Introduction

In recent years, following a growing trend towards one-man-one vote (OMOV) systems in candidate and leader selection, there has been increased academic attention to the methods through which parties choose their leaders (Scarrow, Reference Scarrow1999; Le Duc, Reference Le Duc2001; Caul Kittilson and Scarrow, Reference Caul Kittilson, Scarrow, Cain, Dalton and Scarrow2006; Kenig, Reference Kenig2009; Hazan and Rahat, Reference Hazan and Rahat2010; Cross and Katz, Reference Cross and Katz2013; Pilet and Cross, Reference Pilet and Cross2014; Wauters, Reference Wauters2014; Cross and Pilet, Reference Cross and Pilet2015; Kenig et al., Reference Kenig, Rahat, Tuttnauer, Cross and Pilet2015; Vicentini, Reference Vicentini2020). However, there have been considerably fewer studies focused on how and why leadership tenures end (Cross and Blais, Reference Cross and Blais2012; Ennser-Jedenastik and Schumacher, Reference Ennser-Jedenastik, Schumacher, Cross and Pilet2015, Reference Ennser-Jedenastik and Schumacher2021; Gruber et al., Reference Gruber, Cross, Pruysers, Bale, Cross and Pilet2015). This paper is intended to assess precisely whether these two separate moments – namely, the rise and fall of a party leader – may be connected. More specifically, we intend to assess which (if any) characteristics of the selection system, in combination with other conditions such as participation in government and party electoral support, could favour leadership re-selection in office. Thus, we assume that each newly appointed leader is bound to a different fate: persistence or re-election in office vis-à-vis a departure characterized by more or less conflict. Accordingly, we are only indirectly interested in leader longevity, which is normally the dependent variable used by quantitative studies that have dealt with leadership survival over the last few years (Andrews and Jackman, Reference Andrews and Jackman2008; Ennser-Jedenastic and Muller, Reference Ennser-Jedenastik and Muller2015; Ennser-Jedenastic and Schumacher, Reference Ennser-Jedenastik, Schumacher, Cross and Pilet2015, Reference Ennser-Jedenastik and Schumacher2021). Not even the current study is aimed at replicating or updating the findings already provided by the few but fundamental comparative studies on party leadership selection and de-selection (Pilet and Cross, Reference Pilet and Cross2014; Cross and Pilet, Reference Cross and Pilet2015; Sandri et al., Reference Sandri, Seddone and Venturino2015). Rather we rely on a theoretical framework that takes into account a mix of these two different strands of literature (leadership selection and leadership survival) just in order to provide new insights into empirical and comparative research in the field by testing some given expectations (as well as few hypotheses on which scholars still disagree) on the basis of a different methodological approach and following a peculiar idea of causation, which is assumed to be asymmetrical, equi-final, and conjunctural in nature. More specifically, we turn to qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) to look at the different combination of conditions which lead to the outcome (Ragin, Reference Ragin2008; Schneider and Wagemann, Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012), namely the (possible) renewal of the party leadership vis-à-vis a more or less conflicting departure.

Literature review

Even though only one person holds the office of party leader, the number of people who strive to take that position is much larger and this inevitably results in high levels of intra-party competition. Thus, party leaders need to maintain a sufficient level of internal and external support to remain in power (Ennser-Jedenastik and Muller, Reference Ennser-Jedenastik and Muller2015). As well as an elected political official, a party chair is (theoretically) accountable for his/her voters. Accordingly, analysing the methods and the selectorate called on to appoint (or re-appoint) the party leader becomes crucial to understanding his/her career in office. In this regard, Kenig (Reference Kenig2009: 442) argues that ‘although not an integral dimension of party leader selection, the rules regulating the challenge to an incumbent leader are vital to the analysis of leadership selection’. For instance, non-inclusive methods of selection may pose greater obstacles to potential challengers and provide the incumbent party leader with greater resources to influence the decision-making process in his or her favour (Ennser-Jedenastik and Muller, Reference Ennser-Jedenastik and Muller2015). In fact, some studies suggest that leaders chosen by more inclusive methods face greater risks of de-selection (Bueno de Mesquita et al., Reference Bueno de Mesquita, Morrow and Siverson2002; Ennser-Jedenastik and Schumacher, Reference Ennser-Jedenastik, Schumacher, Cross and Pilet2015; Ennser-Jedenastik and Müller, Reference Ennser-Jedenastik, Schumacher, Cross and Pilet2015; Schumacher and Giger, Reference Schumacher and Giger2017; Ennser-Jedenastik and Schumacher, Reference Ennser-Jedenastik and Schumacher2021).

Nonetheless, there are also scholars who suggest that enfranchising ordinary party members can be a deliberate strategy of the party leadership itself to deprive activists and middle level elites of their influence. Thus, the growing intra-party democracy will increase the legitimacy of the party leadership and will contribute to strengthening the leader's position, securing greater organizational autonomy (Mair, Reference Mair, Katz and Mair1994; Sandri and Pauwels, Reference Sandri, Pauwels and Van Haute2011; Ramiro, Reference Ramiro2013). Besides, intra-party democracy may be one of the possible primary goals of a political party, and as such it is likely to drive party change, which may also be linked to a change in party leadership (Harmel and Janda, Reference Harmel and Janda1994; Borz and Janda, Reference Borz and Janda2018). Furthermore, the degree of approval that party leaders receive from their selectorate – even in the absence of an opponent – is indicative of the extent to which they are in danger of being dismissed in the near future (Ennser-Jedenastik and Muller, Reference Ennser-Jedenastik, Schumacher, Cross and Pilet2015). In turn, a contested and competitive race is more likely to be divisive for the party, which may contribute to further enhancing internal factionalism (Ware, Reference Ware1979; Hazan and Rahat, Reference Hazan and Rahat2010; Wichowsky and Niebler, Reference Wichowsky and Niebler2010). Thus, intra-party conflict over leader succession is also likely to hinder leader survival (Bynander and Hart, Reference Bynander and Hart2006).

