Introduction

Community-engaged research (CEnR) is a widely adopted approach when addressing community-level health concerns, as it aims to partner with communities, build leadership, prevent exploitative research practices on vulnerable populations, and enhance the capacity for community participation in research [Reference Dozier, Hacker, Silberberg and Ziegahn1]. CEnR is defined as “the process of working collaboratively with and through groups of people affiliated by geographic proximity, special interest, or similar situations to address issues affecting the well-being of those people” (CDC, Principles of Community Engagement, 2005) [Reference Dozier, Hacker, Silberberg and Ziegahn1]. Understanding the social, environmental, and cultural context in which an individual lives is crucial for addressing how health issues are perceived and can be targeted. Documented examples of exploitative research practices on racial/ethnic and underserved communities have led to distrust of academic research [Reference Nunn2,Reference Scharff, Mathews, Jackson, Hoffsuemmer, Martin and Edwards3]. CEnR is a framework that attempts to undo the distrust of academic research through collaboration and engagement of community members as participants in research, rather than the subjects of research. The principles of CEnR are founded on establishing a mutual relationship between researchers and the community and recognizing the wealth of knowledge that community members possess. CEnR requires the establishment of trust, collaboration, and negotiation in order to identify and address health issues that affect the community.

This approach encompasses a spectrum of strategies and research methodologies in which researchers collaborate with community partners to identify health disparities that affect the community as well as the strengths, preferences, and priorities of community partners [Reference Balls-Berry and Acosta-Perez4,Reference Barkin, Schlundt and Smith5]. As the level of community engagement and involvement increases, so does the ability of communities to be equal representatives in the research process. For example, community-based participatory research (CBPR) is one such orientation that sits on one end of the spectrum of CEnR with the highest level of community involvement, in which there exists a strong bidirectional relationship between the community and researchers with the decision-making driven at the community level [Reference Dozier, Hacker, Silberberg and Ziegahn1]. This research orientation seeks to build trust and relationships with community partners to better meet the needs of the community and address health priorities and health disparities [Reference Coffman, de Hernandez and Smith6,Reference McElfish, Moore, Laelan and Ayers7]. CBPR has been a more widely adopted approach for improving public health outcomes [Reference Minkler, Blackwell, Thompson and Tamir8,Reference Cross, Pickering and Hickey9]. Studies have used the CBPR approach to identify health issues and address health outcomes such as chronic diseases, environmental health concerns, workplace health, and infectious disease prevention, and control [Reference Mohamed, Lantz and Ahmed10,Reference Campbell, Yan and Egede11].

Prior to beginning any investigative studies with human participants, research must be approved by a research ethics review committee, typically referred to as an Institutional Review Board (IRB) in the USA. IRBs are independent research ethics committees charged with the responsibility of protecting the rights, welfare, and well-being of human subjects involved in any research that involves human participants. There are independent and academic center-affiliated IRBs. Under the Office for Human Research Protections, an IRB is meant to uphold federal standards to prevent the exploitation of human participants in research. Upon review of any form of research involving human participants, the IRB has the authority to approve, modify, or disapprove the research proposal.

Though many goals of CEnR align with that of the IRB to protect human research subjects from unethical harm, researchers and community members conducting CEnR are often met with challenges when seeking to obtain research approval. Because CEnR research design greatly differs from traditional biomedical research methodology, IRB review and approval present unique challenges for CEnR researchers. Previous articles have explored and examined the experiences of community-engaged researchers with the IRB process [Reference Wolf12]. These studies have noted several challenges in working with IRBs to review and approve CEnR protocols. However, to our knowledge, there has been a lack of literature that examines these challenges, promising practices and lessons learned from CEnR researchers engaging with academic and affiliated IRBs, and recommendations for navigating the review process.

The aim of the scoping review is to identify challenges that researchers and community partners encounter as well as promising practices that researchers and community partners utilize when working with IRBs for study review of CEnR studies conducted in the USA. We hope that the identified challenges and lessons learned can guide recommendations to better facilitate the research approval process.

Method

Following the PRISMA guidelines for scoping reviews (PRISMA-Scr), a review was conducted for the available studies describing ways in which IRBs engage CEnR [Reference Tricco, Lillie and Zarin13]. In August 2019, a trained medical librarian (TR) performed searches for studies without language or date restrictions in MEDLINE, PsycInfo (using the Ovid Platform), and CINAHL (using the Ebsco Platform.) The Ovid Medline search strategy is available in the supplementary materials of this article.

