Introduction

Improving sexual autonomy among women comes with various benefits, including better sexual and reproductive health outcomes such as the prevention of sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections and family planning (Fadumo, Reference Fadumo2014; Seidu et al., Reference Seidu, Aboagye, Okyere, Agbemavi, Akpeke and Budu2021). Women, in particular, have been disproportionately affected by sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections, especially HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS, 2013), and this is as a result of low sexual autonomy resulting from gender inequalities (Seidu et al., Reference Seidu, Aboagye, Okyere, Agbemavi, Akpeke and Budu2021). Sexual autonomy among women is the control women have over their own lives and the extent to which they have an equal voice with their partners in matters affecting themselves (Seidu et al., Reference Seidu, Aboagye, Okyere, Agbemavi, Akpeke and Budu2021). The Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 5 focuses on women’s empowerment to advance their rights in reproductive health decision-making, attitudes and overall ability to negotiate for safer sex with their male partners (United Nations, 2015). Policymakers, especially those in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), are therefore beginning to pay particular attention to issues relating to women’s sexual autonomy, including their ability to ask their partner(s) to use condoms during sex (Chol et al., Reference Chol, Negin, Agho and Cumming2019).

In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) in particular, the normative societal organization is based on a patriarchal system where men exercise power over women. Various religious and cultural traditions and beliefs restrict sexual autonomy among women and place them in subordination to men (Chol et al., Reference Chol, Negin, Agho and Cumming2019). Contraceptive use remains low in SSA while it has risen to relatively high levels in many areas of Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean (Van Lith et al., Reference Van Lith, Yahner and Bakamjian2013).

Over the past few decades, birth spacing has been a commonly used concept in family planning programmes in SSA, and is often tied to a health rationale for contraception (Westoff & Koffman, Reference Westoff and Koffman2010). However, there has been less focus on the group of women in SSA who want to limit childbearing (Westoff & Koffman, Reference Westoff and Koffman2010). Data show that the proportion of women in SSA who want to limit rather than postpone childbearing is rising steadily (Westoff, Reference Westoff2012). Increasing the use of contraception among these women will reduce high-risk fertility behaviours such as high-parity births, thereby contributing to the reduction of maternal mortality in the region (Stover & Ross, Reference Stover and Ross2009).

In SSA, women’s ability to negotiate for safer sex has been associated with sexual and reproductive health outcomes since men are regarded as more powerful, and sometimes autocratic, when it comes to sexual decision-making (Saul et al., Reference Saul, Bachman, Allen, Toiv, Cooney and Beamon2018; Darteh, Reference Darteh2020). In addition, associations have been found between some socio-demographic, economic and cultural factors, such a place of residence, marital status, age and educational level, and women’s ability to negotiate for safer sex (Exavery et al., Reference Exavery, Kanté, Jackson, Noronha, Sikustahili and Tani2012; Darteh et al., Reference Darteh, Doku and Esia-Donkoh2014; Ameyaw et al., Reference Ameyaw, Appiah, Agbesi and Kannor2017).

Meeting women’s reproductive intentions in the context of informed choice enables them to have the number of children they desire, improves the health and well-being of both women and their families, and ultimately affects macro-level health and development indicators (Atake & Ali, Reference Atake and Ali2019). To the best of the authors’ knowledge, there is limited evidence regarding the prevalence of safer sex negotiation and the association between safer sex negotiation and parity among women in SSA. Therefore, this study examined this in SSA using data from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHSs). The findings of the study could help inform policy formulation in the sub-Saharan African countries to reduce high parity and its negative consequences, such as maternal mortality.