Still, we also have to consider the difference between leadership races (LRs) intended to select a brand-new party leader and races where one of the candidates (or most of the time the only candidate) is the outgoing party leader. In fact, leaders who came across the hurdle of the first mandate are expected to exert a stronger control on their own party, which means that they are more likely to survive in office in the following years (Ennser-Jedenastik and Muller, Reference Ennser-Jedenastik and Muller2015). However, a party leader cannot stay in office indefinitely, for political but also demographic reasons. In fact, quantitative studies on leadership survival (Andrews and Jackman, Reference Andrews and Jackman2008; Horiuchi et al., Reference Horiuchi, Laing and Hart2015) have demonstrated that younger party leaders tend to stay in office for a longer period compared to older colleagues.

That said, there are many other elements that are likely to affect the rise and fall of party leaders. The first is fairly obvious: a party leader who wants to keep his/her office has to achieve electoral success. In fact, previous research has found that electoral defeat (i.e. losing votes in elections) and being stuck in opposition increase the probability of leader replacement (Andrews and Jackman, Reference Andrews and Jackman2008; Ennser-Jedenastik and Muller, Reference Ennser-Jedenastik and Muller2015). Still, expected performance is as much important as actual performance: leaders who succeed a high performing predecessor risk early departure, because expectations about party performance may be unrealistically high (Horiuchi et al., Reference Horiuchi, Laing and Hart2015; Ennser-Jedenastik and Schumacher Reference Ennser-Jedenastik and Schumacher2021). However, losing and winning elections may have a completely different meaning for mainstream and challenger or niche parties. Similarly, government participation is likely to be beneficial only for leaders of senior government parties, whereas the impact on leaders of challenger parties might go in the opposite direction (Ennser-Jedenastik and Muller, Reference Ennser-Jedenastik and Muller2015). In fact, some parties consider policy purity (or ideology) more important than winning votes or taking government offices (Harmel and Janda, Reference Harmel and Janda1994). In any case, the positive effects of government participation on leader longevity are much stronger than an increase in seat share (Andrews and Jackman, Reference Andrews and Jackman2008). Furthermore, electoral performance effect disappears when parties enter or exit office at the same time, which means that parties may prioritize office achievement over electoral success. As electoral performance only matters for party leader survival when parties do not experience changes in their office status at the same time, opposition party leaders are permanently more at risk of de-selection than leaders of government parties (Ennser-Jedenastik and Schumacher, Reference Ennser-Jedenastik and Schumacher2021).

Research design

Time span and case selection

Our unit of analysis refers to both ‘actual’ LRs (namely, contested races among different candidates) and ‘coronations’ of single candidates (Kenig, Reference Kenig2008) intended to appoint and re-appoint the party chair in four Western European countries (France, Italy, Spain, and Germany) over approximately the last three decades, from the beginning of the 1990s until the present days. The choice of this time span is motivated by the wish to have more homogeneous party systems among the four countries (for instance, bipolarism did not exist in Italy before 1994), but also to encompass different kinds of LRs/coronations by considering a period in which the parties under scrutiny underwent many changes in their leadership selection procedures. This might guarantee a certain balance between non-inclusive procedures of selection and OMOV systems, which cannot be assured if we go too far back in time.

For the sake of clarity, the term ‘party chair’ (excluding interim and transitional chairs) means that the party leader is not necessarily the electoral leader. Although the Anglo-Saxon tradition tends to identify the party leader with the person intended to become Prime Minister if the party achieves that position in a future government (Davis Reference Davis1998; Scarrow Reference Scarrow, Dalton and Wattenberg2000; Gallagher et al., Reference Gallagher, Laver and Mair2001; Le Duc, Reference Le Duc2001; Caul Kittilson and Scarrow, Reference Caul Kittilson, Scarrow, Cain, Dalton and Scarrow2006), in continental and Southern Europe these two figures do not always coincide. Precisely because of this, until a few years ago the comparative literature on leadership selection (Le Duc, Reference Le Duc2001; Cross and Chrysler, Reference Cross, Chrysler, De Bardeleben and Pammett2009; Cross and Blais, Reference Cross and Blais2012) and the first empirical studies on party leadership survival (Andrews and Jackman, Reference Andrews and Jackman2008) tended to focus on Westminster-style systems only. Instead, our aim is just to compare countries in which the concept of party leadership may take different forms: in Italy, Spain, and Germany the overlapping of party chair and electoral leader is common but not automatic (especially, among left and centre-left parties), while in France this distinction is stronger especially among mainstream parties, also because of the different form of government. Conversely, a country such as the UK is not fit for our empirical analysis, as we look at leader de-selection or (re-)selection rather than at leader longevity: our positive outcome, that is, re-selection in office, is normally absent for British parties wherein leaders do not serve for a fixed term. Actually, this is not so true either for French and Italian party chairs, while in Germany and Spain the leader's term is really fixed because the National Party Law requires parties to have congresses to renew the leadership and other internal organs every 2 or 4 years, respectively. However, even though in Italy and France the timing is not clearly defined, parties periodically organize Congresses (normally every 4 or 5 years) at which, among other things, the party leadership is formally renewed or reconfirmed, while this is not the case in the UK (Vicentini, Reference Vicentini2020). Moreover, the British (quasi) two-party system is not particularly suited for our party selection, being basically deprived of ‘relevant’ extreme parties (Sartori, Reference Sartori, Allardt and Rokkan1970) for most of the considered period.

