Introduction

Deciding how to distribute public money among different policy programmes is the essence of governing, and it is hardly surprising that this topic attracts so much attention. Political scientists and economists have been incessantly debating the reasons for different patterns of public spending since the 1970s. The hypothesis based on the influence of partisan ideology on the outcomes of budgetary process is part of the broader debate on whether ‘parties matter’ in influencing public policy (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt1996), which is widely studied by scholars owing to its close connection with the normative theory of democracy.

The role of ideology has attracted considerable attention since the 1970s, when the first works based on the partisan theory of governmental expenditure argued that left-wing governments were more inclined towards deficit spending in order to reduce unemployment, but at the price of generating inflation (Hibbs, Reference Hibbs1977). This argument is based on the reasonable assumption that left-wing and right-wing governments adopt policies in keeping with the preferences and interests of their supporters, but it has also come in for considerable criticism both for its theoretical weaknesses and its rather mixed empirical findings. Three arguments, developed during the last two decades, pose serious challenges to the classical version of the partisan theory. First, several authors have emphasized the impact of a set of institutional features, for instance electoral rules and parliamentary procedures, on parties’ policy positions and the mutable nature of the relationship between parties and voters (for a comprehensive review see Häusermann, Picot and Geering, Reference Häusermann, Picot and Geering2013). Second, a radical critique of the partisan theory has been submitted by scholars engaged with the study of policy agendas, for whom policy change is better explained by attention shifts than by party ideology (Baumgartner and Jones, Reference Baumgartner, Foucault and François1993; Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner and Jones2009). Finally, it is argued that past differences between left and right have finally been bridged by the international competition engendered by globalization (Mair, Reference Mair2009).

Besides the re-discussion of the partisan theory in a more complete and adequate speculative framework, studying the relation between party preferences and public expenditures looks particularly important in the present historical conjuncture (Potrafke, Reference Potrafke2009). Indeed, the need of contemporary democracies (especially those within the EU reality) to restore fiscal balance imposes a serious obstacle for parties to implement their electoral pledges. Under the pressure of globalization, governing parties have downplayed their claim to representation in favour of responsibility (Mair, Reference Mair2009). Finding that a relation between partisan preferences and the distribution of public expenditure exists in Italy, where the need to keep the deficit under control is especially important, would be a relevant result for the more general debate on the partisan theory.

The main contribution the present article purports to make is therefore to show that the partisan theory and the approach based on attention shifts should not be treated as alternative explanations of public spending changes. Rather, we would argue that they should be seen as complementary, because parties can be seen as generators of attention shifts. Both left-right ideology and issue prioritization can be seen as indicators of party preferences, though they probably measure two different aspects of them. The ‘logic of attention’ approach can be seen as an evolution of the partisan theory for two reasons. First, it offers a theoretically grounded explanation of why certain simplistic versions of the partisan theory fail to explain policy change. Second, it highlights which features of partisan politics really matter.

This is what we aim to achieve in this long-term analysis of the Italian case. The underlying objective is to understand to what extent partisan theory and the policy agenda approach based on the logic of attention can be considered as complementary explanatory arguments, when trying to understand the way that different governments decide to cut, or to increase, public spending. Hence, the focus here will be on spending on several programmatic functions, such as welfare, education, public order, and defence, that are given a measure of attention in the parties’ manifestos. Those policy issues are also easily related to government ideology, and so clear-cut hypotheses about the expected impact of left- and right-wing governments may be formulated.

We will start by discussing the logic of partisan theory and the policy agenda approach, attempting to show how these two approaches are not necessarily incompatible. Second, we will argue that Italy, due to its long experience of turbulent public finance sector and to the external constraints imposed by the European Monetary Union, can be seen as an interesting case in our search for a robust check by which to examine whether governments’ political colours and shifts in policy attention actually make any significant difference. We will then describe the sources and operationalization of our dependent and independent variables, and employ regression models introducing, in turn, the left-right dimension and the attention paid to each policy by the governing parties. The insights derived from the veto player theory will also be included in order to refine the traditional version of the partisan theory. We then look at the main findings of this study, which may be summarized as follows: in two of the four policy sectors that make up our empirical analysis, the aforementioned theories can explain policy change. Attention to different policies is often correlated with spending changes. Cabinet ideology, measured on the traditional left-right dimension, is only related to budgetary changes when the ideological polarization of governing parties is taken into account. These findings lead us to a discussion of several implications in the conclusive section of the paper, where we argue that the partisan theory and the logic of attention should be considered together because they tap into two complementary aspects of party preferences.

