Introduction

Twenty-five years after its enactment, Italian Law no. 81 of 1993 governing the direct election of the mayors continues to be commonly considered one of the main (if not the only) successful institutional innovations appreciated by citizens (Baldini and Legnante, Reference Baldini and Legnante2000: 38; Piselli and Ramella, Reference Piselli, Ramella, Catanzaro, Piselli, Ramella and Trigilia2002: 11; Di Virgilio, Reference Di Virgilio, Caciagli and Di Virgilio2005: 5). In this paper, our aim is to explore one of its most important aspects: the personalization of the vote. By studying an original dataset that includes information on all mayoral candidates in Italian municipalities between 1993 and 2017, we will seek to trace a sociodemographic and political profile of the most personalized candidates: that is, those candidates who succeeded in attracting many more votes than those cast for the lists supporting them. In fact, the attractiveness of mayoral candidates compared with their lists has been interpreted as a form of personalization of politics (Legnante, Reference Legnante1999; Baldini and Legnante, Reference Baldini and Legnante2000), albeit an imperfect and partial one (Pasquino, Reference Pasquino2001: 97). The electoral system that applies to municipalities with over 15,000 inhabitants, which was introduced in 1993, is part of the family of mixed-member electoral systems and provides for a dual contest: a majoritarian one in the case of the mayor, and proportional voting (with a majority bonus) in the contest among the various lists. This institutional architecture enables the electorate to vote a split ticket between lists and mayoral candidates, which in turn may lead to a ‘candidate vote gap’ (Plescia, Reference Plescia2016: 9).

In the next section, following a review of the origins of the electoral reform, we will identify some of the objectives that the promoters of the reform were seeking to attain. One relates to ‘personalization’, meaning the enhancement of the individual both within an electoral context and in governmental roles. ‘The personalization of politics and Law no. 81/93’ section offers some thoughts on those aspects of electoral reform that impact on the personalization of politics. Here, we draw a distinction between personalization ‘from above’, which relates to the local political class and the trajectories of a political career, and personalization ‘from below’, which relates to voting orientations and behaviour. In the section ‘The personalization of voting in municipal elections’, we present the results of an analysis focusing on the differences in the numbers of votes cast in favour of mayoral candidates and those cast for the lists supporting them. Finally, based on this empirical evidence, our concluding section offers some reflections on the longstanding nature of the political and voting behaviour of Italians, which help explain certain aspects of the country's current political phase.

Origins, objectives and characteristics of Law 81/1993

The introduction of a new local electoral system in March 1993 was not an isolated event in Italian political history; rather, it was one strand of a broader response that the political class of the time was called upon to provide to the deep crisis affecting Italy at the beginning of the 1990s. The crisis in the Italian political system was caused by various international and domestic factors, and led to profound changes in the political and institutional structure of the country.Footnote 1 Between 1992 and 1994, the party system underwent a radical transformation that signalled the end of the ‘old parties' and the establishment of new political formations. The political class went through a profound transformation, too, with an extremely rapid turnover of parliamentarians (Verzichelli, Reference Verzichelli1996). The same fate befell the electoral rules at all four governmental levels (municipalities, provinces, regions and the two chambers of parliament), all of which were reformed within the space of a few years.

Of these ‘bundles of reforms’ (Bedock, Reference Bedock2017), the most important was unquestionably the reform of the system for election to the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate, which was also introduced in 1993. In his typology of electoral reforms, Renwick (Reference Renwick2010: 16) placed this reform in the category of ‘elite–mass interaction’. Unlike ‘elite majority impositions’, such as the 2005 electoral reform of the Chamber and Senate (see also Baldini Reference Baldini2011: 652), this kind of institutional innovation takes place when the majority of politicians partially lose control of reform procedures and other actors gain ground in the decision-making process.Footnote 2 It can be asserted without too much uncertainty that the electoral reform for municipalities can also be placed in the same category of elite–mass interaction. Both reforms, in fact, were introduced after a referendum campaign promoted by sections of the political class and of civil society, and they were strongly supported by voters at the ballot box (Newell and Bull, Reference Newell and Bull1993). Moreover, in line with a trend affecting many Western democracies (Shugart and Wattemberg, Reference Shugart, Wattemberg, Shugart and Wattemberg2001: 9), the political class of the time decided to give both electoral systems the features of mixed-member electoral systems.

In order to understand the characteristics of the municipal electoral system, account must be taken of the fact that the introduction of the new electoral law arose out of the interests of various actors with diverse decision-making powers. In general terms, we can divide these actors into parties and individual politicians. The former may be motivated, inter alia, by the search for votes, institutional positions and political influence, while the latter may be driven by the desire to be re-elected, or to increase their power within the party or their influence in the broader political context (Renwick, Reference Renwick2010: 30). Aside from personal interest, however, the values of the actors – politicians and non-politicians alike – who had the power to make decisions, also contributed towards shaping the electoral reforms. In this regard, Renwick has identified a number of broad categories that incorporate diverse values. The first of these is associated with democracy, and therefore with a fair distribution of seats and powers, guaranteeing an actual voting choice for voters and increasing the accountability of government bodies and individual politicians. The second category of values relates to the continuation of political and government stability. The third recalls the importance of high-quality governance that manifests itself in an efficient decision-making process and the avoidance of corruption and money-based politics. Other values that might motivate the introduction of new electoral rules are the improvement of policy outcomes and administrative simplicity (Renwick, Reference Renwick2010: 39).

A careful investigation of the origins and features of the 1993 municipal electoral reform makes it possible to identify with some ease both the interests of the main actors involved in the decision-making process, and some of the values that shaped the new system. Owing in part to the inevitable mediation among various actors, in this case between ‘presidentialists’ and ‘proportionalists’ (Baldini, Reference Baldini2002: 378), these interests and values should have been achieved through the accomplishment of certain medium-term objectives. The first, and most important, of these concerned the process of re-legitimization of the main traditional political actors, which had been substantially affected by the corruption scandals. As Renwick claims on this subject, ‘growth of popular alienation from politics and politicians might prompt some in the political class to consider serious electoral reform as a means towards restoring their legitimacy’ (Reference Renwick2010: 12). At the same time, the traditional political actors had every interest in limiting the advance of new political forces, such as the Lega Nord, or extremist forces like the Movimento Sociale Italiano, which had hitherto been ostracized by all the other political groups. The spirit of the time, characterized by powerful anti-political sentiment and hostility towards parties and professional politicians (Bardi, Reference Bardi1996; Morlino and Tarchi, Reference Morlino and Tarchi1996; Sani and Segatti, Reference Sani, Segatti, Diamandouros and Gunther2001; Segatti, Reference Segatti, Torcal and Montero2006; Mete, Reference Mete2010; Mastropaolo, Reference Mastropaolo2012), also suggested that an electoral system should be devised that would enable the parties to take a step back from the political scene and leave more room for individual personalities, possibly from civil society. As Annick Magnier has written in this regard:

At the beginning of the 1990s, the reform of the position of the mayor in Italy was regarded as a form of shock therapy, which would allow new individuals to lead the municipalities and introduce a ‘modern’ anti-party style of making decisions in the public sphere. Municipalities were considered a laboratory for the modernization of the whole political and administrative system, heavily paralysed by the influence of the political parties and the ‘proportional’ principle of decision-making (Magnier, Reference Magnier2004: 167).

