Introduction

The class for this study is a Key Stage 5 class of 10 pupils in state education. The class is mixed-gender and mixed-ability, and pupils have varying backgrounds with respect to Classical study, ranging from no prior experience to study at Key Stage 3 and Key Stage 4. Two of the pupils in the class have played Assassin's Creed: Odyssey before it was used as part of the lesson sequence. Three of the pupils are high attainment, and one has diagnosed Special Educational Needs. There are ongoing issues with truancy for four of the pupils, and a motivation gap with online attendance for an additional three, making it difficult to observe any patterns in their performance. As a result, the work and progress of the three pupils with sufficient attendance in the sequence will be used in discussing the sequence. Pupils were given pseudonyms to ensure anonymity and the only activities conducted were those which would usually take place as part of my standard teaching practice.

The lessons in the sequence were four 55-minute lessons covering the study of Olympia as part of the sanctuaries chapter of the A Level Greek Religion module, with the first two of these taking place under remote-learning conditions. During these lessons, pupils had variable accessibility to appropriate technology, with some pupils joining the lessons on their mobile phones. As a result, this may have impacted how pupils engaged with these lessons due to potential time-lags and hardware issues. Moreover, due to time-constraints of the research, these were the first lessons I taught this class, which may have affected engagement with activities, particularly in the lessons which took place online.

Literature review

Before discussing how to apply video games effectively in a classroom setting, learning outcomes should be considered. As discussed by Connolly et al. (Reference Connolly, Boyle, MacArthur, Hainey and Boyle2012) and Bass (Reference Bass2020), there are a range of potential learning outcomes from video games, including but not limited to motor skills, knowledge acquisition, and social skills. Mitchell and Savill-Smith (Reference Mitchell and Savill-Smith2004, 58) suggest that they also encourage creativity and visualisation, vital skills for encouraging pupils to evaluate the ancient world as part of an A Level. Since this study is centred on exploring effective use of video games for teaching Key Stage 5 Classical Civilisation, and hence prescribed exam content, the aims of this lesson sequence should be centred around knowledge acquisition, as well as development of evaluative skills which are key to being able to answer extended essay questions at A Level. Other learning outcomes such as developing engagement and interest in the ancient world and understanding of Classical Reception are also important long-term goals; however, these will not be assessed directly as part of the sequence due to time constraints.

Ritterfeld et al. (Reference Ritterfeld, Shen, Wang, Nocera and Wong2009) suggest that the learning process is boosted through interactivity within games, whereby pupils are learning through behavioural responses and experiencing real time feedback from the game. This seems to draw on the idea of ‘situated learning’ as discussed by Lave and Wenger (Reference Lave and Wenger1991) who suggest that during the learning process, action is most significant. For example, pupils, rather than just watching a game, must interact with prompts in it to become active and engaged in the learning process. Interactivity is also a vital part of effective Assessment for Learning (AfL). Harrison and Correia report that ‘frequent and interactive assessments of students’ understanding’ enables teachers to understand individual student needs more accurately and adjust teaching (Reference Harrison, Correia, Maguire, Gibbons, Glackin, Pepper and Skilling2018, 195). As such, by effectively embedding game interactivity, I should be able to gain a better understanding of pupils’ learning and have a better insight into shortfalls to plan strategies moving forward.

A slightly different approach to interactivity and learning in games has been discussed by Nicholls (Reference Nicholls, Natoli and Hunt2019) in his innovative work on using models to teach ancient Rome. Nicholls discusses encouraging pupils to create their own 3D images of sites they are studying and suggests that in doing so pupils are ‘hypothesising and arguing’ based on archaeological and textual evidence (Nicholls, Reference Nicholls, Natoli and Hunt2019, 135). Hypothesising and arguing are high level Bloom's taxonomy skills (Gershon, Reference Gershon2013, 39). Hence encouraging pupils to undertake these via game play, with or without scaffolding, allows me to assess pupils’ understanding at a more complex level than recall activities would, and therefore allows for assessment of skills which are more representative of those required for exams. Nicholls's study nevertheless comes from exploring such tools in university courses, an environment in which it is easier for an individual teacher to tailor requirements for a course, and hence easier for the teacher to find lesson time to teach and use modelling software. For example, Nicholls himself mentions that he developed a 3rd year course based on modelling to replace what would otherwise be an essay assignment (Nicholls, Reference Nicholls2016, 28); this would be difficult to achieve in a school environment. Furthermore, while pupils in a university may have access to a computer to be able to participate in such a study, not all pupils in secondary schools have access to appropriate technology, particularly during COVID homeworking, to be able to engage in such a process. Such limitations have been identified before, for example by Baek (Reference Baek2008) who suggests that ‘there are six challenges which educators who wish to implement video games into their teaching face, namely: the inflexibility of the curriculum, the negative effects of gaming, students’ lack of readiness, lack of supporting materials, fixed class schedules, and limited budgets (Baek, Reference Baek2008, 665). As such, my lesson planning needs to consider the need to adapt the game and its use to the curriculum and school structure, while including hypothesising in an alternative format.

