Duelling,” cautioned the Sheffield Independent, “would appear to be in the ascendant once more.”Footnote 1 This was an unexpected declaration for an English newspaper to make in 1861. Everybody knew that no duel had been fought in England for almost a decade.Footnote 2 But the national press soon echoed, and amplified, the Independent’s warning. The Morning Chronicle, a longtime liberal foe of dueling, issued a “strong protest against … an attempt to revive duelling.”Footnote 3 “Duelling again brings all men to a level!” exclaimed the Daily Telegraph, continuing, with a touch of juvenile gaiety, “a dead level in some cases.”Footnote 4 An indignant Punch urged Lord Palmerston's government to levy punishments of heavy fines and hard labor upon men who issued challenges, lest “the best and wisest fellow” find himself “at the mercy of any reckless fool, blackguard, and bully.”Footnote 5 This sudden clamor by the popular press for greater protection against duelists in the early 1860s was very much at odds with their confident assertions during the previous two decades that duelists no longer existed. “The race of duelists [was] extinct” (1844); “witch-burning and dueling” were equally outmoded, not to say medieval, practices (1851); and, with the advantage of historical hindsight, Victorian commentators could impartially observe “reasons for its decline” (1852).Footnote 6 Less than a year before their request for greater deterrents, Punch complacently declared that dueling was “detested as a vulgar vice.”Footnote 7 If dueling had indeed returned to Britain, did it follow that the elite masculine values that had so long sustained the practice were likewise reanimated?

Two high-profile incidents undermined the popular belief that a new pacific masculinity had replaced an older martial ideal in Victorian Britain. In February 1862, Lord Palmerston intercepted a challenge intended for Sir Robert Peel, son of the famous statesman, by an infuriated young Irish member whom Peel had insulted during a House of Commons debate.Footnote 8 At the same time that this parliamentary challenge was issued, British newspapers contained detailed daily accounts of the court-martial of a Captain Robertson, an army officer whose “colonel had tried to bully him out of the regiment for not having fought a duel.”Footnote 9 Attempts by some members of the popular press to dismiss the Irish MP and the army colonel as laughable examples of outmoded manhood quickly collapsed. Newspapers debated the role of dueling in regulating relationships between men in the gentlemanly class. The continued cultural relevance of the duel in the second half of the nineteenth century runs counter to established social histories of gender and class in modern Britain that point to the eradication of dueling as evidence of two interconnected, long-term trends: the rise of the middle-class gentleman and the decrease in interpersonal violence.

The anti-dueling campaign that culminated in the 1840s was the last in a long lineage of efforts to check the power of the aristocracy, yet the campaign's effect upon aristocratic masculine norms is oversimplified and underexamined in the scholarship.Footnote 10 Derived from the chivalric medieval practice of trial by combat, the highly ritualized violence of the duel regulated elite society in early modern England.Footnote 11 The autonomous and aristocratic code duello was resented by sovereign powers in the modern era as a threat to centralized law. By the eighteenth century, it was the subject of growing resentment from the largely law-abiding general populace.Footnote 12 Social historians, often informed by the Marxist tradition, hail the rejection of a separate law for the rich as a key political platform of the middle-class associational politics that finally overturned aristocratic social dominance by the mid-nineteenth century.Footnote 13 For the field of masculinity studies, the evident cessation of dueling around mid-century was, as John Tosh argues, part of a revolution where “an externally validated honor” was replaced by “the internal spring of ‘character’” and physical self-restraint.Footnote 14 Yet the power of the duel to facilitate male social equality––a role acknowledged by some of the same scholarship that hails the efficacy of middle-class pressure––echoes the nineteenth-century claim that the British aristocracy abandoned dueling to “ridicule and shopboys” rather than allowing the ritual to become a means of social mobility.Footnote 15 The diverse pressures placed upon duelists call into question the notion of an anti-dueling consensus; adherents of an aristocratic masculine code worked in concert with campaigners promoting middle-class values.

Despite the practice's distinctive character, the cessation of dueling is cited by scholars of violence and crime as part of a broader trend of decreasing male-on-male violence in Britain's cities.Footnote 16 As a recent review of the literature on crime and masculinity summarizes, “duels, tavern fistfights, and the public chastisement of servants and wives––became less acceptable as middle-class ideals of rational, law-abiding manhood replaced older concepts of honor, discipline, and proved physical prowess.”Footnote 17 Robert Shoemaker cites duelists’ relocation from urban spaces to commons and heaths in Georgian England as proof that “violence was increasingly unacceptable, and male honor came to depend far less on public displays of bravery and courage.”Footnote 18 Yet, because British duelists by the late eighteenth century heavily favored pistols over swords, duels required open and secluded spaces, for practical as well as legal reasons.Footnote 19 As an elite and extra-urban practice, the statistical decline of dueling coincides, rather than correlates, with reductions in working-class metropolitan male violence. We need to consider the everyday stresses placed upon duelists, particularly changes in nineteenth-century travel and leisure, before we attribute their “extinction” to the triumph of middle-class masculinity.

The 1860s debate over the practice of dueling and the fate of the duelists reveal that there were multiple competing models of gentlemanly masculinity in the mid-nineteenth century. The case of Sir Robert Peel and the parliamentary challenge highlighted public approval for martial as well as pacific masculine virtues. Increased European competition and imperial commitments encouraged an acceptance of those martial masculine models, particularly Celtic and military masculinities, that had been conveniently marginalized in the post-Napoleonic decades. The court-martial of Captain Robertson reflected the often conflicting pressures of professional and domestic models of manhood. The resource of the courts, once held up as the solution to the illegal dispute resolution offered by the duel, began to be viewed as a forum that could destroy men's reputations in a new media era. These popular discussions collectively support a burgeoning scholarly argument that the theory of hegemonic masculinity, prominently formulated by R. W. Connell, has serious limitations for understanding masculinity in Victorian Britain.Footnote 20 Rather than cementing middle-class restraint as the masculine ideal to which aristocratic and working-class men were slowly but inexorably forced to conform, the 1860s debate shows that the decline of dueling occurred in an era when competing masculine ideals overlapped class boundaries. The most important social delineation was the contested category of Victorian gentleman. An immediate need to assert and maintain social status in the face of defamation meant constant questioning: Who was a gentleman? What was honor? And how could a man best defend his claim to either?