A further objective of the electoral reform was to increase the independence of local government with respect to regional and national parties and politicians. This trend was in line with the stratarchical form taken by parties, as suggested at the time by Katz and Mair (Reference Katz and Mair1995: 21). This should also have served to placate widespread hostility towards political parties. It is no coincidence that an extremely popular slogan of the time was ‘localism against the partitocracy’ (Cartocci, Reference Cartocci1991; Segatori, Reference Segatori2003: 119). The stability of local government and councils, which hitherto had been a highly critical element (Cazzola, Reference Cazzola1991: 89), was another objective pursued by the new electoral law. Finally, the increased efficiency and efficacy of the policies established by local administrations must also be included among the main objectives (Piselli and Ramella, Reference Piselli, Ramella, Catanzaro, Piselli, Ramella and Trigilia2002: 23).

What features did the electoral reform need to have in order to attain, or at least to pursue, these objectives? The direct election of mayors, which is unquestionably the most important and innovative aspect of the electoral reform, was designed to increase the independence of local government from party power, to guarantee the continuity of administrative actions, and to improve accountability.Footnote 3 In order to achieve these objectives, the reform provided that the fate of councils should be tied to that of mayors, so that if a council passed a vote of no confidence in the mayor, the council members also had to resign. The new electoral law gave mayors the power to appoint (and dismiss) the municipal executive (giunta). This was intended to enable the attainment of the objective of having parties take a step back, while also improving the consistency and efficacy of public policies. Moreover, the provision of a run-off in municipalities with over 15,000 inhabitants can be seen as a useful means with which to isolate emerging political forces as well as traditional, but more extremist, parties, both of which are difficult to form coalitions with. Finally, the provision of a split vote should have given greater freedom to voters by freeing them from what the parties were offering electorally. The law provided that in larger municipalities voters could have one vote for a list, and another vote for a mayoral candidate who was not necessarily associated with that chosen list. This meant that voters could, if they wished, emancipate themselves from candidates and parties and reward the individual characteristics of a mayoral candidate. In other words, as a result of both the direct election of mayors and the separate vote, the reform in municipalities boosted the personalization of politics, which was also seen as an appropriate antidote to rapidly spreading anti-political and anti-party feelings (Legnante, Reference Legnante1999: 395). This was a completely new aspect of the Italian political system which, due to its historical legacy, had always treated such a development with suspicion. Following a trend seen in many Western democracies (Renwick and Pilet, Reference Renwick and Pilet2016), the municipal electoral system accentuated the personalization of politics and opened the way to the electoral reform of the Chamber of Deputies and Senate, which provided for 75% of the seats being attributed as a result of first-past-the-post majority contests, and which would be approved some months later. Both prepared the ground for the entry of Silvio Berlusconi, who would make the personalization of politics his essential feature, forcing all the other players in the Italian political system, parties and politicians alike, to make rapid adjustments accordingly. Following the long period of partitocracy, this marked the beginning of the ‘leaderocracy’ phase (Cotta, Reference Cotta, Jones and Pasquino2015: 50), for which local government became the initial laboratory and testing ground as of 1993.

The personalization of politics and Law no. 81/93

While the opinions of scholars and commentators on the origins and characteristics of the political crisis of the early 1990s vary considerably, there is general agreement that the crisis led to a marked acceleration of the personalization of politics. In general terms, the phenomenon can be defined as the process by which ‘individual political actors become more prominent at the expense of parties and collective identities’ (Karvonen, Reference Karvonen2010: 4), and as Luciano Cavalli noted with regards to the Italian case as early as the first half of the 1990s, ‘it is developing across various dimensions – political, institutional and – perhaps most of all – psychological’ (Reference Cavalli1994: 103). In addition to having a number of different dimensions that are undoubtedly interlinked, the personalization of politics manifests itself in various spheres, which are where it is simpler to identify and observe empirically. Guido Legnante has convincingly identified five of them: (1) the personalization of institutional roles, or presidentialization; (2) the personalization of roles at the top of parties, or leaderization; (3) the personalization of political and institutional communications; (4) the specific personalization of political marketing, in the sense of the broadest sphere of political communications pertaining to electoral campaigns; and (5) the personalization of voting (Reference Legnante1999: 306–307).

Having broadly described the various aspects of the complex phenomenon of personalization, solely for the specific information requirements of this paper, we will now consider how Law 81/93 reinforced this trend, and which of its specific aspects contributed to fuelling it. In order to simplify matters, it is helpful to distinguish between a personalization of politics that relates to the members of the political class, which we might call ‘personalization from above’, and a kind that is inherent in voters, and especially in their voting behaviour, which we might label ‘personalization from below’. In the former case, which relates to the personalization of political supply, ‘politicians are turned into entrepreneurs of themselves by their candidacy at elections, they win as individuals, and they manage their conduct as a “representative” independently: their main point of reference is not their party, but the electorate’ (Cavalli, Reference Cavalli1994: 103). An analysis of this aspect means examining political careers, candidacies, political communications, and specifically analysing candidacies that have been rewarded by positive electoral results. In the latter case, on the other hand, which focuses on political demand, ‘voters make personal voting choices, move away from being conditioned by groups, vote on the basis of their personal trust in the candidate, and then seek to maintain a direct relationship with the elected representatives’ (Cavalli, Reference Cavalli1994). As far as this second aspect is concerned, the analysis focusing on the split ticket that the new electoral system has made possible is undoubtedly extremely significant.

The rules introduced by the new electoral system for municipalities and provinces, made it possible for the personalization of politics from above to be increased and encouraged, primarily because they gave mayors a more central role to play. Following the reform, the nature and balance of the dual zero-sum game involving mayors changed: on the one hand, mayors were in contrast with the town council and its members, and on the other, they now had to deal with the party (and/or the coalition) of which they were a part, dialectically and from a position of strength. As scholars and commentators from a number of different areas of specialization have clearly shown, it is mayors who have grown in strength in this new political and institutional dynamic, while for various reasons, parties and local assemblies have been weakened. Post-reform mayors draw their strength from having been directly chosen by voters, while party-based mediation is declining. Above all, the introduction of the simul stabunt simul cadent principle by which a vote of no confidence in the mayor automatically leads to the dissolution of the council, reduces parties’ and councillors’ room for manoeuvre.

