On 3 April 1818, around five o'clock in the morning, eighty armed men showed up at Jacob Faber's slave trading outpost in the Kerefe River in southern Sierra Leone. The intruders plundered the place and took Faber's firearms, food supplies, boats, and anything else of value. The compound was torn down, and Faber, an American citizen, was tied up by the ‘natives’, stripped of his clothes, taken across the river, and forced to walk barefoot for thirty miles among the mangroves ‘under the burning and searing Sunrays’. Faber spent the next days imprisoned, shackled, sleeping on a plank, and having ‘fetid fish’ for dinner. Weeks later, he managed to escape, get on a ship, and set sail to Cuba.Footnote 1

One year later, as he faced trial in Havana, Faber recounted his last days in Africa. He presented in court hundreds of documents produced during his stay in Galinhas between 1816 and 1819. These records, comprising personal letters, ledgers, ship accounts, and testimonies, are today located in the Cuban National Archive. These colonial sources constitute rare evidence of a slave trader's daily operations in precolonial Africa. Combined with archival records from Cuba, Sierra Leone, England, the United States, and Spain, they offer insights on the rise of Galinhas as the leading Atlantic slave market in nineteenth-century Upper Guinea as well as the warfare in the region that led to the foundation of the Galinhas kingdom (1808–20).

The first section of this article, Atlantic in perspective, explains the rise of Galinhas's slaving market due to the relocation of slave-trading actors, networks, and routes that unfolded across the North Atlantic in the aftermath of the Anglo-American abolition. Particular emphasis is placed upon the establishment of a transatlantic corridor between Cuba and Galinhas as a result of the relocation of American slave traders to Havana and southern Sierra Leone after 1808. The second section, grounded in Africa, comprises an account of the foundation of the Galinhas kingdom. I argue that the kingdom, one of the predatory states that arose during the slave trade era, consolidated its power through slave exports to Cuba and merchandise imports from Havana. I also suggest a new angle from which to look at the relationship between human trade, warfare, and politics. During the foundation of the Galinhas kingdom, wars, I argue, were detrimental to the slave trade.

Since W. E. B. Du Bois's iconic text on the US slave trade, historians have explored the strategies adopted by US merchants to continue trading Africans after 1808.Footnote 2 Yet they have overlooked a critical but unintended consequence of abolition: the simultaneous and interconnected rise of Cuba's slave-trading market and that of some regions in Upper Guinea such as Galinhas.Footnote 3 Historians have also examined the transatlantic symbiosis created between areas in the Americas and Africa.Footnote 4 However, until recently scholars have largely ignored the Spanish Empire's role and participation in this process.Footnote 5 While Sven Holsoe and Adam Jones, the leading experts on Galinhas, have pointed out the reinforcing correlation between the transatlantic slave trade and the rise of the kingdom, the substantive connection with Cuba has received little attention.Footnote 6

Historians have found that the transatlantic slave trade enabled or consolidated some precolonial African states.Footnote 7 In other cases, it eroded political centers of power or reinforced existing political decentralization.Footnote 8 Galinhas fits the first category. It grew to become a predatory state whose primary revenue source was the Atlantic slave trade, a prime example of a state reproducing itself through the traffic. Cuba's resources, such as firearms, luxury items, and other subsistence goods, were crucial for consolidating and expanding Siaka's material and symbolic power. Thus, Galinhas conforms to the broader pattern identified in other precolonial African political entities as the ‘war-slave-gun cycle’, illustrated in detail by Richard Roberts in the case of the Bambara kingdom of Segu and debated by other historians.Footnote 9 Galinhas was the archetypical case of a dependent economy based on the production of a single commodity — in this case, people. Like any other dependent economy, lacking the demographic and environmental conditions to diversify and adapt to so-called ‘legitimate commerce’, the kingdom collapsed when the slave trade ended.

As in every predatory state based on the production of slaves for the Atlantic market, warfare was fundamental for the Galinhas kingdom. Nonetheless, the benefits to the slave trade derived from warfare are less evident if we focus, as this article does, on the dynamic foundational moment of the kingdom. For its consolidation, prosperity, and stability, the Galinhas kingdom came to depend on a ‘slaving frontier’ inland and further from coastal markets.Footnote 10 During the wars, before the kingdom's foundation, that slaving frontier did not exist. War and trade coexisted in the same space, which brought counterproductive results. As recognized by Claude Meillassoux, war became detrimental when its complementary function to trade became unbalanced.Footnote 11 Indeed, warfare continued producing captives, but since society's fabric unraveled, every other social activity underpinning the slave trade was disrupted. Faber's records and other contemporary evidence reveals this tension.

