From the start of the Reformation movement in England, contemporaries were quick to conclude that a break with the Roman Catholic Church and the adoption of Protestantism entailed a profound reappraisal of the place of visual imagery in worship and devotional life. Accordingly, religious change prompted a great deal of serious and sustained soul-searching about the characteristics of permitted imagery, the contexts, and locations in which it might (and might not) be allowed, and the nature of its use. In this article, we are concerned with the complexity and nuance of the relationship that evolved between Protestantism and the visual arts in post-Reformation England, building upon a wave of recent historiographical interest in the enduring and renewed role of the image in processes of religious reform.

The visual arts have long been seen as a key component of the success of the Lutheran reformation in Germany.Footnote 1 Important edited collections have addressed the impacts of reform across the early modern world, pointing up varying degrees of tolerance about the relationship between art and piety and showing how religious change could both stimulate and curb artistic production.Footnote 2 However, England has occupied a somewhat marginal and opaque position within this wider literature. In part, this is the result of an art historical focus on the fine arts produced by acknowledged masters such as Albrecht Dürer and Lucas Cranach and an associated emphasis on artistic quality that finds little to no value in English vernacular crafts.Footnote 3 A lack of appreciation of the extent to which the visual arts not only survived but evolved and even thrived under the pressures of reform also reflects the distinctive trajectory of the historiography of the English context, in particular the influential thesis put forward by Patrick Collinson in the 1980s that from about 1580 England was dominated by an iconophobic culture.Footnote 4 This thesis has now been comprehensively refuted by reformation scholars; as Adam Morton has observed, it is now “passé to say that post-Reformation England was not an iconophobic society.”Footnote 5 Yet this conclusion relies upon the aggregated evidence of a widely dispersed literature that focuses on specific categories and media, including portraits, monuments, print, and decorative art.Footnote 6 There is thus still a tendency within a wider scholarship to regard hostility to religious images as a default position, albeit one against which an increasing number of exceptions have been identified.Footnote 7 Furthermore, because critique of the iconophobia thesis has largely been incremental and led by counterexample, there is no comprehensive refutation of the pervasive notion that England was left particularly visually impoverished as a result of the Reformation.Footnote 8 The implication is that English Protestants found a way to stomach some visual arts rather than positively embracing them.

Accordingly, we advance a new model that simultaneously explains why English Protestants had such strong reservations about certain uses of specific images in particular situations while also illustrating in positive terms why other images were actively endorsed for use in a range of civil and religious contexts. Our use of the phrase from rejection to reconciliation therefore refers not only to early modern English Protestants’ reconciliation with the use of religious imagery but also to the way that recent historical scholarship has come to rely upon the visual arts as key evidence in understanding the nature, extent, and impact of religious change.

One difficulty the researcher faces in discerning a positive attitude to religious images in early modern England is distilling the subtle but persistent strain of contemporary approbation on the matter of imagery from a veritable outpouring of vitriol against idolatry. In this article we advance a model for understanding how English Protestants navigated the murky terra incognita of post-Reformation image theory, in order to arrive at informed decisions about what sort of imagery was appropriate, where, and for whom. We do so by highlighting points of both consensus and divergence within a wide range of contemporary discourse. In doing so, we advance the notion that Reformed religion was far from incompatible with visual expression, balancing an established historiographical focus on the negative impulses of reform (denunciation, rejection, and destruction of idols) with a richer understanding of Protestantism's rapprochement with the image.Footnote 9