Articles were included in the review if the study (1) reported on CEnR; (2) specified study-related challenges, barriers, lessons learned, or guidelines for working with an IRB; (3) published in a peer-reviewed journal; (4) conducted in the USA; and, (5) had the IRB located in the USA and connected to an academic institution.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses on related topics were excluded from the scoping review to avoid duplicate studies. However, individual studies listed in these excluded systematic reviews and meta-analyses were tagged for further review. CEnR study proposals by institutional, ethical, or community review boards that were not conducted in conjunction with an academic IRB were also excluded from this review. For this review, we sought to identify and document challenges and facilitators when seeking approval for CEnR from an IRB located at an academic institution.

The title and abstract screening were completed by a team of two co-authors (HT, JP) who identified studies that included academic researchers conducting a CEnR study. Additional criteria included articles that specified study challenges, barriers, lessons learned, promising practices, or facilitators for working with an IRB that was affiliated with an academic institution. These co-authors independently screened titles and abstracts based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria to determine inclusion status. Each citation received two votes from the co-authors and conflicts were solved through consensus or with a third co-author (DO). Two of the co-authors (DO, JP) then conducted a full-text review of the included abstracts to ensure that the articles aligned with the established inclusion and exclusion criteria. Those that did not fit the criteria were excluded. Data extraction was completed with the final set of articles. An extraction table template was designed to extract key barriers, facilitators, and recommendations from CEnR studies, study demographics, and study type. This template was designed using Covidence, this software ensured parsimony in the extraction process for each article. Reviewers independently extracted data and the software compared information extracted by each reviewer. Differences in extracted information for each article were discussed between reviewers and the information was consolidated and finalized into one data template.

The elements for extraction included the following: study aim and design, participant demographics, recruitment methods, sample size, description of community partnerships, types of CEnR conducted, types of review boards, challenges, lessons learned, and recommendations for engaging with IRBs and review board research outcomes (i.e. research approval or denial). This final set of articles were independently reviewed for data extraction by two authors (DO, JP). These authors convened to review and finalize the extracted data for analysis.

Results

In total, 1192 articles were identified from the database searches. After the removal of duplicates, 795 articles were screened by title and abstract, 705 articles were deemed irrelevant and 90 articles were selected for full-text assessment. Seventy-four articles were excluded using the following exclusion criteria: (1) The article was a literature review, commentary, or letter to the editor (n = 23); (2) The article did not specify barriers, facilitators, or recommendations for engaging with IRBs (n = 16); (3) The article did not report engagement with IRB (n = 12); (4) The article was not a CEnR study (n = 15); (5) The IRB was not affiliated with an academic institution (n = 6); and (6) The study was not conducted or reviewed in the USA (n = 3). Thus, 15 articles met the eligibility criteria and were extracted and included in this review (See Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases and registers only. From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/.

