Introduction

In 2023, Freedom House recorded the 18th consecutive year of decline in global freedom (Freedom in the World, 2024). During the same year, Varieties of Democracy estimates that the average level of democracy in the world returned to 1998-levels (Democracy Report, 2024). The publication of these data will likely fuel the ongoing debate on the global state of democracy, which is often depicted as a clash between demo-pessimists, who believe that the world has entered a phase of democratic recession, and demo-optimists, who continue to see democracy as healthy overall. However, this polarization between demo-optimists and demo-pessimists is simplistic and conceals a more articulate debate related not only to ‘how democracy is doing’ but also to which interpretive tool is best suited for this kind of assessment.

For decades, this debate has been informed by the ‘waves (of democratization) and ebbs (of autocratization)’ model proposed in 1991 by Samuel Huntington in The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century, which is still the benchmark for those who venture into the fascinating but arduous task of interpreting global regime trends. Over these years, the ‘waves and ebbs’ model – that is, the idea of an alternation between historical phases during which democracy spreads and retreats – has undergone countless discussions that highlight merits and several limitations, especially concerning its ability to explain the contemporary epoch and, specifically, the three decades following the end of the Cold War. However, thus far, few alternative approaches have been proposed to interpret the global regime trends that have characterized this period.

To contribute to this debate, I bridge scholarship on the late 20th-century transitions from authoritarianism that led only to semi-democratic regimes (Diamond, Reference Diamond2002) and on the more recent processes of backsliding that have resulted in the erosion (yet not the abolishment) of democracy (Lührmann and Lindberg, Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019), and I advance the idea of a ‘great convergence’ towards hybrid regimes. More specifically, I argue that, rather than an alternation between democratization waves and authoritarian ebbs, the three decades that followed the end of the Cold War could be described more fruitfully as a phase characterized by a tendency of both democracies and autocracies to shift towards hybrid forms of political regime that are neither fully democratic nor fully authoritarian.

The remainder of this note reconstructs the debate on regime change as it has evolved since Huntington (Reference Huntington1991), introduces the idea of a ‘great convergence’ and provides supportive descriptive empirical evidence. To summarize, I show that while democratization and autocratization unquestionably represent important phenomena during the post-Cold War epoch, hybridization (i.e. transitions to hybrid regimes) actually represents the prevailing pattern and, for this reason, deserves renewed attention as a distinct process of regime change that may affect both autocratic and democratic regimes.

Surfing waves and ebbs

In 1991, Samuel Huntington published The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century. According to the author, the international diffusion of democracy unfolds neither in a linear and progressive way, nor erratically. Instead, democratization comes in waves, consisting in historical periods during which transitions from non-democratic to democratic regimes significantly outnumber transitions in the opposite direction. Specifically, Huntington identified three main waves of democratization. The first wave developed throughout the 19th and the early 20th centuries. The second wave came on the heels of World War II. The third wave started in the mid-1970s in Southern Europe and subsequently reached Latin America, some Asian countries and Eastern Europe. Importantly, Huntington specified that waves of democratization tend to be followed by ebbs (or reverse waves) of autocratization that bring authoritarianism back in some countries. Both the first wave and the second wave eventually ebbed, between the two world wars and between the late 1950s and early 1970s, respectively.

More than a milestone in the debate on the international diffusion of democracy, Huntington's Third Wave represented a point of no return. The wave metaphor became the lens through which generations of scholars tried to interpret democratization and autocratization trends during the next three decades. For instance, post-Soviet transitions and sub-Saharan multiparty reforms in the 1990s have been depicted as a prosecution of the third wave – or even a ‘fourth wave’ (Doorenspleet, Reference Doorenspleet2005). Similarly, the challenges of consolidation faced by newly established democracies prompted debate regarding whether the third wave was losing momentum and democracy's ability to spread further (Diamond, Reference Diamond1996).

The impact of Huntington's theory is also demonstrated by the criticisms it has received. Some scholars cast doubt on the appropriateness of the wave metaphor by highlighting conceptual and measurement weaknesses. Kurzman (Reference Kurzman1998), for example, traced quite different historical patterns through alternative operationalizations. Paxton (Reference Paxton2000) and Doorenspleet (Reference Doorenspleet2005), in turn, noted that Huntington overlooked political inclusion as a defining feature of democracy. If the extension of suffrage to women and other excluded groups is considered, they argued, several democratic transitions must be post-dated by decades and the counting does not reveal clear waves. Even Moller and Skaaning did not find compelling evidence of democracy's historical tendency to ‘wax and wane in such a consistent manner’ (Reference Moller and Skaaning2013: 106).

