Part II

This study presents the results of research conducted by means of in-depth interviews within the framework of an undergraduate course on ancient Greek poetry taught at a Greek-speaking university. The research, which was carried out as part of a postgraduate programme for an MSc in Digital Education, sought to investigate students’ responses to and experience of a number of activities informed by game principles and designed with a view to engendering playfulness. I refer to this form of assessment as ‘Game-Informed Playful Assessment’ (GIPA). My research question was the following: how is GIPA received by students enrolled on an ancient Greek poetry course at a Greek-speaking university? Μy main objectives were to investigate:

• whether students had experienced other innovative forms of assessment before.

• The differences that students would identify between GIPA and traditional forms of assessment.

• how students would articulate and describe their experience with GIPA in terms of enjoyment and learning.

It should be stressed from the outset that the results presented here continue and complement a previous article, published in the Journal of Classics Teaching, Volume 21, Issue 41, Spring 2020, pp. 42–5. In that article I offer an extended literature review on current theories regarding assessment, the use of games and game principles in the educational process, and the notion of playfulness. I also lay out my rationale for designing the GIPA, providing important information about my field of study. This background information is essential for a clearer and better appreciation of what follows; consequently, Parts I and II should be read in tandem.

Methodology, Epistemology, Participants

For the purposes of my research I adopted a qualitative approach, which allowed scope for a deeper understanding of students’ perceptions of their learning experience (Scotland, Reference Scotland2012). The design strategy best suited to such a study was phenomenology, an approach that places experience in the spotlight, in order to gain insight into people's motivations, feelings, thoughts and actions, and to obtain comprehensive and accurate descriptions that portray the essence of lived experience (Giorgi, Reference Giorgi1997; Moustakas, Reference Moustakas1994).

I decided to gather my data through in-depth individual interviews (Mears, Reference Mears, Arthur, Waring, Coe and Hedges2012), a method widely used in phenomenological research (Giorgi, Reference Giorgi2009; Bloor & Wood, Reference Bloor and Wood2006). Following the practices of phenomenological research, the participants were chosen randomly (Hycner, Reference Hycner1985; Englander, Reference Englander2012) provided that they were willing to be interviewed, they had been involved in all four activities, and had attended at least 50% of the lectures. Since what really matters in phenomenological research is not the sample size but the deeper meaning of one's experience of an event (Hycner, Reference Hycner1985), I kept my sample relatively small (ten students), in order to be able to conduct a more in-depth analysis of my data. Table 1 outlines the demographics of the students that participated in the research. To ensure confidentiality and anonymity, the identities of all participants have been concealed.

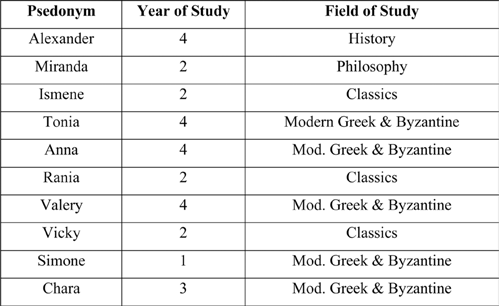

Table 1: Demographics of Interviewees

Data Generation and Presentation of Data

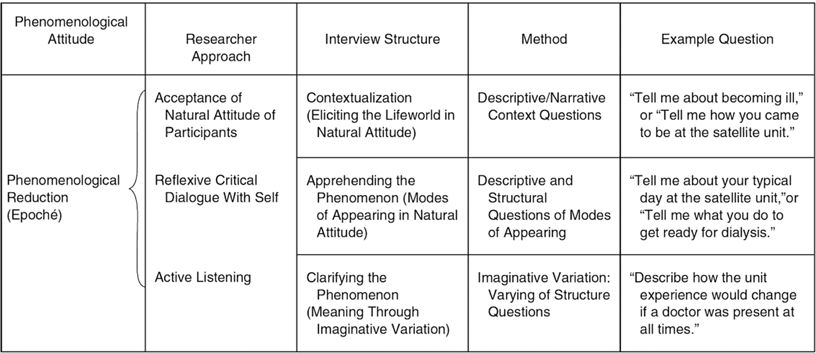

The interview questions were kept quite generic, in order to allow interviewees to freely express themselves and touch upon issues that mattered to them. At the same time, the generic nature of the questions allowed me scope to probe potentially promising remarks that might crop up during the discussion. For the formulation of the questions I adopted the model proposed by Bevan (Reference Bevan2014), according to whom a more structured phenomenological approach to interviewing enables richer and more holistic descriptions. On these grounds, Bevan suggests that a phenomenological interview should contain questions that enable the researcher to contextualise the experience, and to apprehend and clarify the phenomenon under investigation (Table 2).

Drawing on Bevan's model, I designed the following five interview questions:

1. Could you tell me how you decided to study Greek philology, and describe your experience of studying ancient Greek so far?

2. This semester, within the framework of the archaic Greek lyric course, you were asked to perform a number of small-scale activities weighted at 20% of your final grade. Can you recall your thoughts and feelings: a) upon the announcement of the activities; b) during the implementation of the activities?

3. Can you describe your experience of each activity separately?

4. Can you describe one thing (thought, sensation, feeling) that you remember especially vividly about the experience?

5. Can you describe how your engagement with the archaic Greek lyric poets might be different if the activities were replaced with a different assessment method?

Bearing in mind that all students had attended many hours of ancient Greek at both school and university, my first question sought to contextualise the participants’ experience by exploring their feelings towards ancient Greek. Through my second and fourth questions I sought to apprehend how the GIPA was experienced as a whole. The third question aimed to elicit an in-depth description of how students had experienced each activity separately. For the purposes of further clarity in the presentation of the phenomenon, my fifth main question was designed to encourage imaginative variations, in order to explore students’ experience.

