The end of January. The Festive Season is well and truly over and students are back in the classroom. There are things to look forward to, of course! The Classical Association is undertaking a Qualifications Review, planning for possible future reforms in Latin, Ancient Greek, Classical Civilisation and Ancient History at GCSE and A level. This is based on the demonstrable mood for change, shown by the responses of teachers in the earlier joint Classical Association/Classics for All Survey of Classics Teaching, a report of which will shortly be published in JCT. The Association will also be putting on its Annual Conference in March in Warwick University – a little earlier than usual due to the Easter holidays. Saturday will be the ‘Teachers’ Day’, with a good number of interesting panels (the other days will be just as good, of course!).

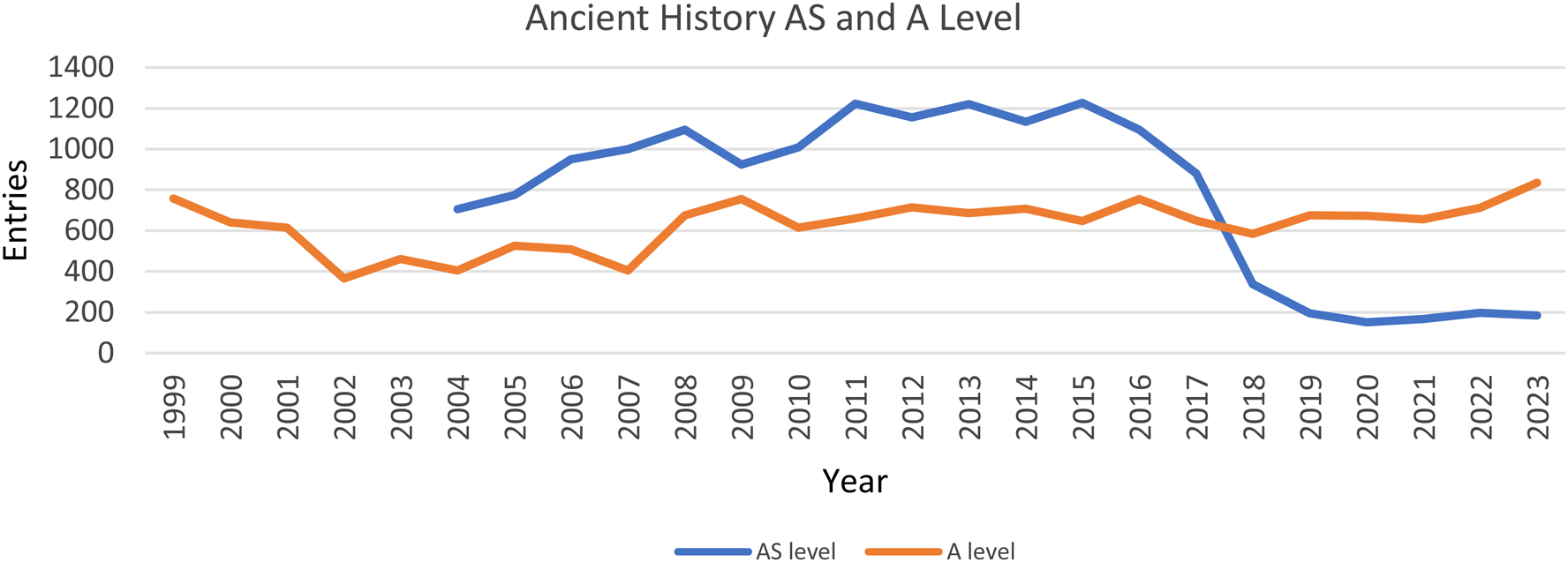

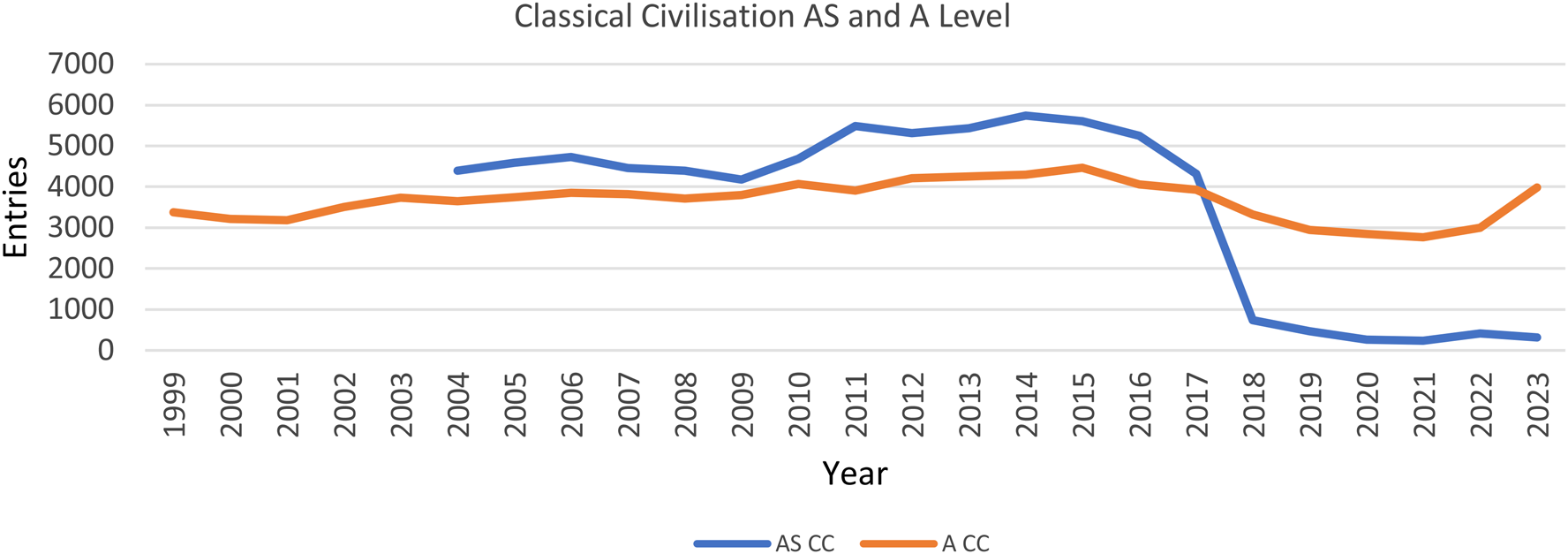

A conference of Ancient History teachers has just been held at Harrow School (30 January 2024), with around 75 attendees. Steven Kennedy, the Head of Classics, was kind enough to invite me to give a brief presentation on the subject of the examination of Ancient History (and Classical Studies more broadly) from an international perspective, based on what John Bulwer and I had found in the research entailed in our forthcoming book Teaching Classics Worldwide. I chose to look at examinations from Australia and New Zealand, which seemed successfully to blend people, places, events and actions, art and literature in ways which would be currently disallowed under present Ofqual rules, but might give thoughts to how the Qualifications Review might be completed and recommendations made. As it is, entries for both Ancient History and Classical Civilisation A Levels were up in 2023 (as Figures 1 and 2 show), which is obviously good news.

