In 1629, Samuel Sharpe embarked from Gravesend for New England bearing an unusual object: a silver seal dye for the colony of Massachusetts Bay. Seals were commonplace enough, an ancient and ubiquitous technology for certifying authority.Footnote 1 This seal was unusual, however, in two respects. First, it represented the emergence of a new kind of authority in the Atlantic world: English colonial government. This form of authority was very much a work in progress, with some precedent in the English conquest of Ireland but with ill-defined and shifting relationships between local and central authorities, multiple forms of organization, and varying legal justifications.Footnote 2 Second, like its sibling for the colony of Plymouth, the seal of the Massachusetts Bay colony depicted an Indian. The placement of an Indian on a great seal of English government was unprecedented in a space traditionally reserved for images of monarchs, aristocrats, and other symbols of the late feudal order. These two exceptional details were, in fact, linked: in the coming decades, colonial leaders would increasingly turn to legal representations of Indians on seals as expressions of how to resolve questions of legitimate authority that emerged alongside the development of their Atlantic empire. Between the creation of the Massachusetts and Plymouth seals and the conclusion of the Seven Years’ War nearly a century and a half later, images of Indians rose and fell on the great seals of the British Atlantic colonies. At the peak of this process, the Indian was the most persistent bureaucratic icon of the British Atlantic save the arms and image of the monarch himself, certifying authority from Halifax to Kingston, Jamaica.Footnote 3

Indians did not appear on all seals, but where they did, their images reveal a rich and varied iconographic imperial discourse on the relationship between European ideas about Indigenous people and just claims to colonial authority. Paradoxically, while the purpose of seals was to ensure legal conformity across time and space, in their totality they reveal an empire of inconsistency—a variety of unsettled answers to problem-space of settlement.Footnote 4 The Indian of the Massachusetts Bay Colony seal had no conceptual analogy outside of New England, for example, and even within New England colonies was a contested conception of Indian-settler relations. More generally, colonial seals suggest many contours in this broad process of constructed settlerism.

This essay explores those contours. I begin by examining the meaning of seals as a distinctive discursive space within the British Empire, situating the appearance of “the Indian” on early Stuart seals in the context of European visual culture and colonial ideology. I then trace three periods of seal development. In the early decades, seal logics of Indian depiction varied depending on colonial governance structure and local and regional circumstance. Indians on seals mattered in relation to the land, as a form of colonial metonymy that positioned and repositioned them as needed: recipients of Christian rescue, valued neighbors, bitter enemies, trade partners, and vassals. During the period of the late Stuart government reform and consolidation, by contrast, the crown standardized Indian images, framing them as exotic vassals offering fruits of the land. Under the Hanoverians, new seal depictions of Indians shifted again, and Indians joined classical gods and demigods, as well as Britannia herself, to allegorize New World places, until eventually images of the land replaced Indians altogether.Footnote 5 The one constant in these depictions across centuries and across colonies was the Europeans’ iconic exclusion of Indigenous peoples from full civic constituency within the colonial life. Seals depicted a range of solutions to the shared settlement problem of claiming the land, but not the people.Footnote 6

Indigenous people occupied a central place in the culture, politics, and law of the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century British Atlantic empire. Whether it was the seventeenth-century Massachusetts preacher John Eliot, who hoped to “Coyn Christians” out of the Algonquian peoples, or Jefferson's Notes on the State of Virginia a century and a half later, Europeans and Euro-Americans said a great deal about the relationship between Indians and just claims to European settlement. Legal proceedings and imperial regulatory language reveal ongoing struggles of imperial authorities, settlers, and Indians themselves to deploy and reframe notions of subjecthood rooted in evolving legitimacy claims to colonial projects.Footnote 7 The contours of the problem-space of early modern European settlement vis-à-vis Indigenous people can be seen outside of print discourse, too, in a variety of other media and public performances. Historians in recent years have made innovative study of the ideas implicit in descriptions and depictions, in architecture, print culture, maps, costume books, theater, and public ritual.Footnote 8

Surprisingly, aside from the occasional use of an individual seal for illustrative purposes, there is little scholarship on the development and historical significance of colonial seals, whether as art history, material culture, legal arguments, or policy instruments. Most extant research on seals qua seals focuses on medieval seals or grows out of the antiquarian tradition, collecting and cataloguing bodies of images, explaining their internal logic according to the rules of heraldry, and carefully accounting the specific dates and bureaucratic details of each one's creation.Footnote 9 Several nineteenth- and early twentieth-century historians and state historical societies launched cursory (and often erroneous) investigations into the colonial origins of their state government seals.Footnote 10 In the later twentieth century, Peter Walne and Conrad Swan offered more serious and systematic analysis, though they each continued the antiquarian tradition, focusing on the bureaucratic details of seal creation and their literal rather than contextual meaning. Two notable recent exceptions have examined individual colonies: Cathy Rex's analysis of the cultural meaning of seventeenth-century reproductions of the Massachusetts Bay Colony Seal and Ben Marsh's close study of the development of the great seals of Georgia.Footnote 11

The dearth of studies is understandable. Once the highest form of state art, seals have faded in significance and memory, a decline already in evidence in the eighteenth century.Footnote 12 Tracking them down and detailing their creation are daunting tasks appealing more to the taste of philatelists and numismatists than to that of historians. Colonies had a high rate of failure; some were unauthorized, and even among authorized colonies, bureaucratic channels for recording seals depended on the type of colony and the details of its charter. Indeed, the pioneering work of Walne and Swan included, there is no single, comprehensive collection (never mind a scholarly historical study) of the deputed great seals of the British Empire. In making this study, I have assembled and drawn upon the first complete collection of colonial seals of the British Atlantic.

The primary work of seals as a discursive space was the promotion of legal and political legitimacy. In The Great Arch, Philip Corrigan and Derek Sayer argue in the Weberian tradition that the idea of a state is a claim to legitimacy, a form of “politically organized subjection.”Footnote 13 In this way, colonial seals of the British Atlantic did the literal work of stamping just authority upon state documents with the symbols of the political/legal work that sustained it. Seal icons and the differing conceptions of legitimacy that they projected were “intersubjective,” explains Robert Bliss, “the outcome of collective agreement often enshrined in complicated procedural rules, and were not under the control of single individuals.”Footnote 14 Settler companies, patentees, court officials, foreign governments, and Indigenous Americans were all implicated in the logics of legitimacy.Footnote 15 Likewise, as the nature of the British Empire changed over the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, shifting the gravitational point of origin of the intersubjective process of seal formation away from the colonies and toward Whitehall (and, simultaneously, a global scope of vision), the range of legitimizing logics within seal iconography shifted with it.Footnote 16

Why did Indians appear first appear on colonial seals in the early seventeenth century? While individual proprietors drew from the well of heraldry, and its signifiers of legitimate authority affixed their status in the late medieval social order, chartered companies and later offshoots situated their legitimacy claims in relation to the people occupying land they coveted. By the 1620s, “the Indian” circulated in England and Europe as a dynamic, yet widely recognizable set of visual cues with multiple meanings that could serve those claims.Footnote 17 These visual technologies reflected over a century of early modern European ethnographical discourse on their relationship to the peoples of the Americas. The idea of nations of people living on unknown continents caused epistemic disruptions in established conceptions of time, space, theology, and human nature, resulting in a variety of imaginaries against which Europeans could reposition themselves in an age of (for them) global discovery and conquest. This sixteenth-century discourse propelled written accounts, images, and even the captive bodies of Americans into European visual and popular culture, and, importantly, into state-related imagery in maps, court events, and colonization propaganda.Footnote 18 These framings, connecting Indigenous Americans to place, race, and history, “informed [European] juridical reflections on how the New World should be administered,” observes Surekha Davies.Footnote 19