That said, leaving out the UK for the reasons we have just explained, the countries under scrutiny represent the other four largest and most populated Western European countries. Although they are characterized by a great variability in their institutional and political structures, they also show some common political features that make them suitable for our comparative analysis. In fact, in the last three decades and until a few years ago, these countries were characterized by a bipolar system wherein the political competition was articulated around two mainstream (centre-left and centre-right) parties which alternated in power, alone or in coalition with other smaller parties.Footnote 1 More recently, some of these mainstream parties faced a dramatic electoral decline (mainly French PS and Forza Italia, but to a lower extent also PD in Italy, SPD in Germany and Les Republicains in France) because of the unprecedented electoral achievements of pre-existing parties with scarce electoral strength (such as FN and Lega) and/or the emergence of new parties with a significant electoral support: this dismantled the traditional centripetal structure of party competition in the four countries under consideration.

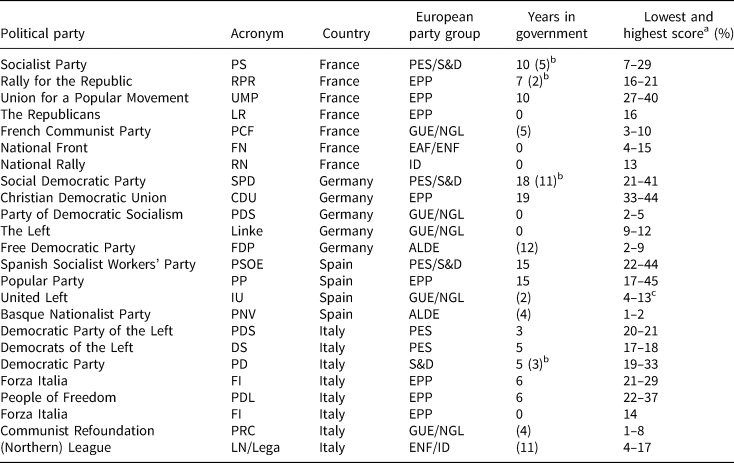

We have selected four parties for each country, both big (in terms of electoral support) mainstream parties and small niche/challenger parties in order to have a quite homogeneous sample in terms of party size and ideology,Footnote 2 as shown in Table 1. For reasons of consistency we decided to focus only on political parties existing for the entire 30-year-period under consideration. Actually, almost half of the parties taken into account has changed its name over the considered period, following merging with other parties and/or serious internal ideological revisions. Yet, no one of them is a brand-new party, as it is the case for some parties which are currently extremely relevant in their own countries: Podemos, En Marche, France Insoumise, M5S, etc.

Table 1. Overview of political parties included in the sample

a Lowest and highest percentage of votes for the party in general/legislative elections from 1990 to 2019.

b The number in brackets refers to additional years in government as minor coalition partner in a grand coalition for SPD and PD. For (mainstream) French parties, the numbers not in brackets refer to years controlling the Presidency of the Republic (and possibly the parliamentary majority), while numbers in brackets refer to years as Prime Minister in cohabitation.

c Since 2016, IU participated in the general elections with a single list in coalition with Podemos.

Source: Authors' own elaboration.

Although the mainstream parties show quite different features in terms of electoral strength and years in government, they normally represent the two most voted parties in each country and they belong to the same European party families (Socialists and Populars). The niche or challenger parties instead tend to include the more extreme left-wing and right-wing forces represented in the national parliament, although showing changing electoral fortunes, different internal characteristics and ‘coalition potential’ (Sartori, Reference Sartori, Allardt and Rokkan1970). Yet, this is not the case in Germany and Spain, wherein the extreme right was not able to get parliamentary seats until very recently (thanks to the electoral successes of AfD in Germany and Vox in Spain). Accordingly, we decided to include a centre party such as FDP for Germany, while in the case of Spain we had to look to regional parties and we selected the PNV, which also has a moderate centre-right orientation.

Specification of the theoretical model: hypotheses and methods

On the basis of the literature review discussed above, we identified five main conditions which are likely to affect the outcome (namely re-selection in office vis-à-vis de-selection/departure), both alone and in combination with each other: whether there is an outgoing leader running for re-election (incumbency); broad inclusiveness of the LR called to appoint the party leader; large victory (namely, low competitiveness in contested LRs or high approval rates in coronations of a single candidate); participation in government during the leadership tenure; and party electoral support during tenure (big mainstream vs. small niche/challenger party). We are aware that there are a number of other potential conditions that may be considered (leader personality, institutional context, external events, etc.). However, it is not worth to include too many conditions in QCA.Footnote 3 Moreover, in order to construct our dataset and calibrate casual conditions and the outcome, we had a detailed preliminary qualitative investigation of all the considered empirical cases.Footnote 4 This allows us to complement our QCA findings with qualitative reflections concerning other specific factors that may have affected LRs, especially in order to explain possible deviant cases.

