In 1888, upon return from East Africa, the Scottish traveller Henry Drummond reported that ‘[p]robably no country in the world, civilized or uncivilized, is better supplied with paths than this unmapped continent. Every village is connected with some other village, every tribe with the next tribe, every state with its neighbour, and therefore with all the rest'.Footnote 1 This complex network of footpaths allowed for trade and communication on local, regional, and inter-regional levels across large parts of precolonial Central and East Africa. On these paths, a labour force of tens of thousands of porters mediated almost all transport.Footnote 2 In the closing decade of the nineteenth century, the new colonial regime saw itself confronted with this pre-existing infrastructure system after the German Empire had established its colony Deutsch-Ostafrika or German East Africa (1885/1891–1918) in the present-day countries of Tanzania, Rwanda, and Burundi.Footnote 3 While the biologist Drummond praised the region's interconnectedness, to German East Africa's young colonial administration the existing infrastructure seemed backward, irrational, and unreliable.Footnote 4

In the years to come, German colonisers would embark on a programme of spatial transformation, seeking to make the colony's vast interior accessible to European rule and commerce through the large-scale implementation of colonial infrastructure systems. While in the imperialist imagination this meant first and foremost railways, sufficient funds for their construction were initially not provided by the imperial metropole and only a few kilometres of tracks were laid. It was only in the wake of the Maji Maji War (1905–7) that the colonisers eventually pushed two railway lines inland. They reached their railheads in 1911 and 1914, respectively, the latter only months before the entire German colonial empire collapsed. Railway construction in German East Africa, therefore, stood not at the beginning of colonial occupation but followed a longer attempt to interlink space by more cost-effective means.

This article studies the conflictual history of infrastructure construction, use, and contestation in East Africa's transition period from the precolonial era to colonial rule. Its focus is on road building, the colonial state's primary spatial intervention during the period from 1891 to 1907, the years before the expansion of railways began in earnest. Investigating how an emerging colonial state engaged with established infrastructure systems, in which ways it sought to transform them, and why it failed to do so, the article seeks to illuminate two aspects. First, that the slowly progressing German conquest and consolidation of power in the 1890s and early 1900s did not simply replace pre-existing structures but most often had to engage, coexist, and even compete with them; secondly, that the spatial practices of African infrastructure producers and users along with their overt contestation of German power subverted any colonial re-organisation of space.

In making these arguments, the article adds to the study of African mobility in the German period. Previous research by Stephen J. Rockel and Thaddeus Sunseri has examined how East African caravan porters and migrant workers engaged with the colonial system, highlighting that long-established patterns of long-distance mobility continued to exist under colonial rule.Footnote 5 Sunseri as well as Christiane Reichart-Burikukiye also partly address the role of African labour in the construction of colonial infrastructure, shedding light on forced road works while also illuminating that thousands of men and women actively involved themselves in the business of expanding railways, either as construction workers or by selling supplies at construction sites.Footnote 6

The present article is the first study to thoroughly engage the road building programme in German East Africa. Building on the aforementioned studies, the following analysis advances the understanding of African activity in the process of infrastructure expansion. Making use of approaches derived from the vibrant field of Science and Technology Studies (STS) as well as the recent scholarship on mobility in colonial Africa, it places African agency at the heart of spatial transformation.

In recent years, a number of studies has moved beyond previously dominant narratives of colonial infrastructure as a ‘tool of empire’ theorised by Daniel Headrick as a guarantor of economic and political exploitation.Footnote 7 Instead, different scholars have directed a spotlight on local conditions and actors, and examined how they negotiated, contested, and appropriated technological interventions.Footnote 8 Studies by Jennifer Hart and Joshua Grace, for instance, explore how Africans embraced new motor technologies in Ghana and Tanzania respectively.Footnote 9 Hart demonstrates that Ghanaian entrepreneurs from the 1920s on invested in motor vehicles and expanded roads on their own account. In this way, she argues, African drivers and passengers created spatial relations which posed an alternative to colonial infrastructure networks.Footnote 10 In like vein, Grace examines the use of cars in colonial and postcolonial Tanzania, illuminating that motorised transport was originally introduced to facilitate the exercise of colonial power but was soon appropriated by African users and owners, who ‘transformed motor vehicles from a tool of imperial rule into an African technology’.Footnote 11 Embedding the car in the wider history of East African transport and thus writing an African-centred history of development, Grace calls on historians to defy exclusively Western notions of mobility and technology and instead take into account the ‘host of vernacular practices, technologies, and ideas about movement, its meanings, and its longer histories’.Footnote 12

Building on Grace's call and his notion of vernacular mobility, the present article proposes a further departure from the conceptual framing of many recent studies in STS and the history of technology. While research in the last decade has ventured beyond classical narratives, its focus often remained on European technologies and their adaptation and implementation in the Global South; be it cars, electricity, monoculture schemes, or railways. Given this emphasis, combined with a temporal focus on the twentieth century, many studies have paid particular attention to how Africans appropriated these imported technologies.Footnote 13

European engagement with African infrastructure, by contrast, has until now often evaded the historian's gaze. Important steps towards unmuting this history have been made in the various key contributions of Clapperton Chakanetsa Mavhunga.Footnote 14 Using the example of hunting in Zimbabwe, he shows how European outsiders adopted existing socio-spatial patterns and adapted themselves to them.Footnote 15 Most recently, John Cropper has investigated how local and imported systems of energy use intersected in colonial Senegal, observing that energy infrastructure ‘was not only a mix of European and African systems of knowledge and labor, but also a blend of localized, ethnic systems of material production’.Footnote 16 Adding to these pioneering studies, the present article helps to further promote the analytical shift of frameworks, away from western technologies and their adoption by Africans towards African technologies of movement.

This involves a re-conceptualisation of the concept of infrastructure itself, which is still predominantly framed in European terms. In line with the terminology suggested by Joshua Grace, the following analysis proposes the term ‘vernacular infrastructure’ to describe those networks and technologies developed from within Eastern Africa, in particular porterage and the paths on which porters moved. As we will see, imported and vernacular structures differed significantly in their purpose and conception of ideal users. Still, emphasising continuities rather than disruption, the article places colonial road works in the wider context of infrastructure production in the region since the mid-nineteenth century. By highlighting the longevity of vernacular networks of mobility, it seeks to reveal the perpetual dependence of colonial spatial interventions on African actors and their day-to-day activities.

