As a Latin teacher, I think a lot about reading. Without texts I would not have a subject to teach, and the goal of many Latin programs (including my own) is teaching students to read Latin texts. I began my Latin teaching career while teaching the language to myself as well. The goal (both for myself and my students) was to read Latin confidently and fluidly, from left to right, processing the meaning of the words as my eye scanned the pages. Yet my good intentions were soon frustrated, and I was baffled by a problem which I soon realised was not unique to my situation: despite years of training, neither I nor my students could read Latin in a natural, fluid way. Furthermore, textbooks and colleagues seemed resigned to the view that such a goal was unrealistic or unobtainable. Best to treat language as a puzzle to be solved, or linguistic knot to be untangled, rather than a language expressing a message. Only the most intellectually gifted students continued in my ‘puzzle-solving’ course; consequently, my enrolment dropped off steeply after the second year. Looking for more help, I even implemented various ‘rules for reading’ and ‘reading strategies’ advocated by others, yet rather than improve student reading ability, I felt my curriculum begin to feel increasingly cluttered with activities and processes that stole away from my students the valuable time needed to interact with the language itself. It was not until I began investigating the field of Second Language Acquisition (hereafter SLA) that I discovered some simple, yet fundamental principles about language that helped explain my students’ struggles and helped me rethink language teaching in general.

SLA is a broad field lacking at present a single unifying theory. As VanPatten points out, it is more correct to discuss ‘theories’ of SLA (VanPatten, Reference VanPatten2014). Therefore, to narrow the focus for this article, I want to discuss a single issue: reading; more specifically, what researchers call ‘extensive’ reading. My purpose is to define extensive reading, show its close relationship to language acquisition, and finally to advocate for extensive reading practices in a Latin classroom specifically.

Two Readers

Two primary difficulties present in any discussion about reading in any language (classical or modern) are that (1) reading is a complex series of conscious and subconscious processes (Krashen, 2004) and (2) there exist many types of and uses for reading (Grabe, Reference Grabe2009). Like Proteus, a unified, specific definition of ‘reading’ can be difficult to pin down, as that elusive word can shift meanings subtly (and suddenly), sometimes in the same discussion. Broadly speaking, reading is ‘the construction of meaning from a printed or written message’ (Day & Bamford, Reference Day and Bamford1998). Yet people read in different ways and for different purposes and can quickly and often unconsciously slip between reading modes whenever necessary (Grabe, Reference Grabe2009).

Imagine two students reading the same text. Although they are both showing the outward signs of reading, they are in fact engaged into two entirely different activities. Student A reads quickly and naturally, moves her eyes from left to right, comprehends each sentence line after consecutive line, interprets vocabulary at sight, and despite this fluent performance may only be vaguely aware of the linguistic processes that she is using. She attends primarily to the message of the text. Student B may struggle with much of the same book; her eyes may move slowly over the text, scanning back and forth as she puzzles out sentences, ‘untangles’ the word order, and guesses at the meanings of a multitude of unknown words. Her attention is taken up with the mechanics of interpreting and decoding language, making it difficult for her to follow the message of the text as she reads. Student A reads the text extensively, while Student B reads intensively.

Extensive reading is reading with a focus on comprehension of a message. Extensive reading is the most common sort of reading; i.e., it is what people generally mean when they talk about reading. For example, most people (assuming they have the requisite proficiency in English) are reading this paragraph to understand the message and follow the discussion, not to analyse the use of language or the organisation of thought. I am not implying that the reader who is reading for meaning will never shift their attention to matters of language or style, nor am I arguing that reading intensively is not a legitimate way to approach a text under certain circumstances. Traditionally intensive reading is heavily favoured in Latin classrooms, to the point that extensive reading (i.e. fluent, easy reading) is regarded as unnecessary, impractical, or ineffective for language learning. However, there exists a large body of research that suggests that just the opposite may be true, and there is a strong case for including extensive reading in any language program.