Figure 1. A level entries for Ancient History, 1999–2023.

Figure 2. A level entries for Classical Civilisation, 1999–2023.

How, then, to maintain these numbers and, maybe, improve them further? In the not-too-distant past there has been a great deal of concern, rightly, expressed about the subject matter of Classical Studies, focused as it seemed on elites and ignoring the diversity of the ancient world. Various organisations, including the examination boards and text book authors, have since made significant improvements – the Greeks and Romans, Macedonia, Cleopatra, Persia et al. now fall under our remit. But more than ever we need to consider the diversity of those who do the studying. I quoted two teachers who kindly contributed to my research, from Australia and New Zealand – two countries which are especially aware of their duty to all their students. Firstly, John Hayden from New Zealand, discussing the NCEA examinations system:

The external standards in all three tiers focus on core ideas – Ideas and Values, Art and Historical/Socio-Political life. Likewise, the internally assessed standards cover similar ground, but given that these are often attempted in-class, and with a range of source material on-hand, these are the assessments that ākonga [students] are particularly drawn to. The beauty of the NCEA system is that there is scope for kaiko [teacher] and ākonga alike to pursue their proclivities, without making the subject seem rigid and impenetrable – a widely-held misconception, particularly in this part of the world, owing to the subject's perceived ‘elitism’ and erroneous labelling as the domain of the high-brow.