Because of the time lapse between the implementation of the activities and the interview, I also deemed it essential to provide brief reminders of each activity, so that students could retrieve the experience more easily. Therefore, the third question also consisted of the following subsidiary questions:

1. For the first activity, you were asked to work in teams and collaborate in Blackboard. You were asked to go through Archilochus’ poetry, trace its main features and write a poem about Archilochus using a particular metre. You were also asked to associate Archilochus’ poetry with a contemporary painting. Can you describe your feelings and thoughts while performing this activity?

2. For the second activity you and your team were given a scenario and were asked to discuss Archilochus’ fragment 128. You were also asked to take photos or create a video that would illuminate the poem under investigation. Can you describe your experience during this activity?

3. For the third activity, you were asked to comment on the first two assignments of a different team. How did you experience this activity?

4. For the fourth activity, you were asked to work in couples or alone and compose a short text where you addressed a lyric poet adopting the perspective of a millennial living in Greece/Cyprus in 2018. You were also asked to accompany your text with a photo and a snappy caption. You were informed that the ten best assignments would be printed out as A3 size posters and would be exhibited as part of a public event. How did you experience this activity?

Table 2: Structure of Phenomenological Interviews (Reproduced from Bevan Reference Bevan2014)

All the interviewees attended a preliminary meeting where we reviewed the ethical considerations and they completed the consent forms (BERA, 2018). During this meeting participants were also asked to go through the research questions, in order to have time to ponder on their experience before the interview. A possible objection to this practice might be that such reflection ‘spoils’ the participants’ spontaneous, pre-reflective responses and leads them to make their own interpretations of the experience. A counter-argument is that foreknowledge of the research questions may enable interviewees to provide a richer description by retrieving more details about their feelings, memories, thoughts and sensations regarding an experience. As Englander points out, ‘The goal of the later data analysis is to describe the psychological meaning and this also includes describing the psychological meaning of the participants’ self-interpretations’ (Englander, Reference Englander2012, p.27). Besides, we should not forget that the narration of a past event, even when this is supposed to be done spontaneously, is not de facto more trustworthy, sincere or authentic, because the past is always understood through the lens of the present. In recollection we always have an overview of the whole and know the ending; hence our narration is, in one way or the other, informed by that ending (Ricoeur, Reference Ricoeur1980).

Upon completion of the interviews the transcription of the recordings posed one major challenge. Whether we like it or not, transcription is an interpretative act: the transcriber has to make several assumptions during the transcription and a great deal of the authenticity of the data is compromised—albeit unconsciously—through one's cultural-linguistic filters (Ross, Reference Ross2010). Given that the interviews were conducted in modern Greek, the students’ native language, the transcription was also done in modern Greek; I only translated into English those passages which I chose for verbatim quotation. Although I paid a great deal of attention to issues of accuracy, I am aware that my transcriptions are not exact replicas of what was said during the interviews. Indeed, on some occasions I had to make difficult decisions as to what the students may have meant, in order to be able to provide a translation.

The interviews were illuminating in many respects and raised some interesting and intriguing questions. Due to limitations of space, here I concentrate on the most important issues that came up, illustrating them with ample evidence, so as to both show the richness of the experience and allow the students’ voices to be heard. The findings are presented by question. Following pure phenomenology, I have attempted to simply describe my data, even though an interpretative element has also been added to the presentation.

Ancient Greek and the Students’ Emotional Baggage

Students’ responses to the first question (Could you tell me how you decided to study Greek philology, and describe your experience of studying ancient Greek so far?) varied. Five students characterised their relationship with ancient Greek as good, emphasising that they had achieved high marks in this subject at secondary school. The rest of the students commented that ancient Greek was not one of their favourite subjects, mainly because of the conservative way ancient Greek is still taught. Simone and Miranda explained that their experience had improved at university, because in addition to grammar and syntax attention was also paid to interpretation. Anna, who claimed to have received one of the highest marks in the subject in the national entry exams, stated that her experience of ancient Greek at university had been worse, because she had expected that her teachers would adopt an alternative mode of teaching and would make more extensive use of technology.

Innovative Assessment and Students’ Emotions

Responding to the second question (Can you recall your thoughts and feelings: a) upon the announcement of the activities; b) during the implementation of the activities?), six students reported that they had experienced strong negative feelings including anxiety, confusion, insecurity, stress, perplexity and fear. These students identified two main sources of stress: the fact that they were not accustomed to this kind of assessment and their inexperience in working with groups. Miranda's response is illuminating:

Well… my reaction was not good [laughing]. So… my first concern had to do with the group work. I said: gosh! How will the teams be formed? Who shall I work with? There are several of my peers who I do not know… What if the collaboration doesn't work? What will happen then? And what if I am the one who cannot collaborate? This was a problem… My second concern had to do with the fact that we had to be creative… Having spent so many years practising rote memorisation, it is veeery hard to be asked to be creative again in just one semester… To cultivate, in any case, this kind of thinking…

Rania spotlighted the novelty of the assessment:

I hated you for five minutes, you know. For sure [giggling]! I was so stressed! These kinds of thing stress me out… They stress me out because we haven't done anything similar in the past. It was something entirely alien [in Greek, xeno]… We are not used to it… Something entirely alien… We had none of this kind of assessment in our other courses… Alien and utterly new.

Chara further specified that she had not liked the idea, because she felt that this kind of activity would not prepare her for the final written exam.

When asked if their initial feelings had remained the same throughout the activities, all six students reported that there had been a radical shift. As Ismene observed, ‘From the first activity the anxiety gradually developed into creative stress, critical thinking and creativity’. Five of the students credited this change of feeling to the good collaboration they had with their teams from the very beginning.

Two of the ten students remarked that, on hearing about the activities, they had experienced mixed feelings. Alexander stated that he had been caught by surprise, which he defined as both positive and negative; Tonia noted that she had felt both stress and curiosity. Tonia also commented that she had been surprised to hear that the activities would be graded and count as 20% of the final evaluation.