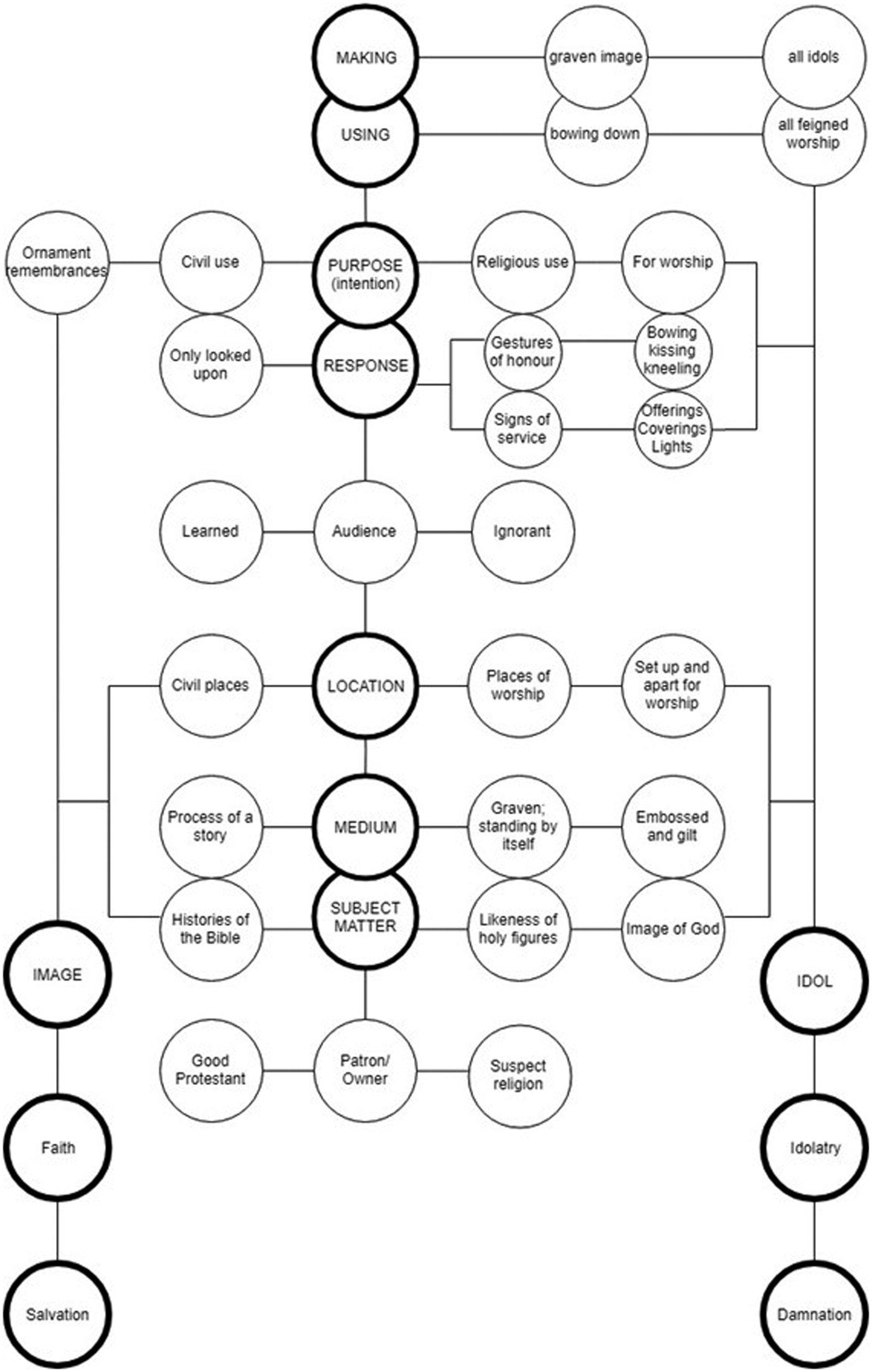

Post-revisionist Reformation scholarship has rightly emphasized the diversity of opinion across various shades of English Protestantism, and these differences explain why images remained such a source of contention in post-Reformation England in this period. Yet Protestants across the religious spectrum were in broad agreement over the criteria to be used in differentiating legitimate, even laudable, images from idols. A degree of consensus in part developed due to the foundational influence of the official homily “Against Peril of Idolatry,” (1562–63), which codified the basic framework within which trajectories of opinion subsequently developed, so that the same terms of reference appear across a wide and often combative discourse.Footnote 10 The devil, of course, was literally in the detail, but while Protestants of different types disagreed (sometimes violently) over how to employ images, contemporary comment reveals a subtle and discriminating approach to issues of use, location, form, subject, materials, patron, and audience that makes plain how proscription was balanced with permission. To be clear, English Protestants did not all share the same position on images; rather, the views that they formulated engaged with and were informed by the same essential criteria. All Protestants rejected idols, but most also recognized that images could have benefits, albeit within a set of painstakingly defined conditions and constraints. In debating the extent of them, commentators followed a shared logic of thinking that amounts to a native English body of Reformed art theory. The core criteria at the heart of this theory are clear to see when presented in graphic form, and to that end we have devised a visual aid modeled on early modern diagrammatic charts as a synthesis of the discussion. In the first half of this article, we present a more nuanced understanding of how the matter of images was debated and negotiated in positive terms, and we envisage the chart as a practical tool and touchstone to inform more sympathetic interpretation of artworks going forward.

Such practical use of the model and chart is the focus of the second half of the article, in which we apply in two case studies the criteria we have identified as central to Protestant art theory. The first study is of a painted commandment board located within a place of worship; the second refers to a carved wood screen originally set in a domestic interior. These examples have been selected as the particularly rich tip of a great iceberg of unattributed provincial craftsmanship—the type of work that flourished in post-Reformation England—and because they allow a rounded demonstration of how the model's criteria can be detected within the design and execution of new production. Detailed discussion of these two artworks, then, is not intended to prove the model by itself but to demonstrate how it can be deployed to inform interpretation of post-Reformation English vernacular arts more broadly. In light of the exceptions and qualifications delineated in the model, we assert that such work should be understood not simply in terms of its didactic or propagandistic purposes but as a profound expression of faith and identity within English Protestantism.

Our focus is the period ca. 1560–1640.Footnote 11 This is the period associated with the “birthpangs,” as Collinson terms it, of English Protestantism, during which processes of adjustment, assimilation, and agitation played out within and across the range of religious identities encompassed (sometimes chafingly) by the established church.Footnote 12 Locating our study within this formative phase of the development of English Protestantism therefore raises the issue of change over time. The various authors and works cited in what follows are intended to reflect the range and diversity of opinion across this eighty-year period. It is not our purpose to provide a comprehensive survey, but we have endeavored to include voices from across the religious spectrum and to span the decades. Of course, commentary on images responded to contemporary political and religious developments, so that sources from the 1560s reflect the active official iconoclasm that followed the Elizabethan religious settlement, and texts from the 1570s and 1580s echo the acrimonious debates between Puritans and Conformists, while comment in the 1630s became especially heated under the polarizing pressure of the Laudian reforms. These shifting contexts serve our purposes here because heightened tensions intensified debate, amplifying the criteria that informed it. The important point is that image theory was worked out within defined parameters, and the criteria under debate remained more or less consistent, as condensed in the chart; it was the emphasis and tone that varied. Realizing the model as a chart may give the impression of a fixed process, but it should be understood as being animated through use; following different routes through the various criteria throws the different emphases and positions of early English Protestantism into sharp relief.

With this article, we make two principal contributions to current work on the cultural impact of the reformation in England: one historiographical, the other methodological. First, in its emphasis on negotiation and reconciliation, it shows how Protestant authors and patrons approached the question of images constructively, thereby providing a systematic and robust counterpoint to lingering assumptions about the inherent hostility of English Protestantism toward the visual arts. Second, the model offers new criteria of judgment through which to approach and interpret the vernacular art of post-Reformation England—a critical framework for analysis that is attuned to the Protestant eye of this period and place. Our emphasis on reconciliation and commendation helps explain the selective nature of iconoclasm and the sites and forms in which new artworks were produced. We therefore offer a more nuanced understanding of the interplay between reformed theology and material production and show that, rather than having been artistically stunted by the Reformation, post-Reformation English Protestantism actively employed the visual arts as aids to faith and devotion.

A New Model

The Protestant need to distinguish between lawful and prohibited imagery stemmed from the fear of idolatry, one of the most heinous sins man could commit. English Protestants’ iconoclastic tendencies are often linked to their rediscovery of the second commandment, against the making and worshipping of graven images—and the Reformed family of Protestants indeed renumbered the Ten Commandments (Exodus 20: 2–17), separating the prohibition against idolatry from the lengthy Catholic first commandment.Footnote 13 But what is less often appreciated is that the whole of the First Table (Exodus 20: 2–11, the first through fourth commandments, which defined the relationship between mankind and God) forbade idolatry and commanded the proper worship of the Lord.Footnote 14 Any failure in these duties was considered to be idolatrous. Any misdirection of the worship due only to God to any other person, object, place, or creature was also idolatry.Footnote 15 What Protestants feared profoundly and consistently was not the image but the sin of idolatry. Greater emphasis on Protestants’ underpinning concern with improper worship helps explain the considerable degree of selectivity and discernment involved in both iconoclasm and the reforming of religious media in the wake of the Reformation.

In discussing the sin of idolatry, commentators provided a wealth of specific guidance on the distinction between idols and acceptable images that amounts to the development of an English Protestant image theory. Discussion of the image is found mainly within commentaries on the commandments, although the issue is also addressed within a wide range of theological tracts and treatises on art produced over the period ca. 1560–ca. 1640. This body of comment encompasses the full spectrum of godly, mainstream, and high church positions within the established church, with views ranging from extreme caution among evangelical reformers through the pragmatic tolerance of conformists to a more relaxed attitude of approbation among religious conservatives. As noted above, this amalgamation of comment is in no way intended to homogenize opinion across the religious spectrum or to mask change over time: indeed, we range widely in order to accommodate the extremes of views that informed and separated forms and currents of Protestantism. Notwithstanding these marked differences in emphasis and tone, there are points of consensus across this body of comment, even if areas of agreement can be hard to identify against the white noise of contemporary religious controversy.

To offer some clarity on this issue, and inspired by the early modern trend for diagrammatic charts to help make plain complex theological positions, we devised a model, graphically realized, that sets out the key criteria that contemporaries thought separated images that could serve to promote faith from idols as a cause of damnation (figure 1).Footnote 16 The model collates and condenses an accumulation of thinking about the role of imagery in Protestant culture over time. The spatial arrangement of the diagram reflects the more contentious and disputed nature of criteria on the right-hand side (the godly were far less forgiving here than their conservative counterparts), while the qualifications listed on the left-hand side were accepted by all. The chart therefore makes plain the structure within which discourse on the image operated and allows us to plot the position of individual authors within this debate.Footnote 17

Figure 1 Diagrammatic chart showing difference between images and idols.