Intensive vs. Extensive Reading

Extensive reading is the purpose for which most texts are written. Intensive reading is needed when there is an interruption in communication, for example when reading something beyond one's comfortable fluency or reading a text that is highly technical or poetic. Palmer, who first coined the terms intensive and extensive reading, described intensive reading as slowly studying the language and expressions of a text ‘referring at every moment to our dictionary and our grammar, comparing, analysing, translating, and retaining every expression that it contains’ (Palmer, 1921/1964). This reading process likely sounds familiar to anyone who has studied a classical language. Yet, while ‘intensive reading’ is technically a form of reading, it is often far from what people generally mean by the term. The intensive process that Palmer describes and the other ‘reading strategies’ advocated by others are essentially mechanisms for coping with a text that is too far beyond one's proficiency to read fluently (i.e., ‘extensively’) (Bailey, Reference Bailey2014). Most textbook reading passages assume ‘intensive’ reading. Ironically, many books labelled Latin readers or ‘reading method’ in reality provide students with very little material to read in the natural, ‘extensive’ sense. They treat Latin as an object of study not a vehicle for communication. Like people who have trained as bicycle mechanics, but have never ridden the vehicle for themselves, students trained to analyse and dissect the mechanisms of Latin would experience great trouble when then asked to hop on and take it for a ride themselves. Teachers cannot expect students trained in such a way to have the ability necessary to read extensively. Their training has been of another sort.

Language Learning vs. Language Acquisition

To understand what extensive reading is and how it is different from other types of reading, a distinction must first be made between two types of language learning, which researcher Stephen Krashen identifies as ‘learning’ versus ‘acquisition’ (Krashen, 1983). One way of looking at this distinction is to consider learning something ‘from the inside’ as opposed to learning ‘from the outside’. Learning a language ‘from the outside’ means examining the language as an artifact of study and analysis. This shares similarities with other content area subjects like Physics or History. The focus is on the language itself as a content material to be examined and explicitly learned. Communication in the language is a secondary consideration - if it is considered at all. The goal is to master a definite set of discrete information about the language's structure, vocabulary, grammar, and syntax. The learner is looking under the hood of the language and learning how all the various moving parts work together. This approach to language study makes heavy use of the learner's native language. Students typically demonstrate mastery of the material through translation from second language (L2) to the first (L1). A heavy emphasis is placed on rote memorisation of lists and paradigms. The goal of such an approach is accurate and rapid translation and philological analysis. Nearly all Latin language curricula approach the language in this way (including so-called ‘reading methods’). This is language learning, or ‘learning about language’ (Waring, 2014).

Alternatively, learning a language ‘from the inside’ considers the L2 a vehicle rather than an artifact. It involves understanding and interacting in the language to accomplish a purpose beyond language study per se. The learner is a participant in and active contributor to the language community - whether that means out among the native speakers or in a classroom context (VanPatten, Reference VanPatten2017). If a student's goal is reading Latin - picking up a text and constructing and interpreting meaning from the figures printed on the page - she is desiring a communicative act. By engaging in the act of listening to or reading messages that the student can easily understand, the student gradually develops an implicit understanding and fluency in the language, that allows them to then interpret increasingly complex messages, as well as begin to communicate messages of their own.

The process of language acquisition

So, how does this work?

How does a student develop the implicit knowledge necessary for fluent, extensive reading? SLA researcher Bill VanPatten would say that the student learning the language implicitly is developing a ‘mental representation’ of the language (hereafter MR), which someone studying the language from the outside would lack. The MR is the speaker's implicit language system (VanPatten, Reference VanPatten2010). The system is implicit because even a native speaker may not have an awareness of what is going on in their mind when they communicate in their native language, as the processes involved are both complex and largely subconscious. Stephen Krashen first clearly articulated the process by which a learner gains implicit knowledge of the language: by comprehending messages in the L2 (Krashen, 1983). Comprehended messages are the driving force behind increasing mental representation. This is the process of language acquisition.

Since it focuses on the comprehension of messages, extensive reading is an efficient way to build mental MR. As a cyclist learns to ride by riding, much evidence suggests that learners become better readers by reading (Krashen, 2004). This is true for reading both in the L1 and L2, as the processes are fundamentally the same. The difference is a language learner (especially one in the first couple of years of study) will have a smaller MR than a native speaker and may not read complex texts as easily as a native speaker.