Finally, Vicky and Anna reported that their reaction had ultimately been positive. Anna saw the innovative assessment as a challenge:

Well… when a teacher tells you that you won't have a midterm, you take it as a good thing… Of course, after you explained how this would work, it was not that easy… but it was more creative. But… given that this was the only course that was creative—in the other courses nobody has never asked us to do anything similar—most of the students I spoke with were stressed … because they have learnt—this also applies to me—only to write academic essays… But… I mean… we keep complaining about the midterms, and then, when a teacher suggests something new, we complain again… Αt least we should give it a try!

Engagement, Motivation and Flow

The third question (Can you describe your experience of each activity separately?) brought several issues to the fore.

Activity 1: Playfulness and Situated Learning

The great majority of students reported that the composition of the poem had been by far the most difficult task. To quote Miranda:

We had difficulties at first. Especially with the writing of the poem… And… I remember that after we submitted the first assignment, I kept thinking about it and realised that we did something wrong with the poem… We didn't fully understand how we were supposed to write it… I remember us trying to put something together… we were counting syllables, we were thinking of the metre… It was nice… It was very nice… All you needed was to be creative… And it was collaborative work; everybody had to contribute…

Three students underlined the joy and satisfaction they had shared with their team upon completing the activity. Rania's account is illuminating:

Rania: I remember that at the beginning it seemed impossible to us!

Interviewer: What exactly?

Rania: Especially the idea of the poem…We had in mind that we must follow the instructions, in order to get it right, be right… the requirement that all the even syllables had to be accented stressed us out! And it stressed us out primarily because two of us were living here, the other two in other cities… therefore, we Skyped in the evenings. For the first three or four days we were Skyping and sitting there for hours—just staring at each other trying to make sense… In vain! And then we started taking notes and, all of a sudden, it was going well… I remember our screaming and how glad we were, when we finished the very first verse [giggling]. We were so excited! Just the first line! And then the rest just followed… it was also the message that we wanted to communicate… It was good that we hadn't interpreted the poems in class… We had more freedom… That helped a lot… And at the end it was such a relief! We couldn't believe that we had written all that. I don't know how it came out, but we liked it very much. It was ours!

Students found the association of Archilochus’ poetry with a painting easier. Rania noted that, without their realising it, the association had also prompted them to think about art:

…without realising it, you're associating entirely different things. And, while, let's say, my intention is to work with a single text… in this way I am also prompted to deal with art…and without realising it, I get into the process of analysing art… That's why I think that we gained a lot. Because without realising it, we were also dealing with art.

Miranda commented on the feeling of surprise that she experienced while working on the association:

To be honest, I would never have thought about it… But really… when you, hmm, get into the process of making the association, indeed, you are surprised yourself. When you realise that it is, indeed, possible for me to do this and that, indeed, it is not something that difficult… to be… to be creative… to be able to think of other things than what other people tell you is right…. It is, indeed, great fun and, indeed, it can help you… I mean… in our attempt to analyse the colours, the posture of the figures in the painting we were working with… indeed, so many ideas sprang to mind… and this is something we do not often have the opportunity to do.

Activity 2: Authenticity and Playfulness

All the students described the second activity as an authentic task. They commented that, in adopting the identity of a secondary-school teacher, they had felt that they were applying their knowledge to a real-world challenge which they were probably going to face in the future. To quote Anna:

This was much better than the first assignment, because we had to get into the role of a teacher—which is what we are studying for… And the photo… OK, the photo gave us a hard time, but finally we thought of something that, if one was just seeing it on the photo without us explaining it, one would say that it is irrelevant. […] For instance, what we did with the photo… I would like, if I went to a class where students would have no idea of a poet, to talk to them about this poet in this way. I would not have thought of it before…

