Introduction

Media play a pivotal role in shaping political dynamics. Especially in times of crises, they act as primary conduit through which citizens receive information regarding governmental policies and political actions, thereby influencing public opinion and political outcomes (Iyengar and Kinder, Reference Iyengar and Kinder1987; Zaller and Chui, Reference Zaller and Chui1996; Soroka, Reference Soroka2003). However, fair media coverage of events may be challenged by political leaders trying to diminish social problems in the attempt to avoid the electoral costs for their mismanagement (De Vreese et al., Reference De Vreese, Esser, Aalberg, Reinemann and Stanyer2018). This paper aims to shed new light on the nuanced ways media can be manipulated to control political narratives, using original television (TV) transcript data and focusing on the case of Italy during the 2011 financial crisis.

Our goal is to reevaluate the full chain of political communication effects, unveiling the mechanisms of political control exerted through media, and elucidating the consequential downstream impact of such mediated political influence on public opinion and voting behaviors. To this end, we use the case of a salient economic crisis to argue that media's portrayal of political events and economic policies, or the avoidance of those events and policy reactions, is not merely the reflection of objective realities but also the outcome of a strategic arena where political influences move editorial decisions.

Furthermore, the case of Italy can offer unique and interesting opportunities for observing the mechanisms of political influence on media and public opinion. On the one hand, it is a least-likely case for observing a political removal of news regarding the crisis, given that it suffered dramatically throughout the crisis due to its treasury bonds' interest rate spikes. On the other, Italy's media system, characterized by a high political parallelism (with the private Mediaset networks being owned by Mr. Berlusconi's holding) and government-appointed newscast directors for the public broadcasting company (RAI), offer strong political incentives for controlling public media editorial decisions (Grasso, Reference Grasso2004; DellaVigna et al., Reference DellaVigna, Durante, Knight and La Ferrara2016).

In particular, during the time when Berlusconi was Prime Minister, he could directly control Mediaset editorial decisions as their owner, and the Minister of Economic Affairs of his cabinet appointed the directors of the networks. Such appointments followed a criticized informal practice called “lottizzazione,” whereby Italian parties follow a questionable notion of external pluralism by assigning the first RAI channel (RAI1) to the largest governing party, the second channel to a junior party in the governing coalition, and the third channel to the opposition. While Italian political parties do not directly manage and control Italian public TV, this informal practice leads to a political influence over the appointment of directors, editorial choices, and programming decisions.

The issue of political influence and control over media is debated in most Western democracies. Although Italy stands out for its visible and structured system of political parallelism, scholars and practitioners noted growing political alignment across US TV networks (e.g. Fox News and MSNBC). Similarly, ABC in Australia attracts critics for its alleged left-wing bias, and the BBC in the United Kingdom has faced criticisms of exhibiting a pro-Europe stance. These instances underscore broader discussions concerning the necessary safeguards required to uphold the independence of public broadcasters.

Nevertheless, identifying the alleged chain of political influence and control over media and public opinion is inherently challenging due to various complicating factors, such as the self-selection of voters in news exposure. This issue introduces a methodological trade-off: observational studies grapple with selection bias due to the non-random consumption of news, while experimental studies often employ manipulations that may not fully reflect the dynamism of real-world news and political context, thereby limiting their external validity. To mitigate these limitations, we examine Italy during the 2011 financial crisis, utilizing the abrupt fall of Mr. Berlusconi's government as a plausible source of exogenous variation in political influence over media news coverage, and subsequent public political attitudes. This quasi-experimental approach facilitates a two-stage empirical strategy.

First, we investigate political influence on Italian TV networks using a difference-in-differences design, comparing variation in news coverage on RAI and Mediaset channels before and after the termination of Berlusconi's government. Specifically, we estimate news “content scores,” a composite scaling measure reflecting the position of a specific news edition within the latent space of all editions, enabling a nuanced comparison of shifts in media coverage. We primarily focus on public RAI channels, hypothesizing potential susceptibility to political influence, contrasting them with Berlusconi's Mediaset channels, which we assume remain unaffected by the political transition.

Second, we explore the downstream effects of this political shift in media control on public opinion and voting behaviors. We integrate the computed news content scores with data from the Italian National Election Study (ITANES), a representative panel dataset that includes information on respondents' preferred news channels. Given that, in the Italian context, individual self-selection predominantly manifests through channel selection rather than selective exposure within a preferred channel, we identify the causal impact of media coverage on individual political preferences and voting intentions by concentrating on longitudinal variations (within-channel and individual) prompted by preceding changes in the estimated news scores.

Central to our research design is an extensive, original corpus of televised news transcripts, encompassing over than 20,000 h of news stories. This corpus is comprehensive and detailed, incorporating broadcasts from both RAI and Mediaset between June 2011 and April 2012. Our analytical strategy employs unsupervised text scaling – a technique traditionally used to discern ideological positions from textual data, such as political manifestos – to detect and quantify shifts in the content of news media.

