Introduction

In the wake of the 2015 ‘Islam Law’, which bans the foreign funding of religious groups and requires imams to speak German,Footnote 1 the Austrian government closed seven mosques in June 2018 and declared that up to 40 imams face the possibility of losing their residence permit. The decision followed an investigation into activities conducted by mosques and reports about children wearing uniforms and waving Turkish flags while re-enacting the First World War's Battle of Gallipoli in a Turkey-financed mosque in Vienna. How do states exert power over members of their societies living outside their borders? What does the re-enactment of the Battle of Gallipoli by children attending Islamic courses in Vienna reveal about how Turkey governs a section of its ‘domestic abroad’ (Varadarajan, Reference Varadarajan2010)?

A vast amount of literature focuses on states' engagement in constructing ‘diasporas as subjects of an expanded, territorially diffused nation’ (Varadarajan, Reference Varadarajan2010: 6). To date, scholars have focused on ad hoc institutions, policies, and the bureaucratic apparatuses through which nation-states maintain political, economic, and religious ties with their respective communities abroad (Waldinger and Fitzgerald, Reference Waldinger and Fitzgerald2004; Varadarajan, Reference Varadarajan2010; Délano and Gamlen, Reference Délano and Gamlen2014; Adamson, Reference Adamson2019; Gamlen et al., Reference Gamlen, Cummings and Vaaler2019). According to Gamlen, state engagement in diaspora policies ‘(re)produce citizens-sovereign relationships with expatriates, thus transnationalising governmentality’ (Gamlen, Reference Gamlen2006: 5; Gamlen, Reference Gamlen2014). Therefore, governmentality – that is, the multiplicity of ‘discourses and meanings that construct, maintain and transform ruling’ (Bevir, Reference Bevir2011: 457–458) – makes it possible to assess the multiple techniques that the origin states employ to extend control beyond their territorial boundaries and turn the diaspora into a governable subjects (Ragazzi, Reference Ragazzi2009).

This article investigates what the activities conducted by religious officers sent abroad reveal about Turkey's current art of governing its diaspora. It draws on pastoral power, which is a particular governmental technique that Foucault defines as the: ‘art of governing men’ (Foucault, Reference Foucault2009: 165). The pastors exert a role between guidance and care; they cater to individuals' needs with the intention of reaching the whole flock. Elaborating on Foucault's 1977–78 conceptualization, Martin and Waring recently operationalized and defined pastoral power in relation to governmentality: ‘Pastoral power might be one means whereby the connection between governmental discourses and the constitution of subjects is effected – through the embodied, empirically visible agency of pastoral actors in concrete relationships of power with one another, not through some neglected, invisible, yet apparently all-encompassing discursive power’ (Martin and Waring, Reference Martin and Waring2018: 1298). The present article contends that imams and preachers embody and concretely implement pastoral power as a governmental technique aimed at building loyal and enduring relations with the emigrants while translating and propagating the government's discourse abroad. In this respect, religious officers sent to Austria allow us to rethink Turkey's engagement with its diaspora as part of its art of governing (Aymes et al., Reference Aymes, Gourisse and Massicard2014). The article's main finding is that, through the Diyanet, Turkey acts as a caregiver and a services provider that paternalistically embraces its dispersed communities while forging them as loyal and disciplined subjects.

Imams, preachers, and Qur'an teachers sent from Turkey to Austria are civil servants (din görevlisi) employed by the Presidency of Religious Affairs (hereinafter, Diyanet), a state agency established in 1924. In its capacity as one of the emblems of Turkish laicism (laiklik), the Diyanet manages and controls religious affairs, supervises Turkish mosques, employs religious officers, and develops and spreads the Turkish version of the Sunni Hanafi Islamic doctrine (Kuru, Reference Kuru2007; Gözaydın, Reference Gözaydın2008).

After presenting the methodological and analytic framework, the article illustrates the theoretical contribution of pastoral power to the study of diaspora governance. The analysis then focuses on how religious officers' discourse and practices help to translate and convey the religious conservative and nationalist ideology of the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, AKP) to the Turkish diaspora communities (White, Reference White2013). The three sections of the analysis focus on the activities of imams and preachers sent to Diyanet mosques in Europe (Demir, Reference Demir2010; Bruce, Reference Bruce2020) and outline (i) how Diyanet officers' pastoral practices go beyond the mosques and manifest in a wide range of socio-cultural religious services aimed at reaching diaspora communities, (ii) how Diyanet officers' activities relate to the Turkish state's extraterritorial practices and discourse aimed at promoting obedience to the authorities and love for the motherland, and (iii) how the interaction between Diyanet officers and the flock shape people's perception of themselves as a community while remapping the boundaries of a Turkish and Muslim belonging in essentialist terms.

Discourse, practices, and micro-approach: methodological premises and theoretical framework