Our model makes clear the criteria by which images were both justified and condemned. The chart reflects the hierarchies and interconnections between and across the various criteria; navigating the question of the validity or otherwise of images in Protestant culture was a carefully negotiated and considered matter. The model can be used today to assess and weigh the criteria systematically on a case-by-case basis, allowing a much more nuanced understanding of how certain images were used and understood as part of the religious cultures of post-Reformation England.

In the following discussion, the model's core criteria are presented as headings, with expansions and qualifiers underlined. This schema permits following the chart against the discussion “by the pointing of the finger.”Footnote 18

Making and Using

In the reformed configuration of the Decalogue, the second commandment prohibited both the making of images (defined as graven and similitudesFootnote 19) and honoring or serving them. Commentators explained that the two actions of making and worship were linked; it was not the making of all images that was forbidden but the making of an idol for the purposes of worship. The influential Calvinist theologian William Perkins defined the command “not make” as “forbidding to make an idol,” while the second part, “bow downe” was meant more generally: “for in it is inhibited all fained worship of God.”Footnote 20 “Simply then wee are not forbidden to make images,” explained the puritan clergyman Andrew Willet, “for there is great use of pictures, in describing of histories, drawing of Cards, and Mapps.”Footnote 21 Osmund Lakes, a Hampshire minister, pointed out that “painting, broydering, moulting, graving and carving be skils not only approved in the Scriptures, but applied also to the service of Gods Temple in the old Testament.”Footnote 22 Perkins too acknowledged that “the arts of painting and graving are the ordinance of God: and to be skilful in them is the gift of God.”Footnote 23 The Arminian cleric Richard Montagu similarly noted that “never man thought, much lesse ever said, that painting and carving of pictures was Idolatry: but lawful trades,” whereas “that which Protestants mislike and condemne in Papists, is not the having, but adoring and worshipping of Images; the giving them honour due unto God; as the ignorant do.”Footnote 24

The challenge for commentators, then, was to define an idol and feigned forms of worship. This created lengthy discussion around the purpose or intention of making an image on the one hand and how an image was used (response) on the other. The second commandment was interpreted by all commentators to speak to much broader issues than specifically image-making and image worship; idolatry did not begin and end with the idol. For Richard Greenham's imaginary catechumen, the second commandment forbade “all inventions and devices of men in the outward worship of God, which be contrarie or besides the written word of God,” including “all corruption in the substance of doctrine, prayer, Sacraments, and discipline of the Church.” Footnote 25 Abused images and statues were simply emblematic of a much more serious concern to ensure the pure worship of God in spirit and truth, according to his word and will. The primary object of regulation was not images but worship.

Purpose

In terms of intended purpose, commentators drew a clear distinction between making images for religious use and civil use. Bishop Gervase Babington, a staunch Calvinist, explained that the best judgment in response to the prohibition of making images “is of them that thinke it lawfull to make pictures of things which wee have seene to a civil use, but not to use them in the Church and for religion.”Footnote 26 Osmund Lakes described how “Images be made for two uses, either civil, for storie, remembrance or ornament: or religious, for worship.”Footnote 27 William Perkins explained that, by civil use, “I understand, that use which is made of them in the common societies of men, out of the appointed places of the solemne worship of God.”Footnote 28 The Calvinist pastor Francis Bunny agreed that the commandment did not forbid all images. Portraits, for example, were perfectly permissible: “For the representation of men or women, whom for their authoritie or other good parts in them wee reverence, or love, is not unlawfull; or if they [images] be made to garnish and beautifie any place, or in any other civil respect, this Commandement is not thereby broken.”Footnote 29 The term civil had various connected definitions in this period. In addition to the limited sense of non-religious or secular. definitions centering around the idea of community were particularly common in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.Footnote 30 These variant definitions included “relating to citizens or people who live together in a community” and “social.” Understanding this range of definitions is important, as the term civil is repeated in various forms in terms of use and location in commentary on images, and a simplistic definition of civil as synonymous with non-religious misses the possibility of its application in the sense of community and social use. The term civil was capacious and could indicate a social or community function, even in a religious space. Gervase Babington therefore noted that “it be tolerable in some mens opinions, and a thing indifferent, to have some sort of pictures in the Church for a civill use, as either for storie and remembrance sake, or for ornament and beautie of that place.”Footnote 31

Religious use, in contrast, had a narrower focus in these discussions and meant primarily “as related to worship.” As John Bossy observes, “religio in classical Latin is a sense of duty or reverence for sacred things,” and while this usage faded during the Middle Ages, it was resurrected by Christian humanists and was common parlance once again by the sixteenth century.Footnote 32 Most commentators therefore elided religious use with “worship,” and accordingly an intention to use images in support of religion in the broader (modern) sense was not necessarily understood as a contravention of the commandment. Some high church clergymen in the 1620s expanded upon the qualification of images as remembrances, to keep doctrine in mind. John Donne acknowledged that “where there is a frequent preaching, there is no necessity of pictures,” but argued that “if the true use of Pictures bee preached unto them [the people], there is no danger of an abuse; and so as Remembrancers of that which hath been taught in the Pulpit, they may be retained.”Footnote 33 Lancelot Andrewes, the anti-Calvinist bishop of Winchester, offered a similar view: “there are other means better and more effectual then pictures to instruct men in the knowledge of Christ, viz. The scriptures and the preaching of the gospel . . . [but] that which is of less use, is not therefore unlawful or of no use at all . . . [so that] To have a story painted for memories sake we hold not unlawful, but that it might be well enough done, if the church found it not inconvenient for her children.”Footnote 34

Response

The issue of purpose was counterbalanced by the question of use, or response. An image might not be intended for worship, but it could become abused by veneration. This resulted in an attempt by commentators to define the nature of worshipful behavior. As Lakes explained, making idols was forbidden, but even more so was worshipping images once made, “and here that also is forbidden in two things, in kneeling or bowing the bodie, and giving any forme of service, to, or before it,” thus separating out bodily gestures of honor and signs of service.Footnote 35 In attempting to describe gestures of honor, William Perkins listed “the bowing of the head, and knee; the bending and prostrating of the bodie; the lifting up of the hands, eyes, and such like.”Footnote 36 Babington defined worshipping of images as “to fall downe before . . . [it], and to do it reverence, capping, knelling, creeping [that is, crawling], crossing, kissing, lighting up Candles to it, and such like.”Footnote 37 In addition to bodily gestures, response to images could be assessed by material context. In defining superstitious worship, the homily “Against Peril of Idolatry” detailed outward signs of service as “[to] set up candles, burn incense before them, offer up gold and silver unto them, hang up ships, crutches, chains, men and women of wax.”Footnote 38 Perkins quoted Isaiah 30.22 to argue that “all reliques and monuments of idols” should be abolished along with them, meaning casings, coverings, and cloths.Footnote 39 Alternatively, images that did not attract signs of honor and were only looked upon, with no evidence of being venerated, could be permitted. This distinction was explained by Simon Birckbek, vicar of Gilling in Yorkshire, in his 1635 defense of the English Church: “[F]or we mislike not pictures or Images for historicall use and ornament; now this distinction and disparitie between making and worshipping, is confirmed by the example of the Brazen Serpent, made by Gods owne appointment; for when the same was onely made, and looked upon, it was a Medicine, when it was worshipped, it became a poison, and was destroyed.”Footnote 40