Let us return to the two hypothetical readers. Ironically, Student A by reading effortlessly and pleasurably, by focusing on the text's meaning and getting ‘lost’ in the message of the book, is making more language acquisitional gains than Student B, who clearly appears to be doing more work. For Student A, the text is comprehensible, her mind is processing more messages. Student B spends most of her time struggling to either recall lexical items or decipher complex sentences that she is not yet skilled enough to read proficiently; Student B processes far fewer messages, and therefore her fluency gains are proportionally fewer, despite her hard work. To move beyond slow, laborious decoding and translation, she needs a greater implicit knowledge of the language (or MR). Student B needs a text better suited to her proficiency.

Free Voluntary ReadingFootnote 1

So how do teachers approach reading in the Latin classroom in a way that encourages students to read extensively? Stephen Krashen has proposed what he calls Free Voluntary Reading (or FVR). Other names for this activity also include ‘sustained silent reading,’ ‘self-selected reading’, or even simply recreational reading (Krashen, 2004). The idea behind FVR is simply that students make the most gains in literacy and language proficiency through reading texts that they can select for themselves. Students can read at their own pace and are free to explore topics and narratives that most appeal to them. In a second language context, students are free to choose texts that most align with their current proficiency. In the Power of Reading, Krashen has demonstrated the effectiveness of Free Voluntary Reading in classrooms all over the world. It is easy to see how such a practice could facilitate the implicit language acquisition necessary to build reading fluency. If students can select the type and difficulty of their texts, they are more likely to encounter messages that they are not only able to comprehend but are also willing to comprehend. The more messages that students comprehend, the more their implicit knowledge of the language (or mental representation) will develop. FVR facilitates acquisition.

Over the years I have built a Latin FVR library in my classroom, beginning with my own novellas as well as a few written by fellow Latin teachers. Recently, this collection has expanded to include nearly 40 titles, and continues to grow month by month with the release of new novellas. FVR began in my third-year Latin class (five to ten minutes of reading three times a week), but soon expanded into my first- and second-year classes, as simpler and more accessible Latin novellas were printed. As increasingly greater numbers of Latin teachers around the world are beginning to stock FVR libraries in their own classrooms, I thought it may be helpful to provide teachers with some guidelines for implementing FVR and for selecting (and creating) texts appropriate for their students.