Other scholars have questioned the genuine democraticness of several countries that supposedly democratized during the last part of the 20th century (Carothers, Reference Carothers2002). Adjectives have proliferated in the literature to account for the delegative, illiberal or otherwise defective character of many new democracies (Merkel, Reference Merkel2004). Others were more explicit about the non-democratic nature of these regimes variously labelled as hybrid, electoral authoritarian and competitive authoritarian regimes (Diamond, Reference Diamond2002).

Huntington's ‘waves and ebbs’ model survived these criticisms. During the 2010s, it retook centre stage again as the fear arose that the third wave of democratization, similar to previous waves, could be followed by a new authoritarian tide (Plattner, Reference Plattner2015; Lührmann and Lindberg, Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019). As the wave metaphor returned to the spotlight, a new heated debate unfolded. Once again, some scholars argued that the numbers do not actually tally up. Without considering authoritarian reconsolidation in countries that never fully democratized, for instance, a reverse wave of autocratization is not as evident (Levistky and Way, Reference Levitsky and Way2015). Moreover, only a modest decline in the average global level of democracy has occurred (Weitzel et al., Reference Weitzel, Gerring, Pemstein and Skaaning2024) and the period in which autocratization episodes have outnumbered democratic transitions is shorter (and more recent) than initially estimated (Skaaning, Reference Skaaning2020).

For others, the hype surrounding the risk of a global democratic recession is largely due to the use of subjective rather than objective indicators of democracy (Little and Meng, Reference Little and Meng2024). Allegedly, expert evaluations are biased by the ‘bad vibes’ derived from the growing attention of the media to the issue and nostalgia for a recent past that is ‘not as bright as many seem to remember’ (Carothers and Youngs, Reference Carothers and Youngs2017). Because of this ‘misleading picture’ (Little and Meng, Reference Little and Meng2024: 152), analysts tend to see ‘all democracies as potential backsliders’ (Cianetti and Hanley, Reference Cianetti and Hanley2021: 69) and to conflate possibility (that autocratization occurs) with probability, or even reality. However, objective measures are not free from measurement errors (Knutsen et al., Reference Knutsen, Marquardt, Seim, Coppedge, Edgell, Medzihorsky, Pemstein, Teorell, Gerring and Lindberg2024) and may fail to track the low-profile modalities that frequently characterize contemporary autocratizations (Bermeo, Reference Bermeo2016; Miller, Reference Miller2024). Democratic backsliding can be harmful even when outright democratic breakdown does not follow (Hyde and Saunders, Reference Hyde and Saunders2022), and a bit of ‘tyrannophobia’ helps to preserve democracy after all (Ginsburg, Reference Ginsburg2022).

The idea of an ongoing reverse wave is also criticized for being short-sighted. From a longer-term perspective, the global ‘proportion of democracies is close to an all-time high’ (Treisman, Reference Treisman2023: 1943). By putting contemporary events into a broader historical context, moreover, we can make better use of what we learned about democratization and autocratization during the 20th century regarding structural conditions, most notably socioeconomic development (Brownlee and Miao, Reference Brownlee and Miao2022). From this perspective, we should be more surprised by the resilience of several recently democratized states still struggling with poverty and inequality than by the relatively modest number of democratic breakdowns (Levitsky and Way, Reference Levitsky and Way2023). Similarly, we should remember that in several of the most consolidated contemporary democracies the process of democratization was long and punctuated by missteps and failures (Berman, Reference Berman2019).

Finally, according to another group of scholars, we are just missing the point. Regardless of whether an outright wave of autocratization is underway, the phenomenon ‘exists [and] deserves attention’ (Cassani and Tomini, Reference Cassani and Tomini2019: 2). Tracing and naming regime trends is important, but it ‘can obscure as much as it reveals’ (Cianetti and Hanley, Reference Cianetti and Hanley2021: 66) and ‘risks taking the entire discussion down a blind alley’ (Tomini, Reference Tomini2021: 1192). Instead, research on contemporary processes of autocratization should focus on investigating what actually happens in these countries and why, given its consequences for citizens (Bermeo, Reference Bermeo2022; Gorokhovskaia, Reference Gorokhovskaia2024).