Previous applications of text scaling to news media have included newspaper editorials (Kaneko et al., Reference Kaneko, Asano and Miwa2021) and social media posts (Wihbey et al., Reference Wihbey, Joseph and Lazer2019). This study innovates by extending the methodology to televised news. By doing so, it uncovers and validates a latent dimension of news contents that ranges from “hard” news, covering socially relevant political and economic news, to “soft” news, such as personally relevant current affairs, lifestyle, gossip, and sports. This approach marks a departure from conventional measures of media bias that often rely on the proximity of media language to that of political actors (Gentzkow and Shapiro, Reference Gentzkow and Shapiro2010). Instead, our content-based measure independently charts the media landscape, distinguishing the predominant themes of news coverage. The result is a refined, continuous measure of news content, offering fine-grained scores at the level of individual news broadcasts, and allowing to potentially unveil new mechanisms of political control on media, as well as media influence on public opinion.

We find that during Berlusconi's tenure, public TV significantly under-reported political and economic news, replacing it with soft news content. Our estimates indicate an average reduction in the coverage of hard political events of approximately 107 seconds daily. Our analyses indicate a strategic reduction in the coverage of hard news, rather than by a change in the framing of those news stories. Regarding downstream electoral implications, we find that the reduction in hard news coverage significantly increased the propensity to vote for Berlusconi's party, the ratings of Berlusconi as a political leader, and the overall support for Berlusconi's government.

Our study shows the significant political consequences of news substitution as a form of political control, aligning with recent findings that underscore the influential role of soft news sources, such as British tabloids, in shaping public opinion (Foos and Bischof, Reference Foos and Bischof2022). Our finding that the strategic replacement of hard political and economic news with soft news has significant electoral implications aligns with previous evidence that exposure to Mediaset entertainment content caused a higher propensity to vote for Berlusconi's party in 1994 (Durante et al., Reference Durante, Pinotti and Tesei2019).

Our research contributes to several strands of literature. First, it empirically substantiates theoretical assertions regarding the pivotal role of the volume of political and economic news coverage in influencing public opinion and voting behaviors (Strömberg, Reference Strömberg, Anderson, Waldfogel and Strömberg2015b). Second, our study illustrates the efficacy of unsupervised text scaling as a robust measure of news content along the hard–soft dimension, complementing existing methodologies that assess the ideological bias of news (Gentzkow and Shapiro, Reference Gentzkow and Shapiro2010). Third, our findings enrich the discourse on the impact of entertainment-oriented soft news on public opinion (Zaller, Reference Zaller2003; Baum and Jamison, Reference Baum and Jamison2006; Kernell et al., Reference Kernell, Lamberson and Zaller2018). While existing literature posits that soft news can foster incidental political learning among the less-engaged citizens, our research introduces a nuanced perspective, suggesting that soft news can also be strategically utilized to divert attention away from pressing political issues.

Political control, media influence, and voter persuasion

Democracies are anchored to the triadic relationship between political actors, media, and citizens. Historically, scholarly discourse on the interplay between media and political actors has predominantly focused on the mechanisms of political control over media within emerging democracies, transitional societies, and authoritarian regimes. In these contexts, the exploration has been centered around understanding the extents and forms of governmental influence and censorship. Established democracies, conversely, have been primarily investigated through the lens of media acting as a check on political actors, embodying their role as the “fourth estate.” However, a nuanced shift in scholarly debates has emerged, unveiling surprising instances of economic and political influence permeating the media landscapes of even those societies where the press is ostensibly independent and free from overt censorship (Besley and Prat, Reference Besley and Prat2006; Schiffrin, Reference Schiffrin2018).

The rise of populist movements, processes of democratic backsliding, and multiple global crises have underscored the vulnerabilities of media independence, even in robust democratic media systems (Holtz-Bacha, Reference Holtz-Bacha2021; Rees, Reference Rees2023). Research has unveiled direct mechanisms of censorship, both in democratic and non-democratic systems (Corduneanu-Huci and Hamilton, Reference Corduneanu-Huci and Hamilton2022). However, more indirect forms of political influence can arise in the presence of networks of connections between political actors and media ownership, which facilitate the alignment of editorial narratives with referents' political objectives (Dragomir, Reference Dragomir2018; Gerli et al., Reference Gerli, Mazzoni and Mincigrucci2018). Such external influences tend to erode public service information, diminishing its watchdog role (Marques, Reference Marques2023). However, media also operate as autonomous entities driven by distinctive incentives and motivations. Accordingly, private media outlets may bias their news coverage to cater audience preferences, seeking reputational gains (Gentzkow and Shapiro, Reference Gentzkow and Shapiro2006). Media content also shapes, and it is shaped by, broader societal and political discourses, reflecting and influencing contemporary public and political conversations (Barberá et al., Reference Barberá, Casas, Nagler, Egan, Bonneau, Jost and Tucker2019; Gilardi et al., Reference Gilardi, Gessler, Kubli and Müller2022). Given these multifaceted interactions, distinguishing between politically motivated media control and independent editorial decisions presents significant empirical challenges.

The relationship between media and public opinion is central to political dynamics. Free and independent media, acting as a watchdog over governments, are functional to an informed and responsive citizenry. Research has established various effects of media on public opinion. Primarily, media can set the public agenda, as the quantity of news coverage dedicated to a political issue was found to shape its perceived salience in the public (McComb and Shaw, Reference McComb and Shaw1972; Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Stewart, Tingley, Lucas, Leder-Luis, Gadarian, Albertson and Rand2014). Additionally, media shape the frames of reference that guide public interpretation of political events (Scheufele, Reference Scheufele1999; Chong and Druckman, Reference Chong and Druckman2007). More generally, media have historically shaped the mechanisms of electoral decisions (Garzia et al., Reference Garzia, da Silva Ferreira and De Angelis2022), and voters form their perceptual images of political parties (De Angelis, Reference De Angelis, Suhay, Grofman and Trechsel2020) largely based on mediated information (Bellucci and De Angelis, Reference Bellucci and De Angelis2013; Strömberg, Reference Strömberg2015a; Garzia et al., Reference Garzia, da Silva Ferreira and De Angelis2020).

