After the 1855 elimination of a rebel army from Zhili province, the Xianfeng emperor (r. 1851–1861) convoked a ceremony celebrating the “victorious withdrawal of troops” (kaiche dianli 凱撤典禮) in Beijing. The rebels were a branch of the army of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, recently entrenched in Nanjing, occupying the Yangtze Delta region, and threatening the north. Since the autumn of 1853, the Taipings’ northern invasion had encroached upon the capital city and its surrounding “capital region” (jifu 畿輔).Footnote 1 Now, some anticipated and feared that as the war continued in the south, the worthy sacrifices of the north would be eclipsed and go unnoticed. The acting magistrate of Cangzhou 滄州, upon replacing his slain predecessor, pointed out, “Since the rebels cavalcaded into Henan, Shanxi, and the capital region … there were exceedingly few places where Manchu, Han, civil and military officials, gentry, soldiers, and braves fought to kill the rebels as in Cangzhou.” He continued, “Nowhere else was the tragic slaughter as extensive or as stirring.”Footnote 2 The threat to the capital and the suffering felt by its hinterland area had been extensive and deep, and the local response notable.

In the immediate aftermath of the Taiping northern invasion, officials, soldiers, and residents in capital region communities began to rebuild. At the same time, they memorialized this wartime chapter, even as for the rest of the empire, the Taiping War remained unfinished until 1864. To profile the distinctive experiences of the capital region in the early Taiping War, I focus in this article on the walled city and surrounding district of Cangzhou and offer comparison throughout to Beijing and other area jurisdictions.Footnote 3 Cangzhou suffered an especially violent attack in autumn 1853. Afterwards, local men staged executions, collected remains, buried bones, compiled records of the war dead, and wrote reports, petitions, poems, eulogies, and histories. Social reconstruction and local commemoration were connected endeavors. Capital region advocates tapped into the Qing court's post-Opium War prioritization of the North China coast as an area of strategic concern and fortification. They linked bids for funds and resources with Beijing's military needs. At the same time, they justified wartime events and activities—the sacrifices of local martyrs and the returns of wartime fundraising, but also the organization of militias that met no foes or the wholesale slaughter of certain communities—as contributing to the “pacification” of North China. In gazetteers, private histories, and commemorative records, local advocates reframed ambiguous realities to write their localities into a story of northern victory, regardless of what happened in the south.

Notably, whereas this early reconstructive phase took place earlier than the postwar reconstruction (shanhou 善後) of the Yangtze Delta area (where Taiping forces remained entrenched much longer), it remained incomplete when the capital region experienced an additional series of traumas and a subsequent wave of rebuilding.Footnote 4 The second set of tragedies commenced before communities recovered from the population, infrastructure, and economic losses of the Taiping War. In succession, the flooding of the Yellow River as it moved northward, the Anglo-French northern campaign of 1860, the Nian Rebellion and associated rural uprisings, and the North China Famine (1876–1879) all impacted the capital region.Footnote 5 Like the northern sieges of the Taiping War, these events affected capital region districts unevenly. For instance, the Anglo-French campaign resulted in the abrupt depopulation and fortification of Beijing (paralleling the capital's 1853 response), whereas uprisings of Nian rebels and rural bandit groups in the late 1850s struck at the southern hinterland rather than the capital or satellite walled cities of the capital region. Central and southern Zhili were heavily afflicted by the North China Famine, with successive years of drought and death. In the early 1880s, attention to these linked destructive events energized social reconstruction and commemoration, therefore granting renewed attention to Cangzhou's earlier and less recognized wartime plight.

Social, military, and environmental disruptions in the capital region occurred amid a major trend of political realignment that reshuffled and disrupted court power and put regional powerholders in control of swathes of central and north China by the 1880s. Due to its position south of the capital and at the northern end of the Grand Canal, Cangzhou's elite population operated at the juncture of capital-centric and southern-facing networks.Footnote 6 A preface written a few months before the 1853 siege and intended for a revised local gazetteer stated that as part of the “august metropole” (huang ji 皇畿), Cangzhou had been “steeped in [Qing] imperial luster for more than two hundred years.”Footnote 7 At first, Cangzhou residents appealed to the Qing court for funds and honors and solicited attention from scholar-officials residing in the south with historic connections to the capital region. In timely fashion and attuned to capital politics, they advocated local needs, celebrated fallen martyrs, and solicited attention to their districts. To justify their importance and underscore the significance of their losses, Cangzhou and other Zhili communities constantly linked their localities with a symbolic capital region that reinforced Beijing's strategic defense interests. But finding little support from the court, they later moved on to target literati and powerholders in ascendant Tianjin. By the late nineteenth century, practicing strategic localism meant identifying social, political, and economic links with the commercial port city of Tianjin to obtain both state benefits and broader recognition.Footnote 8 In their local advocacy, North China natives helped shift the real and symbolic associations of capital region identity.

The Taiping War Comes North

Beginning in the summer of 1853, a Taiping army made its way north with the objective of eliminating the Qing dynasty from its Chinese capital, Beijing. The fact that Beijing was the ultimate goal is clear from Taiping documents, which describe the urgent need to eliminate the Manchu rulers from this “demon's den” (yao xue 妖穴).Footnote 9 In the Ming and Qing dynasties, the capital city Jingshi 京師, roughly coterminous with present-day Beijing, was located in the [Northern] Metropolitan Region ([Bei] Zhili [北] 直隸).Footnote 10 Zhili (similar to present-day Hebei) was a relatively large and diverse province, in terms of both human geography and (human-influenced) environment. Notable features included the mountainous northwest, the defensive cordon of the Great Wall, the dry wheat and maize-growing areas of the central hinterland, the eastern coast and floodplain, the northern terminus of the Grand Canal and associated waterways, the major commercial and salt-production center of Tianjin, and the imperial metropolis, Beijing.Footnote 11