To identify effective application of the game in a classroom setting, the study conducted by Karsenti and Parent (Reference Karsenti and Parent2020) was consequently particularly useful in my planning. While this study took place in Canada, where the education system may be less nationally prescriptive than in England and Wales, the use of the game in a school environment has proved to be a valuable model for developing my own teaching practice using Assassin's Creed as a tool. In the study, teachers used games to enrich lessons, but pupils were not able to play, which is comparable to my own teaching environment. From the study, pupils found that the experience of using the game was more valuable when the teacher directed the use of the game, explaining expectations of what they should be doing with the material, and used this as a springboard to ‘historical thinking’ (Karsenti and Parent, Reference Karsenti and Parent2020, 36). The role of the teacher is particularly important as Robison (Reference Robison2013, 578) highlights: ‘if a battle proceeds differently in a role-playing situation than it did in actuality – which is almost inevitable – students are not learning history.’ Nevertheless, McCall (Reference McCall2016) as well as Metzger (Reference Metzger2010) highlight the potential use of counterfactual examples as educational tools by providing pupils with secondary literature and other depictions of the event or place being portrayed in the game to help pupils evaluate and analyse the game. As a result, ‘the students have the ability both to learn from the experience of the game in a counterfactual manner, as well as learning from the historical sources which can inform their understanding of the event in which they just participated or presided over’ (McCall, Reference McCall2016, 527). Counterfactual discussions could therefore be successfully generated from a video game, where pupils may be asked to evaluate the effect of artistic changes on how certain things are presented, and potential reasons for the changes. Furthermore, such a discussion provides opportunity for genuine moments of dialogic talk, as proposed by Alexander (Reference Alexander2004), with a broad range of genuinely open questions which pupils can choose to reflect on and discuss, incorporating also the quality, student-centred interaction which Black and Wiliam (Reference Black and Wiliam1998) describe as being a central part of effective AfL. As such, counterfactual discussions draw on effective AfL practices by being valuable springboards for effective classroom talk and should be included in my lesson planning.

Also useful for developing my ideas on using Assassin's Creed: Odyssey in lessons was Hinde (Reference Hinde2019) on creative approaches to using the game in classrooms. The blog suggests that ‘the game can be streamed into documentary-style videos on relevant topics’. Indeed, this is particularly easy to transfer to a classroom, and can be done in an age-appropriate way, with Ubisoft releasing educational versions of the game, without the combative aspects of gameplay, where the player can take a tour of ancient sites of historical and cultural interest (Porter, Reference Porter2018). Furthermore, this teacher-guided approach may reduce the potential effects of insufficient game proficiency hindering pupil learning, discussed by Mitchell and Savill-Smith (Reference Mitchell and Savill-Smith2004, 59). Nevertheless, Hinde's approach of breaking up a lesson with a ‘2-minute walk-around [the Acropolis] to deliver all the key facts and figures’ (Hinde, Reference Hinde2019) removes some of the key benefits of video games which have already been discussed in the review, particularly the interactivity discussed by Ritterfeld et al. (Reference Ritterfeld, Shen, Wang, Nocera and Wong2009). As such, while Hinde's blog is an excellent springboard for further ideas, these need to be developed further with an eye to other scholarship.