Three sixteenth-century developments in particular gave shape to early seventeenth-century visual discourse. One of the earliest, and most enduring, was the bad Indian/good Indian dichotomy that deployed, alternatively, monstrosity and cannibalism as a markers of Americans’ inhumanity and qualification for enslavement, versus innocence and tractability as markers of common humanity. In the former case, drawing on classical and medieval tradition, European artists depicted some Americans as literal monsters—giants and cyclops, men with no heads or dog heads—although these depictions had declined by the 1620s. A more durable bad Indian, which originated with descriptions of the Tupinamba people of Brazil, wore a feathered crown and bustle and practiced cannibalism, signaled by the presence of human body parts. This image became the default representation for all the peoples of the Americas, dominating map depictions of Indians until the later sixteenth century, when it was joined by the good Indian (not a cannibal), and enjoyed wide circulation until the mid-seventeenth century.Footnote 20 A second, related development in the European visualization of the Americans began in the 1570s, as images of female Indians appeared in European maps and travel-related print matter as allegories for the continent “America.” The signification included still-familiar Tupinamba icons: the feathered crown and bustle, bows and arrows, and often, human body parts.Footnote 21

A third development reflected the humanist tradition of naturalistic depiction, which accounted for the impulse to characterize and categorize accurately, even as this impulse sat in tension with the propagandistic purposes and mimetic practices of depiction.Footnote 22 Stephanie Leitch has located this impulse in early sixteenth-century German language printmaking, but it was the emergence of “eyewitness”-style depictions of North American peoples at the turn of the seventeenth century in the publications of Theodore De Bry that provided another popular set of visual tools to English colonizers. These included prints based on the watercolors of artist John White, which made available detailed depictions of North American people's bodies and everyday cultural practices by a trained artist.Footnote 23 As had been true in the sixteenth century, however, these “naturalist” attempts were themselves transformations—Anglicized both in conceptual framing and reproduction. Nevertheless, De Bry's publication of White's work in his America series (1590–1634) provided visual source material for English colonial propagandists and potential seal makers.Footnote 24

This pliable but easily recognized visual discourse was well suited to the particular types of legitimacy claims that seventeenth-century English charter companies required. A female figure could be Indianized through the presentation of her body and accoutrements to represent America as a place; a male figure (with or without female accompaniment) could be Indianized similarly to represent Indians as a class of people.Footnote 25 Moreover, other cues could frame Indians as more or less human, more or less civilizable, more or less Christian, more or less subject to English law. Alternatively, artists could also depict a particular Indian people through use of clothing “in the habits of their [particular] country,” as did a 1638 coat of arms granted to the Company of Adventurers to Newfoundland.Footnote 26

As indicators of just claims to authority, seals of the seventeenth-century British Atlantic positioned the Indian along two strands of imperial legal theory rooted in Roman law: dominium (just claim to the land) and imperium (just power to command the land's inhabitants).Footnote 27 The distinction between the two was central to the difference between charter and royal colony seals in particular, while they also reflected tensions over subjectivity within the empire—between settlerist preoccupation with direct authority over Native American relations and clear distinctions between English and Indigenous subjective privileges and identity.Footnote 28 Charter colony seals used images of Indians to justify the settlement of Indian land, not the conquest, subordination, or enslavement of Indian peoples, although English settlers engaged in all three of the latter. Charter colony seals were not for Indians in a constitutive sense—the Indian was not depicted as the normative or ideal citizen of the colony, nor as a tributary subject. Instead, images of Indians on seventeenth-century charter colony seals represented claims to dominium—the right to the land that the Indians occupied. Royal colony seals, by contrast, depicted Indians in relation to the political economy of the empire, fixing them to the resources of the land as vassals or as well-regulated trade partners. The improvement of these Indians was not central to the claim of authority, nor was their full integration as civilized participants in emergent notions of British identity. Nevertheless, royal colony seals depicted a composite colonial relation—Indians as subjects themselves, represented by a link to the raw materials characteristic of each colony—offering fur in Nova Scotia, lumber and fur in New York, tobacco in Virginia, and fruit in Jamaica.

Within these general patterns, further nuances emerge in the meanings ascribed to Indianness and imperial authority. Terra nullius, the much-touted doctrine of rightful settlement by virtue of empty (unimproved) land, was but one of several legitimacy claims depicted in deputed great seals and was itself understood through multiple lenses. For example, Indians first appeared on the seals of Puritan New England colonies positioned within a Protestant framework rooted in scriptural authority—settlement for salvation. In these depictions, Indians lived in an Edenic state of nature and were in desperate need of rescue—a reinforcement of the agriculturalist justification for dominium on the basis of Indian nonuse of land. Within a decade, however, other charter colony seals appeared in New England that challenged or upended this notion. The seal design for Newport, probably intended for the colony of Rhode Island, symbolized Roger Williams's full rejection of evangelical and agriculturalist arguments for dominium, while the seal of Connecticut suggested the hand of God in land clearance—either by plague or just war. Struck during the reign of Charles I, these images reflected the fluid nature of the early seventeenth-century British Atlantic, where layered sovereignty (and royal dysfunction) allowed chartered private groups like the New England Company relatively wide latitude in their self-governance and relations with Indigenous people.Footnote 29

Outside of New England, Indians emerged in the great seals of proprietary and royal colonies after the Restoration, following a general trend of imperial organization and consolidation. Initially, Indians appeared as “supporters” in the heraldic tradition, highlighting secular themes of the imagined colonial political economy, in which the extension of dominium despite the presence of Indigenous peoples was justified through their inadequate land use and primitive social organization, while the introduction of settler colonies promised prosperity to those Europeans who participated. Soon, however, the crown incorporated a different visual device: emphasizing Indians as subordinate and tributary. That vision—Indians on their knees offering goods—spread across the British Atlantic from New England to the Caribbean and became a standard visual depiction for late Stuart royal colonies.

Yet these depictions and the ideology behind them were not stable either. Under the Hanoverians, the use of Indians as icons of empire changed to reflect a revolution of colonial print and pictorial discourse that mirrored the broader shift in political discourse in the Walpolean era.Footnote 30 While the Hanoverians maintained icons of existing colonies, new ones took on increasingly classical and abstract characteristics until, at the conclusion of the Seven Years’ War, they disappeared altogether from new designs, replaced by depictions of territory in the form of maps or landscapes that coincided with broader changes in territoriality within legal discourse and legitimation.Footnote 31 Legitimacy claims in seals for colonies shifting from charter to royal control (South Carolina, Georgia) focused on the tension between liberty and imperial authority. Others celebrated the expansion of imperial territory in mid-century global wars. By the time Indians emerged in popular and state iconography among white settlers in revolutionary-era North America, their place in British imperial seals was already on the wane.

An analysis of seals must begin with their meaning as technologies of governance. Before the modern era, seals were physically, legally, and figuratively legitimizing instruments of authority. Elaborate images pressed in clay or wax, on paper, or in special ink, seals had for millennia authenticated written documents and prevented tampering in transit, allowing rulers to impersonalize (and thereby spread) their authority across branches of government and across space. In early modern England, laws and rituals emerged around the use of seals to protect this function. Legal documents were merely ink on parchment without the appropriate seal, and keeping the seal dye safe required an official and honored position within government. Indeed, a seal dye could take on a political life of its own. When John Blackwell took the governorship of Pennsylvania in 1688, for example, his Keeper of the Seal, Thomas Lloyd, used an overly broad interpretation of the keeper's duties as a form of veto over the new governor's actions: only the keeper, Lloyd argued, could decide whether to actually apply the seal to documents. As a result, observed a councilman, “We have two Goverrs & two Councils.”Footnote 32 At the same time, back in England, the abdicating James II was said (famously and perhaps apocryphally) to have tossed the dye for the Great Seal of England into the Thames to embarrass any new government.Footnote 33

Seals were more than physical and legal authenticators, however. They were an art form that deployed symbols communicating just claims of authority. Such symbols of sovereignty weighed heavily in the iconography of the great seals of England and early modern Europe. Complex heraldry established a ruler's pedigree and prowess, upon which rested his or her claim to the throne. Thus seal images and their logic were rooted in an emerging early-modern discourse of divine right of kings, subjective rights, and international diplomacy. Among the monarchs of England and the United Kingdom, long tradition held that the Great Seal of England should be two-sided, with the monarch seated on a throne on one side and on horseback on the other. Around the edges, Latin inscriptions stated the ruler's full title and motto. In their seal portraits, monarchs wore and bore symbols usually reserved for coronations and key functions of state: crowns, scepters, orbs, and other regalia. The audience for a monarch's great seal would be anyone reading formal state documents, from state officials to members of Parliament, local aristocrats and sheriffs, to foreign dignitaries and heads of state, to the audiences of common people hearing a document read aloud or seeing it posted, a two-sided wax puck dangling from the parchment by its telltale bright red ribbon, the forerunner of our modern expression “red tape.”

