The quality check was conducted by the first reviewer (Tv.E.), subsequently the second reviewer (M.K.) independently checked 20% of all included studies (n=10 out of 48 articles: 8 out of 42 longitudinal studies and 2 out of 6 RCTs; inter-reviewer discrepancy rate=5.69%). Because of the low inter-reviewer discrepancy and the expectation that the errors were not systematic and without influence on either the data extraction or the quality assessment, a duplicate percentage of 20% was considered sufficient.

Data analysis

Results were presented per cardiovascular outcome [blood pressure combined with heart rate, and vascular health which comprised intima-media thickness (IMT) and pulse wave velocity (PWV)] and were grouped per child development stage. Observed associations were subdivided into positive associations: the higher the maternal diet/physical activity exposure, the higher the offspring health outcome (▲); negative associations: the higher the maternal diet/physical activity exposure, the lower the offspring health outcome (▼); no association (▬) or other associations (as specified). When maternal exposure was reported continuously as well as categorically, we included the results from the continuous exposure assessment. We did not include results of substitution models when used additionally to study associations of maternal diet with offspring health. When multiple adjusted models were shown, we included results of the fully adjusted model. The full data extraction table is included as a supplement.

Results

Selection of articles and study characteristics

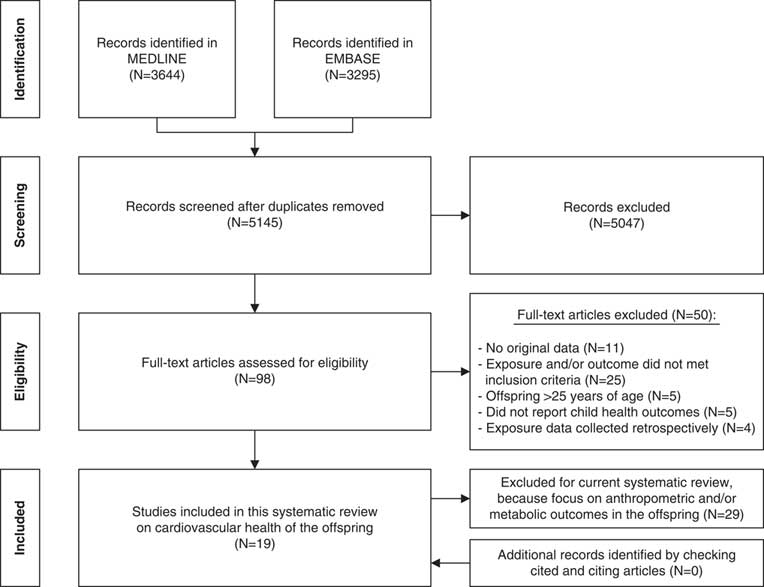

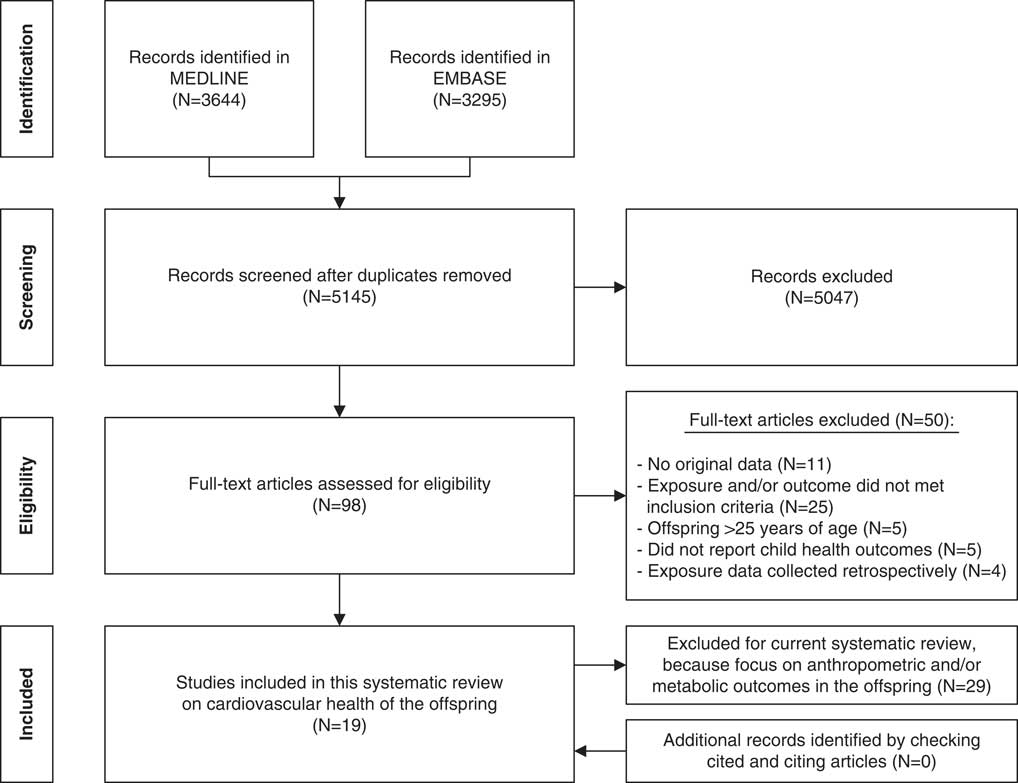

Of the 5145 articles retrieved and screened, 19 articles were judged to be eligible for inclusion in this systematic review. Reference checking of the cited and citing articles of the included articles yielded no additional relevant articles (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 PRISMA flowchart of the literature search.

The studies included in this review comprised three articles about intervention studies,Reference Aaltonen, Ojala and Laitinen 17 – Reference Normia, Laitinen and Isolauri 19 of which two articles used data from the same RCT and 16 articles about observational studies,Reference Adair, Kuzawa and Borja 20 – Reference van den Hil, Rob Taal and de Jonge 35 covering 12 mother–child cohorts (Table 2). During the offspring follow-up, one of the intervention studies