The Pacific Englishman

The continued cultural relevance of dueling in Victorian Britain provides important insight into the fabrication of a hegemonic masculinity that strained rather than strengthened a clear understanding of gentlemanly identity. The perennially confusing prerequisites for being a gentleman in modern Britain—a conflicting mixture of birth, wealth, and virtue that has been well documented by historians of class—seemed at last to cohere around middle-class pacific gentlemanliness in the post-Napoleonic decades in a rejection of “aristocratic vice.”Footnote 21 However, the appearance of a popular consensus was achieved by blaming “anachronistic” behaviors like dueling as much upon unenlightened outsiders as upon the aristocracy. Britain's colonies in particular provided a convenient mirror onto which primarily English commentators could reflect, and deflect, present uncertainties about gentlemanly behavior. The author of an 1841 tract on dueling was typical of the period in insisting that, while duelists were “rare” in England, “in Ireland … and in our own colonies, the breed still flourishes––at once the terror and the disgrace of civilized society.”Footnote 22 Yet colonial societies were not mirrors of a past Britain. Research on masculinity in nineteenth-century Australia, Canada, British India, and Ireland has consistently documented that white-settler and overseas military communities experienced considerable social and legislative pressures to cease dueling in the first few decades of the nineteenth century, followed by an intense, mid-century uncertainty over the definition of gentlemanliness.Footnote 23 Depictions of dueling as an expression of an atavistic Celtic masculinity were particularly egregious untruths as affairs of honor had been confined to an Anglo-Irish Protestant elite until the nineteenth century.Footnote 24 Yet the idea that Irishmen and men in the colonies lagged behind—or even acted as a drag upon—modern, middle-class masculinity in Britain has persisted in scholarship on the duel.Footnote 25 It is important to examine the stereotype of the atavistic Celtic duelist because he formed an essential contrast to an equally fictitious character: the always physically restrained and law-abiding modern Englishman.

At first glance, the challenge issued following a House of Commons debate in 1862 supports the thesis that modern gentlemen eschewed violence and that duelists were outsiders. Sir Robert Peel, having succeeded to both his father's Staffordshire seat and the office of chief secretary of Ireland, was challenged to a duel by Daniel O'Donaghue, MP for Tipperary. Peel, who had already alienated Irish Roman Catholic MPs from the Palmerston faction, was speaking on 21 February 1862 to again deny the existence of famine in Ireland. To support his contention that Ireland had “yielded to the good influences of the age in which we live” and was prospering commercially, Peel pointed to the reception of an American delegation in Dublin. Although “a few manikin traitors sought to imitate the cabbage-garden heroes of 1848,” Peel declared that “no respectable man attended the political meeting.”Footnote 26 In fact, O'Donaghue had attended the meeting at the Rotunda in Dublin. Several members cheered Peel's comments and “cast derisive glances” at O'Donaghue, who then left the House with “dark hints of what it might be necessary to do for the vindication of his honor.”Footnote 27 O'Donaghue insisted that being publicly labeled a traitor was a personal rather than a political insult. His parliamentary colleague, a Major Gavin, attempted to present Peel with a challenge that night. Gavin was not as quick as Palmerston, who had already instructed Peel to refer O'Donaghue's emissary to him. This move forced O'Donaghue's second to receive a lecture from the prime minister about the rules of debate in the House rather than to deliver his challenge.Footnote 28 The police presence that Palmerston requested at Westminster the following day was a further illustration that gentlemanly honor was now compatible with modern law and order.

To interpret the response to O'Donaghue's challenge as evidence of a consensus against gentlemanly violence ignores that the incident was a well-crafted piece of political showmanship. Palmerston's handling of the 1862 challenge in the House of Commons is evidence of his opportunistic use of the emotive language of “Englishness” when, as David Brown argues, it suited his policies.Footnote 29 Behind the scenes, Palmerston was far less calm. His first, and necessary, step had been to warn Peel against accepting O'Donaghue's challenge. Although the national press assumed an air of studied disinterest in the case, it was general knowledge that Peel had acted as a second in an 1851 duel at the West London suburban estate of Osterley Park.Footnote 30 Palmerston then woke up the solicitor general in the middle of the night to learn whether giving or receiving a challenge constituted a parliamentary breach of privilege, preparing for his cool dismissal of the case the following day.Footnote 31 Ignoring the many famous nineteenth-century parliamentary encounters, including Sir Robert Peel the elder's famous 1815 arrest on route to fight a duel with Daniel O'Connell, Palmerston framed the mooted duel as an attack on the hallowed parliamentary principle of “freedom of expression.”Footnote 32 The legislative tradition that was actually maintained was far more pragmatic and cynical. Palmerston's Liberals were reusing the Peelite tradition and its brand of Englishness to neutralize descendants of Daniel O'Connor—O'Donaghue was O'Connor's grandnephew—and their evolving campaign for Irish rights. To read this incident as a gentlemanly consensus against armed combat is to accept Palmerston's public posturing as the whole story.

Framing his party's response to a literal attack around pacific, rational masculinity should have assisted Palmerston in accessing a deep reserve of popular support against dueling, but the press response was divided. The anti–Irish rights press eagerly elaborated upon Palmerston's inference that O'Donaghue and his friend were fire-eating Hibernians, what David Anderson has termed the “hysterical Celts” of popular imagination, determined to subvert an open and free democratic debate.Footnote 33 English legislators were, by contrast, models of restrained, mid-century masculinity. The Times painted a verbal portrait of “The O'Donaghue” striding down Parliament Street as one of his sixteenth-century ancestors might have done “with a score or two of half-naked savages at his heels, carrying axes and crossbows.”Footnote 34 A Punch cartoon of O'Donaghue as a hypermasculine, mace-wielding Celtic barbarian, literally throwing down his gauntlet (figure 1), closely imitated the Times’ description. In the same image, the restraining Palmerston and the indignant Peel each wear that most indispensable article of Victorian gentlemanly status: a top hat.Footnote 35 Yet, in contrast to these biting satirical portraits of the Tipperary MP, several London weekly reviews excused O'Donaghue's challenge by expressing their poor opinion of Peel. The popular Illustrated Times condemned the “hard phrase” used by the “rash and impetuous” Peel.Footnote 36 At the other end of the publication market, the select London Review contrasted the “young mild-mannered Irishman” O'Donaghue favorably with the “impetuous Irish Secretary” in their highly unflattering feature on Peel.Footnote 37 The amusement, too, was not all at O'Donaghue's expense. A joke circulating in London's political clubs was that “whatever becomes of the Ministry, Sir Robert Peel would not ‘go out.’”Footnote 38

Figure 1 —“The O'Mannikin,” Punch, 8 March 1862, 94.