Behavior in response to images was contingent on proper understanding, meaning that the nature of the intended audience was also a vitally important consideration. From the beginning, reformers highlighted the particular danger of image worship among the unlearned, raising the contextual issue of audience. The homily explained that images were worshipped “of the unlearned and simple sort shortly after they have been publicly so set up,” though ultimately by “the wise and learned also.”Footnote 41 Francis Bunny judged that “it is very hard to finde any among the simple, who if they confess the truth, do not kneel and pray to the image itself.”Footnote 42 Babington observed that only a “fewe . . . that have learning can distinguish betwixt the image, and the thing represented thereby.”Footnote 43 The leading puritan clergyman John Dod commented upon the fact that human nature was particularly “prone and inclinable to this sinne” of idolatry, “for as the looking upon an harlot will infect one with bodily uncleannesse, so also the looking upon an Idoll will pollute an ignorant & blind heart with Idolatry, & bring it to confusion.”Footnote 44 Legitimate images, therefore, must be readily distinguishable as artificial representations to avoid confusion (see the discussion under “Medium,” below), but such comments also suggest the need for general instruction in the proper use of images (the purpose of these various publications) and a learned and watchful eye kept on those exposed to the image (see patron, below).

Location

Commentators recognized that the nature and function of a space directed and influenced behavior, putting pressure on the question of location. Most authors played it safe, declaring that images in places of worship presented too great a lure and should be avoided. James Calfhill, a leading Calvinist in the first decade of Elizabeth's reign, agreed with the Homily in stating that “Images for no superstition, Images of none worshipped, nor in danger to be worshipped, are in deed tolerable; but images placed in publique Temples, can not be possibly without danger of worshipping, and therefore are not to be suffered.”Footnote 45 There is, however, some indication that an image's nature and spatial positioning within places of worship played a factor in assessing risk. Willet mentions images “set up aloft” and (as discussed below under “Medium”), images that were set apart from other decorations suggested special treatment—that is, signs of honor, whereas imagery on a church wall or in windows might be considered benign.Footnote 46 The general prohibition on images in places of worship could also be mitigated by subject matter, so that edifying narrative images of non-sacred figures were distinguished from idols.

What was unacceptable in places of worship could be perfectly permissible in private or civil places, placing images in a domestic or social context largely outside the proscriptions of the second commandment. In a text published in 1579, the moderate puritan William Fulke argued that “the painting of stories in clothes or galleries &c.,” “were in no use of religion, and without all daunger of worshipping, therefore not prohibited.”Footnote 47 The consensus of opinion agreed with this and the similar line adopted by William Perkins, who was opposed to biblical images in churches but found them acceptable elsewhere: he explained that one of the lawful uses of images was “when images are made for the beautifying of houses either publike or private, that serve only for civill meetings” (meaning social gatherings).Footnote 48 Of course, religious behaviors were very much a central part of domestic life: the household should be a “little church.”Footnote 49 It is necessary therefore to be wary of equating private or civil locations with secular spaces or activities.

Medium

Medium (form and materials) was considered relevant to the debate because reformers recognized that the degree of realism and richness of an image affected viewers’ response.Footnote 50 The Elizabethan homily “Against Peril of Idolatry” explained that “men are not so ready to worship a picture on a wall, or in a window, as an embossed and gilt Image, set with pearl and stone. And a process of a story, painted with the gestures and actions of many persons, and commonly the sum of the story written withal, hath another use in it, then one dumb idol or image standing by it self.”Footnote 51

The Homily therefore distinguished between narrative stories painted on walls or in windows and images of holy figures standing alone. The description of “one dumb idol or image standing by itself” indicates three-dimensional carved sculpture in the round. The literal interpretation of “graven images” in the second commandment as “carved” and “cast” images provided another restriction on the range of images open to attack. Lakes translates from the Hebrew as “any forme graven or carved in mettall, stone or wood,” though he explains that not all such graving in general is forbidden but only representations of God (whether intended for the true God or not).Footnote 52 Similarly, embossed and gilt images, made of precious metals, “brasse, golde, silver, or such things” that were gilded or enriched with ornate clothing and precious stones, suggested special qualities that would encourage admiration, a slippery slope toward veneration.Footnote 53 The homily condemned “excessive decking of images and idols, with painting, gilding, adorning, with precious vestures, pearl, and stone.”Footnote 54

Subject Matter

Subject matter or iconography was also assessed according to the risk it posed in prompting worship. Calvin stated that visible representations that are “historical, which give a representation of events . . . are of some use for instruction or admonition.”Footnote 55 The majority of commentators agreed with this view, also expressed in the official Homily, and most distinguished between narrative images, which represented biblical histories or stories, and images of individual figures isolated from a narrative context. Accordingly, William Perkins held histories of the Bible “to be good and lawful: and that is, to represent to the eye the acts of histories, whether they be human or divine; and thus we think the histories of the Bible may be painted in private places.”Footnote 56 Another way to distinguish between good and lawful images, and idols, was therefore the matter of scriptural fidelity; if the image could be justified as a literal depiction of historical events as recorded in the scriptures. Images with invented elements that went beyond descriptions provided in biblical texts were identified as false and lying deceptions that directed believers away from God's truth. As James Calfhill explained in 1565, “[S]ince our Religion ought to be grounded upon truth, Images which can not be without lies ought not to be made, or put to any use of Religion.”Footnote 57

There was general acknowledgment that depiction of histories could inspire and elevate; in Defence of Poesy, published posthumously in 1595, Sir Philip Sidney compared the art of poetry with the painter “that should give to the eye either some excellent perspective, or fine picture fit for building . . . or containing in it some notable example as Abraham sacrificing his son Isaac, Judith killing Holofernes, David fighting with Goliath.” Sidney used these three biblical stories to argue that “figuring forth good things” could be beneficial: “[I]t is a good reason, that whatsoever, being abused, doth most harm, being rightly used . . . doth most good.”Footnote 58 In other words, Sidney accepted that pictures could be harmful if abused (by worship) but could also do good if used correctly to edify and inspire.Footnote 59 The amateur artist Thomas Trevelyon created a huge illustrated miscellany in 1616 that includes numerous biblical images including the Nativity and Crucifixion. In a rare comment on the function of such images, he explained, “The matter handled in this booke is three folde, historicall, propheticall, and evangelicall, the first teacheth examples, the second manners, and the laste a spirituall and heavenly institution.”Footnote 60

Statues and carvings that presented likenesses of holy figures—God the Father, Christ, the Virgin Mary and Saints—were deemed especially dangerous because they were so beloved by believers and prompted demonstrably incorrect behavior. Here again, the Homily against Idolatry provided the lead: “the greater the opinion is of the maiestie and holiness of the person to whom an Image is made, the sooner will the people fall to the worshipping of the said Image. Wherefore the images of God, our Saviour Christ, the blessed virgin Mary, the Apostles, Martyrs, and other of notable holiness, are of all other images most dangerous for the peril of Idolatry, and therefore greatest heed to be taken that none of them be suffered to stand publicly in Churches and Temples.”Footnote 61