Economic crises offer a unique lens for examining the mechanisms of political influence on media, and, subsequently, media influence on public opinion: conditions of uncertainty and heightened public anxiety often become arenas of intense political maneuvering and media scrutiny. Political actors may employ various tactics to skew media coverage in their favor, crafting narratives that serve their interests. However, the efficacy of such strategies is not guaranteed due to several factors. First, the conspicuous nature of crises makes it challenging to deflect responsibility convincingly. Second, as Chong and Druckman (Reference Chong and Druckman2007) illustrate, counter-framing strategies might yield unintended consequences, primarily influencing sub-groups with lower political involvement. Lastly, the sheer volume of issue coverage can also directly affect public opinion responses (Shah et al., Reference Shah, Watts, Domke, Fan and Fibison1999). Media, in turn, play a pivotal role in public perceptions and attitudes amid economic downturns, guiding the reading and interpretation of events, attributing responsibilities, and framing the discourse around policy responses (Boomgaarden et al., Reference Boomgaarden, Van Spanje, Vliegenthart and De Vreese2011; Damstra and Boukes, Reference Damstra and Boukes2021).

In this paper, we advance the view that political influence on media and, consequently, media influence on public opinion can be achieved even in conditions of heightened scrutiny, such as in established democracies with media independence requirements and during economic crises. Political actors can subtly wield influence inducing media to selectively remove and replace politically sensitive news stories. This indirect influence aims to diminish the public's perception of an issue's significance, thereby limiting its impact in terms of electoral accountability.

Thus, besides established mechanisms of media bias, whereby media support certain frames and narratives to account for political events, we argue that political influence may be directed at strategically replacing politically relevant news with stories distracting public attention. The efficacy of this strategy is contingent upon various factors, such as the severity of the displaced issue and its social repercussions. The replacement stories must be sufficiently attractive to effectively engage media audiences. Scholars have long argued that the expansion of entertainment, facilitated by cable news and the Internet, has significantly impacted public's political knowledge and engagement (Zaller, Reference Zaller2003; Baum and Jamison, Reference Baum and Jamison2006; Prior, Reference Prior2011). While some research, such as Prior (Reference Prior2003), underscores a public inclination for political and economic news programs, other studies (Boczkowski and Mitchelstein, Reference Boczkowski and Mitchelstein2013) reveal a global trend where stories centered around celebrities and entertainment captivate substantial audience attention.

Such findings suggest that displacing political and economic news with soft information may be effective in reducing the political costs of a crisis. Arguably, media outlets under political influence will balance market and political considerations. While market dynamics require comprehensive coverage of crisis-related issues to meet viewer's demand, political influence can induce the recalibration of news content, even at the risk of audience reduction, to alleviate political costs. Indeed, evidence suggests that the majority of media users favors entertainment contents, and the share of “surveillance” citizens interested in regular use of news media is a declining minority (Hopmann et al., Reference Hopmann, Wonneberger, Shehata and Höijer2016; Gil de Zúñiga and Diehl, Reference Gil de Zúñiga and Diehl2019). Consequently, the strategic removal of political news can offer a subtle, yet effective, tactic for the minimization of the political fallout from adverse events preventing significant reductions in news consumption patterns.

Data and empirical strategy

We aim to identify two key relationships: the political influence stemming from government control of public media on the content of RAI newscasts, and the media effects on public opinion and voting behaviors. To this end, the research design unfolds in three parts. First, we rely on Teche RAI data, consisting of high-quality transcriptions of televised news on the main Italian networks, for estimating and validating news content scores through text scaling. Second, we apply difference-in-differences design to test whether the fall of Berlusconi's government would determine a variation in the estimated news content scores for RAI newscasts, using Mediaset as control. Third, we integrate the estimated news content scores with representative panel data from the ITANES to investigate whether changes in news content were consequential in shaping subsequent political attitudes and voting propensities.

The Italian context and events' timeline

TV news in Italy

The Italian TV market is characterized by a duopoly of two major groups and an additional independent channel, all of which operate nationwide on a free-to-view basis. RAI, the state-owned broadcaster, offers three primary channels, each featuring its own news program (in Italian, telegiornale, abbreviated as “Tg”): RAI1 (Tg1), RAI2 (Tg2), and RAI3 (Tg3). Mediaset, a private media conglomerate, is under the ownership of Silvio Berlusconi, Prime Minister and leader of the former center-right coalition Popolo della Libertà (People's Freedom Party). Mirroring RAI, Mediaset broadcasts news on three channels: Rete4 (Tg4), Canale5 (Tg5), and Italia1 (Studio Aperto). For analytical clarity, we refer to these networks as PUBLIC1–3 and BERLUSCONI1–3, respectively.