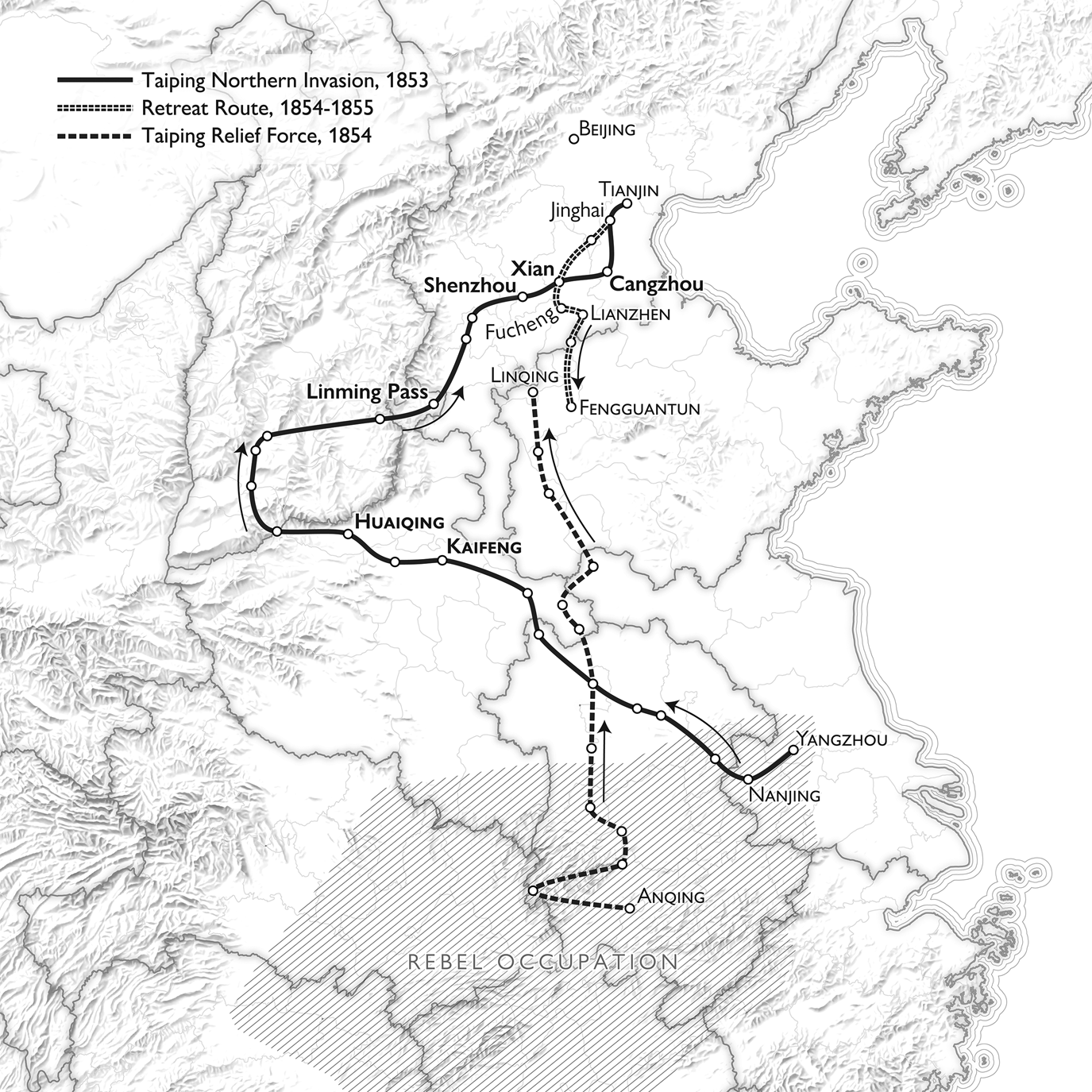

The Taiping northern invasion led by Lin Fengxiang 林鳳祥 and Li Kaifang 李開芳, with its initial expeditionary force of about 30,000 (later swelled by recruits and captives), entered Zhili from the southwest at Linming Pass in the autumn of 1853 (Figure 1).Footnote 12 They were in a strong position, surprising Zhili Governor-General Nergingge (Ch. Naerjinge 訥爾經額) on his return from Huaiqing, where Taiping and Qing forces had been locked in battle for more than two months. With Nergingge's conspicuous failure to stop the rebel army's forward momentum, the Xianfeng emperor leaned on two banner armies, led by Mongol general Senggerinchen (Ch. Senggelinqin 僧格林沁) and Manchu general Shengbao 勝保, as well as speedily organized local militias in Zhili counties and villages. Mongol battalions from the northwest were called up in support. The court ordered the erection of a defensive cordon around Beijing, organized by a new institution led by his uncle, Prince Hui (Hui qinwang 惠親王), the Capital Defense Bureau (Jingcheng xunfang chu 京城巡防處).

Figure 1. The Taiping Northern Invasion, 1853–1855. Map courtesy of Nick Lally, University of Kentucky.

Speaking to the court's strategic vision for the capital region, the Capital Defense Bureau had a broad purview not only in walled Beijing but in its surrounding counties. Their intelligence reports adduce a strategic capital region: a long, narrow band, stretching from Miyun north of Beijing to Chiping in northern Shandong.Footnote 13 The Beijing court and the Bureau followed the idea that controlling the capital region was of essential strategic importance (zhong di 重地). For instance, an edict of early 1853 stressed, “The capital region is an important place. It is especially essential to remain completely under control … henceforth, transients from other provinces, as soon as they cross the border into Zhili, shall, by order of the governor-general to local officials, be taken up and regularly transported back to their native places.”Footnote 14 Here, not only were different terms used to designate Zhili and the “capital region,” but also Xianfeng granted extraordinary powers to local officials to rid the capital of dangerous outsiders. The broader environs of Zhili appeared as a protective cordon for the capital city and the capital region extending to its southern flank.

Given the heavy fortification of the capital, Taiping commanders Lin and Li decided against a direct march towards Beijing. They opted instead to move east across southern Zhili and then north towards Tianjin. A steady stream of spies and informants made their way to Beijing, suggesting that the Qing capital remained a target.Footnote 15 During this journey, the Taiping army plowed through rural counties, acquiring recruits and captives along the way. Period texts record a trail of death, in which more than a dozen county magistrates perished in righteous defense—though several others hid, absconded, or committed suicide.Footnote 16 Besides these officials, most casualties were civilians and local militia members, not soldiers in the banner armies, which generally lagged in pursuit. The rebel army's movement unleashed disorder, as civilians and officials fled, buildings and structures were torn down, and crops were pillaged or destroyed. Local records attest to upticks in “local bandits” (tufei 土匪) in the rebels’ wake, in some cases more destructive than the initial incursion.