Although the new electoral system did not modify the formal powers and prerogatives of mayors, it assigned them great importance and political centrality. The ‘new mayors’ therefore became political personalities who in many cases emerged from the local political scene and stepped into the national political debate. From this standpoint, the increased importance of mayors has led to a change in the overall nature of political representation, not only at a local level (Bettin Lattes and Magnier, Reference Bettin Lattes and Magnier1995; Dato Giurickovic, Reference Dato Giurickovic1996; Catanzaro et al., Reference Catanzaro, Piselli, Ramella and Trigilia2002; Segatori, Reference Segatori2003), as might be thought, but also nationally (Lo Russo and Verzichelli, Reference Lo Russo, Verzichelli, Edinger and Jahr2015: 38), with the affirmation of a phenomenon that Aldo Di Virgilio described as the ‘localisation of the parliamentary political class’ as early as 1994 (Reference Di Virgilio1994, 111). Law 81/93 therefore had the effect of seeing more (former) mayors elected to Parliament. At the same time, however, as typically happens in political systems with multiple government levels (Stolz, Reference Stolz2003; Borchert, Reference Borchert2011; Borchert and Stolz, Reference Borchert and Stolz2011; Dodeigne et al., Reference Dodeigne, Krukowska, Lazauskiene, Heinelte, Magnier, Cabria and Reynaert2018), and as was already clear immediately after the introduction of Law 81/93 (Vassallo, Reference Vassallo and Barbera1994: 40), the increased political weight associated with the role of the mayor has also had an impact on the preferences and career ambitions of political actors, and has made a mayoral position appealing even to prominent politicians at the parliamentary, or even ministerial, level. In fact, as a number of studies have shown (Verzichelli, Reference Verzichelli2010: 95; Lo Russo and Verzichelli, Reference Lo Russo, Verzichelli, Edinger and Jahr2015: 50), it is not unusual to find politicians with a solid national–political profile, choosing to ‘return’ to local government, thereby favouring a ‘centrifugal’ rather than a ‘centripetal’ trajectory, especially in large and medium-sized cities. New mayors who follow the traditional political path have found that their careers have been made easier because of their experience in the office of mayor, which due to its central importance since 1993 has enabled them to advance their careers at a pace that once would have been more difficult.

As we have indicated, Law 81/93 has also enabled personalization ‘from below’ to manifest itself fully. The electoral system for municipalities with over 15,000 inhabitants may, in fact, be viewed as a mixed electoral system that enables a horizontal-type split ticket to be used.Footnote 4 With regards to the analyses offered by the literature on this type of split ticket (Shugart and Wattenberg, Reference Shugart and Wattenberg2001; Chiaramonte, Reference Chiaramonte2009), the electoral system implemented in larger municipalities does not limit the voter's choice to that between mayoral candidates on the one hand and the electoral lists (whether civic or party-based) on the other. One very significant figure to be taken into consideration in order to understand how voters vote, is the candidate for the position of councillor, for whom a personal preference can be expressed. From this standpoint, therefore, unlike most of the analyses on split tickets, the gap between voting for lists and voting for mayoral candidates must be interpreted in light of this dual incentive to vote for lists: programmatic and ideological as regards a vote for a party, and personalistic and particularistic as far as voting for a council candidate is concerned. However, the electoral rules do not make it possible to vote for a council candidate and for a list other than the one comprising said council candidate.

In conclusion, the introduction of direct election of mayors has undoubtedly facilitated and channelled the personalization of politics, both ‘from above’ and ‘from below’. More particularly, with regards to the five areas of personalization identified by Legnante, it can be said that Law 81/93 has had an impact on presidentialization, the personalization of political communications and marketing, and voting personalization. From the perspective of scholars of political and social phenomena, the introduction of this law is of extraordinary interest because, as Legnante has noted, thanks to this law it is possible to actually ‘see’ the personalization of politics and even to ‘measure’ it, albeit only in some of its more circumscribed manifestations. This is what we shall try to do in the next section, as we explore what happened in electoral contests in larger municipalities during the period between 1993 and 2017. The following empirical analysis aims, first and foremost, to describe the most personalized categories of candidate: women or men; losers or winners; left-wing, right-wing or candidates for civic lists; incumbents or challengers; those supported by very few lists, or those supported by many lists; and so on. This initial description becomes more interesting when combined with a number of traditional variables used in electoral studies, such as the geopolitical areas that Italy is usually divided into, and the various phases of application of Italian Law 81/93. This analytical strategy offers a clearer understanding of which factors, taken together, are associated with the most personalized mayoral candidates.

The personalization of voting in municipal elections

Measuring the personalization of voting

With regards to municipalities with more than 15,000 inhabitants, the electoral system introduced by Law 81/93 provides that mayoral candidates must be formally supported by one or more lists, each of which must consist of a number equal to or lower than the number of council posts. Voters may cast two votes, one for the mayoral candidate and the other for the lists and, possibly, for a council candidate. The candidate who obtains an absolute majority of valid votes in the first round is elected as mayor. If no candidate obtains an absolute majority, a second round is held 2 weeks later between the two candidates with the most votes. Each list is attributed a certain number of councillors based on the percentage of votes obtained. The council candidates from each list who obtain the most individual preferences are elected. In order to ensure greater political stability, the lists that support the mayoral candidate are given a majority bonus.

Within the framework of rules that we have briefly described here, voters can use a variety of different voting strategies. If we ignore votes that are not cast (abstentions, blank ballots and spoiled ballots) and focus on the first round alone, we see that voters can choose to cast three types of vote: (1) a ‘personalized vote’, which consists of voting for a mayoral candidate only and not expressing any preference for either a list or a council candidate; (2) a ‘straight vote’, which occurs when a mayoral candidate and a list associated with him or her are voted for (with or without a preferential vote for the council candidate who is on the chosen list); and (3) a ‘split vote’, which is cast when the voter chooses a mayoral candidate and a list not associated with said candidate (here, too, it is possible to indicate, or not indicate, a council candidate from the chosen list) (Legnante, Reference Legnante1999: 445). Since they can cast a split vote, voters are therefore free to reward particularly appealing mayoral candidates and to penalize mayoral candidates that they do not like (by not voting for them).

Accordingly, while many voters opt for a split and/or personalized vote, a number of mayoral candidates may obtain many more votes than the total of all votes cast for the list supporting them, or conversely they may obtain many fewer such votes. The gap between votes for lists and for a mayoral candidate therefore provide us with useful information about the appeal (or lack of appeal) of each mayoral candidate. This indicator, which is obtained by dividing the votes for the candidate by the votes for the list and adding one,Footnote 5 can be used as a measure of the personalization of votes in terms of both personalization from below (a propensity among voters to make personalized voting choices) and from above (the appeal of the mayoral candidates based on their personal image). If we look at this same phenomenon from a different perspective, we see that a voting gap in favour of the mayor can also be viewed as a weakness of the list of candidates for the council. In general terms, by referring to the three-way division used by Stefano Bartolini and Roberto D'Alimonte to analyse the performances of candidates in single-member constituencies in the first quasi-majority elections in 1994, we can identify three types of candidate: ‘a “good candidate” is one who succeeds in mobilising all the votes in his or her camp without losing any shares along the way. An “excellent candidate” is one who in addition to mobilising his or her reference voters is able to attract votes that would otherwise go elsewhere. A “candidate lacking qualities” is one who not only does not obtain votes from outside but does not even secure all the votes within his or her electoral block’ (Reference Bartolini, D'Alimonte, Bartolini and D'Alimonte1995: 357–358).