During the time frame of our analysis, RAI and Mediaset commanded between 85 and 90% of the TV market (Durante and Knight, Reference Durante and Knight2012). The Italian TV sector is further diversified by several local channels and a smaller national network, La7, owned by Telecom Italia Media until 2013 holding about 3% of the domestic market. The level of market concentration is significant for our study given that TV represents the predominant source of information in Italy.Footnote 1

RAI's governance is ostensibly under parliamentary control, but in practice, it is influenced by a special parliamentary commission predominantly composed of members from the governing coalition. This arrangement has historically led to lottizzazione (apportionment), a practice of allocating directorial positions of public network newscasts based on political criteria. Importantly for our study, the director of RAI1 (public) newscast – which boasts the highest viewership – was swiftly changed (on December 12th) following Berlusconi's departure from power (on November 12th), while the directorial positions of the other two public channels remained unchanged (see Table 1 for comprehensive details).

Table 1. Public TV newscast directors and timeline

Note: The table reports for every public channel the date of installment and end of the news directors, and their self-declared political affiliation.

Political timeline

We focus on the period between July 2011 and April 2012, the peak of Italy's financial crisis. The crisis escalated in the summer of 2011 when speculative attacks brought the interest rate on Italian bonds at record highs, jeopardizing the government's capacity to finance its operations and exacerbating financial market instability. Italy's substantial national debt, coupled with government's reluctance to raise taxes, meant the requirement of borrowing to finance economic stimulus measures. Prime Minister Berlusconi's inability to effectively manage the crisis culminated in his resignation on November 12, 2011. Four days later, a technocratic government led by Professor Mario Monti, a former European Union (EU) competition commissioner, took the reins with bipartisan support. This abrupt shift in power led to Berlusconi's loss of influence over public TV, with directors being replaced by the new government.

Data

Teche RAI data

The data, obtained from RAI historical archive, contain verbatim transcripts of all national newscasts aired between 2010 and 2014. The corpus is a product of an advanced transcription system (ANTS) developed by RAI, which employs speech recognition tailored to the speaker's voice footprint and yielding an impressing accuracy rate of about 90%. The transcriptions are segmented by news story, with metadata including channel, topic, date, and timing. Typically, each channel airs three 30-minute newscasts daily (morning, noon, and evening). The data include about 20,000 hours of broadcasting content, divided into 388,460 news story segments.

A distinctive aspect of the Teche RAI dataset is the exclusion of all direct politicians' interventions, ensuring that our analysis reflects solely the journalistic coverage and commentary of the news. While the presence of political leaders is undoubtedly important, its direct impact effect is well-established in the literature (Durante and Knight, Reference Durante and Knight2012; Bellucci and De Angelis, Reference Bellucci and De Angelis2013). Our focus is on the subtler dynamics of political news removal and replacement within newscasts, rather than overt strategic communication by political leaders. This characteristic of the Teche RAI data allows for a robust test of our hypothesis, isolating the effect of variations in news content. Descriptive statistics of the dataset are detailed in Table B.1 in the online Appendix, which includes information on newscast titles, media group affiliations, edition times, segment counts, segments per edition, and segment durations.

Italian National Election Studies

The ITANES panel data for 2011–2012 collected a representative sample of Italian voters, with data collected over five waves from February 2011 to June 2012. The dataset includes general demographic information, various batteries of questions relating political attitudes and behavior and, crucially, detailed questions about respondents' media consumption, including reported media usage, frequency of media usage, and preferred sources of information all including TV channels and news programs. Descriptive statistics presented in Table B.2 in the online Appendix show that ITANES respondents, similarly to the broader Italian population, are predominantly TV-oriented, with a majority citing TV as their primary source information.

Unsupervised scaling of news media content

To quantify the content of news broadcasts, we employ an unsupervised text scaling technique known as WORDFISH (Slapin and Proksch, Reference Slapin and Proksch2008). This model posits that variations in word frequencies across different newscasts can be attributed to a latent, continuous distribution, reflecting underlying content dimensions. The WORDFISH algorithm operates under the “naive Bayes” framework, treating the text as a “bag of words” where the occurrence of each word (unigram) is independent of others.

Specifically, WORDFISH assumes that the frequency of each unigram follows a Poisson distribution, parameterized by λ, which is modeled as:

where j indexes words, i indexes TV news programs, and t indexes the time of the newscast. The matrix Y ijt represents the data, with rows corresponding to documents (newscasts) and columns to words. Each matrix cell indicates the frequency of a given word in a particular newscast.

The λ ijt parameter is modeled as a function of four latent quantities: α it is a document-level fixed-effect term controlling for document length; ψ j is a word-specific fixed-effect term controlling for the overall frequency of the words; β j captures the ability of word j to discriminate across document positions; and ω it is our primary quantity of interest measuring the latent position of news transcript it in the news' content space.

In other words, WORDFISH partitions the total variation in word frequencies into words' general usage rate, differential length of the documents, and an informative residual component relating the news content between two poles of the latent news space continuum.Footnote 2 All parameters are simultaneously estimated via expectation maximization algorithm.Footnote 3 For reasons of computational efficiency, and after tests showing no substantial loss in the statistical precision, we aggregate the news segments by day. In sum, the resulting ω scores represent pure content-based positions over a latent space of televised news.

In terms of the substantive nature of the news latent space, our procedure does not require arbitrary categorizations and remains agnostic regarding which dimension will differentiate the news in our corpus. Several studies have shown that political news can be divided between politically relevant “hard” news content, covering socially relevant, political, and economic events, and “soft” news stories, including gossip, personally relevant contents, leisure, and sports (Zaller, Reference Zaller1999; Prior, Reference Prior2011). Thus, we expected our estimated content scores to map into this hard–soft news dimension rather than on an ideological continuum.