The theoretical argument

The studies stressing some impact of the partisan identity on public spending are numerous and rather assorted in their implications. However, it is hardly surprising that a large part of the literature is generally associated with the partisan theory, given that political parties are vital actors in any modern democracy, and that the size and distribution of public spending is one of the main outcomes of political decisions. The assumption that parties have different preferences regarding the size of government spending, and that once in government they can actually implement their political programmes, in other words, that parties-do-matter, is important for democratic theory. Classical partisan theory is based on the idea that parties compete for votes across a left-right political spectrum (Downs, Reference Downs1957). Left-wing voters and right-wing voters differ in their desired degree of state economic intervention, with left wingers demanding substantial government intervention and the redistribution of wealth, while right wingers demand limited state intervention in the economy. The seminal study by Hibbs (Reference Hibbs1977) has been followed by various works on the effect of partisanship. Looking at overall government spending in 18 countries between 1962 and 1991, Blais et al. (Reference Blais, Blake and Dion1993, Reference Blais, Blake and Dion1996) found that spending tends to increase more under left-wing governments, though the difference observed was rather small. Similar conclusions have been reached by Cusack (Reference Cusack1997), who employed a similar research design but a more comprehensive model.

This classical version of the partisan theory has been criticized on many grounds. At the theoretical level, the idea that left-wing parties should be always more willing to increase government intervention and welfare spending has been questioned (Cowen and Sutter, Reference Cowen and Sutter1998; Tavares, Reference Tavares2004). With regard to the empirical findings of previous studies of the relationship between party ideology and public spending, such studies may be roughly divided into three groups: those confirming a strict correlation between party ideology and public spending, those producing mixed findings, and those finding no relationship at all. In a case study on public spending in France, Baumgartner et al. (Reference Baumgartner and Jones2009) found that the expansion of the size of government was unrelated to the political colour of the President or the Prime Minister. The simplest version of the partisan theory lost considerable credibility when a meta-analysis including all the major cross-country quantitative studies carried out up to 2000, found no support for the idea that left- and right-wing governments consistently differ with regard to their policies (Imbeau et al., Reference Imbeau, Pétry and Lamari2001).

According to Garrett and Lange (Reference Garrett and Lange1991), the empirical weakness of partisan theory casts something of a shadow over the responsible party model theory, which has not only an explanatory role but also a strong normative value. If electoral outcome does not affect how public money is spent, then why should citizens bother to vote? Indeed, some authors claim that even through the left/right factor may have had an impact in the past, the current level of international competition caused by globalization has left governments with virtually no room for manoeuvre. Others have adopted a less pessimistic view, arguing that parties still matter, but in ways that are more complex and subtle than is assumed by the over-simplistic version of the party mandate theory (King et al., Reference King, Laver, Hofferbert, Budge and McDonald1993). Notwithstanding the theoretical and empirical weaknesses of the traditional partisan theory, the literature on public expenditures determinants is still rich in examples where the mere presence of left (or right) parties in government is expected to produce significant policy changes (Potrafke, Reference Potrafke2010; Efthyvoulou, Reference Efthyvoulou2011).

The other pillar supporting our theoretical argument is the ‘logic of attention’, which has emerged as a broad explanatory argument from the work of the ‘agenda scholars’ working in different policy areas. As their first studies on budgets, agenda scholars (Jones and Baumgartner, Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005b; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Baumgartner, Breunig, Wlezien, Soroka, Foucault, François, Green-Pedersen, Koski, John, Mortensen, Varone and Walgrave2009; Breunig, Reference Breunig2011) do not question the assumption that parties have different preferences regarding public spending. Rather, when trying to make sense of the yearly changes in budget authority for different policies, Jones and Baumgartner (Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005a) admit that most changes can only be explained retrospectively, and cannot be predicted as they are the result of the complex interaction of various factors. The basic foundations of this perspective rest on how the political system processes information, transforming the inputs (signals) received from outside into outputs (policy decisions) (Jones and Baumgartner, Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005b). Political systems are characterized by a considerable level of friction, and consequently they tend to treat signals (information) in a disproportionate way. There are two kinds of mechanism that render proportionate responses impossible. First, policy makers formulate a limited number of priorities, and focus their attempts to change the status quo on a few areas only. Cognitive limits are intrinsic to human beings (Jones, Reference Jones2001): the outside world sends a constant stream of signals, but human beings’ capacity to process them is limited. As a consequence, policy makers can only deal with a limited number of problems at any one time. The second source of friction lies with institutions.Footnote 1 Both cognitive and institutional forms of friction operate as retarding forces: change only happens when the force of the signals exceeds the resistance constituted by the friction. All inputs below a certain level of intensity are not prioritized, and are not capable of producing any change in the ways that public money is spent. One important implication of this argument is that changes in governments’ priorities, rather than in their ideology, are more likely to trigger a change in spending. In a comparative study of Denmark, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States, Breunig (Reference Breunig2011) looks at the impact both of institutional costs and of attention shifts. His findings show that attention shifts gauged from an examination of electoral manifestos, are mainly responsible for the witnessed dramatic expansions or contractions in budgetary items. Moreover, the importance of institutional friction is confirmed; when it proves difficult to change the status quo, the changes in such items tend to be more dramatic. As the theory foresees, left-right ideology has a very limited impact.