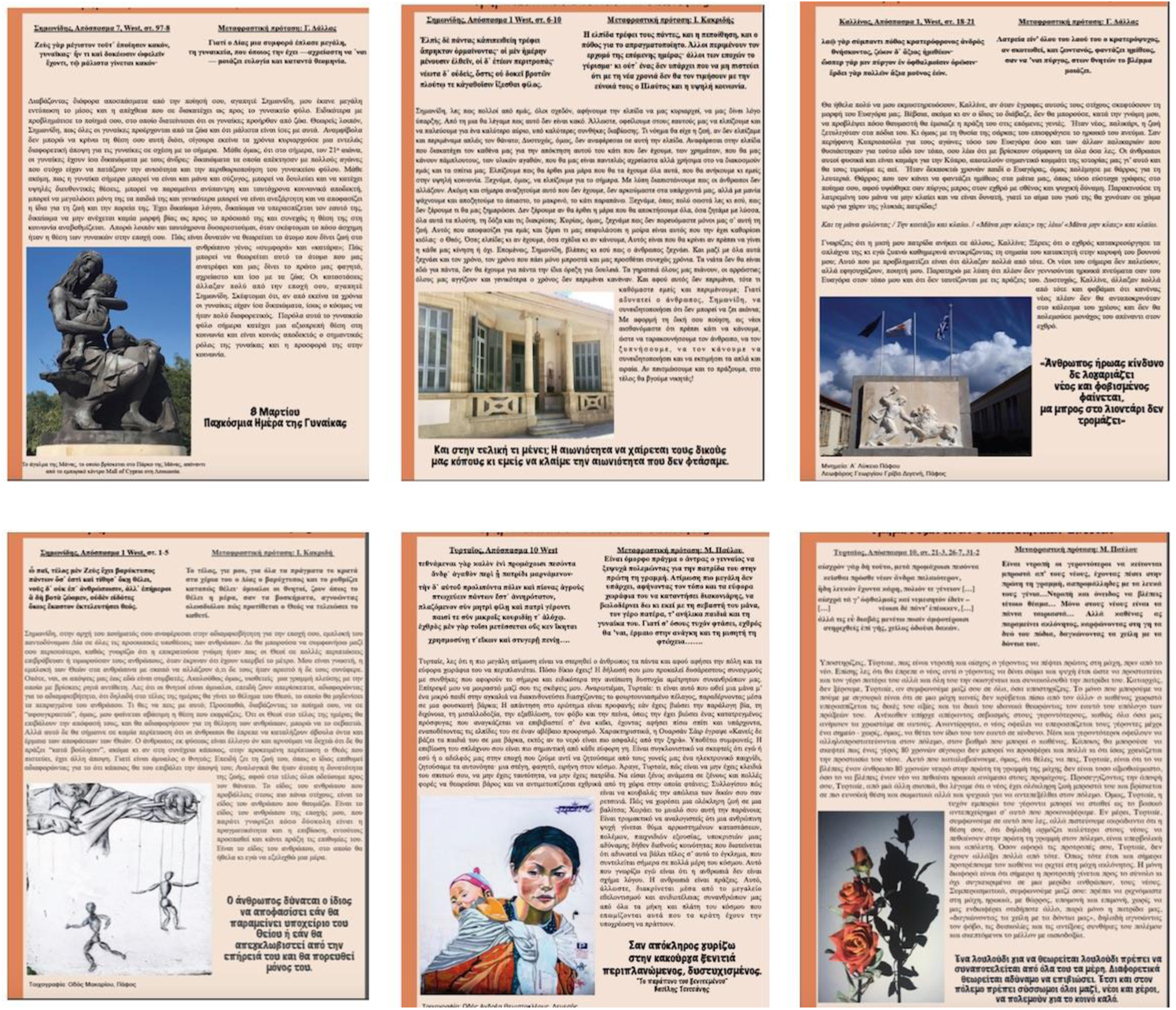

Figure 1. Some of the photos taken by students for Activity 2.

Many students reported that the restriction that they had to take their photos on campus had encouraged them to pay attention to aspects of the university environment that they had not previously noticed. As Alexander noted, although initially he and his team had been put off by this limitation, after they had started looking around, they realised that they had several choices and that the limitation was necessary for the ‘awakening’ of their creativity. Simone described how her team had decided to completely rewrite the finished assignment for the second activity, because they had not felt entirely satisfied with the first photo they had taken and commented on. Tonia described how she had taken the photo chosen by her team during a moment of leisure:

Personally I spend too much time at the university library… I stay until late in the evening… I remember that one evening I went downstairs to take a break. When I looked up for a moment, I saw a peer passing by… While he was walking, he looked like a shadow, because it was dark… I immediately took a photo with my smartphone…While reading the poem I felt (and my team agreed) that I wanted to compare humanity to a shadow that, despite difficulties, moves on and struggles to maintain a balance… a ‘measure’…

Although for the second activity students had been given the opportunity to illustrate Archilochus’ fragment using either photos or video, only one of the 15 teams prepared a video. Rania, a member of that team, explained that one of the other team members had a friend whose sister (of the students’ own age) had been through a difficult illness. Since one of the points raised by Archilochus 128 is that humans should not succumb to difficulties, the group decided to contact the young woman and ask her to share her experience with them and be video-recorded. When she consented, the students had to deal with another obstacle: the limitation that all videos (and photos) had to be made on university campus. The team solved the problem by having a conversation with the young woman via Skype on university premises. Rania singled out the emotional impact the activity had on her:

This was an experience that I have never had before… We thought that only if you show to lyceum students something from current events, you could capture their attention… I was sure… even before your feedback, that the outcome was very good, very good… in the sense that it was something unique… I myself was feeling very moved… From the moment we talked with the girl and she explained to us what she went through… how she managed… she went abroad alone… I was so moved… The moment we decided to include her story in our assignment, we said that it was worth doing, regardless of the result. We didn't care about how it would be assessed… how this…because we knew that we had included something good… Inside I knew that it was something good. I pay attention to my grades but not this time… I do not know why…

Activity 3: Peer Assessment

Students reported that they had never been asked to assess their peers before. Alexander noted that, as an Erasmus student in Germany, he had noticed that the practice of peer assessment was well established. He contrasted this with Greece and Cyprus, where he felt peer assessment was still ‘taboo’. Eight students evaluated the activity as difficult, because they were anxious to use the right wording, for fear of offending or hurting the feelings of their peers. As a result, a lot of time had been spent on how to articulate and phrase their feedback. Ismene's account is illuminating, not least because it also provides a list of the features that she and her team considered ‘good feedback’:

To assess the assignment of another team… this means that automatically you get into the process of making judgements… this happens in our everyday life as well. People judge us on what we say, on what we do. So, hmm… we had to be very careful about what to say and how to say it. To be precise and… back up our comments…that is to be clear… not to write generalities… We also pondered on our own assignments and on how the other teams would judge us… So, we agreed that we should evaluate them in an objective way, as we would like our own assignment to be evaluated.

Tonia stated that she and her team had felt weird and a bit puzzled, because they did not feel they were in position to fully understand and appreciate what the other teams had written. Three other students drew attention to the fact that this process enabled them to rethink their own assignments and even identify some of their own mistakes. Alexander also argued that the process had helped them to get into the teacher's head and understand how teachers think, while grading assignments. Finally, one student claimed that this kind of assessment enhanced critical thinking. Half of the students observed that the whole process would have been different if they had not worked on the same assignments themselves. As Vicky pointed out, it was interesting and revealing to see that other students approached the same topics in such different and diverse ways.