THE RISE OF GALINHAS: THE ANGLO-AMERICAN ABOLITION, THE UNITED STATES, AND CUBA

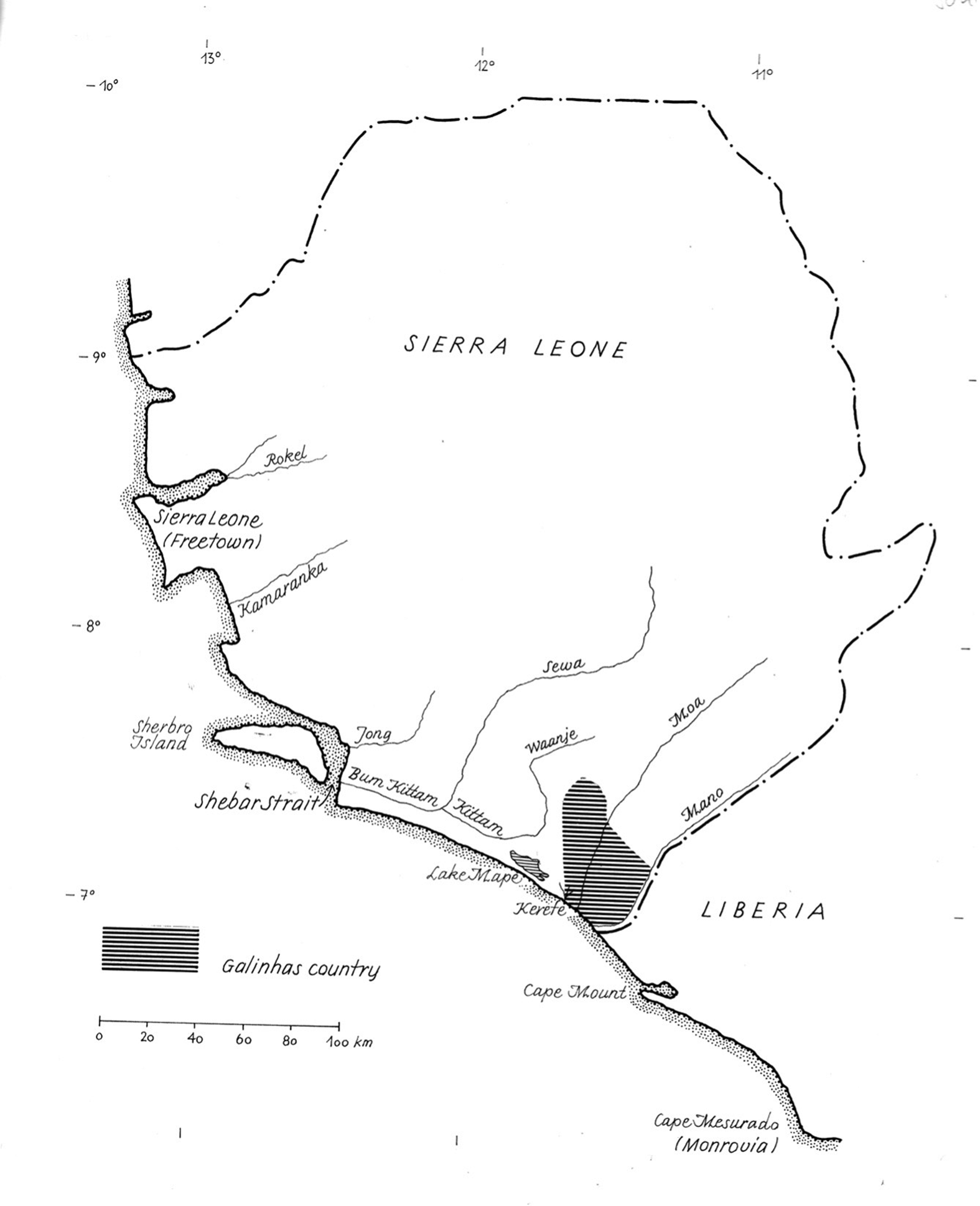

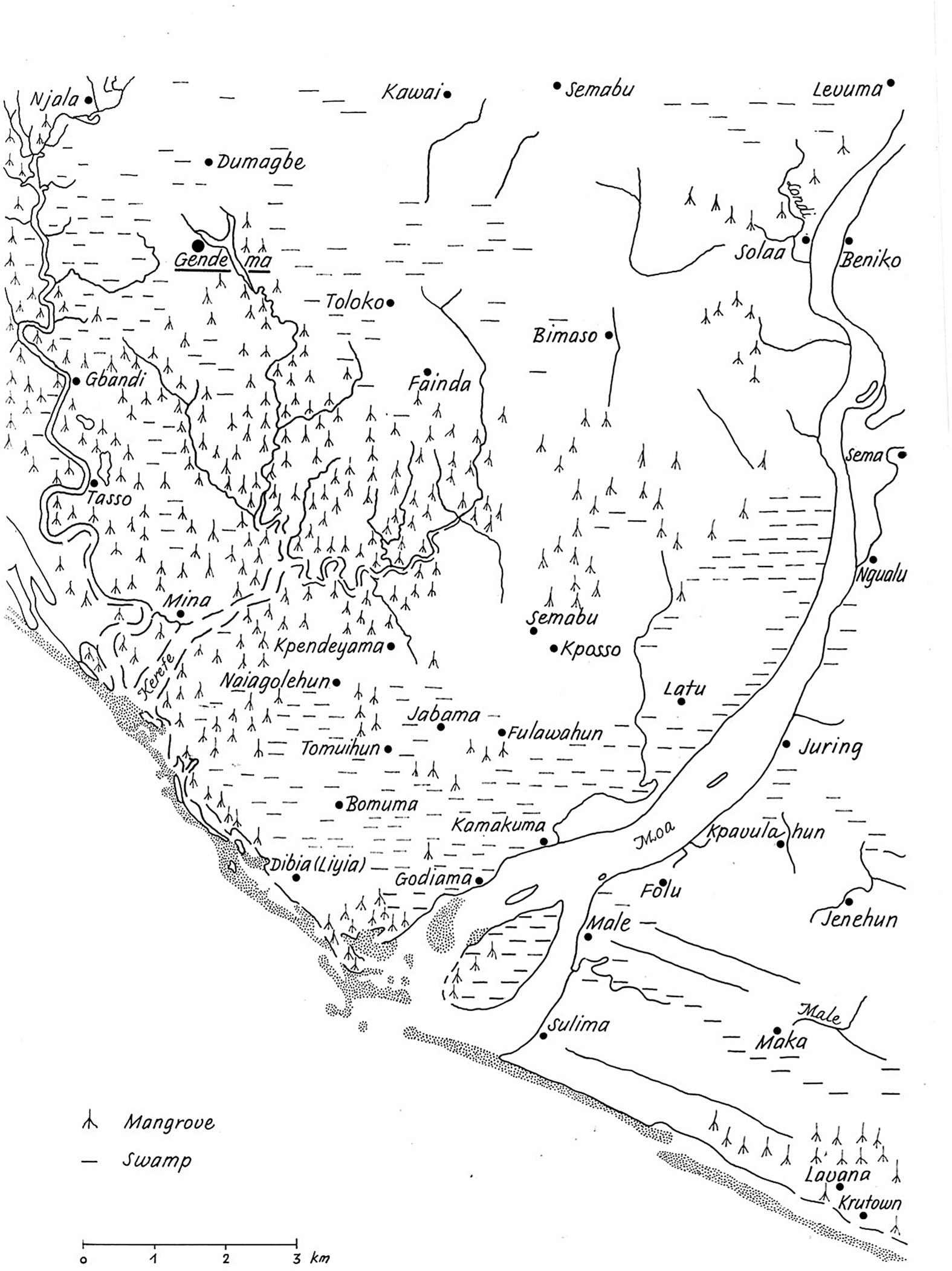

Since its first mention in 1485 by the cartographer Pedro Reinel, Europeans have used the term Galinhas (meaning chickens in Portuguese) to refer to various lands and rivers on the southernmost coast of present-day Sierra Leone (Fig. 1).Footnote 12 In its broader definition, Galinhas encompassed the coastal region between the Kerefe and Mano Rivers.Footnote 13 The term also referred to the rivers’ estuaries, which converged on the Atlantic, forming an interconnected system of lagoons and waterways. For most of the nineteenth century, Galinhas meant the Kerefe River in particular.Footnote 14 However, the inhabitants used the Mande term dsáia (mangrove country) due to the predominant coastal vegetation (Fig. 2).Footnote 15 Galinhas incorporated the present-day chiefdoms of Galliness-Perri or Peri-Massaquoi, Kpaka, and Soro-Gbema in the district of Pujehun on the Liberian border.

Figure 1. The Republic of Sierra Leone and Galinhas.

Source: A. Jones, Slaves to Palm Kernels, 1. Reproduced by permission.

Figure 2. The Galinhas country.

Source: A. Jones, Slaves to Palm Kernels, 3. Reproduced by permission.