Data and methods

Our dataset was developed by consulting (and instituting a dialogue between) the Archivio Storico delle Elezioni (https://elezionistorico.interno.gov.it/) and the Anagrafe degli Amministratori Locali e Regionali (https://dait.interno.gov.it/elezioni/anagrafe-amministratori), for both of which the Ministry of the Interior is responsible. In this way, we obtained a dataset that has the individual candidacy for mayor as its unit of analysis. The dataset covers the period between 1993 and 2017, and includes elections for all Italian municipalities (with a few partial exceptions relating to Valle D'Aosta and Trentino-Alto Adige due to gaps in Ministry sources). Following some initial necessary, laborious ‘cleansing’ operations, the archives ‘settled’ on 108,448 cases relating to 7745 municipalities. The cases relating to the so-called ‘larger’ (superiori) municipalities – that is, those with more than 15,000 inhabitants (10,000 in Sicily and 5000 in Friuli-Venezia Giulia) – where a two-round electoral system applies, numbered 19,223. The number of municipalities considered in the analysis was 825, and the total number of elections was 3649.

With regards to candidates' political colours, we decided to classify them into nine categories. Given the very large variety of situations, assigning each candidate to a category was no easy matter. The preliminary procedure we believed was acceptable and made sense consisted in assigning a position of ‘left’, ‘centre-left’, ‘centre’, ‘centre-right’, ‘right’, ‘Lega Nord’, ‘M5S’, and ‘other’ to the lists in the dataset. This means, for example, that Rifondazione Comunista was labelled as ‘left’ and Forza Italia as ‘centre-right’, etc. Based on this initial classification, the new categories that were later used in the analysis were constructed by taking account of the list, or more frequently all of the lists, supporting a mayoral candidate. It should be noted that one party may support candidates from coalitions with different political colours: for example, if the Democratici di Sinistra (Left Democrats) Party is allied with Rifondazione Comunista (Refounded Communists), the coalition will be classified as ‘left’, while if it is allied with the Margherita (The Daisy Coalition), the coalition will be considered ‘centre-left’.

As the literature on split tickets reveals (Plescia, Reference Plescia2016: Ch. 3), the ecological methods used to study the phenomenon suffer from a fallacy that restricts their informative capacity. Unlike techniques based on survey data, which are nonetheless subject to other methodological problems, ecological analyses do not enable the degree to which split tickets are actually used by the electorate to be measured, because they do not account for the complexity of the flows among the parties and candidates, or the reciprocal set-offs these dynamics produce. At a municipal level, therefore, ecological techniques can only produce an estimate of the minimum number of personalized votes. In our case, the problem of the ecological fallacy does not exist because our objective was not to measure the dimensions of the split ticket at a municipal level, but rather to explore the features of the most attractive candidates. The unit of analysis is therefore the mayoral candidate and not the municipal electoral contest.

Given the characteristics of our archive and the nature of the personalization index, it was deemed appropriate to explore certain dimensions that the socio-political literature has traditionally considered in the study of the political class or the municipal political elite (Melis and Martinotti Reference Melis and Martinotti1988a, Reference Melis and Martinotti1988b; Cazzola, Reference Cazzola1991; Barberis Reference Barberis1993; Montesanti, Reference Montesanti2007). These dimensions comprise the gender of candidates, their age at the time of the election, the political colour of the party or coalition to which they belonged, their level of education, and the area in which they lived. Besides these ‘traditional variables’, we also considered the incumbent effect, the outcome of the election (if the candidate was elected or not elected), and the number of lists supporting the mayoral candidate.

The technique of analysis that we considered most suitable for achieving these objectives was the comparison of the levels of personalization of categories of mayoral candidates that we considered to be outsiders, such as women, the losing candidates, and those supported by a single list. In light of the literature on the political and social differences among the various areas of Italy, and that concerning the phases of application of Law 81/93, we considered in the analysis, where appropriate, both the geographical macro-area and the year of election.

In addition to the analysis, we have also conducted a linear regression, the dependent variable of which is the level of personalization, while the independent variables are: gender, age at the time of the election, education, election outcome (winner or loser), whether the candidate was incumbent or not, number of linked lists, the political position of the coalition supporting the candidate, the period, and the territorial area.Footnote 6 These variables were used to produce three different models: the first model includes the socio-demographic variables (gender, age at the time of the election, education) together with the election outcome; the second model includes, in addition to the aforesaid variables, a number of political variables (incumbent, number of linked lists, political position of the coalition); the third model introduces a further two variables of a more structural, contextual nature (the period and the local area).

The socio-demographic characteristics

Having clarified how, and to what degree, it is possible to measure the personalization of votes in electoral contests in larger municipalities, and the characteristics of the dataset used in the analysis, we can now create a profile of good-quality candidates. The first issue is the gender dimension.Footnote 7 Overall, male and female candidates display rather similar personalization rates. The personalization index for women is 0.12, while in the case of men it is 0.11. If we seek to make distinctions by age, and attempt for example to understand whether young women are more personalized than young men, no significant differences emerge. The territorial dimension, on the other hand, seems to discriminate more (see Figure 1). Contrary to what might be expected, the most personalized candidates are women who run for office in the South and Centre of Italy, with a personalization index of 0.17.

Figure 1. Personalization indexed by gender and geopolitical area (N = 19,219).

It would seem, therefore, that it is in the most developed and modern areas of the country – that is, the Centre-North – that female candidates do not succeed in attracting more personalized votes than male candidates. On the contrary, perhaps it is precisely because the presence of a female candidate for an important high office in the local context stands out more where the social and political role of women still has some way to go towards parity that they are rewarded by voters. Alongside this more ‘optimistic’ interpretation, however, another may be offered that relates to the relationship between mayoral candidates and the lists associated with them. The case can plausibly be made that as a more politically marginalized category, above all in geographical areas where politics are even more of a male preserve, women largely fail to obtain the support of strong council candidates who have the ability to achieve a broad personal consensus that translates into ‘straight’ votes. Accordingly, in the Centre and the South, female candidates are more personalized, partly as a reflection of the weakness of the lists that support them, and partly because in a political structure that remains more male-dominated than is the case elsewhere, being a woman is interpreted as a feature of being an outsider which, as we shall see in more detail below, seems to be customarily associated with a higher level of personalization.

In addition to gender, candidates' age is another important underlying sociodemographic variable that needs to be taken into consideration. In this regard, there does not seem to be an age range that is especially associated with high personalization.

The third and final sociodemographic aspect that the available data have enabled us to investigate is educational level. No especially noteworthy differences have emerged from this point of view. The least personalized category of candidates, who have a value of 0.07 and number only 90 (out of the 12,986 considered), are those with only an elementary school education (to the age of 10 or 11). Candidates who finished middle school (0.11), those with a high-school diploma (0.09), and university graduates (0.10), all display a higher value, albeit only slightly higher.