A great convergence towards hybrid regimes

A review of the literature shows that the ‘waves and ebbs’ model proposed by Huntington (Reference Huntington1991) has profoundly shaped how scholars interpret contemporary global regime trends, even though many have questioned its explanatory potential, especially with reference to the three decades that followed the end of the Cold War. In most cases, however, detractors have refrained from addressing one important issue: if reality does not fit perfectly into the ‘waves and ebbs’ metaphor and if we should start thinking outside the box of Huntington's framework, can we detect any regularity in the regime changes that characterized the past three decades?

Building on scholars who investigated the outcomes of late 20th-century transitions from authoritarian rule as well as of more recent processes of autocratization (Carothers, Reference Carothers2002; Diamond, Reference Diamond2002; Bermeo, Reference Bermeo2016; Lührmann and Lindberg, Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019), I argue that the proliferation of so-called hybrid regimes is one such regularity. Accordingly, I contend that rather than an alternation between democratization waves and authoritarian ebbs, the three decades that have followed the end of the Cold War could be described more fruitfully as a phase of ‘great convergence’ towards hybrid forms of political regime in which institutional elements typical of democracy and authoritarianism coexist. Specifically, if convergence is a tendency to move ‘from different positions toward some common point’ (Bennett, Reference Bennett1991: 215), according to the proposed interpretation a majority of the transitions that have occurred during the past three decades represent signs of a more general trend leading both democratic and authoritarian regimes (the ‘different positions’) towards the institutionalization of hybrid regimes (the ‘common point’).

A few caveats are in order. First, by proposing an alternative to the ‘waves and ebbs’ model, I do not intend to underestimate the number and meaningfulness of the regime changes that have occurred since the end of the Cold War that other scholars have tried to explain through that model. The difference lies in the interpretation of those events. According to the idea of a great convergence, several of the regime transitions during that period that were described as processes of democratization and autocratization, albeit incomplete, should instead be interpreted as processes of hybridization that from different starting points – autocracy and democracy, respectively – led to similar outcomes, namely, the establishment of hybrid regimes.

Second, the proliferation of hybrid regimes has already been studied, yet mostly as a result of transitions through which some authoritarian regimes introduce some (but not all) institutions typical of democracy (Diamond, Reference Diamond2002). Hybrid regimes have rarely been studied as possible outcomes of transitions from democracy (but see Morlino, Reference Morlino2009: 282). In contrast, the idea of a great convergence depicts a tendency towards hybrid regimes that can affect both authoritarian and democratic regimes. This is a necessary update, given the partial nature of many contemporary processes of autocratization (Bermeo, Reference Bermeo2016; Lührmann and Lindberg, Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019; Cavatorta [Reference Cavatorta2010] made a similar point regarding an ongoing convergence of governance towards de-politicization).

Third, hybrid regimes are inherently ambiguous, as they represent political regimes that can hardly be classified into categories of democracy and autocracy because they are characterized by a mixture of institutional traits typical of both of these regimes. Unsurprisingly, many approaches to define and measure hybrid regimes exist (Cassani, Reference Cassani2014). In the context of this research, the most useful approach is to treat hybrid regimes as a separate intermediate type between ‘full’ democracy and ‘full’ autocracy that includes both defective forms of democracy and electoral and somewhat competitive forms of autocracy (Bogaards, Reference Bogaards2009).

Specifically, a country can be considered democratic if it fulfils Dahl's (Reference Dahl1971) requisites for inclusiveness and competitiveness (most notably, free and fair multiparty universal suffrage elections for both executive and legislative and political freedoms of association, expression and press), if individual rights are protected, and if government power is limited by a system of checks and balances. Under autocracy, in contrast, either government power is not assigned through universal suffrage multiparty elections, or such elections are held but competition is de facto neutralized through severe limitations to political and individual freedoms and/or electoral manipulation. As mixtures of institutional traits typical of both democracy and autocracy, in hybrid regimes government power is vested in officials selected through multiparty universal suffrage elections in which opposition parties are actually able to contest but, at the same time, elections are not entirely fair, political and individual liberties are not fully guaranteed, and/or government power is weakly restricted.

Tracing the great convergence

To test the interpretative potential of the idea of a great convergence towards hybrid regimes, I derive from the above discussion the expectation that, paraphrasing Huntington, since the end of the Cold War transitions to hybrid regimes have significantly outnumbered transitions in other directions, namely, transitions to democracy and to autocracy. The analysis, which has purely descriptive purposes, proceeds as follows.