This article examines Turkey's extraterritorial practices aimed to reach and govern its diaspora communities living in Austria. The Austrian case is important for several reasons. First, the composition of the immigrant population is particularly relevant: According to 2019 statistics, out of a total population of about 8 million, some 2 million (23%) are people whose parents were both born abroad. Specifically, about 570,000 are Muslims, with TurksFootnote 2 taking the largest share of this group: 271,000 Austrians have a Turkish background.Footnote 3 Secondly, Muslim associations in Austria have a long tradition dating back to much earlier than the establishment of representative bodies in the 1990s in many European countries. In her study conducted in 2009, Zana Çitak underlines the paradoxical nature of the relationship between immigration and the governance of religious diversity: ‘While the immigrant integration policies of the Austrian state are very restrictive, its policies of religious accommodation are exceptionally inclusive’ (Çitak, Reference Çitak2013: 170). The Islamic Religious Community in Austria (Islamische Glaubensgemeinschaft in Österreich, IGGiÖ) was founded in 1979.Footnote 4 Since the 1980s, Turkey has reorganized its policies regarding the communities abroad by launching a strategy of caring and using state agencies like the Diyanet. The Austrian Turkish Islamic Union (ATIB) was established in 1990 and is the Austria's largest Muslim organization. In 2020, it covers a total of 63 local associations distributed all over the country, of which six are in Vienna. To adequately evaluate this long-standing engagement, the analysis covers the period between the 1980s and 2019. And thirdly, it is important to take note of the recent change in Austria's regulation of Islam. In 2015, the country enacted a controversial ‘Islam law’ that has had a major impact on the management of Islam and the country's relationship with the Muslim communities. The actFootnote 5 amends the 1912 Habsburg law, which was enacted to recognize Islam as an official religion within the empire after it had annexed Bosnia-Herzegovina. The reform recognizes Muslim holidays, the status of Islamic graveyards, and the right to have Islamic pastoral care in public institutions. However, it sparked tensions within the Muslim associations and the IGGiÖ concerning the prohibition of regular foreign funding for Austrian mosques, imams, and religious centers, as well as the requirement that religious officers speak German.Footnote 6 This attempt to forge an ‘Islam with an Austrian character’,Footnote 7 is in line with a model of regulating Islam that is anchored in the national framework, ‘detransnationalized’ and ‘reterritorialized [to create] a sense of national belonging.’ (Çitak Reference Çitak2018: 384). The 2015 Islam law affected the Diyanet's transnational practices and has been fiercely opposed by Turkey. Mehmet Görmez, the former president of the Diyanet, said that ‘no country has a right to engineer a religion’, and that the law was a result of the wave of Islamophobia sweeping across Europe and the rise of the far-right.Footnote 8 As shown by the case of the 2018 expulsion of imams from Turkey, reported at the beginning of this article, the change in the regulation of Islam directly affects the Diyanet officers' maneuvers in Austria and the discourse they convey.

To get a better grasp of religious officers' contribution to Turkey's art of governing its diaspora, this article relies on organizational ethnography – a methodology that emphasizes the mutual connections between ethnographic and discursive approaches in the study of the everyday of organizational life (Ybema et al., Reference Ybema, Yanow, Wels and Kamsteeg2009: 7). This choice is theoretically informed by the ‘interpretative turn’ in social science, which attributes a central role to language and practices in the construction of social reality: Discourse (text) and practices (behaviors) are defined as mutually constitutive of and tightly bounded to each other (Yanow, Reference Yanow1996; Yanow and Schwartz-Shea, Reference Yanow and Schwartz-Shea2006). Thus, the changing practices and micro-level processes that occur within the framework of a broader public discourse are underscored. Ethnographic observations of the sessions in the mosques provide a perspective from the inside of the everyday relations and practices that reproduce power on the ground (Schatz, Reference Schatz2013: 1–12). In this vein, on the empirical level, the article draws on field research that I conducted on two occasions: between October and December 2017 and between May and June 2019. I observed the empirically visible agency of religious officers employed at ATIB mosques in Vienna: the Ertuğrul Gazi Mosque located in the 20th district (Brigittenau), and the ATIB Central Mosque in the 10th district (Favoriten). In this context, my previous fieldwork in Turkey was crucial, as I could refer to a list of contacts and references that allowed me not only to gain the trust of and attend four Qur'an seminars organized by Diyanet personnel in Vienna, but also to meet the preachers in private houses. Gender segregation in mosques meant that I could observe activities organized in the mosques' women sections.Footnote 9 They were supported by semi-structured and informal interviews with Diyanet officials – mainly women preachers (six) and one woman Qur'an teacher, and two members of the female sections [kadın kolları].Footnote 10 Moreover, the work examines directives, circulars, reports published by the Diyanet International Relations Department [Dış İlişkiler Genel Müdürlüğü] in Ankara and books for the diaspora, such as ‘Ahlãkım’ (My Morality), the fourth volume in the Diyanet's ‘The Fundamental Principles of the Muslim Faith’ series. Published by the Diyanet in 2009, the book has been translated into various languages and distributed to the branches in Europe. All translations from the original Turkish are mine.

The contribution of pastoral power to diaspora studies

Governmentality, the processes and instruments by which population is rendered governable through the construction, machination, and normalization of a set of governmental apparatuses and knowledge (Foucault, Reference Foucault, Burchell, Gordon and Miller1978: 102), allows expanding the approach of diaspora-making as a political, state-lead project. The literature that examines the expansion of state-led diaspora engagement initiatives and diaspora governance institutions around the world emphasizes the sending states' tendency to include the population abroad and the extraterritorial reach of state power (Waldinger and Fitzgerald, Reference Waldinger and Fitzgerald2004; Varadarajan, Reference Varadarajan2010; Collyer and King, Reference Collyer and King2014; Délano and Gamlen, Reference Délano and Gamlen2014; Gamlen et al., Reference Gamlen, Cummings and Vaaler2019). A critical scholarship has recently questioned the state-centric approach to diaspora studies. As Délano and Mylonas (Reference Délano and Mylonas2019) affirm, these studies have focused on why nation-states engage their diaspora but have disregarded the context in which these policies are implemented, the sub-groups they are targeting and the agency of various groups designing and implementing them. To this end, the authors say it is necessary to ‘open the ‘black box’ of the state and study the various actors driving diaspora policies’ (Délano and Mylonas, Reference Délano and Mylonas2019: 476). Shifting from the motives behind such initiatives to the ways and the instruments through which the states attempt to reach, influence, or coerce population outside their territories, pastoral power contributes to revamp and diversify these debates. As a form of governmentality, pastoral power is: (1) exercised over a flock of people on the move rather than over a static territory; (2) a fundamentally beneficent power, with the duty of the pastor being (to the point of self-sacrifice) the salvation of the flock; (3) a power that is always good in itself, with the shepherd serving the flock and acting as an intermediary between the flock and pasture, food, and salvation; and (4) an individualizing power, as the pastor must care for every member of the flock (Foucault, Reference Foucault2009: 125–129). In its original definition, pastoral power originates with Christianity,Footnote 11 the only religion which has organized itself as a Church, and as such it postulates that certain individuals can by their religious quality, serve the others not as princes or magistrates […] but as pastors (Dreyfus and Rabinow, Reference Dreyfus and Rabinow1983: 214).