Study and Population Characteristics

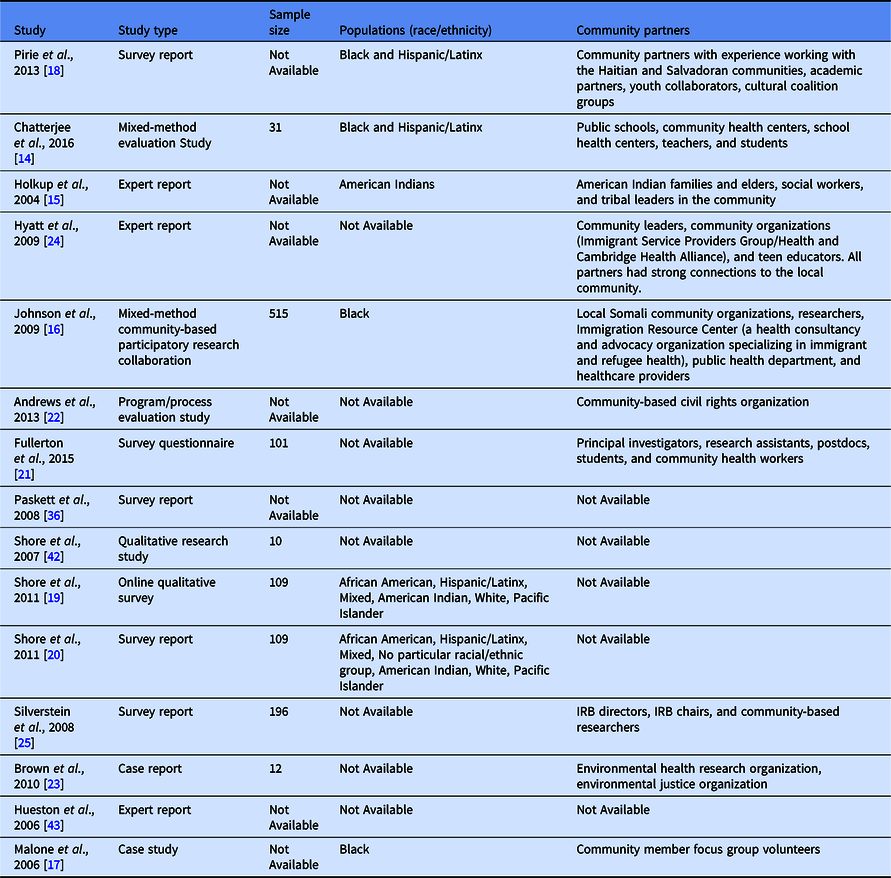

Most articles were published between 2004 and 2016. Studies were characterized as an evaluation study (n = 2), survey questionnaire/report (n = 6), qualitative focus group study (n = 1), case/expert report (n = 4), pre-post (n = 1), or mixed-method CBPR collaboration (n = 1). When specified, most studies sampled people from racial and ethnic groups (Black, Hispanic/Latinx, and American Indian) [Reference Chatterjee, Daftary, Gatison and Gillman14–Reference Shore, Drew, Brazauskas and Seifer20]. Sample sizes ranged from 10 to 900 depending on the study design. While age was not specified in most studies, most participants were adults with some studies engaging older adults 65+ [Reference Holkup, Tripp-Reimer, Salois and Weinert15–Reference Pirie and Gute18,Reference Fullerton, Anderson, Cowan, Malen and Brugge21] and teenage/young adults [Reference Chatterjee, Daftary, Gatison and Gillman14,Reference Pirie and Gute18]. When specified, community partners included public schools, immigration services, youth collaborators, non-profit organizations, health providers, American Indian organizations, and other racial and ethnic community social service organizations [Reference Chatterjee, Daftary, Gatison and Gillman14–Reference Pirie and Gute18,Reference Fullerton, Anderson, Cowan, Malen and Brugge21–Reference Silverstein, Banks, Fish and Bauchner25]. (See Table 1)

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of all study populations included in the scoping review

Additionally, Tables 2 and 3 detail each of the 15 studies included in this scoping review. They provide an overview of each of the study goals and discuss the challenges/barriers and lessons learned implemented in the studies as well as future recommendations for CEnR researchers to implement when they encounter similar challenges.

Table 2. Primary research studies documenting challenges and recommendations for engaging with IRBs

CBPR, community based participatory research; CEnR, community-engaged research; CTSI, Clinical and Translational Science Institute; IRB, Institutional review board

Table 3. CEnR investigator/expert reports documenting challenges and recommendations for engaging with IRBs

CBPR, community based participatory research; CEnR, community-engaged research; CTSI, Clinical and Translational Science Institute; IRB, Institutional review board

Challenges and Promising Practices for Engaging with IRBs

Challenge #1: Community partners not being recognized as equal research partners

One of the biggest challenges CEnR researchers reported was that IRBs often did not recognize community partners who are interested in engaging in human subjects research (HSR), as equal research partners/stakeholders in the process of CEnR research, resulting in delays or difficulties in receiving IRB approval in a timely manner. Some of the factors related to this challenge include the following: (1) Hesitancy reported by IRBs, when CEnR researchers include non-university affiliated clinics and staff as research partners; (2) Not having a standardized mechanism or process in place for non-affiliated community partners to serve as research partners within academic institutions; (3) Concerns related to the inability of the IRBs to ensure oversight of HSR protections for partnered community organizations who are interested in engaging in the process of research but are not affiliated with the academic IRB, which could lead to possible HSR violations.

Malone et al. [Reference Malone, Yerger, McGruder and Froelicher17] highlight an example of the IRB failing to the role of community partners as research partners. Researchers at the university hoped to use a CBPR approach where community partners would attempt to purchase single cigarettes to examine the impact of cigarette sales practices in an inner-city community in San Francisco, California. When researchers sought IRB approval, the IRB misunderstood the relationship between the community partners and the academic researchers and assumed researchers were using money to buy the help of community partners to commit the illegal act of buying single cigarettes. The IRB rejected this research proposal as they viewed it as a violation of HSR. This further hampered the research process as community partners felt betrayed by the IRB’s rejection, feeling as though the IRB chose to protect community predators (i.e. those selling cigarettes) over the health of the community itself [Reference Malone, Yerger, McGruder and Froelicher17]. This challenge highlights the need to not only clarify the roles, responsibilities, and relationships of research partners in the research process but also to include CBPR experts or ethicists in the IRB review of CBPR studies. Additionally, it showcases how IRBs are more inclined to protect institutional power at the expense of community partnership and collaboration [Reference Malone, Yerger, McGruder and Froelicher17,Reference Brown, Morello-Frosch and Brody23].