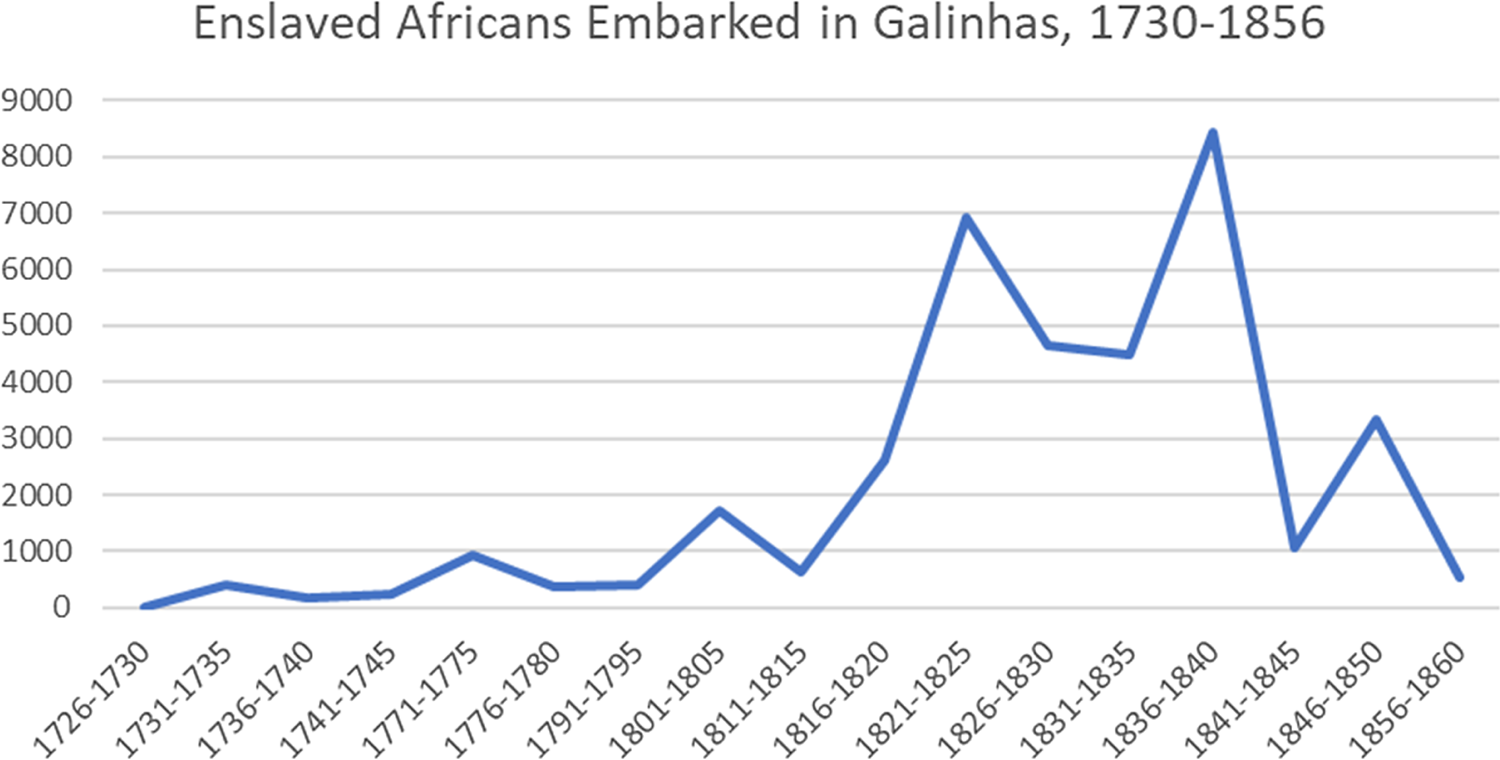

Environmental circumstances, low population, and poor slaving markets ensured that the Atlantic slave trade was not commercially significant until the late eighteenth century. Furthermore, it was not until after 1808 that it took center stage (Fig. 3).Footnote 16 Historian Adam Jones wrote that ‘the circumstances which attracted slave dealers to Galinhas at the end of the eighteenth century are likely to remain a mystery.’Footnote 17 However, if we zoom out from local to global events, the mystery fades. As a slave-trading region, Galinhas emerged at the point of coalescence of events in Europe, America, and Africa — from the conjunction of intertwined Atlantic and local processes.

Figure 3. Slave trade in Galinhas, 1730–1856.

Source: STDB, (https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyages/O7UPnaum), accessed 7 Oct. 2020.

By the mid-eighteenth century, the British intensified their slaving operations along the African coast as they searched for more forced labor for their West Indian colonies. Slave markets spread out from long-established depots such as Bunce Island, Sherbro, and Cape Mount to marginal regions such as Rio Pongo and Galinhas.Footnote 18 Yet it was not until the last decade of that century that British traders settled in more significant numbers in the region.Footnote 19 The further expansion of the transatlantic slave trade in the 1790s attracted British traders to Galinhas, including William Crundell, John Lascelles, John McQueen, Lancelot Bellerby, and Robert Bostock.Footnote 20 They cleared the path for the arrival of US slavers in the early nineteenth century.

After the American Revolution, US merchants rebuilt their national branch of the transatlantic slave trade. Following their British forefathers, they established trading partnerships along the African coast, including at Galinhas. One early example are the D'Wolfs, the most prolific slave-trading family in US history. They sent at least six ships to Galinhas between 1804 and 1808.Footnote 21 Increasing US legal restrictions on the trade meant that not every American ship returned to the United States. Three of them, Nancy (1804), Hiram (1805), and Charlotte (1805), unloaded their human cargo in Havana. They were not exceptional but were examples of the growing US involvement in the Cuban slave trade, which ultimately led to the Spanish/Cuban presence in Galinhas.Footnote 22

In 1789, Spain had deregulated the slave trade, and slave ships from all over the Atlantic world came to Cuba, with the British and Americans leading the list.Footnote 23 The opening responded to the expansion of Cuba's sugar production, which was further favored with the demise of Saint-Domingue after 1791. During the European and Napoleonic Wars (1792–1815), the neutral status of the US facilitated American dominance in the Cuban slave trade. American slavers occupied the vacuum left by the European competitors during the Franco-Spanish (1793–5) and Anglo-Spanish Wars (1796–1802, 1804–8). The 1803 reopening of the slave trade in Charleston boosted the US role as the leading supplier of captives to Cuba. In 1807 alone, of the 5,400 slaves that disembarked in Cuba, 80 per cent came from Charleston.Footnote 24 In fact, ‘Cuba received almost as many slaves from US vessels as did Charleston before 1820.’Footnote 25 With this high presence of US slave traders in Cuba, it is not surprising that American ships from Galinhas ended up in Havana. A new transatlantic slave trading corridor had emerged.

The British and American ban on the transatlantic slave trade sealed the intertwined Cuban-Galinhas slave-trading fate. The abolition prompted a relocation of slave-trading actors, networks, and routes in the North Atlantic. Within the Americas, many US slave traders transferred their operations to Havana, a familiar city where they had numerous trading networks. Others relocated to Galinhas, where they also had British connections. During the following years, they conducted trade between both Atlantic regions. One typical example was the American Charles Mason, a D'Wolf agent who joined the British merchants Robert Bostock and William Crundell in Galinhas and eventually relocated to Cuba.Footnote 26

The abolition also prompted relocations within Africa. In 1808 the British government turned the abolitionist settlement of Freetown, one hundred miles north of Galinhas, into a colony complete with a Vice-Admiralty Court and two Royal Navy vessels to enforce abolition.Footnote 27 These abolitionist initiatives drove slave traders to move to regions still free of trading restrictions, such as Rio Pongo and Galinhas, north and south of Freetown, respectively. Thus, Galinhas received from different sources more settlers, trade, and slave ships. In sum, Cuba and Galinhas concurrently welcomed those interested in continuing trading slaves in defiance of their nation's laws. For half a century, both regions shared a common interest in the human trade.

A grounded example of how the post-1808 relocation enabled the new transatlantic slave-trading route is the trajectory of US captain William Richmond. For years, Richmond commanded D'Wolf slave ships between Bristol-Charleston-Upper Guinea-Havana. His brig Jane, fitted in Bristol by James DeWolf, disembarked slaves in Havana in 1806 and Charleston in 1807.Footnote 28 After the U.S. Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves, Richmond set sail to Cuba to acquire Spanish papers, which permitted him to trade slaves ‘legally’. He transferred his schooner Dos Amigos nominally to a Spanish merchant and installed a Spanish captain on board to go to Galinhas.Footnote 29 The British were aware of the strategy commonly used by US citizens to circumvent the law:

[The Spanish flag] covers not only Americans but also, there are many reasons to believe, a considerable number of vessels actually British property. The American master and crew generally continue on board after the formal transfer, and two foreigners, under the denomination of captain and supercargo, are added to the ship. . . . The object of these Spanish Americans is to fill Cuba, Florida, Louisiana, and the Southern deserts of North America with slaves.Footnote 30

President James Madison himself admitted to Congress ‘that American citizens [we]re instrumental in carrying on a traffic in enslaved Africans, equally in violation of the laws of humanity, and defiance of those of their own country’.Footnote 31 The dozens of slave ships captured by British vessels in the Caribbean or off the African coast between 1808 and 1815 indicate a high ratio of ‘Spanish’ ships with thinly-veiled American ownership.

On 7 November 1810, HMS Crocodile intercepted Richmond's vessel Dos Amigos as it was approaching Galinhas. Since it did not have slaves aboard and was under the Spanish flag, the British released the vessel.Footnote 32 In Galinhas, Mason and Bostock loaded the ship with 328 slaves.Footnote 33 On 11 March 1811, the Dos Amigos weighed anchor in Havana with 295 African survivors and a single passenger.Footnote 34 Charles Mason had relocated to Cuba to serve as the agent in Havana of his Galinhas partners. One week later, when the Dos Amigos sailed again to Africa, it probably carried some letters from Mason to Bostock reporting the safe arrival and the profits made from the cargo's sale.Footnote 35 Between Mason's move to Havana in 1811 and his return to Africa in 1815, several Cuban-based but American-owned voyages went to Galinhas.