With this in mind, an approach to utilising the game needs to be found which preserves the benefits of the format to the greatest possible degree, while combining this with the classroom appropriate ‘documentary-style videos’ suggested by Hinde (Reference Hinde2019). As such, some of the research on using documentaries in education may be helpful for considering best practice in using the game's Discovery Tour. It should be noted that, unlike in a documentary, in a game the teacher can have full control over the commentary being provided with the footage and over the angles of perception and buildings explored. As such, games and documentaries are not entirely similar, and research may not be precisely transferable. Marcus and Stoddard (Reference Marcus and Stoddard2009) discuss the importance of scaffolding pupils’ viewing of documentaries, for example by ensuring pupils can use data collected from the documentary to give them an entry point into a discussion. This is done when ‘students can fill in a table or graphic organiser that asks them to chart their affective reactions…and what questions have been raised’ (Marcus and Stoddard, Reference Marcus and Stoddard2009, 283). While researching effective uses of documentaries, it is interesting to note that research on how to use these appropriately has been sparse. For example, in searching through the archives of the Journal of Classics Teaching, four articles contained references to using documentaries within the Classics classroom; however, only one mentioned any methodology to approaching the use of documentaries. Day (Reference Day2019, 10) says ‘regular pausing for discussion and breaking the viewing of the hour-long documentary up over three lessons were important. However, it was also important to me that this was not their only source of information about the revolt' (although it is not clear how this conclusion was reached).

A similar tool to documentaries is the YouTube video. Like games, these videos have a high entertainment value and are easily accessible by pupils from home, so research in this space is also helpful for understanding effective use of games in the classroom. Fleck et al. (Reference Fleck, Beckman, Sterns and Hussey2014, 34) suggest that to successfully integrate a YouTube video in a classroom it is necessary to be ‘explicit in its intended use’ and where something is used usually for entertainment purposes, as a video game is, it is particularly important to explain its use in the classroom. The study found that YouTube videos were helpful when pupils were encouraged to answer questions on a topic prior to and after viewing the video, including small group and large group discussion. This aligns with the research conducted by Lindstrom (Reference Lindstrom1994), although in a business education environment, that students perform better on recalling materials when they not only see them, but also hear about them while simultaneously performing some action in response to the materials being presented. This also fits with the earlier mentioned ideas of situated learning, where actions are important during a learning process and the study of Dempsey (Reference Dempsey1996) which found that students became frustrated with a game if they were not given a goal towards which they needed to work. Providing pupils with an opportunity to reflect on the purposes of an activity is also integral to effective AfL. Both Richards (Reference Richards2015) and DeLuca et al. (Reference DeLuca, Chapman-Chin, LaPointe-McEwan and Klinger2018) conclude that learning is more effective when pupils are aware of what they are learning to be able to reflect on the learning gap and begin to consider how learning strategies can be used to help them close the gap. Furthermore, it is vital to provide a context for pupils to be able to reflect on both their learning and any feedback they receive to be able to connect it to expected learning (Hattie and Timperley, Reference Hattie and Timperley2007, 82). As such, it will be important to give pupils an opportunity to reflect on why they are using the game, explicit instruction on how they can use it to bridge learning gaps, while also highlighting potential limitations.

From this review, the research which will be particularly relevant to my own lesson sequence will be that conducted by Karsenti and Parent (Reference Karsenti and Parent2020), Hinde (Reference Hinde2019), and Marcus and Stoddard (Reference Marcus and Stoddard2009). From these, it is important that my use of video games always includes critical evaluation and engagement by both teacher and pupils, as well as space for pupils to engage in live response to the game stimulus. Ritterfeld et al. (Reference Ritterfeld, Shen, Wang, Nocera and Wong2009) research on game interactivity is also crucial as it highlights the importance for me to maintain the benefit of video games by ensuring that interactivity is re-introduced after the adaptation of the game for a classroom environment. Moreover, McCall's (Reference McCall2016) research highlights the potential to use the game's sometimes counterfactual depictions in developing evaluative skills through dialogue. Students’ progress will be measured through qualitative analysis of my own observations, of informal quizzes done at the end of lessons 1 and 4, as well as of a summative progress test which pupils complete a week after the last session of the sequence, marked by myself and reviewed by the usual class teacher. Evaluation is to be completed qualitatively since a focus of my lesson sequence is on the learning experience resulting from applying teaching strategies and qualitative evaluation is an effective means for understanding ‘how people see things’ (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Bogdan and DeVault2016, 18).

Lesson sequence

Lesson 1: Planning

Activities in the first lesson were designed for pupils to gain familiarity with the layout of Olympia and the temple of Zeus. Pupils went on a virtual tour of the sanctuary of Olympia using pre-recorded game footage, which I used to illustrate key features and spaces. A benefit to this approach was being able to use in-game features to focus on specific buildings so pupils could see exactly what I was describing and experience the spatial relationships between them (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Game footage showing spatial relationships between temples from different angles.