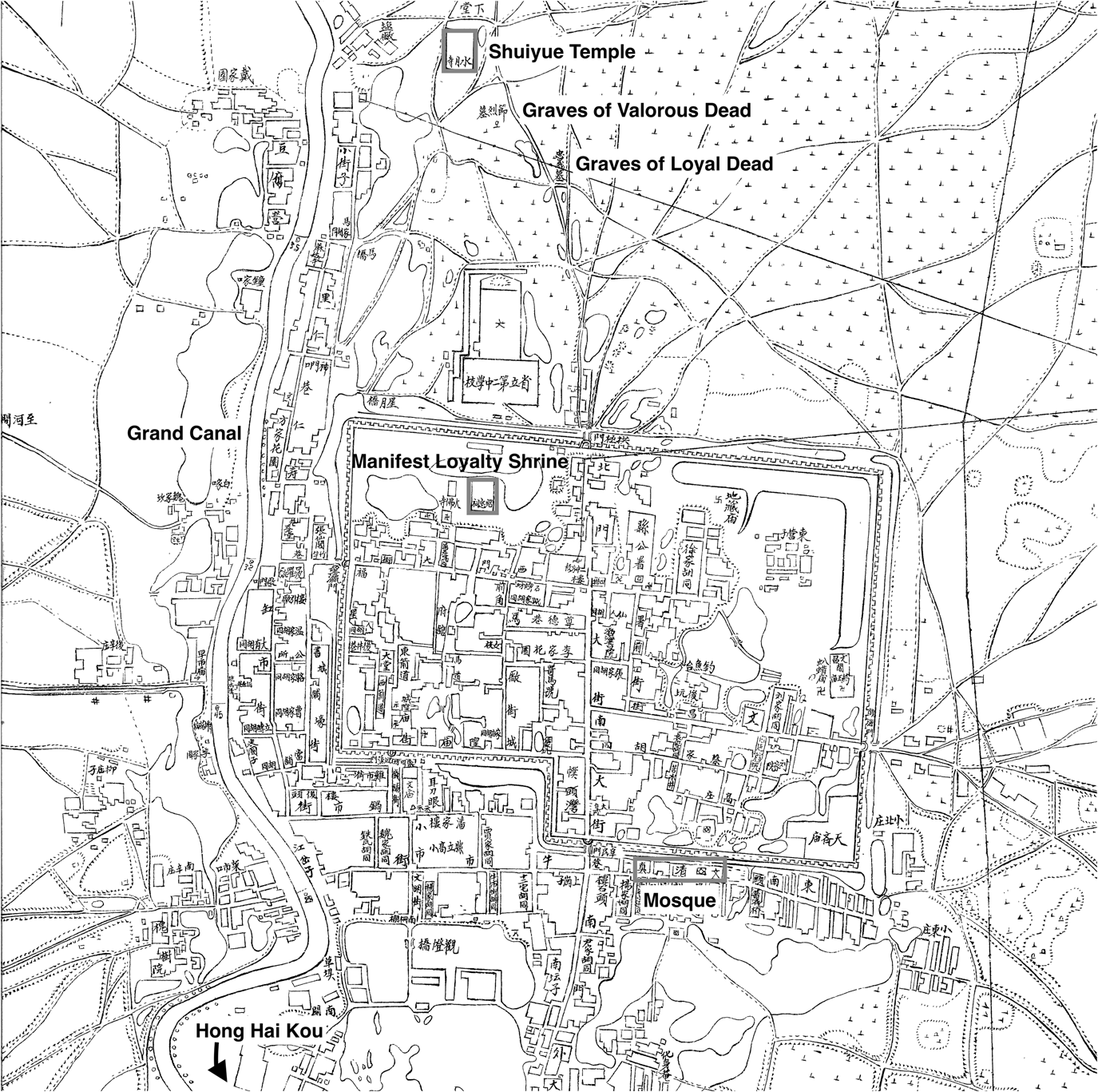

The walled city of Cang, sixty-five miles to the south of Tianjin, was the seat of Cangzhou, an independent department in Tianjin prefecture (Figures 2, 3). Though a rural district, Cangzhou was a notable population center in coastal Zhili. It was a crossroads of land transit from central Shandong to the capital region, and a center of salt production. The walled city sat just to the east of the Grand Canal, and the district stretched to the coast.Footnote 17 Cangzhou was also home to a small White Banner garrison and one of North China's largest Hui Muslim communities.Footnote 18 Here, on October 27, 1853, the invading Taiping faced resistance from what period sources lauded as an especially well-organized militia cooperating with local bannermen and Green Standard Army soldiers.Footnote 19 Heading up the effort were Manchu garrison commander Decheng 德成, local magistrate Shen Ruchao 沈如潮, and expectant official Liu Fengchao 劉鳳巢, a Hui Muslim—neatly representing the main segments of the local community.Footnote 20 Contemporary accounts agree that the local defenders at first mistook the Taiping's vanguard forces for the full army and fought with optimistic vigor, incurring significant losses among the rebels.Footnote 21 When the full contingent arrived, they unleashed a retributive massacre, thoroughly ransacking the city. More than ten thousand denizens perished, about a third of them from the banner garrison.Footnote 22

Figure 2. The Walled City of Cang (From 1743 Cangzhou zhi). The mosque is outside the bottom southeast corner of the walled city. Shuiyue Temple 水月寺, where the remains of the victims of the Taiping siege would be buried, is also marked outside the north wall. The banner garrison and Green Standard soldiers were based outside the northwest wall. The waterway on the left is the Grand Canal. Cangzhou zhi (1743), 1.2b–3a. Digitized by Harvard University Library.

Figure 3. The Walled City of Cang and its Surroundings (From 1933 Cang xian zhi). In the 1933 gazetteer, the Shuiyue temple is marked. Adjacent to it are the “graves of the valorous dead” (jie lie mu 節烈墓) and the “graves of the loyal dead” (zhong yi mu 忠義墓). The small cross marks on the northern, eastern, and southern flanks of the walled city are all graves. The Manifest Loyalty shrine is marked in the northwest corner of the walled city. The map indicates most residential and commercial buildup on the western side of the city, adjacent to the Grand Canal. Cang xian zhi (1933), juan shou, “Cang xian cheng guan tu.”

From Cangzhou, the Taiping forces made their way closer to Tianjin, where they would remain for months. In Jinghai County, just south of Tianjin, Lin Fengxiang and Li Kaifang parted ways. Li moved his remaining forces to the villages of Duliu and Yangliuqing. In this way the Taiping forces, arrayed within three miles of the city, surrounded Tianjin. They were just seventy miles from Beijing. However, they now faced Tianjin's formidable militias, which included thousands of released prisoners and mercenaries together with local merchants. Eventually, the banner armies commanded by Senggerinchen and Shengbao arrived. Now sandwiched by professional and amateur forces, the Taiping commanders decided to hold positions for the winter, feeling themselves to be in a tenable defensive state and hoping for the arrival of a rescue contingent by February. But they were ill prepared for the northern cold. Among northern residents, stories of rebels with frozen toes and limbs circulated widely.Footnote 23

The invasion's denouement happened in slow motion across the southern capital region and the Yellow River plain.Footnote 24 In February 1854, Li and Lin began their retreat, breaking across Qing lines to move south from the Tianjin area into Shandong. Meanwhile, a rescue party originating in Yangzhou and augmented by Qing deserters and other recruits on the way moved north. In late March, the relief army reached as far north as Linqing, before dissipating under pressure from Shengbao's forces. Meanwhile, and for months to come, the remnants of the original army moved only incrementally, entrenched at Fucheng and then encircled by Qing forces at Lianzhen. A smaller group, led by Li Kaifang, burst out towards Gaotang in Shandong, attempting to meet the rescue force. In Lianzhen, Lin Fengxiang's group continued to take casualties, but so did imperial forces. Senggerinchen's troops captured a grievously injured Lin Fengxiang in a mud pit in Lianzhen in early March 1855.Footnote 25 By this time, Shengbao, having failed time and again to secure Li Kaifang—and rumored to have allowed his soldiers to abuse the local populations—was exiled in disgrace.Footnote 26 After replacing him, Senggerinchen pursued Li further south to the village of Fengguantun, sixty miles west of the Shandong capital. The Mongol general ordered the area flooded. Under his command, most of the remaining Taiping troops were killed outright. Eventually, Li and eighty-eight others emerged from hiding to surrender on May 31, 1855.Footnote 27 Senggerinchen and his forces were hailed as heroes.Footnote 28

All told, the incursion by Taiping forces had caused more than two years of havoc in Zhili. This period split into three phases: an anxious preparatory phase in early 1853; an emergency phase between summer 1853 and early spring 1854; and a long denouement until the summer of 1855. Already by mid-1854 it seemed clear that the Taiping forces would not muster enough strength to redirect towards Beijing. Seeing the capital no longer under direct threat, metropolitan officials considered the situation much improved. Somewhat preemptively, Qing officials lauded the “pacification” (suqing 肅清) of the capital province.