Since the British seized three of them, their documents, currently in Cuban, Spanish, and British archives, shed light on Americans’ role in creating the trading circuit Havana-Galinhas. In June 1811, the British captured the schooner Paloma off of Galinhas. The vessel, the Vice-Admiralty Court found, had been built in the United States, had been nominally sold in Havana to Cuban merchants, and had sailed from Havana to Norfolk, Virginia, to load merchandise.Footnote 36 In 1813, the bilander Juan was seized before reaching its destination. Prosecutors discovered that James White, a native from Germantown, New Jersey, who had lived in Charleston for the past seven years, co-owned the vessel along with Cuban-based Luis Martínez and Cornelio Souchay.Footnote 37 Freetown's court condemned the ship for ‘being the property of an American enemy’ and ‘trading in the universally illicit, illegal, and inhumane traffic in slaves’, a legal position based more on a humanitarian idealism than reality.Footnote 38 Finally, the schooner Maria Josefa had undertaken six voyages to Africa, three of them to Galinhas, between 1811 and 1814.Footnote 39 For what would be its final expedition, the British found that the nominal Cuban owner of the vessel, José García Álvarez, was working on behalf of an American as well.Footnote 40

The British not only captured ships but also raided slave-trading outposts from Rio Nunez to Cape Mesurado. In 1813, Freetown's Governor Charles Maxwell sent an armed force to destroy the settlements of Robert Bostock and John MacQueen in Cape Mesurado. Both were captured and transported to Australia.Footnote 41 After discovering his partners’ fate, Charles Mason purchased the former US privateer Commodore Perry, acquired Spanish papers, and renamed it the Rosa.Footnote 42 On 13 November 1815, the Rosa left Havana loaded with rum, tobacco, and gunpowder and captained by the experienced Bartolomé Marcelino Mestre.Footnote 43 The alleged owner of the Rosa was José García Álvarez, the same man that the year before had served as nominal owner of the schooner María Josefa.Footnote 44

The following June, HMS Mary spotted the Rosa in Galinhas, and after ‘an active fire between both parties’, the ship was captured and carried to Freetown.Footnote 45 On the grounds of using faux Spanish papers to disguise American ownership, the Vice-Admiralty Court condemned the Rosa.Footnote 46 Mason found himself stranded in Freetown and surrounded by dozens of sailors and captains from other ‘Spanish’ ships adjudicated by the British.Footnote 47 The shipless men managed to get a small vessel, the Bella Maria, to sail them to Cuba. Near the Bahamas, they were shipwrecked, and Charles Mason was one of the 21 men who perished.Footnote 48

The American merchant Jacob Faber replaced Mason in Galinhas. A native of Baltimore, Faber had been conducting business in Cuba since before 1808. After US abolition, he relocated to Rio Pongo, in the present-day Republic of Guinea, which had also become a hub for American slave merchants.Footnote 49 Like Galinhas, Rio Pongo was part of the broader trend of new transatlantic regions that expanded the trade and connected with Cuba after the abolition. Americans like Faber played a pivotal role in linking that African region with the Cuban slave market. For seven years, Jacob Faber sent loaded vessels from Pongo to Havana. In 1814, after the British burned down his factory, Faber returned to Cuba.Footnote 50

In 1816, six of Havana's merchants — the brothers José Ricardo, Juan, and Antonio O'Farrill, Juan Espinosa, Martín Zavala, and Cornelio Souchay — asked Faber to join a slave-trading venture. These men were part of a growing Cuban-based transatlantic slave-trading corridor with Upper Guinea. The German Huguenot Souchay, for example, had lived in Baltimore, knew Mason, and had already sent ships to Galinhas, such as Juan, in 1813. The six men planned to install Faber in Galinhas to establish a trading outpost. They would finance the enterprise, purchase a vessel in the United States, and supply everything Faber needed to start up the factory. The contract, signed on 10 April 1816, stipulated that they would provide merchandise and a fleet of six ships to conduct the slave trade between Galinhas and Havana. Faber would be responsible for managing the factory, gathering the captives, loading the vessels, and sending them to Cuba. In return, he would receive a quarter of the profits.Footnote 51 Galinhas was the first African slave-trading factory financed from Havana.Footnote 52

From the seventeenth to the early nineteenth century, the transportation of Africans to the Spanish Americas had been in Portuguese, Dutch, French, and British hands. Thus, by the time Madrid deregulated the slave trade in 1789, Spaniards did not possess trading outposts in Africa, networks, a slave-trading fleet, or any experience in the transatlantic human trade. Eager to tap into that commerce to more effectively supply the expanding plantation economy, Cuban-based traders took advantage of the presence of ‘foreign’ slave traders on the island. With American assistance, Cubans acquired ships, learned about the trade, trained captains and pilots, acquired commercial connections along the Upper Guinea coast, and established factories such as the one at Galinhas. Faber's trajectory embodies the transfer of technologies, expertise, and networks that enabled the creation of the Cuban-based transatlantic slave trade.

Faber's first stop was Baltimore. There, he acquired the schooner Iris, a former US privateer with ports for eighteen guns described as ‘an excellent ship for the type of voyage it will be employed’.Footnote 53 On 28 May 1816, the Iris arrived in Charleston captained by William Murphy, who was accompanied by Faber and Stephen Goss, the latter a slaver from Liverpool who had lived for nearly ten years in Galinhas and was transferring his factory to Faber.Footnote 54 The Iris was loaded with everything needed for an extended stay in Africa. Letters sent by Faber from Charleston to his partners in Havana listed the price, quantity, and descriptions of the merchandise and the suppliers’ names in Boston, New York, and Charleston. The list included a variety of dry food, alcoholic beverages, tobacco, coffee, cookware, furniture, fabrics, firearms, ammunition, carpentry tools, medicines, candles, construction materials, tableware, and much more.Footnote 55

By the time Faber sailed to Africa on 3 July 1816, a new trading system was in place. In violation of their country's laws, American merchants took over and expanded the trade from Galinhas to the Americas, particularly Cuba. After the end of the Napoleonic wars in 1815, the transatlantic slave trade peaked on the island as Cuban-based merchants consolidated their foothold in Galinhas. The redeployment of slave-trading actors, networks, and routes in the North Atlantic, the simultaneous relocation of US slave traders to Cuba and Galinhas, the shutting of long-established trading centers and the opening of new ones in Upper Guinea, the growth of Cuba as a slaving market and outfitting region, and the creation of a transatlantic corridor between Havana and Galinhas would shape the sociopolitical landscape of southern Sierra Leone for the next half-century. The consequences within Galinhas were immediate.

WARFARE, THE SLAVE TRADE, AND THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE GALINHAS KINGDOM

Galinhas's early-nineteenth-century social composition is critical to understanding the nature of the events that unfolded in the region. After the sixteenth-century disintegration of the Mali Empire, Mande-speaking people from the Upper Niger moved to the coast of present-day Sierra Leone and Liberia, where they conquered, partially assimilated, and intermarried with the Mel-speaking inhabitants of the coast, such as the Bullom, Krim, Gola, and Kissi.Footnote 56 The newcomers, the Mande-speaking Vai people, grew to become the most influential people at the coast and the leading slave traders in coastal Galinhas.Footnote 57 By the early nineteenth century, the Vai were surrounded by the Mende to the north, the Bullom and Krim to the northwest, and the Gola to the northeast.

The descendants of unions between European settlers and African women added another critical social component to Galinhas. As was customary in the relationship between landlords and strangers in West Africa, white merchants, to be granted access to the land and become part of the community, established kinship ties by marrying women related to the ruling elite. Those unions resulted in a progeny of people labeled by historians as ‘mulattos’, ‘Eurafricans’, or ‘lançados’, who achieved power as cultural and commercial middlemen or brokers between European merchants and African rulers.Footnote 58 The oldest Eurafrican lineages in Galinhas were the Clevelands, Gomezes, Rogerses, Caulkers, and Tuckers.Footnote 59

Vai peoples’ central political units were nucleated villages made up of extended family or members of the same clan or descent group. Each village had big men, called kpakoisia in Mende.Footnote 60 Individuals reached these positions of power through kinship ties, conquest in wars, and trading connections.Footnote 61 The community measured their leaders’ prestige and authority by the wealth they accumulated in the form of dependents, such as wives, offspring, or slaves, as well as the control they exerted over other territories. Demographic pressures, economic and trading growth, the threat of common enemies, military expansions, and family unions often brought clusters of villages together, forming more complex political systems that could be better described as confederations. European sources labeled the heads of those confederations of villages or chiefdoms as ‘kings’, and indeed, many Vai chiefs appropriated this term to negotiate with the white newcomers. However, among themselves, the Mende word mahawai or ‘big chief’ was used.Footnote 62 Patrilineal kinships and a narrative of common ancestry and history bound those larger chieftaincies.Footnote 63 According to a report submitted to Zachary Macaulay by a British slave trader who lived in Galinhas in the late 1790s,