Retrieving their experiences and agency from the colonial archive is difficult. The few sources produced by caravan travellers which we have at hand give only very limited evidence of their spatial practices.Footnote 17 To gain insights into their everyday activities, the analysis in this article reads the available colonial source material in two directions. Reading European records ‘against the grain’ allow us to retrieve practices and ideas of caravan travelers and entrepreneurs by understanding official circulars and regulations as responses to their activities. Additionally reading the colonial archive ‘along the grain’, as proposed by Ann Laura Stoler, helps us understand the ways in which colonial officials perceived their surrounding environment and how they dealt with it.Footnote 18 The information contained in these records can only be utilised by meticulously cross-referencing and layering source material of different origin.Footnote 19 In addition to published travelogues the following historical analysis thus draws on a novel corpus of unpublished source material recovered from different archival sites; reports and communication by the colonial administration, the government in Berlin, missionary societies, as well as field journals of individual German officials and travellers. Interrogating these sources, predominantly written in German language, the present article also sets out to contribute a case study from a comparatively understudied European empire to the growing body of literature on Africans as agents of infrastructure development.

By focussing on the activities of two African actor groups – producers (the residents of the Tanzanian interior) and users (caravan travellers) – and their engagement with infrastructure before and after colonisation, the following analysis provides new insights into the transformative effects of colonial rule and the resilience of African spatial practices. With this proposed actor-centred approach, the article conceives a research agenda for studying processes of production, appropriation, and contestation of different infrastructure systems, which hopefully will provide a starting point for future analyses beyond the East African context. My ultimate aim, then, is to demonstrate the feedback loops of infrastructure development in the colonial world: on the one hand showing how colonial authorities engaged with the existing (infra)structures of the world they encountered (which was anything but a tabula rasa); on the other hand contributing to a better understanding of the different ways in which indigenous actors responded to the colonial state and the spatial transformation it engendered.

The article starts with a brief sketch, based on the existing literature, of the development of caravan infrastructure and its primary users, human porters. The subsequent section scrutinises how European travellers and, after 1891, German colonial authorities engaged with the established system of circulation, in which ways they utilised it, and how and why colonisers set out to construct all-weather highways. The third section investigates how German state authorities organised workers for their road building projects and how those pressured into road works contested spatial interventions on the scene. To fully understand the struggles over space, the fourth section puts a focus on infrastructure users and their role in the process of colonial spatial transformation. Illuminating that the ideal users envisioned by German planners were not the real users of their roads, it explores how caravan crews interacted with the infrastructural arrangements provided by the colonial state, whether and how they used them, and to what extent they placed these new structures in relation to existing ones.

East African infrastructure before colonisation

Precolonial East Africa witnessed the emergence of a complex long-distance trade system. In the first decades of the nineteenth century, chiefs from the interior began to send pioneering caravans with ivory to the coast, most notably the Wanyamwezi of central Tanzania.Footnote 20 Around the same time, traders from the Zanzibar archipelago and the Indian Ocean coast pushed inland, trading imported commodities, such as rifles and textiles, for slaves, ivory, and other products from the interior.Footnote 21 Because vast parts of the region were infested with trypanosomiasis – a disease causing weakness, lethargy, and death in affected animals – almost every use of pack or draught animals in this commercial system was impossible. As Stephen J. Rockel has shown in his seminal study Carriers of Culture (2006), instead of animals the foundation of all trade caravans consisted of tens of thousands of professional porters.Footnote 22