It initially manifests as a power of care, in its zeal, devotion, and endless application. The pastor is someone who keeps watch because his office is not primarily defined as an honor but rather as a burden and effort (Foucault, Reference Foucault2009: 127). However, as Martin and Waring (Reference Martin and Waring2018) affirm, few studies have investigated how the relations between the pastors and the communities are shaped or how the government's discourse is translated and diffused and the various actors within (and beyond) the state who play a role in exerting this control.

In the light of these considerations, Foucault's notion of pastoral power contributes to diaspora studies encouraging an approach ‘from within’ by shedding light on ‘the techniques the pastors employ to communicate, translate and adapt the governmental discourse to individual subjectivities’ (Martin and Waring Reference Martin and Waring2018: 1303). This contribution is threefold. First, it sheds light on the daily practices and discourses of the actors. Pastoral power has recently received attention from scholars who further develop the concept and view contemporary pastors as ‘experts’ and professionals in matters related to education, well-being, welfare, and health care (Biebricher, Reference Biebricher2011; Martin and Waring, Reference Martin and Waring2018; Tsinovoi and Adler-Nissen, Reference Tsinovoi and Adler-Nissen2018; Waring and Latif, Reference Waring and Latif2018). This approach makes it possible to investigate those practices and technologies of government (O'Malley et al., Reference O'Malley, Weir and Shearing1997) through which the power of discourse is spread and translated into subjectivities and actions.

Second, pastoral power contributes to diaspora studies by disentangling the relations between these practices and the sending states. It helps to emphasize the actions – and the interactions – through which extraterritorial power is exercised. While assessing the state's control mechanisms that go beyond the state's territorial limits, Michael Collyer and Russell King distinguish between the direct control of physical space, a symbolic control of transnational space, and a discursive control of imaginative space; they contend that where direct physical discipline is impossible or is socially sanctioned, symbolic and discursive practices of control are implemented (Collyer and King, Reference Collyer and King2014: 194–199). Similarly, Fitzgerald emphasizes how states resort to ‘creative forms’ and ‘symbolic instruments’ to manage their citizens abroad, preserve their national loyalty, and, if possible, extract resources from them (Reference Fitzgerald2008: 34–35). In a transnational context, as the contract between the nation-state and its citizens abroad is not based on legitimate coercive belongings, the state resort to pastoral power as ‘a power exerted over a multiplicity rather than on a territory’, a power that ‘guides towards an end and functions as an intermediary towards this end’ (Foucault, Reference Foucault2009: 129). Third, pastoral power contributes to the assessment of how interactions between the pastors and their flock shape the diaspora's perception of itself as a community. This aspect helps to grasp the sending states' mechanisms aimed at including or excluding segments of the diaspora, fostering the loyalty to the home country, and essentializing national and religious belongings (Hashas et al., Reference Hashas, de Ruiter and Vinding2018). According to Marlie Glasius, states' attempts to secure their diaspora's loyalty are particularly evident in authoritarian regimes. For stabilization purposes, the authoritarian state employs three different types of measures to include its citizens: ‘as subjects (to be controlled and repressed), as patriots (getting them to buy into legitimation strategies) or as clients (with potential for co-optation)’ (Glasius, Reference Glasius2018: 186).

As a lens through which to analyze the daily practices and discourse that Turkey uses to foster its connection to the diaspora, the pastoral power exerted by Diyanet officers expands the literature analyzing the plethora of institutionsFootnote 12 geared toward enhancing the Turkish state's authority beyond its territorial borders. These institutions are included in the country's push for ‘public diplomacy’ and form part of several soft-power strategies (Çevik, Reference Çevik2019; Benhaïm and Öktem, 2015).

Inside the Diyanet officers' pastoral activity

The activities conducted by Diyanet officers abroad have been fundamentally reshaped since the early 2000s, when the number of imams and preachers sent to Europe increased and their activities were professionalized. Women have also been included in the quota of preachers sent abroad, reflecting a concomitant process in Turkey where women are employed as professional preachers and religious experts at both the local and the national level (Tütüncü, Reference Tütüncü2010; Maritato, Reference Maritato2018). To assess the blossoming of the activities conducted by Diyanet personnel outside Turkey, it is important to relate them to the current redefinition of the Diyanet's General Directorate of International Relations. An example is the Department of ‘Religious Services Abroad with Social and Cultural Content’ (Yurtdışı Sosyal ve Kültürel İçerikli Din Hizmetleri), which was created to pigeonhole and coordinate all social and cultural activities that fall outside the mosque. The activities organized by the Diyanet Department for International Relations are, in this regard, extremely far-reaching. I observed how children learning the Qur'an, sermons for teenagers in the afternoon, Qur'an exegesis and religious seminars for women, and programs for families and the elderly all combine Islam with socio-cultural activities. The idea of Islam as a ‘social fact’, as it has been spread since 2003 when Ali Bardakoğlu became president of the Diyanet, relates to a catechism for Turkish society, which occurred via an increasing number of religious officers and activities (Bardakoğlu, Reference Bardakoğlu2009). The revitalization of this moral engagement suggests a redefinition of Turkish secularism in its assertive republican conception as state control over religious affairs (Kuru, Reference Kuru2007; Zengin, Reference Zengin and Turner2013).

In 2019, according to the Diyanet's official statistics, 1931 of its religious officers were serving abroad (Diyanet Işleri Başkanlığı, Strateji Geliştirme Başkanlığı 2020: 21). At the time of this research, 89 religious officers were working at the Diyanet Foundation in Austria (Diyanet Işleri Başkanlığı, Strateji Geliştirme Başkanlığı, 2018: 75–76). The contingent to be sent abroad comprises officers already employed by the Diyanet. The graduates from Faculties of Theology must have a minimum of 2 years of religious higher education, 5 years of experience as religious officers and scored at least 60 out of 100 points in the placement test for professionals (Mesleki Bilgiler Seviye Tespit Sınavı). Moreover, in 2006, the International Theology Programme was established to train young diaspora Turks in Islamic Studies at Turkish universities (Bruce, Reference Bruce2020), and in 2010, the first graduates were sent to serve as officers in Turkish diaspora communities. All religious officers spend a period abroad which can be short (2 years) or long (5 years) and can be repeated only twice, following 2 years of activity in Turkey. The tested competences in religious knowledge make them experts in the field of religion. The legitimacy of religious officers derives mostly from religious education, as the Austrian Diyanet Foundation's (ATIB) website makes clear:

‘Religious services are provided exclusively by expert theologians with additional pedagogical training, who take into account the needs and wishes of the communities. In their work, the religious officers (imams) attach great importance to using the main sources of Islam, the Qu'ran and the Sunna (the tradition of the Prophet), which are free of superstition and heresy.’Footnote 13

The professionalization of imams and preachers as ‘religious experts’ and the development of a wider range of activities are evocative of what Nielsen has recently defined as a ‘process of ecclesiastification’ in which the ‘imam as a priest’ (Nielsen, Reference Nielsen, Hashas, de Ruiter and Vinding2018: 14–5) is modeled on Christian pastoral theology (Vinding, Reference Vinding2018). Therefore, the flourishing of activities organized by Diyanet imams and preachers working as professional religious experts ties into this debate.

However, religious officers' distinction as experts theologians should be combined with their ability to reach the flock and be perceived as ‘one of them’. In Foucault's definition, pastoral power is a form of power that ‘cannot be exercised without knowing the inside of people's mind, without exploring their souls’ (Dreyfus and Rabinow, Reference Dreyfus and Rabinow1983: 214). As I could experience during my fieldwork, the organized activities expanded from preaching, ceremonies, courses on Islamic knowledge, sermons, religious guidance, conferences and seminars to social and cultural activities such as picnics, short trips, music and art classes, visits to hospitals and prisons, and a call center for questions related to religion. In this way, the preachers establish a close relationship with the community attending the sessions and their multifaceted activities are in line with pastors' engagement in promoting morally desirable models of behavior, instructing, caring for, and deriving legitimacy from the community they serve (Martin and Waring, Reference Martin and Waring2018: 1295).

The book ‘Ahlãkım’ (My Morality), the fourth volume in the Diyanet's ‘The Fundamental Principles of the Muslim Faith’ series. The book, published by the Diyanet in 2009, has been translated into various languages and distributed to communities abroad. It describes morality as a conditio sine qua non for a pleasing and blessed society.Footnote 14 Moreover, it contends that individuals must follow the moral norms and abide by a positive way of conduct, which includes the values of uprightness, generosity, chastity, ‘a principle at the heart of religiosity including patience vis-à-vis sexual temptations’, decency, ‘a sentiment of shame and embarrassment able to protect those who are pursuing amoral intentions’, and honesty, to attend to brotherhood (Diyanet Işleri Başkanlığı, 2009: 10).

While aimed at teaching, guiding, and informing about Islamic knowledge and moral behavior, the actions of imams and preachers are not a sporadic service that individuals may resort to at a particular moment of life. On the contrary, this religious guidance echoes one of the main features of the Christian pastorate:Footnote 15 ‘permanent, and one is directed with regard to everything and for the whole of one's life’ (Foucault, Reference Foucault2009: 181–182). Diyanet officers' sessions reflect one of the main features of pastoral power: an individualizing power directed at all and each in their paradoxical equivalence, and not at the higher unity formed by the whole (Foucault, Reference Foucault2009: 129). While attending to the communities' well-being, Diyanet officers' work is indeed different from giving spiritual guidance over the counter. It rather combines individualization techniques with totalization procedures.

This aspect was clear at women's meetings I attended. Diyanet preachers were listening to and answering women's personal concerns and providing ad hoc answers. Describing her daily work, Zehra, the preacher of Vienna Ertuğrul mosque affirms: ‘Here [in Austria] you have to do all the tasks: you are at the same time a preacher, a Qur'an teacher, a psychologist [italics mine].’Footnote 16 Religious counseling and moral support provided by the preacher are perceived as similar or alternative to consultations with psychologists. Hatice, the president of the Austrian Diyanet female section further elaborates saying:

‘Most of the women attending the sessions are elderly, often they are widows and spent all day at home alone. For them going to the mosque is a therapy, they socialize, share their problems, also many of them live in the vicinity of the mosque.’Footnote 17

Individual care presupposes proximity beyond the sessions scheduled at the mosques. In her study of the discourse of Diyanet women preachers in Turkey, Fatma Tütüncü talks about a ‘populist yearning to illuminate and empower ordinary Muslim women who have no access to genuine religious knowledge’ (Tütüncü, Reference Tütüncü2010: 611). According to the author, as far as women preachers are concerned, ‘populism is integral to preaching because without loving people, without going to people and without knowing people, one cannot be an effective preacher’ (Tütüncü, Reference Tütüncü2010: 605).

Diyanet officers' mission to go to the people and care for individuals is of particular relevance in the diasporic context. When visiting Turkish emigrants at home or in hospitals, the imams and the preachers gain access to private spaces in a way that is closed to almost any other state apparatus. Moreover, the condition of being Turkish officials, highly qualified in religious education, builds legitimacy and confers upon the individual a degree of distinction as an ‘expert’ and a full-fledged pastoral actor. In this regard, the strength of pastoral power as a governmental technique facilitating a connection between governmental discourse and the constitution of subjects lies in pastoral actors' ability to combine bottom-up practices of care and top-down normative discourses. The next section examines how micro-practices mirror state objectives and relate to the Turkish state's attempt to include diaspora communities by exerting pastoral power that combines caring with control.

Pastoral care and Turkey's extraterritorial practices

Although Diyanet imams and preachers have been instrumentally employed as a megaphone for the ideology of the ruling elite since the Diyanet was established (Öztürk, Reference Öztürk2016), the latter's international mission entered a new phase since the 1980s. At that time, the ‘Turkish-Islamic synthesis’ – the nationalist and religious conservative state ideology – was indeed diffused from Turkey to the communities abroad. State pedagogies (Şenay, Reference Şenay2012: 1619–1621) have been spread abroad with the intent to both hinder political opposition (Yurdakul and Yükleyen, Reference Yurdakul and Yükleyen2009) and sharpen a ‘strategy of maintenance’ (Amiraux, Reference Amiraux, Nielsen and Allievi2003) aimed to foster emigrants' loyalty to a set of values shaping their ethnic and national identity (Çitak, Reference Çitak2018).