Deputed seals, those struck for use by the second tier of empire—governors of royal colonies, proprietors, and charter companies—initially fell within these general conventions and served similar functions for similar audiences. Yet there were no rules or traditions per se governing the seals of Atlantic colonies, as they were something legally and conceptually novel. Usually colonial seals were, like great seals, two-sided wax disks covered in paper, around four and a half inches in diameter, suspended from a document by red ribbon. In other cases, however, colonies employed single-sided disks approximately four inches in diameter.

As a bureaucratic technology critical to a functioning government, seals were expensive to manufacture, carefully designed, scrupulously used, and jealously guarded. Like a computer password today, their authenticity depended on their complexity. The resulting artwork produced by gravers, usually on silver dyes, formed a discrete but permeable form of visual discourse. As a matter of substance, seal depictions followed conventions internal to their genre: placement and signification of text, use of heraldic elements, and legal context. As a matter of style, however, seal artwork often reflected the conventions of its age and constituency: seventeenth-century New England colony seals, for example, resembled the style of popular and nonconformist print matter; mid-eighteenth-century royal colony seals deployed the undulating forms of rococo.Footnote 34

Reflecting the incoherence of the early colonial enterprise, colonial seals had no single bureaucratic apparatus to govern their manufacture. Under Queen Elizabeth, there was no need. The series of failed colonial ventures during her reign produced no specific seals. Under the early Stuarts, however, colonial ventures began succeeding (if barely). Colonies were of two basic types. Royal colonies were ruled directly by monarchs as part of their estate. Monarchs selected the governors of these colonies, and the seals, known properly as deputed great seals, were designed centrally by the same graver of the great seal of England. The accession of a new monarch required new deputed seals, since these usually bore that person's name and likeness, as well as heraldry. These seal designs were discussed and approved by several bureaucratic bodies that emerged by the end of the seventeenth century: the Colonial Office, the Board of Trade and Plantations, and the Treasury. The Royal Mint, moreover, was charged with auditing seal contracts to verify that the workmanship and weight in silver were worth the price charged, and beginning in the early eighteenth century, it kept a collection of first wax impressions of royal colony seals. (There was no other formal connection between the mint's coinage duties and the making of seals, however.) In practice, colonial governments with two-sided seals used one side or the other, or both, depending on the type of transaction.Footnote 35

Charter colonies, on the other hand, were ruled by companies and boards of trustees, or by proprietors who acted as feudal lords. Their powers and the rights of their inhabitants were spelled out in their charters, if they had them, which sometimes specified the details of the colony seal. Charter colony leaders were responsible for paying for their proprietary and company seals, which were often less skillfully rendered as a result. In the case of seventeenth-century Massachusetts, for example, the seal went through several local engravings of varying quality and fidelity, including, potentially, a sex change.Footnote 36 As a result of their ad hoc origins, charter colony seals are difficult to account for today.

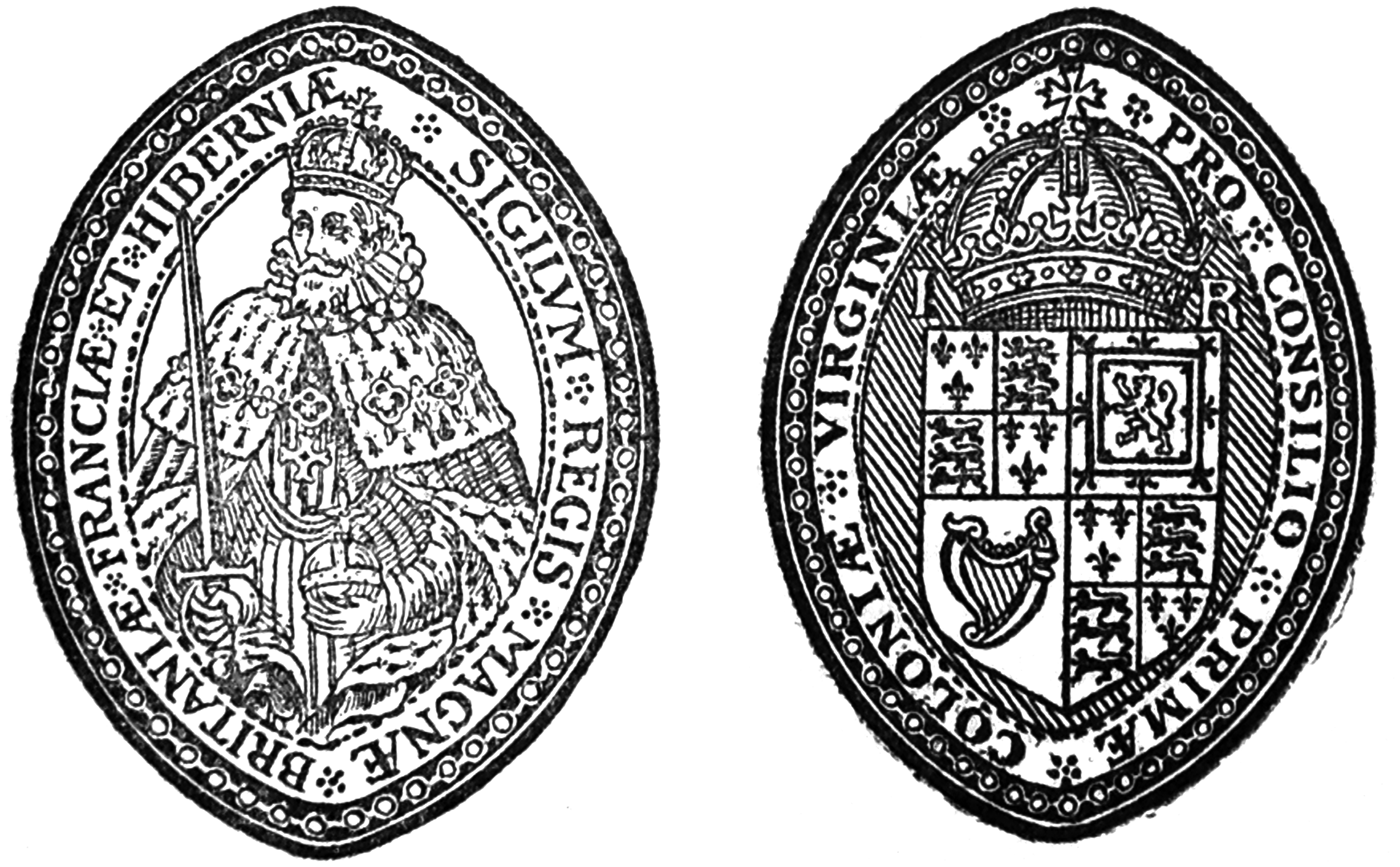

For most of his reign, James I (r. 1603–1625) carefully regulated colonial seals following medieval conventions. In the charters for the two Virginia companies, as well as the colonies of Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, James authorized seals, “Each of which . . . shall have the King's Arms engraven on the one Side thereof, and his Portraiture on the other.” Around the border of each was written, on one side, “Sigillum Regis Magne Britanniae, Franciae, & Hiberniae (Seal of the King of Great Britain, France, and Ireland), while on the other side the inscription indicated whether it was a local seal or one of the Supreme Council (figure 1).

Figure 1 Seal of the First Council of Virginia (1606), in use by Virginia Colony until 1652. With the exception of the inscription on the reverse, similar seals were authorized for Newfoundland (1610) and Nova Scotia (1622). Source: Lyon G. Tyler, “The Seal of Virginia,” William and Mary Quarterly 3 no. 2 (1894): 81–96, at 83.