Recommendations and Lessons Learned

Some recommendations and lessons learned used by CEnR researchers to mitigate these challenges include allowing community partners to participate in certain aspects of the study if they completed additional training in CBPR and HSR from the institutions’ Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI), in addition to the basic HSR training required for all participants [Reference Chatterjee, Daftary, Gatison and Gillman14]. Dissemination of HSR training that is accessible to all community investigators prior to IRB engagement was also noted as an important way to satisfy IRB concerns around HSR [Reference Chatterjee, Daftary, Gatison and Gillman14,Reference Andrews, Cox and Newman22]. This demonstrates to the IRB that community partners are experienced in scientific and human subjects protection protocols [Reference Brown, Morello-Frosch and Brody23]. Additionally, explicitly clarifying the academic-community partner relationship in the IRB protocol further supports the partnered process. This includes specifying the duties and roles of the community partners as well as the methods of community engagement with community research partners. Doing so provides the IRB with transparency and more insight into the academic-community collaborative relationship, which can help improve the IRB approval process [Reference Malone, Yerger, McGruder and Froelicher17]. Finally, academic investigators conducting CEnR should ensure that all research projects are reviewed and approved by community representatives in addition to or as part of an IRB process. Andrews and colleagues described utilizing several of these strategies to address the challenges associated with including community members as coinvestigators on the IRB protocol [Reference Andrews, Cox and Newman22]. For example, the study sought to ensure an institutional faculty member with CBPR knowledge and experience served as part of the IRB. The program also provided training to IRB administrators, faculty, and community partners on the IRB process for CEnR. Additionally, the program implemented a process to allow community partners access to the electronic IRB application and acknowledgment as a coprincipal investigator, as well as instructional guidelines, templates, and algorithms to enhance the IRB navigation process [Reference Andrews, Cox and Newman22].

Challenge #2: Cultural competence, the language of consent forms, and literacy level of partners

The second major challenge in CEnR research includes obtaining alternative forms of consent outside traditional methods from immigrant and vulnerable populations. Studies have noted the difficulty in framing and accommodating certain cultural nuances unique to specific populations participating in the research process in IRB protocols and consent forms (i.e. cultural nuances that may fall outside the boundaries of western values inherent to the concept of informed consent) [Reference Johnson, Ali and Shipp16]. This also includes ensuring consent forms match literacy levels for community partners in addition to IRB protocol standards. Some of the factors related to these challenges include: (1) Difficulty in obtaining consent forms from immigrant populations (due to concerns about immigration violations) as well as vulnerable populations like sex workers or unhoused individuals who may be wary of documentation [Reference Johnson, Ali and Shipp16,Reference Pirie and Gute18,Reference Hyatt, Gute, Pirie, Page, Vasquez and Dalembert24]; (2) IRB-approved written consent form templates language that is too technical/complex to translate in a way that would properly capture and summarize the nature and content of the research study. These complexities can often prove difficult for non-English speaking communities with a strong oral language culture [Reference Pirie and Gute18]; (3) IRBs preference for written documentation of consent. In some communities (e.g. undocumented immigrants, etc.), community members may be averse to signing any form of documentation due to fears of repercussions, even though they are willing to participate in research.

For these reasons, in some cases, verbal consent might be the only way these groups will agree to participate in the study.

Recommendations and Lessons Learned

Some recommendations and lessons learned that researchers have used to mitigate these challenges include providing supervision for non-native-speaking study participants by engaging bilingual community leaders to help facilitate verbal consent and, in some cases, written consent. In addition, obtaining human studies-certified interpreters for non-native speakers would help in the consent process [Reference Pirie and Gute18]. Convening an IRB with members educated in cultural nuances of the study population can help necessitate flexibility in the research project [Reference Johnson, Ali and Shipp16]. This can be especially beneficial for CBPR projects, which often need to have sufficient leeway for the project to adapt and tailor materials as needed to fit the community [Reference Pirie and Gute18]. In addition, conducting studies involving refugee communities and other immigrant groups may necessitate educating IRBs on cultural nuances that may not conform to western values of individual autonomy, self-determination, and freedom inherent to the concept of informed consent. Finally, IRBs can provide a waiver of written/signed informed consent, wherein documentation of verbal consent obtained through an interpreter is sufficient for community members to participate in the research process [Reference Johnson, Ali and Shipp16]. One example of this is the Pirie et al study. The goal of the study was to assess and control occupational health risks among immigrants in Somerville, Massachusetts using bilingual teen educators to gather information on self-identified immigrant workers living or employed in the city. One of the major study challenges was that the existing IRB-approved written informed consent form was too technical/complex and written at too high of a literacy level for community members to understand and provide consent. The IRB approval process was further delayed because several corrections were required to improve the survey flow for participant comprehension. To address these challenges, the study included bilingual adult community leaders to facilitate participant verbal consent for immigrant community members who were non-native speakers. In addition, human studies-certified interpretation was also available for non-English speakers. One unexpected outcome from the delay in IRB approval was that it provided an opportunity for community members and research staff to deepen mutual relationships of trust, expand community capacity through education in human participants' protection, and support the Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI) certification of community partners. [Reference Pirie and Gute18]