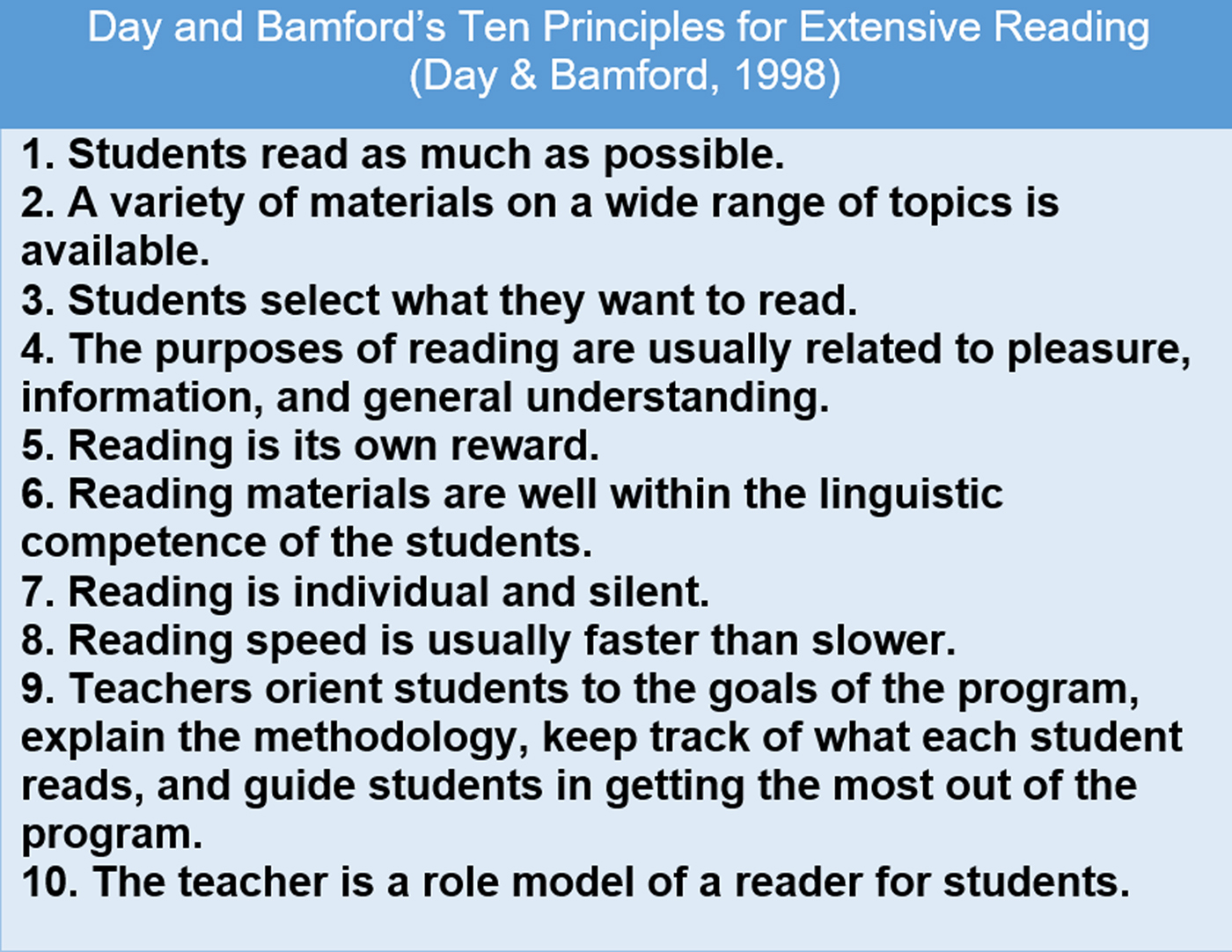

Day and Bamford, writing about extensive reading in second languages, have clearly articulated ‘Ten Principles for Extensive Reading’ which describe the conditions of texts and classroom environment that must be present to promote an extensive reading program like the one Krashen describes, especially among low-proficiency readers (e.g. students in their first years of language learning) (Day & Bamford, Reference Day and Bamford1998).

I have chosen to discuss four of these principles below most foundational to discuss using Latin novellas in a classroom setting. I will also use Day and Bamford's principles to describe how many of these new ‘comprehensible’ novellas and readers are different from many other Latin texts currently available for Latin students.

Principle 1: The texts are easy

Extensive reading must be easy. Some refer to it as ‘pleasure’ reading or ‘light’ reading (Krashen, 2004). The term ‘pleasure’ or ‘light’ can be misleading, because the purpose behind the reading may extend beyond mere pleasure or enjoyment (for example, reading an article in a scholarly journal for information on a topic). This activity, however, is still the act of extensive reading, as the reader is attending to the arguments and evidence presented, not the language itself. Extensive reading is the most natural use of a text.

For students to read a text extensively, that text must be below the students’ reading level. Day and Bamford call this ‘i minus 1’, where ‘I’ stands for the reader's current reading proficiency level, and the ‘1’ signifies a step below that level. This principal reflects the common practice of most readers (Day & Bamford, Reference Day and Bamford1998). When reading for pleasure or information, a reader gravitates towards a text that is clear and understandable to read. When reading a difficult text - for example a highly technical scholarly article for research - the intensive reading involved often creates an enormous amount of mental strain, as the mind is occupied with both decoding and deciphering jargon and technical language, while also trying to attend to the continuous thread of the argument. The reader must constantly redirect his attention between decoding and understanding. Reading is necessarily slower, and comprehension less complete. Therefore, both the quality and the quantity of comprehended messages is greatly diminished. Easier texts that sit well below the proficiency threshold demand less attention to the mechanics of the language; the reader can get lost in the text. Thus, the reader experiences one of reading's greatest pleasures: what some researchers call ‘flow’ (Csikszentmihalyi, Reference Csikszentmihalyi1990). Nation refers to this experience as ‘fluency practice’, exposing learners to easily-understood speech and texts comprised almost entirely of known vocabulary and structures. He further recommends dedicating 25% of classroom instructional time to such fluency practice (Nation, Reference Nation2013).

Figure 1. | Day and Bamford's Ten Principles for Extensive Reading.