Babington states that the purpose of the second commandment “is chiefly to forbid all pictures of God.”Footnote 62 Reformers unanimously agreed that images of God the Father were forbidden in any context because “He never was seene, and therefore can not be painted or pictured like any creature, but with a breach of this [second] commandment.”Footnote 63 John Dod described the most dangerous and damnable images as “such as are made to represent anie of the three persons in trinitie, the father, the sonne & holy ghost: and these, whatsoever pretence and purpose man hath in setting them up, are simply evill.”Footnote 64 Any attempt to visualize in material form the unimaginable mystery of the Godhead was, according to Peter Barker in his commentary on the commandments, an “injury to his divine nature, and is no likeness of God, but onely an imagination of man.”Footnote 65 This inability to conceive of, let alone represent, the divine meant that not only the figure of God the Father but the other elements of the Trinity—the figure of Christ on the cross and the dove of the holy spirit—were also flawed. “It is a wicked thing,” stated Dod, “to make an Image of CHRIST, seeing that we can in no way resemble that which chiefly makes him Christ.”Footnote 66

While many authors writing during the long post-Reformation period agreed that the image of the risen Christ was forbidden, some asserted that depicting him as man prior to the crucifixion was acceptable as long as it was used only as an illustration of historical events. Even William Perkins took this view, arguing that “it is not unlawfull to make or to have the Image of Christ, two caveats being remembered. The first, that this Image be onely of the manhood: the second, that it be out of use of religion. For if otherwise it be made to represent whole Christ, God and man: or, if it be used as an instrument or a signe in which, and before which men worship Christ himselfe, it is . . . a flat idol.”Footnote 67 At the other end of the religious spectrum, Lancelot Andrewes considered it “not unlawful to paint or make any portraiture of Christ in his humane nature, as at his passion &c. Provided, no religious worship be given to it.”Footnote 68 Henry Peacham, poet and writer, followed this moderate line of official policy in directing his intended readers of gentlemen, tradesmen, and artificers that “Neither by any meanes may the picture of our Saviour, the Apostles and Martyrs of the Church be drawne to an Idolatrous use, or be set up in Churches to be worshipped.” But, he added, echoing the views of churchmen cited above, “that pictures of these kindes may be drawne, and set up to draw the beholder ad Historicum usum, and not ad cultum, I hold them very lawfull and tolerable in the windowes of Churches and the private houses, and deserving not to bee beaten downe with that violence and furie as they have beene by our Puritanes in many places.”Footnote 69

A final contextual qualification included in the model is rarely commented upon and yet, as will become evident, was clearly an important consideration in assessing the likely use or misuse of an image. The religious credentials of the patron/owner of an image could be a first or final consideration in calculating purpose or intent. Thus, a known papist could not be permitted an image that would otherwise be judged acceptable, even beneficial, for good Protestant viewers.Footnote 70 Meanwhile, an image that might be judged a potential idol in another context could be viewed positively if authorized by the strict godly leanings of its patron. In general, reforming divines emphasized the principle, as outlined by Paul in his Epistle to Titus, that “unto the pure are all things pure, but unto them that are defiled, and unbelieving, is nothing pure, but even their minds and consciences are defiled.” As the marginal note (a) to the 1599 Geneva Bible observed, “[P]urity consisteth not in any external worship . . . but in the mind and conscience.”Footnote 71 Election rendered the works of the regenerate acceptable to God, but the “ordinary works” of the unregenerate were “sinfull and odious in Gods sight.”Footnote 72

Our model of guidance on the matter of images, condensed in the diagrammatic chart (figure 1), therefore highlights the key nodes to be considered in relation to images and identifies both the core areas of consensus and the potential areas for disagreement. Picking up on Peacham's conclusion that religious pictures could be lawful and tolerable in churches and domestic houses if not made and put up to be worshipped, below we offer two examples of artworks that demonstrate how such discourse relates to practice. We show that while these examples may push at the boundaries of the model, on the balance of its various criteria, Protestant image theory could be very accommodating.

Case Study 1: Picturing the Decalogue

Our first case study relates to an almost extinct genre of early modern English material culture—painted depictions of the Ten Commandments in churches. The choice of this case study relates in particular to the argument that Reformed Protestants were especially hostile to religious imagery in ecclesiastical spaces, and to the erroneous suggestion that the visually rich interiors of medieval churches were transformed following the Reformation into plain whitewashed boxes.Footnote 73 On 22 January 1561, Elizabeth I issued a royal order “that the tables of the commandments may be comlye set up, or hung up in the east end of the chauncell” of every church in England, “to be not only read for edification, but also to give some comlye ornament and demonstration, that the same is a place of religion and prayer.”Footnote 74 While every one of England's approximately nine thousand parish churches would have complied with this order, repeated in numerous visitation articles and injunctions, only about thirty examples survive from the period ca. 1560–ca. 1660 down to the present day.Footnote 75 While all are significant, two are especially intriguing, because they contain painted narrative scenes from scripture and therefore challenge received wisdom about the place of religious art in the post-Reformation English parish church.Footnote 76 This case study focuses on the earlier of the two boards, from the parish church of All Hallows, Whitchurch, Hampshire, dated 1602 (figure 2).Footnote 77

Figure 2 Commandment board, All Hallows Church, Whitchurch, Hampshire, dated 1602.

In large part, the Whitchurch Board adheres to the expectations about post-Reformation religious art outlined by our model. The images are drawn from the historical books of the Old Testament and are narrative in nature; there are no images of persons who might easily become the objects of idolatrous veneration. The other truism of much recent scholarship on the relationship between Protestantism and the reformed visual arts in England, however, is that they were located primarily in civil (especially domestic) spaces.Footnote 78 In other words, we do not expect to find religious art in church, and yet here it was in Tudor Whitchurch. The significance of this work alongside several other examples suggests the existence of a common visual language for illustrating the Ten Commandments in post-Reformation England, which might be equally as at home in a domestic space as inside the ecclesiastical space of the parish church.Footnote 79

This visual language is explored in more detail here. Ten of the images on the board relate directly to the Decalogue with each picture illustrating the breach of one of God's commandments, supported by a caption referencing a story drawn from the Old Testament. The scheme of imagery is presented in table 1.

Table 1 Biblical Captions on the Whitchurch commandment board

Two questions arise: How did these particular images end up on the walls of at least two churches? And how could such figurative images be newly erected in a place of worship? The second of these questions is more easily dealt with, thanks to the nuanced perspective established by our model. As we have shown, Protestants subjected visual images to a whole series of tests in order to determine whether they were idolatrous, harmless, or indeed positively beneficial. The Whitchurch commandment board featured painted (not graven) images and did not depict God, save for the divine hand and sleeve reaching out of a cloud to hand the stone tablets to a kneeling Moses. The use of these images was not religious in the sense of for worship; rather, it was civil, in the sense of providing the community space of the parish church with (in the words of the queen) both ornament and demonstration that this was a place of religion and prayer. The board was therefore compliant with the spirit of the Elizabethan injunctions, even if it took a creative approach to fulfilling them. The location of the images inside the church makes their ability to pass the remaining criteria outlined by the model particularly important, for what was acceptable outside the church was not automatically acceptable within it. Indeed, the position of the board was likely at the east end of the church behind the communion table, where it would have acted as a backdrop for the receipt of the Eucharistic bread and wine for kneeling communicants.Footnote 81 Such a focal position, set apart and in close proximity to the sacrament, was a red flag for Protestant commentators. The subject matter, however, in the form of narrative scenes from the Old Testament, was unimpeachable. Furthermore, the stories and figures depicted were not worthy exemplars to emulate (with the potential to slide into adoration) but instances of the notoriously wicked receiving divine punishment for their egregious sins. As such, the worshipping parishioners could be put in mind of and guided by the biblical histories displayed, without any hint or danger of idolatry or improper worship. Indeed, insofar as they underscored the importance of striving to live a moral and religious life in accordance with God's commandments, these images with their identifying scriptural citations and explanatory captions were positively edifying. They reminded believers that the wages of sin were death, and that true faith in, and knowledge of, the justice and mercy of God was the only possible route to salvation.

