Figure 1. Clarke’s Latin: Complete Course

Never has the phrase annus horribilis seemed more applicable than in this past dreadful year. Virgil's lacrimae rerum have, I imagine, been with us all throughout; though I doubt that it was ‘the tiers of things’ he had in mind.

Though very few silver linings have presented themselves beneath the black cloud of the coronapocalypse, I have endeavoured to use such extra time as it has afforded in the furtherance of my Clarke's Latin project. Happily I was at last able in November to publish all 11 volumes – five parts, their corresponding answer keys and a batch of practice papers in the new Common Entrance format. (Part V completes CE Level 3. Depending how long the current lockdown persists, I may well be some way towards finishing the final two parts – for Common Academic Scholarship and Eton scholarship/GCSE/AS – later in the year.)

I began work on the project in the summer of 2019. I had by then realised just how much practice a pupil needs before genuinely mastering any given area of the language. Too often, a class I believed to have fully grasped an element of grammar would, a few topics later, appear to have forgotten that element in its entirety. I wanted to create a series of books whose exercises were so numerous as to bring that mastery inevitably about, while rescuing teachers from the burden of writing endless materials themselves.

This I was able to do only with the assistance of modern technology. I developed a method of producing Latin words and simple phrases, as well as their English translations, through computer generation. The computer then arranges these in a random order, creating exercises which are not only copious but in fact contain every possible permutation of the available vocabulary and grammar.

Thus while my first Latin course, Variatio, provided 60 questions on the present tense of first conjugation verbs, Clarke's Latin gives 960. Over the remainder of Part I, there are 1000 questions on the nominative case of mensa, another 1000 on the accusative and more than 3000 on the remaining cases, prepositions, interrogatives and imperatives. Some are individual words and phrases for analysis and translation; others are grammatical, or etymological; others still, complete sentences from Latin to English and vice versa.

The entire course spans more than 2200 pages and a 250000 words, including 20000 questions and 30000 words of continuous Latin prose. As such, it is one of the most extensive sets of rudimentary Latin resources ever created.

I also wanted to approach the language in a way which compelled the student to be analytical, with a close eye for detail, from the very start. More than anything else, my guiding principle through the past ten years of teaching has been that I always want my pupils to understand why something means what it means, not merely to be able to hazard a translation.

To this end, I altered somewhat the order in which I introduced the very basics. Every traditional course I have encountered has always followed the same pattern: amo; negatives and conjunctions; the nominative case of mensa and finally the accusative case. After these introductory exercises comes the first unseen which, not unreasonably, contains adverbs and subordinate clauses in order to make the passage flow and function as a story.

Unfortunately, it has been my experience that expecting pupils to handle these further complexities intuitively has often met with significant confusion. Clarke's Latin, therefore, teaches adverbs and then subordination as discrete topics after the nominative. At this stage, a system of analysis is put into place. The subject is underlined; verbs put in a box. Adverbs are bracketed, while sub-clauses are split off with slashes.