James was not entirely consistent, however. He chartered two other colonial ventures during his reign that would require seals: Somers Island Company (Bermuda) in 1615 and the Plymouth Council (New England) in 1620. In the former case, he authorized the company to create its own corporate seal by which to govern. There were no human inhabitants of Bermuda when the Virginia Company's flagship, Venture, shipwrecked there. In 1635, the Bermuda Company was granted a fitting coat of arms, a shipwreck, under which the colony conducted its affairs.Footnote 37 In the case of the Plymouth Company, the New England Charter of 1620 specifically empowered the company to make whatever seals it found necessary for the public government of its colonies. Not until after James's death, however, did the Plymouth Council or the crown authorize any more seals.

As colonization efforts began to succeed—a process accelerated by the end of war with Spain in 1630—seal design shifted from coherent medieval notions of legitimacy under James I to an incoherent patchwork under his son Charles I. Caribbean proprietary colonies were in political turmoil due to conflicting patent claims, and many were uninhabited by Indigenous peoples. Two proprietary colonies, Maryland (1632) and New Albion (1634, in present-day New Jersey), adhered to medieval tradition, bearing the effigy of their proprietor on one side and his arms on the other. Puritan colonies framed their legitimacy claims in biblical terms. For example, the seal of the Caribbean colony Providence Island (1630) depicted three islands surrounded by waves, with motto from Isiah 42:4, Legem eius insulae expectabunt (The islands shall wait for His law).Footnote 38 It was the Puritan colonies of New England that pioneered the use of Indians on seals—two explicitly, one symbolically, and one implicitly. They were the only seals anywhere in the British Atlantic to reference Indians before the English Civil War.

Negotiating the legal relationship among the Indigenous groups in New England, colony government, the crown, and rival (primarily Dutch) empires was critical in the early decades of the region.Footnote 39 The first two seals were made in 1629 by Massachusetts Bay (figure 2) and Plymouth Colonies (figure 3), both of company design. Plymouth was already nine years old when it crafted its seal, having waited for a charter from the Plymouth Council for New England. Both colonies were organized and governed by Protestant dissenters, though they contained many settlers who were not. The Plymouth group had previously fled England for Leiden, in South Holland, before seeking refuge in America. The Congregationalists who settled Massachusetts Bay, by contrast, sought reconciliation with the Church of England and hoped to return to England. Despite their differences, both colonies produced strikingly similar seals that focused on Indians as objects of evangelism.

Figure 2 Seal of the Governor and Company of Massachusetts Bay in New England (1629), reproduction. Source: Nathaniel B. Shurtleff, ed., Records of the Governor and Company of the Massachusetts Bay in New England, 5 vols. (Boston, 1853–1854) (the image is reproduced on the cover of each of the five volumes). There is no evidence to corroborate whether this nineteenth-century print was an attempt at an exact representation of a now lost original (1629) image or whether it was a copy of later seventeenth-century versions. The iconography did not vary among versions.

Figure 3 Seal of the Colony of Plymouth, New England (ca. 1629), reproduction. Source: Samuel Adams Drake, Nooks and Corners of the New England Coast (New York, 1875), 267.

The Massachusetts Bay seal is unambiguous in its argument that the colony's just claims to authority are rooted in scripture. It shows a figure holding a bow and arrow, wearing leaves about his waist, standing in a field with two pine trees in the distance, speaking the words “Come Over and Help Us.” Depicting the Indian wearing leaves (not the leather of De Bry's Algonquians nor the feathers of the Tupinamba) evoked the image of Adam in the Garden of Eden, described in Genesis as “Then the eyes of them both were opened, and they knewe that they were naked, and they sewed figge tree leaves together, and made them selves breeches.”Footnote 40 The words “Come over and help us” offer the answer to the problem of possession. The words refer to Acts 16:8–10 (Geneva Bible 1599), in which Paul dreams that a man from Macedonia is begging him to come and preach the Gospel.Footnote 41 The bow and arrow were universal European visual cues of Indianness.Footnote 42 That the words issuing from the Indian's mouth should be in English reflected the Puritan insistence on the use of the vernacular in worship and, like the image of the Indian, were an innovation in seal design. They were not an innovation in print imagery, however, and reflected graphic satire conventions of the time. In this way, the image can also be read as a political statement.Footnote 43 Likewise, the trees appear less as a symbol of something related to just claims of authority than an evocation of the eyewitness style of Indian depiction popular at the time.Footnote 44

Fitting the peoples of North America into the evangelical binary of the savage and the saved ran throughout early Stuart–era colonial patents and charters but gained central prominence in New England. The idea was an old one. “The people of America crye oute unto us . . . to come and helpe them and bringe unto them the glad tidings of the gospel,” wrote Richard Hakluyt the Younger to the queen in 1584.Footnote 45 The reference reflected the theological problem posed by the discovery of New World peoples: how to square them with biblical histories of the world that was known. But it also highlighted another problem central to the colonial project: how to legally (and morally) justify settlement on occupied land. Unlike the Spanish, who drew from their experiences of the Iberian reconquista to organize the conquest and domination of New World peoples, the English focused their energies on claims to the land and viewed Indigenous people with sovereign separation from the settlement process.Footnote 46

The problem of rights of possession of the land hinged, for the English, on two related questions: the Indians’ right to the land according to English custom and law, and the broader problem of territorial claims vis-à-vis other European kingdoms.Footnote 47 Seal images of Indians for the Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, (and later) Carolina colonies (see figure 6, below) answered both questions by appealing to the English common law tradition that unimproved land could be taken for proper improvement, and to the pan-European Roman legal concept of terra nullius that vacant land could be taken by anyone who would properly occupy it.Footnote 48 It was the vital (and inaccurate) point that Indigenous Americans were not agriculturalists that provided the English with a legitimate legal argument for taking possession of the land in a way that did not violate English law.Footnote 49 In their ceremonies of possession, Patricia Seed has observed, the English went to great lengths to engage in behaviors that demonstrated their proper use of the land.Footnote 50 The “Indian” as an invented class of person lived in a state of pre-civilization that obviated claims of possession. Thus images of Indians wearing clothing, farming, living in settled villages, or engaging in the habits of “civil” society, all available at the time, would not do, even if such images appeared in pro-colonial propaganda for other reasons.Footnote 51

The English were not comfortable with the agriculturalist idea by itself, however, and in several instances early Stuart charters carefully emphasized that the land was not just vacant by virtue of being uncultivated but was actually unoccupied—not an Indian in sight. The 1610 Letters Patent for Newfoundland emphasized that the land was “so destitute and so desolate of inhabitance that scarce any one savage person hath in many years been seen in the most parts thereof,”Footnote 52 while the petition of the Northern Company of Adventurers for a charter to settle New England assured its reader of “the utter Destruction, Devastation, and Depopulation of that whole Territory” by disease. After listing the many justifications for colonizing New England, the petition concluded, “We may with Boldness go on to the settling of so hopeful a Work, which tendeth to the reducing and Conversion of such Savages as remain wandering in Desolation and Distress, to Civil Society and Christian Religion.”Footnote 53 The doctrine of terra nullius, historian Andrew Fitzmaurice observes, was not the only natural right—so, too, were friendship and trade.Footnote 54 Christian benevolence toward the Indigenous people, fellow “sons of Adam,” found purchase in the rhetoric of early Virginia settlement, too, though it soured in the wake of the 1622 Powhatan massacre of over three hundred settlers.Footnote 55 Saving Indians from the Spanish also weighed in the equation of legitimate English settlement.Footnote 56

The seal of Plymouth Colony contained similar elements to that of Massachusetts Bay. The figure of an Indian is depicted four times, in the quadrants of a cross. He is naked or perhaps wearing a loin covering, kneeling on one knee in a field with trees in the distance. He holds a burning heart, a reference to John Calvin's personal seal, a hand holding a heart. The motto of Calvin's seal was Cor meum tibi offero, Domine, prompte et sincere (I offer my heart to you, Lord, readily and sincerely). The founding date of the colony, 1620, appears at the top. The cross signifies Saint George's Cross, the symbol of England, inherited from the Crusades, which also evoked the struggle against heathenism. The nondescript trees echo those of the Massachusetts Bay seal.