We do not have clear expectations on whether the above-mentioned conditions are necessary and/or sufficient for the outcome. Yet, according to the literature presented in the second section, we can derive some theoretical hypotheses regarding the relations between conditions and the outcome and among conditions themselves: although scholars do not agree on whether an inclusive process of selection favours or hinders leaders' reappointment, we expect leaders who came across the hurdle of the first mandate to exert a stronger control on their own party, which means that they are more likely to be reconfirmed in office in the following years, although a party leader cannot stay in office indefinitely. Furthermore, when LRs are more competitive, it might indicate that parties are more internally fragmented, and therefore the office of party leader is more at stake. Similarly, even in the absence of an opponent, we expect a party leader selected or re-selected with a low approval rate to be more in danger of being dismissed in the near future (Ennser-Jedenastik and Muller, Reference Ennser-Jedenastik and Muller2015). Still, the relation between government participation and leader re-selection/de-selection is not straightforward. In fact, we assume that, regardless of electoral performance, a leader of a big mainstream office-seeking governing party is less likely to be removed from his/her party office, notably if he/she is simultaneously the head of government, but this is not true in the case of smaller (challenger) parties, which may have different party goals (Harmel and Janda, Reference Harmel and Janda1994).

All these things considered, in QCA terms we assume that the combination of presence in government and whether the party is a big one in terms of electoral support and, in a specular way, the combination of absence in government and whether the party is a small one in terms of electoral support, as well as incumbency, on the one hand, and large victory once originally appointed, on the other, should contribute to the outcome when present; on the contrary, we do not have a clear hypothesis concerning the role of broad inclusiveness of the selectorate for leaders' re-selection (Sandri and Pauwels, Reference Sandri, Pauwels and Van Haute2011; Ennser-Jedenastik and Schumacher, Reference Ennser-Jedenastik, Schumacher, Cross and Pilet2015; Schmacher and Giger, Reference Schumacher and Giger2017). Overall, our expectations can be read in terms of necessity and/or sufficiency: the combination of presence in government and large party electoral support is sufficient for the party leader to be re-selected (H1); the combination of absence in government and limited party electoral support is sufficient for the party leader to be re-selected (H2); incumbency is sufficient for the party leader to be re-selected (H3); a large victory when originally appointed is sufficient for the party leader to be re-selected (H4). Furthermore, these theoretical hypotheses identify causal relations which are assumed to be asymmetrical,Footnote 5 equi-final,Footnote 6 and conjunctural.Footnote 7 All this makes clearer the decision to conduct our empirical analysis through QCA. In fact, asymmetry, together with equi-finality and conjunctural causation, is one of the main characteristics underpinning the idea of causality in configurational studies (Schneider and Wagemann, Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012), among which QCA is probably the most developed, utilized and known (Rihoux et al., Reference Rihoux, Alamos-Concha, Bol, Marx and Rezsöhazy2013).

Specification of the theoretical model: operationalization and calibration

The first causal condition is easily explained: as well as a member of Parliament who run for re-election in his/her own constituency, we call ‘incumbency’ the condition wherein the outgoing leader re-run for the party office either against other candidates or, more frequently, in coronations. Of course, in case of contested races, it is not taken for granted that ‘incumbent’ party leaders will be actually reconfirmed in office. Theoretically, this is not the case for party congresses with a single candidate either, as there might be a threshold to be reached (normally 50%). Yet, not reconfirming an incumbent leader in a coronation is a very unlikely possibility.

As for the other four conditions and the outcome itself, here we simply point out the indicator(s) that we used for the operationalization, referring to the online Supplementary material for a careful discussion and justification of all the choices we made in the process of ‘calibrating’ the sets (Ragin, Reference Ragin2008; Schneider and Wagemann, Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012).

According to the literature on leadership selection, the main indicator for assessing LR inclusiveness is the type (and size) of the selectorate, that is, the group of people called on to choose the party leader. Scholars usually consider six ‘pure' types of selectorates, ranked from the most to the least inclusive (Kenig, Reference Kenig2009; Pilet and Cross, Reference Pilet and Cross2014; Spies and Kaiser, Reference Spies and Kaiser2014; Kenig et al., Reference Kenig, Rahat, Tuttnauer, Cross and Pilet2015): electorate (open primaries), membership (closed primaries), party delegates, party council, party parliamentary group or party top organs, and party leader. Yet, different kind of mixed selectorates (voting simultaneously or in different steps) are also possible. Nonetheless, a huge selectorate may also be called on to vote in order to certify the top-down appointment of a single candidate. In this case it is quite clear that the inclusiveness of the selectorate is largely irrelevant, as the party oligarchy maintains all its decision-making power in the process of leadership selection. Accordingly – as the ‘inclusiveness’ condition is intended to capture the level of intra-party democracy in the process of leadership selection – a ‘coronation’ by a middle/large selectorate (i.e. party members) cannot be considered an inclusive LR (even because, actually, it is not even a ‘real race’). Accordingly, with the selectorate being equal, a contested race is assumed to be more inclusive than a coronation. Thus, we order and classify the level of inclusiveness of our empirical cases on the basis of a seven-point scale, ranging from the lowest level of inclusiveness (coronations wherein the party chair is chosen by the party elite or even by the outgoing or founding leader, or is self-proclaimed) to the highest level (contested open primaries).

Moving to the third condition, it is worth recalling that the literature on primary elections and OMOV systems has estimated competitiveness in several different ways: through dichotomous (Hacker, Reference Hacker1965; Bernstein, Reference Bernstein1977) or metrical variables (Piereson and Smith, Reference Piereson and Smith1975; Grau, Reference Grau1981); or using only the results of the winner, of the two most voted candidates, or of all the competitors (Atkeson, Reference Atkeson1998; Kenig Reference Kenig2008). On this, we opted for a simple ordinal scale: very competitive, somewhat competitive, barely competitive, not at all competitive. The lower the LR competitiveness, the larger the winning margin. A similar criterion has been applied for measuring the winning margin of a single candidate: we assume a 90% approval as the threshold between a (somewhat or very) large victory for the newly elected or reappointed leader and a (somewhat or very) disappointing result which may indicate a certain level of internal opposition.