Activity 4: Autonomy and Agency

All the students commented on the strong feelings they had experienced, while addressing the lyric poets in the second person singular. Alexander noted that the use of the second person helped them to ‘resurrect’ the lyric poets, while Chara stressed that the abandonment of the third person singular—typically used in academic essays—made her feel that she could express herself freely. The great majority of students also emphasised that their ‘dialogue’ with the lyric poets had enabled them to further appreciate the timeless and universal value of archaic lyric poetry. As Vicky commented:

I did not believe that we could use such an old poem to talk about contemporary things… Honestly, I did not believe this… I would never think of this…

The notions of autonomy and agency also came to the fore. Simone explained that the opportunity to talk to a lyric poet from the perspective of a young person of her own age had ‘liberated’ her from her identity as a student and philologist-to-be, and had allowed her not only to speak with her own voice—as a 20-year-old living in a Greek-speaking country—about several issues that concerned her, but also to send a message. A similar point was made by Vicky, who confessed that she had been perplexed about which fragment to choose for her assignment:

Initially I worked on a fragment of Archilochus [the student here confuses Archilochus with Tyrtaeus] which I felt that I didn't really understand when we went through it in class. I didn't get the gist… it was about youth… dead bodies… war… sacrifice for one's native country… I believe that we ought to love our native country… Gradually I felt that the message I wanted to communicate could be better illustrated through a different poem…

The emotional attachment described by Vicky is best illustrated by Ismene's response:

Ismene: I decided to deal with the issue of refugees. I wanted to raise an ethical question at the end…I dedicated too much time because I wanted to use the most appropriate words… It was difficult for me… Hmm… But enjoyable… So many ideas squeezed into a condensed text… But at the end they led somewhere… They sent a message…

Interviewer: How was it to use an archaic poet to discuss contemporary issues?

Ismene: It is as if… it is as if… Tyrtaeus was living now and I was living back then… I found it very interesting… I am thinking that I could make similar associations with other poets as well…

Interviewer: Your photo was of street art….

Ismene: Yes… Actually, I was sceptical about this… This street art represents refugees, but contemporary refugees… And street art is also very often criticised… I was sceptical… Hmm… I would never have imagined that I could put down my own thoughts and create something so good… By reading it again and again and again I learned it by heart… [giggling].

Interviewer: How do you feel about it?

Ismene: I feel proud… Whenever I read it—because I still read it—I think that when other people read it, hmm, they will get my point, I will provoke feelings in them… I already asked my peers whether they read it, and I realise that it had an impact on them.

It should be noted that, when students were prompted to comment on the implications for them of the prospect to have their work publicly displayed, none of them reported any such implications. However, students whose work had been chosen for exhibition remarked that they had experienced feelings of pride and satisfaction.

Collaboration

Students reported that they had not worked in groups before. However, all spoke favourably about this experience, highlighting the advantages of being able to exchange ideas, persuade others through argumentation and learn with and from others. As Vicky put it, ‘With others we think alternatively’. Many students acknowledged that collaboration also involved challenges and that their experience would have been entirely different if their team had been dysfunctional. Chara referred to one such team, pointing out that some of her friends had had a hard time collaborating with their team members. Four students stated that their collaboration with others had had an impact on their character and skills, helping them to become more receptive to other ideas, to learn to compromise and to accept, as Chara reported, ‘…that occasionally others may have better ideas’. Chara also said that teamwork had made her realise that she had leadership and organisational skills, while Alexander highlighted the ability to collaborate with others as a significant lifelong skill. With regard to team dynamics Rania emphasised that collaboration with the same team for the first three activities had been conducive to her bonding with other team members. She juxtaposed this practice against that adopted ‘…in some foreign-language courses…’, where groups are formed randomly and only for the duration of a single class. She compared such episodic teamwork to ‘children's play’ (in Greek, paichnidaki).

Even though students were encouraged to use the VLE Blackboard for their discussions, the great majority did not follow this recommendation. Indeed, seven students stated that they had not even bothered to learn how the discussion forum worked. Since they either had never used Blackboard before or had used it merely for downloading course material, they deemed it more convenient to exchange ideas and share their material (photos and drafts) through Facebook and Skype. The majority of students reported that they had mostly communicated face-to-face, either on campus or in nearby cafés. Two students, whose teams had used Blackboard for a couple of weeks, stressed that they had found it useful to receive immediate feedback from me, as this had helped them to stay on track and feel more secure. Nevertheless, eventually they too had had to abandon Blackboard, because not all members of their team used the platform regularly, and because Blackboard did not allow synchronicity. Rania reported that her team had not used Blackboard because their discussions were great fun and they thought it would not be very appropriate for me, as the facilitator, to read their comments, which were not very ‘academic’.

Notably, while all the students acknowledged the benefits of efficient teamwork, half of them preferred to work on their own for Activity 4, stressing the full agency this gave them:

For the fourth assignment I worked on my own. This assignment was the best of all; it had the most interest and was something entirely mine. (Tonia)

We decided to work alone because we were five in our group, and if we had worked in couples one would have had to be left on their own… But in this way I felt that my own voice could also be heard… my own opinion. (Ismene)

Describing the GIPA in One Word

When answering the fourth question (Can you describe one thing (thought, sensation, feeling) that you remember especially vividly about the experience?), four students adopted a holistic perspective, contrasting their negative initial feelings with their subsequent positive feelings:

What I take from this course… one thought… a lesson… I would rather say… that we should never criticise something before experiencing it and trying it out… I will always remember how I felt when you announced that we would work in groups and how much I enjoyed it at the end… It really helped me to become more communicative… more creative… I really like it! I did not expect it to be like this… It was something amazing! I think that this is what I will always remember… (Miranda)

What I remember is the stress… but… but also the satisfaction, the fact that after the activities I feel that I have developed – in inverted commas – in terms of my thinking, my creativity, my ideas… in being able to think of different ideas and choose one, instead of thinking of one idea and write it down… simply to typically develop an idea. (Valery)

The rest of the students focused on the positive feelings they had experienced while working on the activities, particularly the activities that had made the greatest impression on them. As Anna put it:

What is left from all this is the creativity… This was the only course that was so creative… I am not just saying this. It is true. In no other course did they allow us to do something creative: talk to a poet, take a photo… I remember the other students watching me walking around campus with a digital camera in my hand… [giggling]. All this was so interesting!