To put Indian bodies on a seal of government was unprecedented. But the Indian's centrality in the image did not signify that the primary function of the colony was to dominate Indigenous peoples either spiritually or temporally, or that the image was a representation of the character of the colony. Moreover, while seal iconography might align with colonialist propaganda, which Chaplin has suggested was the purpose of the Massachusetts Bay seal in order to “solicit funds, personnel and other support for a puritan venture in America,” seals were foremost a form of political and legal discourse in legitimacy.Footnote 57 Governor John Winthrop framed the problem thus: “What warrant have we to take that lande which is and hathe been of longe tyme possessed by other sonnes of Adam?” He gave four answers: “[1:] That which is common to all is proper to none, these salvage peoples ramble over much lande without title or propertye: 2: there is more then enough for them and us; 3: God hathe consumed the natives with a miraculous plague, wherby a great parte of the Country is left voyde of Inh[abita]nts. 4. We shall come in with good leave of the natives.”Footnote 58 The image of the Indian, a son of Adam without knowledge, alone and asking for help, serves in Winthrop's discourse as an embodiment of just claims to dominium wrapped in the Protestant scriptural interpretation. The seal image was Winthrop's warrant.

Once settled, however, New England colonies and colonists generated compelling new arguments for legitimate dominium elsewhere. Within a decade, splinter settlements and colonies formed throughout New England; these coalesced by mid-century into New Hampshire and Maine (both under the tenuous authority and seal of Massachusetts Bay), New Haven (which had no seal or charter), Rhode Island, and Connecticut. The seals of the latter two colonies indicated new arguments for legitimacy in relation to Indigenous peoples.

In 1641, Newport (settled 1639) formally adopted a hand-held seal for use “by the state,” depicting a sheaf of arrows bound with a thong, surmounted by the words Amor Omnia Vincit (Love conquers all). The settlement at Newport was led by William Coddington, who had been encouraged to leave Massachusetts Bay by Roger Williams, and settled on land scrupulously purchased from the Narragansett nation, with whom the dissenting white settlers under Williams's umbrella enjoyed friendly relations. No documents survive with the seal imprint, and it is not clear that this seal was ever made—Coddington and Williams probably waited for authorization from the Patent for Providence Plantations, written in 1643 and ratified by Parliament the following year, which united Newport with Providence and Portsmouth and authorized the inhabitants “for the better transacting of their public Affairs to make and use a public Seal as the known Seal of Providence-Plantations, in the Narraganset-Bay, in New-England.”Footnote 59 No seal was made until 1647, however, when the united colony adopted an anchor as its seal; images of it still survive, and it has formed the basis of the Rhode Island seal ever since (figure 4).Footnote 60

Figure 4 A later imagining of the original 1641 seal design of Newport, edited from a drawing by the Newport Historical Society. Source: Eugene Zieber, Heraldry in America (Philadelphia, 1895), 181. The banner reads Amor Vincet Omnia (Love conquers all). (No image or copy of the original seal survives, and it is possible that it was never was made.)

We have no direct evidence of the intended meaning of the 1641 Newport seal. Strong circumstantial evidence, however, suggests that its meaning related to the insistence of colony leaders on friendly and honest dealings with the Narragansett. Roger Williams's critique of the illegitimacy of the Massachusetts Bay colony's church and government, which led to his banishment, began with his insistence that the colony charter had not been legally granted and that (as John Winthrop accused and Williams agreed) English settlers “have not our land by patent from the King, but that the natives are the true owners of it, and that we ought to repent of such a receiving it by patent.”Footnote 61 The Patent for Providence Plantations, by contrast, staked the legitimacy of the colony's claim of dominium on the justice of plain dealings with the Narragansett—by treaty—and not by deploying agriculturalist or evangelical arguments about their deficiencies. Such a move took for granted the legitimacy of Indian claims to the land, and thus their ability to sell it: “And whereas divers well affected and industrious English Inhabitants, of the Towns of Providence, Portsmouth, and Newport . . . have adventured to make a nearer neighborhood and Society with the great Body of the Narragansets, which may in time by the blessing of God upon their Endeavours, lay a sure foundation of Happiness to all America. And have also purchased, and are purchasing of and amongst the said Natives, some other Places, which may be convenient both for Plantations, and also for building of Ships Supply of Pipe Staves and other Merchandize.”Footnote 62

Williams and the small movement he represented repudiated the logic of the Massachusetts Bay Colony seal while nevertheless embracing the same basic function: to embody and certify the colony's just claim to dominium. Moreover, the positive relations with the Narragansett proved pivotal to English success in the Pequot War, a nettlesome if convenient reality for Massachusetts Bay authorities. As Williams remarked later, “It was not price nor money that could have purchased Rhode Island. Rhode Island was purchased by love”: “by the love and favor which that honorable gentleman Sir Henry Vane and myself had with that great sachem, Miantonomo, about the league which I procured between the Massachusetts English, etc., and the Narragansetts in the Pequod [sic] War.”Footnote 63 A bound sheaf of arrows surmounted by the words “love conquers all” would be quite consistent with such just claims of authority. It also represented the interests of the Narragansett sachems.Footnote 64 The trial and effective execution of Miantonomo in 1643 by the Commissioners of the United Colonies while Williams was securing the patent in London in 1643, however, provides a likely explanation for why the Newport design was never used; it was later changed to a hopeful depiction of the colony's maritime economy.

The Connecticut seal likewise has no recorded direct statement of intended meaning but is very likely a reference to relations with Indigenous people of the Connecticut River Valley. The just claim to authority rests neither on agriculturalist arguments, nor on just purchase and friendly alliance, but with divine intervention in the clearance of land for settlement either by plague or through warfare (figure 5). The seal depicted fifteen grapevines with a hand reaching down from the sky holding a banner reading Sustinet Qui Transtulit (He who transplants, sustains). The transplanted grapevines refer to settlers from England and Massachusetts who flocked to the Connecticut River Valley during the 1630s on the heels of a devastating smallpox outbreak among Indigenous communities, and who planned a wave of further migration from England.Footnote 65 (It failed to materialize.) The seal was originally brought from England in 1639 to Saybrook, a small fortified settlement on the Southern New England coast, the site of the planned migration. It was soon adopted by Connecticut in 1644, to whom the Saybrook leadership sold their stake, including the seal. The motto is a likely reference to passages in the 80th Psalm, 8–9, 14–16 (Geneva 1599) “Thou hast brought a vine out of Egypt: thou hast cast out the heathen, and planted it. Thou madest roume for it, and didest cause it to take roote, and it filled the land.”Footnote 66

Figure 5 The Seal of Connecticut Colony (1639). Source: Zieber, Heraldry in America, 116.

Whether the motto was a reference to the smallpox outbreak or the further land clearances that resulted from war with the Pequot in 1637–38 is not clear.Footnote 67 Saybrook itself had been the site of heavy casualties and siege. The war culminated in the infamous 1637 massacre at Mystic, in which hundreds of Pequots, the majority of them women and children, were killed when the English set fire to their fort. In his personal account of the incident, Major John Mason recalled, “But GOD was above them, who laughed his Enemies and the Enemies of his People to Scorn, making them as a fiery Oven.”Footnote 68 Mason's firsthand account resembles the psalm's central image of God's hand looming above the burning and the planting—an image captured in the seal iconography and biblical allusion. The massacre was a decisive turning point in the war, and soon the English, aided by the Narragansett, broke Pequot power in the region, claimed their lands, and distributed some survivors as slaves.Footnote 69 Said Mason, “Thus the LORD was pleased to smite our Enemies in the hinder Parts, and to give us their Land for an Inheritance.”Footnote 70

By the end of Charles I and his reign, New England's colonial seals had placed Indians at the center of just claims of authority but had done so in multiple, contradictory ways. God smiting hinderparts and allocating land was not a typical terra nullius argument, although God setting a plague among the heathens was. But like the Edenic agriculturalist visions of Massachusetts and Plymouth, it depended on the projection of dysfunction upon the Indian—the heathen. Neither of those authority claims, however, comported with Rhode Island's Newport Seal, which saw square dealings with the Narragansett, and not their debasement, as the basis of its claim.