Our content-based scaling measure is continuous and centered around zero, leading to straightforward categorization for validation. This measure adeptly captures the essence of “hard” news across diverse segments, including those not traditionally associated with politics. For instance, it can discern the political implications in sports coverage, such as the political gestures of athletes, classifying them appropriately as “hard” news. Moreover, it differentiates broad topics such as crime stories separating entertainment-focused crime stories from policy-oriented news segments covering more serious cases like corruption.

Applying unsupervised scaling on Teche RAI data, we produce content scores from all national broadcasts, delivering a clear picture of the overall news environment across channels. This is a key advantage over studies identifying media effects relating one specific news source (DellaVigna and Kaplan, Reference DellaVigna and Kaplan2007; Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Karlan and Bergan2009). Content scores can be precisely compared in terms of similarity across and within networks over time, allowing to easily match this information with survey data. We warn, however, that this approach may not be optimal for certain news formats blending elements of entertainment with news reporting: the application of WORDFISH to our corpus is grounded in the specific nature of our data – traditional newscast transcripts that do not feature “infotainment” content. This distinction is critical, as our corpus is homogeneous in type and reflective of a conventional news format where hard and soft news are more distinctly demarcated.

Results

Validation of the news content scores

Differently from classic text scaling performed on party manifestos, we cannot rely on external classifications to assess the estimated scores. We therefore designed an encompassing validation strategy in four steps. First, we contrast the document-level ω scores with the word-level β scores most representative of the two poles of the news latent space. Second, we calculate network-level average news scores to assess the scores in the light of our substantive knowledge of the different profiles of the channels. Third, we rely on metadata describing the topic of the news and calculate average scores for meaningful topics (entertainment and sport, political and economic news). Finally, we perform a structural topic model (STM) to identify the latent topics in the corpus and show the distribution of the news scores by identified topic.

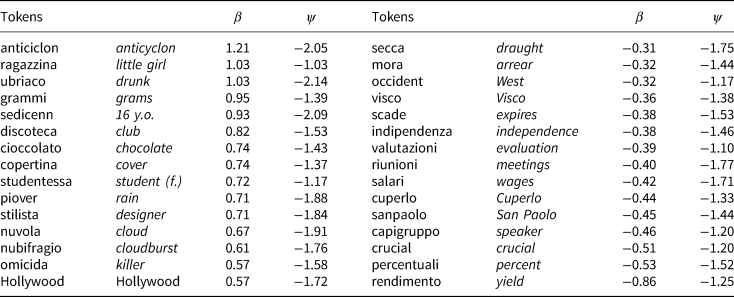

Validation using word-level β scores

The words with the highest and lowest β scores are those that most distinctively characterize variation in the positioning of the newscasts (ω scores). The distribution of the β scores is approximately normally distributed, and therefore the most distinctive words will be located at the tails of this distribution. Table 2 presents the top 15 words for each side, with their associated β and ψ scores. Following a validation practice similar to other unsupervised models, such as topic modeling (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Stewart, Tingley, Lucas, Leder-Luis, Gadarian, Albertson and Rand2014), we can assess the news content scores by inspecting the words associated with the extremes points on the scale: high (positive) β scores appear to be indicative of an entertainment tone, referring to stories with personal relevance, weather reports, and gossip. In contrast, words with a low (negative) β scores are associated with more serious and policy-relevant news content, including economic and political news reports.

Table 2. List of top 15 words associated with positive and negative β scores

Note: The table reports the results from the estimation of word-specific parameters. β scores identify variation across the one-dimensional scale, from soft news (positive scores) to hard news (negative scores). ψ scores evaluate the relative importance of each word in discriminating across actors.

aVincenzo Visco, then head of the Bank of Italy.

bGianni Cuperlo, then head of the Democratic Party.

cBanca San Paolo, a national bank involved in a scandal.

Validation aggregating document-level scores by TV network

We aggregate the document-level ω scores at the network level with the expectation of finding more hard news contents on the RAI newscasts, as compared to Mediaset. Furthermore, we expect news from Italia 1 (BERLUSCONI3) to have disproportionately more soft news, and news from RAI3 (PUBLIC3) to have more hard news. The average values of the estimated scores across network are respectively: −0.113 (PUBLIC1), −0.071 (PUBLIC2), −0.739 (PUBLIC3), 0.927 (BERLUSCONI1), 0.460 (BERLUSCONI2), 1.380 (BERLUSCONI3). Such distribution of scores – negative for RAI (public) channels and positive for Mediaset – mirrors a news configuration familiar to other countries, where public networks provide more serious and policy-relevant content, and private networks are more entertainment-oriented. Furthermore, the fact that the average content score for BERLUSCONI1 (Rete 4) is lower than for BERLUSCONI3 (Italia 1) is indicative that our content scores are not directly measuring an ideological or political leaning, since Rete 4 has been historically the most supportive for Berlusconi, while BERLUSCONI3 (Italia 1) is the most entertainment-oriented channel.