Summing up then, the classical party mandate theory and the agenda-setting theory see policy change as resulting from different processes. Party mandate theory submits that changes happen (or should happen) when new governments with different preferences take power. Alternation in government between left and right parties (or coalitions) should correspond to changes in the ways public money is spent. On the other hand, those scholars engaged with the study of attention-based models do not see political ideology as a main explanatory variable. Most of the inputs demanding change are exogenous to the political system, coming from the external environment. Parties are important because they choose which inputs are to be prioritized. Change is slowed down by cognitive and institutional friction, so change is more likely in the case of those policy fields receiving the most attention. The idea that it is necessary to go beyond the simple distinction between left and right parties is also proposed by scholars working in the partisan theory tradition: based on the work of the MRG/CMP/MARPOR group (Klingemann et al., Reference Klingemann, Volkens, Bara, Budge and McDonald2006), several recent studies on public expenditures have related the salience of certain issues in the manifestos of governing parties to policy change (Busemeyer, Reference Busemeyer2007; Wenzelburger, Reference Wenzelburger2015). To put it in other words, the agenda-setting framework is compatible with some recent and refined versions of the partisan theory based on the parties’ capability to prioritize the policy issue, stressing their salience. Both approaches look at some kind of party preferences, though they differ on two important aspects: first, whether preferences are assumed to be ordered on a single left-right continuum or are multidimensional; second, whether preferences are sufficient to trigger policy change or a particular commitment is needed (issue prioritization).

The research design

Having presented the main theoretical arguments at the core of this study, we now present the operational hypotheses and the research design. The paper will analyse public spending changes in Italy during the entire republican period (1948–2009), by looking at four policy areas: defence, public order, welfare, and education. A first hypothesis drawn from the classical partisan theory discussed above, and can be formulated as follows:

HYPOTHESIS 1A Right-wing governments increase spending on defence and public order, while left-wing governments increase spending on welfare and education.

The association between ideology and type of spending is highly intuitive, being linked to the defining differences between left and right as they emerged in the 20th century (Budge, Reference Budge2001).

This hypothesis rests on the assumption that governments can be treated as unitary actors, having some collective preferences over the desired amount of public money to be spent on certain policy areas. However, the influential veto-actor approach to the study of policy making (Tsebelis, Reference Tsebelis1995; Tsebelis, Reference Tsebelis2011) suggests that it is more realistic to consider that governments are composed of different actors with different preferences. When the number and the polarization of veto actors increase, the winset (i.e. the alternatives beating the status quo) shrinks and the possibility of achieving policy change is reduced. This theory has been successfully applied to the study of budgets (Franzese, Reference Franzese2002; Tsebelis and Chang, Reference Tsebelis and Chang2004), proving that countries with many veto players have difficulties altering the budget. If the veto players theory accurately describes how governments behave, the overall (average) ideological position of the government would lose significance. Rather, the possibility to increase or decrease public expenditures would depend on the ideological positions of the two most extreme governing parties, whose distance has a direct impact on the size of the winset. From this argument, the following hypothesis can be drawn:

HYPOTHESIS 1b The effect of government ideology is conditional on cabinet’s ideological range. When the range increases the effect of government ideology decreases.

Finally, the agenda-setting approach does not take into account party positions, only attention. Parties may have different positions, but the frictions hindering policy change can make it difficult for preferences to be translated into policies. Governments are able to prioritize only a few issues at the same time, and only on those issues where they can increase spending.

HYPOTHESIS 2 Spending increases are larger in those policy areas prioritized by governing parties.

The Italian case: an increasingly complex scenario?

Having presented the theoretical framework underlying our study, we can now explain why Italy is an interesting case where testing the above illustrated hypotheses. We believe that studying a relevant case from a diachronic perspective allows us to assess the respective roles of ideology and attention, while controlling for country-specific factors.

Studies devoted to one or two countries have been the norm for studying the outcomes of budgetary policy making, and are still popular because they enable a quantitative approach to be combined with a firm control of country-specific phenomena (Soroka and Lim, Reference Soroka and Lim2003). They can also be used in ‘critical cases’ to criticize an established theory (Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner and Jones2009). However, single-country studies generally suffer from weak statistical analysis due to the limited number of observations, which are often as few as 20 (Budge and Hofferbert, Reference Budge and Hofferbert1990; King et al., Reference King, Laver, Hofferbert, Budge and McDonald1993; Soroka and Lim, Reference Soroka and Lim2003). Thanks to new data on public spending by policy area, provided by national sources and checked for historical consistency, we can rely on powerful statistical analyses (based on four categories of spending observed over a period of more than 60 years,) without sacrificing the substantive control of the case. Moreover, by focussing on one single country, we are better able to identify any role that ideology may play. Obviously cross-country studies represent the best way to test theories, but for the purpose of this study they also present some limitations. First, they assume that the meanings of ‘left’ and ‘right’ are the same the world over, posing a very high obstacle for the traditional partisan theory to overcome. Second, as a result of data availability, they generally focus on a single category of spending (often total expenditure or welfare) and cover limited periods for which comparable data released by international sources are available.

Before introducing the data and methods employed in this study, we shall offer some important background information regarding the Italian case, and explains why it is a good case to analyse. Basically, we argue that in the whole republican period, though for different reasons, governments have never been in a very good position to implement their electoral pledges. Therefore, Italy represents a sort of least likely case for our theory (Eckstein, Reference Eckstein1975): if partisan preferences had an impact in Italy it is likely that they have also an impact in other countries.