Source: Ubisoft.

This was done in response to Hinde's (Reference Hinde2019) idea of pre-recorded teacher walkthroughs to highlight learning points and to mitigate the problem of technological aptitude raised by Mitchell and Savill-Smith (Reference Mitchell and Savill-Smith2004, 59). Pupils were encouraged to evaluate their learning by using the like function in teams to vote for which building they did not see on the tour. The like function allowed all pupils to participate in formative assessment in a quick and low-stakes way, reintroducing interactivity into the process. Following this, pupils were presented with various depictions of the temple of Zeus and its artworks as well as a walkthrough around the Assassin's Creed model. Pupils were encouraged to verbally evaluate the relative merits and drawbacks of the different depictions, building on Karsenti and Parent's (Reference Karsenti and Parent2020) discussion of critical engagement with games, as well as including an element of interactivity as suggested by Ritterfeld et al. (Reference Ritterfeld, Shen, Wang, Nocera and Wong2009) through discussion in response to visual cues. Pupils were also encouraged to evaluate whether they found game models helpful and concerns they had with using these, allowing for critical interpretation of the game as well as reflection through evaluation and dialogic talk. As a plenary, pupils were given a short formative quiz on their learning to identify gaps in evaluation of sources and factual recall. Pupil learning was evaluated through qualitative evaluation of verbal responses to in-class questioning, as well as their responses to the end of lesson quiz.