Concluding the Unfinished War

Beijing, Cangzhou, and the capital region undertook different sets of commemorative projects to lend symbolic closure to the Taiping War's northern phase. Staging executions, burying bones, building shrines, and drafting commemorative records were widespread practices in the longer postwar period, but few Chinese communities outside of Zhili had begun to practice them in the mid-1850s. Imperial and especially locally directed projects carried out in the capital region in this period foreshadow many more to come in the 1860s and after. In What Remains, Tobie Meyer-Fong addresses shrines, books, and other texts created after the Taiping were routed from central and southern China. Meyer-Fong notes that bids for imperial honors for the “loyal dead” were already widespread and overburdening the bureaucracy in the early 1850s. By the 1860s, in keeping with a broader swing of political power down to the provincial and local level, communities in southern and central China went ahead and built their shrines despite Beijing's delayed approval. The process of burying and recognizing the dead sometimes took many years and elicited questions about how to sort and classify unidentifiable remains.Footnote 29 In Nanjing, Zeng Guofan 曾國藩 adapted a wartime Bureau of Loyalty and Righteousness (Caifang zhongyi ju 采訪忠義局) to build shrines and research eligible nominees for enshrinement. Chuck Wooldridge notes that the commemoration of Nanjing locals lagged behind the enshrinement of Hunan Army personnel, contingent on the return of elites to the city.Footnote 30

In the capital region, the triumphal narrative of pacification that emerged from early 1854 onward was oriented around Beijing. But rebel forces remained entrenched in southern Zhili for another year, though they no longer threatened the capital. Most civilian casualties were incurred in southern and southeastern Zhili, and most of the men executed in Beijing for rebel conspiracy were Zhili natives who had joined the Taipings either voluntarily or as captives.Footnote 31 The rebels’ transit across the province had destroyed infrastructure and crops and unleashed an upsurge of banditry and brigandage. What's more, court support for recognition of war dead and reconstruction of destroyed property lagged. In the end, the Taiping pursuit of the capital city had inflicted most of its pain on the surrounding region, where local people often contended with the rebel incursion and its aftermath without the support of the massive armies the court had mustered for the capital's defense. Whereas court and metropolitan voices hastened to celebrate the vanquishing of the rebel invaders, locals warned that nearby sacrifices had been ignored.

Surveying Destruction in Cangzhou

In the late autumn of 1853, Cangzhou residents and officials began to survey the damage and the dead. Their work was locally directed, as Beijing remained in the throes of panic and defensive measures against the Taiping forces, now situated closer to Tianjin. As wartime capital and erstwhile target of the rebel campaign, Beijing experienced significant disruption even though the capital city did not see fighting.Footnote 32 Meanwhile, in Cangzhou, district magistrate Shen Ruchao, garrison commander Decheng, and many other local officials had died in the fighting. Chen Zhongxiang 陳鍾祥 (b. 1810), dispatched as acting magistrate, did not arrive for a month afterward.Footnote 33 Once on the ground, he solicited a report on the siege from three remaining officials, including the only surviving officer of the local banner garrison. He also obtained assistance from Dong Youyun 董友筠 (jinshi 1814), a distinguished and locally influential retired official.

According to Magistrate Chen's report, social conditions in the walled city and surrounding area were disrupted. Attempting to count the enemy dead, Chen found more than five hundred severed ears, representing a much larger total number of Taiping casualties. He then surveyed the city and found government offices, courier stops, the jail, and several thousand residences levelled to the ground, and the city wall in considerable disrepair. Besides this, the fighting had consumed temples, armories, and other local infrastructure. Much of the local population, especially merchants, had run off. The local banner garrison was nearly empty. Bandits took advantage, plundering empty residences and attacking travelers on the roadways. The ethnically mixed remaining population was not getting on well. Chen blamed the spate of thievery and brigandage on the “fierce” Muslim residents. He closed the report by noting that rumors of further violence remained rampant because the Taipings were now entrenched fifty or so miles to the north of the walled city of Cang. The rumors made the local population jittery and impeded a return to normalcy.Footnote 34

Chen immediately took action, “inspecting and administering disaster conditions, collecting and burying left-out bones, arresting and prosecuting local bandits, calling back the dispersed populace, and putting the empty city to right (wuzuo kongcheng 兀坐空城).”Footnote 35 He planned to call back merchants and other city residents to resume their trades. Addressing local Muslims, the acting magistrate stated that he would offer an amnesty program for confessed thieves, mediated by community elders, for one month. After that, he would proceed with executions on the spot (jiudi zhengfa 就地正法). Beyond the walled city, Chen planned to expand mutual surveillance (baojia 保甲) and militia training projects to better organize the jurisdiction's 572 villages and make them both defensible and tranquil once more.

True to his word, Chen Zhongxiang aggressively “upheld the law” (chifa 持法) during his remaining time in Cangzhou.Footnote 36 Most famously, he staged multiple public executions of bandits and troublemakers. Zhili Governor-General Guiliang 桂良 cited Chen's prosecutions as examples of effective local action against bandits who abetted the Taipings, alongside counterparts in nearby Hejian, Yanshan, and Dacheng counties.Footnote 37 Not all were happy with these methods. Cangzhou resident Dong Qingbiao 董清標, known for his restoration of the Confucian temple and militia leadership, intervened more than once to save the lives of the “suspicious individuals” (xingji keyi zhi ren 形跡可疑之人) that the zealous magistrate sentenced to immediate death.Footnote 38 In Beijing, a swath of metropolitan officials urged moderation in the treatment of people pushed to brigandage by poverty and warfare. They suggested that soup kitchens and other relief efforts might keep the immiserated from joining up with bandits or even the rebels.Footnote 39

Local community members initiated projects to offer closure to the war's chapter in Cangzhou. The members of the Righteous Bureau for the Burial of Bones (掩骨義局 Yan gu yi ju) included Liu Jinyong, Ma Longjia, Dong Rulin, Yu Defu, Dai Zuolin, Ma Meisheng, and Liu Fengwu.Footnote 40 These “good men” (shan shi 善士), including the brother of slain militia commander Liu Fengchao, belonged to prominent local families, including Hui Muslims. They paid strict attention to separating the bones of male and female corpses and were said to work tirelessly amid the rain and snow. They buried the bones in the marshlands east of the Shuiyue Temple. In time, an honorary stele denoted that the remains of 2,864 individuals had been interred, with male and female burial grounds separated by more than 4,000 feet (1,814 gong 弓).Footnote 41

Examples of compassionate assistance catalogued in local gazetteers suggest a successful, community-driven reconstruction process, combined with a diligent, if rigorous, official patron in magistrate Chen. These projects took place both in the walled city and in surrounding villages. Dou Shaokui 竇紹奎, for instance, distributed grain to those who fled. The next year, tax payments came due with urgency owing to Beijing's need to supply military stipends. Dou organized a group of merchants to cover a 4,000-tael tax bill.Footnote 42 Han bannerman Wang Yutang 王玉堂 declared that he had had enough with the brigandage that ensued after the siege and organized men from more than seventy nearby villages into a militia. On the one-year anniversary of the siege, the villages rewarded him with a doorway inscription. Magistrate Chen concurred that he hadn't had to worry about the western side of the district due to Wang's vigilance.Footnote 43 Teng Longtian 滕龍田 heard about a group of students who were stranded after fleeing a bandit attack on their way back from the prefectural exam and rescued them by boat.Footnote 44 Despite the acting magistrate's warnings of persistent local disorder in late 1853, the community would seem to have persevered in united fashion.