For about 45 years of the latter half of the 20th century, Italy was a typical European party government democracy characterized by the predominance of the Christian Democratic party, which in fact governed the country from 1948 to 1992 (as the largest party and, for most of the time, with one of its leaders as Prime Minister). The standard interpretation given to this lengthy period of political stability (despite the presence of rather unstable cabinets), is that of a dominant party surviving without governing (Di Palma, Reference Di Palma1977): the centrality of parliamentary parties and the lack of central control over budgetary politics, resulted in highly pervasive, continuous micro-sectional legislation, often based on agreements stipulated with the left-wing opposition. Even though the enduring prominence of the Christian Democrats means that there were no noticeable differences in the ideological stances of these various governments, their policy pledges considerably differ in the four different periods of coalition governance covering the period 1948–92 (Cotta and Verzichelli, Reference Cotta and Verzichelli2007). Nevertheless, during the so-called First Republic Italian governments did not enjoy considerable agenda powers (Döring, Reference Döring1995; Zucchini, Reference Zucchini2011). This weakness significantly hindered their capacity to implement their programmes.

The period from 1992 onwards (the Second Republic as it is referred to in journalistic jargon), on the other hand, presents a completely different scenario: after transitional governments during the period 1992–94, including two technocratic caretaker cabinets, the partisan composition of governments changed several times, with the alternation of centre-left and centre-right governments up to the recent economic crisis and the consequent formation of a new technocratic government, led by the former European commissioner Mario Monti, in 2011 (Marangoni and Verzichelli, Reference Marangoni and Verzichelli2015). Indeed, the 1994–2009 period saw a total of 10 different cabinets, and a frenetic alternation of centre-right and centre-left majority coalitions representing virtually all parties within parliament. However, the capacity of governments to fulfil their pledges was limited by the difficult status of the country’s public finances, which required a series of reforms to the budgetary institutions. Indeed, when compared with other European democracies, Italy presents a peculiar lateness in developing efficient executive control over the budgetary process (Hallerberg, Reference Hallerberg2004): it was only after the establishment of the Economic and Monetary Union in the late 1980s, that such a capability emerged. Since then, however, the economy has suffered repeated recessions, and policy making in all the important public spending sectors had been increasingly affected by the state of the economy.

From these reasons, the long-term analysis of the Italian case, taking in the First Republic and the two decades following the large-scale changes introduced in the early 1990s, can be seen as a solid area in which to test hypotheses based on the role of policy attention and party ideological preferences, whilst controlling for several unobservable country-specific factors.

Data and operationalization

This section discusses the data and methods used to test the aforementioned hypotheses. The analysis covers the entire republican period in Italy, from 1948 to 2009. We use data provided by Italian Ministry of Economy and Finance (Ragioneria Generale dello Stato, 2011). The data set contains yearly data on public expenditures on eight functional categoriesFootnote 2 that are broadly comparable with the ‘Classification of the functions of government’ (COFOG) system developed in 1999 by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.Footnote 3 These figures concerned total payments recorded in the annual final balance of payments and refer to the General Government. Focussing on General Government (which includes Central Government, Local Government, and Social Security funds) is not an issue because despite the attempts to decentralize political and fiscal powers in the mid-1990s, Italy has remained a persistently centralized country (Baldini and Baldi, Reference Baldini and Baldi2014).

In particular, we look to public expenditures [as a share of gross domestic product (GDP)] on four policy areas:

-

1. Welfare (including Social Security, Healthcare and Housing);Footnote 4

-

2. Education (all levels);

-

3. Public order and justice;

-

4. Defence.

The main independent variables are the attention paid by Government to each of the policy areas, and the Government’s position on the left-right political scale. This paper relies on the expert surveys considered in the ParlGov data set (Döring and Manow, Reference Döring and Manow2012) in order to measure different Governments’ Political Centre of Gravity. The left-right index ranges from 0 (extreme left) to 10 (extreme right). Measuring the political orientation of political actors on a left-right axis is a rather complex task, and scholars have developed several different measures for such purpose. In the expert survey approach, country experts are asked to rate each party’s position on the left-right continuum (Castles and Mair, Reference Castles and Mair1984; Benoit and Laver, Reference Benoit and Laver2006). An alternative approach, based on the work of the MRG/CMP/MARPOR group, is to scale the left-right position of parties by classifying their electoral manifestoes as either left or right by subtracting the left-leaning statements from the right-leaning statements, and dividing this number by the total number of mentions made in the respective manifesto. The resulting measure is known as the Rile scale (Budge, Reference Breunig2001). In this study, we have opted for the expert survey approach, in order to utilize a measure that is computationally unrelated to the measure of attention allocation.

The calculation of the attention paid by governing parties to each policy area is based on the work of the MRG/CMP/MARPOR group (Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Lehmann, Merz, Regel and Werner2014). In order to take account of the fact that the content of Italian party manifestos has changed over time, with increasingly more attention being paid to specific issues rather than to broad ideological statements, our analysis only includes those categories of statement containing direct references to increased spending on certain policies or to increased state involvement in the market. The resulting scale measures the proportion of attention paid to each policy area, to the total of all spending-related references. See Appendix for details.