In addition to the noun ‘creativity’ and the adjectives ‘creative’, ‘interesting’ and ‘amazing’ employed in the above quotations, when describing their experience students also used the terms ‘joy’, ‘pleasure’ and ‘critical thinking’. Most also reported having experienced some kind of emotional investment in the tasks (especially with regard to Activities 2 and 4). Vicky and Rania described the experience as ‘different’:

Different… For me what is different is good… it has no negative connotations. It is a good thing. It is nice to get out of this thing inside which others have put you for so many years now… (Vicky)

In my view the whole idea… the assignments, the teamwork… gave us the opportunity to work with the texts in a different way. Personally, I like rote memorisation [in Greek papagalia], but when it comes to the ancient Greek poets, to… I think that the way in which we worked left us more things… I believe that we learnt more… I believe that in this way we he had more interest in the ancient Greek texts… I believe that the course achieved this. (Rania)

Assessment for Learning versus Assessment of Learning

Responding to the fifth question (Can you describe how your engagement with the archaic Greek lyric poets might be different if the activities were replaced with a different assessment method?), all the students identified the ‘different assessment method’ with the traditional midterm written exam. Chara mentioned oral exams as another possible alternative. Notably, all the students described midterms in depreciatory terms, pointing out that the knowledge gained by studying for a midterm is retained for only a short period of time, because it is the product of rote memorisation. When describing midterms, students used terms such as ‘boring’ and ‘trivial’, pointing out that this kind of assessment requires specific answers, allowing no scope for one's personal view. Alexander raised the issue of diversity, arguing that midterms and final exams assess very specific skills, thus overlooking the fact that different students have different skills. Simone outlined the ‘strategy’ for successfully tackling a midterm:

If we had a midterm exam, we would learn a few things but we wouldn't remember them forever. It would be as we do now: we study, we do the exam, and when we leave, we forget… It was much more helpful than a mere midterm exam… In a midterm you learn the most important things, but you don't retain them, because you just read them superficially… and then everything is gone. You do not do research… if you do some research on a text, you will remember things… when you are asked to do something with a text, you return, you read it, you write, then you return again, you write, you return again… In this way you retain more things. While for the midterm, you can guess what it's going to be about… you will only read this stuff… and then everything will disappear!

In explaining how the GIPA had differed from a midterm, Vicky emphasised the control she had felt over the four activities:

A midterm exam would seem more natural, because this is what I have learnt so far. Others have put me into this mode of thinking and I had the impression that this was helpful. But now I understand that I have gained much more through these activities… I mean, I was involved with things that I wouldn't have been if I had only had to memorise some information. First of all, I would not have gained some of the knowledge I have now… And I would not have been hands-on with the material. I would merely have learnt something as the facilitator taught it. I would not have put myself into all this… Honestly, I did like it a lot!

Discussion of Findings

The interviews foregrounded a number of noteworthy and thought-provoking findings. Some of the views expressed by students were expected and are supported in the literature. Some of the issues touched upon, however, have not previously received adequate attention. In this section I selectively refer to and discuss some of the issues that I deem the most important.

Game-Informed Learning, Gamefulness and Playfulness

Even though the four activities were informed by game principles, none of the students used the terms ‘play’ or ‘game’ (in Greek both meanings are expressed by the word paichnidi) to describe their experience. While this might be mere coincidence, it may also indicate that students did not perceive the activities as a game/play. This is reasonable, considering that my design was game-informed, not game-based, and that I did not use game mechanics (e.g. achievement points, badges or leader boards) that might have added a game veneer to the activities. Another hypothesis is that students might have felt that defining the activities as a game/play would be incongruent with the seriousness of the tasks. This remark might find support in Rania's use of the term paichnidaki (‘children's play’)Footnote 2 to refer to an activity that was not deemed serious enough.

Students did not use the terms ‘playful’ or ‘playfulness’ either. Although this might also be a coincidence, it should be taken into account that in modern Greek the adjective ‘playful’ (paichniodes) is not as widely or commonly used as in English. In fact, the adjective ‘creative’, which cropped up many times during the interviews, is often used as a synonym. It might have been worth pursuing this issue further during the interviews, since the perception of something in a particular way nurtures certain expectations that can affect how one treats one's material (the ‘subject-expectancy effect’ (Supino, Reference Supino, Supino and Borer2012)). Following from this, students may find it more legitimate to ‘play’ with their material if they are explicitly told that the design of a course is underpinned by game principles or if they are asked to approach an assignment in a playful way. To be sure, even though the four activities were designed to foster playfulness, students’ preoccupation with ‘being right’ and ‘getting things right’ reveals that they need more support to adopt a playful attitude and dare to problematise (in clever and playful ways) even the rules and dogmas of correctness. It is important for students to realise that playfulness and seriousness are not mutually exclusive concepts but can and should go hand in hand (Skilbeck, Reference Skilbeck2017). As Plato succinctly put it in the Sixth Epistle, and as his dialogues manifestly exemplify, seriousness and playfulness are sisters that complement each other.Footnote 3

Innovative Assessment and Emotions

The feelings experienced by students upon the announcement of the innovative assessment during the first lecture call for particular attention. Taking into account student dissatisfaction with summative assessment, one would expect students to have welcomed the proposed alternative mode of assessment and to have experienced positive feelings, such as excitement and curiosity. The initial discomfort and stress experienced by the great majority of students clearly demonstrates that the introduction of a new kind of assessment—no matter how exciting this might seem to the facilitator—can provoke strong negative feelings such as anxiety, stress, uncertainty, even fear. This observation supports the thesis that new kinds of assessment may be risky and engender student distress and discomfort (McDowell & Sambell, Reference McDowell and Sambell1999; Bevitt, Reference Bevitt2015; Carless, Reference Carless, Carless, Bridges, Ka Yuk Chan and Glofcheski2017). As Gibbs (Reference Gibbs, Bryan and Clegg2006, p.20) points out, students are ‘instinctively wary of approaches with which they are not familiar or that might be more demanding… [and] unhappy about assessment methods where the outcomes might be less predictable’. Consequently, students’ dissatisfaction with current methods of assessment does not entail that they will readily embrace innovative assessment, even though it might point to their readiness to do so. No matter how exciting it may seem to the facilitator, innovative assessment, like all things new, needs to be scaffolded and supported (Vygotsky, Reference Vygotsky1978; Carless & Zhou, Reference Carless and Zhou2016). It might have helped, for instance, if students had had access to the course handbook, and therefore to the method of assessment, prior to the first lecture. Likewise, more peer assessment tasks in class might have alleviated the mixed feelings experienced by students with regards to peer assessment activities (Segers & Dochy, Reference Segers and Dochy2001).