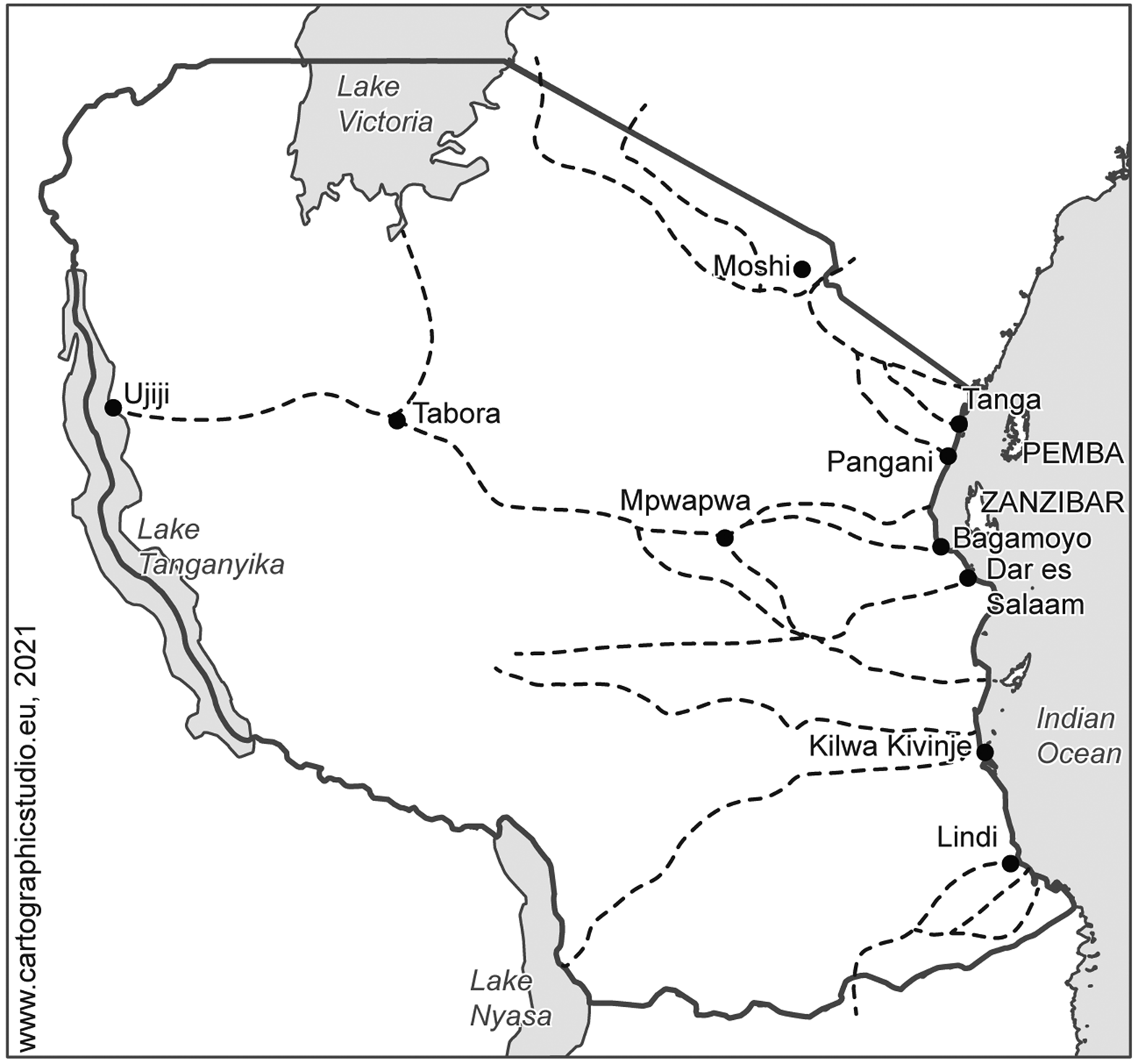

In the second half of the nineteenth century, three main trade corridors existed in today's Tanzania (Fig. 1): in the north, caravan routes stretched from the coast inland to Mount Kilimanjaro and further in the direction of Lake Victoria or towards Ugogo. In southern Tanzania, a second corridor ran from the coastal towns of Kilwa and Lindi to Lake Nyasa. The most important corridor was the so-called central route between the coastal towns facing the Zanzibar archipelago and Lake Tanganyika.Footnote 23 Rather than single paths, the routes in these corridors should be understood as clusters of different smaller trails, branching from or running parallel to each other.Footnote 24

Fig. 1. The three caravan sectors with the major routes as observed by German officials in 1891.

Source: Map by Annelieke Vries, adapted from BAB, R 1001/1107, 44.

The network of long-distance routes, as Adrian S. Wisnicki puts it, ‘constituted a complex spatial infrastructure – one that regulated the flow of people (caravan porters; slaves; Arab, Swahili, and Indian traders) and goods (ivory, gum copal) between the East African coast and interior’.Footnote 25 Because carts or pack animals almost never travelled along this network, it was human interaction that produced and remade its infrastructural manifestations. To participate in the long-distance economy and gain access to imported goods and firearms, different groups living in proximity of caravan routes organised a supply infrastructure. Earlier research by Rockel and other scholars has already pointed to their different activities: residents provided auxiliary transport workers, dug wells, or provided safe accommodation. Most importantly, many groups established marketplaces where caravanners could stop and resupply themselves with food and water.Footnote 26

In return for the provision of these different resources, residents (at least those of the central route) demanded a fee from travellers, known as hongo.Footnote 27 Of this system, we learn from a unique non-European travel account, written by the Swahili caravan leader Selemani bin Mwenye Chande, who operated in the central trade corridor on the eve of colonial rule. He reported from the central Tanzanian region of Ugogo that in every village that his party passed, they were asked to pay the tribute, usually in imported textiles.Footnote 28 Conflict over resources was another decisive factor in the establishment of long-distance structures. When chiefs and travellers could not agree upon an adequate sum, armed conflict was the result.Footnote 29 Villages or war bands also specialised in ambushing and raiding caravans while, at the same time, porters raided the stocks of villages in search of food.Footnote 30

By providing infrastructure, but also by blocking and destabilising it, many groups residing near important arteries of commerce engaged in processes of spatial transformation.Footnote 31 But it was not their activities alone that gave shape to the landscape. Being the primary — and often sole — users of caravan infrastructure, caravan travellers, too, played a crucial role in producing the network of long-distance routes, as witnessed by many European travellers.Footnote 32 According to Gerald Portal, the British Special Commissioner to East Africa, for instance,

it is well known that an African road consists simply of a footpath some ten inches wide worn in the grass by the constantly-passing naked feet of native villagers and caravan-porters. If, for any reason, such a path falls into disuse for a few months, especially during the rainy season, it is quickly obliterated by the rank grass, thorns, and creepers.Footnote 33

Not only were the footpaths marked out and maintained by the feet of those marching on them, but the users’ navigation through the infrastructural network also affected its trajectories on a larger scale. Rockel, whose research provides deep insights into the working conditions and everyday experiences of caravan crews, observes that caravans responded to both threats and incentives by travelling on the routes which suited them best: caravan leaders and guides could often choose between different paths running in similar directions. They made their porters march on the most accessible and safest track, bypassing geographical obstacles, avoiding war zones, famine regions, or excessive hongo, and following supply points, networks of kinship and joking relations (utani), as well as good commercial prospects.Footnote 34 ‘Caravan routes’, Rockel observes, ‘were ultimately selected according to their utility for trade and the ability of resident communities to produce a large enough surplus to feed the armies of porters that traveled them’.Footnote 35

The possibility to choose also implied that caravan routes could shift their shape if existing structures did not meet these requirements.Footnote 36 In cases where many caravans avoided specific areas, untravelled paths fell into disuse and vanished under grass, as described by Portal. Moreover, whereas major nodal points, such as the trade centre Tabora, were mostly fixed, new spatial links emerged through the mobility of caravan travellers. Rockel illustrated this process for the central trade corridor, in which a branch route running through south-central Tanzania lost its importance after the 1840s, when the inhabitants could no longer supply enough food for travellers, and was replaced by another route running through the above-mention region of Ugogo.Footnote 37

The provision of infrastructure in precolonial East Africa, to conclude this section, was socially organised on the ground, as the preceding discussion has demonstrated in at least three ways. First, the footpaths were the immediate result of human circulation on them. Second, critical supply infrastructure was provided by the interior population. Third, as a result of these different activities, the network itself underwent processes of adaption and reorientation. Its makeshift character notwithstanding, infrastructure production was integrated into complex relations between travellers and groups residing in the interior. Being produced by human interaction, the infrastructural arrangements catered to the needs of their users, their rationality lying in safe passage and, as Rockel concludes, in ‘the most basic and prosaic human requirements of food and water, as much as commercial and political considerations’.Footnote 38

Paving roads over well-trodden paths

In the second half of the nineteenth century, missionaries and self-proclaimed explorers from Europe entered East Africa in increasing numbers.Footnote 39 While they made extensive use of the infrastructure of caravan travel, these travellers soon came to perceive the existing arrangements as highly problematic, claiming that slaves were often employed as porters and that caravan routes were populated by slave raiders.Footnote 40 To future colonial entrepreneurs, the existing arrangements also appeared as a hindrance to economic exploitation. Because the paths allowed for human movement only, all goods had to be carried by porters. In this way, the development of a plantation industry beyond the coastal belt was impossible because products of comparatively little value, such as coffee, could not reach the coast without financial losses.Footnote 41 These alleged moral and commercial shortcomings demanded European intervention. In line with the proclaimed ‘civilising mission’, as Joshua Grace remarks, the structures predating European arrival, ‘required a robust technological intervention capable of replacing the economic and social networks that caravan infrastructures sustained. This is where the road and the wheel came in’.Footnote 42