Both measures (government ideology and attention distribution) are available at the party level, and so they are transposed to cabinet level by weighting each governing party’s position with its share of seats in the lower house. For those years in which there was more than one government, the score of each government is weighted according to the number of days it was in charge.

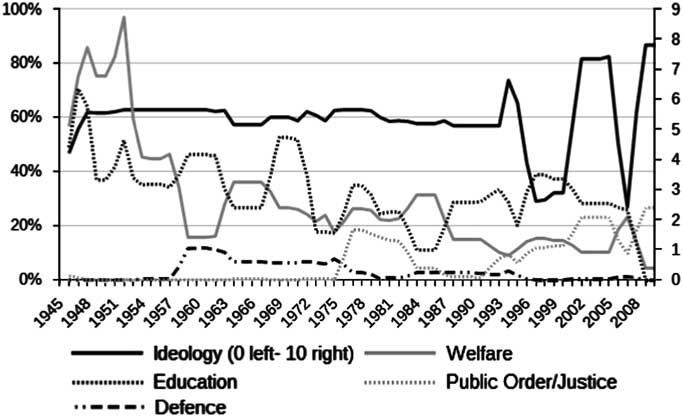

Figure 1 shows the evolution of Italian governments in terms of their political colours and their attention to each of the policy areas in question. As mentioned in the previous section, from the creation of the Italian Republic right up until the 1990s, Italy was ruled exclusively by coalition governments in which the centrist Christian Democratic Party played a pivotal role. However, those governments widely differed in terms of the attention they paid to various issues. Since the early 1990s, the ideology of Italy’s governments has varied considerably.

Figure 1 Government ideology (right axis) and attention to several policy sectors in the electoral manifestos of the governing parties (left axis).

Three main control variables are included in the models. The first is simply the GDP growth rate, designed to take into account governments’ potential to increase spending. A growth in the GDP increases the fiscal capacity of governments, and their spending potential. On the other hand, governments can implement countercyclical policies, by increasing spending on certain categories when the state of the economy deteriorates. For these reasons, it is important to include a measure that takes the economic cycle into account. The second is the degree of centralization in the budgetary process. Several cross-national studies have provided convincing evidence that centralization of the budgetary process limits the tendency of parliament to expand public spending. In republican Italy, the degree of centralization of the budgetary process emerged relatively late, but then wenton to increase considerably, in particular as a reaction to the critical state of the nation’s public finances. Without controlling for the degree of centralization of the budgetary process, one may wrongly attribute the effects of institutional changes to other factors. Cross-country studies often include the ‘average level of fiscal centralization’ in each country, or only consider one particular point in time. A more detailed assessment of the extent to which the Italian budgetary process has evolved from extreme fragmentation to a certain degree of centralization, can be achieved by calculating an index measuring centralization on a yearly basis. This index is based on previous comparative works (Lienert, Reference Lienert2005; Wehner, Reference Wehner2006) assessing the degree of procedural fragmentation of budgetary processes in a multidimensional space. Here, we focus on a detailed grid of indicators concerning the centralization of executive planning and legislative approval, in order to account for each step in the historical evolution of Italy’s budgetary system (see Appendix for details).

The third control variable is the year of election, designed to take into account the electoral political cycle. Existing literature suggests that politicians have reasons to generate fiscal expansion or to distribute specific benefits at election times (Nordhaus, Reference Nordhaus1975). For instance, in a study of 20 OECD countries, Potrafke (Reference Potrafke2009) found considerable evidence of an electoral political cycle in welfare spending. However, some scholars have also put suggested that politicians may alter the composition rather than the total amount of public spending, by earmarking greater resources for more visible programmes. In order to take account of this phenomenon, we have included a dummy variable for each year in which national general elections took place (Table 1).

Table 1 Summary statistics for the dependent and independent variables

GDP=gross domestic product.

a Growth rate, computed as the change in the natural log.

Table 2 Ideology and policy priorities as determinants of public spending

GDP=gross domestic product.

Robust standard errors in parentheses.

+ P<0.10, *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Methods and results

Our immediate expectations are that left-wing governments are more inclined to raise both welfare spending and education spending, while right-wing governments are more inclined to raise defence and public order spending. We would also expect governments whose partisan actors pay more attention to a given problem, to be more likely to increase spending on resolving that problem.