As far as participation in government is concerned, first we distinguish between chairs whose party was mostly in government during the leadership tenure and chairs whose party was mostly in opposition during tenure. Moreover, we also distinguish between party leaders who personally serve as head of government and party leaders who lead their governing party from the outside (or perhaps hold some other executive positions but not the ‘main’ one). Keeping these two criteria together we came up with a five-point scale, on which the lowest point is represented by leaders whose party was always in opposition during tenure and the highest point refers to party leaders who were also heads of government.

As for the last condition, namely party electoral support, we simply looked at vote percentage in the closest general/legislative election in the course of the leadership tenure. Accordingly, we looked at electoral results for the 16 political parties under scrutiny in the 30-year-period considered taking into account the proportional vote in case of mixed electoral systems and the first turn of vote in the case of France.

Finally, we need to explain the operationalization of the outcome. As Kenig (Reference Kenig2009: 442) points out, it is quite unlikely today to have an unlimited leadership mandate because of ‘the democratic norms of accountability and competitiveness’. Most of the times the end of the tenure does not depend on specific rules, but simply on indirect internal negotiations or pressures that force the party chair to leave the office in advance. Yet, most party leaders are periodically submitted to some forms of verification/reappointment, generally through party congresses. Thus, reappointment in office represents the most ‘positive’ outcome for a party leader, which we assume to be ‘qualitatively’ different from any kind of departure, voluntary or not. That said, the literature suggests that reasons for departure can be divided into five categories, ranging from the one showing the lowest level of conflict between the outgoing leader and his/her party to the highest level of conflict (Cross and Blais, Reference Cross and Blais2012; Gruber et al., Reference Gruber, Cross, Pruysers, Bale, Cross and Pilet2015). These are, respectively: force majeure, voluntary resignation, post-election resignation, resignation under pressure, and formal removal.

The first category refers to cases where the party leader dies or the party disappears, but it may also include problems of incompatibility between the role of party chair and other offices. In this case we don't know what would have happened otherwise: maybe the party leader would have been re-selected in the subsequent LR, maybe not.

Thereafter, we have three distinct types of resignation. The first is the truly voluntary resignation in which the leader autonomously decides to leave, possibly after a long run in office and after having served as chief executive. This means that the leader could remain in office if he/she had wanted to, but it may also hide some internal tensions. The second category encompasses what has been said before concerning the relation between leadership survival and electoral failure. Here, we consider resignations that occur within 1 month after an election with ‘national value’, namely general and European elections. Moreover, even though they are not proper ‘elections’, we may also include national referenda in this category. The third type (resignation under pressure) includes the cases where there was a broad, organized movement calling on the incumbent to resign from the leadership (Pilet and Cross, Reference Pilet and Cross2014), regardless of a negative electoral outcome, although the two things are often interlinked. In fact, the different timing does not seriously change the essence of the resignation, which has to be ascribed to the loss of support from the public opinion and/or the party core. Thus, scholars generally prefer to collapse these two categories into a single one (Gruber et al., Reference Gruber, Cross, Pruysers, Bale, Cross and Pilet2015).

To conclude, the ‘formal removal’ category originally referred to a specific instrument through which a top party organ votes against the leader to remove him/her from office. This instrument is typical of Westminster systems. However, the literature also includes cases in which the outgoing leader is formally challenged and defeated by other contenders at the end of a (more or less defined) fixed term, for instance in a party congress. This is exactly the definition that we adopted, and from this point of view, formal removal (or de-selection) is just the opposite of re-selection.

Descriptive statistics

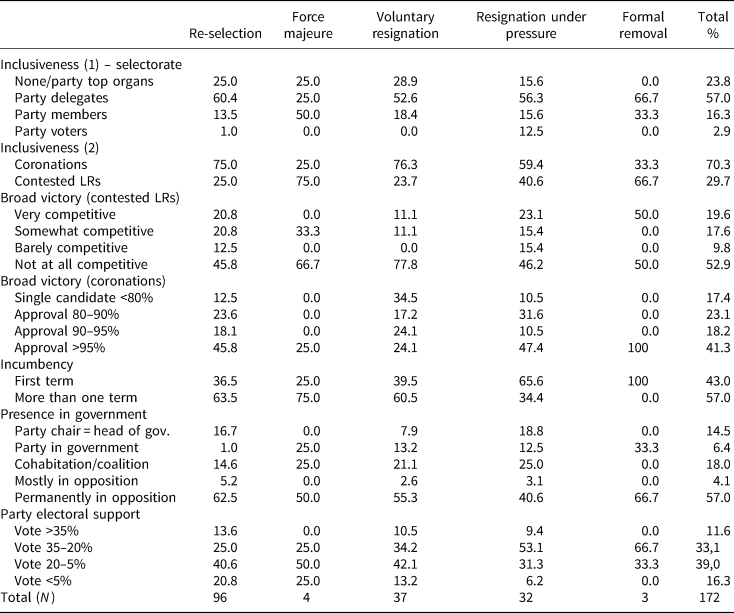

Our sample includes 172 LRs/coronations accounting for both the party leader's first appointment in office and all the reappointments at the end of the term. As shown in Table 2, about one-third of the party leaders in our sample were not re-elected. Among those who were successfully reappointed, the majority completed three or more terms in office. This confirms that once the hurdle of the first mandate is overcome, party leaders are generally more likely to be reappointed in office.