Palmerston's political use of personal combat as the dividing line between modern Englishmen and backward Irishmen was further blunted by the imperial revival of chivalric masculinity and the rehabilitation of “barbarians.” As Bradley Deane concludes, the nineteenth-century notion of “barbarism” was not simply a reversion but “an ideology with its own history, actively encouraged and sustained by a set of carefully elaborated fantasies.”Footnote 39 While the perennial charges that dueling was illegal and immoral had only a fitful impact on the practice, the accusation begun in the Georgian era that dueling was “barbaric” was a damning indictment to the century's many clean-shaven gentlemen.Footnote 40 Neo-medievalism blunted the pejorative power of premodern masculinities, and as Mark Girouard first conclusively illustrated, the character of the modern knight was cultivated by the bloody imperial struggle.Footnote 41 Historians of empire have now firmly established that soldiers and explorers, populations in which Celtic masculinities were well represented, were popularly imagined as knights-errant.Footnote 42 Highland soldiers, a less politically problematic, if equally fabricated, image of unreconstructed manhood in the nineteenth century, became synonymous in popular culture with “chivalric masculinity.”Footnote 43 Popular imperialists began to overtly identify themselves with the “barbaric” masculinity of the men they encountered.Footnote 44 These interlinking trends were poised to render the Celtic barbarian depicted by Punch a more ambiguous figure in the second half of the nineteenth century than Palmerston's supporters intended. Indeed, the expanding imperial project required that idealized English masculinity co-opt some of the allegedly outdated martial masculinities that had previously been employed to exaggerate a consensus against interpersonal violence in England.

The Martial Briton

The rejection of dueling demarcated “civilized” Britain from her foreign rivals in the immediate post-Napoleonic period. But a renewed British desire to appear ready for European warfare resurrected the popularity of the martial model of manliness. The new, radical-leaning, middle-class monthly magazine Temple Bar proclaimed in 1861 that the recent heroics of the Crimean War and the Indian Uprising had “grafted a new flower of chivalry upon the old stock.”Footnote 45 As the Daily News acknowledged, there was an intimate link “between the settlement of private and of national quarrels by violence instead of by reason and arbitration.”Footnote 46 An increase in dueling at moments of national birth and rebirth further complicated British insistence that dueling was an outmoded custom. Scholars of European masculinity highlight the significance of the duel as “an aristocratic concept of male honor [that made] its own contribution to the construction of modern masculinity.”Footnote 47 Indeed, dueling was an active agent in the creation of the masculine Republican ideals of the French Third Republic and in “the arrival of a liberal, constitutional regime” in the Italian peninsula.Footnote 48 In the emerging republics of both North and South America, dueling provided a focal point for elite debates on how to fashion a new nation.Footnote 49 The 1860s was a particularly concentrated period of national reformation, a fact that reinvigorated dueling in the Western world while simultaneously spiking international interest in the encounters. The British press closely followed foreign duels in the early 1860s. France, Prussia, and Italy were each in turn said to be suffering from a “duelling mania”; the United States meanwhile was in the grips of a “duelling epidemic.”Footnote 50 Britain was less internationally exceptional than popularly portrayed in its rejection of dueling, and we must therefore question the inference that British masculinity, like the nation's economy, modernized in advance of other nations.Footnote 51 Although British commentators seized upon the copious quantity of foreign duels to illustrate the comparatively uncivilized character of other nations, the popular debate of 1862 revealed that the British gentlemanly classes were not immune to the appeal of personal combat during this dynamic decade.

The revival of the dueling debate after the collapse of the peace movement in Britain demonstrates the perceived link between personal and militarized violence. During the liberal euphoria in the late 1840s and early 1850s, the near eradication of dueling in Britain was seen as a harbinger of permanent peace. As an 1852 public letter in defense of a peace society declared, “The reprobation passed on a brace of pistols will be alike effectual upon parks of artillery, and broadsides of ships of the line.”Footnote 52 The delegates at the International Peace Congress (1848–1853) passed a resolution against dueling in 1850 and imagined that the expurgation in Britain of “war between individuals” was a precursor of greater peace.Footnote 53 The Congress even created a space in which gentlemen of all European nationalities could publically confess and repent of dueling.Footnote 54 The ambitions of the Congress for radical reform were not those of the majority of Britons, but they echoed mainstream thought in their belief that the abolition of dueling in Britain was a fixed historical event rather than a contingent conclusion.Footnote 55 Instead, the evaporation of hopes for peace in Europe endangered the imagined consensus against dueling. An article in the Army and Navy Review that filtered into the mainstream press insisted that it was hypocritical for the British to despise dueling yet still talk of “the moral benefits accruing from war.”Footnote 56 The resurgent popularity of military solutions for national problems imperiled domestic accord on what forms of defense a gentleman might acceptably use on his own behalf.

