No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 16 January 2009

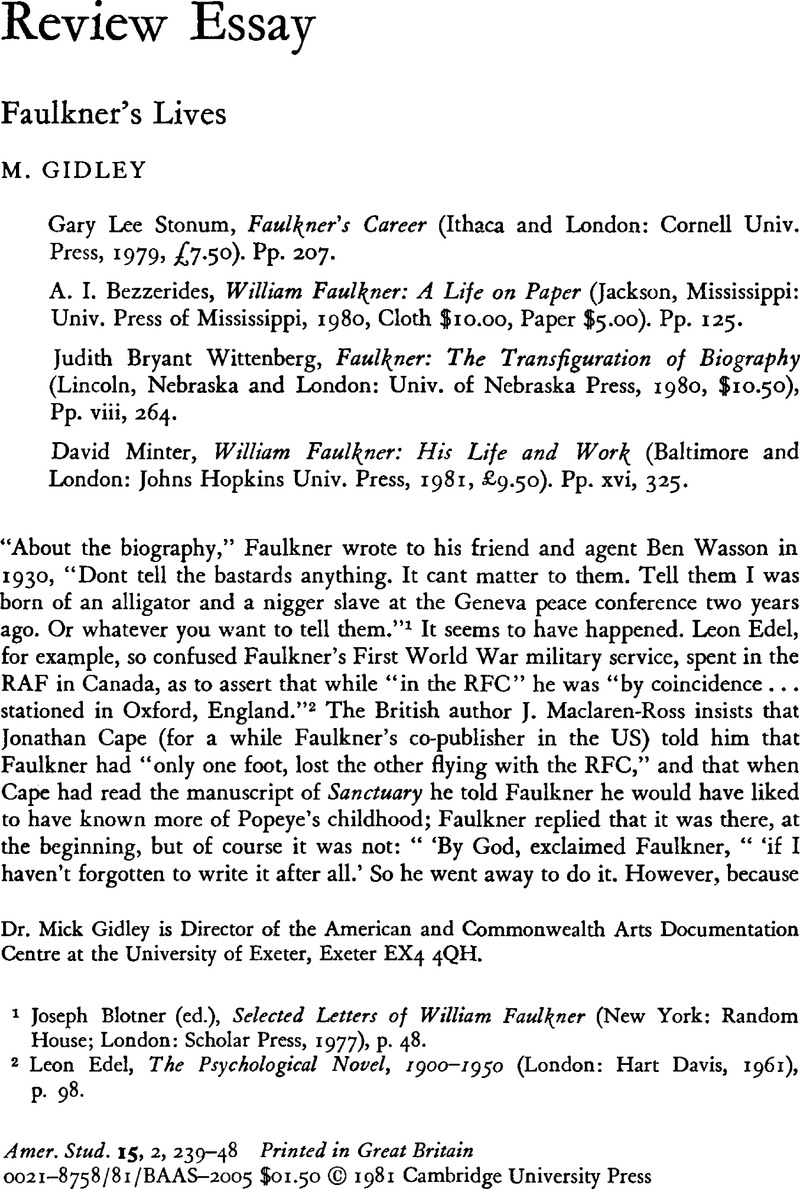

1 Blotner, Joseph (ed.), Selected Letters of William Faulkner (New York: Random House; London: Scholar Press, 1977), p. 48Google Scholar.

2 Edel, Leon, The Psychological Novel, 1900–1950 (London: Hart Davis, 1961), p. 98Google Scholar.

3 Maclaren-Ross, J., Memoirs of the Forties (London: Alan Ross, 1965), p. 10Google Scholar. Maclaren-Ross – who boasts of a “perfect memory” – also says that Cape told him that Faulkner had written Sanctuary (not As I Lay Dying) while working as a night watchman.

4 Weatherby, W. J., Breaking the Silence: The Negro Struggle in the USA (Harmondsworth: Penguin Original, 1965), p. 166Google Scholar. Weatherby also reveals Faulkner's friend Phil Stone as a markedly bigotted man (p. 167).

5 Illustration of painting titled “Red Leaves” in John Faulkner: Artist Author. Catalogue of an exhibition held at the Brooks Memorial Art Gallery, Memphis, 12–27 Oct. 1968.

6 Faulkner, John, My Brother Bill (New York: Trident, 1963; London: Gollancz, 1964), p. 268Google Scholar. Murry Falkner, Faulkner's other surviving brother, comes out no better if the same test is used, though in general his book, The Falkners of Mississippi: A Memoir (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State Univ. Press, 1967)Google Scholar, is more accurate. It is worth noting that in The Mansion (1959) (London: Chatto and Windus, 1961)Google Scholar Faulkner created a damning portrait of an agent of the organisation of which Murry was a dedicated employee, the FBI (see pp. 226–28). In his Old Times in the Faulkner Country, written with Watkins, Floyd B. (Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press, 1961)Google Scholar, John B. Cullen offers an interesting observation from his position on the periphery of Faulkner's Oxford circle: “Many people [in Oxford] believe that [his] writings and speeches on the race question are stronger and more liberal than his personal opinions” (p. 59). Faulkner himself discouraged the publication of Cullen's book – which is mostly interesting for its data on the local background to some of the fiction – by Random House; see his letter of Aug. 1959 to Erskine, Albert: Selected Letters, pp. 434–35Google Scholar.