The English Civil War and interregnum governments brought a halt to new seal production for the colonies. This was not for lack of policy on the part of the Commonwealth or upheaval within the Atlantic world, both of which were transformative to the organization of colonial governance.Footnote 71 Charles II and James II resumed granting charters to proprietors, but not colonization societies, acquired new (royal) colonies, and consolidated old ones. The Indian emerged as a new symbol of colonization, while the old Puritan Indian icons of Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, and (briefly) Connecticut were quite literally erased. This new Indian not only looked different; he and/or she (depending on the seal) signaled a different version of colonial ideology. The guiding aphorisms of late Stuart seal mottoes came not from the Bible but from classical republican writers. Royal colonies adopted images of Indians as subordinates, integrated into the political economy of the Atlantic economy. Some proprietary colonies followed suit or eliminated Indians altogether, focusing instead on the benefits of the colonial political economy to European colonists.

When Charles II ascended to the throne, this new Indian appeared in two seals nearly simultaneously: the seal of the Province of Carolina (1663), and that of Jamaica, wrested from Spain 1655 and brought into formal governance in 1662. The double-sided Carolina seal (figure 6) followed the typical pattern of a proprietary seal, but because it belonged to eight proprietors, not one, it also resembled the seal of a chartered company, containing a novel iconographic element that belonged to no single individual. On the reverse side appeared a ring of eight escutcheons (the central component of a coat of arms and the typical element of a personal seal) surmounted by coronets. The obverse pictured a complete achievement of a coat of arms designed specifically for the colony itself—crossed cornucopia on a shield, surmounted by a helm, crested by a buck. To the right of the shield, an Indian woman holds a baby in her arms, and beside her a boy holds an arrow, point down; on the other side an Indian man holds a large arrow (or spear), also point down. Both figures are bare chested, wearing aprons of ambiguous material and crowns of feathers (the woman's with but one). The motto Domitus cultoribus orbis (Tamed by the cultivators of the world) highlights the agriculturalist argument for empire building in North America: Indians did not make proper use of the land and did not have sufficient political institutions to hold claim to their territory. The cornucopiae represented the plenty that the land would yield. Whether the Indians, or the land, or both are to be tamed, however, is visually ambiguous.

Figure 6 The two sides of the Seal of the Province of Carolina (1663). Source: J. Bryan Grimes, The Great Seal of the State of North Carolina, 1666–1909 ([Raleigh,] 1909), 5, 6.

The 1663 charter of the colony clarifies the significance of the Indian. The charter begins by delineating the nature of the proprietors’ claim to the territory of Carolina, followed later in the document by a description of the scope of their power to govern the people of that territory. Only the former claim, dominium, makes reference to Indigenous people: “[The proprietors] being excited with a laudable and pious zeal for the propagation of the Christian faith, and the enlargement of our empire and dominions, have humbly besought leave of us, by their industry and charge, to transport and make an ample colony of our subjects, natives of our kingdom of England, and elsewhere within our dominions, unto a certain country hereafter described, in the parts of America not yet cultivated or planted, and only inhabited by some barbarous people, who have no knowledge of Almighty God.”Footnote 72 The claim to the land, then, rests on the fact that it is “not yet cultivated or planted.” The fact that the inhabitants are “some barbarous people, who have no knowledge of Almighty God” was not itself sufficient justification for dominium.Footnote 73 Furthermore, the charter makes it plain that the people of the colony, in a constitutive sense, were the settlers—native subjects of England or other parts of the empire. Indians were not such subjects, nor were they relevant to the scope of imperium described in the rest of the document, except as dangerous outsiders or trade partners. The seventh article of the charter, for example, articulated the position of the colony and its settlers within the kingdom by framing their identity in oppositional terms: “And to the end the said province may be more happily increased, by the multitude of people resorting thither, and may likewise be the more strongly defended from the incursions of salvages and other enemies, pirates and robbers.” European settlers, on the other hand, as well as their and their descendants, would be “denizens and lieges of us [the king]” with the same rights and privileges as native-born English people. The document also authorizes settlers to trade with “the natives of said province.”Footnote 74 The 1663 charter did not specify a particular seal design for the colony, however, except to say that the proprietors might use their seals to delegate their authority. Hence the seal design for the colony was quite in keeping with medieval tradition and other proprietary colony seals. Its only exceptional element is the Indian supporters.

In heraldic tradition, supporters could represent all manner of exotic creatures and personages (lions, unicorns, local people, sea creatures), and so the inclusion of Indians in a fully achieved coat of arms on a seal was an innovation but not a radical departure. Municipal, state, and colonial heraldry constituted a loosely regulated form of art but did not have the same legal or discursive significance as deputed seals. Thus we would not expect to see a coat of arms embody ideas about the relationship between colonial authority and Amerindians per se. In the case of Carolina, the choice did appear to comport with the broader characterization of the Indian's place within the colony's just claims to dominium: they represented the locality in allegory, not a polity. The fact that they are represented as a family unit is intriguing (and was a common-enough form of representation in other media) but offers no particular interpretation except perhaps that, unlike the New England Indians, they are not atomized, Edenic, or in crisis.

At the same time of the formation of the Carolina province, the colony of Jamaica received its first English seal (figure 7). It was two-sided and nearly identical on one side to that of Carolina, and the work of same artist, Thomas Simon, chief graver of the mint. On that side appears the new coat of arms of Jamaica, a shield bearing the cross of England (Saint George's Cross) charged with five pineapples surmounted by a helm with an alligator crest—a popular companion to Indian allegories for America.Footnote 75 The supporters are the identical two Indians in the Carolina arms, with the same sartorial convention. Instead of holding children, however, the woman bears a plate of fruit. The man holds a bow instead of a large arrow. Around the edge are the words Ecce alium ramos porrexit in orbem nec sterilis crux est (Behold, the cross hath spread its arms into another world, and beareth fruit). The motto reads, Indus uterque serviet uni (Both Indies will serve one).

Figure 7 The Great Seal of Jamaica under Charles II. Source: George Vertue, Medals, Coins, Great Seals, and Other Works of Thomas Simon (London, 1780), plate 36.

In case there is any doubt about who that “one” might be, the reverse side of the seal depicts an Indian (the woman from the other side) kneeling before the king, whose right hand, the artist explained, “extended towards a present of pine apples, presented to him as the fruits of that country.”Footnote 76 The motto on this side reads Duro de cortice fructus quam dulces (How sweet the fruit the hard rind yields). Taken from Spain in 1655 and governed by a crown-appointed governor from 1662, the colony of Jamaica possessed no founding English charter.Footnote 77 The right of dominium in the Caribbean, as far as the English were concerned, had been obtained through war with another European power. (Indeed, seals for the other English Caribbean possessions henceforth used the iconography of the Admiralty, not Indians). This is the first instance of what would become the standard depiction of Indians in British colonial seals until the mid-eighteenth century: figures kneeling, offering the fruits of their country to the monarch.

This fundamental change in claims to just authority in royal seal iconography comes into sharp relief in what was probably the most unpopular unit of government in the history of the British Empire: the Dominion of New England. Conceived under Charles II and enacted under his brother James II, the dominion consolidated the colonies of New England into a single administrative unit in 1686, eventually adding East and West Jerseys and New York. Settler resistance to the new government was so strong, and the administration so daunting, that the dominion government collapsed in 1689 when news of the abdication of James II led to open revolts. William and Mary reinstated some of the colonies but consolidated Massachusetts and Plymouth, replacing the colonies’ original seals with a single-sided image of the royal arms.Footnote 78

The ill-fated seal of the Dominion of New England followed the basic blueprint for double-sided royal seals established for Jamaica (figure 8). One side bore the royal arms. On the other side, the monarch stands, framed by curtains, holding a scepter in one hand; in the other is a scroll, which he appears to be handing to the other figures. The seal is unique in the British Atlantic, however, in that a kneeling Indian is joined by an English colonist. The Indian, dressed in the now standard iconographic attire of feather crown and apron, offers a bowl of fruit, while the colonist doffs his hat. A cherub flies overhead holding a ribbon with the motto Nunquam libertas gratior extat, which comes from the Greek poet Claudian: Nunquam libertas gratior extat Quam sub rege pio (There is never a more pleasing freedom than under a pious king).Footnote 79

Figure 8 Seal of the Dominion of New England (1686–1689, reproduction). Sources: obverse, William Cullen Bryant and Sydney Howard Gay, A Popular History of the United States, vol. 3 (New York, 1879), 9; reverse, Zieber, Heraldry in America, 142.