Methods

Data source and study design

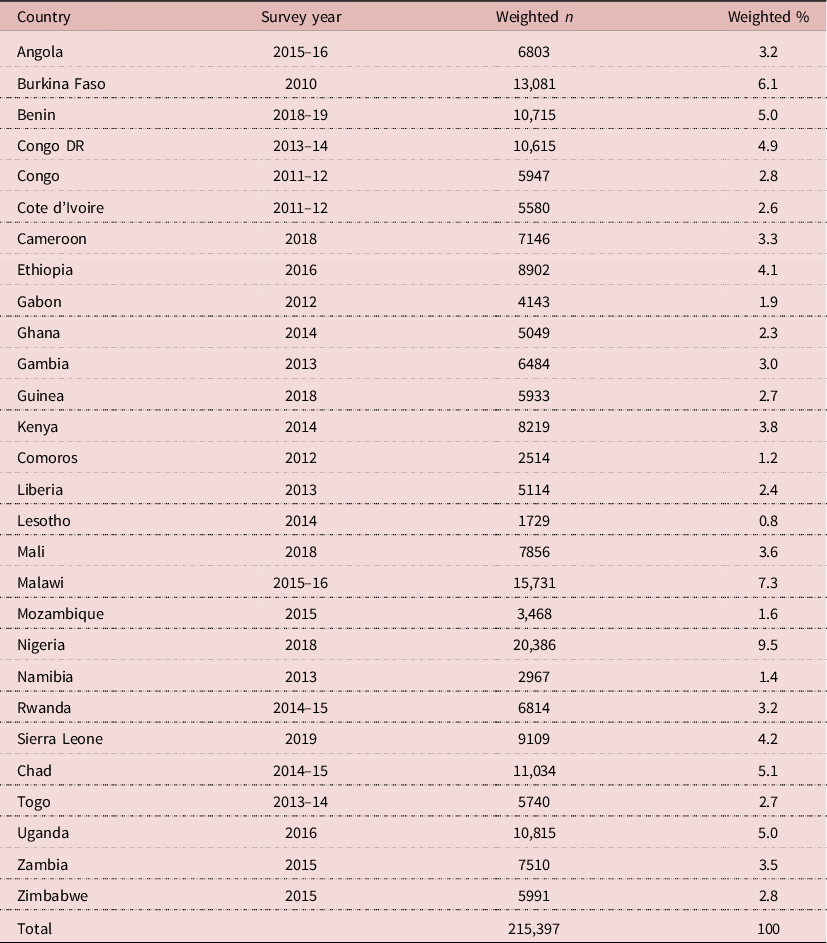

The study involved a cross-sectional analysis of DHS data from 28 sub-Saharan African countries. The DHS is a nationally representative study conducted globally in over 85 LMICs (Corsi et al., Reference Corsi, Neuman, Finlay and Subramanian2012). The survey uses a structured questionnaire to collect data on varied issues, including men’s health, maternal and child health, reproductive health, nutrition and substance use (Corsi et al., Reference Corsi, Neuman, Finlay and Subramanian2012). The survey utilized a two-stage cluster sampling technique. Details of the sampling process have been described in a previous study (Aliaga & Ruilin, Reference Aliaga and Ruilin2006). Data for the present study were extracted from the women’s file (individual recode) of the 28 DHSs. A total of 215,397 women aged 15–49 with complete cases on variables of interest were included in the study. The dataset is freely available for download at https://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines were followed when writing the manuscript (Von Elm et al., Reference Von Elm, Altman, Egger, Pocock, Gøtzsche and Vandenbroucke2007).

Study variables

Outcome variable

The outcome variable was parity. In the DHS, parity is defined as the number of live births of a woman. The responses were on a continuous scale of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 or more and varied from one survey to another. The responses were then first coded as ‘one’, ‘two’, ‘three’ and ‘four or more’. All women who reported having four or more births were considered to have ‘high parity’ (coded 1), while those reporting having one, two or three births were considered to have ‘low parity’ (coded 0). This has been adopted in several previous studies as a measure of high parity (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Hosen and Khan2019; Amir-ud-Din et al., Reference Amir-ud-Din, Naz, Rubi, Usman and Ghimire2021).

Independent variable

The independent variable was safer sex negotiation, created as an index variable from the two variables ‘can refuse sex’ and ‘can ask for condom use during sex’. For the first variable (can refuse sex), the respondents were asked ‘whether they can refuse sex with their partner’ and the question for the second variable (can ask for condom use) was ‘whether they can ask their partner to use a condom during sex’. The two variables had the same response options (1=no; 2=yes; and 3=don’t know/not sure/depends). In the present study, women whose response option was 3=don’t know/not sure/depends were excluded from the analysis. The variable ‘safer sex negotiation’ was created using the remaining two responses. Women who responded ‘yes’ for at least one of the two variables were said to have safer sex negotiations, and those that responded ‘no’ for both variables were categorized as not having safer sex negotiation. This categorization was informed by previous studies that used the DHS dataset (Darteh et al., Reference Darteh, Dickson and Doku2019; Tenkorang, Reference Tenkorang2012; Sano et al., Reference Sano, Antabe, Atuoye, Braimah, Galaa and Luginaah2018a; Putra et al., Reference Putra, Dendup and Januraga2020; Budu et al., Reference Budu, Ahinkorah, Seidu, Hagan, Agbemavi and Frimpong2021; Seidu et al., Reference Seidu, Aboagye, Okyere, Agbemavi, Akpeke and Budu2021).