Against this backdrop, in the past two decades, the Diyanet has emerged as a key diaspora institution (Allievi and Nielsen, Reference Allievi and Nielsen2003; ; Öktem, Reference Öktem2012; Okyay, Reference Okyay2015; Mencutek and Baser, Reference Mencutek and Baser2018; Öztürk and Sözeri, Reference Öztürk and Sözeri2018 ) operating in a ‘transnational social field through specialized institutions with the acceptance of receiving states’ (Bruce, Reference Bruce2020: 1168).

This art of governing is not only based on practices disguising power relations but also on the relationship between communication and objective capacities. On many occasions during my fieldwork, I could assess how the multifaceted activities conducted by Diyanet officers mirror the Turkish state's symbolic and creative instruments to reach diaspora.

Against this backdrop, the diaspora is perceived as merely a passive recipient of the sending state's discourses and practices. In Foucault's conceptualization, power is actions brought to bear on possible actions and is similar to the term ‘conduct’, which means to lead and refers to a way of behaving within a field of possibilities. The exercise of power implies the act of guiding the possibility of conduct and ensuring a particular outcome. Thus, government pertains not only to the management of the states but also the way in which individuals' or groups' conduct might be directed (Dreyfus and Rabinow, Reference Dreyfus and Rabinow1983: 220–221).

I could experience how the Turkish government's narrative abroad replicates its three main pillars – the family, Islam, and the homeland – and attempts to influence the diaspora's way of conduct. In his book ‘Nationalism and sexuality’ George Mosse notes how the protection of the family and national identity are extremely intertwined: on the one hand national ideals penetrated the family, on the other hand, the family was supposed to mirror and reproduce state values. In this representation, the woman was at the same time idealized as the guardian of morality, as well as public and private order, protecting the continuity and the immutability of the nation, and its morality (Mosse, Reference Mosse1988: 18)

This discourse, as we will see in the next section, also strongly mobilizes a feeling of national belonging expressed by a hyper-essentialist term such as ‘Turkishness’, a process that Ragazzi defines as ‘nationalization’ of the diaspora (Ragazzi Reference Ragazzi2009: 389–390).

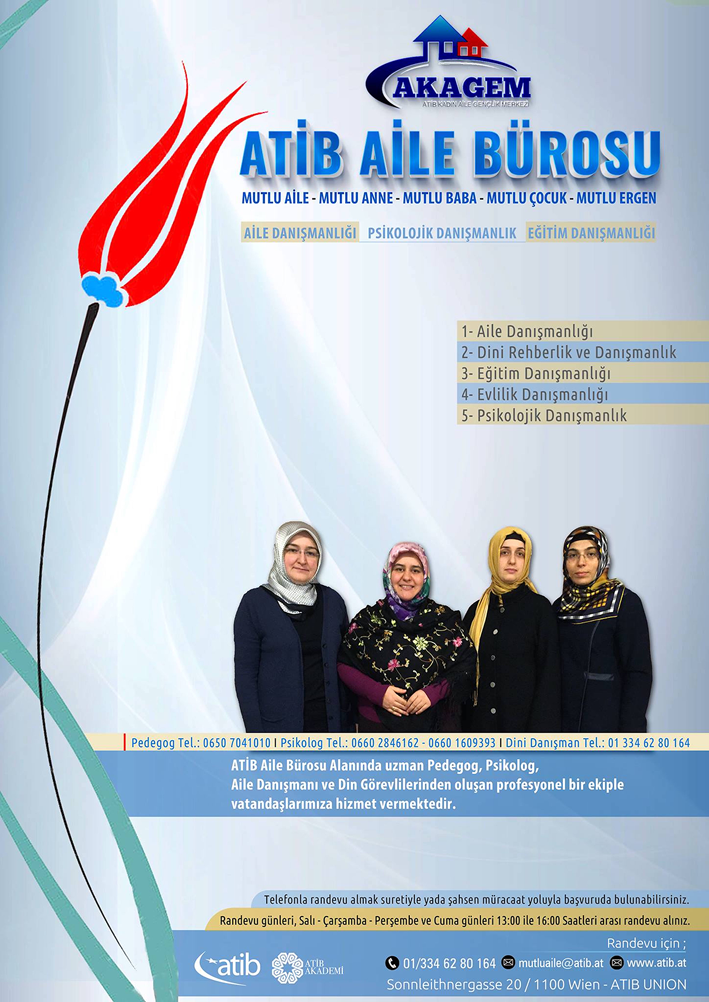

The traditional Turkish family is ideally composed of a man, a woman, and children, being three-generational (elderly, parents, and children live together) and based on notions of morality, honor, and respectability. As far as it concerns the family, the preachers I met in Vienna referred to the Austrian Happy Family Support and Counselling Project (Avusturya Mutlu Aile Destek ve Danismanlik Projesi) launched in 2013. As illustrated in the flyer (Figure 1), the project was made up of a several seminars and panels, counseling services, and cultural activities organized over 6 months in some of Austria's largest cities. Issues related to the family, parenthood, and childcare were presented by religious officers together with psychologists and pedagogues. The Family and Religious Consultation Bureaus were established to be similar to those in Turkey.Footnote 18 Equipped with a desk, a computer, chairs, and a couch where the preachers provide individuals with moral support and religious guidance, these offices are evocative of how institutions and practices are replicated in toto in the diaspora. Like these practices, the discourse on Western values threatening the traditional Turkish family also reflects one of the central tenets of the AKP agenda (Yazıcı, Reference Yazıcı2012; Kaya, Reference Kaya2015; Yilmaz, Reference Yilmaz2015; Kocamaner, Reference Kocamaner2019). The opening sentence of the project's 139-page final report is very clear in this regard:

‘The family structure of the Turkish communities living in Austria is affected on daily basis by external factors seeking to corrode it, and this substantially menaces the future of our community [emphasis is mine] […] The fact that the divorce rate in Europe is almost 57% is a tangible and serious example. That is the reason why we have undertaken this project.’