It is difficult to overstate the seismic shift in notions of legitimate authority between the former Massachusetts Bay Colony seal, which debilitated the Indian to lift the evangelical colonist, and the Dominium of New England seal, which put them both on their knees, side by side, before a Roman Catholic king. Gone was the primary concern of early seventeenth-century chartered colony seals emphasizing just claims to dominium. Instead, the logic of the seal, and the Indian in it, was self-referential and imperial. Its meaning concerned the ordering of settlers and Indians alike, from the unregulated and ineffective (from the crown's perspective) charter governments of initial settlement to the strong and efficient central force of direct royal rule.

The cancellation of the Massachusetts Bay Colony seal and consolidation of New England were the culmination of long-standing resistance by New England colonies (particularly Massachusetts Bay) against royal authority in church and state, including the Bay Colony's insistence that Indians were directly subject to its own authority and not that of the king.Footnote 80 The move was also part of a much larger process of political purging begun in 1683, when Charles II systematically terminated the charters and replaced the leaders of hundreds of localities (including London itself) that demonstrated strong Whig opposition to his government. The Lords of Trade, the king's advisory council on the colonies, viewed the enforcement of navigation acts and consolidation of control over the New England colonies as necessary for improving trade and ensuring the greater flow of goods to England, including timber, hemp, and mineral resources. The crown viewed New England's Indian policy as a complete failure, blaming colonial ineptitude for the disastrous prosecution of King Philip's War and dysfunctional relations with neighboring Indians. While serving as governor of New York, Sir Edmund Andros found managing New England's Indian problem to be among his chief headaches. His emphasis on healthy diplomacy with Indian nations infuriated Massachusetts officials.Footnote 81

Thus the seal, completed and delivered to Andros in September 1686 for his journey to New England as governor of the newly minted dominion, echoes not merely a promise of protection but the crown's long-standing efforts to reform New England's colonial misrule.Footnote 82 Politically, the handing of the scroll probably signified the concerns of the administrative and legal reform. (Lingering Stuart animosity toward New England for harboring the regicides of Charles I may also have played a role.) The Indian, depicted as a member of no particular nation but as a general concept, offers the fruits of the land and kneels in recognition of imperium, not dominium, a symbol of better-organized Indian relations and not as an object of improvement or salvation. This representation is in sharp contrast with what the colonist offers: a symbolic show of submission (the doff of the hat) that acknowledges the sovereignty of the monarch and, reciprocally, his own status as a subject.

The dominion collapsed with the Glorious Revolution.Footnote 83 William and Mary restored the original colonies but consolidated Massachusetts and Plymouth. The crown neutralized the seal drama by issuing Massachusetts a single-sided one with the royal arms only. For New York, however, the crown created a new, two-sided seal (figure 9). On one side are the royal arms. On the other, once again, is the image of the monarchs standing before bare-chested Indians on their knees. William floats, ghost-like, just behind the more solid Mary, reflecting her status as the legitimate heir of the dynasty. The Indian woman offers Mary a pelt, a reference to the historic fur trade of the colony, while the man offers William a piece of timber. They are dressed as other seal Indians, except that the woman is corpulent and wears a long cloth wrap from her belly to her heels. Their faces gaze expectantly, child-like, to Mary (as does the ghostly William). Mary's sister, Queen Anne, would in turn recreate an almost identical seal for Virginia, replacing the two Indians with one, a woman offering tobacco. In both instances, it is females who bow before the queen. In later versions, male monarchs receive tribute from men (figure 10). A George II seal depicts two males, one apparently subordinate to the other and entirely naked—suggesting social hierarchy and, possibly, slavery.Footnote 84

Figure 9 Left, Obverse side of the Great Seal of the Province of New York, 1691–1705; right, Obverse side of the George II Seal of New York. Sources: William and Mary seal, E. B. O'Callaghan, The Documentary History of the State of New-York, vol. 4 (Albany, 1851), plate 4 (description, “Seal of King William and Queen Mary,” at *2–*3); George II seal, photo from author's private collection. Courtesy of the Royal Mint.

Figure 10 Obverse side of the Queen Anne and George I, II, and III Seals of Virginia Colony. Source: photos from author's private collection. Courtesy of the Royal Mint.

The Restoration seal of Jamaica followed the same pattern, replacing the old version of the Jamaica coat of arms on the reverse with the standard royal arms used to back all double-sided royal colony seals, and putting a small version of the Jamaica arms on the obverse while employing the standard kneeling Indian offering native goods to the monarch (figure 11). By the time of George III, the Indian disappeared from Jamaica's seal, replaced by a solitary African man on his knees—an acknowledgment of the demographic transformation of the island.Footnote 85

Figure 11 Obverse side of the Queen Anne, George I, George II, and George III Seals of Jamaica. Not until George III did seals drop the image of the Indian in favor of an African. Source: photos from author's private collection. Courtesy of the Royal Mint.

A remarkable feature of each of these seals is not just the centrality of the Indian in the image but the abstract quality of his or her relation to its political economy. Notwithstanding the burgeoning trade in enslaved Indian people in Virginia in the 1680s, the role of Indians in the production of Virginia tobacco was not central enough to warrant their depiction on a seal offering tobacco.Footnote 86 Likewise, while the Atlantic trade in enslaved Indian people included Jamaica, the place of the Indian on that seal is clearly that of a representative of the place itself. Only on the New York seals does the Indian offering pelts appear to be central to the role of Indigenous people to the political economy of the colony, although the Lords of Trade expressed great concern over securing the steady supply of timber as well, also depicted.Footnote 87

The Hanoverian monarchs George I to George III maintained the imagery set down by their predecessors for existing colonies. But in cases of new royal colonies, seal art increasingly transformed Indians in the visual discourse of legitimacy or removed them from it altogether. Authority claims related to colonial conversion from charter to royal control rested on internal colonial politics; those colonies acquired through global European conflicts reflected the mid-century rise of territoriality and British nationalism in British colonial discourse. Moreover, new seal art embraced the grand manner of the High Renaissance, focusing less on static renderings of reality than on ideal forms, nobility, and classical themes.Footnote 88 Indians shared space with Greco-Roman gods and goddesses or lost it to them. As a result of these changes in the meaning and manner of eighteenth-century seal design, only two of the new Atlantic colonies formed early in the rule of the Georges depicted an Indian. In each case, the image signified another shift in just claims to authority—in one case referring to Indians as equal trade partners with colonists within the imperial system, and in the other with the Indian as merely an abstract representation, in classical mode, of the colony itself. Within the round of seals for new colonies gained at the conclusion of the Seven Years’ War in 1763, the Indian disappeared—even as (and perhaps because) popular accounts of Indigenous North American peoples during the war focused on accurate and detailed descriptions of both allies and enemies in the struggle for global hegemony.Footnote 89

The first Hanoverian Indian appeared when the Treaty of Utrecht with France in 1713 landed the former colony of Nova Scotia unambiguously (as far as Europeans were concerned) in British hands. After fifteen years of inexplicable delay, the Lords Commissioners of Trade and Plantations proposed that a seal be made for the colony, and within eighteen months, the double-sided engraving was ready. The reverse of the 1730 seal was standard-issue royal arms. The obverse, however, was significant and original for several reasons. Deviating from the pattern of previous Indian seals, it depicts an encounter between a merchant (not monarch) and an Indian, both standing (figure 12). The merchant is appropriately dressed for the period, contrasting sharply with the depiction of an Indian who is (uncharacteristically for Nova Scotia) nearly naked. The Indian holds a fur of some kind, and a beaver pelt lies at his feet. In the background is a map of the coast of Nova Scotia, with a fishing vessel and net off its coast. The fur trade, balanced with the benefits of rich fishing grounds, are the primary benefits (to the crown and to Europeans) of this new territory—an impression confirmed by the motto Terrae Marisque Opes (The resources of land and sea).Footnote 90 The Indian stands as a symbol of those resources through trade (importantly, not tribute, which would be better signified by an Indian on his knees). This depiction of imperium, putting colonist and Indian literally on the same footing, was not an indication of their equal civic standing within the colony of Nova Scotia but rather the benefit of the imperial system writ large, in which the colonist would benefit from British rule. Unlike previous seals, this image signals a more abstract imperial system in which the monarch is not depicted, but prosperity and territory are. This seal also marks the last new depiction of the Indian, as such, in a British colonial seal before the American Revolution.