Hayden refers to the NCEA examinations as being 3-tiered. That means that students may take a qualification in each examination at a level which suits their length and depth of study. The other reference to externally and internally-assessed standards points towards to the combination of final, written examinations and continuous coursework-style assessment. It is in the latter that the student (and teacher) may pursue their individual and personal topics and (we might suppose) show their depth of knowledge and understanding with reference to modern scholarship and the reception of the classical world. Secondly, Louella Perrett from Australia wrote:

Intercultural understanding, ethical understanding, twenty-first-century skills are appearing more explicitly in our curriculum, as is the alignment with cross-curriculum priorities. Whilst their integration places greater demands on the teachers, it also offers opportunities for further justification of our subjects. For example, the meaningful and respectful integration of civics and citizenship, diversity and difference, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures can be a persuasive reminder of how studying a classical language can contribute to the formation of young minds and, hopefully, more aware, responsible global citizens. Embracing a broader purpose for the Classics curriculum can go some way towards dispelling the myth of irrelevance.

Perrett describes the essentially humanistic aspect of the teaching of Classics and its importance in a modern, pluralistic society. This has been a common refrain, sometimes lost in the thrust of E. D. Hirsch's ‘knowledge-rich curriculum’ of today. John Sharwood Smith (Reference Sharwood Smith1977) reminded us that students should learn not just about Classics, but also through Classics, a view echoed by Richard Pring (Reference Pring2016) and many others. While most readers of this editorial will know this already, I think we need to make this point again and again, ever more clearly and forcefully, to those whose ideas about the classical world are shaped by poor or dimly-lit or outdated representations of the Classics. But we need more than anecdotes: a place to start would be to identify what those twenty-first-century skills really are. Colin Shelton's (Reference Shelton2023) domain analysis of the work of US college (university) students in upper-division Latin is a first in clearly delineating what skills, practices and understandings these students exhibit in pursuance of their studies. But while his report indicates what students at this high level can do in terms of philology, textual analysis, comprehension and reading, writing and discussing Latin, Shelton has misgivings about making something which only a few undertake at the highest levels the template for all students at lower levels – especially those who do not go on to become university students of Latin:

[I]t would make sense to pursue the more challenging task of thinking about what Latin can do for students beyond getting them ready for upper-division courses they will likely never take (Shelton, Reference Shelton2023, p. 577).

Therefore, rather than taking a one-size-fits-all approach, we might better establish the sorts of skills, practices and understandings we observe, expect and deem worthy of cultivation in all four UK classical subjects at different levels. This may require not a little work, but the results might provide useful information for thinking about what are reasonable expectations for our students, as well as what we can ‘sell’ to parents and the outside world at each stage of schooling. I am sure that we will not hear the last of this.

This volume of the Journal of Classics Teaching presents a wide range of articles and book reviews. There is a small cluster of interrelated articles on teaching classical languages and culture in the primary school – the result of the conference Monsters in the Classroom, which was held online on 22 January 2022 and organised by Evelien Bracke (UGent) and Lidewij van Gils (UvA) and me. Evelien's article is best read first, as both an introduction to the conference papers and about her own work with her Ancient Greek – Young Heroes project in Belgium. This should then be followed by articles by Duchemin et al. (France), Bozia et al. (USA), Di Donato and Taddei (Italy), Van Gils (Netherlands), Manolidou and Goula (Greece) and Hunt (UK). For details of the conference itself, see https://www.oudegriekenjongehelden.ugent.be/conference-report/.

Articles

Peddar, D. Steps towards inclusivity: modifying challenging content, navigating pedagogical materials and initiating student reflection within the Classics classroom

König, A. Teaching Classics as an applied subject.

Díaz-Sánchez, C. and Chapinal-Heras, D. Use of Open Access AI in teaching classical antiquity. A methodological proposal.

Salapata, G., Tracy, J. and Loke. K. Teaching Greek mythology through a scenario-based game.

Forum

Bracke, E. Teaching Latin and ancient Greek in the 21st-century Primary School: Framing local approaches to international challenges.

Duchemin, L., Durand, A. and Franceschetti, B. The Nausicaa experience: Teaching Ancient Greek in French preschools and primary schools.

