No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 16 January 2009

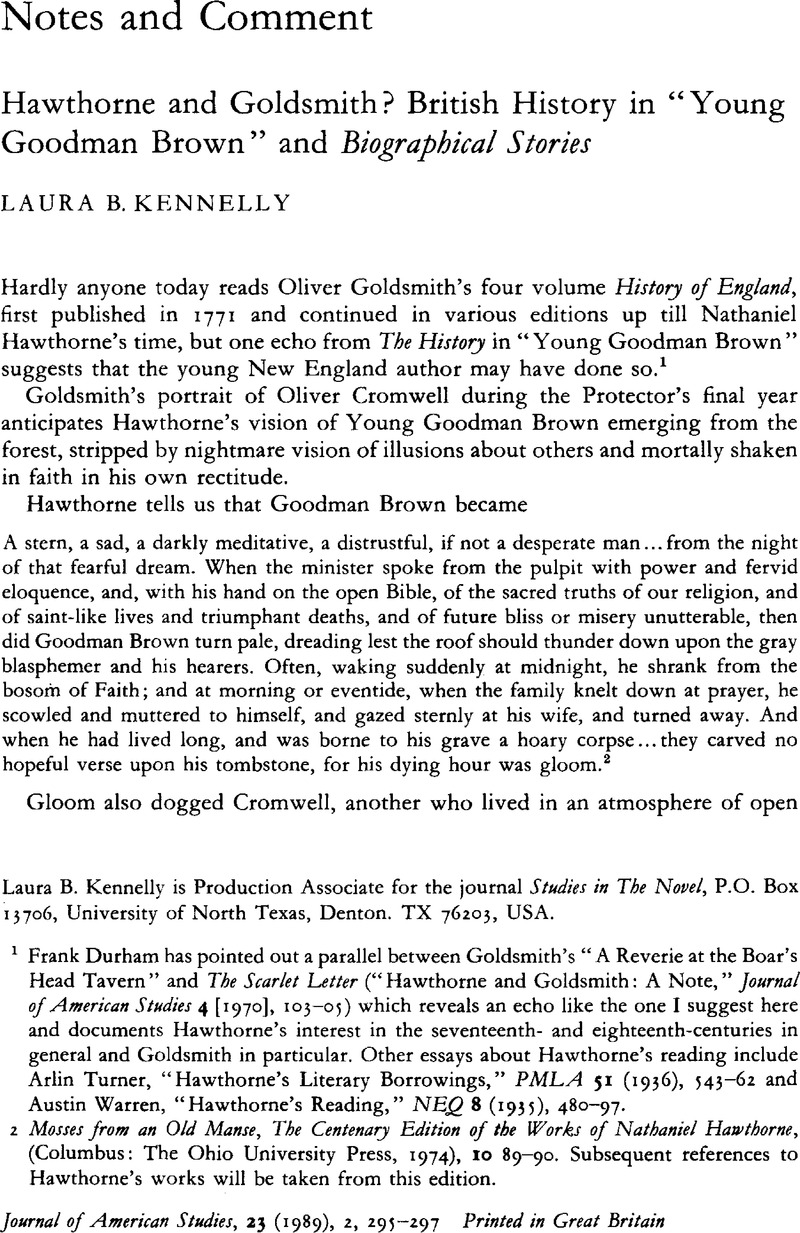

1 Frank Durham has pointed out a parallel between Goldsmith's “A Reverie at the Boar's Head Tavern” and The Scarlet Letter (“Hawthorne and Goldsmith: A Note,” Journal of American Studies 4 [1970], 103–05Google Scholar) which reveals an echo like the one I suggest here and documents Hawthorne's interest in the seventeenth- and eighteenth-centuries in general and Goldsmith in particular. Other essays about Hawthorne's reading include Turner, Arlin, “Hawthorne's Literary Borrowings,” PMLA 51 (1936), 543–62CrossRefGoogle Scholar and Warren, Austin, “Hawthorne's Reading,” NEQ 8 (1935), 480–97.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

2 Mosses from an Old Manse, The Centenary Edition of the Works of Nathaniel Havthorne, (Columbus: The Ohio University Press, 1974), 10 89–90.Google Scholar Subsequent references to Hawthorne's works will be taken from this edition.

3 The History of England from the Earliest Times to the Death of George II, Vol. 3 (London: Printed for T. Davies, 1771).Google Scholar Goldsmith drew most of his text from David Hume's The History of Great Britain, but his portrait of Cromwell varies significantly from Hume's.

4 True Stories From History and Biography, Vol. 6 of The Centenary Edition, 1972.Google Scholar

5 As, for example, in “The Ambitious Guest” when Hawthorne sets up likeable characters before he buries them in an avalanche.

6 Billman's, Carol “Nathaniel Hawthorne: ‘Revolutionizer’ of Children's Literature?” Studies in American Fiction 10 (Spring 1982), 107–14, documents didacticism in his children's stories.CrossRefGoogle Scholar