Public Executions to “Comfort Loyal Souls”

In Beijing, in the first half of 1855, the Xianfeng court announced a shift away from defensive entrenchment and towards themes of celebratory reconstruction. Early in the year, Lin Fengxiang was seized from a pitiful cave at Lianzhen, a village on the southern outskirts of Cangzhou. The emperor immediately bestowed honors upon Senggerinchen and his troops and declared the capital region “pacified.”Footnote 45 Over the next few months, the court ordered the decommissioning of troops, institutions, and special measures oriented around capital defense, all upon the rationale that the defensive emergency was now over. In surrounding areas, defense bureaus and militias were also dismantled.Footnote 46 By summer, upon the rout of a reduced rebel force at Fengguantun and the live capture of Li Kaifang, the Xianfeng emperor issued edicts that defined the capital region as “pacified” in more formal terms. He further ordered the bestowal of honors upon meritorious troops, officials, staff, and civilians.Footnote 47 These celebratory announcements were circulated in capital gazettes to officials throughout the empire—at least where communication routes to the capital remained intact.Footnote 48

Public attention in Beijing hinged on the punishment of key rebel leaders associated with the northern invasion, the investiture of honors for Senggerinchen and his subordinate commanders, and the dismantling of emergency measures for security and surveillance. In the early summer of 1855, Li Kaifang and several henchmen were delivered to Beijing.Footnote 49 Like other Taiping adherents arrested during the invasion period, the men were publicly executed with their heads hoisted for display. A clerk for the Capital Defense Bureau wrote that the city walls were covered with red victory banners, and the people's cheers “filled the streets.”Footnote 50 The emperor ceremoniously presented Senggerinchen and Prince Hui with swords and honorary titles.Footnote 51 The court then closed the Capital Defense Bureau and returned its staff to their normal roles. It allowed for the relaxation of nightly patrols and city gate surveillance enacted since the initial alert had gone out. As Daniel Knorr has pointed out, precarious finances pushed both provincial and court authorities to shutter militias and other defense initiatives as soon as urgent threats seemed to pass.Footnote 52

At Senggerinchen's impetus, Cangzhou had its own version of these executions thrust upon it. From those apprehended at Lianzhen together with Lin Fengxiang, Senggerinchen selected thirty-four high-ranking members of the Taiping organization (e.g. men who held “false titles” 僞職) and sent them in custody to Cang for public execution. The Mongol prince planned to send additional fugitives to other afflicted communities. In describing these actions to the throne, Senggerinchen suggested that the ceremonial execution of these rebels would “comfort loyal souls” (wei zhong hun 慰忠魂).Footnote 53 With magistrate Chen Zhongxiang overseeing the proceedings, the execution took place at mid-morning four days later at Hong Hai Kou (紅孩口), a clearing adjacent to the Grand Canal south of the walled city where locals had first faced off against the Taipings.Footnote 54

The Xianfeng court therefore heralded the end of the Taiping War in North China in the first months of 1855 by marking sites and figureheads of martial pride. It singled out high-profile Taiping rebels for public retributive justice. In so doing, it drew upon earlier battlefield and capital-centered executions of what Daniel McMahon has called “apex rebels.” Most notably, in 1828, the Daoguang emperor had ordered the live capture and transportation to Beijing of Jahangir Khoja, leader of a major rebellion in and around Kashgar. Jahangir's execution had amounted to a public display, receiving notice in court paintings, private writings, and Western newspapers.Footnote 55 Suburban communities like Cangzhou, however, did not independently follow the court's example in enshrining military valor or performing rituals of retribution. Cangzhou locals were ambivalent about the public executions and focused on mournful commemoration rather than celebration.

Creating Cangzhou's Record of Martyrdom

Even before the court's celebratory dictates, capital region residents had begun to consecrate fallen locals and define a narrative for the recent massacre. In Cangzhou, a large, diverse, and shifting group collaborated over years in the composition of the Record of Martyrs at Cangzhou City (Cang cheng xunnan lu 滄城殉難錄).Footnote 56 The Record project began with Dong Youyun, the retired official who had initially helped magistrate Chen Zhongxiang to assess conditions. Shortly thereafter, Dong retreated to a distant village, where, in addition to his ongoing project of revising the local gazetteer, he wrote “A Brief Record of the Loss of the Walled City of Cangzhou” (Cangzhou shicheng jilüe 滄州失城紀略) and organized a petition to erect shrines for two deceased heroes: Shen Ruchao, the fallen magistrate, and Decheng, the slain banner garrison commander.Footnote 57 Like many retired officials, Dong had been tasked with organizing militias in his hometown, so he was well acquainted with the details of the slaughter. The petition projected that the names of slain residents, both bannermen and civilians would be recorded in the city's yet-to-be constructed Manifest Loyalty Shrine (Zhaozhong ci 昭忠祠). It was sent to the provincial level, whereupon it was validated by Governor-General Guiliang.Footnote 58

After Dong Youyun's death in 1855, a small group of native sons took up his literary projects. Initially, when Dong died, Ye Guishou 葉圭綬 and Wang Guojun 王國筠focused on completing the county gazetteer. The two young scholars, also first cousins, filled their additions with descriptions of rubbings from bronze and stone.Footnote 59 When Ye presented the incomplete work to erstwhile magistrate Chen Zhongxiang for review and asked for a preface, the official scoffed. The gazetteer contained little notice of recent events, nor the people's sacrifices!Footnote 60 Upon his suggestion, Ye and Wang joined up with Yu Guangbao 于光褒, recently active in collecting biographies of the fallen.Footnote 61 Leaving the county gazetteer aside, the trio began work on what which would become a four-volume tome combining narratives of the city's valorous resistance to the rebel siege, official documents testifying to the events and commemoration efforts, lists and biographical details of the thousands who died, and poems reflecting on the tragedy.Footnote 62 Dong Youyun's short history of the tragedy was a centerpiece of the project.

Though initiated by a few elite Chinese men, the Record of Martyrs compilation project enlisted a large and ethnically mixed authorship and editorial staff. It corroborated the district's claim to enormous loss by documenting the deaths of thousands of residents. High-ranking Manchu and Mongol members of the local White Banner garrison were prominent sponsors. At the “executive producer” level were “supervisors” Fuhai 福海 and Fengšengge (Ch. Fengsheng'e 豐陞額), both high-ranking bannermen from the garrison, and the preface writers, magistrates Chen Zhongxiang and Lianjun 聯儁. An array of bannermen, expectant officials, degree holders, and students interviewed survivors about the dead and compiled the volumes.Footnote 63 Eighteen Cangzhou residents composed poems for the volume, including banner officials Guimao 桂楙 and Selüchongge 色捋沖額.

Though many of the sections of the text were written in the immediate aftermath of the disaster, the first version of the Record of Martyrs was completed in December 1862, nearly a decade after the siege of 1853.Footnote 64 A second, updated edition was published in 1881 under the same title upon the occasion of the construction of a Manifest Loyalty Shrine at Cangzhou.