Figure 2. Some of the posters that were displayed at a public event

Particular mention should be made here of ‘surprise’, the feeling one experiences when one expected things to be different, which was often mentioned by students in relation to the feelings they experienced while working on the various tasks. Surprise can have both negative and positive results, depending on whether one deals with it actively or passively (Hunzinger, Reference Hunzinger, Destrée and Murray2015). Even though surprise has not been examined in relation to GBL and GIL, it calls for further investigation, not least because of its association with the notions of ‘playfulness’ and learning. De Koven (Reference De Koven2017) defines playfulness as ‘an openness to surprise’, while, as noted in Part I of this study, in the Theaetetus Plato portrays the philosopher—and by extension anyone who pursues knowledge—as being in a constant state of wonder (Tht. 155d).

Collaboration

The enthusiastic way students referred to collaboration with their peers reinforces previous studies that advocate the beneficial impact of teamwork on learning (Entwistle & Waterston, Reference Entwistle and Waterston1988; Davies, Reference Davies2009). Peer support can be reassuring, while negotiation and the exchange of ideas can facilitate rich learning experiences (Kaye, Reference Kaye, Heap, Thomas, Einon, Mason and MacKay1995; Boud et al., Reference Boud, Cohen and Sampson1999; Boud & Falchikov, Reference Boud and Falchikov2007; Watkins, Reference Watkins2004; Bryan, Reference Bryan, Bryan and Clegg2006). The emphasis laid by some students upon the gradual bonding of team members also supports the view that groups can be more efficient and functional if they are formed early and last for several weeks (Davies, Reference Davies2009). It certainly takes time for a team to become what Gee calls an ‘affinity group’, where members share a sense of common purpose and collegiality (Gee, Reference Gee2007). Rania's comparison of the ad hoc formation of teams to ‘children's play’ raises interesting questions about the importance of at least some kinds of bonding for more serious and focused work. The fact that some students preferred to work individually rather than in pairs for the fourth activity is also notable and might be associated with the need for agency and ownership over one's own learning. Along with the various challenges that collaboration can involve (Davies, Reference Davies2009), this shows that for all its advantages, collaboration is not a panacea. Accordingly, courses should strike a balance and students should also be given the choice to pursue certain tasks on their own.

Motivation

Students’ remarks on the time and effort spent on the tasks and on their feelings of enjoyment imply that they felt intrinsically motivated while working on the activities. This might be associated with the taxonomy of intrinsic motivators for learning identified by Malone and Lepper (Reference Malone, Lepper, Snow and Farr1987), such as challenge (tasks were neither too easy nor too difficult), curiosity (there were novel associations and the activities were revealed one at a time), fantasy (e.g. an imaginary dialogue with a poet) and autonomy (students had a certain level of control over the tasks). In addition, intrinsic motivation was also increased by other factors such as contextualisation (e.g. preparing a presentation for secondary education students (Lepper, Reference Lepper1988)), collaboration and creativity (Barab et al., Reference Barab, Arici and Jackson2005). While intrinsic motivation seems to have persisted throughout the activities, the negative feelings experienced by the majority of students upon hearing about the new method of assessment imply that several students might have not embarked on the activities if these had not been graded (extrinsic motivation). The shift from external to internal motivation shows that the boundary between these two modes of motivation is porous and that extrinsic incentives might prove significant, especially if we want to motivate students to experiment with something novel outside their routinised ways of thinking and acting. As Lepper (Reference Lepper1988) points out, even when one is intrinsically motivated towards an activity, if the activity is challenging and stimulates one's curiosity, its inherent motivational power may be increased. Of particular interest is the example of Rania, who reported that she had felt very stressed at the beginning, but that the emotional satisfaction of completing the second activity had been so great, that she did not even care about her grade. Last but not least, a note should be made on students’ reaction to the prospect of having one of their assignments exhibited at a public event. Even though all students claimed that this had no bearing on how they had engaged with the prescribed task, three students stated that they saw the prospect of the public display of their work as an opportunity to send a message and be heard. Once again, this shows that, depending on how and when it is offered, an extrinsic reinforcer may increase intrinsic motivation. This problematises the view that external motivation, such as rewards, can only lead to superficial engagement (Deci et al., Reference Deci, Koestner and Ryan2001) and might even be detrimental to intrinsic motivation (Hanus & Fox, Reference Hanus and Fox2015).