[Galinhas] is divided into a great many towns or districts, each of which has a voice by a delegate in a congress which assembles for the purpose of regulating the affairs of the kingdom. These also elect a King who becomes their organ & who is invested with unlimited power to execute their resolves, but he cannot go beyond these. It is now seven years since the death of their last king & during that time the king's gold-headed cane has occupied his place at palavers, & to that the same respect is paid as to the king himself, his minister now as in his lifetime declaring & executing what he is instructed by the congress or palaver to consider as the king's will.Footnote 64

The growing early-nineteenth-century Atlantic slave trade shattered the balance of power among Galinhas villages as described above. From a domestic standpoint, increasing tensions were another episode in a long history of commercial rivalries, this time propelled by the emergent trade in human bodies. Around 1805 two big men (kpakoisia), Fan Souner and Siaka, stopped paying tribute to their overlord (mahawai), Carribil. To settle the dispute, Mattier Roger, the eldest leader, summoned a palaver, an official council attended by the ruling elite to administer justice and reach consensus on legal, political, economic, and religious matters affecting community members.Footnote 65 Each faction sought support from their respective British tenants. Fan Souner went to John Lascelles, who provided him with forty slaves and puncheons of rum; Siaka received the same from William Crundell, while ‘prince’ Carribil got support from a Mr. Willing. Carribil, knowing that Siaka and Fan Souner had bribed Mattier Roger and that his enemies had planned to assassinate him, ‘removed all his goods that night, and the women and children, and dug up the bones of his father and carried them with him’.Footnote 66 One of the warriors loyal to Carribil, Stephen Rogers, who descended from an old lineage of Eurafricans, was killed and dismembered. Carribil, followed by the Krim people, returned to Galinhas and burned down some towns and factories. The people from Mano and Tewo, allied to Carribil, addressed the ‘confederate chiefs of Galinhas’:

You tell the white people to pay no duties to the king's son, and they listen to you, though they know that Carribil is heir to the late king, and no King has been made in his place. No: we will join with Carribil, and drive all the white people away, for it is they who make you so proud, and they, at the bottom, excite all the trouble in the country.Footnote 67

As a result of the war, ‘the white people were all driven away; and none got off without great loss.’Footnote 68 A letter from an American slaver confirms the expulsion of the British slave traders from Galinhas. In 1807, captain Joseph Wood of the US slave ship Mary wrote to the commercial firm Gardner and Dean, owners of the vessel in Newport, Rhode Island, that ‘the natives have driven all the white traders from the Gallinas, which of course must be injurious to the trade.’Footnote 69 With some interruptions, the war continued for more than a decade until its final resolution in the 1820s.

Two supporters of Carribil related the events to John Kizell, a former slave from South Carolina living in Sherbro as an abolitionist.Footnote 70 Kizell, in turn, sent a report to the British authorities in Freetown, which remains the only known existing account about the conflict. In Kizell's story, the war was caused by ‘white people with respect to the prices of slaves and the duties’, who encouraged the conflict because ‘it would furnish them with the means of getting slaves.’ These words are consistent with the abolitionist narrative and the broader European perception of Africans as easily susceptible to white manipulation. It is difficult to assess the veracity of Kizell's account, nor should we accept his claims that African chiefs were subordinate to ‘whites’. Many Africanist historians now agree that precolonial African landlords controlled most regions during the transatlantic slave trade age. The Vai saying ‘sunda ma gara, ke a sunda-fa’, or ‘a stranger has no power but his landlords’, summarized Galinhas's power relations.Footnote 71 Finally, as shown below, wars did not necessarily mean more profit for the slave traders.

Around 1809, warring parties had reached a truce, and the white traders were allowed to return. This coincided with the settlement of US traders in the region. In 1810, Chiefs Siaka, Fan Souner, Dewara Soba, Mattier Roger, and Senhor Medeina granted the American Charles Mason ‘and his factory every protection in the country, and free permission to cut wood, thatch, and get water and mud and anything requisite to the Factory’ in exchange for fifty bars of tobacco, one cask of rum, and gunpowder.Footnote 72 Siaka was Mason's main landlord. Thus, when Mason sailed to Cuba in 1811, he had left behind his British partners and a network of Vai chiefs’ loading vessels with captives bound for Havana. As already explained, the number of slave ships heading from Havana to Galinhas increased by the years.

In mid-1816, the Iris transporting Faber to Africa arrived at Sherbro, between Freetown and Galinhas, where the renowned ‘mulatto’ slave dealer William Tucker welcomed the crew. During a dinner of fowls and rice hotly peppered and yellowed with palm oil, Tucker confessed that he met Jacob Faber when he managed his Rio Pongo factory. This revelation indicates the extensive network of traders traversing the West African coast. On 25 August 1816, the Iris anchored off the Kerefe River, where there were ‘several schooners under Spanish, French, and Dutch colors waiting for slaves, all clippers built in Baltimore’.Footnote 73

By the time Faber disembarked in Galinhas, the region was on its way to becoming a thriving slaving hub supplying the increasing demand from Cuba. People searching for new living opportunities migrated to the coast to find employment in the service economy surrounding slave markets. We can only guess the demographic impact of the growing commercial activity on a region with relatively infertile soils and a politically fragmented society. Competing chiefs wanted to get what they considered a fair share of the trade. Thus, demographic pressures and preexisting political tensions boosted by the increased demand for slaves were ingredients for the soon-to-come sociopolitical turmoil.

On 13 November 1816, a few days after disembarking in Galinhas, Jacob Faber wrote to his partners in Havana: ‘A civil war has broken out between both sides of the river.’Footnote 74 The conflict that Faber described manifested between two African chiefs, Siaka and Amara Lalu. It was not motivated by ethnolinguistic or religious considerations; both Siaka and Amara Lalu were Vai by birth and Islamic in belief.Footnote 75 Instead, the war was a rupture between members of the same lineage, descent group, or clan: Siaka from the Passii Massaquoi chiefdom and Amara Lalu from the Kiajua Massaquoi chiefdom.Footnote 76 According to inconsistent oral traditions, Siaka was either Amara's father, stepfather, or possibly uncle.Footnote 77 Theodore Canot described the war as a ‘family feud’:

The principal parties in this family feud were the Amarars and Shiakars. Amarar was a native of Shebar, and, through several generations, had Mandingo blood in his veins; Shiakar, born on the river, considered himself a noble of the land and being the aggressor in this conflict, disputed his prize with the wildest ferocity of a savage.Footnote 78

Faber sided with his landlord Siaka. ‘I have taken residence in the strongest side,’ he wrote to Havana, ‘the kings and chiefs here are very happy I have come to live with them.’Footnote 79 By December, Jacob Faber had moved to Siaka's village, Gendema, Galinhas's future capital. Gendema, located less than four miles from the mouth of the Kerefe River, was the main stop along the routes taken by caravans coming from the interior. In 1819, the British missionary John B. Cates described it as a prosperous town:

The place is strongly defended: there are many cannons of different sizes, some mounted and others not, with a quantity of small arms and spears. The town contains about 150 houses and 500 or 600 inhabitants at this time, but in time of war, they amount to 1,000. The houses are . . . made of mud . . . . They stand in general, four or five together, surrounding a small irregular square, in which the people sit lounging about or playing. The one in which the king's principal residence stands is the largest and has four houses: one side, is his sleeping house, opposite to this, is his store, on the other side, is his great house, as it is called; which is a large room for receiving his guests, furnished with a few chairs, a large table, a chest of drawers, and some boxes all round which serve as benches to sit upon; the walls being adorned with mats and the skin of leopards which had been killed by them, with several large looking-glasses and some common prints. The house opposite to this is his armory, which is open on the side next to the square, so as to display his cannon and other arms deposited.Footnote 80

In exchange for protection, Jacob Faber had to supply Siaka with resources, restrain from trading with the enemy, and take up arms on his behalf if needed. A contract signed on 22 December 1816 between Siaka, other chiefs, and Faber set the tone of the relationship:

Mr. William Gomez, Mr. Schaker, and Mr. Rogers, principal chiefs of the north side of Galinhas, currently engaged in the war that unfortunately exists, warn Mr. Faber that he cannot, and it is not possible hereafter, to allow him to supply their enemies with goods on the bars of both entrances of the river Galinhas. That they will allow him to load his properties at all times with no impediments or disturbances, and they agree and promise that if they can do any favor to Mr. Faber in helping to load, they will do it with the utmost pleasure. If Mr. Faber were willing to visit Mr. Gomez, Mr. Schaker, or Mr. Rogers, he could do it with all confidence at any time since you will be considered as neutral in this unnatural war. If Mr. Faber, at any time, sends his crew to any of the said chiefs, they promise that they would not be bothered or detained. Signed in Galinhas by W. Booth, Gomez, Mr. Shacker, and Mr. Roger on board the schooner Iris from Boston on December 22, 1816.Footnote 81

As this contract shows, Faber had to respond to Siaka and other principal chiefs in the region, such as Gomez and Roger. The Gomez family descended from a Portuguese lançado who settled in Bissau in the late seventeenth century.Footnote 82 By the early nineteenth century, branches of the family were scattered along the Upper Guinea coast. In Galinhas, there were two principal Gomez brothers, William and Charles, who had taken different political paths during the war. While William had pledged alliance to Siaka, Charles supported Amara Lalu.Footnote 83 The missionary Cates described his impressions of a visit he paid to Charles Gomez in 1819:

Mr. Gomez received an education in England, and apparently a good one; though he now lives in the fashion of the country, with a loose cloth around his body, and half a dozen wives for servants. He conversed freely and seemed to possess considerable knowledge of the affairs of England, though it is sixteen years since he was there.Footnote 84

The Rogerses descended from the British merchant Zachary Rogers, who settled in Sherbro in the late seventeenth century. Like the Gomezes, Rogerses could be found on both sides of the conflict and all over Galinhas. After generations of marriages and alliances, some were closely related to the Pasii Massaquois, while others were linked to the Kiajua Massaquouis, each with a separate territory.Footnote 85 In the early nineteenth century, the Rogerses allied with Siaka lived in Mina, a village located in the mouth of the Kerefe and the final stop on the slaving path coming from the interior.Footnote 86

Despite what seems a clear-cut division between political groups, the reality of the war was more complicated. Alliances among villages, chiefs, and merchants shifted frequently. Behind the scenes, new coalitions were forged, and allies could quickly become enemies. It is impossible to reconstruct the details of shifting alliances, but documents produced by Faber and others offer glimpses. For example, Howland's description shows a much more complex picture of the relationship between the Gomez brothers:

The two scoundrels managed to be made chiefs over different tribes, and mutually agreed to make war and lead their men into ambush alternately to take them prisoners for slaves and divide the spoil between them. One had a town on the Galinas and one on Sugary River near Cape Mount. We heard them boast of their exploits over their wine at Faber's table.Footnote 87

Jacob Faber himself, despite agreements with his landlords, provided merchandise to the opposing faction. In a letter from January 1817, Faber asked his partners in Havana for goods for ‘two brothers, the main chiefs in Mano's party’, William and Charles Gomez, supposedly enemies.Footnote 88 Years later, he paid the price for his duplicity. Despite his shady business, Faber considered himself a fair judge of others’ political conduct. In a letter to his partners from July 1818, Faber wrote that ‘the natives here do not have any law or customs to make them accountable for any moral or serious obligations, they are divided among different towns, each chief does not have any other law for his behavior than his own will.’Footnote 89 Even though Faber's words reflected the condescension of most white men in Africa, his attitude was grounded in the profound instability in the region:

When interests are at stake — Faber said — the promises or good faith of an African nation cannot be trusted, and they take advantage of them the first opportunity they have. Strength is the only thing that rules here, the only one respected, and the best and most secure reasoning that can be used.Footnote 90

With such a predisposition towards his neighbors amidst a very hostile environment, Faber got ready for worst-case scenarios. He continuously asked his partners in Havana for resources to protect himself and his properties. Most of his original companions, such as Stephen Goss, had died from diseases, and Faber asked in many letters for six or eight men to ‘protect the factory and the merchandise’. He believed that such numbers of whites would cause an ‘impression’ among the natives.Footnote 91 The replacements, however, never arrived.Footnote 92 He did receive more resources — boats, cannons, and muskets. Yet without loyal men, as he soon realized, firearms were at best futile and, at worst, a magnet for plunderers.

Faber plied his landlord Siaka with cannons, grenades, catapults, gunpowder, boats, and luxuries such as tobacco, sugar, fabrics, wines, or cheese. On one occasion, Siaka sent to Havana the tail of an elephant, a sign of royal authority, to be embroidered in silver. The request was fulfilled in the spring of 1817, as noted in the ledger of the schooner Circasiana.Footnote 93 A letter on board explained that ‘Ciaca's [sic] orders are inside a tin box except for the hat that is outside wrapped in paper, [on] which costs are listed. We hope that they are of his liking.’Footnote 94 Adam Jones has assessed the importance of these goods for Siaka in winning the war:

Siaka's armies depended to a large extent on imports of gunpowder, guns, iron, lead, and (perhaps) cannons. He also needed tobacco, spirits, and other articles to reward warriors. Imported merchandize was also essential for arranging marriages and meeting obligations to one's in-laws. In this sense, the Galinhas kingdom was built upon the slave trade, although it was also a product of Siaka's political skills.Footnote 95

In addition to fulfilling Siaka's material needs, Faber had to join forces in case of an attack. On 2 March 1817,

between 3 and 4 in the morning, the enemy attacked the city where I reside, intending to take it by assault. This gave me a reason to amuse myself for two hours with my cannon. We expect another visit any day, and I hope that their success will be as when they lost their canoes, boats, a canon, some weapons, and had several deaths and prisoners.Footnote 96

We have no details for most battles, but a decisive one took place in mid-1818 when Siaka attacked Amara Lalu's village on the Moa River's west bank. Siaka plundered the place and captured ten prisoners whose heads were fixed on the posts forming the fence.Footnote 97 Defeated, Amara Lalu resettled on the opposite side of the river, close to today's town of Male.Footnote 98 Siaka achieved control over the most critical commercial channels in Galinhas, the estuaries of the Kerefe and Moa Rivers, where most slave-trading transactions took place. Amara's region of influence was restricted to the area between the Moa and Mano Rivers. However, the war was far from over.

The support that Faber lent to Siaka is a typical example of the relationship between landlords and strangers, as observed everywhere in West Africa. In this case, it was the beginning of many decades of partnership between Siaka, his descendants and many Spaniards who joined, in the 1820s, the slave trade in Galinhas. The consequence of this cooperation is evident. Cuban resources and the increasing demand for captives played a pivotal role in the victory of Siaka and the foundation of the Galinhas kingdom. The expansion of this transatlantic partnership also made possible Siaka's inland expansion.

Faber's records also offer unique insight into the interplay between warfare and the slave trade during the formation of what we could consider a predatory state. Based on what the abolitionists claimed and most historians have argued, we might believe that warfare was the ideal environment for the slave trade to thrive since it would generate more prisoners to fill the slave ships. Although this was true for already established political entities with well-defined slaving frontiers, the argument is less tenable when we look at the origins of a predatory state. When war broke out, Faber, a man with a long career as a slave trader, felt that the war was good news. On 13 November 1816, days after the beginning of the war, he wrote a reassuring letter to his partners:

I consider this event to play favorably for my future operations since it will be the cause for prohibiting access of competitors; while this state of affairs continues, I will have the field open for my interests. I have positive reasons to believe that there will be an abundance of slaves to be acquired.Footnote 99

Faber soon realized that he had miscalculated the consequences of warfare for both his business and personal wellbeing. He never fulfilled the number of slaves he had committed to deliver to Havana; the captives’ ‘quality’ — defined in physical health and appearance — was undesirable, and their costs were higher than usual. Years later, he had to explain to an ill-informed Cuban court the consequences of the war. Faber, contrary to his initial hopes, had learned that wars were disruptive when they occurred on his doorstep.