Table 2. Party leaders' reappointments and reasons for departure (column %)

When a formal vote for the single contender is required (as happened in all cases except for Berlusconi in Italy and Jean Marie Le Pen in France, who used to be reappointed by acclamation), leaders' approval rates generally reach 90% or more, but about 40% coronations ended with lower percentages, which may be a sign of a split within the party. In turn, the likelihood to have coronations decreases as the inclusiveness of the selectorate increases. In fact, the data confirm that while large selectorates are very rarely called on to vote for a single candidate, closed and open primary elections are much more likely to host more than two candidates, even though this does not always translate into highly competitive contests. In fact, Kenig et al. (Reference Kenig, Rahat, Tuttnauer, Cross and Pilet2015: 50) have already demonstrated that ‘competition for party leadership, and especially close competition, is the exception rather than the rule’.

Interestingly, the party leadership of ‘small’ parties is often more stable than the leadership of ‘big’ parties, maybe because they are less subjected to the effect of electoral swings and there is also less internal competition to become party chair, as the leader has less resources to distribute (for instance, in terms of government offices). Moreover, especially for radical parties, the preference for a strong and durable ‘charismatic’ leadership may also be a matter of political culture: while historically rightist forces tend to be more leadership-dominated (Schumacher and Giger, Reference Schumacher and Giger2017), the parties coming from a communist tradition also tend to disregard challenges to the dominant coalition.

As far as the reasons for departure are concerned, there are only six cases of party leaders who comes to an end because of force majeure or formal removal, while ‘voluntary resignations’ and ‘post-election/under pressure resignations’ represent the most populated categories. The latter category also includes some long-lasting leaders who completed more than two terms as party chairs and who were expected to leave their office in ways less marked by ‘conflict’ (Kohl, Zapatero, Rajoy, Bossi, Westerwelle, etc.). In this regard, it is important to notice that all but one of the longest-serving leaders of mainstream (big) parties also served as chief executive during most or part of their (party) mandate. By contrast, the case of François Hollande is rather peculiar: during his four terms as PS First Secretary he did not have any governmental position and the Socialists suffered many severe electoral defeats, yet he was the French (major) party leader with the highest number of consecutive reappointments in office over the last few decades. There is also the case of a party leader (Mariano Rajoy) who was electorally unsuccessful for almost a decade (as he also ran twice as chief executive candidate) but was still able to be reconfirmed in his party office in 2008, until his electoral fortunes changed and he finally won a general election, securing a successive reappointment as party leader in 2012. Rajoy's case also contradicts what is maintained by Horiuchi et al. (Reference Horiuchi, Laing and Hart2015), who suggest that successor(s) of long-serving party leaders – and/or of leaders who had also been the head of government (namely, Aznar) – have lower longevity than others. However, this hypothesis has in fact been partially confirmed by the short mandate of Schäuble and Rubalcaba, Kohl and Zapatero's successors respectively.

As far as cross-national differences are concerned, Spanish party leaders seem to be reappointed more often than their Italian and French counterparts. However, the number of reappointments also depends on party customs or country law. Concerning this it is not surprising that the record in recent time is up to Angela Merkel – who has been formally reappointed eight times – just because German Party Law requires each party to hold a Congress every 2 years, while in the other considered countries party congresses are celebrated less frequently. Instead, French leaders of both centre-right and centre-left mainstream parties are the most unstable in their positions, while this is not the case for the PCF and (especially) FN. This probably depends on the stronger separation between the party chair and the role of electoral leader, president of the Republic or Prime Minister. In this regard, the different institutional context (namely, the French semi-presidential system vis-à-vis the parliamentary system that characterizes the other three countries under scrutiny) has probably played a role. In fact, it is interestingly to notice that radical parties' chairs are more likely to run as presidential candidates (in spite of having no chances to win) than the party chairs of the mainstream parties. Moreover, it is hard to find very clear differences in the leadership path of PS and RPR/UMP/LR chairs serving during periods of government and those serving during periods of opposition. Finally, Italy and Germany are the countries showing the greatest distance between the two mainstream parties: centre-left party chairs are traditionally weak and (relatively) short-term (both SPD and PDS/DS/PD changed about a dozen leaders in the 30-year-period considered), while the centre-right leadership is much more stable.Footnote 8 Instead, smaller parties in the two countries show quite stable leadership (ranging from three to six different chairs over the last 30 years), regardless of the ideological positioning.

Exploring the determinants of party leaders' re-selection

We now return to fuzzy-set QCAFootnote 9 to explore empirically the combinations of conditions that might contribute to explaining whether and how a party leader is reconfirmed in office or forced to resign. This section presents the main results of our empirical analysis in terms of both the need for and sufficiency of relations between conditions and the outcome.

The analysis of necessary conditions for leader reappointment shows that no condition (or its non-occurrence) was necessary for the outcome (or for its non-occurrence).Footnote 10 As for the analysis of the sufficient conditions for being reconfirmed as a party leader, see Table 3 presenting solutions terms, consistency, coverage, and cases covered of the intermediate solution, which is as follows:

Table 3. Intermediate solution: solution terms, consistency, coverage, and cases covered

Intermediate solution coverage (proportion of membership explained by all paths identified): 0.919833.

Intermediate solution consistency (‘how closely a perfect subset relation is approximated’) (Ragin, Reference Ragin2008: 44): 0.771619.