In the decades leading up to colonial occupation, different private European ventures invested in replacing existing infrastructure with broad, paved roads. In mid-1877, the Imperial British East Africa Company completed the first kilometres of the ‘Mackinnon Road’, a road construction intended to allow for wheeled traffic between Dar es Salaam and the interior. The project was suspended with only a portion of the road completed.Footnote 43 As Karin Pallaver demonstrates based on the company's archival records, one reason for this construction freeze was that the local population was reluctant to construct and maintain the road.Footnote 44 Other European ventures suffered a similar fate, such as the ‘Stevenson Road’ in today's Zambia, a project that was cancelled after a few kilometres.Footnote 45 From May to August 1877, the Church Missionary Society also engaged in road building for vehicle traffic between the Tanzanian coast and its new station in Mpwapwa on the central route. To populate this road, the missionaries experimented with oxen, following a successful test-drive with an ox-drawn cart between the coast and Mpwapwa by the London Missionary Society in the previous year.Footnote 46 Of the animals employed by the Church Missionary Society, however, almost all died of trypanosomiasis.Footnote 47 By the onset of German colonial rule, there was still no beast of burden that could replace porterage. Lacking adequate users, the few vehicle-ready road segments built by Europeans had entirely vanished again, their tracks overgrown with vegetation.Footnote 48

In 1891 the German Empire took over control of what is now mainland Tanzania, Rwanda, and Burundi. Continuing the quest for a new infrastructure system, works on a first railway line began as early as 1893 in the coastal town of Tanga but advanced very slowly. Only forty kilometres of track were laid before the construction company filed for bankruptcy a few years later.Footnote 49 Large-scale infrastructure programmes were simply not affordable for the colonial project which was run as cheaply as possible by the German metropole.Footnote 50 For the time being, porter caravans thus remained at the centre of all logistical and commercial operations in German East Africa: not only did the established caravan trade boom immediately after the German takeover, with ivory accounting for a large share of the colonial economy, but state agents also organised thousands of (voluntary and involuntary) porters for state-run caravans and military campaigns.Footnote 51

Utilising vernacular patterns of movement, German authorities bound colonial mobility to precolonial networks. When the colonisers founded their first military outposts in the interior, they did so by proceeding along the footpaths of trade caravans. Later, the administrative stations in every district were located at already developed caravan hubs.Footnote 52 To the new administrators, however, it soon became apparent that the capacity of existing infrastructure was insufficient to host colonial mobility. Its fragility and annual breakdown after the rainy seasons, when paths became washed-out and impassable, brought colonial logistics to a standstill and put the state in a very precarious position: there could be no network of stations without reliable communication channels between them and no military dominance without fast and safe access to the hinterland in case of insurgencies.

Early on during their reign, on 17 August 1891, the colonisers had to learn that footpaths could indeed pose a danger to the colonial project. That day 5,000 warriors of the Wahehe, a group resisting the German expansion, ambushed a military expedition and killed 10 European officers, 290 soldiers, and 200 porters on a path near the town of Iringa.Footnote 53 To forestall such destructive events for the future, the colonial authorities had to make the existing route network usable for colonial purpose, as one of the few survivors demanded, declaring ‘that we will only fully be able to protect ourselves against such raids by upgrading the most important routes to broad roads’.Footnote 54

The major impetus of public works in the first years of colonial occupation was to make the existing network of caravan trails less dangerous to use for Europeans and more accessible for future vehicles. According to this agenda, important footpaths were to be transformed into highways, officially called barabara.Footnote 55 If we follow the dictionary originally compiled by missionary Edward Steere, since at least the 1880s this Kiswahili term had been used in Zanzibar to describe ‘a broad open road’.Footnote 56 The concept of a broad road was also applied in the Tanzanian interior: according to German planners, the ideal highway was three or more metres wide, had drainage channels on either side and was paved.Footnote 57

With the meagre sum of 120,000 marks, officials began in 1893 to construct the first barabara. Building efforts initially centred around two highways starting in the coastal towns of Tanga and Dar es Salaam. In the latter town, the new colonial capital, a force of 300 African residents worked on the first segment of a six metres wide road. To enlist them, the state authorities took advantage of a locust plague that ravaged the area in the same year, offering famine relief in exchange for labour.Footnote 58 Different station commanders in the Tanzanian interior simultaneously ordered local dwellers to rework existing footpaths to make them more accessible, for instance through bridge construction and bush clearing.Footnote 59 Labelled as Frondienst (corvée), local authorities conscripted these people — men, women, and children — from the vicinity of their stations with the help of local intermediaries. It was the duty of allied chiefs, village headmen, and newly-imposed Kiswahili-speaking paramount chiefs, so-called Akidas, to round up corvée workers for road construction and maintenance.Footnote 60

This mobilisation of African labour notwithstanding, German building efforts soon faced serious challenges. Work on the road out of Dar es Salaam was halted after a few kilometres in 1894 as a result of budget deficits.Footnote 61 Achievements on most other roads were short-lived as during the periods of rain — the main season from March to May and the lighter season in November — they became impassable and vanished again.Footnote 62 Those roads that survived into the dry season were covered by thick thorn bush and grass and thus impassable.Footnote 63

To clear the road at least two times per year was expected as part of the local population's corvée. However, as Michael Pesek has demonstrated, shortages of resources and manpower caused the exercise of colonial power to restrict itself to the few inland stations and their immediate surroundings.Footnote 64 Away from these administrative and military outposts it was very difficult for officials to check whether the villages really had sent corvée workers to carry out road works, allowing groups along the routes to ignore their duties.Footnote 65 In January 1896, all road construction in the colony was suspended for lack of financial means and engineers with only a few kilometres of roads being surfaced.Footnote 66

Colonial labour mobilisation and worker agency

When Eduard von Liebert became the new governor of German East Africa in 1897, he made road construction a primary task of the colonial administration.Footnote 67 Engineers were delegated from the colonial capital to supervise construction works in different parts of the colony.Footnote 68 While some of these projects reworked existing structures, others implied a departure from existing spatial links. In southern Tanzania, for instance, road building commenced in 1897 from Kilwa and Lindi to the interior. Meanwhile, work on the road out of Dar es Salaam was resumed while new roads were planned between Lake Nyasa and Lake Tanganyika as well as between Tabora and Mwanza at Lake Victoria.Footnote 69