The transatlantic slave trade relied on a fragile equilibrium between peace on the Atlantic shore, where the factories were located, and warfare in surrounding regions, where most slaves were captured. An illustration of that assertion is what a British trader visiting Freetown from Galinhas told Macaulay in the 1790s. The slave trade, he said, ‘caused wars and accumulation of miseries’ in the hinterland, but not on the coast, where peace was maintained to keep the ‘path open for the trade from the interior’.Footnote 100 Jones has rightly concluded that ‘too much warfare was bad even for the slave trade, especially if fought near the coast since it prevented interregional commerce.’Footnote 101 The consequences of the war were immediately felt not only in the interregional or Atlantic commerce but, most importantly, in the everyday life of ordinary people working on the production and service economy underpinning the slave trade.

Coastal slave trading operations required security to access, purchase, imprison, feed, guard, and sell the captives. Inhabitants of neighboring villages depended on social peace to provide necessary services such as farming, transportation, security, maintenance, and trade. War drove many people out of the region, while others were drafted or otherwise withdrew from productive activities. Since the land remained uncultivated and crops were not harvested, there was no food for the local population, the merchants, the slaves, the visitors, and the ships leaving for the Americas. At his arrival at Galinhas in 1816, George Howland vividly described the situation:

The different tribes, or, I may say, the same tribe in different towns along this part of the coast, were all at war to make prisoners of each other to sell them for slaves, but the far most significant number came from the interior. There was almost a famine in the place. The natives were so engaged in war and slave dealing that the ground was left uncultivated. Many actually starved in this land of plenty or subsisted only on its spontaneous productions, which were not now in season.Footnote 102

To illustrate the social disruptions caused by wars, we can follow a typical slaving operation from the moment the caravans arrived from the interior to the loading of the captives onto the ship. Slaving caravans arrived at Galinhas by foot from Mandingo, Mende, Krim, and Gola territories or in canoes from neighboring regions such as Sherbro and Cape Mount.Footnote 103 Records describing the wars in the interior and the ethnogeographical origins of the captives are scarce. To fill this historiographical lacuna, scholars have used the lists of ‘liberated Africans’ rescued by the British from slave ships, which contain the captives’ African names and ethnicities.Footnote 104

Philip Misevich has found that Africans sold between Sherbro and Cape Mount originated within sixty miles of the coast with ‘a heavy concentration of captives coming from Mende- and Sherbro-speaking areas’ — a regional pattern of captures identified in other regions in West Africa.Footnote 105 Of 4,567 enslaved persons identified by Misevich, 54 per cent were Mende/Sherbro, 19 per cent Kissi/Kono/Kuranko, and 9 per cent Temne, followed by minor numbers of Limba, Fula, Mandingo, Loko, and Susu. The Vai, in sharp contrast, constituted only 2 per cent of the liberated Africans.Footnote 106

The low numbers of Vai confirm the historical nature of the system of enslavement in Africa.Footnote 107 As elsewhere, enslavement in the Galinhas kingdom relied upon the distinction between the ‘we’ (the insiders, those holding full kinship status) and the ‘others’ (the outsiders who were potentially subject to captivity).Footnote 108 It was crucial for the social stability, legitimacy, and acceptance of slavery in Galinhas that the Vai inhabitants of the region were sure that they were unsuitable for enslavement in ‘normal’ circumstances. However, wars made those cultural boundaries more diffuse, creating confusion and a sense of social insecurity. Misevich's data comprises mostly slaves ‘liberated’ after Galinhas's slaving frontier was already established. However, before 1820, the number of enslaved Vai people might have been higher due to the coastal war.

After reaching the slave depots in Galinhas, caravan leaders discussed business with chiefs and traders. The head of the caravan, Faber said, ‘is treated with courtesy and civility. A portion of the rich merchants are Mohammedans, and they see as a particular demonstration of respect that a glass of wine is given to them.’Footnote 109 While the factors inspected the slaves, the head of the caravan and his people made sure the quality of the merchandise received in exchange, such as fabrics, cloth, spirits, coffee, tobacco, iron, firearms, gunpowder, metallic pots, sea salt, or any luxury good, was worthy. During each of these transactions, men and women entertained the visitors, transported the merchandise, cared for the slaves, secured the factories, built and maintained the barracoons, and ensured the captives remained under control. War disrupted these seemingly mundane activities.

War also caused severe shortages of food. ‘The country’, Faber wrote in December 1816, ‘is in a state of misery’ for which it was ‘impossible’ to find rice, a staple that had been for centuries the most important crop produced in Galinhas. A sense of fear and instability made its cultivation and harvesting impossible. On several occasions, Faber had to sell the slaves reserved for his partners in Havana

for not finding rice at any price . . . [T]he harvesting is missing across the country, this is the season to pick up the rice, and you do not hear anything but melancholy and cries of hunger. . . . The negroes I had for sale are skeletons.

For the rest of his stay in Africa, the situation did not improve:

Because of this country's dreadful state and the lack of supplies, there is no trade because the negroes cannot be stored, and, unfortunately, this penury is not restricted to this district, but it is everywhere on the coast and the interior.Footnote 110

When the ships — mostly small schooners between 70 and 150 tons — arrived in Galinhas, the merchandise was unloaded and carried to different factories and villages along the river. While the factor gathered the slaves, the ship sailed to neighboring regions such as Cape Mount or Sugary to obtain wood, water, and rice and preserve the crew's health by keeping a distance from the coast. For a vessel expecting to carry 150 slaves, the time to complete the cargo was usually from forty to fifty days, while two months were required for 200 captives.Footnote 111 Once the human cargo was assembled, the ‘shortage or necessity of boats’, Faber said, made all these activities extremely difficult. The people that took care of this job, such as the Kroomen, refused to do it because they ‘were scared of being apprehended’.Footnote 112 Ships remained longer in the region, which meant increased mortality for sailors. Thus, surviving crew members of the Iris were stranded in Galinhas for ten months before embarking for Havana, and half of them died. The captain wrote:

Our provisions were bad. Our bread got wormy from the humidity of the climate; our only food was poor Salt Beef and wormy bread. No tea nor coffee, nor vegetables of any kind, nor could we get any from the shore on account of war and the famine. We sold all the clothing we could spare to the natives for fruit and a few yams and cassava.Footnote 113

For the return voyage, slave ships required food, water, and firewood supplies for at least six weeks. These items became hard to acquire, and Faber often traveled to other regions such as Cape Mesurado to get them. However, as Faber frequently complained, not even imported supplies were sufficient. On some occasions, he had to send the slave ships ‘without a sufficient amount of water and firewood’, for which they had to stop in other places, which increased the risk of capture.Footnote 114 Extended stays in Galinhas, losses among the crew, and the purchase of malnourished captives eroded profits.

The rampant violence in Galinhas not only disrupted business, but it also increased the risk for traders and visitors. As his requests for protection show, Faber was well-aware of the dangers. Did he exaggerate the situation to receive more resources from his financiers or, later on, to make his case in court? George Howland profoundly disliked Faber, but he wrote that ‘Faber feared the native might plunder him if he kept a large quantity on hand.’Footnote 115 His fears became a reality on several occasions. In December 1816, Faber's factory was plundered while he was in Cape Mesurado searching for rice. A few months later, a group of men stole a canoe, some tobacco, and one slave. ‘I am sure’, he wrote, ‘that they could commit more depredations if attempted’. By July 1818, Faber's relationship with neighboring chiefs worsened. ‘Currently’, he wrote, ‘there is in this country a preying and thieving spirit [I] never saw before.’Footnote 116 The war, in sum, added to usual insecurities.

In 1818, Faber learned about a plot orchestrated by Amara Lalu, other chiefs, and a group of Freemason US traders and captains to take over his trading outpost in the Kerefe, ‘fortify the mouth of the river[,] and establish a monopoly’. Among the conspirators was William Gomez, his supposed ally. In March, as described at the beginning of this article, Faber's factory was attacked; he was imprisoned and carried to a village in the enemy's territory close to the Mano River. After a few days, he was released and went to Gendema to request justice from Siaka for ‘the cruel manner [of treatment] he had been subjected to, and the abominable and barbarian way he was robbed’. After receiving from Faber 500 bars to take care of the matter, Siaka summoned a palaver, which concluded that William Gomez had colluded with Amara Lalu in the attack. The perpetrators were only fined. Faber had fallen out of Siaka's favor.Footnote 117

On top of local disruptions, British suppression policies added another layer of challenges to Galinhas's commercial operations. Portugal in 1815 and Spain in 1817 agreed with Britain to ban the slave trade north of the equator, which de jure made illegal the presence of Spanish slave ships and traders in Galinhas. Faber knew, as he had experienced in 1814 when the British had burned down his factory in Rio Pongo, that it was just a matter of time before Freetown took more direct actions against Galinhas.