Raw coverage: proportion of memberships in the outcome explained by a single path.

Unique coverage: ‘proportion of memberships in the outcome explained solely by each individual solution term’ (Ragin, Reference Ragin2008: 86).

Empirically contradictory cases are shown in bold.

Parsimonious solution: Incumbency + ~Government*~Big party + Large victory*~Government + Government*Broad inclusiveness*~Large victory (consistency 0.77; coverage 0.92).

Complex solution: Incumbency*~Broad inclusiveness + Large victory*~Government + ~Broad inclusiveness*~Government*~Big party + Incumbency*Government*Big party + Broad inclusiveness*Government*~Incumbency*~Big party + Large victory*Incumbency + Large victory*Broad inclusiveness*~Big party (consistency 0.78; coverage 0.86).

Intermediate solution: Incumbency + ~Government*~Big party + Large victory*~Government + Broad inclusiveness*~Big party

Theoretically, the (intermediate) solution above means that re-selection in office is associated with four different combinations of conditions: first, incumbency alone favours leadership re-selection. This solution term confirms previous theoretical expectations, as outgoing leaders who run for a new term are supposed to exert a stronger control on party internal dynamics and are provided with more resources to be distributed within the organization in order to maintain the power. However, as we have already mentioned in the literature review and in the theoretical part, this kind of advantage for outgoing leaders is bound to extinguish progressively after many years in office. In fact, this consideration seems to explain most of the deviant cases characterizing this first solution, as more than 60% of them refer to the last mandate of long-serving party leaders – namely leaders who have been reappointed in office several times – who, in the case of big parties, were also heads of government.

Moreover, party leaders' re-selection is also linked to a combination of absence from government and limited party electoral support. This solution term is also in line with theoretical expectations: government participation is not beneficial for challenger or niche parties.

Third, leadership re-selection is apparently favoured by the absence of government responsibilities counterbalanced by a large victory once elected as party leader. The interpretation of this solution term is less straightforward. In fact, the previous solution term suggested that government participation is not beneficial for small parties, but we do not expect the same for mainstream parties. However, looking at the empirical cases explained by this solution term helps us to venture a first interpretation, that may be interesting to test in future studies. In fact, most LRs presenting the aforementioned conditions and the expected outcome (re-selection) refer to the first and second appointment of future long-standing leaders. The fact they had large victories may suggest that, from the very beginning, the party establishment and/or the party grassroots have seen not common ‘leadership skills’ in these brand-new candidates. Therefore, on the one hand, not surprisingly, these ‘leadership skills’ and the usual condition of opposition parties favour the reappointment of small party chairs. On the other hand, the lack of government responsibilities was not harmful for future long-standing leaders of mainstream parties such as Aznar, Rajoy, and Hollande, just because they already counted on a huge support within the party organization, as shown by the large victories obtained at the moment of their appointment. In this regard, the analysis of deviant cases provides some further confirmation of this hint: although the PD leaders Franceschini and Martina were both elected with high percentages, they were not reconfirmed in office at the end of the term, both losing the successive primary elections. The reasons for that may rest both in the lack of the above-mentioned ‘leadership skills’ and in the fact that their appointments as party chairs were much less successful than how it seems just looking to the percentage they have obtained. In fact, both were elected by the PD National Assembly – although open primary elections were already become the ‘normal mode’ of leadership selection within the party – just following the forced resignation of the previous party chairs. In this regard, their leadership was largely transitional (in view of the successive ‘real’ leadership selection by open primaries), and the high percentage obtained simply reflected the lack of valid alternative candidates and the necessity for a very fragmented party to show a certain unity in such a delicate moment.

Finally, the logical minimization of the truth table shows that party leaders of small parties elected through an inclusive LR have chances to be reappointed in office. Actually, this solution only explains four empirical cases which are actually quite peculiar. In fact, they do not refer to leaders of niche parties, but to leaders of mainstream parties which were facing a loss of votes in that particular moment. In fact, the adoption of inclusive procedures of selection is more likely in moments of crisis, just because they can contribute to legitimizing the party leader in the eyes of the public.

Both the consistency value (0.77) and (in particular) the coverage (0.92) of the intermediate solution are satisfactory. However, there are 38 empirically contradictory cases, meaning that they are ‘more in than out’ of the set of ‘party leaders expected to be re-selected’, but ‘more out than in’ of the set in which it should have been included. An overwhelming majority of those empirically contradictory cases can be explained taking into account the ‘deterioration’ of long-serving leaders we mentioned above. The others have all peculiar motivations linked to contextual elements and/or lack of ‘leadership skills’, as we explained more in details in the online Supplementary appendix.

In any case, 97 cases are explained by any (i.e. one or more) of the four equi-final solution terms: in other words, following Schneider and Rohlfing's (Reference Schneider and Rohlfing2013: 585) terminology, they are ‘typical cases’. Moreover, four further cases (Fassino3, namely Fassino's third and last term as DS chair, as well as Anguita1, Urkullu2, and Alliot-Marie) can be considered to represent good instances of any of the four solution terms and of the outcome; in fact, even though their membership scores in the final solution set are higher than their membership scores in the outcome set, they still are ‘more in than out’ the set where they should have been. Finally, although the 25 cases that are not good examples of either the solution terms or of the outcome do not merit particular attention, the eight so-called ‘deviant cases for coverage’ (the first appointment in office of Zapatero, Veltroni, Schröder, Hollande, Gerhardt, Séguin, Berlusconi, and Casado Blanco) are much more interesting: indeed, they were not expected to stay in office, but did so nevertheless. As with the previous empirically contradictory cases, they also merit further investigation.