As previously mentioned, we also control for the centralization of the budgetary process, for electoral years and for GDP growth rate. As spending in year, t is mainly decided in year t−1, all independent variables enter the regressions at their lagged levels. The exception is the electoral year, which enters the regressions at the lead level because governments are expected to manipulate spending the year before elections. The basic specification of the full model is as follows:

where ΔlnX t is the growth rateFootnote 5 in annual spending (of the relevant category) at time t, ΔIdeology t−1 the change in the cabinet’s political centre of gravity at time t−1, ΔlnAttention t−1 the growth rate in the emphasis placed on the relevant issue by the governing parties at time t−1, Centralization t−1 the index of budget centralization at time t−1, Election t+1 a dummy with a value of 1 in the years before elections, and with a value of 0 otherwise, while ΔlnGDPgrowth t−1 the growth rate of GDP at time t−1. A second specification of the model includes an interaction between the cabinet’s political centre of gravity and the cabinets’ range of ideological positions. The variable Range t−1 measures the distance between the two most extreme governing parties, and is meant to capture the effect of veto players within the government.

$$\eqalign{ {\rm \Delta }\ln X_{t} {\rm \,{\equals}}\,\alpha {\rm {\plus}}\beta _{{\rm 1}} {\rm \Delta Ideology}_{{t{\minus}{\rm 1}}} {\rm {\plus} }\beta _{{\rm 2}} {\rm Range}_{{t{\minus}{\rm 1}}} {\rm {\plus}}\beta _{{\rm 3}} {\rm (\Delta Ideology}_{{t{\minus}{\rm 1}}} {\times}{\rm Range}_{{t{\minus}{\rm 1}}} {\rm )} \cr {\plus} \beta _{{\rm 4}} {\rm \Delta lnAttention}_{{t{\minus}1}} {\rm {\plus}} \beta _{{\rm 5}} {\rm Centralization}_{{t{\minus}{\rm 1}}} {\rm {\plus}}\beta _{{\rm 6}} {\rm Election}_{{t{\rm {\plus}1}}} \cr{\rm {\plus}}\beta _{{\rm 7}} {\rm \Delta lnGDPgrowth}_{{t{\minus}{\rm 1}}} {\rm {\plus} }u_{t} $$

$$\eqalign{ {\rm \Delta }\ln X_{t} {\rm \,{\equals}}\,\alpha {\rm {\plus}}\beta _{{\rm 1}} {\rm \Delta Ideology}_{{t{\minus}{\rm 1}}} {\rm {\plus} }\beta _{{\rm 2}} {\rm Range}_{{t{\minus}{\rm 1}}} {\rm {\plus}}\beta _{{\rm 3}} {\rm (\Delta Ideology}_{{t{\minus}{\rm 1}}} {\times}{\rm Range}_{{t{\minus}{\rm 1}}} {\rm )} \cr {\plus} \beta _{{\rm 4}} {\rm \Delta lnAttention}_{{t{\minus}1}} {\rm {\plus}} \beta _{{\rm 5}} {\rm Centralization}_{{t{\minus}{\rm 1}}} {\rm {\plus}}\beta _{{\rm 6}} {\rm Election}_{{t{\rm {\plus}1}}} \cr{\rm {\plus}}\beta _{{\rm 7}} {\rm \Delta lnGDPgrowth}_{{t{\minus}{\rm 1}}} {\rm {\plus} }u_{t} $$

The specification of a model with spending growth rate as the dependent variable is useful for two reasons; first, it avoids the problems of spurious, non-sensical regressions that are often seen when time series are non-stationary. Second, we use growth rates to build on the latest budgetary studies, both those in the punctuated equilibrium tradition and those taking the partisan theory line (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Baumgartner, Breunig, Wlezien, Soroka, Foucault, François, Green-Pedersen, Koski, John, Mortensen, Varone and Walgrave2009; Potrafke, Reference Potrafke2009; Efthyvoulou, Reference Efthyvoulou2011).

As Achen (Reference Achen2001) noted, many budgetary studies in political science use spending data in levels, and thus probably contain non-stationary data. The risk of ignoring non-stationarity is considerable, because two non-stationary variables are likely to result as being correlated even if no meaningful relation exists (Granger and Newbold, Reference Granger and Newbold1974). Both the inspection of the correlogram and the Augmented Dickey–Fuller test suggest that all our dependent variables contain a unit root when expressed in absolute terms (share of GDP spent on each function). However, the time series are stationary once transformed into growth rates.Footnote 6 An additional econometric problem in the analysis of time series is deciding whether a dynamic model is needed: we specified an alternative model including one lag of the dependent variable, but in all regressions the coefficient proved to be non-significant. All models exhibit a small degree of heteroscedasticity, so robust standard errors are used (Table 2).

All models include the same independent variables, and only differ in terms of the category of spending and the corresponding measure of attention. The model fitting is moderate for all models with the exception of the public order model, where it is very low. A moderate model fitting is the norm for models using differenced time series, which do not include the lagged level of the dependent variable (Achen, Reference Achen2001).

With regard to the control variables, the models lend some support to the policy cycle hypothesis: there is evidence that governments reduce welfare and education spending the year before elections. While this might seem counterintuitive, this result must be considered together with another finding, namely that elections have a positive, substantially important and statistically significant effect on ‘Economic Affairs’ spending. This broad category includes spending on infrastructures, agriculture, industry, and other sectors of the economy. This suggests that the year before elections, governments prefer to increase spending on visible matters at the expense of long-term programmes. All other control variables fail to have a consistent impact on expenditure growth. Economic growth is related to expansions in Defence spending. Budgetary centralization seems to be more related to increasing public expenditures in the sector of Defence and to contractions in Welfare spending. Such evidence seems to mark a process of executive strengthening: in other words, budget centralization rewards the core executive preferences while it penalizes the demands of parliamentary parties supporting the same government. However, these results fail to reach the conventional level of statistical significance in the second specification of the models.