Political features

In addition to the sociodemographic characteristics, the information that we collected also enabled us to identify the political features associated with candidates able to attract more votes than the lists supporting them. Here, as we shall see, our analysis reveals a number of surprises compared with what might have been expected. To begin with, the most interesting and significant aspect is the correlation between the percentage of votes gathered by the mayoral candidates in the first round and their index of personalization: −117 (N = 19,219). We therefore see a slight, but significant, negative relationship. This can usually be explained either by the greater appeal of the losing candidates, or by the strength of the lists supporting the winning candidates. On average, the personalization level of all winning candidates was 0.07, while the same index for losing candidates rises to 0.12. Paradoxically, the loser was a ‘better’ candidate in terms of his/her appeal, than the winner was. In order to win, therefore, the candidates' individual characteristics undoubtedly count, but it may be even more important to have good lists that can guarantee a large number of votes that will benefit mayoral candidates who are not significantly personalized but who have a close association with the lists backing them. Obviously, lists and candidates are not unconnected, and one of the qualities that is undoubtedly required to be a successful mayoral candidate is the ability to formulate lists of council candidates.

If analysis is conducted from a temporal standpoint (Figure 2) according to geopolitical area (Figure 3), the results just presented are further reinforced, and offer even more interesting insights. In the initial stage of application of the law – until the 1999 general election to be precise – the most highly personalized candidates were the ones who were elected. Starting in 2000, probably because the novelty of directly-elected mayors had worn, and also because the parties had learned the rules of the game better, the level of personalization diminished. Conversely, there was an increase in the personalization of losing candidates, who probably continued to be seen as new, challenging, innovative individuals who were able to contest the new municipal political power of mayors once again rooted in the local political context. The degree of personalization of both categories of elected and unelected candidates alike diminished in 2013 and fell dramatically the year after. One explanation for the sudden decline in 2014 could be the specific type of municipality in which there was a vote in this round, and where there had already been a decline 5 years previously. In addition, the reduction in personalization rates could be a result of the fact that the European election campaign, which is given greater prominence by the parties than local elections and is associated with more general topics in the media, was under way at the same time. The electoral system for European elections, which is proportional and involves macro-regional constituencies, leads parties to present themselves for the election with their own symbols, which gives them greater public visibility. Above all, it is likely that the explanation for this lower level of personalized voting lies in the possibility of casting two preferential votes in council elections instead of only one, as had previously been the case, which was introduced for the first time in 2013. The legislative amendment stated that two votes could be cast provided that the candidates voted for were of different genders. Its primary intention was therefore to balance the gender composition of municipal councils, an objective that was at least partly attained (Agostinelli, Reference Agostinelli2013; Papetti, Reference Papetti2015). It may therefore be that as a result of the thematization underlined by the positive feedback from the dual preference in terms of reducing the gender gap, voters decided to cast a vote for the council, and not for the mayor alone, more often than they had done before, thereby reducing the percentage of personalized votes.

Figure 2. Personalization index of individuals who were elected and not elected over time (N = 19,219).

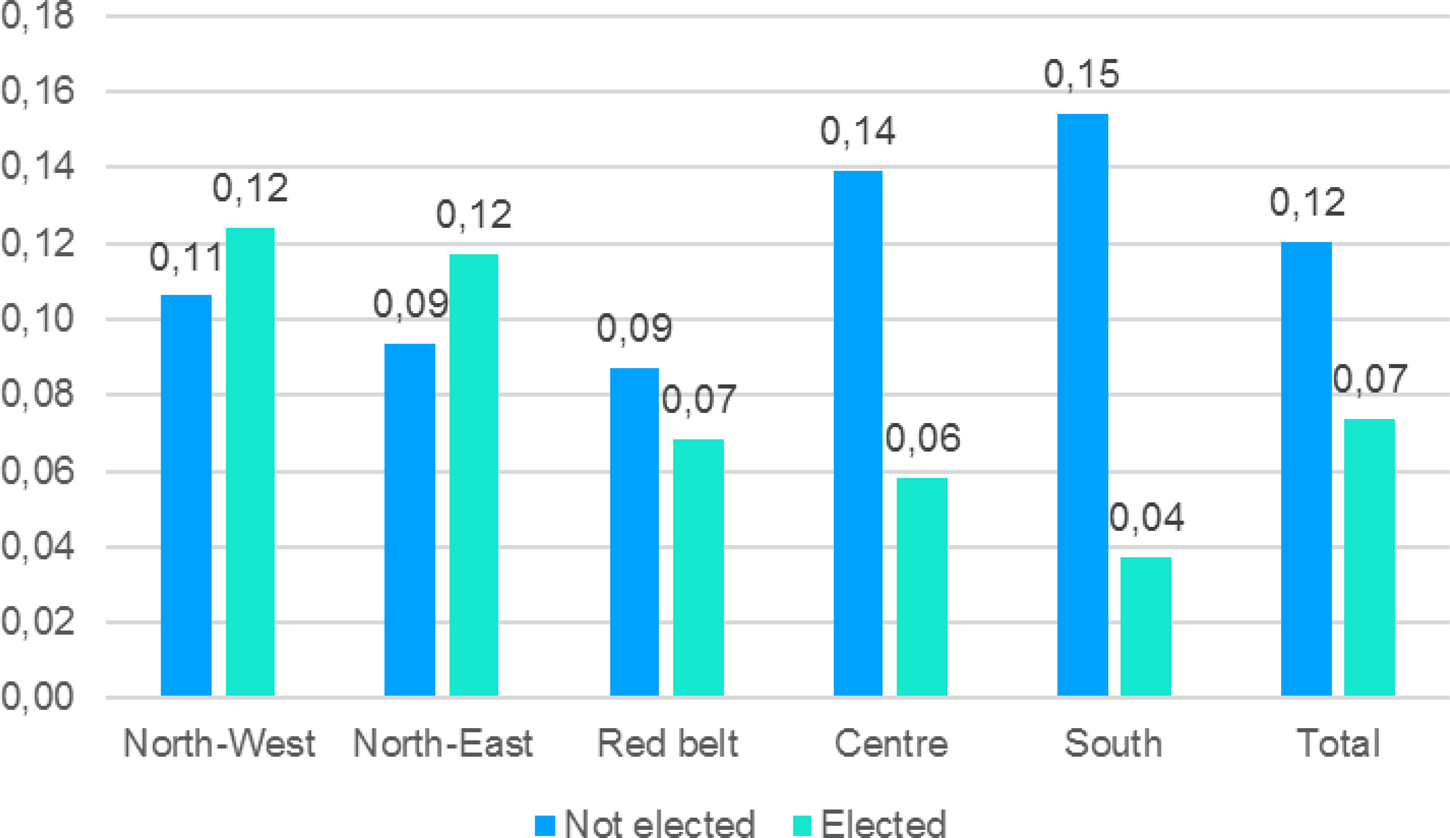

Figure 3. Personalization index of individuals who were elected and not elected by geopolitical area (N = 19,219).