Although Britain remained removed from active European warfare in the post–Crimean War period, Britons still summoned imaginary contests with continental rivals through manufactured scenarios like the Volunteers and more organic developments such as mass travel. As travel became a form of popular entertainment in Victorian Britain, more middle-class men were exposed to the question of whether or not to fight if challenged abroad. Indeed, recent research showing how diplomatic duels extended the lifespan of the practice suggests that international exchange could have a deleterious as well as salutary effect upon duelists.Footnote 57 There was little censure, and even some praise, when Lord Howden acted as a second in an 1853 duel between his American and French counterparts while serving as the British ambassador in Madrid.Footnote 58 As the Grand Tour, with its pressures upon privileged “young continental tourists” to fight foreign antagonists, gave way to package tourism, British gentlemen had to decide whether to abide by new British social dictates or prevailing European customs.Footnote 59 This conundrum was not, by the 1860s, a personal choice but a matter of national interest to the conservative press. Noting the tourist appeal of the gas-jet illuminations of the Mabille Balls in Paris, the Standard insisted that young British men should fight a duel if challenged by a Frenchman.Footnote 60 As the more moderate Glasgow Herald explained in 1865, demurral from duels might be construed as “the basest poltroonery” by foreigners and “expose us to undue liberties.”Footnote 61 A British gentleman defended the reputation of his nation when he protected his personal honor abroad.

While international events were credited with creating a “military feeling” in Britain, the increased appeal of martial display in the 1860s was also fed by a desire for manly leisure pursuits among the gentlemanly classes. The high-profile wars of the 1850s were immediately followed by two largely spurious French invasion scares in 1858–59 and 1862. In a period of extensive global cooperation with France, including in Peking (1860) and in Mexico (1861), the resulting Volunteers movement was an emotional rather than a strategic response fed by what Ian Beckett characterizes as an “increasingly hysterical press campaign.”Footnote 62 The perennial excuse of national martial preparedness for aristocratic recreations, such as hunting, now justified sport and leisure for an expanded and urbanized gentlemanly population.Footnote 63 Proponents of “muscular manhood” and sports-focused education in boys’ public schools were, unsurprisingly, supporters of the Volunteers.Footnote 64 Joining the Volunteers allowed British gentlemen an opportunity for extra-urban recreation via highly visible displays of martial prowess. The Volunteers promoted a knightly ideal, and “fair English maidens” were publicly urged in 1862 not to accept suitors until they had demonstrated their ability to put “a bullet into a target at 900 yards.”Footnote 65 As figure 2 shows, the men in uniforms with peaked forage caps lounging in picnic chairs or else mixing on equal terms with spectators in top hats mark the heavily publicized shooting competition as a genteel event. The contestants practice their marksmanship on Wimbledon Common, site of some of the nineteenth century's most famous duels, including the Canning–Castlereagh political contest (1809), the Earl of Cardigan's exchange with an army subordinate (1840), and the future emperor Napoleon III's contest with his cousin (1840).Footnote 66 The European implications of such displays of marksmanship were clear. As the Glasgow Herald boasted, the “spontaneous” raising of a volunteer army “should teach the world of schemers and duellists that Britain has still the heart and the hand to strike when the proper time comes.”Footnote 67 This increased public interest in martial vigor created a new vogue for the sports and leisure that were once associated with aristocratic martial masculinity.

Figure 2 —“National Rifle Association Meeting, Wimbledon Common, Shooting Queen's Prize,” Illustrated London News, 20 July 1861, 54.

The twin strategies of depicting duelists as outsiders or as relics of Britain's past were turned on their heads in the 1860s. European competition prompted commentators to rehabilitate the violence of the past and those present-day expressions of martial masculinity. The conservative Standard, a paper whose revitalization in the 1860s was aided by its in-depth coverage of the American Civil War and the Prussian-Austrian War, was particularly conspicuous in championing “respectable” military men who still believed in the “moral efficacy of duelling.”Footnote 68 When a retired colonel running for parliament challenged his opponent to a duel in 1865, the Standard noted that he was “galled by a sense of wrong, publicly and disgracefully insulted, and governed by an old tradition of all European armies.”Footnote 69 British commentators became preoccupied with how their nation appeared to outsiders and resurrected their own violent past as proof of national vigor. The Morning Post, another conservative daily, concluded an 1869 article on dueling in the newly unified Italy with the boast that present-day Italian men could not compare with the fighting editors from the paper's own hot youth.Footnote 70 References to past dueling prowess served a nuanced purpose for the more liberal press outlets: they declared Britain more advanced than its neighbors and yet still as masculine as they were. The Graphic, a pro-reform weekly picture paper, insisted in 1870 that, while other nations might unfairly point to “a growth of effeminacy,” Britons’ dislike of dueling was due to their extensive experience of the custom.Footnote 71 With no clear division between domestic and foreign, past and present, the increasingly mobile Victorian gentleman had to negotiate between the pacific ideals of the early nineteenth century and the martial ambitions of the present day.

The mid-Victorian debate on dueling, with its links to popular politics and culture, allows us to create a more complex view of British masculine identities. It connects the Volunteers movement of the late 1850s and 1860s with the “knightly” ideal of crusading soldiers that allowed for a hardening attitude toward British violence in the empire. In both cases, the need to make gentlemanly violence “honorable” resurrected older ideals of elite male behavior; this rehabilitation of the medieval and even pre-medieval past defanged critiques of dueling as “barbaric.” Even vocal denouncements of dueling in this period must be read as expressions of foreign and colonial agendas. The Times, so damming in its portrayal of O'Donaghue after his challenge against an English legislator, took little interest when his 1869 challenge to a fellow Irish-Catholic politician was accepted.Footnote 72 The precarious balance between the conflicting yet interdependent pacific and martial models of masculinity was controlled by national trends and international events. In their day-to-day lives, men claiming membership in the gentlemanly classes faced the challenge of balancing the competing obligations of their professional and personal identities. While the interior workings of the Peel-O'Donaghue case were largely shielded from public view by Palmerston and his supporters, the concurrent case of Captain Robertson gave the British reading public an inside perspective on a Victorian challenge.

The Professional Gentleman

While the parliamentary fracas played out in Westminster, a Crimean War veteran stood trial for “conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman” after failing to properly defend his reputation. Officers were required by the military code to defend their reputations, and this occupational demand contributed in no small measure to the Army and Navy's reputation as inveterate duelists who were slow to concede that “the concept of gentlemanly conduct [had] altered” in favor of restrained Christian virtue.Footnote 73 The difficulties that officers experienced in satisfying this requirement in the mid-nineteenth century rendered the traditional military charge suddenly resonant with civilian gentlemen struggling to defend their own reputations using the civil courts and the press. In her work on the Scottish Enlightenment, Rosalind Carr concludes that, however persuasive the arguments against the “barbarous social custom,” they never translated into a “consensus” against dueling simply because they could not “negate the importance of public reputation.”Footnote 74 Like military men with their no longer insular courts-martial, civilian professionals were by the mid-century largely reliant upon exhaustively chronicled legal processes in order to repair damage to their public reputations. Aristocratic men had once defended the practice of dueling by claiming that their honor was the same as their lives. An enlarged gentlemanly population in the mid-nineteenth century equated their reputations with their livelihoods.