Control variables

Eleven control variables were included in the analysis: individual-level factors (maternal age, maternal educational level, mass media exposure, contraceptive use, decision-making capacity, employment status, religion, and marital status) and household-level factors (wealth quintile, sex of household head, and place of residence). These control variables were selected based on their availability in the dataset and parsimony with safer sex negotiation from literature (Tenkorang, Reference Tenkorang2012; Atteraya et al., Reference Atteraya, Kimm and Song2014; Ung et al., Reference Ung, Boateng, Armah, Amoyaw, Luginaah and Kuuire2014; Sano et al., Reference Sano, Antabe, Atuoye, Braimah, Galaa and Luginaah2018a; Feyisetan & Oyediran, Reference Feyisetan and Oyediran2019; Putra et al., Reference Putra, Dendup and Januraga2020). Existing coding for maternal age, wealth quintile, sex of household head and place of residence found in the standard DHS was used. Women’s educational level was coded as no education, primary, secondary or higher. Marital status was re-coded as married or cohabiting. Religious affiliation was coded as Christianity, Islam and other. The coding of the rest of the control variables can be found in Table 2.

Statistical analyses

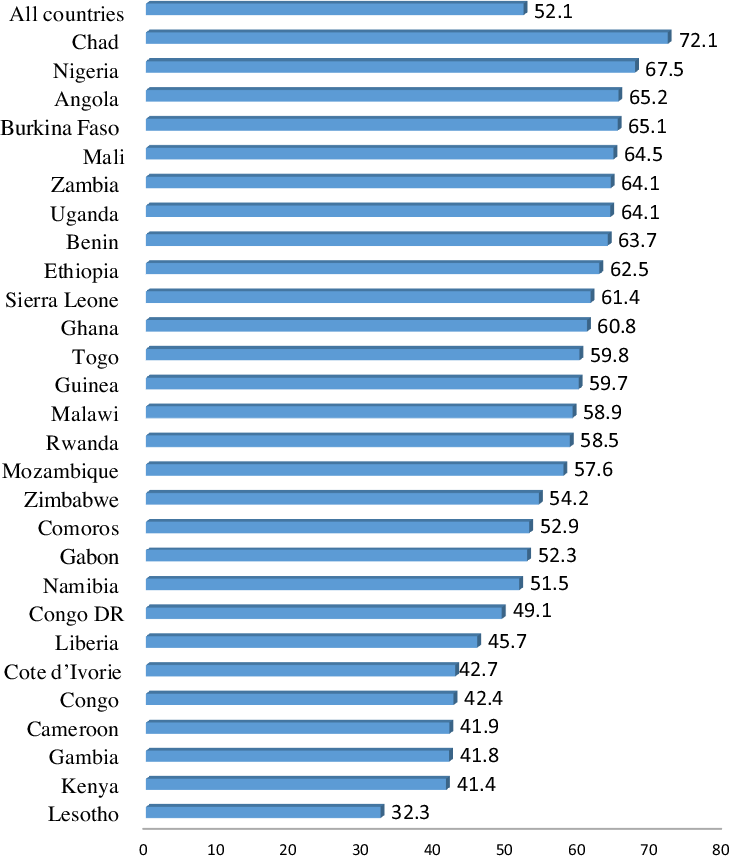

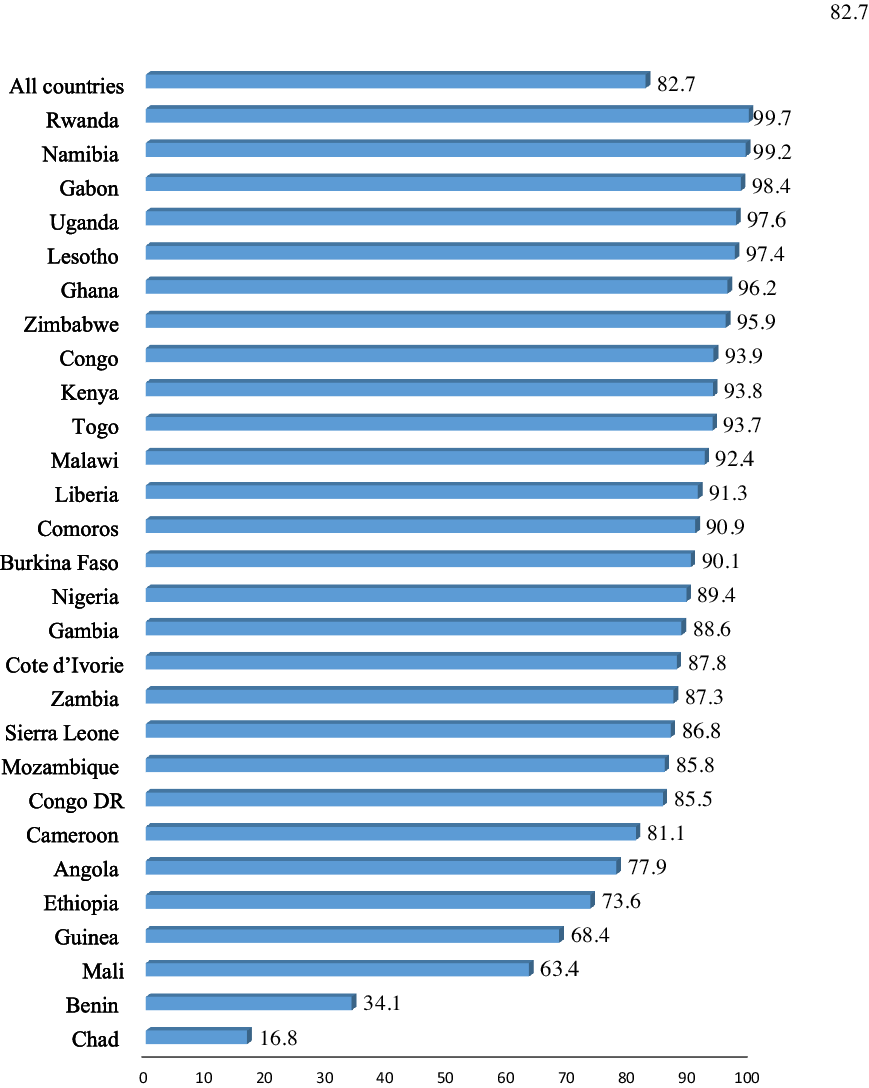

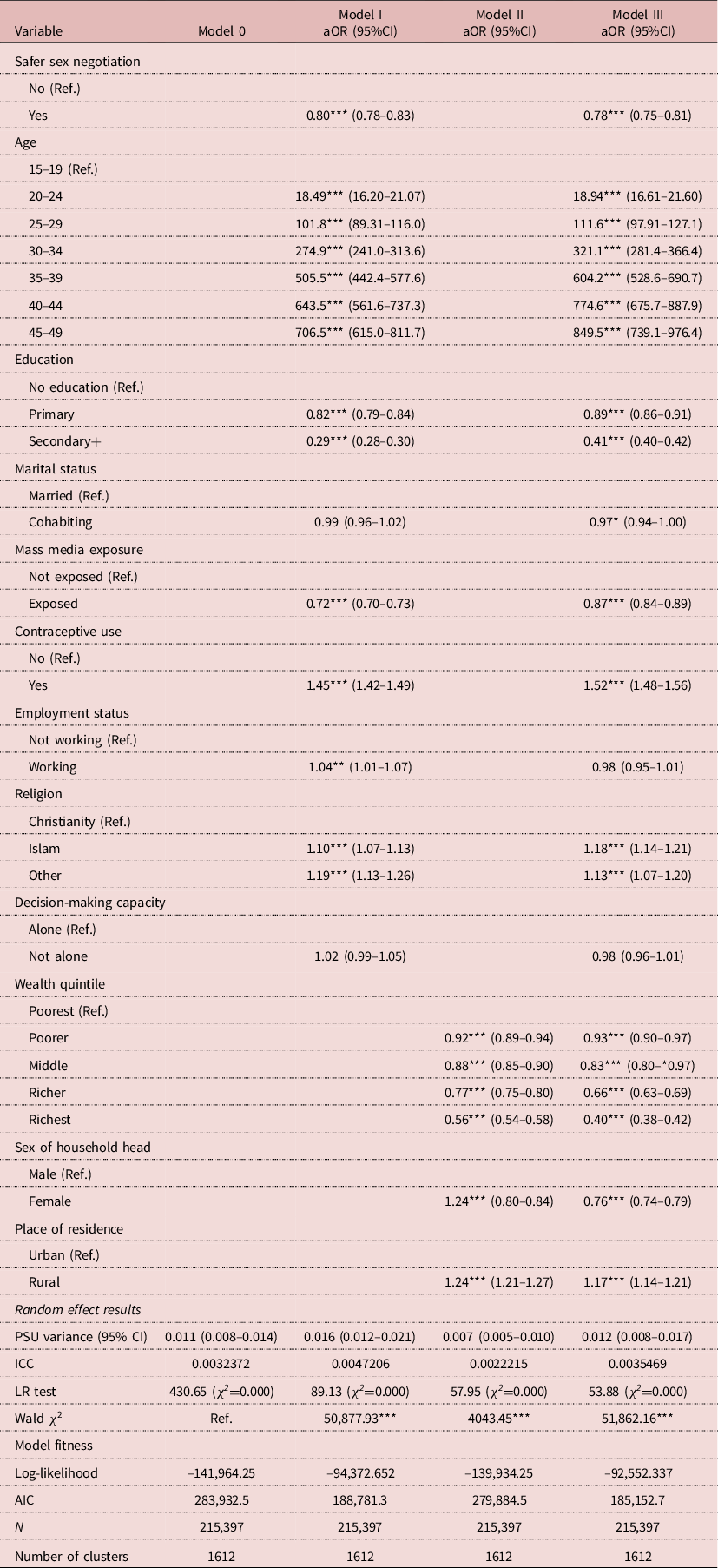