Challenge #3: IRBs apply formulaic approaches to CEnR

IRBs often review studies using a biomedical and behavioral framework, which may be inappropriate to the methodology, objectives, and purpose of CEnR [Reference Brown, Morello-Frosch and Brody23]. CBPR, in particular, is characterized by community involvement as collaborators in the research process, reporting back results to study participants and a bidirectional relationship between the research team and community members. In some instances, these processes may be unfamiliar to IRB review boards. Some of the factors related to these challenges include: (1) The nature of the CBPR process often poses a challenge to the IRB’s determination of which party (i.e. research team versus community collaborators) is in control of the flow of data produced by the study (2) IRBs are concerned with how data should be shared with community participants (3) IRBs are concerned with the nature and length of the relationship with the community.

Recommendations and Lessons Learned

Some recommendations and lessons learned that researchers have used to mitigate this challenge include conducting training for IRB reviewers to help them understand the principles of CEnR. Training can streamline the approval process by reducing delays and increasing the flexibility of the academic IRB review process. This can be implemented by inviting IRB and HSR administrative staff to CEnR-focused workshops to improve their overall understanding of the principles of CEnR, which in turn can help establish regular communication between researchers and IRBs [Reference Chatterjee, Daftary, Gatison and Gillman14,Reference Brown, Morello-Frosch and Brody23]. In addition, including faculty members with CEnR knowledge and experience or CEnR experts/ethicists, in the IRB review of applicable CEnR studies, will help the review process, as they can serve to educate other IRB members on the CEnR principles and methodology during the research process [Reference Malone, Yerger, McGruder and Froelicher17]. These experts can also work with IRB offices to develop processes supportive of CEnR, and training tools for community investigators in order to remove any barriers in the IRB review process. Overall, increasing IRBs' understanding and knowledge of CEnR will lead to strengthening their community composition, including community-level ethical considerations for policies, processes, and application forms.

One example of this is the Chatterjee et al study, which was a pilot nutrition program launched by community partners and evaluated by investigators at Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute (HPHCI). The goal of the study was to evaluate the impact of a new school food program on the health of students. The study was designed as a community–academic partnership where school staff and academic health centers were involved as stakeholders in the research process. At the study’s outset, the IRB expressed concerns about several components of the CBPR study, including supervision for HSR protections at a remote site from the academic institution. Because of these rigid requirements with regard to HSR protocols, an imbalance of power was created by prioritizing the academic institution’s demands over the needs of the community organizations. To address these challenges, the study investigators utilized training materials developed by Harvard’s Clinical and Translational Science Center (CTSC) for community investigators in CBPR projects to train community members in the research process. The training covered important topics for all investigators to understand when conducting HSR and allowed community/student investigators to participate in certain aspects of the study if they completed training from the institution’s CTSC on HSR and CBPR [Reference Chatterjee, Daftary, Gatison and Gillman14]. Overall, working with IRB offices to develop processes supportive of CEnR and training tools for community investigators can remove many barriers and maintain long-term relationships in communities. Training IRBs to understand CEnR principles also streamlines, reduces delays, and increases the flexibility of the academic IRB review process [Reference Chatterjee, Daftary, Gatison and Gillman14].

Challenge #4: Extensive time duration for IRB preparation and approval has the potential to stifle the relationship with community partners

The final challenge highlighted from the scoping review includes extended durations for preparing and submitting CBPR/CEnR research, which prolongs the approval process. These extensive time periods for the IRB review can often stifle the research process and the relationship/partnership with community stakeholders as well as community research partners. This challenge is heightened for researchers working with multiple IRBs such as local, tribal, and national IRBs, in addition to academic IRBs. Some of the factors related to these challenges include (1) different types of IRBs often have varying interests and stakes in the research process; (2) IRBs can have different review requirements, and processes which can contribute to extended processing and approval time (e.g. local and tribal IRB policies) [Reference Holkup, Tripp-Reimer, Salois and Weinert15].