This aspect was clear to me when I met Hatice, the president of the women's sections (kadın kolları) of the Austrian Diyanet Foundation. While explaining why their activities are especially oriented toward families she affirmed:

‘In the families here, there are many problems – divorce, but also physical and psychological violence. That's why we provide support (aile danışmanlık), we organize seminars and visit families at home, as well as elderly people who are alone and those who are hospitalized.’Footnote 19

Figure 1. Poster of the Family Bureau, Austrian Diyanet foundation (ATIB).

In addition to strengthening the traditional Turkish family, Diyanet officers propagate this blend of religion and nationalism, Islam, and the Turkish homeland. A blossom of studies address the role of religion in foreign policy (Warner and Walker, Reference Warner and Walker2011), international relations (Haynes, Reference Haynes2001) as well as the religious actors' local response to international issues such as the refugee crisis and migration (Lyck-Bowen and Owen, Reference Lyck-Bowen and Owen2019; Itçaina, Reference Itçaina2018; Bassi, Reference Bassi2014; Caponio and Borkert, Reference Caponio and Borkert2010: 74–79). From the Scalabrinian Missionaries of Saint Charles founded in 1887 to maintain the Catholic faith and practice among Italian emigrants in the New World, to the role played by the Irish Catholic Church with respect to the Irish diaspora (Gray, Reference Gray2016), home states have employed religious officers to govern populations living outside their territory by exerting pastoral power. This consists of a system of obedience and subordination (Foucault, Reference Foucault2009: 235) that relies on meanings, symbols, rituals, and morals. Different from the Catholic Church, the Diyanet is a Turkish state agency and the activities of imams and preachers abroad directly contribute to Turkey's attempt to govern the diaspora through the obedience to both religious principles (afterlife salvation) and the Turkish nation-state.

Besides Diyanet officers' practices, publications also play a crucial role in this respect. In its work on the activities conducted by the Catholic priests sent to serve Mexican immigrants in the USA, David Fitzgerald underlines that ‘the tools of contemporary pastoral power directed at emigrants include publications, clerical training and surveys’ (Fitzgerald, Reference Fitzgerald2008: 88). Booklets, books as well as websites, TV programs, and social networks are tools that allow assessing how discourse and practices converge to achieve the objective of controlling the conducts. As Dreyfus and Rabinow affirm, govern is the result of power relations, relationships of communication and objective capacities, three types of relationships ‘which always overlap one another, support one another reciprocally, and use each other mutually as means to an end’ (Reference Dreyfus and Rabinow1983: 217–218).

The ‘My morality’ volume, cited above, is in this sense evocative. After presenting the notion of morality in Islam, it tackles the ‘Duties and the Responsibility towards God, the Prophet, ourselves, our family, our neighbors, our entourage and the state as homeland (vatan).’ The section concerning the state reads as follows:

‘The state is the name of an institutionalized political sovereignty of a people living within a country's borders, and it is the most important social institution governing the people. […] The state has a duty to ensure people a stable existence in safety, unity, and peace. Together with social stability, the state also has a duty to protect the religious belief of the population. People have to follow those who govern the state towards this end. […] The state represents the force, authority and continuity. […] Our Prophet (s.a.s) states it is mandatory to obey the state officials who govern the people. […] Protecting the state is a duty and a moral responsibility. The state's social, economic, and military power provides force and respect for the individuals both at home and abroad. (emphasis is mine)’ (Diyanet Işleri Başkanlığı, 2009: 88–89)

As this excerpt shows, the state's pedagogies are propagated abroad through the Diyanet to instill both a sense of responsibility and blind obedience to the state and its officials. Diyanet officers thus exert a pastoral power which translates the government's discourse to the diaspora and contributes to Turkey's attempt to forge diaspora as governable subjects.

This obedience is also expressed as love for the nation. The chapter addressing ‘Love in the Islamic Morality’ includes a section on ‘Love for the Motherland and the Flag’. A picture of the map of Turkey (Figure 2) is colored by the Turkish flag, and a paragraph states:

‘The country and the flag are symbols of freedom. The country is not just land. It is the place where our people live, where it acts with its culture and where it develops. Our people come together under common values, a common flag, and a common land. To do whatever is necessary for the glory of our country and our people is a sign that we love it’ (Diyanet Işleri Başkanlığı, 2009: 112).

The reference to ‘common values, common flag, and common land’ and the persistence of sections like ‘The love for the motherland’ in a book conceived to spread religious knowledge is consistent with the Diyanet's mission to propagate the state ideology. The Article 136 of the 1982 Constitution tasks indeed the Diyanet with protecting the ‘national integrity and solidarity’.

Figure 2. Picture of Turkey's Flag. Ahlãkım [My morality], p. 112.

The political role inherent in the Diyanet means that the institution consolidates national unity while carrying out its activities abroad:

‘Our flag's color is the blood of our martyrs. Therefore, we must demonstrate our respect for the flag. […] The motherland and the flag occupy an important place in one's existence. Sometimes people might be forced to protect or avoid attacks against their country and their flag. To protect and defend the nation is one of the signs of love to the latter’ (Diyanet Işleri Başkanlığı, 2009: 113).

One of the elements through which the link between the nationalist and the religious discourse is strengthened is the notion of martyrs. Martyrdom as a way of reconciling religious ideology with mundane politics recurs in Islamist movements and parties. The literature has mainly focused on Hezbollah in Lebanon (Hamzeh, Reference Hamzeh2004; el-Husseini, Reference el-Husseini2008) and in Iran by addressing how the memorialization of martyrs re-animates and sacralizes the national landscape (Wellman, Reference Wellman2015). In the case of Turkey, the Diyanet associates the figure of the martyr with the soldier, thereby sealing the sanctity of the military nation (Altınay, Reference Altınay2004; Arjomand, Reference Arjomand2017). The book ‘My Morality’ has a section devoted to ‘The Martyr and the Veteran’ which makes this point very clear: After citing a passage from the Qur'an (Al-I Imran, 3/169-170), it defines the martyr and the veterans as follows: ‘The highest awards for those protecting the nation […]. The highest status a person may reach. […] [A]ll the sins of the martyr are forgiven’ (Diyanet Işleri Başkanlığı 2009: 114). In the same section, an entire page (Figure 3) is dedicated to the Turkish War of Independence and the Dardanelles Campaign, which are cited as examples of martyrs' sacrifices in defense of their country. The section concludes with a picture of the Dardanelles Campaign and a quote from Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk) congratulating the ‘Turkish people’ for their heroic behavior.