Figure 12 Obverse side of the Seal of Nova Scotia, George III (1767). (The original George II image, nearly identical, may be found in Swan, Canada: Symbols of Sovereignty, 127.) Source: photo from the author's private collection. Courtesy of the Royal Mint.

Three more colonies requiring new seals emerged between the Treaty of Utrecht and the Seven Years’ War. Driven by political turmoil and brutal wars with Amerindian nations, Carolina split into two colonies: North and South Carolina. Soon thereafter, Georgia formed as a utopian colony for debtors and religious minorities. The seals for these three new colonies drew upon the unique history of each, expressed with neoclassical themes in the grand manner: river gods marking geographic boundaries, woman/goddess representations of colonies being sexually dominated by the monarch, Lady Liberty bearing horns of plenty. These figures were thoroughly European, as were the stories they told.

The exception was Georgia. The colony began its life three years after the crown takeover of North and South Carolina, carved out of a portion of South Carolina and chartered to a board of trustees led by philanthropist and prison reformer James Oglethorpe. The original seal of the chartered colony drew classical and territorial idioms together in a seal depicting a silkworm on one side and Greco-Roman gods on the other.Footnote 91 Despite hopeful beginnings, however, the colonial government collapsed, and in 1752, Georgia's trustees relinquished their claim to the crown. A new seal of the Province of Georgia was struck two years later (figure 13). Engraved by John Pine, graver of the North and South Carolina seals and friend to William Hogarth, the image depicts an Indian woman on her knees offering a skein of silk to the monarch. That she is Indian is indicated by her crown of feathers, and in that regard the image reflects the tradition of late Stuart seals. But this image is a synthesis of the old Indian and the new high manner. (She is virtually identical to a female figure wearing a mural crown in the Seal of South Carolina, who symbolizes the City of Charleston.) The Indian princess represents the place more than a class of people.Footnote 92 Unlike previous images of Indians, however, this young woman wears a classical robe, which has fallen, conveniently, to her waist, exposing her breasts.

Figure 13 Obverse side of the Seals of the Royal Colonies of Georgia and South Carolina, for George II and George III respectively. Source: photos from the author's private collection. Courtesy of the Royal Mint.

The detail of exposed breasts is significant, because it does not serve merely as a marker of the figure's sex, as it does in the original seal of Carolina (figure 6) or in late Stuart seals of New York Virginia, and Jamaica (figures 9 to 11). As Beth Cohen has argued, divesting the female breast in classical Greek art had specific meanings, since women's clothes were not designed to fall off, nor was female nudity accepted in public. Two meanings in particular are relevant here: a symbol of defeat, suggesting a state of pre- or post-physical violence, and eroticism, including divine rape, in which the exposure of her breasts suggests the woman's eagerness. Depictions of Zeus and Danae were common examples.Footnote 93 This trope recurred in European Renaissance painting, including the rococo period of the early Hanoverians (consider Boucher's Rape of Europa, ca. 1732). So do other aspects of bodily depiction. A woman's head thrust back and tilted is suggestive of orgasm. As the late eighteenth-century painter Fuseli explained of body position and movement, “the forms of virtue are erect, the forms of pleasure undulate.”Footnote 94

The Indian princess of the Georgia seal undulates. Her body twists toward us to give a full view of her torso, her empty arm swinging backward in a gesture of openness while her kneeling legs are open to the viewer and not squared to the monarch. Her head is cast slightly backward. She is not erect or sturdy in her submission. Lest there be any mistake, however, the position of her hand, so close to the body of the monarch and just below the phallic hilt of his sword, suggests that she is grasping at his scrotum. His left hand—usually holding the orb of office—is empty and almost caresses her cheek. This Indian woman is not a symbol of a people and should not be read as a commentary on Indian sexuality. Instead, she is an allegory for a Euro-American colony supposedly eager for the intervention of royal authority—a salacious image, consistent with early eighteenth-century erotic literature like the Merryland books, which compared women's body parts to topographic features and sex acts to types of land use.Footnote 95 The female figure in the South Carolina seal is even more sexualized. By contrast, George III's seals of both Georgia and South Carolina downplay the undulating innuendo of his father's originals.

The remaining elements of the Georgia seal were consistent with those of its era. In the background, a ship sails near the coast, while trees on a hill suggest mulberry trees, elements highlighting the strategic and commercial significance of the colony as well as the continuing hopes for its future as a site of silk production. The significance of silk is also alluded to in the motto Hinc Laudem Sperate Coloni (Hence, hope for praise o [agricultural] colonists). The quote is a reference to Virgil's Georgics—a ubiquitous source of Hanoverian seal quotation—and refers to the economic difficulties of the colony and its supposed future in silk.Footnote 96 (A looser translation today might read, “Hang in there, silk farmers!”) The Indian woman and the substantive meaning of the seal are disconnected. She no longer indicates, as previous Indian representations had done for over a century, the positioning of Indigenous peoples in just claims of authority in dominium and imperium. Instead, she joins Indian depictions in European fine art: Europa's sister symbol for America—not a metonymy but an allegory, a longstanding trope in other forms of seventeenth and eighteenth-century depiction of Indians.Footnote 97 The legitimacy claim within the seal is of the monarch answering the colonist's call for his potent intervention—Zeus shining on Danae.

The resolution of the Seven Years’ War (1754–1763) added considerably to the British Empire's global reach, and soon new royal colonies in the Americas required new seals. Indians appeared in none of these, nor in any new seal thereafter. The seal of Grenada depicted enslaved African people operating a sugar mill. The seal of East Florida depicted a fortress on a hill overlooking the ocean with ships sailing. West Florida's seal included an uninhabited bluff with trees. In the seal of Quebec, King George pointed to a parchment map of his new territory.Footnote 98 Land still figured in three of these depictions, but its connection to the people who originally inhabited it did not. Indeed, the Indian as allegory declined by the end of the century in many forms of British art.Footnote 99

While there is no evidence directly accounting for Indians’ disappearance from new seals, the most likely reason is the most straightforward: they were no longer needed. In relation to the basic purpose of seals as being visual and physical technologies of legitimization, the positioning of Indians vis-à-vis their land was not necessary for the legitimacy claims of each of these new colonial projects. None of the old incarnations fit: Indians as recipients of civilization, as vassals, or as symbols of American colonists themselves. Although Indigenous nations played a central role in the North American theatre of the Seven Years’ War, the war's result added territory to the British Empire through treaty among European powers, requiring different kinds of legitimacy arguments reflecting new forms of territoriality. Great Britain acquired Florida from Spain in exchange for Cuba, and, with French acquisitions, divided it into two colonies. In the logic of the seals, East Florida had immediate strategic value as well as land for white settlement; West Florida primarily offered the latter. Grenada, acquired from France in the Treaty of Paris, required no further legitimization, and its seal, promising the riches of sugar production, made no pretense of legitimacy or even personhood for the enslaved people it depicted. The transformation of New France into the Province of Quebec was, similarly for the crown, a legal matter of inter-European global warfare that shifted claims to a vast swath of territory (see figure 14). The motto reads Extensae gaudent agnoscere metae (loosely: It spreads joy to acknowledge these new boundaries). The legitimacy of the claim of authority over the Province of Quebec may be found in a map drawn up in Paris, by European diplomats settling the global scope of their empires, as the sigillary George reminds us.

Figure 14 Obverse side of the George III Seal of the Province of Quebec. Author's private collection. Courtesy of the Royal Mint.