Making judgments about the credentials of the patron of the board is difficult. Unfortunately, the churchwardens’ accounts for the parish, which would contain details surrounding the commissioning of and payment for the paintings, do not survive. The likelihood, however, is that it was paid for out of communal funds by the serving wardens on behalf of the parish.Footnote 82 The vicar of All Hallows Whitchurch at the time was Peter Porter, an otherwise unremarkable figure who was appointed in 1591 and died in 1605.Footnote 83 The commandment board was not entirely unproblematic from a pedagogical and theological standpoint, for by presenting such extreme examples of wickedness, the boards could be read as suggesting that sin was something that might be avoided, whereas Calvinist theology asserted that all men and women were born sinners and broke the commandments regularly in thought, word, and deed.Footnote 84 But in the context of the parish church, where its relatively simple visual message was carefully framed and contextualized in service time by the minister performing the liturgy, reading from scripture, or preaching a sermon or homily, the Whitchurch commandment board had the potential to act as a powerful tool of religious and moral edification.

Answering the question of how these images in particular came to adorn a rural English parish church is more complex. Suggesting an answer helps to expand the field's knowledge of the extent to which biblical images and motifs circulated widely throughout post-Reformation Europe, moving across borders and confessions and between different types of printed and painted media with surprising frequency and ease. It also forces scholars and students of the period to revisit the supposed insularity of vernacular visual art and acknowledge the extent to which the tools of English Protestantism absorbed the artistic expression of European religious cultures. Like many aspects of post-Reformation religious culture, the Whitchurch commandment board had its origins in the medieval past.Footnote 85 These medieval precedents were crucial in heavily influencing what became a lively Protestant tradition in the sixteenth century, beginning with Lucas Cranach's Haustafel, a series of woodcuts demonstrating the breach of the Ten Commandments.Footnote 86 While Cranach's choice of biblical episodes dominated Lutheran publications, a number of illustrated Dutch prints continued to vary the exempla, including illustrations by Lieven de Witte, Maarten van Heemsecke, and Maarten de Vos.Footnote 87 De Vos advertised his Decalogue as containing examples of “the severest punishments for those who have broken the commandments,” which led him to reach back to brutal medieval exempla overlooked in Cranach's and later Dutch and German prints, such as the shooting of Ahab for his coveting of Naboth's vineyard and Joab's killing of Amasa. Both these examples feature in the Whitchurch scheme, although de Vos's woodcuts provide only six out of ten matches overall.Footnote 88

To identify the exact scheme and iconography found at Whitchurch requires a lateral move. Continental prints had a huge influence on art and decoration in Elizabethan and Jacobean England, not simply through straightforward copying but also from artists drawing on and borrowing from a wide range of sources.Footnote 89 For example, the composition of the image of the Israelites worshipping the golden calf from the Whitchurch commandment board is similar to a 1587 print made by Adriaen Collaert after Maarten de Vos and published by Philips Galle as part of a series on the Decalogue.Footnote 90 However, the images at Whitchurch appear to have been drawn not only from illustrated sequences of the Ten Commandments but from other illustrated Old Testament histories as well. Gerard de Jode's Thesaurus Sacrarum Historiarum veteris testamenti appears to be the only known printed source for the image of Pharoah and his host consumed by the churning waters of the Red Sea, and de Jode also provides good matches for the images of the death of Absolon, Phinehas's execution of Zimri and Cozby, and Achan's theft of the Babylonish treasure (figures 3 and 4).Footnote 91 Several of the images may also have had a source rather closer to home: the illustrations for the 1568 and 1572 editions of the Bishops’ Bible, although these pictures too had a complex history in Catholic and Protestant publications on both sides of the English Channel.Footnote 92

Figure 3 Detail of Pharaoh and his host being consumed by the Red Sea, from All Hallows Whitchurch commandment board.

Figure 4 Gerard de Jode, The Crossing of the Red Sea, in Thesaurus Sacrarum Historiarum veteris testamenti (1585). © The Trustees of the British Museum.

The design and execution of the Hedgerley commandment board therefore appears to have tapped into an extensive visual vocabulary of Old Testament imagery, a complex and hybrid culture that included English and continental European work originating from a range of different genres, artists, and confessions. This commission was carefully and thoughtfully custom made from a diverse range of sources rather than relying on the copying of a single print or even a set of prints. The reproduction of Dutch engravings in the decoration of domestic houses was ubiquitous, so it should not be surprising that these uncontroversial Old Testament narratives of wicked sinners receiving providential punishment for flouting the laws of God might wind up in a different format in an ecclesiastical space. This was a considered commission for a civil purpose, making use of a range of sources, and while religious imagery was always treated carefully, it was entirely possible to place such pictorial art within the parish church itself, provided that it adhered to the criteria outlined in the model above.

Case Study 2: Comely Ornament and Demonstration

At the west end of the Church of All Saints in Curry Mallet, Somerset, is a carved wooden screen dating from the first half of the seventeenth century. It presents a scheme of religious imagery that includes Adam and Eve, Moses with Aaron and Hur, the Nativity, and the Crucifixion. Four supporting caryatids at the base of the structure depict Saint Paul, Mary Magdalene, the Virgin and Child, and Saint Peter, while at the top are four Virtues (figure 5).Footnote 93

Figure 5 View of the carved wood screen in the Church of All Saints, Curry Mallet, Somerset, ca. 1630.

Religious imagery in large-scale decorative fixtures has long been overlooked by art historians and historians, in part because of its vernacular style. Nicholas Pevsner, for example, in his Buildings of England series, recorded this piece of work in his entry for the village in 1958 but described it as “robust and illiterate.” He went on to object to the nature of the four caryatids, who “are not just decorative maidens, but important persons who should not have been degraded to such a function.”Footnote 94 Pevsner's verdict is symptomatic of a wider scholarly confusion around such imagery. Viewed as an ugly and aberrant anomaly, the screen has been excluded from consideration within critical scholarship just as it has been ousted from its material setting. Letters from the 1920s when the screen was donated to the church state that the screen was made for the dining hall of the neighboring Manor House, occupied from the sixteenth century by the Pyne family. It was installed in the Pyne chapel after 1926 before being relocated again in 1949 when it became part of the war memorial in the west tower.Footnote 95

If the screen had been original to the church, this work would defy our model in its depiction of holy personages. As noted above, the homily “Against Peril of Idolatry” specified that images of the Virgin and Child and Christ on the cross were forbidden in places of worship, and this prohibition was widely accepted thereafter. The work moves back within the bounds of our model because it was originally intended for the civil purpose of ornament in a domestic setting. Nevertheless, as discussed, many commentators worried about the legitimacy and potential abuse of images of Christ even in a civil context.Footnote 96 The subject matter therefore raises questions about how such imagery could be reconciled with Protestant anxieties about idolatry. In what follows, we interrogate connections between the setting, medium, design, and detail of the imagery according to the various criteria incorporated within our model. We start by considering the religious inclinations of the patron.