The first specification of the model compares the impact of government ideology and attention shifts to influence public expenditure. The coefficients of the attention variables are positive and statistically significant for Defence and Welfare spending, while it is indistinguishable from 0 in the models for Public Order and Education. Specifically, the results suggest when Attention to Defence grows by 1% spending on Defence increases by 0.01%. The low value of the unstandardized coefficient of Attention to Defence can be misleading if one does not take into account the distribution of that variable (see Table 1). The series measuring the growth rate in Attention to Defence displays a high degree of variability, as its std. Dev. is over 2. Basically, this means that governments widely differ in their attention to defence, and dramatic increases and reductions in the importance attributed to this topic are quite common. Attention also has a positive, statistically significant effect on welfare spending: a 1% growth of the attention given to Welfare leads to a 0.2% increase in welfare spending. Welfare represents a considerable proportion of public spending, thus the effect that the attention paid to this subject cannot be overlooked. Finally, our models offer no evidence of any relationship between attention and spending levels with regard to Public Order and Education. Thus, the validity of the attention hypothesis is conditional upon the policy sector in question. The coefficients of ideology are always very far from the conventional level of statistical significance. Following King et al. (Reference King, Laver, Hofferbert, Budge and McDonald1993), we also estimated a Partial Adjustment Model in levels, obtaining very similar results (see Appendix). It is also worth noting that in this case, the coefficients for ‘attention to defence’ and ‘attention to welfare’ keep their positive and statistically significant sign. Although the estimation of time series models with non-stationary variables can lead to spurious results, we report the complete specification and the empirical results of those models in the Appendix to ensure comparability with classical studies of the party mandate theory.Footnote 7

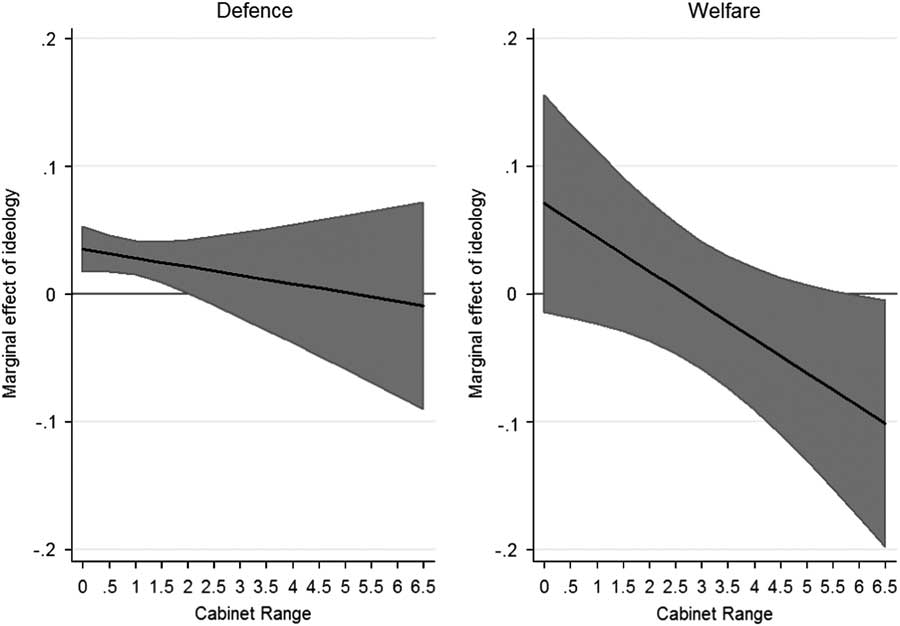

The picture changes slightly in the second specification of the model, where we included an interaction between cabinet’s political centre of gravity and cabinet’s ideological range. In both the regressions on Defence and Welfare expenditures, the coefficient of attention maintains a positive sign, but the first loses statistical significance. By contrast, the combined effect of ideology and range acquires importance, especially in the case of Defence spending. To evaluate the marginal effect of ideology at different levels of cabinet range it is useful to look to Figure 2. Moreover, to help substantive interpretation it is worth noting that, as shown in Table 1, cabinet range has a mean of 1.826 and a std. Dev. of 1.380. The model suggests that an ideological shift from left to right produces a significant increase in defence spending as long as government range is lower than about 2 points. In other words, cabinet ideology has the predicted effect on defence spending only when the preferences of government parties are not too heterogeneous. On the other hand, the effect of ideology on Welfare spending is significant only when government range is greater than about 6, a value that is reached only once in the actual distribution of that variable. For all practical purposes, we can say that according to our model cabinet ideology, measured through the government political centre of gravity, has no effect on welfare spending.

Figure 2 Average marginal effect of Ideology on Defence and Welfare spending at different levels of cabinet range.