Defining an ‘easy text’

‘Easy texts’ here will mean texts appropriate to novice, low-proficiency readers in the first two years or so of Latin study, which are also likely to be the highest-enrolled classes, and therefore the largest audience for FVR/extensive reading. While every program follows its own curriculum and pacing, principles drawn from reading research may help provide some general guidelines for selecting texts. Easy texts have limited vocabulary, straightforward and uncomplicated syntax, student-friendly aids for comprehension, and a compelling topic and/or plot.

Limited Vocabulary

The high density of unknown vocabulary is the primary barrier for a novice reader. If a reader struggles with recognising and understanding vocabulary, communication ceases between reader and text, and conscious attention is moved to deciphering the language, not the message. To read fluently and rapidly for comprehension, a reader must know 98% of the words or more (Nation, Reference Nation2013; Waring, Reference Waring and Cirocki2009). Grammatical structure and syntax factors less in determining comprehension of a text, meaning beginners can tolerate syntax beyond their acquisition when reading for comprehension (through contextual clues, cognates, the reader's familiarity with the subject matter, etc.) (Krashen, 1983). A high concentration of unknown vocabulary, however, will bring any reader to a halt. The amount of unknown vocabulary must be low for novice readers.

Straightforward and Uncomplicated Syntax

For novice readers syntax and clause length should be limited, but not necessarily grammatical features. Active and passive voice, participles, deponent verbs, and subjunctives may appear frequently, if the meaning is clear and subject concrete. The key is helping students process the language quickly and effortlessly. Readers process short clauses faster than longer clauses. Simplifying compounded sentences into shorter clauses helps the reader follow the message of the text and leads to the natural repetition of ideas and vocabulary which can be helpful to a learner. Also, reading a large quantity of shorter clauses does in fact prepare students for longer, more complex sentences. Cicero's longest and most tortuous periodic sentence is in its essence just a series of short phrases and clauses artfully arranged and eloquently expressed. As students’ proficiency (and MR) grow, they will process longer and longer clauses with increasing ease and accuracy and diminishing effort as their proficiency grows. It just takes a great deal of comprehended messages.

‘Un-sheltered Grammar’

‘Un-sheltered grammar’ simply means that the grammatical structures in a text are not necessarily pre-determined, nor do they follow a prescribed grammatical sequencing. There is no communicative reason for a text not to include manus because it is fourth declension, or loquitur because it is deponent; they are often delayed for reason of the systematic learning and practising of grammar. Roman authors do not limit themselves this way; they are communicating a message to an audience. An author writing to tell a good story may liberally use third declension verbs without fear that the audience has not yet ‘covered them’ in class; what concerns such an author is whether or not the story connects with and is comprehensible to the intended audience. Texts with unnaturally or artificially sheltered or sequenced grammar lack this communicative authenticity, even if they are otherwise stylistically and grammatically sound. Texts written by native speakers for native speakers are the best examples of authentic texts, because they were written to communicate a message and they adjust their style and tone to their audience. While many would define any text written for learners and/or by non-native speakers as ‘inauthentic’, for the sake of language acquisition, what matters more than who wrote the text is how the text is being used. Rather than asking if the text is authentic, a better consideration would be: ‘Is the text being used authentically; i.e., to communicate a message’ (Day & Bamford, Reference Day and Bamford1998).

Student-Friendly Comprehension Aids

Books written for novice readers need to provide comprehension aids in to establish meaning quickly and easily. Traditionally, graded readers and textbooks provide glossaries that use traditional dictionary entries: principal parts for verbs or declension and gender information for nouns, followed by various definitions. Such entries assume that the reader has mastered the discrete grammatical information need to decipher the terms they are seeking. Imagine a student looking up tulimus discovering the word is from tuli, the third principal part of the verb fero. The reader must then deduce that tulimus is in the perfect tense. Then after recalling both the -mus personal ending, meaning we’, and the tul- perfect tense stem, meaning ‘has carried’ or ‘carried’, this reader must finally conclude that tulimus must mean something like ‘we carried’ or ‘we brought’. And this of course assumes that the student somehow found his way to verb fero in the first place, rather than fruitlessly browsing the ‘T’ section. More helpful glossaries may provide such irregular forms with a note that says something like ‘see fero’, demanding yet more flipping from the student rather than answering their query. On the other hand, aids friendly to the novice reader include pictures, footnotes or marginal glosses, and/or expansive glossaries, including every inflected form of the word translated list as separate alphabetical entries, providing a full English equivalent. In such a glossary, the entry for tulimus might simply state: ‘we carried’. My point is not that students need not learn to use a Latin dictionary. Rather, one should not confuse the destination with the journey. The best use of traditional dictionary entries are language study and scholarship, not reading fluency development and language acquisition.