The case of Zapatero might be explained on the basis of the dramatic events that occurred in Spain just before the 2004 general elections. In fact, the conditions of Zapatero's unexpected first election as PSOE chair (in an extremely competitive LR, when the PP was firmly in power and he was still very young and largely unknown) would have foreshadowed a forced resignation as a consequence of the subsequent electoral defeat, which was in fact anticipated by the polls. However, the misconceived management of the aftermath of the terrorist attack by the outgoing Popular government provoked an unprecedented electoral upset which caused the precariously newly elected party leader to become the new Spanish Prime Minister (Bali, Reference Bali2007). The case of Silvio Berlusconi is absolutely unique: as he was the founder and to a large extent the master of his own party, an early resignation was almost unconceivable, regardless of the combination of conditions that we proposed. As for Hollande, we have already claimed that he represents a somewhat peculiar case, being the French (major) party leader more frequently reappointed over the last few decades notwithstanding the lack of any governmental position and the facing of severe electoral defeats during his four terms as PS First Secretary. As we claimed in the descriptive section, this is probably also linked to the influence of the semi-presidential system, wherein the link between government responsibilities and party leadership of mainstream parties is apparently weaker compared to the other parliamentary systems considered. Veltroni and Séguin's first mandate was a kind of ‘halved mandate’, so the successive reconfirmation in office was rather expected. In fact, just a few months after Séguin's first appointment to office in 1997, the RPR adopted a new and more inclusive procedure to elect the party leader. As a consequence, just a year and a half after his first election by party executives, he was re-appointed, uncontested, by the whole party membership. Instead, Veltroni became the new DS party chair at the end of 1998 in order to replace the former chair D'Alema, who had just been nominated Prime Minister, but he was officially reconfirmed in office at the beginning of 2000 at the first DS congress. Finally, although Casado Blanco's appointment as party leader of the Popular Party in Spain is very recentFootnote 11 and time will say whether he will be re-selected or de-selected from his chair, the explanation for the case of Wolfgang Gerhardt (leader of the FDP in Germany from 1995 until 2001) is not straightforward. However, he resigned (under pressure) after he concluded his third term in office, which means that a (slight) ‘deterioration’ may have played a role, even if in Germany three terms means that Gerhardt's leadership only lasted for 6 years.

Concluding remarks

In this paper, we have employed QCA in order to explore which (combinations of) conditions could favour party leader reappointment in office. We identified four different combinations of conditions: incumbency; small party electoral support and absence from government; absence from government counterbalanced by a large victory once elected as party leader; and inclusive procedure of selection and limited party electoral support. As expected, these findings confirm that leaders who already served for one or more party mandates are more likely to be reconfirmed in office. The characteristics of the LR appear to be less important for the outcome: our combinations confirm that the assumed legitimization that may be associated with an inclusive process of selection alone does not guarantee re-selection. At the same time, being in opposition is not necessarily an obstructing condition for leader's reappointment, especially in case of a broad success in the previous LR which is generally (but not always) a mirror of party unity and convinced support for a candidate with particular ‘leadership skills’. Still, this does not support the quite widespread concern that (potentially divisive) primary elections and OMOV systems are destructive for party cohesion, as the findings do not suggest that an inclusive LR possibly ending with a narrow victory will lead to a more or less conflicting departure. All these things considered, our empirical analysis demonstrates the importance to focus on the combined effect of different conditions to assess leadership re-selection and de-selection in comparative perspective, but it also suggests caution in making generalized inferences. Accordingly, this novel methodological approach is mainly intended to inspire different paths for future research.

The first path concerns a qualitative in-depth analysis of the contradictory and deviant cases that emerged from our QCA (and that we just sketch in our online Supplementary appendix), in order to better understand country and party peculiarities, but also the specific idiosyncratic characteristics of the LRs. The second path would be to include further conditions in our theoretical framework. For instance, the empirical analysis and the qualitative evaluation of deviant cases suggest the importance of considering the concept of ‘deterioration’ for leader departure, as well as that of external and unpredictable factors. Moreover, a specific condition dealing with intra-party fragmentation (which was only indirectly touched by the ‘large victory’ condition in the LR) may be introduced as well. Finally, electoral success would be another condition to be considered.

This brings us to the third possible path: enlarging the number of empirical cases in terms of both parties – also considering some brand-new parties which have become extremely relevant in their own countries in the last few years, such as Podemos, En Marche, France Insoumise, M5S, etc. – and countries considered, even beyond the borders of Western Europe. This would guarantee larger variability but, at the same time, it would help us constructing a more balanced sample for both our conditions and the outcome. In fact, our sample was partly skewed by the prevalence of uncontested party congresses to appoint party chairs, while the ‘formal removal’ or ‘force majeure’ categories were largely underrepresented among the reasons why party leaders leave their offices. Still, it would be interesting to try to replicate this study just considering a slightly different sample, in order to see whether our solution terms hold or not.

Finally, we think that our theoretical and methodological approach could be also effectively employed to explore different aspects related to the study of party leadership and intra-party democracy. For instance, QCA may provide a new analytical perspective for the increasing number of studies dealing with the consequences of greater inclusiveness in leadership selection in terms of both party cohesion and electoral performance.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2021.6.

Funding

The research received no grants from public, commercial, or non-profit funding agency.

Data

The replication dataset is available at http://thedata.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/ipsr-risp.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers who very much helped us to improve the paper.

Conflict of interest

None.