Defining Loss in the Cangzhou Community

Cangzhou authors emphasized the distinctive collaboration of bannermen, Chinese, and Muslims—all locals—in defending against the Taiping siege. Throughout the Record of Martyrs, compilers invoked both implicit and explicit hierarchies to organize names, descriptions, and commemorations of those who had died in this heterogenous community. Tables 1 and 2 reflect the ordering of the dead in the Record of Martyrs. At the most general level, the compilers sorted bannermen before Chinese. The banner volume was organized according to status within the banner organization. Supplementary notes clarified that Manchu personnel were listed before Mongols, and Solid White Banner personnel came before Bordered White. Women came after men and followed the same hierarchy of banner ranks, with female dependents grouped with wives and male dependents usually grouped with men. The volume for Chinese residents had different and fewer categories. Here, trained militia brigades were placed before ordinary residents, natives of other places, or even local gentry. About one hundred outsiders perished in the onslaught, most of them residents of neighboring jurisdictions, but also four convicts relocated to Cangzhou via internal transport.

Table 1. The Dead in the Record of Martyrs, vol. 2, “Banners.”

Table 2. The Dead in the Record of Martyrs, vol. 3, “Han People.”

One category of identification obscured in the rolls of the Cangzhou dead were Chinese Muslims. This omission is at odds with the descriptions of the dead written immediately after the siege by Chen Zhongxiang, who specified that he had performed interviews among Manchus, Han, and Hui. Liu Fengchao, the Muslim militia commander recognized as a key figure in the city's defense in other sources, is listed first in his category of militia brigade commanders, but without mention of his Muslim background. Liu suffered a gruesome death: after leading a militia campaign against the rebels, he retreated home to prepare to fight again. Suddenly, a group of rebels burst into his home. Seeing his militia training manual, they were enraged and tied him to a pillar, stabbing his eyes, cutting off his arms, and then dismembering the man who “would not shut his mouth” as he kept berating them to the death.Footnote 65

When interviewers were able to obtain descriptions of valorous death, like that of Liu Fengchao, they placed these individuals first. The Record's “Principles of Inclusion” specifies this move as improving “ease of reading, not to say one was better than the other.”Footnote 66 But value judgments were employed. The category headings explicitly designate “martyred” (zhenwang 陣亡) dead before less valorized forms of death. Martyrdom was subordinated to status. Gentry men who died less-valorous deaths were placed before ordinary residents: military degree-holder Jia Yongguan, who drowned himself and his son, appeared before the commoner Liu Guochun, who wielded a bamboo staff to meet the rebels in battle.Footnote 67 Recurrent sub-headings grouped and sub-totaled forms of death: for instance, “six of this category died of suicide,” or “one hundred and twenty-eight of this category died by throwing themselves in wells.” Some of the descriptions of less-valorized deaths quietly admit to the ambiguous mixture of loyalties and priorities in this early wartime siege: “Yang Zhenbiao allowed the rebels to enter government offices, but did not give them food or join them—was killed,” “Zhang Huzhong met his end while repairing the city wall,” “Ma Qiu and Xu Fuyou were captured by the rebels and taken north but refused to follow—were killed.” Several were killed seeking their mothers.Footnote 68

Strategic Localism in Poetic Representations

The biographies and records of the local dead became source material for the final section of the Record of Martyrs, devoted to ritual, poetic, and prose writings. In total, it contains eighty-one contributions, by both locals and non-residents. Most of the texts were written in the initial compilation period between 1853 and 1862. A second set of poems may have been collected around 1880, when Cangzhou finally received an imperial order supporting its desire to erect a shrine to honor the worthy dead. At this time, it was decided to print a new edition of the Record of Martyrs with a new colophon.Footnote 69 Proceeding in a rough chronological order of composition, the ordering of information within this volume followed the same social hierarchy as the catalogue. Thus, the poems began by treating the city's tragedy in general terms. They then moved on to individual subjects, with the deaths of Shen Ruchao and Decheng, the designated heroes of the saga. Next came soldiers, militia commanders, militiamen, commoners, and finally women and other female dependents. More than the other volumes, however, the poems highlighted female suffering and resistance, particularly that of banner women, who died in large numbers (as seen in Table 1).

The meticulous ordering of materials in the fourth volume indicates compilers’ work to make poetic contributions match the desired hierarchical representation of the community. Paging through the volume, certain anecdotes recur: a thousand women, gathered on the Cang city wall, hurling tiles and stones at the rebels; the night that fallen blood on the battlefield shone like fire and then vanished; and others, often with descriptions neatly matching those found in the earlier records of the dead. As in the battle narratives and death records, the poetic section of Record of Martyrs also distinctly elevated the Manchu dead. A ritual text contributed by Yu Guangbao eulogized the war dead by flipping the dead Manchu and Mongol bannermen into the role of the Song dynasty army fighting off the Jin (now the Taiping), and casting Manchu bannermen Decheng as Chinese military hero Yue Fei.Footnote 70

Sections of the Record were circulated for reactions and contributions. Yu Guangbao, the poetic energy behind the project, composed eleven entries, including the lengthy forty-eight-stanza “Song for Virtuous Ladies” (Lie nü yin 烈女吟), and many of the solicited poems responded to this work. Most of the contributors were based in Tianjin and surrounding counties of the capital region, but there were also natives of Shandong, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang. At least fourteen female poets were included.Footnote 71 The women's geographic distribution resembled those of male contributors, with one local, four Tianjin natives, one from Shandong, one from Zhili, and the remainder originating from Jiangnan, although most now resided in the north. No contributors were based in Beijing. The compilers’ ability to solicit original poems at a distance from in these decades of war is notable, given disruptions of infrastructure and communications.Footnote 72

In the circulation of the draft and the solicitation of new poems, we can see the social connections and networks of the compilers and their desired connections for their community. Of the trio, both Yu Guangbao and Wang Guojun were prolific anthologists. So too were a few of their contributors, including Xu Gaonian 徐嵩年 of Rugao (Nantong) and Gao Jiheng 高繼珩 of Baodi. Some were pen-pals of Yu Guangbao, including Mei Baolu 梅寶璐 and Yang Guangyi 楊光儀, both based in Tianjin.Footnote 73 Others, southern natives who had served as county magistrates in Shandong in the late 1840s, were likely contacts of the third compiler Ye Guishou's brother Ye Guishu 葉圭書—a career official in central Shandong in the 1840s and 1850s and a prolific poet and anthologist himself.Footnote 74

The many poetic contributions vary in quality and in depth of emotion, based on authors’ proximity to the events in Cangzhou—or to other wartime traumas. Some of the poems by outsiders have a flat quality, because they were based only on second-hand reports and locals’ poems, rather than on first-hand experience or interest. Liu Youming 劉有銘, a well-known metropolitan official who had advocated for more recognition of the war dead in his native Tianjin, wrote eight short poems. His prefatory remarks admitted that his knowledge about the siege had been obtained solely from the circulated text, and so he had to guess at some names and details.Footnote 75 Chen Yunlian 陳蘊蓮, a female poet and Jiangyin native, must have felt deeper connection to the district's trials, as she had lived as a refugee for a decade in the 1840s, and wrote extensively about death and loss in her family due to war and invasion.Footnote 76

Cangzhou's bids for recognition moved slowly through the imperial bureaucracy. In late 1853, the Board of Rites acknowledged Shen Ruchao and Decheng as martyrs but declined to include them in the capital's Manifest Loyalty Shrine.Footnote 77 The reports of a massive death toll in Cangzhou met with doubt and scrutiny from the court. Was there any fraudulent recording of deaths? The skeptical court required repeated inquiries on the numbers of dead both in Cangzhou and nearby Shenzhou, but state-led inquiries were prioritized over those already taking place in local communities. Although locals had moved quickly to collect records of the dead, these records were not solicited by the court until years later. In early 1864, Wang Guojun, now an expectant official, brought a copy of the Record of Martyrs to the Censorate (Duchayuan) in Beijing, and it was thereafter presented to the Grand Council for review.Footnote 78 Another long wait elapsed until the construction of the Cangzhou Manifest Loyalty Shrine in 1881.Footnote 79 No shrines devoted to local heroes Shen Ruchao and Decheng were ever built.