The reason for Arthur Robertson's twenty-eight-day court-martial in February and March 1862 was his failure to issue a challenge after a dispute at the Army and Navy Club. On the night of the quarrel, Robertson encountered a man that he had fallen out with over the money that came with Robertson's marriage. The marriage trustee's insult, issued in a loud voice in the Club's entrance hall, was calculated to strip Robertson of his gentlemanly status: “This is Captain Robertson of the 4th Dragoon Guards––he is a blackguard, and I will horsewhip him before his regiment!”Footnote 75 While a challenge to duel asserted “an equality of genteel rank,” a threatened horsewhipping produced the opposite effect.Footnote 76 Robertson attempted to ignore this public attack, but as an army officer he could ill afford to do so. Professionally, a military officer's individual honor was the same as his regiment's honor and must be defended.Footnote 77 Once he realized his error, Robertson tried in vain to privately arrange a duel with his insulter. His commanding officer insisted that Robertson publicly goad his antagonist into a duel, an act that the commander claimed “was a strong measure, but there was nothing else to be done.”Footnote 78 Although belatedly willing to hazard his life in a private encounter, Robertson refused to risk a libel action by making a published attack lest the whole affair “obtain a disagreeable notoriety” in the courtroom.Footnote 79 His insulter continued to defame Robertson while out riding in Hyde Park and hunting in the Home Counties, so the officers of the Fourth Dragoon Guards, first stationed in Birmingham and then in Dublin, sought to hound him out of the regiment before their collective honor was further damaged. Robertson later claimed that, in order to “escape the everlasting persecution” by his brother officers, “he could almost have drowned himself.”Footnote 80 It was Robertson's protest against these bullying tactics that landed him in the last place he wished to be: in court and on the front page of national newspapers.

While there was a touch of dark comedy in the predicament of a man on trial for failing to commit an illegal act, the impasse of Robertson and the Fourth Dragoon Guards was taken seriously by the major news outlets that sent correspondents to Dublin to cover the court-martial. Despite the inevitable censure from traditional liberal dailies of military officers who were “seeking to revive the worst practices of dark and savage days,”Footnote 81 coverage of the case quickly developed into a genuine discussion of “the abstract principle of duelling which is on trial.”Footnote 82 The new penny press saw the significance of the court-martial for their readers, with the Telegraph reflecting that a gentleman in “ordinary civilian life” struggled to respond to a gross insult such as the one Robertson had received in a way “which will accord at once with the laws of the country, the views of society, and his own sense of dignity and self-respect.”Footnote 83 The Morning Post thought the Robertson case was a “very pretty Gordian knot to unravel, social and military,” and declared that the abolition of dueling “should have been postponed until it could have been replaced.”Footnote 84 Encouraged by this civilian sympathy, the previously cautious editor of the Naval and Military Gazette admitted that he was “better contented under the code of honor.”Footnote 85 Even vehemently anti-dueling publications were forced to concede that the practice's “abolition” had not necessarily improved gentlemen's social intercourse. The Post’s soon-to-be-discontinued rival, the Morning Chronicle, sniffed that it was “far better that men's manners should be rough” than that they should endorse “an institution which insults the laws of God and violates the laws of man.”Footnote 86 The Robertson court-martial focused civilian dissatisfaction on legal arbitration that invited potentially embarrassing exposure in the press and increased the appeal of more exclusive methods of arbitrating professional disputes.

Dueling was a fascinating legal problem for both civilian and military communities, but these difficulties were reflected in, rather than solved by, the laws which governed appropriate responses to defamation of character. When Sir Robert Peel, the prime minister, in 1844 refused to debate proposed legislation against dueling, he noted that “public sympathy” was a flexible quality and predicted that, if duelists “were again to arise,” the courtrooms in which they might be tried were “very much under the influence of public opinion.”Footnote 87 Accordingly, although support for new laws against dueling in the civil and military code peaked in 1844, very little was achieved legislatively. The lone direct legislative action against duelists, the 98th Article of War, contradicted existing military law, and the judge advocate general was forced during the Robertson court-martial to concede that a new article was required “to regulate the conduct of officers whose character may be impugned.”Footnote 88 Legislation designed to facilitate personal prosecution, including the Offenses against the Person Act of 1837 and the Libel Act of 1843, were thought to promote non-violent dispute resolution.Footnote 89 However, Margot Backus traces the birth of New Journalism to this loosening of Britain's strict libel laws, and we can see from the debate over the protection of gentlemanly reputation how legal changes “destabilized an earlier, more absolute division of public and private morality.”Footnote 90 The increasing scope of court reporting that coincided with the growth of the press in the 1850s rendered the courts a far more problematic ally. Although the performance of individual officers during the Robertson court-martial were sometimes satirized by the press, the new middle-class weekly periodicals of the 1860s used their blend of opinion and story-telling to portray army officers as the victims of a cumbersome and punitive legal system.Footnote 91 Witnessing the events in Dublin in 1862, the Cornhill Magazine lamented that “accusations enough are exchanged in court and in the newspapers to make the regiment a hell for months or years to come.Footnote 92 Indeed, the public sympathy for Captain Robertson and his subsequent acquittal—thus saving him from the devastating loss not only of his occupation but the purchase price of his captaincy—demonstrates the flexible quality of that public opinion against dueling in the 1840s that has frequently been converted into a “consensus” in favor of pacific middle-class masculinity.