Compelling Topic or Plot

Student interest in a text is the key to extensive reading. The easiest way to motivate a reader is to give them something to read that they can understand and that is interesting to them. If a reader's interest in the text is strong enough, that reader may well choose more difficult books (e.g., ones that have a greater density of unknown vocabulary). Conversely, the simplest text may present great difficulty to a reader who has no interest or investment what they are reading.

Principle #2: A variety of reading material must be available

Since students in any given classroom will most likely read at varying levels of proficiency and possess a variety of interests, an FVR program ought to consist of a large pool of texts that reflect this diversity of skill and interest. While more and more accessible texts for Latin students are appearing (many self-published), the total amount is exceedingly small compared to other languages. Day and Bamford recommend a book per week of independent, extensive reading; currently, meeting that recommendation is far too difficult given the students simply need more easy texts in Latin, on a variety of topics (fiction and nonfiction). More available texts would allow students to better self-select texts based on their current proficiency.

Principle #3: Learners choose what they want to read.

In The Power of Reading, Krashen presents a vast amount of data supporting what he calls Free Volunteer Reading (FVR), defined broadly as ‘reading because you want to’ (Krashen, 2004). Students choose their own reading material with little to no traditional accountability attached (worksheets, book reports, etc.). Also, all forms of literature are acceptable for reading material, from novels to comic books. In Krashen's view, supported by Day and Bamford, students improve their reading by reading (Krashen, 2004). Since one purpose of extensive reading in a second language is to provide large amounts of comprehensible messages (to build the student's MR), books need not be sequenced or graded. Reading in the classroom should mirror the way readers outside the classroom use books. Students should let their interest and inclinations guide them. Students should be free to stop reading a book at any point and pick up another one.

Choice is a powerful motivator. As stated above, interest will eventually guide the student towards more complex texts, as their confidence and proficiency grow, in the same way that native language children over time tend to self-select more and more difficult books for themselves. To be truly effective, however, an FVR program first and foremost needs a library of texts from which students can choose. While indeed many ‘comprehensible’ novellas and readers have been published already, the work has only just begun. Authors are publishing texts at a steady trickle, when students need a deluge. In order to appeal to the diversity of student interest, a similarly diverse corpus of texts must be readily available. Scarcity of accessible texts is the largest obstacle for a Latin classroom's FVR program.

Principle #4: The purposes of reading are generally related to pleasure, information, and general understanding.

People typically read for pleasure, information, or understanding. This reflects how readers use texts assuming they freely choose their own texts. Extensive reading is simply reading for meaning, i.e., the most natural and common form of reading in the L1. Few learner texts in Latin (if any) exist with this form of reading as the primary goal.

With few exceptions, the material written for Latin students generally falls within a few limited categories. A textbook provides passages and practice, auxiliary readers provide additional reading material for a textbook program, and graded readers contain passages that begin simple and gradually grow in complexity. There are also many transitional readers on the market which attempt to bridge the gap between textbook passages and the authentic Latin literature that make up the traditional Latin curriculum. These books typically present a classical text intact or adapted with copious grammatical and lexical aids for the student, as well as cultural and historical background information essential for interpreting the text. All texts have a common goal: some form of intensive reading. Their aim is language study. The aids exist to assist students in deciphering a text that is cluttered with otherwise incomprehensible language. The reader must parse, translate, decode, and disentangle the language just to discover the meaning.

Comprehensible texts for language learners (like the novellas discussed above) should exist to communicate a message to a particular audience. Their ultimate purpose is to provide a novice reader with engaging material in order to facilitate acquisition. Ideally, the author did not select individual points of grammar or vocabulary around which to focus the narrative. The intended audience, the demands of the narrative, and the work's genre freely determine the vocabulary, grammar, and syntax of the book, rather than a predetermined syllabus. Such books by their nature tend to be more interesting and accessible to readers (Krashen, 2004). Not only should the text be simple enough that the reader can decode it quickly and effortlessly enough to attend to the message, but the text should present the reader with a reason to read it.