Data extraction, re-coding and final analyses were carried out using Stata version 16.0. Three levels of analyses were conducted. First, percentages were used to present the prevalences of high parity and safer sex negotiation (Figures 1 and 2, respectively). Secondly, Pearson’s chi-squared test was conducted to determine the distribution and relationship between high parity and safer sex negotiation (Table 2). Finally, multilevel logistic regression models were built to determine the association between safer sex negotiation and high parity among women in SSA. Model 0 showed the variance in high parity attributed to the clustering of the primary sampling units (PSUs) without the explanatory variables. Models I and II contained the individual- and household-level factors, respectively. The final model (Model III) had all the individual- and household-level factors. The Stata command melogit was used when fitting these models. Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) tests for model comparison were used (Table 3). The results of the regression analyses are presented in tabular form using adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with respective confidence intervals (CIs). Statistical significance was set at p<0.05 in the chi-squared and regression analyses. The women’s sample weights (v005/1,000,000) were applied to obtain unbiased estimates according to DHS guidelines and the survey command svy in Stata was used to adjust for the complex sampling structure of the data in the chi-squared and regression analyses.

Figure 1. Prevalence of high parity among women in sub-Saharan Africa.

Figure 2. Prevalence of safer sex negotiation among women in sub-Saharan Africa.

Table 1. Description of study sample of women aged 15–49, sub-Saharan Africa

Table 2. Distribution of high parity among women aged 15–49 by safer sex negotiation and other covariates in sub-Saharan Africa

Table 3. Factors associated with high parity among women aged 15–49 in sub-Saharan Africa

PSU Variance=primary sampling unit variance; ICC=intraclass correlation coefficient; LR test=likelihood ratio test; AIC=Akaike information criterion.

p<0.005**; p<0.01***; p<0.001.

Results

Prevalence of high parity and safer sex negotiation among women in sub-Saharan Africa

The overall prevalence of high parity in SSA was 52.1%, with in-country variations (Figure 1). Chad recorded the highest prevalence (72.1%) with Lesotho recording the lowest (32.3%). With regards to safer sex negotiation, a high prevalence of 82.7% was recorded in SSA, with the highest country-level prevalence found in Rwanda (99.7%) and the lowest observed in Chad (16.8%) Figure 2.

High parity was more prevalent among women aged 25 and above, those with no formal education (73.7%) or primary education (64.2%), those who were married (64.4%), those in the poorest wealth quintile (68.4%) and women who were residing in rural areas (66.3%) compared with women who were younger than 25 years, those with at least secondary education, those who were cohabiting, those in the richest wealth quintile and women residing in urban areas (Table 2).