did not examine their data as intervention v. control group but combined both groups.Reference Aaltonen, Ojala and Laitinen 17 There were 16 articles reporting on the association of maternal diet during pregnancy with offspring’s cardiovascular healthReference Aaltonen, Ojala and Laitinen 17 – Reference Chatzi, Rifas-Shiman and Georgiou 23 , Reference Gale, Jiang and Robinson 25 – Reference Leermakers, Tielemans and van den Broek 30 , Reference Rerkasem, Wongthanee and Rerkasem 33 – Reference van den Hil, Rob Taal and de Jonge 35 and three articles reporting on the association of maternal physical activity during pregnancy with offspring’s cardiovascular health.Reference Danielsen, Granström and Rytter 24 , Reference May, Scholtz, Suminski and Gustafson 31 , Reference Millard, Lawlor, Fraser and Howe 32 No studies included both maternal diet and physical activity in one paper, although the association with both maternal exposures was studied in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) cohort at the same child age.Reference Leary, Brion, Lawlor, Smith and Ness 29 , Reference Millard, Lawlor, Fraser and Howe 32 In addition, there were no studies examining maternal lifestyle before conception. Three mother–child studies examined offspring health twice over time and published the results in separate articles.Reference Aaltonen, Ojala and Laitinen 17 , Reference Normia, Laitinen and Isolauri 19 , Reference Chatzi, Rifas-Shiman and Georgiou 23 , Reference Huh, Rifas-Shiman and Kleinman 27 – Reference Leary, Brion, Lawlor, Smith and Ness 29 , Reference Millard, Lawlor, Fraser and Howe 32 However, studying similar maternal exposures and offspring health outcomes at both points in time was only done in the Nutrition, Allergy, Mucosal Immunology and Intestinal Microbiota (NAMI) RCT.Reference Aaltonen, Ojala and Laitinen 17 , Reference Normia, Laitinen and Isolauri 19 In all included articles, maternal diet and physical activity were measured using self-reported questionnaires or interviews. Offspring health outcomes were all measured during clinical examination, according to standardized study protocols.

Table 2 Characteristics, maternal exposure variables and offspring health outcomes of the included studies

N.S., not specified; RCT, randomized controlled trial; IMT, intima media thickness; FFQ, food frequency questionnaire; PUFA, poly-unsaturated fatty acids

a N from baseline table.

b Reference period of exposure assessment.