Strategic Localism in the Capital Region

The men of Cangzhou were not the only capital region residents who commemorated the Taiping War. Locals in nearby Yanshan county 鹽山縣 also recorded their losses.Footnote 80 In addition to a succession of lists of names submitted for inclusion in shrines (qing jing ce 請旌冊) curated by Shuntian prefecture, similar records were collected in Tianjin, Jinghai and Qing counties. Besides these, at least ten Zhili jurisdictions undertook gazetteer projects between 1854 and 1860.Footnote 81 Area residents also authored histories of the war's events and treatises on local defense efforts. Projects composed for the attention of the court—whether literary enterprises or records of military expenditures—showcased the ways that the locality had played its proper role as part of the strategic “capital region” defending Beijing. Authors worked to promote narratives that tied the jurisdiction to the dynasty above circulating tales and private histories that suggested more complexity.

The invasion's impact on counties south of Beijing was indisputable, but local authors needed to reckon with events that could be interpreted as failures to contribute to the dynasty's success in repulsing the invasion. For this reason, local records finessed wartime histories, even minimizing losses for the sake of preserving reputations. Though the Taipings spent months in Jinghai, the county gazetteer compiled in 1873 barely mentioned the encampment. Small wonder, as magistrate Jiang Anlan 江安瀾 had “felt not up to the task and entered the water, drowning there.”Footnote 82 In Xian county 獻縣, Li Changqi 李昌祺, appointed as magistrate in 1855, compiled interviews of residents describing the rebel siege. He catalogued them and attached a preface. Li understood the delicacies of recording and judging recent events and actions: he would not include details of living degree-holders, as “the verdict on them is not yet set.” Other living men required attention: “Ordinary men and the poor, are on the other hand recorded, since they have no power of their own, and we fear that as time goes by, they will be lost. So too will chaste women and widows be recorded.”Footnote 83 Xian county was another place where the wartime magistrate had fled rather than fight, though local degree-holder Ni Yunpeng 倪雲鶴 had acquitted himself nobly by fighting to the death. When his corpse was recovered, strands of rebel hair were found under his fingernails.Footnote 84

Even in Cangzhou, there were gaps in the claim that locals had uniformly supported dynastic success. One still-circulating narrative gives an alternative account of the Cangzhou siege in which residents of outlying villages joined with the rebel force instead of trying to arrest its progress. On the day the Taiping representatives were executed, it is said, the people refused to leave their homes.Footnote 85 In neighboring Shenzhou 深州, magistrate Chen Xijing 陳希敬 had famously sat at his desk and resolutely admonished the arriving rebels until his cruel death. But it was then revealed that some sectarian “bad monks” previously driven out by Chen had joined up with the rebels, and Chen's assassin was not a rebel, but one of those retributive monks.Footnote 86 Both of these stories complicate the appearance of noble standoffs between clearly delineated loyal subjects and rebels. Not surprisingly, neither story appears in the postwar commemorations that local elites sent up to Beijing and circulated to their social networks.

Other narratives, rumors, and letters concerning the war's northern events written in the 1850s foregrounded uncertainty and ambivalence rather than martial valor (Beijing's preferred theme) or tragic sacrifice (the motif of local memorialists). The narrative descriptions included Chen Zhongxiang's Short Biographies of Various Nobles Perished in the Capital Region in 1853, Yao Xianzhi's Brief Account of the Ravages of the Guangdong Rebels from South to North, and Brief Account of the Pacification of Bandits in the Capital Region, written by an erstwhile resident of Nangong 南宮, in southern Zhili. The anonymous author of Brief Account of the Pacification of Bandits in the Capital Region, for instance, speedily recounted the northern incursions and combat in each location. In his telling, some magistrates martyred themselves, some were slaughtered, some ran away, some were responsible for the loss of the city, and some met unknown fates.Footnote 87 Reports on the events, written in prose and poetry, also traveled as letters and in the hands of fleeing refugees. As Susan Mann reconstructs, poet Wang Caipin 王采蘋 wrote of her aunt, who fled Beijing in 1853, “rumors of war press you on your homeward journey.”Footnote 88

Given the uneven imperatives of strategic localism, wartime events appear differently in wartime history, administrative report, and subsequent local history. The author of Brief Account of the Pacification of Bandits in the Capital Region recorded that magistrate Chen Denghan 陳登漢 of Ren County 任縣 was injured more than ten times but did not succumb to his wounds. However, he then abandoned his post and absconded with the local jailor.Footnote 89 Observing from Cangzhou, Chen Zhongxiang offered a more nuanced accounting:

When the acting Ren County magistrate Chen Denghan heard of the rebels’ arrival, he pledged to stay to the death, and was pierced by rebel knives in thirteen places. It seemed he would die at his post. However, the next day he was rescued by helpful locals and revived, many months later recovering his health. Later, he was nonetheless named responsible for the loss of his post, and eventually he died on the road—alas! There are definitely those who are lucky in death and those who are unlucky. So, Chen could be said to be unlucky that he did not die. Even though he pledged and had the will to stay to the death, yet he did not perish!Footnote 90

As a district official whose reputation and career depended on his ability to both remain alive and stay at his post, Zhongxiang felt he understood Denghan's dilemma. The Ren County gazetteer compiled years later only mentions that magistrate Chen suffered injury, and then describes the destruction of the county seat, vaguely alluding to the possibility that serving officials had fled.Footnote 91

No court-sponsored histories of the Taiping northern invasion were produced until the Imperially Commissioned Campaign History of the Suppression of the Southern Rebels (Qinding jiaoping yuefei fanglüe) was published in 1873. Therefore, in the intervening period, localist records and disparate private histories circulated in the absence of an orthodox record. In representing wartime events, capital region jurisdictions adopted distinct tactics to define their activities as lending to the strategic defense of the capital and contributing to dynastic success in the north. Given the timing of its completion, it is not surprising that the official campaign history downplayed northern events in its selection of documents and events to supply a standard narrative for the entire war, contributing to the elision of the war's impact on the capital region, as predicted by Cangzhou magistrate Chen Zhongxiang two decades earlier.Footnote 92

Cangzhou and the Capital Region in the Late Nineteenth Century

Whereas the 1855 routing of the Taiping armies from the capital province had signaled a victory for the dynasty, North China experienced a catastrophic series of human and environmental crises over the next quarter-century.Footnote 93 In Cangzhou, the combination of periodic rural unrest, raids of bandits and salt smugglers, and inattention from higher levels of government combined to prevent substantial rebuilding in the first decade after the Taiping siege. Though its numbers were quickly restored, Cangzhou's garrison was only resupplied with guns in 1857.Footnote 94 The local economy had collapsed during the siege and incumbent disorder, with broad social repercussions. For instance, the local fire-fighting association went into arrears when the local bank (Fushun dang 阜順當) holding their assets collapsed and its proprietors fled. They were drawn into litigation, and matters were not resolved for years.Footnote 95 Around 1858, a visiting official recorded his shock and surprise that conditions remained so poor in Cangzhou given that years had elapsed, and the region was “pacified.” He noted the continued presence of unburied bones and blamed the Taiping army's scurrilous practice of placing captives in the advance position as cannon fodder. Locals had not known how to treat these captive remains.Footnote 96