If the ability of the courts to enforce a dictate against violent dispute resolution was dependent upon the mutable quality of public opinion, the popular press both curated and undermined the public opinion against dueling. As Sarah Cole has recently demonstrated, an overemphasis upon the anti-aristocratic nature of middle-class masculinity in the post-Napoleonic period had a destabilizing effect; “this narrative of middle-class triumph soon generated its counternarratives of middle-class failure.”Footnote 93 The press, popularly believed to be the best gauge of public opinion by the mid-nineteenth century, certainly held a high opinion of its role in promoting anti-dueling sentiment.Footnote 94 The editor of Lloyd's Weekly Newspaper boasted in 1852 of how the press succeeded in growing “opinion” against dueling from a stricken “seed” into “a tree of strongest root and robust dimensions.”Footnote 95 However, in practice, the popular press focused on sensational episodes to attract readers’ attention, and coverage of dueling veered wildly in tone and focus as a consequence.Footnote 96 A nineteenth-century tract mocked this press response, noting that, in the case of serious injury, a duel was “denounced in the lurid leading columns,” whereas uninjured parties were “treated as fools, and the whole affair is covered with ridicule!”Footnote 97 Cases that did not conform to farce or tragedy, such as Sir Robert Peel the younger's 1851 duel, were largely ignored by the press. The reactive nature of the anti-dueling campaign made it dependent upon current events and vulnerable to the “counternarrative” described by Cole. It was little to be wondered at when Punch declared in 1862 that “the formation of public opinion in favor of duelling ought to be checked at once.”Footnote 98 Although essential in promoting anti-dueling sentiment in the first half of the nineteenth century, the press proved an unreliable custodian of pacific male virtue and an uneasy ally of professional men under pressure to publically defend their reputations in court and in “the court of public opinion.”

The press-framed debate over dueling, with its self-interested promotion of open courtrooms and public discourse, hindered the implementation of non-violent, extra-legal methods of gentlemanly arbitration. Anti-dueling campaigners declared that dueling was diametrically opposed to legal, nonviolent methods of resolving disputes, yet gentlemen in the mid-Victorian period continued to experience a continuum between legal and extra-legal methods when they sought to defend their reputations. As scholars of extra-European masculinity have established, “the courts and the press” were used to “attack and defend reputations” in ways that mimicked the “rituals” of the duel.Footnote 99 “Courts of Honor,” in their various civil and military incarnations, had stood between dueling and the regular judiciary since the early modern period.Footnote 100 Several Victorian schemes for a “Court of Honor” were proposed in 1844.Footnote 101 Prince Albert favored establishing an honor court along modern Prussian lines.Footnote 102 Even the Association for the Discouragement of Duelling finally conceded that there needed to be an alternative way of “meeting the want in society … over which neither the courts of law [n]or equity can exercise an effectual control.”Footnote 103 When no such scheme came to fruition in the United Kingdom, extra-legal dispute resolution was limited to threats of illegal violence.

The failure to find a true replacement for dueling resulted in a climate of uncertainty that, commentators worried, unscrupulous men might exploit. British politics, assisted by the presence of retired military officers, was the professional sphere most associated with nineteenth-century dueling after the military itself. A contest between two candidates during the 1852 general election was the last-documented completed duel between two Englishmen in England.Footnote 104 Nor did political aspirants altogether abandon the political utility of dueling thereafter. A retired colonel running for parliament in 1865 was taunted by his civilian opponent “that fighting had been the colonel's trade, but it was not now.”Footnote 105 The colonel's supporters saw calculated malice in such a statement; the opponent knew that the colonel would respond to the taunt with a challenge, and he obligingly did. This scandal echoes the popular feeling that Peel intentionally insulted O'Donaghue with a hope of provoking a challenge.Footnote 106 In the same issue of the Illustrated Times that featured a cover image of the Robertson court-martial, the parliamentary reporter who observed the altercation between O'Donaghue and Peel bristled that the Irish Secretary knew that “no Irish gentleman would quietly swallow such an insult.” An 1869 episode in a London courtroom illustrates how such “baiting” strategies brought dueling into play with legal, as well as illegal, methods of resolving disputes. Having come into conflict over the content of some articles, a newspaperman took a peer to court for “using language with a view of provoking a duel.” A scuffle broke out after the hearing at Marlborough Street in which “chairs were broken, hats smashed, and one of the persons met with very rough treatment.”Footnote 107 Talk of dueling among professional gentlemen was due to frustration with the present-day constraints of legal dispute resolution—and the perceived liberties taken by their fellow professionals as a result.

A central conundrum exposed by the two 1862 dueling case studies was that gentlemen were still required to take action upon being insulted and yet were uncertain as to what that action should be. As a consequence, the insulter and not the challenger became the more reviled and feared. A regular correspondent of the Naval and Military Gazette observed that “the general feeling elicited” by both the Irish member and the Dublin court-martial “as expressed in many publications” revealed that the public condemned the “savage insulter” more than “the challenger who takes up the defense of his own right.”Footnote 108 It was often a desire for greater civility between gentlemen that prompted the espousal of pro-dueling sentiment. The Standard thought that many an “outrage” would simply not have occurred when “a reply would have come to him from the point of a sword or a pistol's muzzle” and lamented how the legal system was now used to protect “jibing upstarts who can be so courageous in the defense of their own timidity.”Footnote 109 The editor of the NMG thought that “the bully and the slanderer” had “taken advantage of the almost total suspension of that much abused appeal to arms.”Footnote 110 O'Donaghue and Robertson's antagonists represented the “bullies” that any gentleman might encounter in public life. Yet the ability to successfully counter such public disrespect depended not only upon a gentleman's public character but also upon his private circumstances.

The Private Man

The case of Captain Robertson points to the ambivalent role of domesticity and chivalry in the advocacy of pacific masculine ideals. Scholars of Victorian masculinity, most prominently Tosh, cite the increased status of men's domestic identities as a key factor in the creation of a new standard of self-controlled, other-focused middle-class manhood.Footnote 111 Meanwhile, historians of gender and politics have urged scholars to appreciate “how male responses to domesticity remained complex and ambivalent” throughout the modern period.Footnote 112 This is certainly true of violence and domesticity. Ben Griffin has persuasively reasoned that the reframing of domestic violence as a working-class social problem reflected a wide variety of positions on male domestic authority and was inspired in part by a desire to protect elite male privilege.Footnote 113 Popularly expressed fantasies of violence, in literature and in the theatres, enjoyed a similarly ambivalent relationship with the domestic sphere, ranging from chivalric fantasies of defending the home to Sensational representations of the home as the chief source of interpersonal violence. Popular crime panics centering upon garrotters and housebreakers in 1862 focused primarily upon middle-class male victims, echoing Lucy Delap's caution that “historians’ accounts of chivalry gives a false picture of consensus” in the nineteenth century.Footnote 114 In the context of this broader cultural conversation about gentlemanly violence, the revived interest in dueling that coalesced around the case of Captain Robertson is part of a forward-facing historical intervention necessary to counter the narrative of the smooth rise of a pacific masculine ideal.