Blood pressure and heart rate

In total, 16 articles described the association of maternal lifestyle with offspring blood pressureReference Aaltonen, Ojala and Laitinen 17 , Reference Normia, Laitinen and Isolauri 19 – Reference Danielsen, Granström and Rytter 24 , Reference Hrolfsdottir, Halldorsson and Rytter 26 – Reference Leermakers, Tielemans and van den Broek 30 , Reference Millard, Lawlor, Fraser and Howe 32 – Reference van den Hil, Rob Taal and de Jonge 35 and three articles described the association of maternal lifestyle with offspring heart rateReference Bryant, Hanson and Peebles 22 , Reference May, Scholtz, Suminski and Gustafson 31 , Reference Rytter, Bech and Halldorsson 34 (Table 3; Supplementary Table S2). Maternal carbohydrate intake during pregnancy was studied in five articles. Its association with infant blood pressure was U-shaped,Reference Aaltonen, Ojala and Laitinen 17 while it was positively linearly associated to systolic blood pressure in pre-schoolReference Normia, Laitinen and Isolauri 19 and school-aged offspring.Reference Leary, Ness and Emmett 28 These linear associations were not observed for diastolic blood pressure.Reference Normia, Laitinen and Isolauri 19 , Reference Leary, Ness and Emmett 28 , Reference van den Hil, Rob Taal and de Jonge 35 No associations of maternal carbohydrate intake with blood pressure were observed in older offspring.Reference Leary, Brion, Lawlor, Smith and Ness 29

Table 3 Overview of the reported associations of diet and physical activity during pregnancy with offspring blood pressure and heart rate

▲, The higher the maternal diet/physical activity exposure, the higher the offspring health outcome; ▼, the higher the maternal diet/physical activity exposure, the lower the offspring health outcome; −, there is no effect observed of maternal diet/physical activity exposure with infant health outcome.

SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; MUFA, mono-unsaturated fatty acids; n − 6, omega-6 fatty acids; PUFA, poly-unsaturated fatty acids; HR, heart rate; SSDN, standard deviation of normal-to-normal inter-beat intervals; RMSSD, root mean square successive difference; LF, low frequency; HF, high frequency; ♂♀, results were stratified for male (♂) and female (♀) offspring.

Maternal fatty acid intake was studied in eight articles and was examined as total fat intake and/or as intake of different specific fatty acids during pregnancy. Maternal mono-unsaturated fat intake during pregnancy had an U-shaped association to infant diastolic blood pressure.Reference Aaltonen, Ojala and Laitinen 17 Maternal omega-6 and total poly-unsaturated fat intake were positively linearly associated to systolic blood pressure in pre-school-aged children.Reference Blumfield, Nowson and Hure 21 In addition, systolic blood pressure was lowest in offspring of mothers with a fat intake closest to the recommended intake (second tertile v. first tertile of intake).Reference Normia, Laitinen and Isolauri 19 These associations were not observed for diastolic blood pressure.Reference Normia, Laitinen and Isolauri 19 , Reference Blumfield, Nowson and Hure 21 Five articles reported no association of maternal fat intake during pregnancy with blood pressure in older offspring (total fat intake during pregnancy,Reference Adair, Kuzawa and Borja 20 , Reference Leary, Ness and Emmett 28 , Reference Leary, Brion, Lawlor, Smith and Ness 29 , Reference van den Hil, Rob Taal and de Jonge 35 saturated and unsaturated fatty acidsReference Leary, Ness and Emmett 28 and marine n − 3 fatty acidsReference Rytter, Bech and Halldorsson 34 ). However, Adair et al. Reference Adair, Kuzawa and Borja 20 observed a negative linear association of total fat intake with both systolic and diastolic blood pressure in adolescent girls.

Eight articles reported no association of maternal protein intake with offspring blood pressure.Reference Aaltonen, Ojala and Laitinen 17 , Reference Normia, Laitinen and Isolauri 19 – Reference Blumfield, Nowson and Hure 21 , Reference Huh, Rifas-Shiman and Kleinman 27 – Reference Leary, Brion, Lawlor, Smith and Ness 29 , Reference van den Hil, Rob Taal and de Jonge 35 Hrolfsdottir et al. Reference Hrolfsdottir, Halldorsson and Rytter 26 reported a positive linear association of maternal protein intake and offspring diastolic blood pressure in young adults. In contrast, Rerkasem et al. Reference Rerkasem, Wongthanee and Rerkasem 33 observed a negative linear association of maternal protein intake with offspring diastolic blood pressure. These associations were not observed for systolic blood pressure.Reference Hrolfsdottir, Halldorsson and Rytter 26 , Reference Rerkasem, Wongthanee and Rerkasem 33