A new tax order helped the Germans obtain the enormous amount of cheap labour required for these different construction sites. From April 1898 on, the government introduced a so-called hut tax of 3 to 12 rupees to be paid per annum in either cash or produce by every house and hut owner in the ‘pacified’ parts of the colony.Footnote 70 While the task to clear nearby roads was still expected as a tribute from local residents, additional road works were henceforth to be performed by tax defaulters, who were forced to work for the government.Footnote 71 A system applied by police commander Eugen Styx on the road from Lindi to Masasi proved particularly ‘efficient’. There, Styx had introduced a shift system in which one hundred tax workers per day were employed and replaced by the hundred workers of the next village as soon as they had worked off the village's tax debts.Footnote 72

Even Styx's labour regime, however, could not prevent the non-compliance of those pressured into road works. In eastern central Tanzania, the population of Kisaki opposed his command, reportedly proclaiming: ‘are we the slaves or debtors of Europeans? Each day taxes and public works, why oh why?’Footnote 73 Different groups across the colony defied the pressure to work for the state. In the Tabora district, a group of villagers refused to engage in road construction so that the local district office outfitted a military expedition in May 1899.Footnote 74 In the same year, the Moshi district at Mount Kilimanjaro, in which the overwhelming majority of colonial subjects paid their taxes in labour, witnessed unrest, too.Footnote 75 As the source of grievances, the missionaries of the local Leipzig Mission station identified the simultaneity of corvée and tax burden:

The main reason for the people's distaste was the way in which the natives were enlisted for corvée regardless of their financial needs. Without doubt, the maintenance of roads, bridges, etc. cannot be accomplished without their labour. Still, the question remains whether it is justified to demand these works from those who have already paid their hut taxes.… In the natives’ eyes, their enlistment without compensation strikingly resembles slavery.Footnote 76

If we follow the missionaries’ report, the people in Moshi voiced the same sentiment as those in Kisaki. They identified the obligation to construct and maintain roads as a form of ‘slavery by another name’, to refer to Eric Allina's description of labour regimes in colonial Mozambique; systems of unfree labour whose ‘practices had more than a passing resemblance to the exploitation of the now disavowed chattel slavery’.Footnote 77

But while the state apparatus responded to such open revolt with violence, for instance through a military campaign against the inhabitants of Kisaki in spring 1901, its representatives could not prevent the mere ignoring of their orders.Footnote 78 Even by the turn of the century, pressure to work on the state's construction sites was still inevitably reduced to the areas close to the coastal centres, the seats of loyal chiefs, as well as the interior stations. The nomadic presence of colonial officials and their allies allowed many actors along the routes to avoid or ignore their maintenance duties.Footnote 79 Evidence can be drawn from the hitherto unused source material produced by German travellers, such as the field journal of Georg von Prittwitz und Gaffron, who served in the colonial army and travelled from Mohoro in the coastal hinterland to the Iringa region in 1898. On one of his first marching days, he observed that ‘on the roadway the grass was cut on a width of two meters. This had been done at the behest of the Wali [the deputy officer] of Kilwa’.Footnote 80 Six days later, farther inland, the officer learned that the maintained road stopped ‘because the Wali's influence does not extend beyond the village of Kungulio’.Footnote 81

In reaction to such neglect, it became a common practice of state officials travelling in expeditions to either outfit their own porters with hoes and axes or to spontaneously recruit residents to march ahead and clear the roads.Footnote 82 Once the officials were gone again, however, this enthusiasm tailed off immediately, as even Gustav Adolf von Götzen, von Liebert's successor in the governor's office, acknowledged, speculating that the interior population ‘will, of course, vow obedience but think at the very same moment … that the district official is far away and so they will neglect their assigned duties’.Footnote 83

The consequence of this negligence was that even after the turn of the century colonial spatial infiltration remained limited and patchy. Of the planned highway out of Dar es Salaam, for instance, only the first seven kilometres were navigable with vehicles.Footnote 84 While there are no statistics on the total number of vehicle-ready kilometres around 1900, there is no doubt that the few existing segments of colonial roads represented only the smallest fraction of German East Africa's vast route network, which continued to be made of footpaths. Moreover, even the prestigious segments regularly broke down under bad weather conditions, displaying the same shortcomings as the roads built a decade earlier.Footnote 85 When Governor von Götzen, who had followed von Liebert in 1901, reviewed the efforts made under his predecessor and in the first years of his own term, he conceded in 1904 that every year during the rainy season most of the colonial roads succumbed to the rains: ‘travellers, then, are forced to march knee-deep in water or mud for hours and, sometimes, even to swim’.Footnote 86

From 1904 on, colonial infrastructure works received financial resources and metropolitan investment on an unprecedented scale. The German parliament granted a concession to build and run a railway line between Dar es Salaam and Morogoro, 180 kilometres inland, to a consortium headed by Deutsche Bank.Footnote 87 The parliament also granted von Götzen the massive sum of 10,800,000 marks, to be invested over a period of 18 years, for a grand-scale extension of highways across the colony. While preliminary works on the so-called Central Railway began, the government planned the construction of nineteen state roads. They included sections of the central caravan route, which was to be reworked, as well as roads from Kilwa to the rubber reservoirs in its hinterland, from Lindi to the Ruvuma River, and roads connecting Lake Tanganyika with Lake Nyasa and Lake Victoria respectively. These roads were to be prepared for year-round traffic with carts (Fig. 2).Footnote 88

Fig. 2. Ocker, ‘Road construction in Mufindi’, n.d.

Source: Image Collection of the German Colonial Society, Frankfurt am Main University Library, 016-1283-10.