Association between safer sex negotiation and high parity among women in sub-Saharan Africa

Table 3 shows the association between safer sex negotiation and high parity among women in SSA. Women who had the capacity to negotiate for safer sex were less likely to have high parity compared with those who had no capacity to negotiate for safer sex (aOR=0.78, CI: 0.75–0.81).

Discussion

This study sought to investigate the association between safer sex negotiation and high parity among women of reproductive age in SSA using data from the DHS of 28 countries. The prevalence of high parity among women in SSA was 52.1%, with Chad having the highest prevalence of 72.1% and Lesotho the lowest (32.3%). With regard to safer sex negotiation, the findings indicate a prevalence of 82.7% among women in SSA, with women in Rwanda (99.7%) and Chad (16.8%) having the highest and lowest prevalence rates, respectively. The findings also suggest an inverse relationship between women’s ability to negotiate for safer sex and high parity in SSA. Specifically, women who had increased ability to negotiate for safer sex had decreased odds for high parity, while those who had decreased ability to negotiate for safer sex had increased odds for high parity. Other factors that were associated with high parity were age, educational level, marital status, exposure to media, contraceptive use, religion, wealth quintile, sex of household head and place of residence.

The prevalence of high parity in SSA recorded in this study (52.1%) supports the findings of previous studies, which suggested that the majority of women in SSA have high parity, albeit with country-level differences (Van Lith et al., Reference Van Lith, Yahner and Bakamjian2013; Atake & Ali, Reference Atake and Ali2019; Vollset et al., Reference Vollset, Goren, Yuan, Cao, Smith, Hsiao and Murray2020). In spite of significant decline in the rate of population growth in SSA, the majority of women continue to have parity three or higher, largely due to low levels of educational attainment and contraceptive use and other socio-cultural factors (Yaya et al., Reference Yaya, Uthman, Ekholuenetale and Bishwajit2018; Vollset et al., Reference Vollset, Goren, Yuan, Cao, Smith, Hsiao and Murray2020). The prevalence of high parity was highest in Chad (72.1%) and lowest in Lesotho (32.3%). The high literacy rate and low contraceptive use in Chad relative to Lesotho (Yaya et al., Reference Yaya, Uthman, Ekholuenetale and Bishwajit2018) might have accounted for the greater prevalence of high parity in Chad. For example, recent estimates by UNESCO (2021) have revealed that 56.5% of the female population in Chad are illiterate as against 22.6% in Lesotho.

With regard to safer sex negotiation, 82.7% of the women surveyed had the capacity to negotiate for safer sex. Similar studies in SSA have reported a high prevalence of safer sex negotiation among women in SSA (Aboagye et al., Reference Aboagye, Ahinkorah, Seidu, Adu, Hagan, Amu and Yaya2021; Seidu et al., Reference Seidu, Aboagye, Okyere, Agbemavi, Akpeke and Budu2021). The increasing prevalence of safer sex negotiation among women in SSA could be due to factors such as improved access to education and mass media exposure (Aboagye et al., Reference Aboagye, Ahinkorah, Seidu, Adu, Hagan, Amu and Yaya2021; Seidu et al., Reference Seidu, Aboagye, Okyere, Agbemavi, Akpeke and Budu2021). Previous studies have reported that education and exposure to mass media are associated with increasing women’s empowerment and decision-making capacity, which influence their ability to negotiate for safer sex (De Coninck et al., Reference De Coninck, Feyissa, Ekström and Marrone2014; Seidu et al., Reference Seidu, Ahinkorah, Hagan, Ameyaw, Abodey and Odoi2020). As found in this study, education, mass media exposure, household wealth and sex of household are associated with women’s ability to negotiate for safer sex. Perhaps, varied levels of these factors in different countries in SSA could account for the different prevalence of safer sex negotiations among women in different countries in SSA. For instance, while 99.7% of women in Rwanda reported having the capacity to negotiate for safer sex, only 16.8% of the women in Chad did. The high literacy rate and media exposure in Rwanda relative to Chad might have contributed to the higher prevalence of safer sex negotiation in Rwanda compared with Chad (Aboagye et al., Reference Aboagye, Ahinkorah, Seidu, Adu, Hagan, Amu and Yaya2021).