Recommendations and Lessons Learned

Some recommendations and lessons learned from CEnR literature that researchers have used to help ease or speed up the review and approval process include identifying key stakeholders with influence in the community who can provide support with community buy-in for the research study [Reference Holkup, Tripp-Reimer, Salois and Weinert15]. Involving community partners in the research process and with the IRB as early as possible will also help with the review process, by minimizing any last-minute surprises that require revision or change in a study design or protocol [Reference Hyatt, Gute, Pirie, Page, Vasquez and Dalembert24]. Finally, implementing a process to allow community partners access to the electronic IRB application and acknowledgment as a coprincipal investigator, as well as instructional guidelines, templates, and algorithms to enhance the IRB navigation process will expedite the process. By doing so, community partners have a better understanding of the review process, which reduces the discordance between academic researchers and community partners in terms of the CEnR project.

One example of identifying key stakeholders can be found in the Holkup et al study. The goal of the study was to use family conference models to resolve problems with American Indian families struggling to care for an elder or resolve problems with a mistreated elder within a family system. This model provides a way for families to resolve problems while maintaining self-determination. The study encountered challenges concerning IRB requirements for informed consent. The structure approved by the IRB for gaining informed consent for the study disrupted the natural flow of conversations and the group dynamics of the group interviews. This study utilized action research process, which is a characteristic of CBPR that uses a cyclical and iterative process of planning, reflecting, reporting, and re-planning [Reference Israel, Schulz, Parker and Becker26,Reference Kemmis, McTaggart, denzin and lincoln27]. As a result, there was some difficulty in gaining true informed consent because of the nature of action research, to allow the project to evolve as the research progresses. It was difficult to specify explicitly what involvement in the research will mean for the participants [Reference Holkup, Tripp-Reimer, Salois and Weinert15]. To address these challenges, the study team identified key stakeholders with influence in the community who could provide support and improve buy-in within the community and the tribal IRBs. This sped up the process by reducing the scrutiny of the tribal IRBs to commence the research study.

In another example conducted by Hyatt et al, the goal of the study was to determine if an educational and training intervention involving both community partners and IRB leadership could resolve gaps in CBPR knowledge and mistrust. The study gave community leaders, particularly leaders in partner organizations, additional experience and training in survey development, implementation, and analysis, with assistance provided by co-investigators at Tufts University. The major challenge in working with immigrant workers was that protecting human subjects was a critical issue in which many community partners were not knowledgeable about the need for such protections or the role of the IRBs. To address and ease the review process, the lead investigators communicated IRB issues as often and as clearly as possible with both community partners and their own IRB to minimize last-minute delays and surprises. These communications were followed up with a written memo to both community partners and the IRB.

Discussion

CEnR is characterized by direct community involvement/collaboration and equal partnership with community members in the research process [Reference Balls-Berry and Acosta-Perez4]. Specifically, this bidirectional relationship takes into consideration multiple types of stakeholders in the research process and ensures that interventions are well-tailored and culturally and linguistically appropriate for the communities in which it will be implemented. This is often recognized as a key process for possibly reducing health disparities that result from structural racism [Reference Han, Xu and Mendez28]. CEnR provides an alternative approach to research compared to traditional forms of biomedical research which often separates interventions from its community context [Reference Holkup, Tripp-Reimer, Salois and Weinert15].

Increasingly, funding organizations, researchers, and communities recognize CEnR approach as an important methodology for understanding and addressing critical health concerns within communities [29,Reference Shore, Wong, Seifer, Grignon and Gamble30]. This is because of the collaborative approach CEnR utilizes, which establishes community members as equal partners in the research process and recognizes the unique strengths each partner brings to the research [Reference Shore, Wong, Seifer, Grignon and Gamble30].

IRBs ensure that research studies comply with applicable ethical standards and policies that protect research participants in a study. Our goal for this review was to identify barriers and hurdles that CEnR researchers encounter in seeking IRB approval for CEnR research and recommendations/lessons learned that circumvent these obstacles to obtaining IRB approval. Fifteen articles were included in this review and four categories of challenges were identified with subsequent lessons learned: (1) community partners not being recognized as research partners; (2) cultural competence, the language of consent forms, and literacy level of partners; (3) IRBs apply formulaic approaches to CEnR; and (4) extensive time duration for IRB preparation and approval has the potential to stifle the relationship with community partners.

Situating the findings from our scoping review into broader conceptual frameworks on community engagement may provide a roadmap for understanding how institutional and structural practices in IRBs can be enhanced to foster community engagement in research. For example, the Assessing Community Engagement (ACE) Conceptual Model demonstrates the dynamic relationship required to achieve health equity and systems transformation for health through meaningful community engagement [Reference Aguilar-Gaxiola, Ahmed and Anise31]. Domains specific to ACE can serve as possible drivers of change to improve IRB practice of CEnR and promote health equity.

Table 4 below summarizes the challenges and strategies to mitigate these challenges and recommendations for improving the review process. We have also included domains from the ACE Model to articulate opportunities for improving IRB practice as it relates to CEnR.