Validation using Teche RAI topic metadata

Teche RAI data provide a metadata tag labeling the news issue domain. These tags, generated by an earlier algorithm, may not always be accurate and tend to categorize news into broad domains, encompassing six categories: crime and current affairs, lifestyle, legal affairs, foreign affairs, politics, and economics. To validate our content scaling scores, we examined the distribution of these scores within the specified macro-topics. For each edition of the news, we computed the proportion of segments falling into each macro-topic and plotted these proportions against their corresponding content scaling scores. Figure 1 presents a scatter plot for each macro-topic, with an overlaid box plot to highlight the distribution of content scores. High ω news scores characterize news segments with a high proportion of crime and current events stories, as well as lifestyle stories. On the contrary, low scores were estimated for news segments containing mainly legal and justice affairs, economic affairs, and political news.

Figure 1. Validating ω scores with Teche RAI issue domains.

Validation through topic modeling

To further substantiate our claim that news content scores map the soft–hard news continuum, we employed an STM. STM allows for the identification of latent topics by capturing the co-occurrence patterns of words across documents. We identified 20 distinct latent topics, and then inspected the distributions of the ω news scores for those news segments where each of the latent topics had the highest prevalence compared to the other topics. The resulting plot, illustrated in Figure 2, broadly confirms the coherence of our measure, demonstrating that soft (hard) news latent topics are characterized by a higher (lower) ω score.Footnote 4, Footnote 5

Figure 2. Validating ω scores with topic modeling.

Effects of political influence on news media coverage

Our analysis of the estimated news content scores reveals a discernible pattern in the distribution of news content, which oscillates between “hard” news, encompassing parliamentary and economic reporting, and “soft” news, such as celebrity gossip, crime, and weather stories. Figure 3 presents the temporal evolution of these scores within the time frame of our study.

Figure 3. Content scores by network, June 2011–May 2014.

The dashed line in Figure 3 marks November 12, 2011, the date of Berlusconi's resignation. The time series of the weekly ω scores indicates a notable decline in news content scores for RAI subsequent to this political event, suggesting a shift toward more “hard” news coverage. In contrast, Mediaset's scores do not exhibit a similar pattern, implying a relative consistency in their news content. The visibly spike in positive news scores on RAI channels in late February 2012 corresponds with the broadcast of the Italian national music contest (Festival di Sanremo), an anticipated annual event.

It is important to note that these shifts in news content scores are not simply reflections of the financial climate. The interest rates on Italian bonds reached a peak prior to Berlusconi's resignation and, while they remained elevated, they did not surpass previous levels during the period under study. This observation strengthens the argument that the changes in RAI's news content scores are more plausibly attributed to alterations in political influence rather than fluctuations in financial conditions.

To systematically test our hypothesis that Berlusconi's government exerted political influence on public Italian TV to prioritize soft news coverage we rely on a difference-in-differences approach. We compare variations in news content on RAI and Mediaset newscasts before and after Berlusconi's tenure. We posit that RAI newscasts were more vulnerable to shifts in political influence compared to Mediaset, which was ostensibly insulated from the political upheaval.

Berlusconi's unforeseen departure from office, precipitated by factors extrinsic to the media domain, is treated as an exogenous shock that diminished his influence over public TV. Under the premise that, absent this political pressure, the proportion of “hard” news on public TV would have mirrored the patterns observed during the pre-treatment phase, we can isolate the extent of political influence. However, a potential caveat in this design is the assumption that Mediaset's editorial strategy remained constant irrespective of Berlusconi's capacity to affect public channels. Should Mediaset's editorial decisions be reactive to the treatment of public channels, it would suggest that the potential outcomes are not invariant to the allocation of treatment.

To address such concerns, we employ a within-subject design that treats the timing of the intervention as quasi-random. This allows us to compare outcomes within each channel, holding constant channel-specific effects. To formally assess the impact of Berlusconi's departure on RAI's news production, we estimate the following difference-in-differences regression model:

Here, Y ist represents the ω news content scores for channel i in group s and at time t. λ RAI is a binary indicator for the public broadcaster RAI, and Postt is a binary indicator for news aired after Berlusconi's resignation on November 12, 2011. The coefficient of interest, β, captures the differential effect of Berlusconi's government's end on the content of RAI's news. To account for potential non-linear time trends, we incorporate cubic B-splines with monthly knots, and we include channel-specific fixed-effects γ i to control for unobserved heterogeneity at the channel level. Figure 4 provides a graphical illustration of the parallel trend assumption. Coefficients represent results from Equation (4) with 95% confidence interval for 14 periods (months) lags and leads.

Figure 4. Impact of Berlusconi's resignation on RAI news content: a time-series analysis.

The regression results, detailed in Table 3, indicate a significant decrease in the ω scores post resignations. Specifically, the scores dropped by an average of 0.095 points, corresponding to 0.139 standard deviations. These findings remain robust when controlling for potential confounding events through the inclusion of bi-weekly splines. Model 3 in the table disaggregates the effect by public channel. As hypothesized, the most robust effect is observed for RAI1 (PUBLIC1), the channel traditionally aligned with the incumbent Prime Minister's party. This channel experienced a directorial change shortly after the government transition, which likely contributed to the observed shift in content. In contrast, RAI3 (PUBLIC3), known for its left-wing orientation, did not exhibit significant changes.Footnote 6

Table 3. Difference-in-differences estimates

Note: Standard errors are clustered at the news segment level. Significance stars: *P < 0.1; **P < 0.05; ***P < 0.01. Splines are calculated using bi-weekly knots.

To test the parallel trend assumption of our difference-in-differences design, we conducted an analysis of the co-movement of news content scores between public and private TV. This involved estimating month-specific period effects using the following regression model:

The results, shown in Figure 4, confirm that the content scores were co-moving before Berlusconi's resignation. Notably, significant differences emerged only after Berlusconi's resignation, aligning with our expectations and lending support to the parallel trend assumption.