Engagement and Flow

A theme that came up in all the interviews was the feeling of engagement that students experienced while completing the four activities. This engagement finds eloquent expression in the specific terms in which students couched their experience, but it is also implied in the ways they described particular attitudes and events. For instance, the fact that none of the students mentioned any workload implications is telling. If students had to study for a midterm exam, they would have spent less time studying and the study time would have been concentrated into just a couple days before the exam (Gibbs & Simpson, Reference Gibbs and Simpson2005). The four assignments that students had to complete covered the first eight weeks and required more time overall, an issue also acknowledged by the students themselves, although not in the form of a complaint. This different experience of time might be explained by the fact that the students’ effort was more evenly spread, thus reducing time pressure. The intrinsic motivation that students seem to have experienced while working on the activities might also have been conducive to this, to the degree that motivated students seem to experience a lowered perception of workload (Kyndt et al., Reference Kyndt, Berghmans, Dochy and Bulckens2014). Furthermore, motivation is also a prerequisite for ‘flow’, the feeling that one experiences when one is fully immersed in an engaging activity (Csikszentmihalyi, Reference Csikszentmihalyi1990). In addition to the above, the students’ stance towards workload might also be associated with the fact that the activities did not require the retrieval of factual knowledge or the use of the library for books. This, in relation to the fact that the activities prompted students to make novel associations, seek inspiration from their environment inside and outside the university, and use their smartphones (Morphitou, Reference Morphitou2015) and other social media, which are typically used for leisure, might have made the tasks look less like ‘formal work’.

Technology and Feedback

Student remarks that my interventions in their discussions in Blackboard made them feel secure and in control of their material are supported by research on the benefits of formative feedback during the process of an activity (Hounsell et al., Reference Hounsell, McCune, Hounsell and Litjens2008) and on technology's potential to enhance student engagement with feedback (Hepplestone et al., Reference Hepplestone, Holden, Irwin, Parkin and Thorpe2011). However, although Blackboard creates the opportunity for continuous feedback, it is notable that the great majority of students did not even attempt to start a group discussion there, preferring instead to communicate via other social media, such as Skype and Facebook. The students’ preference, which problematises the unquestioned use of Blackboard as a collaborative educational tool (Maleko et al., Reference Maleko, Nandi, Hamilton, D'Souza, Harland, Pears, Berglund and Thota2013), might be explained by the fact that Blackboard does not support synchronous communication and sharing of knowledge. Rania's comment that her team preferred not to have their discussions monitored because of the informal style of their communication raises other significant questions relevant to the provision of continuous feedback in online environments: how does a facilitator's presence in an online environment affect student interaction? Might the facilitator's presence compromise student playfulness? In what ways does continuous feedback from an authoritative voice in an online environment differ from the continuous feedback received by gamers while playing a game? Another point that needs to be mentioned here concerns the fact that, as well as communicating through social media, all students reported that they had face-to-face meetings with their teams. This detail indicates that the opportunities for synchronous communication offered by new technologies are no substitute for physical presence, at least not in conventional universities. In light of this, before making the use of online environments for collaboration a requirement for students in traditional universities, educators should be able to answer the following crucial question: ‘Why this artefact in this form?’ (Hamilton & Friesen, Reference Hamilton and Friesen2013).

Assessment for Learning vs Assessment of Learning

Students’ identification of midterm and oral exams as the only alternative methods of assessment demonstrates that, in spite of ample research on the benefits of assessment for learning, assessment of learning still prevails. It is also indicative of the lack of diversity in assessment formats and approaches (Race, Reference Race2001) and of the predominantly traditional way in which assessment is carried out in Classics in Greek-speaking universities. The negative way all students referred to midterms (and written examinations in general) reveals their dissatisfaction with and dislike of this method of assessment, while the strategies (e.g. ‘selective neglecting’) they identified as being typically adopted within the current assessment culture have been extensively discussed in assessment literature (Entwistle & Entwistle, Reference Entwistle and Entwistle1992; Tang, Reference Tang and Gibbs1994; Gibbs & Simpson, Reference Gibbs and Simpson2005). The clear-cut distinctions that students drew between midterms and the GIPA also resonate with other research on student perceptions of traditional and innovative assessment (Struyen et al., 2005). Traditional methods of assessment are often perceived as promoting surface approaches to learning and innovative assessment as stimulating deep-level learning (Sambell et al., Reference Sambell, McDowell and Brown1997). Although students’ inexperience with other forms of innovative assessment renders it difficult to determine whether their enthusiasm derived from the novelty or if they actually felt that the game-informed activities had a deeper influence, their responses support previous research on the different learning approaches that students adopt for different assessment tasks (Scouller, Reference Scouller1998). It is also notable that students talked about these activities in a subjective tone, indicative of a more personal and emotional commitment, a condition which, according to Gee (Reference Gee, Ritterfeld, Cody and Vorderer2009) is conducive to deep learning.

Concluding Remarks

The emotions experienced by students while working on the GIPA and the vocabulary by which they articulated their experience confirm the dominant view that, what renders ancient Greek unattractive to many students is not the subject per se, but rather the parochial and outdated way ancient Greek is still taught nowadays. Assessing students in innovative ways that promote a multimodal and alternative approach not only could contribute to learning but could also advance learning as an enjoyable experience. Instead of forcing students to be strategic and play the ‘game’ of assessment, it is crucial that we incite them to be playful with their material and play the ‘game’ of learning. That being said, the initial reaction of the majority of students to the GIPA clearly shows that it does not suffice to simply provide students with ‘ludic spaces’ and ask them to play or be playful. It is imperative that we help them to foster a playful attitude and that we support them emotionally and cognitively to become good ‘players’, in accordance with the Platonic model laid out in Part I. This holds especially true for students who are accustomed to instructional and conservative methods of teaching and assessment and who are, therefore, more apprehensive about innovative assessment and the notion of playfulness.

A final remark and caveat: even though this research project was carefully designed, it still has many limitations. For instance, although I have tried to support my findings with ample references to relevant literature, the use of only one research method (interviews) to collect my data does not allow validation. Moreover, there was no correlation between the students’ remarks and their actual performance or overall achievement on the course, which would have verified that deep learning had occurred. In light of this, further research is recommended, so that we gain a richer insight into the complexities surrounding student engagement with assessment and appreciate the various factors (subjective, situational etc.) that contribute to students’ engagement, motivation and overall enjoyment of the learning process. More research is also needed on the ways in which we can foster playfulness; and also on notions such as surprise and curiosity, which cropped up several times in students’ accounts, but which have not yet been extensively or adequately studied in relation to game-based and game-informed learning and assessment.