Figure 3. Picture of Dardanelles Campaign. Ahlãkım [My morality], p. 114.

In the Diyanet's official textbook, Turkey not only represents the country of origin whose cultural and religious links should be cemented. It is also an ideal homeland to be proud of and that one should be ready to protect. This aspect resonates with one of the main characteristics of the diaspora, namely the myth of the ideal homeland and the aspiration to return (Cohen, Reference Cohen1996). However, the commemorations of the Battle of Gallipoli, cited at the top of this article, reflect how religion and nationalism intertwine in the construction of the migrant self in Turkish mosques in Europe but have also been Islamized as an Ottoman-Islamic defensive campaign against the infidels.Footnote 20 In this vein, ‘Turkishness’ is not a condition to be protected in a passive-defensive way but entails a pro-active sense of belonging. The next section analyzes how the discourse that Diyanet officers convey to the diaspora community affects the process of ‘nationalization’ in essentialist terms that, according to Ragazzi, constitutes one of the levels in which the diaspora politically exists (Reference Ragazzi2009: 389–390).

Patriots vs. traitors: Turkish state shaping the diaspora's boundaries of belonging

The interaction between Diyanet officers and the flock contributes to shaping people's perception of themselves as part of a community and to remapping the diaspora's boundaries of belonging. The Diyanet officers' agency sheds light on the multiple tools Turkey uses as it seeks to build loyal and enduring relations with the diaspora. In an attempt to reincorporate ‘its’ emigrants, the Diyanet's activities in Europe speak to the relationship between nation and state and, in particular, the twofold understanding of the nation that Brubaker (Reference Brubaker and Hall1998) distinguishes as state-framed and counter-state. In the first sense, the national and the state boundaries overlap, and the nation is defined as a political unit of the citizens of the state. In the second, the nation as a community claimed on the basis of a shared language, history, and culture might stand in opposition to the territorial state (Brubaker, Reference Brubaker and Hall1998). When governments frame the nation as one that extends beyond the state's borders, diasporic nationalism as ethnic nationalism (Ragazzi Reference Ragazzi2009) reproduce ethnic or religious minority questions.

Scholars who have analyzed Turkey's long-standing mechanisms to monitor and control diaspora groups it perceives as dissidents emphasize how they have evolved, including in terms of authoritarian practices and discourses aimed at excluding different segments of the diaspora (Yükleyen, Reference Yükleyen2011; Ünver, Reference Ünver2013; Aksel, Reference Aksel2014; Öktem, Reference Öktem2014; Adamson, Reference Adamson2019; Mencutek and Baser, Reference Mencutek and Baser2018; Watmough and Öztürk, Reference Watmough and Öztürk2018; Baser and Öztürk, Reference Baser and Öztürk2020).

This process also contributes to essentializing belonging and perception of oneself as part of a community. Framing home states' extraterritorial authoritarian practices, Glasius emphasizes how the notion of ‘national loyalty’ in an authoritarian context is dichotomized as either ‘inclusion as patriots’ or ‘exclusion as traitors’ as a result of the good/bad behavior of the population abroad (Glasius, Reference Glasius2018: 188). Home countries deploy a binary we/them discourse of inclusion or exclusion – the very same opposition that overlaps with a polarization aimed at opposing two perceived homogenous and antithetic models of the East and West, religious and secular, patriots and traitors, which have their roots in the rhetoric of the Turkish far right since the 1950s (Aytürk, Reference Aytürk2014; Bora, Reference Bora2018). This framework is appropriate to analyze Turkey's current attempts to strengthen the diaspora loyalty as it emphasizes two relevant features: First, it occurs through a binary discourse we–them which polarizes and opposes two perceived homogenous and antithetic models of the East and West, Muslim Turks and secular Europeans. Second, this dichotomy reflects a polarization that is also propagated in the home country where the criminalization of the opposition targets political parties, politicians, and activists (Kaya, Reference Kaya2018).

As we have seen in the previous section, while teaching and assuring the moral behavior within the community, Diyanet imams and preachers are also tasked with strengthening the link between Turkey and the Turkish community abroad. This occurs through the spreading of a discourse focused on religious and national Turkish values and through the reiteration of a home state's paternalistic mission to include and embrace diaspora communities. The continuity between Turkey and Turkish communities abroad is strengthened by a highly stereotyped discourse that permeates Diyanet officers' activities. In many conversations, my interlocutors referred to ‘European women’ and ‘European families’ as lacking morality, being far from religion and unable to take care of children and elderly people. Attending the sessions in mosques and behaving piously in daily life is indeed designed as an antidote to any possible attempts to assimilate to the ‘European model’. This process allows no place for hybridity or multiple belongings. On the contrary, when I inquired about the differences between the women she worked with in Turkey and the ones in Austria, Emine, the preacher working in Diyanet's Brigittenau mosque in Vienna, emphasized a strong continuity: ‘Women attending the sessions here are the same as the ones you can find in mosques in Turkey. This is our community [toplumuz]; they are not different.’Footnote 21

However, the Turkish state's attempt to maintain a link with communities abroad and shape a homogenized Sunni Turkish diaspora should not be read exclusively as a one-way process in which the Diyanet officers are merely instruments or megaphones (Öztürk, Reference Öztürk2016) through which the state's narrative is spread abroad. Diyanet officers contribute by using their own agency not only to spread this narrative, but also to build it. While conducting activities within the diaspora, state officials have or may require access to information that can be used in governing. This occurs mostly through surveys and reports that the Diyanet foundations abroad are tasked with developing. The 2019 report of the Diyanet's activities clearly states that the Diyanet examines, controls, and archives the reports on the activities conducted by the offices abroad and their annual action plans (Diyanet Işleri Başkanlığı, Strateji Geliştirme Başkanlığı 2020: 34–35).