Evaluation

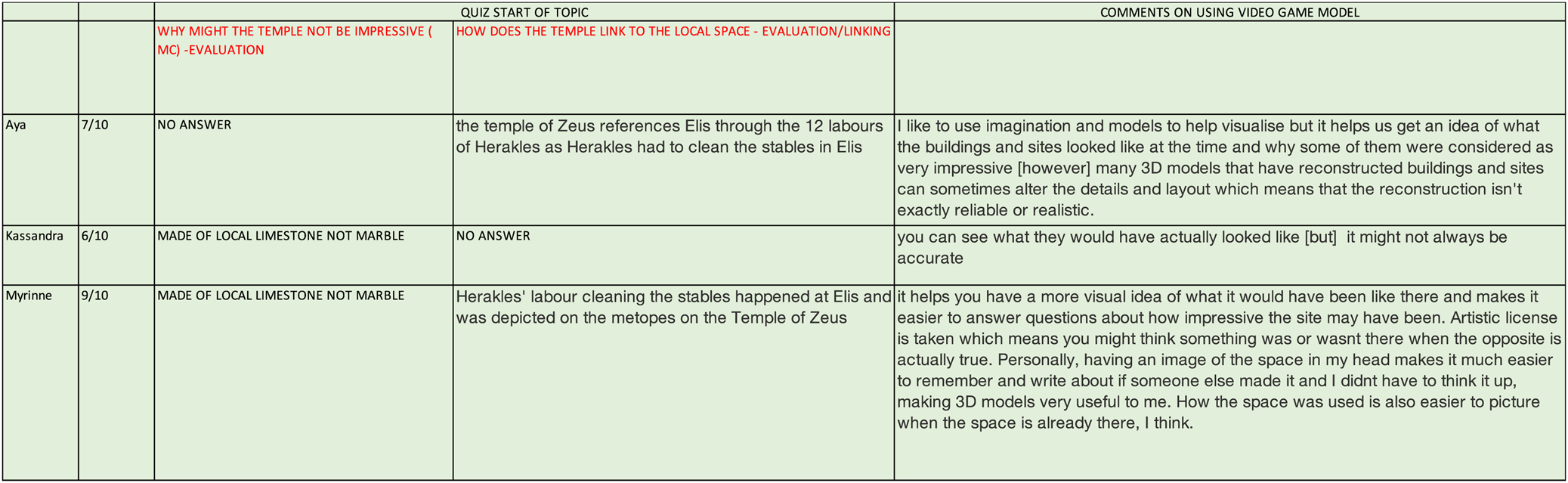

After the in-game flyover of the site, pupils all identified the building which did not exist in Olympia, suggesting that the visual depiction of the space combined with teacher narration may have been helpful in encouraging pupils to reflect on the space and its features. It is however unclear to what extent all pupils reflected on their learning from the game since as soon as stronger pupils started to vote, weaker pupils seemed to gain the confidence to answer, and therefore might have simply been copying the answers given by their peers. When evaluating merits and drawbacks of the different models, Aya suggested that she found the game helpful as it ‘helps us get an idea of what the buildings and sites looked like’ and ‘why some of them were considered impressive’, sentiments which were echoed by Kassandra. This suggests that the model helped pupils to visualise and evaluate the site in terms of its physical impact. Myrinne echoed her peers’ suggestions and also commented that ‘having an image of the space in my head makes it much easier to remember and write about if someone else made it and I didn't have to think it up’. This suggests that games may potentially simplify visualisation for some pupils and could be helpful for reducing cognitive overload associated with having to imagine and analyse simultaneously. Pupils were, however, also somewhat sceptical of the game, citing accuracy concerns and the potential that game developers took artistic licence, suggesting a critical engagement with the game as a source of information and evaluation and hypothesising about its content, thus application of higher-level Bloom's taxonomy skills. In their quiz, pupils were able to successfully show recall of specific features when they were given in multiple-choice format. Nevertheless, some struggled when they were asked to evaluate information, for example explaining how the temple of Zeus links to local myths, and also struggled to distinguish similar artworks (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Summary document of plenary quiz and comments on using the game from lesson 1.

This is understandable, since the metopes and the pediments are one of the least accurate parts of the Assassin's Creed: Odyssey model. It seems therefore that while counterfactuals may be helpful, it is important to devote sufficient time into also looking at the space from a solely factual perspective.

Lesson 2: Planning

The lesson aims were to build an understanding of the key features of the Altis, with a focus on pupils being able to discuss the appearance and significance of the chryselephantine statue of Zeus at Olympia and the Ash Altar. Pupils virtually visited the statue via the game and were encouraged to think about its visual impact, as well as any problems with the depiction as an interpretation, via verbal questioning. While ‘visiting’, I gave some contextual information on the statue. Pupils were encouraged to feedback about the ‘visiting experience’ and answer questions to think about how it was made and its impact, the answers to which I analysed to evaluate pupil learning. This activity built upon the idea of ‘situated learning’ (Lave and Wenger, Reference Lave and Wenger1991) since pupils were encouraged not just to watch and listen but to reflect and answer questions simultaneously. Moreover, pupils were made aware of the questions they were meant to be thinking about before their ‘visit’, drawing on the idea of Fleck et al. (Reference Fleck, Beckman, Sterns and Hussey2014) and Dempsey (Reference Dempsey1996) that to use games effectively pupils need to know what the intended goal of the activity is, as well as effective AfL practices as described by Richards (Reference Richards2015) and DeLuca et al. (Reference DeLuca, Chapman-Chin, LaPointe-McEwan and Klinger2018). After reading and predicting what the Ash Altar would look like from Pausanias’ description, pupils were asked to compare their interpretations with those of the game and offer comments on similarities and differences to how they imagined it, again using the game to build higher-level skills of prediction and evaluation. This allowed pupils to engage in critical evaluation of the game's depiction by first using a source to predict the space as suggested by Nicholls (Reference Nicholls2016), and then to evaluate the Assassin's Creed: Odyssey depiction as a counterfactual, as suggested by McCall (Reference McCall2016) and Metzger (Reference Metzger2010).

Evaluation

The counterfactual activities prompted some productive discussion by three of the pupils in the class concerning how the Ash Altar was presented. For example, Myrinne mentioned that the size and composition were not depicted truthfully in comparison to her predictions based on Pausanias. In her analysis, she referred to specific details mentioned in sources, namely the altar being 22 feet tall according to Pausanias, displaying effective use evidence to support her critique of the game. As Myrinne is a high-attaining pupil, it is not clear whether this response was prompted by the activity or by a thorough grounding in using evidence to support her points, although her response may show that the activity was well-tailored in encouraging pupils to support their arguments with evidence. The same three pupils also engaged with discussion of the chryselephantine statue, evaluating how it might have been ‘intimidating’ to approach due to its scale and life-like appearance while also criticising its depiction in the game. For example, Myrinne suggested that the gold might have been distributed differently in real life to show reverence to the god, rather than using the gold on the throne, which she felt showed less devotion. This suggests a high level of evaluative interaction, by comparing the statue against predictions based on prior knowledge of its purpose. Moreover, pupils were engaging with the process of the tour as an ‘experience’ by explaining how, as a visitor, they were made to feel by the spaces. Although some pupils were able to engage with the activities, it was difficult to evaluate whole-class learning. While Myrinne and two others participated in discussion, neither Aya nor Kassandra contributed to the class discussion, and only answered interpretive questions when they were multiple-choice answers and they could vote for them (although this may be due to poor internet connectivity and hence difficulty in engaging with discussion). The non-participation in an online lesson is also evidenced by the fact that only five pupils accessed the whiteboard.fi document to annotate a map, and only two pupils, one of whom (Myrinne) was in the study group, added anything to the document in response to the activity. From discussion with the usual class teacher, participation in online lessons is a common issue. In future, it would be helpful to do this lesson in person and provide sentence starters and further question prompts to help scaffold the process of evaluation and comparison in the tasks.