Selecting FVR/Extensive Readers: An overview of available material organised by levels

Below is a scheme I have devised for organising some of the currently available novellas. Three factors guide my organisation: number of word families, lexical density, and the amount and accessibility of vocabulary aids (footnote: an accessible vocabulary aid might be a footnote providing a clear English gloss, and/or a glossary that lists each inflected form of a word as a separate entry). As is clearly laid out in the previous section, the linguistic requirements of the text are not the only factor to consider when selecting texts. However, excessive vocabulary demands may be a novice reader's largest obstacle in extensive reading, and vocabulary count and density prevent a convenient and transparent standard by which to divide the available texts. The audience for this list is high school students (aged 14-18) reading Latin texts independently beginning in the second semester of Latin I (or first semester of Latin II) until their final semester of Latin IV.Footnote 2

Figure 2. | FVR novellas arranged by word count.

Though a recent phenomenon, the corpus of independently published Latin novellas continues to grow rapidly; doubtless by the time this article is published four or five more will have been added to their number. As an author of a few novellas myself, I am most gratified to see more and more authors providing a greater diversity of reading options; and I hope that many more volumes follow. However, as the above chart made plain to me even as I compiled it, there is a large dearth of intermediate works which can span the gap between the simplest texts aimed at near-beginners and the novellas which demand knowledge of increasingly greater amounts of vocabulary. Teachers using novellas to replace a textbook or to transition their intermediate students to Latin authors may find many of these more advanced novellas useful for that purpose; such novellas, however, may be less accessible as part of an extensive reading program, which I confine narrowly to Day and Bamford's guidelines.

In my own classroom, the results of Free Voluntary Reading have been remarkable enough that each year I have expanded the program and dedicated more classroom time to extended reading across all levels of Latin. In fact, many of the traditional Latin bugbears have all but vanished. For example, generally, my students read quickly and confidently, processing the Latin from left to right, without recourse to ‘reading strategies’ or ‘hunting for the verb’. They do not baulk at longer texts. They count their progress by pages rather than lines. When the Latin language is before them, they see neither a puzzle nor a knot to be untangled; they read expecting the Latin words to mean something. While the usual problems of student motivation and behaviour persist, each year my classes shift gradually closer to that ideal which I envisioned when I was just beginning as a Latin teacher: students reading the Latin language with confidence and skill. In fact, a further benefit of extensive reading has recently emerged: more and more students are progressing into the advanced levels. Due to student demand, this past year I have had to add a fourth year of Latin study (and soon may add a fifth). A great need still exists for more accessible texts on a greater variety of subjects; specifically, more interesting texts are needed with unique word counts under 180 words. According to Waring, a ‘fundamental mistake’ of language programs is to view extensive reading as somehow secondary or optional. In fact, he goes so far as to state:

‘Extensive reading (or listening) is the only way in which learners can get access to language at their own comfort level, read something they want to read, at the pace they feel comfortable with, which will allow them to meet the language enough times to pick up a sense of how the language fits together and to consolidate what they know. It is impossible for teachers to teach a “sense” of language. We do not have time, and it is not our job. It is the learners’ job to get that sense for themselves. This depth of knowledge of language must, and can only, be acquired through constant massive exposure. It is a massive task that requires massive amounts of reading and listening on top of our normal course book work’ (Waring, Reference Waring and Cirocki2009).

Since I incorporated extensive reading practices (including FVR) into my Latin classroom, I have experienced the joy of teaching students who have a deep, implicit knowledge of the language. They have a real Latin ‘sense’, and reading Latin is no longer a chore, or a puzzle soluble only by the linguistic or academic elites. Yet the work is not done; rather it has only begun. Some of my fourth-year students have read nearly all the books on the shelf and ask for more. My classroom FVR library eagerly awaits new volumes. The trickle of texts must become a flood.

Andrew has taught Latin for ten years at Hebron Christian Academy, in Dacula, GA. He holds a Master's Degree in Latin from the University of Georgia, and attends the University of Florida in pursuit of a PhD in Latin and Roman Studies. He is author of the Comprehensible Classics series of Latin novellas, aimed at novice and intermediate readers of Latin. To date, the series comprises seven volumes.