The family was heavily invoked during the campaign against dueling and during the revived public debate of the practice, highlighting the ambivalent role of domestic identities in the creation of pacific masculinity. Anti-dueling campaigners in the early Victorian period argued to good effect that a gentleman's domestic obligations were more important than his personal honor.Footnote 115 A fatal 1843 duel between two brothers-in-law, the 1844 passage of military legislation to deprive duelists’ widows of their pensions, and even Queen Victoria's own publicly expressed “disapprobation and abhorrence of the practice” the same year, all contrived to put the idea of the family at the center of the dueling debate.Footnote 116 Yet, as the Robertson case shows, apologists for dueling in the 1860s also used the emotive image of the domestic sphere. Robertson's failure to issue a challenge was framed by his brother officers as part of a pattern of failure to publicly uphold his familial obligations. Before his altercation at the Army and Navy Club—with, revealingly, an old friend of his wife's family—Robertson had been warned by a fellow officer to “keep his games to himself,” as gossip had become common that he was frequently seen walking with “an improper female” on Birmingham streets.Footnote 117 An officer who chose to remain on intimate terms with Robertson when the regiment moved to Dublin was told that “being a married man [he] ought to feel [Robertson's] misconduct doubly.”Footnote 118 While some of the antagonism that Robertson experienced might have been due to sympathy for his wife, his fellow officers were clearly angry that Robertson's private conduct would reflect poorly upon their own reputation as a regiment. As long as the domestic sphere, with its female inhabitants, remained a cipher for gentlemanly contests of reputation, it remained a flexible force as regards male-on-male violence.

If we observe the class and gender dynamics of the final distillation of the anti-dueling movement in the 1840s, we see greater coherence between two seemingly polarized positions. The overwhelmingly male and elitist network that ultimately claimed responsibility for the “death of the duel” is suggestive of its socially conservative ambitions. The important role of women's voices, as used by both female and male writers in the eighteenth century to critique dueling as “unmanly,” was supplanted by private, elite male correspondence networks, notably between Jeremy Bentham and the Duke of Wellington.Footnote 119 The Association for the Discouragement of Duelling, formed in early 1842, recruited its male members exclusively through personal invitation and insisted upon “quiet and unostentatious” promotions such as circulars and letters to newspapers.Footnote 120 The Association for the Suppression of Duelling, although providing the alternative of an open subscription society upon which so many popular reform movements were based, nevertheless boasted of its entirely male members’ high status when it formed the following year.Footnote 121 Despite the utility of women as practicing activists as well as symbols of morality, as shown by the previously discussed contemporary Peace Movement, these associations paid little heed to the argument of a successful temperance campaigner who advocated mobilizing female opinion, noting that women's views would carry great weight “with young men of the duel-exposed class.”Footnote 122 The immediate decline and demise of the Association for the Discouragement of Duelling after the high-profile denouncements of the practice in 1844 further suggest that the final triumphant incarnation of the anti-dueling campaign was focused on reforming a symptom of elite male privilege rather than on addressing class- and gender-based disparities.Footnote 123

Fantasy violence in the domestic setting in 1860s popular entertainments provided a cathartic outlet for gentlemen faced with the difficulties of internally policing their peer group while defending the gentlemanly classes’ privileged position as performers of legitimate violence. Like the symbolic as well as physical threat of a horsewhipping, dueling had always contained a fantasy component—it did not need to be fully performed in order to serve its social function—and the increasing impracticality of its full performance allowed dueling to merge more fully still with the world of imagined violence. The masculine predicament of how to defend family honor was explored in fictional form in an Anthony Trollope novel that began to be serialized in the new and very popular middle-class monthly Cornhill Magazine in 1862. Emelyne Godfrey hypothesizes that Trollope, who often fictionalized current events, observed “a yearning fascination among young men towards duelling” in the 1860s and that his work demonstrates “lingering doubts as to the appropriate response to a duel.”Footnote 124 The old squire in Trollope's The Small House at Allington is appalled by the idea of bringing family affairs, specifically the jilting of his niece, under the scrutiny of a courtroom. He wistfully reflects that in the days of dueling “a man was satisfied in feeling that he had done something” and he wishes that “any other punishment had taken its place.”Footnote 125 While the old man's sorrow for his young female relation is genuine, the chief social problem is that a man is publically passing as a gentleman when his private conduct disbars him from full membership. When the young hero of the novel finally shakes off similar indecision as to the acceptability of violent retaliation and publicly assaults the jilter at the railway station, overturning a stand of yellow shilling-novels at the W. H. Smith stall in the process, he succeeds in shaming his opponent by blacking his eye.Footnote 126 He has literally marked the jilter out as a scoundrel in a way that is intelligible to other gentlemen. Although a man might approve of a shaming public assault and disapprove of a challenge to duel, invocations of fantasy violence in popular novels reflected the way in which the domestic sphere might be utilized to justify the use of violence in order to protect a gentlemanly group identity.