Table 4. Summary of challenges and recommendations for CEnR researchers engaging with IRBs

ACE, assessing community engagement; CEnR, community-engaged research; CTSI, Clinical and Translational Science Institute; HSR, human subjects research; IRB, Institutional review board.

Overall, the challenges highlighted in this review demonstrate the gaps that exist in obtaining approval for CEnR research. The concern of IRBs failing to recognize community partners as equal partners in the research study stems from the inability of the IRB to have true oversight of community partners involved in research, especially when community partners are not affiliated with academic IRBs. While this might be a legitimate concern, the nature of CEnR requires community partner involvement in the research process as key contributing stakeholders. By allowing community partners to participate in the research process, it leverages the opportunity for academic researchers to have direct access to contextualized local data otherwise not captured by traditional forms of biomedical research.

Secondly, it enhances the interpretation of research findings through an understanding of the local context provided by community partner involvement and provides opportunities for building human capital and a community resource infrastructure that can directly affect changes in local policy through participating community partners [Reference O’Brien and Whitaker32]. As such, IRBs need to recognize that the involvement of the community and its members as research partners as opposed to research subjects, maximizes community benefits and minimizes harm, which can lead to improved public health [Reference Shore, Wong, Seifer, Grignon and Gamble30].

From our findings, to ease IRB concerns about potential human subject violations, training community partners or involving them in workshops that cover HSR training (e.g. CITI training) can ease IRB concerns and help them perceive community partners as trained stakeholders with a basic understanding of HSR.

IRB review processes are rooted in biomedical and behavioral research frameworks and often do not have the flexibility needed to review CEnR studies [Reference Cross, Pickering and Hickey9,Reference Brown, Morello-Frosch and Brody23]. Therefore, it is imperative for institutional IRBs to be trained in the principles of CEnR and CBPR methods. This can assist in reducing delays associated with the review process as IRB members will understand the intricacies associated with this type of research [Reference Chatterjee, Daftary, Gatison and Gillman14,Reference Brown, Morello-Frosch and Brody23]. Some ways to address this can include: (1) having IRB members participate in CBPR and CEnR workshops to gain a better understanding of the process; (2) creating a knowledge exchange program between community advisory boards and IRB members; and (3) including institutional faculty members with CBPR or CEnR experience as members of the IRB. All of these activities can provide IRBs with increased knowledge and exposure to CEnR; thus, removing barriers to the ethical review process and shortening the extensive time duration for IRB review and approval.

CEnR engages different community groups, which means that other IRBs like tribal or local IRBs may have to be involved in the ethics review process. Identifying key stakeholders with influence in the community to promote buy-in of the CEnR research project can help to speed up the research process. Through the influence of key stakeholders, community members are much less hesitant to participate and are more accepting and willing to engage in the research process. In addition, engaging and involving community partners early on in the research process can also help reduce time constraints that may arise during the review process [Reference Holkup, Tripp-Reimer, Salois and Weinert15,Reference Hyatt, Gute, Pirie, Page, Vasquez and Dalembert24].

More so, IRBs must understand that certain accommodations that are nontraditional to biomedical research may need to be included for CEnR or CBPR studies to account for language barriers and varying literary levels among community partners and allow for greater cultural competency. The inclusion of bilingual interpreters to provide verbal consent for partners, or allowing verbal consent without having partners sign a document will be key for involving some vulnerable groups like undocumented immigrants, etc. Summarily, IRBs need to be flexible in the research process, especially for studies involving vulnerable communities whose cultural context may differ from western norms and values [Reference Johnson, Ali and Shipp16,Reference Pirie and Gute18].

Our aggregated findings are consistent with individual reports from CEnR investigators. For example, an article on overcoming barriers to effective CBPR research in US medical schools reported institutional barriers to their CBPR associated with limited understanding of CBPR, the perception that CBPR lacks rigor, and concerns of objectification of the community in research [Reference Ahmed, Beck, Maurana and Newton33]. Another study reported results of a content analysis of 30 institutions and found that review boards often favored traditional biomedical research frameworks, which could unknowingly set this as the standard for all forms of research [Reference Flicker, Travers, Guta, McDonald and Meagher34]. Similar to our review other studies recommend that IRBs receive training in the principles of CBPR and IRBs should require CBPR investigators to document the process of key decision-making as regards the study design and community consultation related to the design [Reference Flicker, Travers, Guta, McDonald and Meagher34,Reference Plunk35].