Agenda-setting and framing effects: exploring the mechanism of political influence

We further explore the mechanisms underlying content differentiation by inspecting the news stories within-topic. By analyzing the language employed across different newscasts on the same news topic, we discern variations in framing – how the same subject matter is presented differently across channels. This analysis of framing effects complements the assessment of agenda-setting effects, which we define in terms of the relative airtime allocated to various news topics. We use the Teche RAI meta-data topic tags to select the hard news stories (political and economic affairs). For each topic, we conduct a two-step analysis: first, we recalculate the ω content scores to identify potential differences in language use within-topic among different channels. Subsequently, we quantify and compare the cumulative airtime devoted to each topic across channels to identify any discrepancies in the volume of coverage.

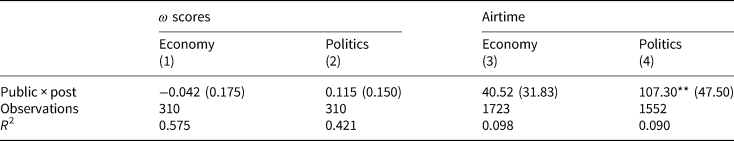

Table 4 presents models of the news content (ω) scores for economic and political news (models 1 and 2), and for the coverage of economic and political news in seconds per day (models 3 and 4). We find no evidence of language change for economic or political news after Berlusconi's resignation. On the contrary, column 3 shows a slight increase in daily airtime of about 40 seconds, although the estimate is not statistically significant, and model 4 shows significant and substantial differences in the airtime coverage devoted to political news: public TV increased the time dedicated to politics after Berlusconi resigned for about 107 seconds daily. These estimates corroborate the interpretation that during Berlusconi's tenure, public TV significantly under-reported political news, clarifying that political influence was not exerted through changes in the framing of political news but, rather, through political news removal, with the consequent setting of the agenda on softer issues.

Table 4. Framing vs. agenda-setting

Note: The table reports estimates of a difference-in-differences specification, with as dependent variable the estimated ω-scores or the airtime for the subset of news stories dealing with economic or political issues. Observations are aggregated at the weekly level to estimate ω-scores. Estimates are in daily seconds for airtime. Linear regression coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. Significance stars: *P < 0.1; **P < 0.05; ***P < 0.01.

Effects of media on public opinion

We conclude our analyses assessing the impact that changes in news content have on public opinion. To this end, we integrated our estimated ω news content scores with a representative panel data of Italian voters from ITANES. This dataset provides self-reported measures of media consumption, including the most preferred news channel and the frequency of news consumption.

We operationalize this by associating each respondent's reported preferred news program with the corresponding ω news score. Specifically, we match the news program indicated in each wave of the panel data, with the mean ω score calculated for the 30-day period preceding the interview date of the respondent, the 30 days before the day of the respondent's interview. The monthly aggregation is intended to isolate the news signal out of the noisy fluctuations arising due to daily events variability. Our identification strategy assumes that viewers can exercise discretion in selecting their news source, but cannot influence or select news contents besides for the news channel.Footnote 7 The statistical model includes wave and channel fixed-effects, and it is specified as follows:

where the dependent variables include the support for Berlusconi's party, and the overall evaluation of the government measured on a 0–10 scale. The main coefficient of interest is β, capturing the within-individual effect of changes in the ω content scores. Controls (X it) include time-varying measures for party ID, self-reported position on a left-right scale, and monthly splines. The δ coefficient controls for the effect of the favorite newscast on political attitudes, thus controlling for a primary source of selection bias. By additionally including individual fixed-effects γ i, we are estimating how a change in news coverage affected each individual, accounting for all observable and unobservable time-invariant individual characteristics that may further induce self-selection into a particular news stream. We finally also control for time fixed-effects to account for contextual factors.

We estimate three model specifications using the propensity as dependent variable to vote for Berlusconi's partyFootnote 8 (models 1–3) and one model for the overall support for the incumbent government. Model 1 reports the ω content score coefficient controlling for wave and individual fixed-effects. Model 2 selects the sample of voters that did not declare a change in preferred newscast within our sample: these non-switchers, reporting consistent exposure, cannot have self-selected, switching news source, into more aligned news sources as a consequence of changes in the news contents. Finally, model 3 provides a placebo test by selecting the sample of respondents that did not report “television newscasts” as their first or second source of political information. All model specifications include individual fixed-effects, and control for self-reported political affiliation and left-right ideology on a Likert scale.Footnote 9

Table 5 reports the estimates: in the two valid models (1 and 2), variation in the content scores toward soft news has a positive and significant impact on the electoral support for Berlusconi's party: one standard deviation increase in the content toward softer news is estimated to increase the average propensity to vote for Berlusconi by 0.049 standard deviations. The effect is substantially significant, corresponding to about one-fourth of the party identification coefficient. The estimates are similar for non-switchers. Furthermore, we do not find an significant effect for the placebo test: while the subset of individuals not watching TV for news is smaller, our estimates are unlikely to be determined by a lack of power as the sample size remains significant, and standard errors are similar to the other model specifications. In model 4, we expand the analysis considering the overall support for Berlusconi's government.Footnote 10 Estimates show a substantial effect on Berlusconi's government support, although the coefficient is only significant at the 10% confidence level. Overall, the estimates converge in supporting the view that variation in media content toward softer contents has built political support for Berlusconi.