Lesson 3: Planning

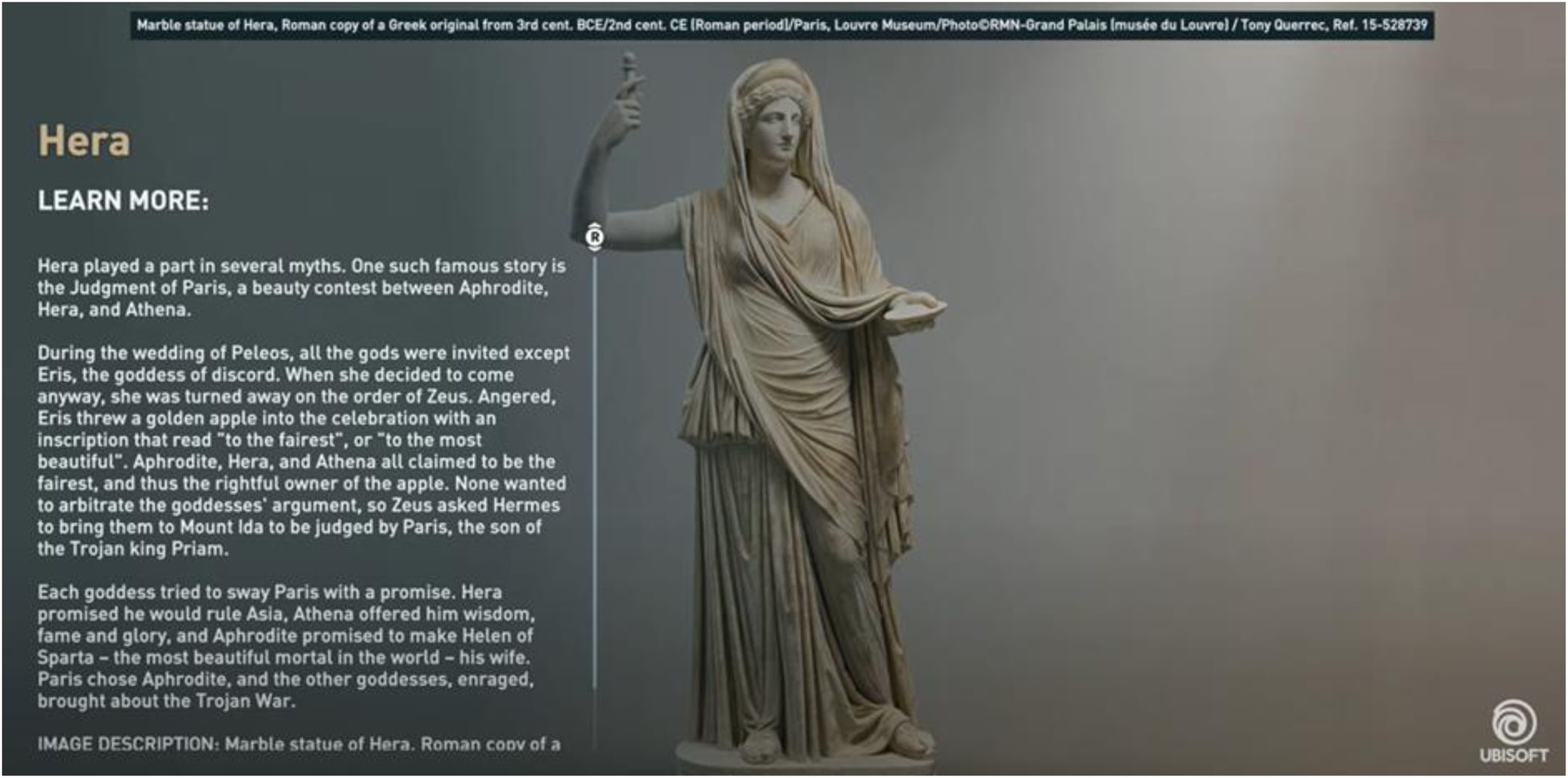

The aims of this lesson were for pupils to think about Olympia as the site of the Olympic Games. As part of this, pupils were given a worksheet with questions to answer while going on a pre-recorded in-game tour of Olympia. During the tour, the player goes to specific points in Olympia where a narrator discusses features of Olympia and the Olympic Games with dramatic footage to reinforce what is being said as well as inserts of useful sources (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Discovery tour game insert with additional information.

Source: Ubisoft.

The pre-written questions served multiple purposes; they included recall, comparison, and evaluation foci, thereby stretching pupils to develop not only factual recall but evaluative skills for their essay questions. By setting out the questions and pre-reading them with pupils, the game was given a purpose and made explicitly educational as suggested by Dempsey (Reference Dempsey1996) and Fleck et al. (Reference Fleck, Beckman, Sterns and Hussey2014). It also gave context to pupils’ learning (Hattie & Timperley, Reference Hattie and Timperley2007) and allowed pupils to reflect on expected learning and any learning gaps. Where relevant, I also made sure to verbally highlight any differences between the game and other depictions of the same source, thereby highlighting a space for counterfactual discussions as suggested by McCall (Reference McCall2016) and Metzger (Reference Metzger2010). By reintroducing a level of interactivity with the game through a series of questions to be answered at specific points in the game, I drew on ideas of ‘situated learning’ by encouraging pupils to respond immediately to game prompts. Pupil learning was evaluated through dialogic talk and directed questioning in response to activities.

Evaluation

Using questions to scaffold the tour elicited responses from all pupils in the class when they were questioned. As such, using the structure of the questions, as well as pausing the tour to discuss questions and answers, seemed to give pupils the support and confidence to respond or ask thoughtful questions. From observation, pupils showed critical engagement by asking follow-up questions about archaeological methods and ethical archaeology which resulted in the game model, suggesting that the game is a useful prompt to generate dialogic talk. These questions were prompted by my highlighting the presence of the hippodrome on the tour, and its comparative absence on other maps, or pointing out an empty space in the game where the Echo Stoa would eventually be built, showing the importance of teacher intervention in game models to guide