First, I operationalize democracy, autocracy and hybrid regimes, as defined above. Given that establishing thresholds to separate regime types is a notoriously challenging task that entails some arbitrariness, I illustrate my measurement decisions in detail. In the Supplementary material, moreover, I check the findings' robustness using alternative operational rules and data. The easiest way to measure a tripartite regime typology is through the data annually compiled by Freedom House (FH), which is often criticized but has the merit of adopting a rather conservative approach before recording a change in a country's rating (Gorokhovskaia, Reference Gorokhovskaia2024). Specifically, I classify ‘free’ states as democratic and ‘partly free’ states as hybrid, but only if they hold universal suffrage multiparty elections for both the legislature and the executive. Countries rated as ‘not free’ (which for clarity include electoral regimes in which competition is virtually prohibited, such as Egypt, Russia and Rwanda) and ‘partly free’ countries with non-elected chief executives (e.g. Morocco and Jordan) are coded as autocratic.

Second, I apply these rules to 174 countries (i.e. all independent states, excluding microstates) observed from 1990 to 2023, and track regime transitions every time a change occurs in a country's regime classification. To avoid inflating their number, I do not consider regimes that endure less than 5 years. While demanding (in her seminal research, Geddes [Reference Geddes2003] used a 3-year requirement), this threshold helps to exclude both protracted transitions and failed (or reverted) transitions during which a country's FH score and status could experience multiple changes, at times in opposite directions. Using these rules, I count 156 regime transitions, which I distinguish based on their outcome in transitions to democratic, hybrid and autocratic regimes.

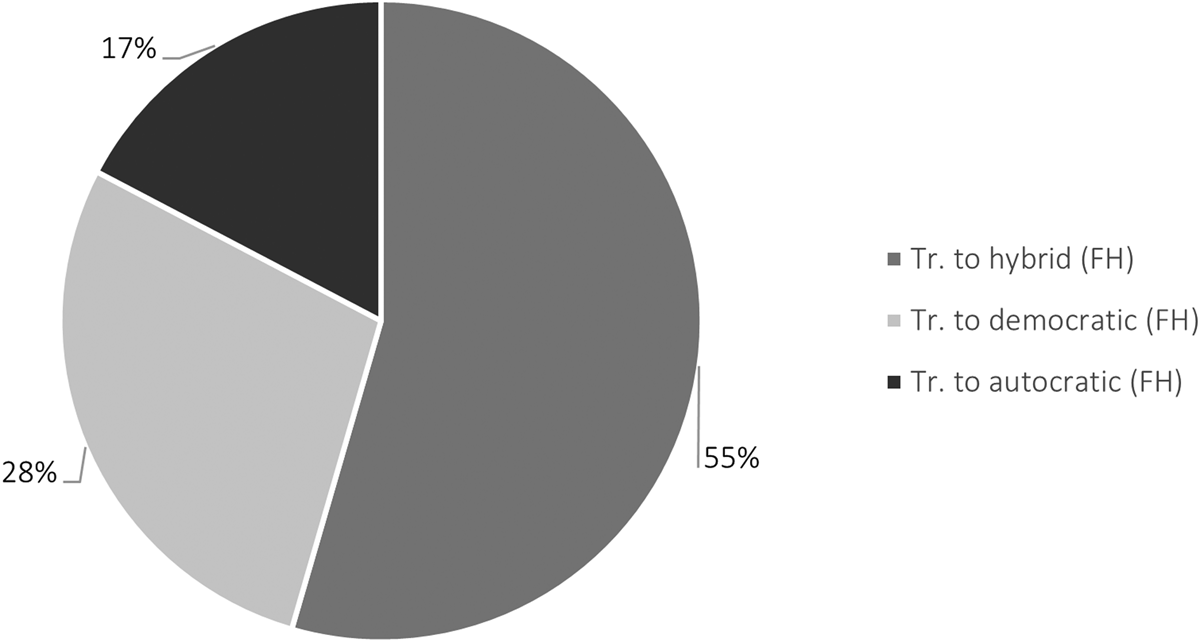

Consistent with the ‘great convergence’ idea, Figure 1 shows that more than half (55%) of the transitions that occurred in the three decades following the end of the Cold War led to the installation of hybrid regimes, ostensibly outnumbering both democratic transitions and autocratic transitions. If we exclude time-censored transitions that occurred after 2019 leading to regimes that cannot fulfil the 5-year duration rule as of the end of 2023, the share of transitions to hybrid regimes is even larger (56%). A closer look at the data shows that sub-Saharan Africa is the region where the majority of transitions to hybrid regimes occurred (40%), followed by the post-Communist region and Asia.