7 Appendix to Webb, James W. and Green, A. Wigfall (eds.), William Faulkner of Oxford (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State Univ. Press, 1965)Google Scholar; incorporated, without acknowledgement, from Meriwether, James B. (ed.), “Early Notices of Faulkner by Phil Stone and Louis Cochran,” Mississippi Quarterly, 17 (Summer 1964), 136–64Google Scholar.

8 William Faulkner of Oxford, p. 228.

9 Millgate, Michael, The Achievement of William Faulkner (New York: Random House; London: Constable, 1966)Google Scholar; re-issued, with a new introduction by Millgate (Lincoln, Nebraska, and London: Univ. of Nebraska Press, 1978), pp. 1–57.

10 Lee Stonum, Gary, Faulkner's Career (Ithaca and London: Cornell Univ. Press, 1979)Google Scholar.

11 Ibid., p. 19.

12 For example, Zink, Karl, “Flux and Frozen Movement: The Imagery of Stasis in Faulkner's Prose,” PMLA, 71 (06 1956), 285–301CrossRefGoogle Scholar, and Adams, Richard P., Faulkner: Myth and Motion (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1968)Google Scholar.

13 Millgate, p. 179.

14 “On Privacy,” in Meriwether, James B. (ed.), Essays, Speeches and Public Letters (New York: Random House, 1965), pp. 62–75Google Scholar. Coughlan, , The Private World of William Faulkner (New York: Harpers, 1954)Google Scholar. Joseph Blotner has shown that Coughlan was not the stereotype of a sniffing reporter that Faulkner made of him; see Faulkner: A Biography (New York: Random House, 1974), 2, 1467–68Google Scholar and note page 192.

15 See the writings of Robert Cantwell, Malcolm Cowley and others annotated in the biography section of Meriwether, James B.'s commentary in Bryer, Jackson (ed.), Sixteen Modern American Authors (New York: Norton, 1973), pp. 229–31Google Scholar.

16 It is not surprising that some of the book's newspaper reviewers reported unfavourably on this score: for example, Lehmann-Haupt, Christopher, “A Huge Portrait in Hiccups,” New York Times, 27 02 1974Google Scholar, “Books of the Times” page. For the most rigorous critique of its scholarship, see the review-essay by Meriwether, James B., “Blotner's Faulkner,” Mississippi Quarterly, 28 (Summer 1975), 353–69Google Scholar.

17 Bezzerides, A. I., William Faulkner: A Life on Paper (Jackson, Mississippi: Univ. Press of Mississippi, 1980)Google Scholar.

18 Ibid., p. 53.

19 It is ironic that Meta Carpenter Wilde at one point chastises an unnamed Blotner for not identifying her in a photograph reproduced in his biography; see Wilde, and Borsten, Orin, A Loving Gentleman: The Love Story of William Faulkner and Meta Carpenter (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1976)Google Scholar, caption to a photograph between p. 96 and p. 97.

20 Ibid., p. 195.

21 Ibid., p. 127.

22 As W. H. Gass's review of Blotner's book pointed out, the life is “here” while the work is “there”; see “Mr. Blotner, Mr. Feaster and Mr. Faulkner,” New York Review of Books, 21, No. 11 (27 06 1974), 3–5Google Scholar.

23 Blotner, , Faulkner: A Biography, 2, 1204Google Scholar. This is also reported, slightly differently, in A Life on Paper, p. 92.

24 Blotner, , Faulkner: A Biography, 2, 1705Google Scholar.

25 Recently certain theoretical critics, notably James Olney, have re-interpreted the ideas, expressed earlier by Valéry and others, that virtually all writing may be seen as autobiography; see Olney, (ed.), Autobiography: Essays Theoretical and Critical (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1980)CrossRefGoogle Scholar. The books by Irwin, Wittenberg and Minter (reviewed in the present essay) may be seen as manifestations of this tendency.

26 Wittenberg, Judith Bryant, Faulkner: The Transfiguration of Biography (Lincoln, Nebraska and London: Univ. of Nebraska Press, 1980)Google Scholar.

27 Irwin, John T., Doubling and Incest/Repetition and Revenge: A Speculative Reading of Faulkner (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1975)Google Scholar.

28 See Kubie, Lawrence, “William Faulkner's Sanctuary: [An Analysis]” (1934) in Faulkner: A Collection of Critical Essays (ed.), Warren, Robert Penn (Engelwood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1965), pp. 137–46Google Scholar.

29 Wittenberg, p. 110.

30 Minter, David, William Faulkner: His Life and Work (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1981)Google Scholar.

31 Important sources additional to those already mentioned in this essay include much work with unpublished archival materials; a University of Mississippi master's thesis by Faulkner's niece, Dean Faulkner Wells, on her father, Dean Swift Faulkner (1975); and a memoir by his stepson, Franklin, Malcolm, called Bitterweeds (Irving, Texas: Society for the Study of Traditional Culture, 1977)Google Scholar.

32 To some extent, the concept of oscillation is related, in the history of Faulkner criticism, if not biography, to the oxymoronic pattern first described at length by Slatoff, Walter J. in Quest for Failure: A Study of William Faulkner (Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press, 1960)Google Scholar.

33 Building on the researches of Blotner, and McHaney, Thomas (especially in William Faulkner's “The Wild Palms”: A Study [Jackson, Mississippi: Univ Press of Mississippi, 1975])Google Scholar, Cleanth Brooks provides a complementary reading of the Baird, Helen relationship in “The Image of Helen Baird in Faulkner's Early Poetry and Fiction,” Sewanee Review, 85 (Spring 1977), 218–34Google Scholar.

34 Minter, p. 116.

35 Selected Letters, p. 20.