Bozia, E., Pantazopoulou, A. and Smith, A. J. ‘Translating’ Classics for Generations Z and Alpha.

Di Donato, R. and Taddei, A. “Educare all'Antico”. Teaching Classical Civilisation in Italian primary and lower secondary schools.

van Gils, L. At the gymnasium through your football buddy's aunt. Accessibility of classical education in the Netherlands.

Manolidou, E. and Goula, S. In Greek we trust! Παίζοντες μανθάνομεν.

Hunt, S. Latin and Greek in English Primary Schools – seedlings of a classical education.

Moran, J. As clear as Herculaneum mud: a plea for clarity

Huelin, L. Designing Vocabulous: a Case Study in Classics, EdTech and English Literacy.

News and Reports

Stephenson, D. 43rd JACT Latin Summer School – 2023 Director's Report.

Manolidou, E., Rico, C., Teichmann, J., Coderch, J., Mistretta, M. R. and Hunt, S. Insights on Classics in Praxis at the Delphi Economic Forum.

Book reviews

Bayliss (A). The Spartans: A Very Short Introduction. Jo Lashly.

Brennan (T). The Fasces. A History of Ancient Rome's Most Dangerous Political Symbol. Brian Zawiski.

Daugherty (G). The Reception of Cleopatra in the Age of Mass Media. Lucy Angel.

Downie (R). Memento Mori: A Crime Novel of the Roman Empire. Jodie Reynolds.

Franko (G). Plautus: Mostellaria. Terry Walsh.

Fraser (G). Aristophanes: Peace. Terry Walsh.

Gibson (R). Man of High Empire. Matthew Mordue.

Gray (A). Circus Maximus: Race to the Death. Clare Harvey.

Harper (E). The Wolf Den. Clare Harvey.

Haynes (N). Stone Blind: Medusa's Story. Danny Pucknell.

Jeong (M). A Greek Reader. A Companion to A Primer of Biblical Greek. Cressida Ryan.

Klein (V). Plautus: Menaechmi. Terry Walsh.

Maclaughlin (N). Wake, Siren: Ovid Resung. Emily Rushton.

Marcolongo (A). The Art of Resilience: The Lessons of Aeneas. Brain Zawiski.

Miller (M). The Song of Achilles. Sophia Drake.

Montgomery (A). Walking the Antonine Wall: A Journey from East to West Scotland. Ryan Sellers.

Robinson (L). Telling Tales in Nature. Underworld Tales. Steven Hunt.

Stager (J). Seeing Color in Classical Art. Theory, Practice, and Reception. Timothy Adelani.

Stothard (P). Crassus: The First Tycoon. Jodie Reynolds.

Stuttard (D). Looking at Agamemnon. Danny Pucknell.

Vout (C). Exposed: the Greek and Roman Body. John Godwin.

Waters (M). King of the World: The Life of Cyrus the Great. Barry Knowlton.

Williams (T). Lost Realms: Histories of Britain from the Romans to the Vikings. Timothy Adelani.

Many articles for the Journal of Classics Teaching start up as conference pieces or teach-meet talks or presentations at staff meetings. The Editor always welcomes interesting or novel pieces, as well as articles which simply describe good teaching practice or events or things of interest to other teachers. Readers should feel confident to submit articles in the usual way to the Classical Association.

Submitting an article to JCT

The Journal of Classics Teaching is the leading journal for teachers of Latin, Ancient Greek, Classical Civilisation and Ancient History in the UK. It originated as the voice of the Joint Association of Classical Teachers in 1963 under the title Didaskalos, being renamed Hesperiam over the years, and finally JCT. It has a broadly-based membership including teachers in the primary, secondary and tertiary education sectors. JCT welcomes articles, news and reports about Classics teaching and items of interest to teachers of Classics both from the UK and abroad. If you wish to submit an article, it should be sent to the JCT Editor, c/o the Classical Association.

Articles are welcome on classroom teaching practice or on studies about the teaching and learning of Classics in the UK and abroad should be up to 7,000 words. There should be clear pedagogical or academic content. News and reports of events of general interest to teachers of Classics should be between 1,000 and 2,000 words.

For 50 years JCT and its predecessors were published in hard copy and made available to members of the Joint Association of Classical Teachers. From 2015 JCT has been available freely online, generously supported by the Classical Association.