Infrastructure remained in shambles for even longer, as new threats and challenges emerged. The city walls, damaged in the attack, were not repaired until the late 1860s. Some government offices were not rebuilt until well into the Guangxu era, with the district magistrate working out of a rented residence for nearly thirty years.Footnote 97 Whereas Cangzhou lay far north of the Yellow River's deadly flooding, it did experience repeated incidences of drought, earthquake, epidemic disease, and famine. In these desperate periods, “roving bandits” (liu zei 流賊) and salt smugglers roamed. In 1868, more than 70,000 men affiliated with the Nian Rebellion briefly invaded Cangzhou, though the district faced relatively few losses. The suffering was felt more keenly in 1876 and 1877, when ten months of drought were followed by the North China Famine. In Cangzhou, as in other areas, the starving and dead lay in the streets, and “weeping was heard at all hours.” A new magistrate's office, Manifest Loyalty Shrine, and even a telegraph office for Cangzhou came in a sudden spate in 1880 and 1881 after many years of paralysis.Footnote 98 By the late 1880s, Cangzhou's location was described in dour terms: “In this land on the Bohai Sea, the earth is saline, the people are poor. After the combined disaster famine, it is marginally improving.”Footnote 99

The Capital Region and the Rise of Tianjin

The late Qing revival of attention to capital region identity and memory was associated with the resurgence of political power in North China, the economic rise of Tianjin as an international port city, and the intensification of ties between prosperous Tianjin and its impoverished rural hinterland. The demise of the Grand Canal system in the mid-nineteenth century, the inland ravages of the Taiping War, and the city's designation as a treaty port in 1860 elevated the city's commercial and political stature. It also grew substantially in population, including its foreign population of merchants, consuls, and missionaries. In 1870, friction between the local urban population and Catholic missionaries culminated in the murder of sixteen French nuns. This ignominious event was a major turning point in both Qing foreign relations and in the city's history. War hero Li Hongzhang 李鴻章 (1823–1901), trusted by foreign diplomats, was appointed Governor-General of Zhili and spent most of his long tenure supervising conditions from Tianjin. During this time, Tianjin was designated the epicenter of imperial relief efforts for the devastating North China Famine, which afflicted a sizeable population—including the residents of adjacent Cangzhou.Footnote 100

Key powerholders saw enhancing the cultural pedigree of the “capital region” as complementing the economic and political rise of Tianjin. They encouraged writing local gazetteers, collecting poems by northerners, and building shrines to commemorate worthies of the capital area. Li Hongzhang initiated gazetteer projects for both Zhili province (completed in 1885) and Shuntian prefecture (completed in 1886). In his preface to the latter, Li reflected that a gazetteer was required to project the capital prefecture's position of “utmost goodness” (shoushan 首善), a phrase commonly associated with the capital.Footnote 101 According to then-magistrate Luo Xiaoxian 駱孝先, the long interrupted Cangzhou gazetteer project was restarted in the late 1880s in response to a call from Li. But it languished, and about a decade later, Xu Zongliang 徐宗亮 (once again commanded by Li Hongzhang to finally complete the gazetteer) noted that the rise of Tianjin as an international seaport added to Cangzhou's long history as a “hub between north and south.”Footnote 102 Cangzhou was thus incorporated into the renovated “capital region,” now centered in practical terms on Tianjin rather than the imperial capital of Beijing.

By the 1890s, the suffering experienced in the capital region a generation earlier required mention, but mainly as an event giving rise to literary production and ritual revivals. In 1892, contributor Wang Guojun's body was belatedly laid to rest to the southwest of the walled city of Cang. The eminent official Zhang Zhidong 張之洞 (a native of neighboring Nanpi county 南皮縣), wrote a funerary inscription, recognizing Wang Guojun for his role in bringing the walled city's sacrifices to the attention of the court, if only secondarily to his achievements as a second-tier empirical scholar. The 1899 revised gazetteer for Tianjin Prefecture included a volume devoted to war dead (entitled “Martyred Gentlemen and Ladies” xunnan shinü 殉難士女), given that the capital region had been hit hard: “Cang and Yan [suffered] the most, Nanpi and Qingyun after that, Tianjin's Qing and Jinghai counties next.” The names of thousands of Cangzhou residents were directly taken from the earlier Record of Martyrs and closely packed onto one page after another (Figure 4).Footnote 103 The volume's preface concluded that the lists evinced “the blossoming of moral integrity and righteousness (jie yi zhi sheng 節義之盛)” in the postwar era. In other words, the re-centered capital region's outpourings of poetic and ritually pious commemorations now connoted more valor than the suffering they described.

Figure 4. List of Cangzhou Dead, from Revised Tianjin Prefecture Gazetteer (1899). Source: Chongxiu Tianjin fu zhi (1899), 53.23b–24a.

Conclusion

Following the dissolution of the Taiping Northern Expedition in 1855, the imperial capital of Beijing and communities in the surrounding “capital region” ended their phase of the Taiping War. In the capital, which had escaped a direct attack, the executions and ceremonies struck a celebratory tone. In outlying areas that suffered violence the mood was more somber. These communities erected shrines, buried corpses, and rebuilt infrastructure. They also wrote histories of local defense efforts and collected records of the war dead. Across the region, rumors surged in correspondence and in talk, and a few privately written histories were written to describe the calamitous events. Wartime disruption continued in both local and imperial contexts, with upsurges of banditry, decrepit infrastructure, and a population in crisis.

Cangzhou's circumstances invite reflection on the temporality and strategic nature of commemoration. The timeline for commemoration in Cangzhou was interrupted, not seamless, and took place over decades. In pursuit of recognition, Cangzhou elites carried their records to Beijing and circulated their writings through their social networks. They did so in the 1850s seeking court acknowledgement and assistance, in the 1860s seeking inclusion in postwar records, and in the early 1880s seeking broader recognition and financial investment. In the mid-1850s the Record's compilers had sent their documents southward, to connections forged by locals holding offices in Shandong and Jiangnan. These links reprised Cangzhou's historic links south along the Grand Canal. By the early 1880s, they looked to their immediate north, building on connections with Tianjin poets and officials.

Above all, the protracted war in the south provoked uncertainty in the north. In the capital region, projects to symbolically conclude the northern phase of the Taiping War and remember local sacrifices began about a decade before the recapture of Nanjing in 1864. The people of Cangzhou collected bones, wrote poems and essays, and compiled extensive records of the dead. In Cangzhou and elsewhere, locals strategically centered sanitized versions of wartime events, perhaps in expectation of some future reckoning. They connected local actions to the broader project of capital defense. However, after 1855, the rebellion's impact continued and even intensified in central and southern China, making the defense of Beijing seem less consequential. For this reason, underlying the capital region's strategic localism was uncertainty about the place of the capital region in the larger history of the war—and the capital's role in handling the prospective postwar to come.

Competing interests

The author acknowledges none.