In July 1818, he wrote to his partners that ‘the mistreatment, bad faith, and betrayal that lately I have received do not allow me to stay here longer. I beg you not waste time in getting me out of here.’Footnote 118 In September 1819, Faber returned to Cuba, where he had to face multiple lawsuits from his disgruntled business partners. Nevertheless, despite all the obstacles he faced in Africa between 1816 and 1819, Faber managed to send 1,691 captives to Cuba. He died in his home country before a final settlement for the legal case was reached.

In the early 1820s, Siaka gave Amara Lalu his daughter in marriage in exchange for political loyalty.Footnote 119 Peace was achieved in Galinhas, and the kingdom consolidated and expanded in the following decades. Siaka pushed the slaving frontier inland, and, on the coast, the socioeconomic activities that made the transatlantic slave trade possible returned to some sense of normalcy. While the conflict lasted, slave ships could only complete their cargoes by calling at different markets in surrounding ports. The conditions had changed. A British report from September 1822 acknowledged that ‘the slave trade has much increased in the last four years’ and that a ship could now embark her slaves in ‘less than two hours’.Footnote 120 The numbers of slave exports made the case clear. Whereas between 1815 and 1820 around 2,900 Africans embarked in Galinhas, during the next quinquennium, 1821–6, the numbers almost tripled to 7,800. Between 1827 and 1856, when the last slave ship departed Galinhas to Cuba, an additional 21,600 Africans were shipped to the Americas. After excluding those liberated in Freetown, 76 per cent of them were sent to Cuba.Footnote 121

The economic growth boosted by political stability attracted more ships and merchants. A French visitor stated in 1822 that he had counted between 14 and 16 white settlers, mostly British and Americans, but also two Spaniards. After 1825, the influence of Spaniards from Havana in Galinhas expanded. According to Adam Jones, ‘the Spanish had a greater impact on Galinhas society than any other non-African nation. Nearly all the Spanish traders were agents of firms based in Havana.’Footnote 122 This massive influx of Spaniards to Galinhas could never happened without the American connection created by Mason, Faber, and others. Among the nearly thirty Spaniards who settled in Galinhas between 1825 and 1850, one was particularly infamous. Pedro Blanco Fernández de Traba (1794–1854) sent thousands of enslaved Africans to Havana in alliance with his father-in-law and landlord Siaka.Footnote 123 Among the captives they sent to Cuba were those who rebelled in the schooner Amistad in 1839.

In the 1830s, Siaka, supported by his loyal mercenary Mende warriors, expanded his territory thirty miles inland by waging new wars, which, in turn, fed the growing slave market.Footnote 124 In what used to be a fairly deserted coastline, many factories, barracoons, and other adjacent trading compounds were erected with lookout posts a hundred feet high. Men continually watched the horizon with telescopes and used signaling systems to communicate the arrival of slave ships or cruisers.Footnote 125 The system was perfected, the population expanded, and the commercial routes with the interior multiplied, reaching as far as Futa Jallon.

In the mid-1830s, war broke out again in Galinhas against Amara Lalu, which resulted in his decapitation in 1842.Footnote 126 After Siaka died in 1843, his son Mana took his place as the ruler of the kingdom. Well respected, with a stable network of subordinate alliances and supported by other chiefs, Mana expanded his influence as far as the Mano River. Galinhas's ‘grandeur’ under the first years of Prince Mana could be illustrated in the wealth of its capital, Gendema, as described by Reverend James Beale in 1850:

The town greatly surprised us, the houses being so substantial and well built. I was conducted to the Prince's house, built much in European style, with board floors, partitions, doors, and windows, all well made. The houses are surrounded by piazzas; there are rooms at each end, with a large open space in the center. The houses are also furnished in European style, with pier and other glasses, crockery, sofas, chairs, &c. In the yard, there saluted us about forty of the king's wives, with only a narrow strip of cloth around their waist; they had a very novel appearance, being adorned with every kind of gold, ivory, and silver trinkets.Footnote 127

Mana, nevertheless, presided over the decline of the kingdom induced by major British attacks, abolitionist pressures, the Zawo slave revolt, and British and Liberian colonization efforts, but most importantly, the end of the Atlantic slave trade.Footnote 128 After Mana died in 1872, the decay of the kingdom was sealed. Without having environmental or demographic conditions to adapt to the so-called ‘legitimate commerce’, people left the region, trading outposts closed, and few villages survived under conditions that little resembled the old days. In 1896, the British declared Galinhas a protectorate and part of Sierra Leone.

Almost a century later, in 1978, historian Adam Jones visited Gendema where he saw only the shadows of the past:

At Gendema, which was the Galinhas capital for most of the nineteenth century, there are no more than twenty houses; and the only reminders of the town's history are some tall cotton trees (the remains of a war-fence), the tombs of three kings and thirteen cannons, half-buried in the sand.Footnote 129

CONCLUSION

The interplay of Atlantic and local factors that shaped the evolution of many West African coastal communities during the slave trade era can be seen with particular clarity in Galinhas’ rise and decline. The Anglo-American abolition triggered a relocation of slave trading actors, networks, and routes within Upper Guinea, the Americas, and across the Atlantic. Within Upper Guinea, the British abolition prompted a redeployment of markets from long-established regions to marginal ones such as Galinhas, which welcomed more traders and ships. Within the Americas, US federal law prohibiting the transatlantic slave trade impelled US traders to move their operations to Cuba and some African regions like Galinhas. In doing so, US slavers created a new transatlantic slave-trading corridor between Cuba and Galinhas. By the 1820s, Cuban-based traders inherited and took over that trade from the Americans. The Galinhas-Havana corridor dramatically increased in size and continued expanding until its slow decline in the 1850s.

Traditionally, historians have written the history of some African regions during the transatlantic slave trade era from sources located mostly in metropolitan archives such as England, Portugal, or France. Cuban colonial records are, like those from Brazil, exceptional in that regard. This archival evidence sheds light not only on the early-nineteenth-century Atlantic changes that enabled the connection of Cuba and Galinhas but also on the rarely explored foundational moment of one of the predatory states that arose during the slave trade era. The increase of the slave trade in Galinhas led to wars among chieftaincies, which concluded with the creation of the kingdom of Galinhas, headed by Siaka. There is a consensus that warfare and raids were beneficial for the transatlantic slave trade since they produced more captives for the Atlantic market. However, that assertion is less evident when we look at the moment of the creation of an African slave-trading state. Warfare was detrimental to social or commercial activities underpinning the slave trade. Certainly, wars generated more slaves, but they also shattered the social stability so much needed for other economic activities in the region besides enslaving. The main explanation for such a counterproductive effect was the coexistence of war and trade in the same physical space, or, in other words, the lack of a slaving frontier. The importance of sociopolitical stability becomes clear by looking at the period after Siaka won the war in the early 1820s. After the kingdom emerged and pushed its borders inland, the production of slaves increased, and more traders and vessels were attracted to the region. The kingdom flourished until the end of the trade.

Jacob Faber's records, combined with other Cuban, American, Spanish, and British archival sources, point to the beginning of an extensive collaboration between the Passii Massaquoi dynasty and Cuban-based merchants. Since the beginning of the war, Siaka received various resources from Havana, including firearms, which allowed him to win the war and increased his power. That collaboration expanded after the 1820s when more Cuban-based traders settled in Galinhas. The consolidation and expansion of the kingdom of Galinhas as a predatory state was possible because of the trading connection with Havana. In other words, the trajectory of the kingdom and the Cuban demand for slaves to supply the plantation economy remained for half a century deeply tied. Like any other economy dependent on the production of a single merchandise, once the slave trade with Cuba ended, and after failed attempts to redirect that commerce to the northern regions such as Rio Pongo, the kingdom of Galinhas collapsed.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Emma Christopher, David Eltis, Marial Iglesias, Adam Jones, Philip Misevich, Konrad T. Tuchscherer, and Alonso Villasmil for reading and commenting on the first drafts of this article.