Labour for this mammoth project was to be drawn from taxpayers. In March 1905, the Germans introduced a new tax of three rupees to be paid cash by every male colonial subject.Footnote 89 At the same time, it was decreed that any man could be forced to work in road construction for free – in addition to the existing road maintenance duties.Footnote 90 This burden added more tension to the already smouldering conflicts in German East Africa. In April 1905, the Dar es Salaam-based weekly Deutsch-Ostafrikanische Zeitung warned that in the Kilwa district frustration grew among the Ngindo people: ‘Quite apart from the unpaid cleaning of the barabara – a practice common to all districts – the new construction of large, public thoroughfares seems a risky step that may serve to embitter the Wangindo because it conflicts with their rubber collection and field preparation [activities]’.Footnote 91

In mid-1905, the Maji Maji War broke out in southern Tanzania, from where it spread over large parts of the colony. The uprising had many causes: heavy taxation, the breakdown of patron-client relations, and a loss of control over the economy and environment through the imposition of cotton cultivation and wildlife ordinances all played a role.Footnote 92 Compulsion to work in road construction and maintenance was another crucial factor in the conflict.Footnote 93 Evidence is found in the Lindi and Kilwa districts, where the uprising first broke out. As the Deutsch-Ostafrikanische Zeitung had predicted, Ngindo communities were among the first to revolt against German oppression.Footnote 94 During the war, they did not only fight the state's representatives but also its physical landscape, reportedly sabotaging the kilometre marker stones along the Kilwa–Liwale road which previously they had been forced to build.Footnote 95

The Maji Maji War ended in August 1907. The gradual suppression of the war initially facilitated labor recruitment and helped promote the extension of highways as the state authorities drew on a cheap force of chained penal workers.Footnote 96 However, when von Götzen was dismissed from the governor's office in consequence of the uprising, the focus of colonial engineering shifted from roads to railways.Footnote 97 From 1907 on, the central railway was extended with public funds to Lake Tanganyika. Simultaneously, the railway line in northern Tanzania, on which construction had slowly continued after the German state bought up the existing tracks in 1899, was extended to Moshi at Mount Kilimanjaro.Footnote 98 With all this energy being devoted to developing these two lines, von Götzen's road construction scheme was discontinued. Before long, most of the remaining highways fell into a sorry state of neglect.Footnote 99 Only those highways which could serve as feeder roads to the railways were still considered worth maintaining by the government, such as a road from the railway station in Mombo to the town of Lushoto in the Usambara Mountains, on which the colony's first regular motor service with a lorry was inaugurated in 1910.Footnote 100

User engagement with colonial highways

The construction of vehicle-ready highways in German East Africa had begun early on in the German colonial period. But even a decade and a half into colonial rule, little of the ambitious programme had been achieved. By the time the Germans decided to focus on railways instead of cross-country roads, only about 250 kilometres of highways were completed or had at least seen some preliminary works.Footnote 101 Open resistance to labour coercion and the residents’ refusal to maintain roads, as the preceding section has highlighted, were important factors in slowing down the process of colonial spatial appropriation.

If we follow the interviews conducted in Lindi by P. M. Libaba, a member of the Maji Maji Research Project (1968) of the University of Dar es Salaam, opposition to road works was not only the result of unfree labour demands but also because of the alleged purpose of colonial highways. Libaba's interviewees suggested that colonial subjects ‘thought that clearing roads was meant to facilitate the movements of tax collectors whom they hated much. Generally the clearance of roads was understood to make German government effective – more chainings, more beatings, more porterage and everything hateful. So that they hated clearing roads’.Footnote 102 Connected with this perception that colonial roads served colonial travellers are questions of who the roads were built for and who was in fact using them. The remainder of this article engages with the role of road users in the process of colonial infrastructure expansion. Adding to the findings of the previous section, it shows that the agency of local residents was only one reason why the state authorities were unable to make infrastructure durable. As we will see, a second crucial reason was the way many African travellers engaged with colonial roads in their everyday practice — if they engaged with them at all.

German colonisers envisioned that new means of transport would circulate on their roads: pack animals, carts, and potentially automobiles. Beginning under Governor von Liebert, state authorities officially embarked on the quest for a new pack or draught animal.Footnote 103 From 1897 on, several district offices and military stations bred donkeys which they used as riding animals, albeit mostly on a local level.Footnote 104 The government also sponsored several test-drives with ox-wagons, and in 1900 the first regular ox-wagon service (between Dar es Salaam and Kilosa) was planned by the settler Alfred Pfüller.Footnote 105 His business was suspended the following year as soon became apparent ‘that traffic with a light, well-harnessed cart was possible on a good surface. Heavy loads, however, caused the cart to get stuck at the first obstacle and the loads had to be carried on by porters’.Footnote 106 Years later, the first motor vehicles arriving in German East Africa faced a similar fate. In 1907, the German Paul Graetz embarked on a motorised trans-Africa journey. His automobile, however, could not stand the terrain and had to be carried by porters for most of its journey.Footnote 107 Equally unsuccessful was the lorry service between Mombo and Lushoto, which was suspended one year after its inauguration.Footnote 108

While German colonisers dreamed of transferring technology to their colony, the reality was that only a fraction of German East Africa's transport system drew from models introduced by European outsiders. Its predominant characteristics had developed from within the world region. Caravans remained the main users of German East African transportation infrastructure throughout the period under consideration. By the turn of the century, about 100,000 porters continued to arrive every year in the coastal towns at the Indian Ocean.Footnote 109 Although the number of long-distance caravans declined after 1900, owing to a slump in ivory trading, their labour remained in high demand, especially for the booming rubber trade.Footnote 110 In 1907, European observers still estimated the number of caravan porters in the central Tanzanian trade corridor at an annual 40,000 to 60,000 people.Footnote 111

Ignoring the predominance of human-powered mobility, many of the German building efforts under von Liebert and von Götzen broke with established spatial patterns. Even where colonial infrastructure works built on established pathways, the planners corrected road courses to meet the requirements of future vehicle traffic. While caravan trails often ignored slopes and climbed hills straight, for instance, engineers laid out hairpin bends. The opposite was done on many routes running through plains: colonial highways were often planned as straight-lined thoroughfares. District official Karl Charisius, for instance, reported that road works in Tabora ‘generally followed the shortest path according to compass reading…. We did not take [the avoidance of] difficult terrain into consideration’.Footnote 112 Although Charisius insisted that the district authorities had laid out the roads in a way that ‘they touch populated areas at intervals to ensure supply for caravans’,Footnote 113 not all planners did pay attention to established structures and often ignored existing wayside markets and nutrition points for the sake of shortened distances.