Conclusion

In this article, we have analysed Italy’s long-term public spending trend, and have argued that the main assumption of the so-called partisan theory could be revitalized by a broader hypothesis matching the effects of partisan preferences to the logic of attention. As we have explained, the focus on a case study like Italy is especially useful because Italian governments have never been in a good position to convert their pledges into public policies. In the First Republic, governments lacked significant agenda powers, while in the Second Republic they were obliged to contain public expenditures.

The results of our empirical test call for nuanced comments: when considered in isolation, the ideologies of governments, measured in terms of their position on the left-right spectrum, have no impact on spending decisions. However, when we take into account that the ability of governments to change the status quo depends also on the absence of veto players, government ideology proves to be an important factor in determining defence spending. In other words, the simplest version of the partisan theory based on government ideology would not seem to offer a convincing explanation of changes in the composition of public spending. However, our results suggest that cabinet ideology can have some impact when the positions of governing parties are not too polarized. When we move to the hypothesis suggested by the agenda-setting approach, the attention paid to some relevant policy sectors in party manifestos is positively correlated to public spending changes. More specifically, greater attention to defence and welfare issues in a party’s electoral platform emerges as a significant factor in predicting changes in the way public money is spent. This result fits nicely with some of the findings of the agenda-setting approach, whereby expansion in the partisan allocation of attention signals the commitment to increase spending.

In summary, this article suggests that parties still have a role to play, although their importance can be fully appreciated only by combining different approaches. Party differences matter when it comes to spending choices, but in ways that are more complex than both the original partisan theory and the agenda-setting theory foresaw. Elections and changes in the composition of the cabinet can trigger policy change, even in a case where it was unlikely to observe a correlation between party preferences and spending changes.

Two questions remain unanswered, however, and as such they call for further theoretical reflection and empirical research. First, we showed that partisan preferences only seem to work in certain policy areas. Specifically, in the case of Italy there is no sign of any relationship between partisan preferences and two important spending categories, namely Public Order and Education. Obviously, this negative finding might be due to the limited nature of our data: first, the categories are indeed broad, encompassing a number of items;Footnote 8 second, when it comes to partisan attention, the correspondence between issues and spending categories are far from perfect. Moreover, public expenditures are influenced by several factors, many of them beyond government’s control: for this reason other studies in the agenda-setting tradition prefer to relate partisan attention to budget commitments (budget authority) rather than to actual public expenditures (Jones and Baumgartner, Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005b). On the other hand, the divergences between different policy areas may be due to substantial differences in the kind of attention devoted by governing parties to each of these areas. For instance, comparing the United States and the United Kingdom, Soroka and Lim (Reference Soroka and Lim2003) found that only in the United States is there a positive relation between attention and public expenditures on healthcare. To explain this difference, they claim that only American parties clearly focus on spending in their electoral programmes, while British parties make only general statements on the topic. In a nutshell, not only the quantity but also the quality of attention may be relevant.

Finding a relation between some measure of partisan preferences and their actual spending decisions is also important for theoretical reasons. It means that parties still have a role to play, albeit in ways that are more complex than the original partisan theory foresaw. Once again, we reiterate our belief that extensive research – from a truly comparative perspective – is needed in order to explain the robustness of the hypotheses concerning the relevance of partisan preferences across time, countries, and policy sectors. However, the findings that emerge from our detailed study of an increasingly complex story of public spending persuade us of the strength of our argument: the traditional partisan theory and attention-based explanations should be integrated when one looks at the long-term public spending trend; this assertion opens the way to a fascinating series of further hypotheses to be explored in the future.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments, which contributed to improve the quality of the manuscript.

Financial Support

The research received no grants from public, commercial, or non-profit funding agency.

Appendix 1: Measures of attention

For all election programmes (party manifestos) the MRG/CMP/MARPOR group (Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Lehmann, Merz, Regel and Werner2014) reports the percentages of quasi-sentences devoted to 56 categories grouped into seven major policy areas. Our attention measures are computed as the ratio of the percentage of sentences devoted to the category of interest, to the proportion of the manifesto devoted to categories related to spending.

The following are the details of such measures:

Attention to Defence=per104/spending categories

Attention to Public Order=per605/spending categories

Attention to Education=(per502+per503+per506)/spending categories

Attention to Welfare=(per503+per504)/spending categories

where

and all the other variables are defined according to the labels contained in the MRG/CMP/MARPOR codebook.

Table A1 Items for the index of budgetary centralization

Appendix 2: The index of budgetary centralization

The control variable index of budgetary centralization, in keeping with several previous studies of budget institutions, combines two indexes of executive power entitled index of executive planning and index of legislative approval. The sum of the two indexes provides a rough, albeit consistent, overall measure of the centralization of the process. The components and relative weights of both indexes are as follows.

Table A2 Ideology and policy priorities as determinants of public spending

Appendix 3: A Partial Adjustment Model

The specification of the full model is as follows:

The dependent variable and the GDP are measured in inflation-adjusted millions of euro (2009).

The dependent variables are non-stationary, thus the results might be spurious. They are reported for comparability with older studies.