If we divide the levels of personalization of elected and non-elected individuals by area (see Figure 3), we see how diverse local politics still are in the various areas of the country. The most marked differences between the personal appeal of winners and losers are to be found in the South, where non-elected candidates exceed those who were elected by 12 percentage points in terms of personalization, compared with an overall average of 5 points. In the North-East and North-West, on the other hand, it is the winning candidates who are personally more appealing – by approximately two percentage points – than the losers. In the South, therefore, winning candidates rely on very strong lists of council candidates, while unsuccessful candidates have to use their own personal appeal to compensate for weakness in the lists supporting them.

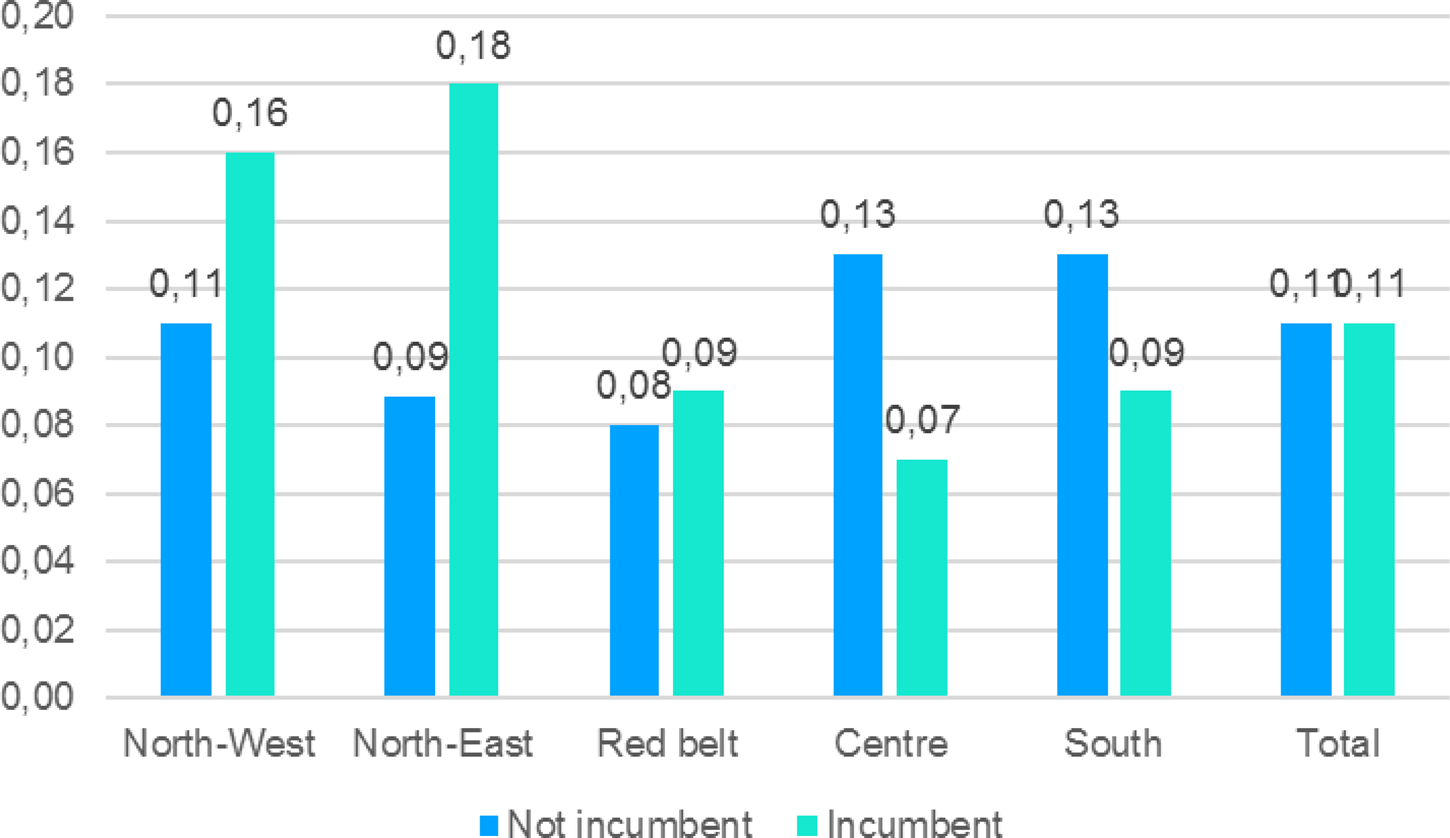

As said, Law 81/93 introduced a limit of two consecutive mandates for mayors. At the same time, direct election provided mayors in office with extensive centrality in the social and political life of their communities. This meant that if the incumbent mayor stood again at the conclusion of the first term, he or she enjoyed considerable visibility, which in turn ensured a high likelihood of re-election. In times of widespread political disaffection, however, this visibility may also count against the incumbent mayor, and even if he or she is the victorious candidate, it may reward the challengers to a greater degree. Overall, our analysis shows that incumbent mayors have the same attractive capacity as their opponents (0.11). Also in this case, disaggregation by territorial area provides information that helps us to understand the phenomenon better. As can be seen (Figure 4), the incumbent effect is far more pronounced in northern regions, but disappears in the Red belt, which indicates that the administrative experience acquired by mayors does not seem to impact on the personalization level of the vote. It appears that incumbent mayors in the North are more successful at capitalizing on the results of government actions, and can translate them into a consolidated personal consensus, while in the Centre and the South the results of administrative elections mainly strengthen the consensus for the lists and parties that selected and supported the mayor.

Figure 4. Personalization index of incumbent and not incumbent mayors by geopolitical area (N = 3649).