Associations of maternal energy intake,Reference Aaltonen, Ojala and Laitinen 17 , Reference Adair, Kuzawa and Borja 20 , Reference van den Hil, Rob Taal and de Jonge 35 protein/carbohydrate ratio (P:C ratio)Reference Blumfield, Nowson and Hure 21 , Reference Leary, Ness and Emmett 28 , Reference van den Hil, Rob Taal and de Jonge 35 and fibre intakeReference Aaltonen, Ojala and Laitinen 17 , Reference Blumfield, Nowson and Hure 21 during pregnancy with offspring blood pressure were only reported in two or three articles with contrasting results. Maternal intake of specific foodsReference Aaltonen, Ojala and Laitinen 17 , Reference Bryant, Hanson and Peebles 22 , Reference Hrolfsdottir, Halldorsson and Rytter 26 , Reference Leary, Ness and Emmett 28 and dietary patterns during pregnancy,Reference Chatzi, Rifas-Shiman and Georgiou 23 , Reference Leermakers, Tielemans and van den Broek 30 as well as maternal physical activity during pregnancyReference Danielsen, Granström and Rytter 24 , Reference Millard, Lawlor, Fraser and Howe 32 in association with offspring blood pressure, were rarely studied. Furthermore, associations with offspring heart rate were rarely studied.Reference Bryant, Hanson and Peebles 22 , Reference May, Scholtz, Suminski and Gustafson 31 , Reference Rytter, Bech and Halldorsson 34

Vascular health

In total, five articles described the association of maternal lifestyle with offspring vascular healthReference Kizirian, Kong and Muirhead 18 , Reference Bryant, Hanson and Peebles 22 , Reference Gale, Jiang and Robinson 25 , Reference Leermakers, Tielemans and van den Broek 30 , Reference Rerkasem, Wongthanee and Rerkasem 33 (Table 4; Supplementary Table S2). PWV as well as IMT were studied in the carotid or in the aortic artery (descending thoracic aorta or proximal abdominal aorta). Two articles reported that maternal protein intake during pregnancy was negatively linearly associated to carotid IMT in school-aged offspringReference Gale, Jiang and Robinson 25 and in young adults.Reference Rerkasem, Wongthanee and Rerkasem 33 The association of maternal carbohydrate intake with offspring IMT was assessed inconsistently: maternal exposure was defined as glycaemic index or total carbohydrate intake, and vascular health measurements were done in the aortic or carotid artery.Reference Kizirian, Kong and Muirhead 18 , Reference Gale, Jiang and Robinson 25 , Reference Rerkasem, Wongthanee and Rerkasem 33 The association of maternal energy intake during pregnancy with offspring carotid IMT was only reported once.Reference Gale, Jiang and Robinson 25 Maternal fat intake and its association with offspring carotid IMT was reported in two articles with contrasting results.Reference Gale, Jiang and Robinson 25 , Reference Rerkasem, Wongthanee and Rerkasem 33 Maternal intake of specific foodsReference Bryant, Hanson and Peebles 22 and dietary patternsReference Kizirian, Kong and Muirhead 18 , Reference Leermakers, Tielemans and van den Broek 30 were rarely studied in association to offspring vascular health. There were no articles describing the association of maternal physical activity with offspring vascular health.

Table 4 Overview of the reported associations of diet and physical activity before or during pregnancy with offspring’s vascular health

▲, The higher the maternal diet/physical activity exposure, the higher the offspring health outcome; ▼, the higher the maternal diet/physical activity exposure, the lower the offspring health outcome; ▬, there is no effect observed of maternal diet/physical activity exposure with infant health outcome.

GI, glycaemic index; HF, high fibre.

Secondary research questions

We additionally focussed on the period of gestation, offspring’s sex, and obese v. normal weight mothers. In total, eight articles examined maternal lifestyle multiple times during pregnancyReference Aaltonen, Ojala and Laitinen 17 – Reference Normia, Laitinen and Isolauri 19 , Reference Blumfield, Nowson and Hure 21 , Reference Bryant, Hanson and Peebles 22 , Reference Gale, Jiang and Robinson 25 , Reference Huh, Rifas-Shiman and Kleinman 27 , Reference Rerkasem, Wongthanee and Rerkasem 33 (Table 2). Of those articles, four reported their results stratified for pregnancy periodReference Bryant, Hanson and Peebles 22 , Reference Gale, Jiang and Robinson 25 , Reference Huh, Rifas-Shiman and Kleinman 27 , Reference Rerkasem, Wongthanee and Rerkasem 33 with mixed results: Two articlesReference Bryant, Hanson and Peebles 22 , Reference Huh, Rifas-Shiman and Kleinman 27 did not observe differences in associations stratified for pregnancy period for offspring blood pressure outcomes. However, two other articles only observed associations of maternal carbohydrate intake in late pregnancyReference Gale, Jiang and Robinson 25 and of maternal protein intake in the first trimester of pregnancyReference Rerkasem, Wongthanee and Rerkasem 33 with offspring carotid IMT.