Two coats of arms combining Pyne and Hanham within the design identify the patron as the John Pyne who inherited Curry Mallet Manor from his grandfather as a minor in 1609.Footnote 97 His mother was the daughter of Thomas Hanham, and in 1629 John married into the same family, a marriage that was controversial: he eloped with his cousin, Eleanor Hanham. The date of the marriage, which is celebrated in the design through the second heraldic shield and in a roundel with profile faces of a man and woman, corresponds with the style of the carving, putting its date of production around 1630.Footnote 98

John Pyne trained as a lawyer and served as a politician. Presbyterian in religion, in the 1630s he was regarded as one of the rigid party against the king. By 1645, he headed an extreme parliamentarian faction in Somerset, although he avoided involvement in the king's execution and refused any office under Cromwell. At the Restoration, he took the oath of allegiance but was debarred from holding public office. He was several times imprisoned on suspicion of plotting but lived out his life at Curry Mallet.Footnote 99 He died in 1678, having asked to be buried silently at night without any outward pomp or usual ceremony.Footnote 100 The stipulation for a quiet and unceremonious burial rejecting outward pomp underlines Pyne's puritan beliefs. So, how could he qualify having this artwork with religious scenes made to decorate his house at Curry Mallet, and what was his purpose in doing so?

The Curry Mallet woodwork was said to have come from the dining room of the manor house—so a hall, parlor, or great chamber, the grand reception rooms of the seventeenth-century country house. The form of the work suggests it was a fireplace overmantel, as the reverse is entirely plain, indicating it was affixed to a wall. Its large size (9′ 6″ x 6′) suggests the great hall as the most likely setting. As discussed earlier, civil use, including as ornament, was one of many stated exceptions to the prohibition of religious imagery. Yet how can such an extravagant piece of decoration be reconciled with Pyne's rejection of outward pomp for his funeral? Domestic decoration was not an optional luxury for people of status in early modern England: it was an essential and expected element in the fashioning of identity, providing a medium for the public demonstration of wealth and social position.Footnote 101 Meanwhile, large-scale fixtures and furnishings, especially wooden items of furniture such as tables, cupboards, and bedsteads, were understood and described in wills of the period as “standards,” indissolubly linked to the built fabric of the household and part of its material inheritance to pass on to future generations forever.Footnote 102

The obligation to display status through material fixtures and furnishings coupled with ideas about furniture as establishing or augmenting a house—understood as a social institution—helps explain the form, content, and timing of this piece. Redecoration and acquisition of core items of furniture usually occurred in relation to extraordinary events like marriage or through inheritance. The symbolic connection between standards and rites of passage in the life cycle was often made explicit in the design and decoration of individual items. Although Pyne inherited the manor in 1609 at the age of nine, it would have been at the point of his marriage and his elevation to head of household that the manor became appropriate as a site of display. The combination of heraldry and religious imagery communicates his identity as a pious gentleman householder, a status achieved through his marriage. The religious scenes and figures are therefore excused, to a considerable extent, by their civil location and purpose in a domestic hall, where they serve as ornament appropriate to the identity of the owner, a patron with impeccable Protestant credentials.

The next qualification in our model concerns medium. The piece is carved in high relief but is not fully rounded sculpture, and it presents a scheme of imagery rather than a single figure. The elaborate, balanced design means that no component part has particular prominence. In fact, the disposition of the integral parts could be argued to encourage a roving eye. Where is one supposed to start viewing this work? Is there a logical sequence? As shown in figure 6, it would seem sensible to start at the top with Adam and Eve's Fall (1), across to the Expulsion (2), which shows the consequence of this sin, down to the Nativity (3) as the birth of the Savior, then across to the Crucifixion (4), which redeems the Fall as depicted above. But then the eye is required to move on and up again to view the Moses, Aaron, and Hur scene (5), which was necessarily skipped over before. This arrangement suggests circular modes of viewing. The scene of Moses, Aaron, and Hur (out of biblical chronology) is important as it stops the eye from resting on the Crucifixion scene. The design, therefore, appears to discourage gazing on a single part, resisting the prolonged and engaged viewing associated with idolatry.

Figure 6 Carved wood screen in the Church of All Saints, Curry Mallet, Somerset, ca. 1630, with labels identifying the nature and placement of imagery.

In addition to forming a process of a story or being part of a wider scheme, the biblical scenes conform to the requirement of scriptural fidelity. The Crucifixion image (figure 7) is not a moment out of time (like a rood) but a specific historical incident—the moment when Christ's dead body is pierced by the spear (John 19:34).Footnote 103 While the five biblical scenes within the scheme relate to specific episodes as described in scripture, they are not narrative in a strict sense because they contain insufficient information to tell the whole story; rather, they evoke stories that were already highly familiar. They can be described as synoptic images in that they present the condensed essence of the subject matter to stand as a general synopsis of the whole.Footnote 104 In their striking, stylized, visual economy, these scenes referred the viewer efficiently to the core doctrinal concepts they represent, thereby acting as reminders, one of the key approved civil functions of images. The presence of this sort of imagery within the post-Reformation household can be understood as an attempt to sustain attention on spiritual endeavor, even during the toil and hubbub of domestic life. As reminders of the divine plan, these synoptic images could offer a sense of focus and comfort, but their bald form meant that they would not distract or divert attention from necessary tasks.

Figure 7 Crucifixion (left) and Nativity (right), details from the carved wood screen in the Church of All Saints, Curry Mallet, Somerset, ca.1630.

In its function as remembrance, a particular visual detail of the imagery becomes especially meaningful. The scenes of the Nativity and Crucifixion are framed by curtains (figure 7). This device emphasizes a theatrical quality akin to the discovery space of the Elizabethan playhouse stage and indicates a revealed view on a different temporal dimension. A similar device can be seen in other artworks of the period, where pulling back the curtains reveals the effigy of the deceased. Examples include the large painting of the Saltonstall family in the Tate, ca. 1641, and the monument to Sir Eubule Thelwall, 1630, in Jesus College Chapel, Oxford (figure 8).Footnote 105 These comparable artworks highlight the memorializing function of the imagery; the curtains make it clear that these are mere representations, viewpoints onto something out of and beyond the present time. The convention ensures that there is no chance of suspension of disbelief, of mistaking the images for the prototype and therefore being moved to idolatry.

Figure 8 Funeral monument to Sir Eubule Thelwall, 1630, in Jesus College Chapel, Oxford. Photo credit: Jesus College, University of Oxford.