There are several strengths to this study. First, CEnR researchers have encountered and discussed some barriers to IRB approval [Reference Fullerton, Anderson, Cowan, Malen and Brugge21,Reference Hyatt, Gute, Pirie, Page, Vasquez and Dalembert24,Reference Paskett, Reeves and McLaughlin36]. This is the first scoping review that documents the challenges that CBPR investigators have with obtaining ethical approval from IRBs. Our review generated a total of 15 articles published over the course of 12 years, increasing in frequency in the 2010s and spread across numerous journal types. The diversity in journal types and disciplines that have explored this topic as well as the increased frequency of publications on this topic over the last two decades points towards the growing relevance and prominence of CEnR across disciplines and highlights the role this scoping review can play in coalescing a knowledge base on IRB practice.

Additionally, this review reports on lessons learned from the field and recommendations that can assist CBPR investigators in obtaining approval from ethical review boards. The collated recommendations from this study provide a catalog of strategies that IRBs can adopt to understand CBPR methodologies and be inclusive of community partners in the research process, which enriches the research process and contributes to capacity building for community partners who may seek to conduct their own future research. This review is also timely as it complements the growing requests from funders (e.g. NIH) for more collaborative and community-engaged approaches to tackling health disparities, structural racism, racism in healthcare, community mistrust, and health inequities [Reference Minkler, Blackwell, Thompson and Tamir8,Reference Kwon, Tandon, Islam, Riley and Trinh-Shevrin37–Reference Collins, Adams and Aklin40].

There are several limitations to this study. This scoping review included a combination of research studies and expert opinions/reports. While these expert reports are important, they include second-hand accounts of the researchers’ experiences seeking ethical approval for CBPR and are not primary research, which might have provided stronger evidence for this topic. Another limitation of the review was that many studies included were not consistent in reporting demographic data of the community partners or target population, which made it difficult to examine and report on any relationship between the target population and some of the IRB approval outcomes of the study. Only a few studies reported on the process of gaining approval from the IRB, and only one study reported on the process of denial from the IRB. Most of the studies that we reviewed reported obtaining IRB approval, but had limited to no details on their experience in engaging the IRBs, nor did they include a related process paper on their engagement with the IRB. Regardless of approval/disapproval, more studies might consider documenting their process of engagement with IRBs both academically and within the community. In addition, many of the recommendations reported in the review are specific to the nature and context of the research topic and might not be generalizable to all forms of CEnR. Several studies reported on potential recommendations that might ease the process, however, Investigators had not tested or implemented these recommendations in their study settings; therefore, there was no evidence or outcomes on the success of these recommendations. It is also important to note that some of the challenges encountered in CEnR studies also exist in some traditional forms of biomedical research studies (e.g. the need for consent to be understandable and available in languages spoken by the community members). Future studies can implement these recommendations to document if and how they might work across different community study settings and with different community partners.

Our findings are important given the 2021 statement from the Association for the Accreditation of Human Research Protection Programs (AAHRPP) for the support of community engagement as a result of the pandemic [41]. The standard put forth by AAHRPP has always included a requirement to engage in community research, the urgency for this requirement was further highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic, the consequences of which disproportionately affected the most vulnerable communities in the USA.

The standards state that AAHRPP-accredited organizations remain committed to finding innovative, effective ways to engage and protect vulnerable communities. The standards include: (1) Following written policies and procedures that establish a safe, confidential, and reliable channel for current, prospective, or past research participants or their representatives that permits them to discuss problems, concerns, and questions; obtain information; or offer input with an informed individual who is unaffiliated with the specific research protocol; (2) Conducting activities designed to enhance the understanding of human research by participants, prospective participants, or their communities, when appropriate; (3) Promoting the involvement of community members, when appropriate, in the design and implementation of research and the dissemination of results [41].

This is an important statement from the AAHRPP, as it means there is less of a need to advocate for the inclusion of community engagement in the IRB process, and more need to help IRBs and researchers learn effective strategies for their settings and context.

In conclusion, findings from our study suggest that IRBs might benefit from more training in CEnR, its requirements, and its methodologies. Future studies should seek to engage, maintain regular communication with IRBs and educate IRBs on the CEnR research process, identify lessons learned to advance the field, and consider flexible and alternative processes for ethical review and approval of CEnR compared to traditional biomedical research studies, which view community members as research subjects instead of recognizing community members as research partners.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2023.516.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Arthur Ashe Institute for Urban Health, Family Health Centers at NYU Langone, India Home, Hamilton-Madison House, Korean Community Services of Metropolitan New York, Inc., Fifth Avenue Committee, National Asian Pacific Center on Aging, and AARP New York, who all serve on the NYU Langone CTSI Community Advisory Board (CAB). The CAB members were invaluable in the conception of this manuscript. Their incorporated feedback from CAB meetings and real-world experiences with IRBs shaped the conception of this manuscript.

We acknowledge the editorial assistance of NYU Langone’s Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI), which is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health, through Grant Award Number UL1TR001445.

Disclosures

The authors declare no competing interests.