how pupils interact with the information presented. Nevertheless, it was evident that further scaffolding was needed for some pupils. For example, Aya showed a certain hesitancy to put pen to paper when making notes under questions during the tour and showed preference for dictation of the ‘correct’ answer from myself and other pupils, rather than using the game tour and interpreting the information to answer. Another pupil had a similar response, trying to copy down what was said word for word, rather than paraphrasing. This could either show lack of comprehension of what the game had displayed, or alternatively a lack of confidence. As all pupils were able to answer questions verbally and ask relevant and insightful follow-up questions, it seems that pupils were able to complete the tasks, and hence met learning outcomes from the game, but were not confident in the process of writing an answer. In future, it may be helpful to model potential answers or provide some multiple-choice options, rather than expecting pupils to be able to condense information into their own written words.

Lesson 4: Planning

The lesson objective for this lesson was to finish learning about the events of the Olympics and compare the in-game presentation to other sources. Pupils continued with the Discovery Tour and filled gaps in their answer sheets in response to places and items found on the tour. Pupils then supplemented their learning by looking at sources, embedded in the PowerPoint, to reinforce places and objects seen on the tour. For example, pupils looked at the Echo Stoa in other sources and reflected on how it was used in the Games by recalling information from the tour, as well as predicting how it changed the nature of the Olympic Stadion and the religiosity of the Games using scaffolding questions provided verbally. In this way, the lesson drew more explicitly on the higher-level Bloom's taxonomy skills of evaluation, as well as the use of counterfactuals to get pupils to consider the space from a different perspective. At the end of the lesson, pupils were given an informal plenary quiz to check learning progress. Following the lesson, pupils were given a termly Progress Test, which is used to give their predicted grades. Pupils were set a 10-mark exam-style question on Olympia as part of this test to evaluate their whole topic learning, their ability to recall information learned in the sequence, and to observe any progress in using sources to support evaluation. The answers were reviewed to give a numerical mark for school data collection, as well as to qualitatively evaluate how pupils’ answers reflected their understanding of the material and ability to draw links between spaces and objects.