Figure 1. Total regime transitions, 1990–2023.

Notes: Varieties of regime transitions as percentages of total transitions. See also Table 1 in the Supplementary material.

Figure 2 demonstrates that the pattern of convergence towards hybrid regimes prevailed not only during the early post-Cold War period (1990–1999) but also throughout the first quarter of the new century (2000–2023). However, Figure 3 shows that the point of departure of transitions to hybrid regimes has been changing over time. While most of these transitions originated in autocratic regimes (65%), the frequency of democracy-to-hybrid transitions has recently increased significantly: the graph shows that the latter's cumulative share almost doubled between 2009 and 2019.

Figure 2. Regime transitions over time, 1990–2023.

Notes: 5-year moving average of the annual percentage of regime transitions by type. See also Table 2 in the Supplementary Material and Figures A1–A4 in the Appendix.

Figure 3. Democracy-to-hybrid transitions over time, 1990–2023.

Notes: Cumulative percentage of democracy-to-hybrid transitions relative to total transitions to hybrid (democracy-to-hybrid plus autocracy-to-hybrid). See also Table 4 and Figure 6 in the Supplementary Material.

To conclude, a ‘great convergence’ towards hybrid regimes does emerge from the analysis as the main trend of regime change during the three decades that followed the end of the Cold War and as a tendency characterising both democratic and autocratic regimes. Figure 4 shows that, as a consequence of this trend, hybrid regimes currently represent slightly less than one-third of total regimes. Their share increased significantly during the 1990s, and continued to grow throughout the 21st century, peaking in 2019 just before the Covid-19 pandemic, which caused an intensification of repression in non-democratic regimes (Cassani, Reference Cassani2022), and Africa's new wave of military coups (Freedom in the World, 2024). Reassuringly, the above conclusions withstand the employment of different data and operational rules, as detailed in the Supplementary material.

Figure 4. Political regimes over time, 1990–2023.

Notes: Annual percentage of political regimes by type. See also Figures A5–A8 in the Appendix.

Conclusion

Rather than an alternation between democratization waves and authoritarian ebbs, the three decades that followed the end of the Cold War could be described as a phase of regime convergence, that is, a tendency of both democracies and autocracies to shift towards hybrid institutional arrangements. This is demonstrated by the fact that the number of transitions to hybrid regimes significantly exceeds transitions in other directions. Hence, while democratization (i.e. transitions to democracy) and autocratization (i.e. transitions to autocracy) unquestionably represent important phenomena of our epoch, hybridization (i.e. transitions to hybrid regimes) actually represents the prevailing pattern.

For clarity, the proposed image of a great convergence has mainly descriptive power and only applies to a specific and relatively short historical period. Moreover, the tripartite regime typology that I employ is only one of the possible approaches to classifying political regimes, which range from simpler dichotomies to more complex taxonomies encompassing subtypes of democratic and non-democratic regimes. As an attempt to ‘think outside the box’ of the wave metaphor, however, the analysis presented in this note contributes to moving beyond Huntington's model and the criticisms it has received. Most importantly, it highlights hybridization as an empirically relevant process of regime change that is distinct from both democratization and autocratization, and that could affect autocracies and democracies alike.

Acknowledging hybridization's otherness paves the way for new research on, for instance, similarities and differences in the determinants of the institutionalization of hybrid regimes across previously autocratic and democratic countries. Moreover, by distinguishing hybridization from both democratization and autocratization, we can gain a clearer view of the challenges facing the international diffusion of democracy, including its promotion and protection. Future research should also investigate how the trend of convergence towards hybrid regimes that has characterized the past three decades will evolve. In 2024, more than half of the world's population is expected to go to the polls. Some of these elections will test hybrid regimes' level of consolidation. Others may represent either the beginning or the continuation of hybridization processes that will bring about new hybrid regimes. Finally, recognising the proliferation of hybrid regimes may shape the way we interpret the transformations the international arena is currently experiencing. The re-intensification of great power competition, marked by a growing ideological confrontation between democratic and autocratic powers, will likely increase the strategic value of states with hybrid regimes as partners and allies, and thus the leverage of these regimes in the international system.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any public or private funding agency.

Data

The replication dataset is available at http://thedata.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/ipsr-risp

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2024.15

Competing interests

The author declares none.