Table 5. ω score impact on public opinion

Note: The table reports ordinary least-squares individual fixed-effect estimates. The dependent variable is the intensity of support for Berlusconi's party and government on a scale from 0 to 10. Controls include time-varying controls for party ID, self-reported position on a left-right scale, and monthly splines. *P < 0.1; **P < 0.05; ***P < 0.01. Estimates report coefficients from standardized variable, and are interpreted as standard deviations.

In presenting these findings, we have to acknowledge some limitations. First, we lack measures of frequency of news consumption at the newscast level, so we are unable to investigate the effect of ω scores in relation to the intensity of viewership, which could lead to interpret our estimates as intention-to-treat effects. Second, we are unable to differentiate between two non-mutually exclusive mechanisms. Newscasts are bound to an airtime of about 30 min per edition. Thus, editorial decisions may reduce the coverage on a particular topic, operating a substitution with different topics. Our study cannot differentiate between the effect of the heightened coverage of soft news vis-a-vis the reduction in hard news. We speculate that the omission of hard news operates reducing the perceived salience of political affairs and the financial crisis, although it is equally possible that soft news, particularly those involving crime episodes, may have reinforced the demand for law and order policies traditionally associated with right-wing parties. Both mechanisms may have increased political support for Berlusconi, and we are unable to ascertain which, if only one, impacts more public opinion formation.

Conclusions

Our investigation unveils previously disregarded elements of political control on public broadcasting focusing on the case of Italy's 2011 economic turmoil. The quantitative evidence demonstrates a strategic transition from hard news to soft news contents on public TV during Berlusconi's tenure. This shift away from essential political discourse, with an average decrease of 107 seconds daily, carries potential implications for public awareness and opinion formation, consequently tilting the electoral prospects toward the ruling party.

Our paper makes three main contributions. First, we apply text scaling to derive and validate a robust measure of news content mapping the latent space ranging from hard news to soft news. Second, we shed light on a mechanism of political influence on media that involves the omission of politically relevant information, whereas previous studies had focused on ideological bias and framing alterations in political news. Third, we offer fresh evidence underscoring the influence of news media on public perceptions and electoral preferences thereby underpinning the essential role of independent public media for an informed and unbiased public opinion.

Methodologically, we introduce an innovative application of unsupervised text scaling to TV news, identifying a latent space of news contents ranging from hard to soft stories. This application can enhance our analytical capacity to identify shifts in media content that were previously unnoticed, opening new avenues for examining political alterations in media narratives that bear significance for the public discourse.

The evidence uncovered has significant implications beyond the Italian experience, confronting a core pillar of democratic integrity: the autonomy of the press in the face of political influence. Our findings are therefore broadly significant for European press freedom, as the Italian case serves as an indicator for subtle mechanisms undermining the fair and thorough account of political and economic events that is vital to a healthy electoral democracy. As we demonstrate, there is no need for overt censorship when political influence can insidiously operate through content replacement – a tactic that could be emulated in other democratic contexts.

In the age of Artificial Intelligence and algorithmically generated and curated news streams, the significance of an independent public TV as a source of trustworthy information remains paramount. However, as shown by the recent EU investigation into Twitter/X over alleged disinformation campaigns, digital media lack the credibility of regulated news networks, and can expose unaware citizens to filter bubbles and misinformation cascades (Newman, Reference Newman2023). Moreover, the erosion of news engagement and trust is alarmingly linked to the rise of skepticism that propagates “post-truth” attitudes within public discourse.

Against this backdrop, fortifying the trust between public media and public opinions is crucial. This trust is a vital defense against the unrestrained tide of AI-generated political and a foundational pillar for an effective electoral democracy. A robust strategy to reinforce the trust between public media and public opinions must integrate two essential elements. On the part of public media, it is imperative to have stringent regulatory oversight and robust legal frameworks that safeguard press freedom and independence. Such measures are vital for ensuring fair and accurate reporting of events of social significance, thus mitigating the risk of political interference in editorial judgments. On the audience's side, it is equally imperative to cultivate a culture of news media discernment and critical thinking. This approach empowers viewers and readers, equipping them with the necessary media literacy skills to critically evaluate instances of political bias, including hard news displacement, logical inconsistencies, and the use of emotive language intended to manipulate public opinion. Only through such concerted efforts can we aim at preserving the foundations of democratic discourse and ensure that the electorate remains informed, engaged, and resilient in the face of political and technological challenges.

Funding

The research has been funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF-Ambizione grant 201817).

Data

The replication dataset is available at http://thedata.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/ipsr-risp.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2023.32

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Shanker Satyanath, Cyrus Samii, Pablo Querubin, David Stasavage, Alexander Trechsel, Hanspeter Kriesi, Paolo Bellucci, Amy Catalinac, Arturas Rozenas, Justin Grimmer, John Marshall, Julia Cagé, Andrea Prat, Eliana La Ferrara, Andy Guess, Pablo Barberá, Paolo Pinotti, Neal Beck, and seminar participants at NYU, EUI, University of Lucerne, MPSA, EPSA, and fRDB fellow workshops. We appreciate Teche RAI for sharing their data. All errors are our own.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.

Author Contribution

Both authors contributed equally to research design, data analysis, and drafting the article.