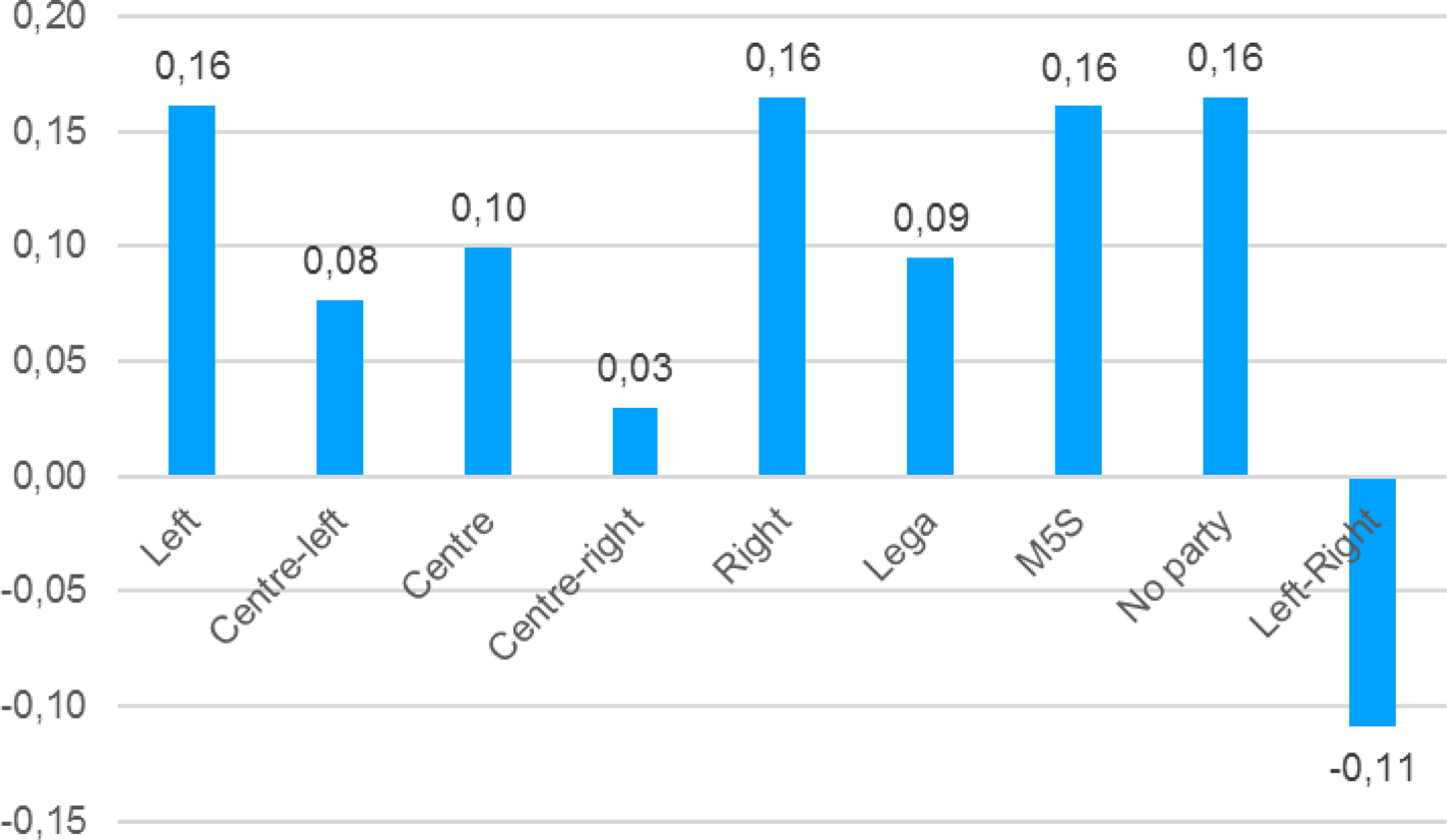

As regards the political aspects, one question we can answer, thanks to the information that we have gathered and processed, concerns the relationship between the political positioning of mayoral candidates and their appeal. In addition to the five traditional categories situated along the left-to-right spectrum, we decided to place the Lega Nord (Northern League) and the M5S in separate categories, due to the specificity of the Italian party system. While it is true that the Lega Nord has recently abandoned the reference to the North, added a specific reference to its leader in its symbol and name, and moved further towards extreme right-wing positions (Passarelli and Tuorto, Reference Passarelli and Tuorto2018), nevertheless the original Lega Nord adopted controversial political positions that it was not always possible to label strictly as either right-wing or centre-right (Mannheimer, Reference Mannheimer1993: 261; Biorcio, Reference Biorcio1999: 73). The political position of the Five-Stars Movement (M5S), which only made its debut in municipal elections in 2009, is equally controversial and not easily definable. In addition to the Lega Nord and the M5S, we have introduced an ‘other candidates’ category, which comprises candidates who are supported by civic lists, are an expression of civil society, or in any event are not directly supported by any recognized party. Finally, a small category (N = 41) consists of mayors supported by lists on both the left and right that for some ‘local’ reason have united behind the same candidate. As can be seen from Figure 5, the most personalized candidates are those located at the extremes of the traditional political axis, the M5S and the civic lists, all with an index value of 0.16. Being an outsider (or in any case a novelty) therefore pays better dividends in terms of the appeal of the mayoral candidates. If one looks at this phenomenon from the side of the lists however, it is possible to argue that the more moderate coalitions, which are also those that most frequently win electoral contestsFootnote 8 in a majority system with a two-round vote, are those that have the strongest council candidates, and which are able to mobilize a consensus that is not a consequence of their relationship with the mayoral candidate. On this point, the results of the analysis seem to agree with those obtained by Plescia (Reference Plescia2016: 103) in her study on the split ticket in the regional elections in Italy during the period between 1995 and 2010.

Figure 5. Personalization index by candidates' political colours (N = 19,219).

A final aspect considered in our analysis is the relationship between the number of lists supporting a candidate and the level of personalization (Figure 6). As can be seen, there is a very close – and equally clear – relationship between the two variables: personalization of the vote is higher in cases where the candidate is supported by one or two lists. From the third list onwards, attractiveness drops dramatically and in a linear fashion, and it falls to zero in the case of coalitions made up of seven lists; and from seven upwards, it even has a negative value. One possible interpretation of this clear relationship is that especially broad, fragmented electoral alliances cannot produce outsider mayoral candidates capable of motivating voters on their own. In this case, voters apparently vote more as a result of their closeness to the council candidate and/or the list rather than to the mayoral candidate. Mayoral candidates who are supported by multiple lists that are generally part of the main centre-left and centre-right coalitions, and which, as we have seen, are more likely to be successful, can more easily attract council candidates with roots in the local area, who therefore contribute significant individual preference votes. The strong personalization of votes for candidates who are supported by one, two, or even three lists may on the other hand be explained by the nature of these lists, which probably did not exist previously, but were created around the figure of the mayoral candidate, and therefore do not have their own well-established capacity to mobilize voters.Footnote 9

Figure 6. Personalization index by number of lists supporting the candidate (N = 19,219).

To conclude the analysis, we report the results of a linear regression which took account of the variables considered hitherto (see Table 1).Footnote 10 As can be seen, also considering the combined effect of the various variables, women are more personalized than men, while a university education is associated with higher levels of personalization. An interesting result concerns the outcome of the election: we noted above that the losers are on average more personalized than the winners. We have also seen that the losers were less personalized until 1999, whereas they were more personalized thereafter (see Figure 2). If we consider socio-demographic variables only (model 1), then the candidates elected are actually less personalized; but if we introduce the other variables in the model (models 2 and 3), then the winning candidates appear to be more personalized. This seems due in particular to the effect of the variable relating to the number of lists, which has a positive correlation of 0.484 with the variable relating to the outcome of the election. Indeed, the elected candidates are on average supported by a greater number of lists. At the same time, the support of a greater number of lists is associated with a lower degree of personalization of the candidate. As a result, the elected candidates are less personalized on average, but the number of supporting lists being equal, the elected candidates display greater personalization. Finally, the significant weight of the incumbent effect and the inverse relationship between the number of lists supporting the candidate and his or her personalization index is confirmed. Age does not seem to have any impact when considered ‘net’ of the other variables included in the model (model 2).