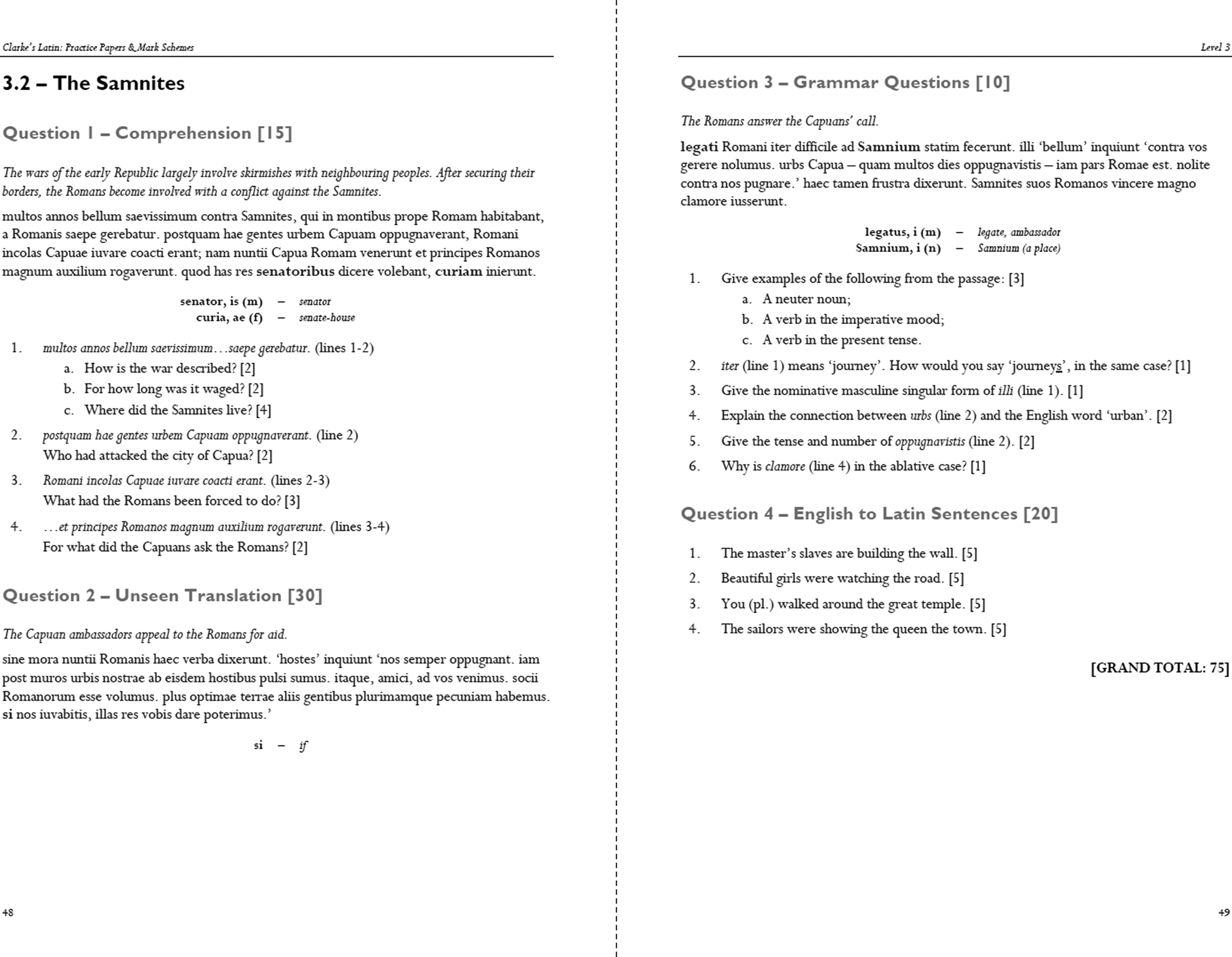

Figure 2. Sample Comprehension, Translation and Grammar Questions

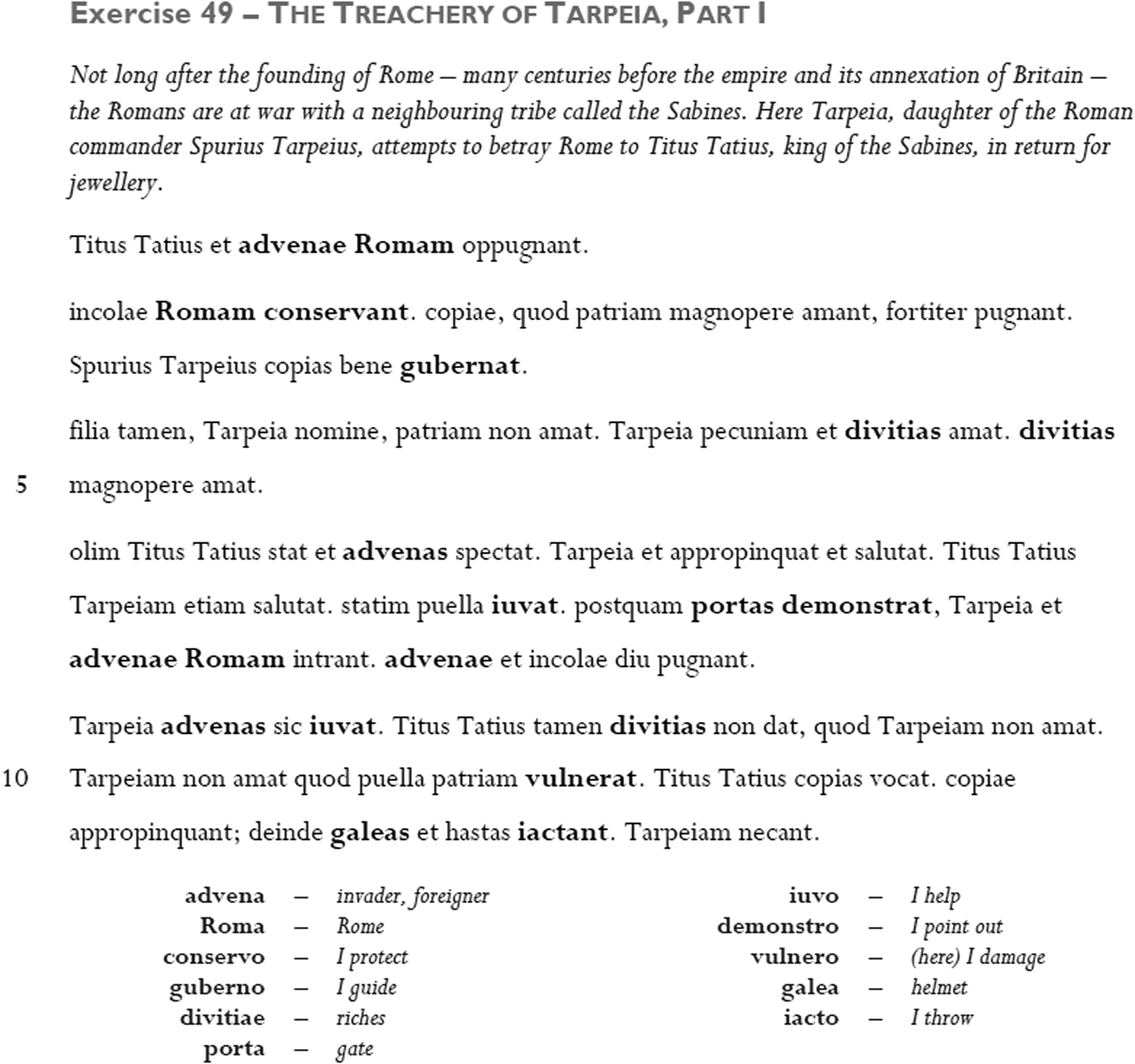

Figure 3. Sample Translation

Figure 4. Sample Grammar Explanation

The first unseen translation follows, without the added complication of the accusative case. Admittedly, producing Latin prose with only nominatives is a little excruciating, but the benefits to the students’ understanding as a result of this simple practice have been immense.

Here is the opening paragraph of that first unseen (entitled ‘A Winged Intruder’), along with its analysis. (Words in bold are glossed.)

(olim) schola laborat. grammatista imperat. iuvat [et] nuntiat, / [dum] puellae laborant/. puellae (bene) laborant, / [quod] grammatista spectat/. / [si] puellae (diu) laborant/, grammatista laudat. (subito) intrat vespa. vespa (celeriter) volat et (magnopere) bombitat. (mox) puellae turbant. / [ubi] vespa appropinquat/, puellae [et] clamant [et] reformidant.

Figure 5. Sample Translation

Once pupils have the hang of subordination and can cope with continuous prose – and, indeed, their first Latin composition, which follows the exercise above – they move on to the accusative case. The system of analysis grows with each chapter to encompass other cases and parts of speech.

The passages themselves are, I hope, entertaining and of historical interest. Some, particularly at the outset, are confected creations of my own; others I adapted from Livy, Tacitus, Pliny and a variety of other authors. Greek mythology features heavily, as well as Roman history. A few anachronisms pop up from time to time – Hercule Poirot, ’Allo ’Allo! and Nigel Farage, among others.

Conscious of teachers’ ever-increasing workload, I have endeavoured to make the books as useful as possible. As well as the quantity of resources, they are in workbook format, eliminating the need for files or exercise books. The answer keys allow pupils to mark the majority of their own work, while teachers need only see to significant exercises such as unseens, comprehensions and grammatical questions based on passages. Differentiation too is built into the course, with simple materials which are appropriate for the weakest as well as tough English to Latin sentences and prose composition for the most able.

It has been a colossal undertaking to produce but I am delighted to have emerged the other end with a set of resources which, so far, have done a great deal for my own pupils. I very much hope that Clarke's Latin will continue to gain traction in the coming years and provide similar assistance to colleagues elsewhere.

Figure 6. Sample Grammar Explanation