Evaluation

In the plenary quiz, all pupils provided a valid response to a question concerning sources which suggest that Zeus was central to the games. For example, Aya suggested that ‘if you were caught cheating, you would be beaten with a stick by the judge and you would be fined and told to put up a Zane with an inscription of what you did and your name’. Similarly, Kassandra suggested that ‘oaths to Zeus’ showed that Zeus was included in the proceedings of the Olympics. This aspect of the games was covered thoroughly, first during the tour, in which there was a re-enactment of a cheater being punished, then as a discussion of the tour questions, and as summary questions following the tour. In contrast to this, pupils perfomed poorly on question five. Kassandra was unable to recall either what the statue of Zeus was or how it was impressive, Aya could recall what it was but not how it was impressive, and only Myrinne was able to say that Pheidias ‘created the statue of Zeus [which was] very large and made of ivory and gold, expensive, imported’ [sic]. This difference could be a result of a motivation gap since Myrinne was the only pupil who had fully participated with the learning activities in lesson two on the Statue of Zeus and could answer questions on it a week later. Pupils’ progress tests showed significant improvements in both knowledge of Olympia and ability to use this knowledge to come to conclusions about the site of Olympia, with all pupils in the study scoring full marks in this question. Pupils were able to not only recall information but interpret it to discuss whether the ‘Olympic Games were merely a sporting event’. For example, Kassandra suggested that ‘the dedication of the games to Zeus is an example of religion playing an important factor in the Olympics’, saying that ‘each contestant and each judge had to swear an oath to Zeus to not cheat or judge unfairly’, further linking this to her knowledge of Zanes. Her ability to come up with these sources and link them to the question through evaluation shows a marked improvement from lesson one, when she struggled to evaluate how artwork could have local links even when this had been explicitly discussed. Aya also showed improvement in her answers, although her points were at times less sophisticated than Kassandra's. For example, Aya suggested that ‘the participants were told to swear an oath to Zeus that…you had been in training for a certain period of time’, which she interpreted as suggesting that ‘Zeus in particular, was important to the Olympic games’. Myrinne likewise showed good recall and evaluation, referring to the oaths to Zeus, direction of the Stadion, and Zanes to conclude that these showed the Olympics were ‘very religious and sacred to Zeus’. Reference to personal experiences of Olympia, for example using the pronoun ‘you’ in saying that ‘you wouldn't cheat’ and talking about running direction and its effect on religious experience, may suggest that pupils had picked up an experiential understanding of the site, rather than fragmented knowledge of individual sources distinct from any human experience, suggesting that the video game had been effective in encouraging pupils to visualise themselves in the place. Nevertheless, pupils were able to select sources they wished to use for the question, so it is difficult to evaluate how effectively pupils had applied this experiential learning to all necessary sources in the course. This consideration is particularly relevant, since the pupils had talked about the Zanes and Zeus at the Olympics thoroughly in lessons and were therefore making a point they were confident was relevant, rather than coming up with original evaluation.

Conclusion

Results of discussion, quizzes, and the progress test showed that Assassin's Creed: Odyssey could be a useful tool in teaching about Greek religion. It was particularly effective when used in a live-classroom environment, allowing pupils to have dialogic conversations about its strengths and limitations as a source, and when used as a springboard for counterfactual discussions. This was reflected by the fact that pupils were more confident recalling and evaluating materials covered in person rather than online. Pupils were particularly confident at recalling and using information which was used in several activities. For example, all pupils were comfortable using Zanes to support their analysis of Olympia; the Zanes were the focus of one of the questions pupils were given for the tour, were discussed as a class through dialogic talk as a follow-up activity, were illustrated in a lesson starter, and were mentioned when ‘walking’ past the treasuries. The use of the video game also seemed to encourage pupils to consider the space in terms of personal experience, helping them evaluate its impact on a visitor, reflected both in how pupils responded to questions as well as pupils’ own comments about why they find using the game helpful.

In future, additional time needs to be left for class discussions of the game and its benefits and drawbacks as a model. Moreover, the game needs to be used selectively. Assassin's Creed: Odyssey designers pay little attention to pediments and artwork on temples, which means that it is better not to overstress the use of the game at this point and to focus on more accurate models. All pupils were able to treat the game evaluatively with questions to prompt their thinking; however, for some pupils more prompts need to be given to model how they can express their thoughts not only verbally but also in writing.