Two articlesReference Adair, Kuzawa and Borja 20 , Reference Danielsen, Granström and Rytter 24 stratified their results by sex (Table 3). Adair et al. Reference Adair, Kuzawa and Borja 20 only observed a negative linear association of maternal total fat intake with blood pressure in females. Danielsen et al. Reference Danielsen, Granström and Rytter 24 only observed a positive linear association of maternal daily amount of walking and bike riding with systolic blood pressure in males. In total, three articles did not take offspring’s sex into account in their final analysis.Reference Aaltonen, Ojala and Laitinen 17 , Reference Normia, Laitinen and Isolauri 19 , Reference May, Scholtz, Suminski and Gustafson 31

Two articlesReference Chatzi, Rifas-Shiman and Georgiou 23 , Reference Leermakers, Tielemans and van den Broek 30 added maternal pre-pregnancy BMI as an interaction term into their models, but in both studies it was a no-effect modifier. Seven articles did not take maternal (pre-pregnancy) BMI into account in their final modelReference Aaltonen, Ojala and Laitinen 17 , Reference Normia, Laitinen and Isolauri 19 – Reference Blumfield, Nowson and Hure 21 , Reference Huh, Rifas-Shiman and Kleinman 27 , Reference May, Scholtz, Suminski and Gustafson 31 , Reference Rerkasem, Wongthanee and Rerkasem 33 (Supplementary Table S2).

Quality of the included studies

The included RCTs scored generally low in the risk of bias assessment (Table 5). However, performance bias was present. For the observational studies, all articles clearly reported the objective and recruited study participants from the same population applying clear inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 6). Different levels of exposure were studied in association to the outcome, with exception of May et al. Reference May, Scholtz, Suminski and Gustafson 31 who used the level of exposure to define two groups for analysis. Most studies used self-reported questionnaires to determine maternal exposure, which were not always validated for the particular exposure of interest, nor a pregnant study population. All outcome assessments in the offspring were rated at low risk of bias, with exception of those in the article by Blumfield et al. Reference Blumfield, Nowson and Hure 21 who measured blood pressure only once per study visit.Reference Hure, Collins, Giles, Wright and Smith 36 The follow-up rate of 80% was most often not reached, with exception of the follow-up rate in the article by May et al. Reference May, Scholtz, Suminski and Gustafson 31 who measured the offspring at 1 month of age. The majority of studies did not correct for key potential confounding variables such as breastfeeding, maternal smoking, maternal age, maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and birth weight, with exception of Chatzi et al.Reference Chatzi, Rifas-Shiman and Georgiou 23 None of the studies gave a sample size justification. Because of the low number of RCTs and the heterogeneity in exposures, we were not able to conclude if RCTs showed different results compared with observational studies.

Table 5 Quality assessment of the included randomized controlled trial studies according to the Cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of biasFootnote a

a +=low risk of bias; −=risk of bias; ?=unclear.

b +/- for performance bias was given, because all three studies had a partly blinded design (two groups double-blind, one group single-blind).

c Blinding of the participants and personnel was not possible due to the nature of the intervention.

Table 6 Quality assessment of the included longitudinal studies according to the quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies of the NIHFootnote a

a CD, cannot determine; NA, not applicable; NR, not reported.

b Question 1. Was the research question or objective in this paper clearly stated?; Question 2. Was the study population clearly specified and defined?; Question 3. Was the participation rate of eligible persons at least 50%?; Question 4. Were all the subjects selected or recruited from the same or similar populations (including the same time period)? Were inclusion and exclusion criteria for being in the study pre-specified and applied uniformly to all participants?; Question 5. Was a sample size justification, power description or variance and effect estimates provided?; Question 6. For the analyses in this paper, were the exposure(s) of interest measured before the outcome(s) being measured?; Question 7. Was the timeframe sufficient so that one could reasonably expect to see an association between exposure and outcome if it existed? This question has been answered with ‘Not applicable’ for all studies, as we were interested in outcomes that may be considered proxies for cardiovascular disease risk instead of the so-called ‘hard outcomes’ as cardiovascular disease itself; Question 8. For exposures that can vary in amount or level, did the study examine different levels of the exposure as related to the outcome (e.g., categories of exposure, or exposure measured as continuous variable)?; Question 9. Were the exposure measures (independent variables) clearly defined, valid, reliable and implemented consistently across all study participants?; Question 10. Was the exposure(s) assessed more than once over time? Question 11. Were the outcome measures (dependent variables) clearly defined, valid, reliable and implemented consistently across all study participants?; Question 12. Were the outcome assessors blinded to the exposure status of participants?; Question 13. Was loss to follow-up after baseline 20% or less?; Question 14. Were key potential confounding variables measured and adjusted statistically for their impact on the relationship between exposure(s) and outcome(s), which were considered breastfeeding, maternal smoking, maternal age, maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and birth weight.

c Assessed for both included cohorts independently

d According to study protocol, blood pressure was only measured 1 time unless the outcome exceeded the reference values.

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first systematic review on the association of dietary intake and physical activity of pregnant women with offspring’s cardiovascular health, including both observational and experimental human studies. In total, we included 19 studies with over 29,000 participants. High maternal carbohydrate intake in pregnancy was consistently associated with higher blood pressure of the offspring. Less consistent associations were observed for high maternal intake of unsaturated fatty acids and low total fat intake with higher offspring blood pressure. There was no evidence for a programming effect of maternal protein intake on offspring blood pressure. Maternal protein intake during pregnancy was negatively associated to carotid IMT in school-aged and young adult offspring. We were unable to assess the potential modifying role of period of gestation, offspring’s sex or BMI of the mother, because of the small number of studies reporting stratified results.

Underlying mechanism

We speculate, in line with the results of previous studies,Reference Shiell, Campbell-Brown and Haselden 11 , Reference Campbell, Hall and Barker 12 , Reference Roseboom, van der Meulen and van Montfrans 37 that the observed associations between offspring blood pressure with maternal carbohydrate intake can be explained by the ratio between maternal protein to carbohydrate intake (P:C ratio). Maternal energy and protein needs increase during pregnancy, which enables the fetus and placenta to grow.Reference Duggleby and Jackson 38 A low intake of maternal protein and an increased intake of carbohydrates are associated with reduced placental weight.Reference Campbell, Hall and Barker 12 , Reference Godfrey, Robinson, Barker, Osmond and Cox 39 Reduced placental size might induce increased placental flow with lasting consequences for the pressure against which the fetal heart develops.Reference Thornburg, O’Tierney and Louey 40 Such increased levels of pressure may have lasting effects for the physiology of heart and blood vessels and might increase later blood pressure. Indeed, there is evidence that reduced placental size is linked to increased risks of hypertension in later life.Reference Barker, Thornburg, Osmond, Kajantie and Eriksson 41

This also explain the observed association of a lower maternal protein intake with a higher offspring’s carotid IMT. But lower overall maternal energy intake altering endothelium-dependent responses in the offspring’s aortaReference Franco, Arruda and Dantas 42 could also explain this association, as there is evidence for a negative linear association of adequate maternal energy intake with carotid IMT in school-aged offspring.Reference Gale, Jiang and Robinson 25

We observed weak evidence for a programming effect of maternal fat intake with offspring blood pressure.Reference Aaltonen, Ojala and Laitinen 17 , Reference Normia, Laitinen and Isolauri 19 – Reference Blumfield, Nowson and Hure 21 This is in line with evidence from animal studies, showing that high fat diets before and during pregnancy induced high blood pressure through endothelial dysfunction, including reduced endothelium-dependent vasodilatation in both small and large vessels and increased aortic stiffness.Reference Drake and Reynolds 43

Interpretation of the results

Most of the included studies assumed a linear association of maternal lifestyle with offspring cardiovascular health, or did not report whether assumptions for linearity were justified. U-shaped or trends towards (reversed) U-shaped relationships were also observed.Reference Aaltonen, Ojala and Laitinen 17 It could be that associations went undetected by using inappropriate statistical models.

Associations may also have gone undetected since most studies failed to report stratified analyses for sex. There is evidence for sex differences in the programming of cardiovascular diseasesReference Adair, Kuzawa and Borja 20 , Reference Danielsen, Granström and Rytter 24 and although the underlying mechanism is unclear, it seems that male offspring are more sensitive to their prenatal environment.Reference Dasinger and Alexander 44 – Reference Ojeda, Intapad and Alexander 46 For example, intrauterine growth restriction caused by placental insufficiency resulted in a significant increase in blood pressure in young adulthood in male offspring, whereas female offspring were normotensive.Reference Dasinger and Alexander 44 , Reference Alexander 47

Questionnaires used to measure maternal exposure were not always validated for the particular exposure of interest, or they were not validated for use in a pregnant population. This makes it questionable whether the observed (non)associations are due to measurement error, and also therefore associations may have gone undetected. Additionally, the majority of the included observational studies did not correct for key potential confounders such as breastfeeding, maternal smoking, maternal age, maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and birth weight. Therefore, residual confounding could have influenced the results and made results less reliable.

In view of the overwhelming amount of evidence, we a priori decided to study the programming effects of maternal diet and physical activity in pregnancy and offspring’s cardiovascular health up to the age of 25 years. Nevertheless, there is evidence that the associations between maternal diet and offspring blood pressure persist into adulthood and may increase over time.Reference Roseboom, van der Meulen and Ravelli 9 , Reference Shiell, Campbell-Brown and Haselden 11 , Reference Campbell, Hall and Barker 12

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this review is the systematic approach in finding and summarizing the available evidence on the association of maternal diet and physical activity with offspring cardiovascular health including both observational and experimental human studies. We were therefore able to give a comprehensive overview of the available literature. Owing to the heterogeneity in the assessment of maternal dietary intake and physical activity, the vascular outcomes, and the differences in offspring age, a meta-analysis was not possible. Associations of maternal lifestyle with offspring cardiovascular health were rarely studied using an RCT design. Therefore, we were not able to infer causality. There are, however, indications for causality from the UPBEAT trial, showing that a lifestyle intervention targeting maternal diet and physical activity during pregnancy had the potential to reduce infant adiposity.Reference Patel, Godfrey and Pasupathy 48 Also, animal studies convincingly show that maternal lifestyle in pregnancy causes lasting changes to the offspring cardiovascular system.Reference Blaize, Pearson and Newcomer 13 , Reference Harding 49 , Reference Chavatte-Palmer, Tarrade and Rousseau-Ralliard 50

Recommendations for further research

In order to optimally use the information from studies on maternal lifestyle and offspring health, harmonization of valid exposure and outcome measurements and the development of core outcome sets would reduce research waste and speed up scientific progress in this field.Reference Oliver Daly 51 , Reference Duffy, Rolph and Gale 52 Since there is evidence from animal studies that maternal exercise can abolish the negative effects of maternal diet,Reference Rosenfeld 53 more research should focus on the programming effect of maternal physical activity in combination with maternal diet, which both should be examined validly and consistently across studies. Moreover, studying both maternal diet and physical activity at the same time could give more insight in the role of maternal energy balance on offspring cardiovascular health, with the ultimate goal to gain knowledge on how to help women to provide their child with the best start in life through an optimal lifestyle before and during pregnancy. In order to establish causality, experimental studies of lifestyle interventions before and during pregnancy should include follow-up of the offspring.

Conclusion

Currently there is a lack of consistent evidence to be able to draw robust conclusions on the association of women’s dietary intake and physical activity before and during pregnancy with offspring’s blood pressure and vascular health. We did find evidence for an association of high maternal carbohydrate intake with higher offspring blood pressure, and a negative linear association of maternal protein intake with offspring carotid IMT. We hypothesize that the macronutrient composition of the diet underlies these associations. However, no consistent findings for maternal fatty acid intake were found. There were too few studies to draw conclusions on energy intake, fibre intake, P:C ratio, specific foods, dietary patterns and maternal physical activity. Harmonization of valid exposure and outcome measurements, and the development of core outcome sets are needed to enable more robust conclusions.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S204017441800082X

Acknowledgements

None

Financial Support

T.M. van Elten and M.D.A. Karsten are supported by grants from the Dutch Heart Foundation (2013T085) and the European Commission (Horizon2020 project 633595 DynaHealth). Neither the Dutch Heart Foundation nor the European Commission had a role in data collection, interpretation of data or writing the report.

Conflict of Interest

None