Table 1. Linear regression of the personalization index with respect to socio-demographic and political covariates

Conclusions

Twenty-five years after the introduction of the electoral law for municipalities, it is possible to make a fairly sound assessment of the results of its overall performance, as well as some of its more limited aspects. In this paper, by basing our analysis on an extensive, original dataset, we have explored the various aspects of the personalization of voting, and have drawn a distinction between votes for mayoral candidates and those for the lists associated with them. The picture that emerges makes it possible to clarify certain aspects of the personalization of politics, which has rapidly increased in Italy since the first half of the 1990s. Contrary to what might have been expected, candidates who are electorally stronger at a local level – like those who win compared with those who lose, and like men compared with women – are not the most attractive in terms of personalized votes. Winning candidates are therefore successful due not so much to their personal features as to the lists and council candidates associated with them. Accordingly, while it is true that personalization counts in municipal elections, given that it can trigger a significant number of votes, overall victory is still predominantly the result of the ability to create supporting lists.

From this standpoint, our analysis in this paper also makes it possible to articulate the various stages in Italy's political transition. The initial period (1993–1999), during which a higher level of personal appeal could be seen among elected candidates compared with those who were not elected, was followed by another period during which it was the losing candidates who were the most highly personalized. While, therefore, voters rewarded newness during the first stage, the new mayors became ‘old’, and therefore less appealing than their challengers, in the space of just a few years. This can be read as an expression of the constant need for novelty that results in support for individuals who put themselves forward as an alternative to established political actors in a strong, widespread climate of anti-politics at national and local levels. Among other things, votes for unsuccessful mayoral candidates are even more marked in the South, where the demand for novelty manifested itself in a very strong manner in the most recent national elections, with the dramatic success of the M5S.

Highly personalized mayoral candidates are therefore those who present themselves as outsiders. In addition to losing candidates and women (in particular female candidates in the South), this also applies to candidates on civic (or in any event non-party) lists and on those lists that take clearer ideological and programmatic positions; to candidates supported by one or two lists; and more recently to M5S candidates, who have made the rejection of political professionalism and anti-politics their leitmotif (Tronconi, Reference Tronconi2015). The greater personal attractiveness of outsiders therefore suggests that when voters are given more freedom of choice, which is guaranteed by an electoral system that provides for a split vote in this case, a significant number of voters will use it to vote for candidates who appear to be new, different and anti-establishment. A demand for something new therefore emerges where it is institutionally possible. It is never extinguished, but smoulders beneath the surface when electoral rules curb voters, as happened nationally in the case of the so-called ‘porcellum’, which provided for blocked lists and threshold barriers.

The anti-establishment movement that emerges from the results of our analysis is only mitigated by municipal political and electoral factors, which are tied to personal relationships between candidates (mayors and councillors) and voters. It is no coincidence that, with certain important exceptions (Parma, Livorno, Turin and Rome) where the election took on national significance, the performance of the M5S in the municipal elections was systematically worse than that in the national election. Nationally, on the other hand, the ‘plug’ caused by a ‘closed’ electoral system obliged anti-political movements to pursue other channels of expression. The increase in voter abstention and the success of the M5S in the 2018 national elections can be interpreted in this way. Similarly, in order to take advantage of the anti-political movement from a different position, established actors have had to turn to strategies that add value to the outsider dimension: the dismantling of the centre-left by a younger generation and the restyling of the Lega Nord, which has abandoned the word ‘Nord’ and wagered everything on its leader's ‘outsider’ style (tactical, demographic and perhaps also psychological) (King, Reference King2002).

The Italian political class will have to continue reckoning with the tendency of Italian voters to reward challengers, a trend that as we have seen in this paper affects not only the more programmatic and ideal national level, but also the pragmatic local vote. As has also been the case in other democratic contexts (Rosenbluth and Shapiro, Reference Rosenbluth and Shapiro2018), attempts to cure democracy with more democracy, as the main Italian parties (the PD with its primaries, the M5S with its promotion of direct democracy, and Salvini's Lega with the popularization of its leadership) have done, do not so far appear to have improved the relationship between citizens and the political class. If the 1993 municipal electoral reform has enjoyed widespread recognition over 25 years later, it may be due in part to the greater freedom – as measured by applying the criteria identified by Renwick and Pilet (Reference Renwick and Pilet2016: 21) – it gives voters. The political class might wish to take account of this aspect when tackling the persistent crisis of legitimacy that is a feature of the relationship between Italians and the nation's politics.

Data

The replication dataset is available at http://thedata.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/ipsr-risp.

Financial support

We are grateful for the financial support from the University of Bergamo, Department of Letters, Philosophy, Communication.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the review's two anonymous referees for their helpful comments, Vittorio Alvino and Ettore Di Cesare (Fondazione openpolis) for their help with the construction of the dataset, and Marco Betti, Lapo Filistrucchi, Dario Tuorto and Daniele Vignoli for their suggestions regarding the analysis conducted.

Appendix 1

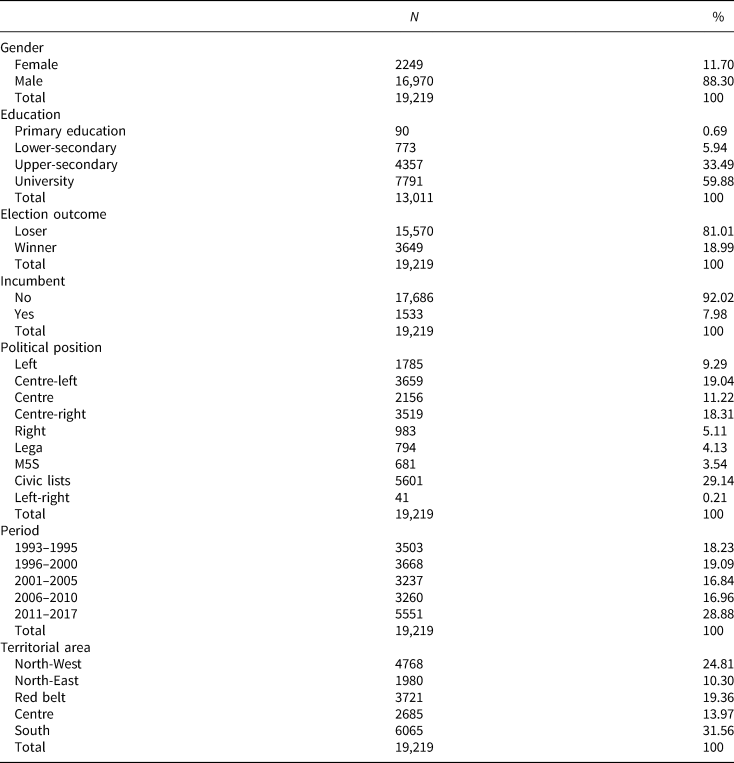

Table A1. Descriptive statistics for categorical variables in the regression models

Table A2. Descriptive statistics for continuous variables in the regression models