How did caravan travellers respond to this attempted departure from the economy of caravan travel? German official Karl Ewerbeck observed in 1900 from the central Tanzanian route corridor that many porters ‘are not grateful for the new barabara because in many cases these roads ignore waterholes and supply of provisions and run through pori [wilderness] simply to shorten distances’.Footnote 114 If we follow the official's observation, African travellers responded to the fractional spatial interventions by avoiding the new roads whenever necessary: the report continued that on the road from Kilimatinde to Mpwapwa, ‘hundreds of porters are seen every day within reach of the two towns. Two days’ march away, however, the barabara is deserted. Instead, caravans prefer two alternative routes running parallel to the barabara’.Footnote 115

Colonial road building complemented vernacular infrastructure, but it did not fully replace it. With a plethora of footpaths still running to every destination, the new infrastructure system had to contend with alternative arrangements running either parallel to or branching off from the new roads. As Ewerbeck's report suggests, it remained the decision of caravan leaders or headmen on which of these different structures to guide their caravans. Traveller's preference of vernacular infrastructure systems was witnessed by German officials and travellers in different parts of German East Africa. Geographer Fritz Jaeger, for instance, noted during his 1906 expedition in northern Tanzania that the barabara between Moshi and Arusha was empty while another route running in the same direction was much-used.Footnote 116 In like vein, Mombo district commissar Max Siegel observed that ‘the natives in the [Usambara] Mountains are far from following the European-style roads because they deem their shenzi [i.e. “wild”] paths sufficient and shorter, and favour them over designed roads’.Footnote 117

Scattered archival evidence suggests that the same holds true for wayside infrastructure. Beginning in 1899, the government made efforts to attach at least some of the new roads in southeastern Tanzania to the needs of caravan travel. To establish artificial marketplaces, district officials forced entire groups to resettle along the new highways.Footnote 118 At these marketplaces, the new settlers either sold their own grain or products provided by the German stations to caravan travellers, who had to pay in rupees, the colonial currency.Footnote 119 The official markets, however, were not the only available supply points as groups residing on nearby caravan trails continued to sell their agricultural surplus to travel parties. Although the available sources do not reveal much information, evidence from the district of Neu-Langenburg (today's Tukuyu) suggests that at least in the region west of Lake Nyasa caravan travellers did not make much use of the German supply facilities. Instead, as a local official observed, ‘porters prefer to buy their provisions cheaper. This method is also applied by the Askaris [African soldiers], who do not buy on the markets but send their boys into the villages, where they could buy foodstuff for half the price compared to the market’.Footnote 120

The result of the outlined disuse of colonial infrastructure by African travellers was that the scattered highways remained prone to collapse. Echoing Gerald Portal's above-cited description of vernacular paths, German officer Georg von Prittwitz und Gaffron observed in 1902 that an important road in southeastern Tanzania, in theory connecting Kilwa with Songea, had vanished again due to insufficient traffic: ‘the old barabara from Songea to Barikiwa is completely overgrown again because it is only used very rarely’.Footnote 121 While the colonial road system depended on political decisions on where and how to invest in roads, rather than on porters voting with their feet, it shows that footwork remained a crucial aspect of infrastructure production: because many villagers and tax defaulters defied their assigned duties to clear the roadways, colonial infrastructure was often only maintained by the people's circulation, without which it could not persist.

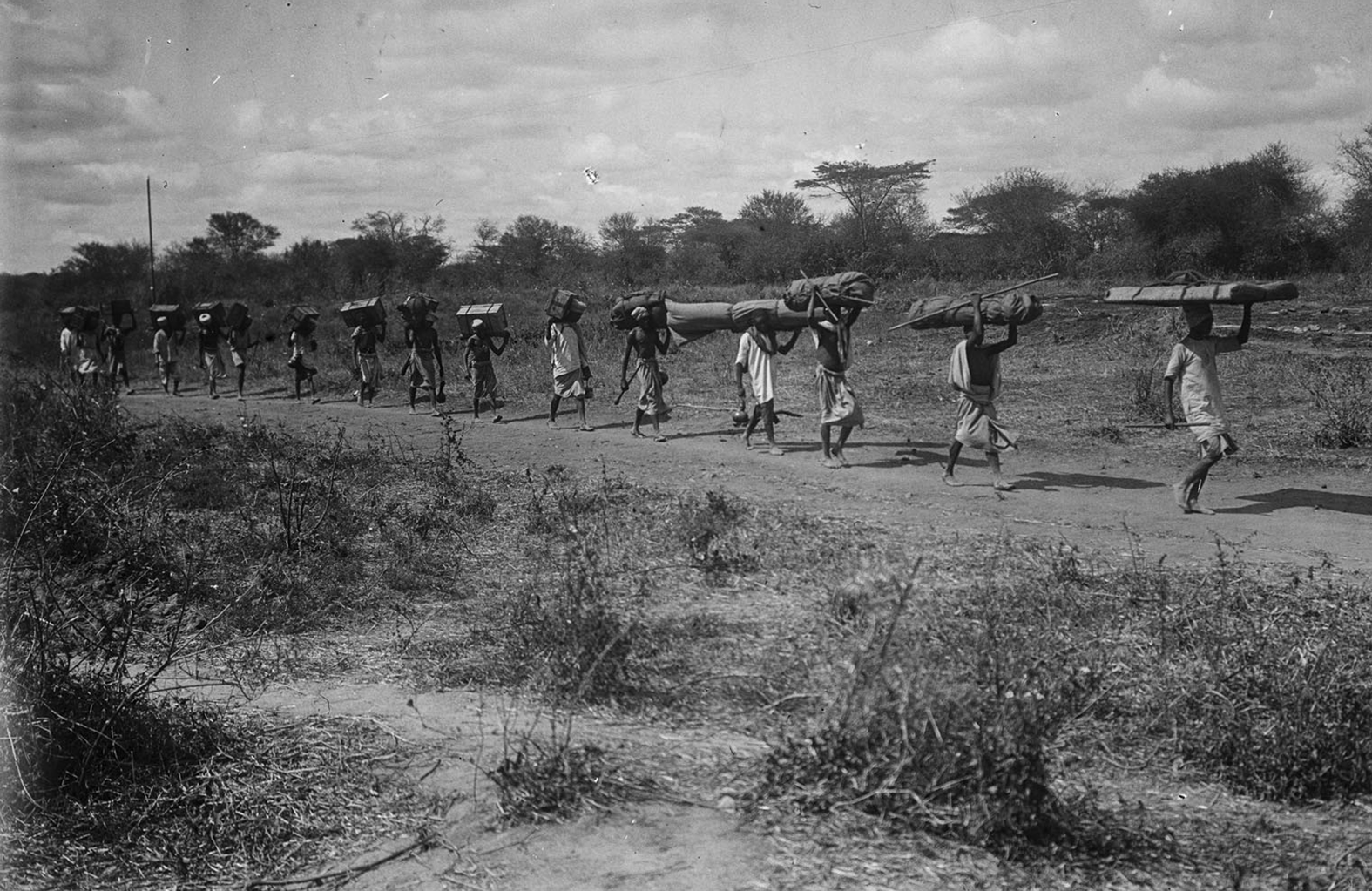

Even where caravans marched on the highways, the movement of these travel parties posed an obstacle to the permanence of colonial infrastructure. Apart from the scattered German stations, no regulatory power could enforce any ‘appropriate’ use of the converted roads. Where colonial road builders had applied hairpin bends to manage the steep slopes of mountain roads, for instance, porters were reported to ‘prefer climbing the hills on [straight] trodden paths instead of following the many hairpin bends of artificially created roads’.Footnote 122 In a similar fashion, the colony's annual report of 1897 complained with regards to the Tabora district that ‘[e]ven though the station as well a number of Sultans [chiefs] have laid out broad roads, the natives do not see any advantage in them and instead march on these roads in one single file’.Footnote 123