While reports and surveys allow Ankara to be informed about activities conducted abroad, religious officers also provide field information about political and religious activities conducted by Turkish communities outside Turkey. Moreover, the religious attachés employed at embassies and consulates supervise imams' and preachers' activities – a process that has recently raised concerns as it pertains to the spaces of maneuvering political opposition. In the aftermath of the coup attempt in 2016, imams were accused of being on the frontlines by controlling and reporting about members affiliated with the Fethullah Gülen community.Footnote 22 As a result, imams and preachers sent to the diaspora are deeply entrenched in the politics of the Turkish state actively diffuse AKP narrative.

Moreover, the Turkishness and the love for the motherland the Diyanet officers are exporting abroad might confront a Kurdish composition of the communities. The ethnic difference, as in the case of mainly Kurdish communities, is overcome when conservative and moral conduct is displayed. Describing her monthly activities in Graz, Austria's second-largest city, Emine, one of the preachers in Vienna, refers to the fact that the community is Kurdish and says: ‘They are Kurds, but at least they speak Turkish so that we can communicate! But they are good [iyi] Kurds.’Footnote 23 The moral judgment of ‘good’ Kurds here is crucial as it reflects the government's narrative of good (pro-government and religious conservative) Kurds vs. so-called bad (those opposing the government and/or the Turkish state) Kurds.

In this attempt to propagate a model of the emigrant who is loyal to the motherland, and the expression of a religious discourse blended with Turkish nationalism (White, Reference White2013), the Diyanet seems to be perpetuating its role as it was under the paternalistic and coercive Kemalist state's art of ruling both in Turkey (Aymes et al., Reference Aymes, Gourisse and Massicard2014) and abroad (Şenay, Reference Şenay2012). The similarities and differences in the ways Diyanet officers are engaged in spreading the ruling ideology abroad, therefore, needs to be scrutinized further, along with the implications of the reproduction of societal conflicts from Turkey to abroad.

Concluding remarks

This article investigates how state-led diaspora institutions function at micro-levels and what they reveal about the instruments that states deploy to embrace and govern ‘their’ diaspora as a ‘domestic abroad’. In particular, it relies on the notion of pastoral power, a power that is exercised over individuals rather than a territory and involves pastoral actors engaged in caring and directing the multiplicity.

The work is empirically grounded in the activities of religious officers sent by the Turkish Presidency of Religious Affairs (Diyanet) to serve in Turkish Muslim communities in Europe. Since the 1980s, the Diyanet has promulgated the ‘Turkish-Islamic synthesis’– the nationalist and religious conservative state ideology – also within diaspora communities. However, in the past two decades, this international mission expanded to foster the loyalty of the communities abroad. This attempt to manage the cultural and socio-political effects of emigration occurred through similar expressions of a pastoral power (Fitzgerald, Reference Fitzgerald2008: 35), which included spreading moral imperatives and governmental discourse, guiding individuals to internalize moral conduct, normalizing self-governing practices relating to individual behavior with the shared moral expectations of the community.

In this regard, one of the article's main points is that Diyanet officers sent to Europe embody the role of contemporary pastors as religious experts. Aiming to care for and govern the communities they serve, the pastors provide individualized spiritual guidance and moral support. Therefore, their agency informs how the link between the pastors and the flock is shaped, that is, how governmental discourse is communicated and translated to the individual subjectivities. The article emphasizes the relational practices that enable Diyanet officers to address individuals while targeting the community as a whole. The legitimacy of their role derives from both their tested competences in religious education and their status as civil servants under the supervision of Turkey's embassies and consulates. In this sense, the Diyanet's officers sent abroad perform as religious experts teaching diaspora communities about religious knowledge and moral principles. However, fieldwork observation of the activities of the Diyanet's preachers sheds light on religious counseling combining basic principles of morality and religious knowledge with national symbols, obedience to the authority, love for the homeland, and protection of the family as an immutable entity.

Thus, a third main point concerns how religion and nationalism intertwine in the construction of a pro-active sense of belonging and of a mobilized and politicized immigrant self in Turkish mosques in Austria. The article contends that Diyanet mosques in Austria are a vantage point from which to analyze not only how Sunni Islam and nationalism are diffused, but also how a Turkish Muslim diaspora is nurtured and defined in essentialist terms. In this regard, the commemoration of the Battle of Gallipoli reveals how the relations between authority, territory, and population are rationalized, organized, and legitimized at a transnational and an international level (Ragazzi Reference Ragazzi2009: 383). Against this backdrop, Diyanet officers translate and propagate the government's nationalist and religious conservative ideology through their sermons and daily activities. In line with authoritarian extraterritorial practices aimed at dichotomizing the conduct of a population abroad by dividing it into patriots vs. traitors (Glasius, Reference Glasius2018), this discourse seems not able to include hybridity. In the aftermath of the 2016 attempted coup, any subversive or resistant practice has been stigmatized and marginalized. However, what seems a coherent and unambivalent picture should be carefully analyzed: While strengthening the loyalty to the motherland and the belonging to a set of religious and cultural values, Diyanet officers address only a segment of the diaspora – the one loyal to the government and, therefore, more prone to being receptive to its discourse. In an attempt to turn the diaspora into docile subjects who defer to the government, there is a risk of translating and exacerbating tensions outside the state borders and polarizing the ‘good’ and the ‘bad’ emigrants. In this respect, the paper offers fertile ground for future research examining the political effects of state governmentalities beyond the national border as well as how oppositions elaborate counter-narratives and practices within the diaspora.

Funding

The research has been partially funded by the Austrian Agency for International Cooperation in Education and Research (OeAD)'s ‘Ernst Mach’ scholarship.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Kerem Öktem, Bilge Yabanci, Gül Üret, László Szerencsés, Anna Zadrożna, Franca Roncarolo, Luca Ozzano, Tiziana Caponio, and Roberta Ricucci with whom I discussed different stages of this article. I express my gratitude to Rosita Di Peri and the external reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions.