Introduction

Research suggests that institutions have a greater ability than individuals to challenge existing systemic barriers and create lasting changes to improve diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) [Reference Enders, Golembiewski, Orellana, Silvano, Sloan and Balls-Berry1], and that cultural change is critical to enhance recruitment and retention of diverse individuals [Reference Enders, Golembiewski, Pacheco-Spann, Allyse, Mielke and Balls-Berry2]. Evidence also shows that diversity within clinician and scientist teams is associated with better patient outcomes [Reference Nelson3] and greater academic impact (e.g., higher impact papers) of scientific findings [Reference AlShebli, Rahwan and Woon4]. Importantly, to achieve equity in healthcare and health research, we cannot rely on minority-serving institutions or historically minoritized individuals to carry the full burden because systemic problems require systemic solutions [Reference Clark and Hurd5,Reference Boulware, Corbie and Aguilar-Gaxiola6]. Instead, all institutions must work to achieve equity. In this paper, we present ideas for a comprehensive DEI Action Plan to assist academic medical and biomedical research institutions in initiating activities related to DEI.

Types of Diversity

To assess DEI efforts, it is critical to specify what we mean by “diversity.” Figure 1 lists diversity types that we feel should be included. Importantly, individuals may have multiple social identities or characteristics that intersect, which may increase their vulnerability to the intensity and impact of negative experiences, leading to diminished respect and protection for and belief in these individuals.

Fig. 1. Examples of visible and invisible diversity types common in academic and medical institutions. Note: The lists above are not exhaustive, and we acknowledge that other important types of diversity may be missing. In addition, while usual visibility or invisibility is shown here, there may be variation in visibility for individual cases.

DEI Action Plan Items

The thirteen items below represent a comprehensive and strategic plan for change at the institutional level. These concepts were initially developed for the Center for Leading Innovation and Collaboration’s “Cohorts for Change: Building Anti-Racism Initiatives within CTSA Hubs” 2021–2022 course offering (https://clic-ctsa.org/cohorts-for-change), the goal of which is to promote structural and administrative antiracism efforts at CTSA member organizations.

Diverse Representation across Levels

Investigate and quantify diversity among trainees and faculty, on promotion and search committees, and in leadership at the chair, director, dean, and C-suite levels. Ensure aggregate diversity data are reported in large enough categories as to avoid identifying individuals whose diversity may not be known within their work group. Avoid a single “minority” category for race and ethnicity, as members of different historically minoritized groups must contend with distinct stereotypes and prejudices [Reference Siy and Cheryan7]. Moreover, take note of the extent to which institutional diversity reflects – or does not reflect – the intended patient population and research participants served by the institution as well as its surrounding community.

Importantly, there is no magic diversity metric that will be the key to achieving feelings of inclusivity and belonging among diverse members of the institution. Instead, research suggests that institutions should strive to avoid the phenomenon of “only-ness” for members of diversity groups (e.g., only one woman or person of color on a committee) and continually review processes for recruiting, hiring, and promoting (see below points) [Reference Sneader and Yee8].

Assessment of Unconscious Bias

Nearly everyone carries unconscious bias [Reference Morin9], which – no matter how well-meaning the individual – can manifest in harmful microagressions or discrimination against diverse colleagues. Even when not intended, such sequelae may bear significant impact for diverse individuals, impacting the sense of belonging and over time the intent to remain in the position or institution. Awareness of one’s own unconscious bias is a necessary first step in mitigating its impact. For example, when all members of the Ohio State University College of Medicine admissions committee took the black-white Harvard Implicit Association Test (IAT), the subsequent year’s medical school class saw a 26% increase in underrepresented minority students who matriculated [Reference Capers, Clinchot, McDougle and Greenwald10]. Findings from this and other studies indicate that awareness alone of one’s implicit bias can translate into behavior change. Therefore, all individuals at the institution should be encouraged or even required to examine their own unconscious bias using the IAT (https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/takeatest.html). While the IAT is not perfect, it is the only objective measure of unconscious biases across a wide range of diversity subtypes.

Anonymous Survey

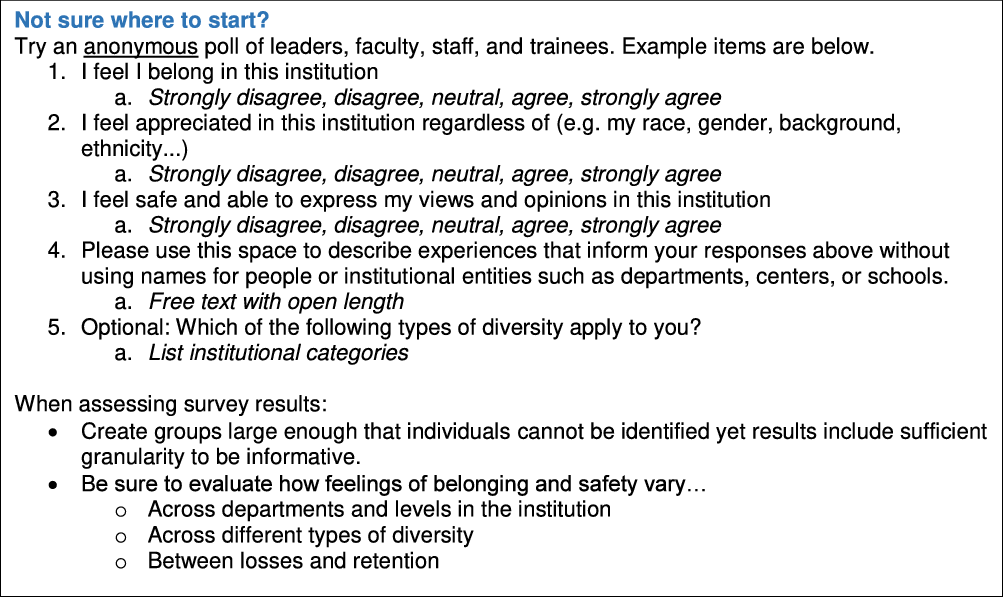

In keeping with the principles of “institutional courage” [Reference Freyd11], which advocates for systematic, anonymous collection, and transparent reporting of abuse within institutions, anonymously survey individuals at all levels of the institution regarding their sense of belonging and inclusion (Fig. 2). Compare responses across demographics, institutional groups, and hierarchical levels. As above, avoid grouping all minority groups together. Distinguish participants by visible and invisible diversity types to further assess responses. Include open-ended options for participants to clarify their responses and provide additional feedback on opportunities to enhance DEI.

Fig. 2. Sample survey items for anonymous polling of institutional members.

Assess Promotion Patterns

How do promotion patterns differ by diversity? This is a critical question to assess whether issues seen at the individual level are impacting the institution. Concerns may arise at three levels:

-

1. Departmental leaders may have unconscious or conscious biases. For instance, women but not men may be asked to prove readiness for promotion [Reference Williams and Dempsey12]. As such, departmental “gate-keepers” may hold individuals from certain groups back from submitting a promotion packet.

-

2. Appointment and promotion committee members may themselves be biased. Education can help with unconscious bias from gatekeepers and committee members [Reference Carnes, Devine and Isaac13]. Committee members should also be informed on the biases that can be found in peer review letters and given examples of problematic language.

-

3. External peer reviewers have been shown to often incorporate bias within letters [Reference Iezzoni14,Reference Hengel15].

Contribution to DEI in Appointments and Promotions

An individual’s contribution to DEI should be considered during appointments and promotions. Diversity statements, known more generally as contributions to DEI, are a powerful way to reward DEI efforts and partially account for the minority tax, in which diverse individuals spend more time mentoring and on committees due to the need for representation. However, contributions to DEI must be meaningfully scored and not merely symbolic [16–18]. A critical question to ask is Can an appointment or promotion advance without taking contributions to DEI into consideration? If the answer is yes, then the impact on DEI at the institution may not be as intended.

Contribution to DEI on Annual Reviews and Performance Assessments

Annual reviews should be formatted to explicitly include details on the individual’s DEI contribution. Figure 3 shows five broad areas in which individuals may have contributed to DEI; individuals should provide examples of their actions in applicable areas. Illustrative examples are included in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Example DEI contribution worksheet for annual review or performance appraisal.

Funding for Research

National research funding has never achieved equity for researchers from underrepresented backgrounds [Reference Taffe and Gilpin19]. Therefore, it is incumbent upon institutions to utilize national mechanisms to gain funding for diverse investigators. For example, a diversity supplement can be applied to many federal grant awards. However, the principal investigator (PI) may not know a suitable individual or know that an individual is diverse according to the NIH definition [20]. Institutions should systematically review eligible awards for inclusion of supplements and match PIs who lack a supplement with eligible candidates. Often diverse individuals are isolated within the institution, so grant writing assistance can be especially beneficial [Reference Arnold21].

Search Committees

Unconscious bias also impacts the recruitment and hiring process [Reference Corrice22]. Members of search committees for trainee positions, faculty appointments, and leadership positions should be required to undergo training to minimize bias [Reference Isaac, Lee and Carnes23]. In addition, each search committee should include a person designated to speak up regarding diversity and that individual should be a voting member of the search committee. In addition, to avoid the illusion that this person can or should speak for all types of diversity based solely on their own background, there should be additional training requirements so that person is aware of issues that span multiple groups. “Fit with the institution” should be carefully assessed for bias in favor of the majority cultural groups at the institution [Reference Gray24].

Retention

Gaps regarding access to research funding, mentorship, and academic promotion, and experiences of discrimination, among other factors, may contribute to attrition of diverse trainees, faculty, and staff from academic medicine [Reference Clark and Hurd5]. Experiences of discrimination can lead to burnout [Reference Hu, Ellis and Hewitt25] and adverse psychological, neural, and medical outcomes [Reference Williams, Lawrence, Davis and Vu26], suggesting that retention and professional success within this environment likely come at a high personal cost for diverse individuals[Reference Clark and Hurd5] Strategies for retention of diverse individuals must be intentional, including, but not limited to, effective mentorship, access to networking, opportunities for professional growth (e.g., continuing education), promotion of “work/life balance,” and a welcoming, inclusive institutional culture [Reference Musser27]. Although a human resources representative from the organization often conducts exit interviews, departing faculty or trainees may feel reluctant to share negative experiences openly and honestly. Alternatives include an ombudsperson or a representative from the institution’s office of faculty affairs and/or office for equity and diversity. The exit interviews can serve as a critical component of a “needs assessment” to identify and elucidate organizational, structural, or cultural factors that contributed to the individual’s departure [Reference Sengupta, Sengupta and Bandopadhyay28].

Mentoring

All trainees, faculty, and mentors should be required to participate in mentorship training and examine their own unconscious bias. Mentorship training should include issues that are specific for diverse mentees [Reference Enders, Golembiewski, Orellana, Silvano, Sloan and Balls-Berry1]. In particular, mentors should be reminded to serve as allies for diverse trainees and provide equitable sponsorship and networking opportunities for all trainees.

Supporting Trainees

Mentors and other faculty and staff should talk with all trainees to individually assess the impact of external barriers on their learning process. For instance, many graduate students and postdoctoral fellows face depression, anxiety, and food insecurity due to low stipends [Reference Bruening, Argo, Payne-Sturges and Laska29,Reference Forrester30]. In particular, stipend levels are not adjusted for cost-of-living or inflation. Stipend levels aggravate diversity issues, as candidates of lower socioeconomic levels may be unable to begin or continue their graduate work [Reference Patel31]. Other individual issues may include: distant housing and/or lack of reliable transportation; the need for the trainee to send money home to assist their families, which is true for many trainees from international backgrounds and/or lower socioeconomic groups; difficulty prepaying for required items such as travel or other purchases and then waiting for reimbursement; and lack of appropriate network capability or device for remote access to institutional tools.

Safe Reporting

Safe reporting is a challenge primarily because of retaliation, which may take many forms and be masked as an honest change in activity allocation. Most institutions provide avenues to report concerns anonymously. However, institutions should be aware that when an individual is the only person in their area with their diversity, traditional institutional paths may not provide protection against retaliation. Importantly, poor institutional handling of reports is a significant driver of underreporting of harassment, bullying, and other concerns in academic settings [Reference Bergman, Langhout, Palmieri, Cortina and Fitzgerald32]. Therefore, we also recommend that institutions develop uniform processes to assess possible retaliation after the conclusion of a reported incident. Ideally, a supportive institutional official will contact the person who made the report through an in-person meeting or via phone, since efforts to collect possible retaliation in written formats are far less likely to succeed. In any follow-up, it is vital that institutional officials give greater weight to the impact of potential retaliation than to the stated intent for the action. In addition to following up in individual cases, institutions should track observed or suspected retaliation over time so that patterns of repetition can be identified and addressed.

Institutional Standards

Comprehensively and annually review institutional standards for lack of diversity. For instance, review internal and external websites for inclusivity of photos and examples. Review application processes for excessive application fees and unnecessary standardized testing. Be transparent to all applicants about options for fee or testing waivers. Review dress codes for inclusivity of racial and ethnic individuals. Develop institutional tools for employees and patients to provide their pronouns and pronunciation of their names. Assess institutional feedback mechanisms to ensure supervisors who review feedback are trained in identifying cases in which feedback may serve as a tool for bullying a diverse person or providing feedback that is typically not given to majority individuals. Training for supervisors should include 1) when to consider excluding feedback and 2) when and how to approach an individual who provided inappropriate feedback. Train security and lobby staff to implement any security checks or procedures for medical staff in a consistent and unbiased way to avoid singling out or harassing employees who may not “look like” their idea of a medical or research professional. Establish expectations that all individuals should be treated with respect and that diverse employees and trainees should not be questioned any more than others.

Surrounding Area

Institutions must consider the surrounding community in order to maximize recruitment and retention of diverse individuals. Are neighborhoods segregated? What practices do realtors utilize, and how do these practices differ depending on a client’s background? Are schools in the area equally strong for different neighborhoods? How equitable are schools for trainees of different diversity types? Identify these concerns and brainstorm ways that your medical institution – which likely wields enormous financial and political clout locally – can work to be a driver of inclusion and equity in the area.

Conclusion

This list assembles concepts to help institutions identify mechanisms for enacting change and accelerating shifts in institutional culture. It is important to note that institutions should also increase diversity by hiring and admitting faculty, staff, and trainees from diverse and underrepresented backgrounds. We feel the concepts outlined in this action plan are complementary to increasing diversity targets by creating and sustaining environments that will attract diverse talent. Institutions who adopt these or similar action steps should also create an evaluation framework as a way to monitor implementation, track key outcome measures, and make process improvements where necessary. In order to carry out this work successfully, institutions need to allocate funding toward DEI efforts, including funding for leadership, staff, and the discretionary budget. In addition, DEI leadership must be integrated with institutional leadership teams to ensure bidirectional communication. We look forward to institutions bringing new and innovative tools to bear to shift the face of biomedical research to better reflect their communities, patients, and research participants.

Acknowledgments

This publication was supported in part by Grant Number UL1 TR002377 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS). This work was also funded in part by the University of Rochester Center for Leading Innovation and Collaboration (CLIC), under Grant U24TR002260. CLIC is the coordinating center for the Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) Program, funded by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This work is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.