This distancing strategy might also explain how depictions of saints and the Virgin Mary could be permitted. Their role as caryatids, with headwear of flora and fauna, undermines any sense of realism (figure 9). In this context, there is little danger that these figures might encourage devotional gestures of worship. Other examples of fireplace overmantels have the same balance of male and female gendered caryatids, but these are often semi-clad talismanic figures reflecting traditional associations with fertility and fecundity appropriate for their role as household objects connected with rites of passage (marriage and procreation). The depiction of male and female saints supporting the biblical scenes is more appropriate to the overall tenor of this scheme.Footnote 106 The keys held by Saint Peter may seem especially surprising given their association with papal authority.Footnote 107 In this context, however, the keys appear as the saint's identifying attribute with secure scriptural basis; the marginal notes of the 1599 Geneva Bible gloss Jesus's words in giving to Peter the keys of heaven in Matthew 16:19 as a “metaphor taken of stewards which carry the keys: and here is set forth the power of the ministers of the word.”Footnote 108 As a metaphor, the keys (along with the object attributes of the other disciples) would not have been considered objectionable as long as the imagery conformed to the other criteria discussed here. Indeed, the acceptability of such imagery in official Protestant contexts is underlined by the fact that Saint Peter is depicted with his keys on the title page of the 1611 King James Bible.Footnote 109 A final consideration is the Moses, Aaron, and Hur scene, which seems unconnected with the rest of the scheme (figure 10). This image, illustrating Exodus 17:12, shows Moses lifting up his hands, supported by Aaron and Hur, to invoke the power of God in the battle against the Amalekites; all the time that his hands remained raised, Joshua's army prevailed. This story had been interpreted from the earliest days of Christianity as a type of the Crucifixion because Moses's saving gesture in spreading his arms was compared with Christ's sacrifice on the Cross. Early modern commentators, however, focused on Moses's action as an example of the power of prayer. For George Abbott, Moses holding up his hands against the Amalekites served as an example of the prayer of a righteous man prevailing.Footnote 110 It is as an example of prayer that the scene is deployed in the lower section of the title page to Lewis Bayly's blockbuster devotional handbook The Practise of Pietie (1613) (figure 11), which also draws the comparison between Moses and Christ (as the rock upon which Moses's arm rests).

Figure 9 Virgin and Child (left) and St Peter (right), details of two of the caryatids, with headwear of flora and fauna, from the carved wood screen in the Church of All Saints, Curry Mallet, Somerset, ca. 1630.

Figure 10 Moses, Aaron, and Hur (illustrating Exodus 17:12), detail from the carved wood screen in the Church of All Saints, Curry Mallet, Somerset, ca.1630.

Figure 11 Illustrated title page to Lewis Bayly's The Practise of Pietie, 1618 edition. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

An unusual detail in the carved version is the two orbs with crosses, a symbol of monarchy, which seems out of place in the context of the religious iconography. This orb is also a symbol associated with the Salvator Mundi, an image of Christ as Savior of the World, with his hand(s) raised in blessing. As an invented concept of Christ in his divinity, this iconography fell foul of Protestant proscriptions, but the Salvator Mundi did endure in a heraldic mode as the Bishop of Chichester's arms, the subject of a sermon by Thomas Vicars published in 1627.Footnote 111 The additional detail of the orbs coupled with Moses's raised hands might therefore suggest a visual correlation with Christ as Salvator Mundi, so that this image at the apex of the scheme represents both prayer and salvation. As such, it encapsulates the essence of the scheme's function in the great hall of a puritan patriarch, the room synonymous with the character of this household, where its godly community could come together for daily prayer.Footnote 112

Close analysis of this artwork, interpreted in conjunction with our model of Protestant image theory, allows recognition of its function and operation within a puritan household. A necessary demonstration of status by a young husband claiming and enhancing his domestic inheritance, this ornament also demonstrates his religious commitment as a godly patriarch. As a display of piety that would reinforce spiritual endeavor, the work is carefully and cleverly conceived in whole and in part. From the overall design, which encourages taking in the entire scheme rather than focusing on individual figures, to the little details such as the saints’ floral headgear and the curtains, there are visual cues that these images should be treated merely as reminders of historical events and personages. The particular combination of scenes reinforces the essential Christian message of sin and redemption and culminates in a statement about the importance of prayer as route to salvation. As a sophisticated negotiation of Protestant image theory, this wooden fixture reflects a deep understanding and appreciation of the benefits of religious iconography in communicating and reinforcing faith.

Conclusion: From Rejection to Reconciliation

Our combined evidence reinforces the increasingly clear reality that Protestant reform in England did not lead to a wholesale rejection of religious imagery, in commentary or in practice. In addition, we have uncovered a carefully negotiated stance on what constituted acceptable and unacceptable images. The ways in which Protestant commentators moderated the proscriptions of the second commandment amounts to a complex body of theory, but our table elucidates how the various exceptions and qualifications could be weighed and balanced to inform thinking and behavior.

The two case studies, dating from the first three decades of the seventeenth century, add further material proof to an already extensive body of evidence to establish that religious imagery was made and viewed by conforming and godly Protestants long after iconophobia had allegedly taken hold. But the purpose of discussing them in detail here is to show how applying the various criteria expressed through the chart allows clearer understanding of how these artworks could be judged as not just acceptable but positively beneficial, within the guidance issued at the time. We can see that, in terms of medium, both artworks are part of a scheme of imagery and therefore a process of a story. Both depict histories from the Bible corresponding with specific passages of scripture and thereby conform to the requirement of scriptural fidelity. Nevertheless, these two examples do push the boundaries of acknowledged proscriptions. As we have shown, most commentators considered that all religious imagery in churches should be avoided, while images of holy characters even in a domestic setting risked contravening the similitude part of the second commandment. In both cases, the potential for idolatry was enhanced, because of location on the one hand and subject matter on the other.

Our diagrammatic chart (figure 1) makes clear how these factors were mitigated by other considerations. Both artworks were given integrity by other contextual parts of the model less often commented upon directly, by contemporaries or within the historiography. Firstly, the credentials of the patron seem paramount in legitimizing such works. A clear commitment to Protestantism demonstrated by a godly householder and a conforming parish community allowed such commissions to be understood in the context of edification and demonstration of religious ardor. Secondly, it is clear that the communal, social context of the settings provided the justification of civil use, for ornament and remembrance, even in a parish church (and in line with the guidance offered by the Elizabethan authorities). Both spaces demanded appropriate ornament in order to demonstrate the nature and status of the place, reflecting the expectation that individuals should adorn their environments to appear comely and seemly—that is, fitting to their status, identity, and piety. Crucially, both locations were public, social spaces for a community where artworks were viewed collectively and where reception could be monitored, ensuring that these images served only as remembrances, reinforcing lessons taught by learned minsters and patriarchs.

While the relationship between Protestantism and the image in early modern England could be fraught, it was far from inherently hostile. Recent historiography has battled hard against the conceptual stranglehold established by the paradigms of iconoclasm and iconophobia, but an incremental amassing of exceptions to this model—of art forms that evaded destruction and repudiation—has not offered a sufficiently compelling counternarrative to quash persistent assumptions within a wider interdisciplinary scholarship. Our new model charts how second- and third-generation Protestants negotiated, and embraced, the power of visual art as a tool of edification, a badge of identity, and a declaration of faith.