Caravan travellers walked on the broadened roadways in the same manner they usually marched on smaller trails (Fig. 3). Because the maintenance of colonial roads depended on movement on them, this behaviour had immediate effects on colonial infrastructure: if they had walked side by side, they would have suppressed vegetation growth across the entire width of the roadway. Retaining a vernacular type of movement, by contrast, accelerated the roads’ decay. This was observed by von Prittwitz und Gaffron in the following year. Travelling with his expedition in the said Tabora district, he remarked in October 1898 that the ‘barabara Tabora–Ujiji [is] a native path, only slightly better trodden than the others’.Footnote 124

Fig. 3. Georg von Prittwitz und Gaffron, ‘Porters’, 8 August 1903.

Source: Saxon State and University Library Dresden, 71794297.

Further evidence of the insistence on known patterns of movement and its effects on colonial roads is provided by Fritz Jaeger, who noted in his field journal that between Moshi and Korogwe ‘the barabara consists of a roadway carved out on six metres in width, in whose centre runs a winding footpath on which the porters march in one single file’.Footnote 125 Soon, complaints were voiced that any efforts to broaden and maintain the highways were thwarted by porters not complying with the physical movement they were supposed to execute. Different state officials recommended methods to actively involve porters in infrastructure maintenance, such as forcing them to march on a broad front or equipping them with axes and hoes. These ideas, however, were discarded as infeasible before long and the problems remained.Footnote 126 Fig. 4, below, depicts the resulting process of decay in an early stage: only the paths meandering along the barabara proved durable because they were used frequently and thus kept free of vegetation while the edges of the roadways often vanished again under grass.

Fig. 4. Hans Meyer, ‘On the trail’, n.d.

Source: Saxon State and University Library Dresden, 71792075.

Conclusion

This article has shed new light on infrastructure development and its limits in German East Africa by focussing on questions of continuity and change in the transition from the precolonial era to colonial rule. In the world of precolonial long-distance trade, groups residing near caravan routes and caravanners marching along them engaged in the production of trails and their adjunct infrastructure. After the colonial takeover, the German administration made road construction an official task. The decision about when, where, and for whom to build infrastructure was taken out of indigenous hands.

And yet, the actor-centred analysis of this article has demonstrated that throughout the period under consideration, colonial infrastructure remained substantially shaped by social interaction and production in day-to-day activities. A focus on those Africans building and maintaining colonial roads (or being expected to do so) and those primarily using them has helped to explain why most of the roads remained short-lived. Further research is required to assess the commonness of these phenomena across German East Africa and to explore regional differences. Still, the variety of regions covered in the presented source material does already suggest that the described responses can be found in all three major route corridors.

A second finding of the article is the persistence of vernacular infrastructure systems, with which the new roads had to coexist and compete. That caravans could ignore colonial roads illustrates that these structures did not possess any power in themselves, nor did they offer any incentives to non-European travellers. Official infrastructural policy sought to channel colonial mobility into spatially-defined segments. Reading the official records against the grain, however, has revealed more than the weak capabilities of the colonial state. The available evidence also shows that East Africans retained their own visions of space and travel. Because there were usually several arrangements to choose from, caravans could instead use the trails they found most suitable. They still based their itineraries on the accessibility of travel routes, the availability of food and water, and economic and social relations existing along the routes. This East African notion of infrastructure as a means of engaging and networking with pathside people stood in stark contrast with the German understanding of infrastructure, especially railways, as an efficient means to shorten distances or connect two distant points.

Vernacular structures and patterns of mobility proved resilient against German rule while the agency of those Africans subjected to colonial space simultaneously subverted its transformation: taken together, this article has demonstrated that colonial infrastructure development (and, through it, spatial appropriation) in the German colony was not a streamlined process, but a contested field in which infrastructure schemes planned from office desks were constrained by and collided with established structures and practices on the ground.

Beyond the East African test case, these findings have at least two wider implications for the ongoing historiographical debate concerning African engagement with technology in the colonial period. First, the preceding analysis contributes to the shift away from an understanding of infrastructure as a tool to dominate colonised societies towards more nuanced interpretations of these systems. Adding to the recent scholarship on African mobility and consumerism, its findings underline that infrastructure and technology were shaped by the spatial practices of their users, their enduring commitment to established patterns of usage, their economic and social motivations and, in general, by fluidity rather than stasis.

Secondly, more than simply adding to the growing body of literature in Science and Technology Studies and the history of technology, this article has challenged the still-vibrant conceptual focus of infrastructure in Africa as a European invention. Although different scholars have recently explored practices of adoption and adaptation by African users, their research often still revolved around imported technologies. Instead pointing to the centrality of vernacular ideas and technologies for colonial infrastructure expansion, this article has explored continuities as much as ruptures and has illuminated that practices of adoption, adaptation, as well as non-compliance were not unilateral. Infrastructure systems in East Africa preceded colonialism, some of them by centuries, with the case under consideration here dating from at least the mid-nineteenth century. Studying the trajectories of these arrangements in depth provides an important step towards reframing the concepts of infrastructure and technology themselves, moving away from their exclusivist European association with seemingly ‘modern’ engineering. As the case of colonial road building in East Africa demonstrates, historians must pay close attention to African actors, as their concepts and activities are at the very centre of the continent's infrastructure history.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Harald Fischer-Tiné, Norman Aselmeyer, Friedrich Ammermann, D. Anca Cretu, Nikolaos Mavropoulos, Alyson Price, as well as The Journal of African History's editors and anonymous reviewers for their many valuable suggestions that significantly improved the article. I would especially like to thank COSTECH for granting me access to the Tanzania National Archives. The research was supported by ETH Zurich and the Max Weber Programme of the European University Institute, Florence.