Potent as were fantasies of knightly violence in defense of women, the simultaneous rise of the Sensation craze in the early 1860s suggests that fictional gentlemanly violence was also a response to challenges from women. As Griffin's argument about the contemporary campaign against domestic violence makes clear, anti-violence rhetoric in this period must be viewed in light of a need to preserve elite male privilege against challenges along gender as well as class lines.Footnote 127 Sensation was a potent mixture of lower-class melodramatic formulations and middle-class audiences whose presence did not lessen the violence of the spectacles.Footnote 128 “Murder, brutal forms of discipline, duels and brawls,” Rosalind Crone claims of mid-nineteenth-century entertainments, “were presented to audiences in a more extreme manner than they had ever been.”Footnote 129 The spectacular growth of the middle-class magazine market was due in part to Sensation fiction and its altogether more troubling portrayal of violence in the domestic sphere. In Mary Elizabeth Braddon's Aurora Floyd—which was serialized in the Cornhill’s competitor, Temple Bar, at the same time as The Small House at Allington—the heroine uses a horsewhip to chastise a scoundrel. Discovering her in the act, her husband is horrified, insisting to the man whom she has corporally chastised that “it was her duty to let me do [the whipping] for her.”Footnote 130 The husband's own possession of a home arsenal with all the equipment of a sporting gentleman, Marlene Tromp argues, reflects his capacity for violence against his wife as well as his ability to defend her.Footnote 131 The debates about both domestic violence and dueling in the mid-nineteenth century are evidence of a need to defend elite masculinity.

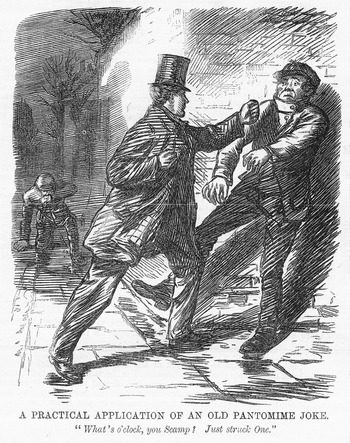

A popular crime panic, surfacing just a few months after the Robertson court-martial, blended real and fantasy gentlemanly violence and suggests how we can place Victorian discussions of dueling into a broader cultural history of gender, class, and violence in modern Britain. The garroting panic that occurred in the summer of 1862 made middle-class Londoners of both sexes frightened of being throttled then robbed in the public streets.Footnote 132 This fear of attack was particularly problematic for men who were expected to have unfettered access to the city's streets. As we see from the Punch cartoon “A practical application of an old pantomime joke” (figure 3), the desire to be able to physically retaliate against these much-publicized attacks took hold of the public imagination. The gentleman in the cartoon, his class designated by his top hat and overcoat, has already “struck one” of his roughly-attired assailants—garrotters worked in pairs—and it is clear from his upright pugilistic stance that he is about to “strike two” in the approved fashion of a gentlemen boxer. Just as the press portrayed duelists as outsiders to mainstream English society, garrotters were commonly believed to be returning Australian convicts who had learned the underhanded tricks on the prison hulks.Footnote 133 By framing debates about English masculinity around an outside threat, the popular panics of 1862 were significant precursors of the public endorsement of extreme violence overseas in the same decade, the vociferous nature of which caught some members of the press off guard.Footnote 134 Just as the dueling debate demonstrated a disinclination to delegate the protection of men's reputations to the courtroom, the garroting panic exposed concerns about deputizing self-protection to the police and popularized the practice for gentlemen to carry concealed “life-preservers,” flexible sticks with leaded weights upon the end, a practice that continued into the next century.Footnote 135 The garroting panic brought the exclusionary masculinity at the heart of the anti-dueling campaign full circle. Once again, the perpetrators of criminal violence were atavistic specters from the nation's past returning to haunt the Britain of the present day. But, as the popular response to the panic indicates, the “Pacific Englishman” was a flexible model of masculinity when it came to violent retaliation.

Figure 3 —“A Practical Application,” Punch, 20 December 1862, 254.

Conclusion

We require a more nuanced model of masculinity if we are going to answer important questions about violence, class, and gender in nineteenth-century Britain. In order to achieve this recalibration, it is essential that we jettison a nineteenth-century historiography that alternately announced interpersonal male violence as an unfashionable vice of the aristocracy and as a working-class weakness. The middle classes certainly encroached upon traditional aristocratic privileges like dueling, but we cannot read these checks as a collective rejection of genteel, masculine violence. The ability to commit and counter interpersonal violence remained an important component of Victorian masculinity in all classes. The social, and to a lesser extent legal, restraints placed upon interpersonal violence influenced the degree to which this ability might be acted upon, but it did not negate the original prerequisite. A gentleman had recourse to the courts and to the newspapers to arbitrate a disagreement, but not because he was afraid to meet the scoundrel in the street. A gentleman could delegate the protection of his person and family to the authorities, yet he must be able to defend himself and his home if attacked. And, of course, a gentleman should not fight a duel—provided he was unafraid to do so.

A clear caution against hegemonic Victorian masculinity, the dueling debate makes a compelling case for a model of gender that accounts for powerful competing trends. Calls for greater official response to crime were perennially mixed with self-reproach for having originally delegated the performance of violence to an authority—and with worries that manliness was deteriorating in consequence. In order to appear militarily competitive, English middle-class restraint had to be tempered with clear potential for violent retribution. This pressure complicated the “backward” status of Celtic and other colonized masculinities and was ultimately resolved with controlled army displays. By returning our gaze to the popular debates of the nineteenth century, we see how martial and pacific values were interrelated ideals rather than opposing forces. We can allow older masculine ideals to coexist with, rather than to cancel out, more modern values. This flexibility enables us to productively consider masculine behaviors that might otherwise be dismissed for being out of step with the “spirit of the age.”

Professionalization and domestication are held to have had a pacifying and controlling effect upon British masculine norms, but the effect of these interlinked trends upon attitudes toward violence was decidedly more mixed. If we wish to have a more complete picture of why dueling ceased to be a practical method for resolving gentlemanly disputes, we need look no further than the open spaces surrounding Britain's expanding cities and the use that was made of these parks and commons in the second half of the nineteenth century. It was not only the Volunteers whose target practice signaled Britain's preparedness for war. In the proliferating playing fields of Victorian Britain was the next generation of gentlemen playing healthful sport. As one Scottish newspaper observed in 1865, for students in Europe “the duel supplies the place which cricket and boats hold among English youth.”Footnote 136 Gentlemanly identity was to a degree democratized, but it was more importantly brought into clearer alignment with the ambitions of the nation rather than the interests of any single class group. This synergy was accomplished not by a sea change from an aristocratic to a middle-class ideal of masculinity but rather by the selective preservation of those martial values that were the most profitable to the nation.