Women’s capacity to negotiate the conditions and timing of sex is important in determining parity and other maternal health outcomes (Seidu et al., Reference Seidu, Aboagye, Okyere, Agbemavi, Akpeke and Budu2021). In this study, women who had increased ability to negotiate for safer sex had decreased odds of high parity and vice versa. This finding supports findings from previous studies in SSA (Seidu et al., Reference Seidu, Aboagye, Okyere, Agbemavi, Akpeke and Budu2021) and Nepal (Atteraya et al., Reference Atteraya, Kimm and Song2014). A plausible reason for this is the increased tendency for women with the ability to negotiate for safer sex, to refuse sex or to ask their partners to use condoms or other family planning methods during sex with the aim of avoiding unintended pregnancies or limit parity (Atteraya et al., Reference Atteraya, Kimm and Song2014). Also, women’s ability to negotiate for safer sex is a function of their autonomy regarding their participation in decision-making, including family size and birth spacing (Stanfors & Larsson, Reference Stanfors and Larsson2014; Ung et al., Reference Ung, Boateng, Armah, Amoyaw, Luginaah and Kuuire2014). Thus, women’s empowerment is a strategic approach to increasing their ability to negotiate for safer sex and limit their number of births (Seidu et al., Reference Seidu, Aboagye, Okyere, Agbemavi, Akpeke and Budu2021).

The present study showed that women with primary, secondary and higher education had lower odds of high parity compared with women with no education. Education can delay marriages and childbearing as well as improve women’s economic viability and hence reduce their risk of giving birth to many children (Stanfors & Larsson, Reference Stanfors and Larsson2014). Therefore, there is a need for concerted efforts and strategies to promote girl-child education since it appears to be one of the best approaches to limiting high parity, especially in countries with lower rates of educational attainment such as Chad.

Although the use of contraceptives is widely assumed to reduce the prevalence of high parity (Van Lith et al., Reference Van Lith, Yahner and Bakamjian2013; Yaya et al., Reference Yaya, Uthman, Ekholuenetale and Bishwajit2018), the findings of this study suggest that women who use contraceptives have higher odds of high parity compared with those who do not use contraceptives. This finding is supported by those of previous studies in Kenya (Ettarh & Kyobutungi, Reference Ettarh and Kyobutungi2012) and Ethiopia (Lakew et al., Reference Lakew, Reda, Tamene, Benedict and Deribe2013). Perhaps the majority of the women who use contraceptives in SSA might do so only after attaining high parity. Thus, contraceptives may be largely used by high-parity women who want to stop childbearing but not as a means of avoiding high parity (Lakew et al., Reference Lakew, Reda, Tamene, Benedict and Deribe2013). This could limit the benefits of contraceptives as a means of avoiding high parity among women in SSA. Therefore, considering the increased risk for maternal and child morbidity and mortality associated with high parity (Stover & Ross, Reference Stover and Ross2013; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Ahmed, Roche, Sonneveldt and Darmstadt2015; Abedin & Arunachalam, Reference Abedin and Arunachalam2020), it is important for policymakers not only to promote the use of contraceptives among women but also to ensure their appropriate use to prevent high parity.

The main strength of this study was the use of the most recent nationally representative DHS datasets of 28 sub-Saharan African countries. Apart from using well-trained enumerators in data collection, the appropriateness of the statistical tool used for the analysis, coupled with the probability method employed in selecting respondents, makes the findings of this study robust and generalizable to women of reproductive age in SSA. However, the findings only suggest an association between safer sex negotiation and parity and not causality, since the study relied on cross-sectional data. Also, both the ability to negotiate for safer sex and parity were self-reported and may have been affected by social desirability bias.

In conclusion, this study identified a significant association between safer sex negotiation and high parity among women of reproductive age in SSA. The findings suggest that women’s ability to negotiate for safer sex could reduce high parity among women in SSA. Therefore, policies and programmes aimed at birth control or reducing high parity among women could be targeted at improving their capacity to negotiate for safer sex. Such interventions could be targeted at empowering women and improving their decision-making capacity through education, access to mass media and employment. Such interventions could reduce high parity among women and improve maternal and child health outcomes in SSA.

Funding

The study received no funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was not required for this study since the DHS datasets are publicly available. The DHS reports showed that ethical clearances were obtained from the Ethics Committee of ORC Macro Inc., as well as the Ethics Boards of the partner organizations of the various countries, including the Ministries of Health. The survey was conducted with adherence to the standards for ensuring the protection of respondents’ privacy. ICF International ensures that the survey complies with the US Department of Health and Human Services’ regulations for the respect of human subjects. Further information about the DHS data usage and ethical standards is available at http://goo.gl/ny8T6X.